CHAPTER 21 Pain and Somatoform Disorders

Pain complaints are common in children and adolescents seen in primary and subspecialty care. These complaints represent a broad spectrum of conditions, including acute medical pain, recurrent or chronic pain, pain related to chronic disease, and pain in the context of a somatoform disorder. Pain that persists can have a profound effect on many areas of child and family life and can lead to problems with pain in adulthood. Affected children often challenge the diagnostic and therapeutic acumen of physicians and mental health professionals who care for them. The goal of this chapter is to review the most common acute and chronic pediatric pain problems, as well as somatoform disorders. We examine the diagnostic criteria, the prevalence, functional effect, causes, and empirically supported methods of assessment and treatment of pain conditions and somatoform disorders. The chapter closes with a discussion and summary of implications for clinical care, training, and research on pain and somatoform disorders in children and adolescents.

DEFINITIONS OF PAIN AND SOMATOFORM DISORDERS

Some basic definitions are presented here to orient the reader to the problems of pediatric pain and somatoform disorders covered in this chapter. Pain is defined by the International Association for the Study of Pain as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage.”1 Pain has a sensory and affective component. Neuroimaging studies2,3 have demonstrated the differential pain perception areas of the cortex that are involved in affective pain perception and those involved in sensory pain perception. Pain can be categorized as acute or chronic, although there is no definite criteria of how long pain must persist to become “chronic,” other than an agreed-upon operational one (e.g., 3 months).

Acute Pain

Acute pain is usually a signal that there is some tissue injury, inflammation, or infection that may necessitate immediate attention. For example, a fall from a bicycle may produce a scraped and bruised knee. The knee is experienced as acutely painful because there is tissue injury, which activates local afferent nerve fibers through the local release of neural activators, such as prostanoids, substance P, and other local neurotransmitters. In turn, afferent nociceptive fibers provide messages to connector neurons in the spinal cord, with the release of other local neurotransmitters, and the ascending transmission of nociception up to pain perception areas in the brain is initiated. In acute pain, typically the descending neural inhibitory system is rapidly activated; then the pain process becomes diminished, and soon the pain goes away. Motor reflexes may also be activated, such as withdrawing a finger from a hot plate if the finger’s sensation is experienced as too hot and painful. Phylogenetically, acute pain is protective and serves as a warning signal to take action. Acute pain is typically brief and usually ends shortly after the acute injury occurs; after it heals; after the inflammation has subsided; or when the stretch, contraction, or impingement on the body part has resolved. Examples include a broken arm, postsurgery pain, acute gastroenteritis, menstrual cramps, a sore throat, pain from an ear infection, or acute muscle cramps related to significant exercise. This type of pain can be mild to severe, but most acute pain conditions are readily diagnosable, which means that the source is fairly easily discovered. Although the source may be known (e.g., surgery), physical movement, emotions, beliefs, and environmental factors (e.g., what physicians, nurses, and parents do and say) can affect both the severity and duration of the pain, complicating the assessment and management of acute pain.

Somatoform Disorders

Somatoform disorders are a group of psychiatric disorders described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), 4th edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR)4 as the presence of physical symptoms suggestive of an underlying medical condition but for which the medical condition is neither found nor fully accounts for the level of functional impairment. In medicine, these conditions are classified as functional somatic syndromes.5 DSM-IV-TR somatoform disorders include somatization disorder, conversion disorder, pain disorder, undifferentiated somatoform disorder, hypochondriasis, and body dysmorphic disorder. Except for body dysmorphic disorder, characterized by a preoccupation with an imagined or exaggerated defect in physical appearance, all the other somatoform disorders frequently have pain as part of the presenting complaint. Thus, the other somatoform disorders are included in this chapter, with the recognition of the limited research base in children and adolescents. However, because there may be precursors of adult somatoform disorders identifiable in children, we believe it is important to be inclusive of them in our review.

CLINICAL AND SCIENTIFIC SIGNIFICANCE OF PAIN AND SOMATOFORM DISORDERS

Prevalence of Pain and Somatoform Disorders

Pain among children and adolescents has been identified as an important public health problem. Acute pain is commonly encountered in hospitalized pediatric patients.6 Chronic and recurrent pain is also commonly experienced. According to epidemiological study estimates, chronic and recurrent pain affects 15% to 25% of children and adolescents.7,8 One population-based study revealed a pain prevalence of 54% in a large sample of youths aged 0 to 18 years; 25% of the respondents reported chronic pain lasting more than 3 months, and more than 25% of respondents reported a combination of multiple locations of pain.8 The most commonly reported pain sites in epidemiological studies are the head, abdomen, and limbs.7,8

The prevalence of specific pain conditions has also been explored. Depending on the definitions of recurrent abdominal pain that are used, prevalence estimates range from 10% to 19% of children and adolescents.9 Migraine is estimated to occur in 10% to 28% of children and adolescents.10,11 Episodic tension-type headache has been estimated at a prevalence rate of 12.2% among school-aged children.12 The prevalence of pediatric headache has apparently increased since the early 1980s. Musculoskeletal pain complaints have been reported as common in the general pediatric population; available prevalence estimates are 29% for back pain, 21% for neck pain, and 7.5% for widespread pain. Estimates of fibromyalgia syndrome in the general American adult population are 2%,13 but specific estimates for the juvenile form are not available.

Pain also occurs in the context of chronic health conditions such as sickle cell disease, arthritis, and cancer. Recurrent and disabling pain symptoms have been reported to affect as many as 15% of patients with sickle cell disease.14 On average, children with sickle cell disease experience pain episodes five to seven times per year and require hospitalization one or two times per year for pain.15 For young and school-aged children, the majority of pain episodes occurs at home and are managed primarily by families.15,16 Studies have shown that mild to moderate intensity pain is quite common in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis17 and occurs on a weekly basis for many such children. Epidemiological studies demonstrate that children with cancer experience frequent pain; an estimated 54% to 85% of pediatric hospitalized cancer patients report pain, and 26% to 35% of children in the outpatient setting report cancer-related pain.18–20 Children with cancer may experience pain at the time of cancer diagnosis, during active treatment, and at the end of life.

Prevalence of Somatoform Disorders

Although there is little available information regarding the incidence and prevalence of specific somatoform disorders in the pediatric population, medically unexplained somatic symptoms, particularly pain, are common. The prevalence rates of recurrent somatic symptoms among children and adolescents generally range from 10% to 20%, the most common symptoms being recurrent head pain and abdominal pain.7,8 Less common complaints include symptoms such as back and chest pain, low energy, fatigue, extremity numbness/tingling, and other gastrointestinal complaints.21

Somatoform disorders are common in adults seen in primary care; prevalence estimates are 10% to 15%.22,23 Little information concerning the prevalence of specific somatoform disorders in children and adolescents is available. In an early survey conducted in pediatric primary care, the prevalence rate of psychosomatic diagnoses in children ranged between 5.7% and 10.8%.24 However, in a community sample of 540 school-aged children, Garber and colleagues25 found that only 1.1% of children met full diagnostic criteria for somatization disorder according to criteria of the third edition, revised, of the DSM (DSM-III-R). There are multiple published case reports and case series documenting conversion disorder in children and adolescents, for example,26 but no incidence data are available. Similarly, no incidence data for hypochondriasis, pain disorder, or undifferentiated somatoform disorder in children or adolescents are available. In general, diagnosed somatoform disorders are rarely documented in pediatric samples, probably because the diagnostic criteria were established for adults and it is controversial whether they are applicable to children. However, at present, an alternative, developmentally appropriate classification system is unavailable. In view of the profound effect of unexplained medical symptoms on children and adolescents, increasing the relevance of the diagnostic criteria for children will be a major advance in the classification system.

Consequences of Pediatric Pain and Somatoform Disorders

The functional consequences of pain and somatoform disorders on children and adolescents can be significant. In general, somatic symptoms are associated with increased risk for psychopathology, family conflict, parent-perceived ill health, school problems and absenteeism, and excessive use of health and mental health services.27 Specifically, although many children with pain conditions cope very well, other children experiencing pain develop psychosocial difficulties, academic problems, disruptions in peer and family relationships, and anxiety and depression. Chronic pain, in particular, can have a major effect on the daily lives of children and adolescents. According to clinical descriptions of extreme chronic pain and disability in children,28 some children who experience chronic pain develop significant impairments in their academic, social, and psychological functioning. These children frequently miss considerable amounts of school, may not participate in athletic and social activities, and may suffer anxiety or depression in response to uncontrolled pain.

There exists a continuum of functional consequences of pain on children and adolescents: At one end of the spectrum is the experience of pain symptoms but minimal day-to-day impairments; at the other end is the experience of pain symptoms accompanied by profound effects on most aspects of daily functioning and severely reduced quality of life. Health-related quality of life is a multidimensional construct that refers to an individual’s perception of the effect of an illness, symptoms, and its consequent treatment on the person’s physical, psychological, and social well-being.29 Several examinations of health-related quality of life have been undertaken in children with chronic pain. Unexplained chronic pain in adolescents has been associated with poor quality of life in the adolescent, as well as in the family.30 Children and adolescents with headaches suffer reductions in health-related quality of life in comparison with same-age peers without head pain.31 Frequent pain in the context of chronic disease also impairs quality of life. Youth with sickle cell disease32 and youth with cystic fibrosis33 have been found to experience specific reductions in physical, psychological, and social functioning in relation to the experience of frequent pain.

Disability that results from chronic pain is a concept separate from pain itself and equally important to consider in assessment and management of pediatric pain patients.34 Disability refers to the areas in an individual’s life that are limited because of pain (i.e., the things that a person cannot do because of pain). For children, disability can be demonstrated in the home and school setting.34,35 The domains of functioning that seem to be particularly affected by chronic pain and that are reviewed in the following sections include school and academics, participation in physical and social activities, sleep disturbance, and family disruption.

SCHOOL FUNCTIONING

In industrialized cultures, a child’s sole responsibility is to attend school. Children with pain conditions often have difficulties accomplishing this important task. For example, children experiencing pain related to sickle cell disease,16,36 widespread musculoskeletal pain,37 and recurrent abdominal pain38 have been found to have higher rates of school absenteeism than do controls. The number of missed school days is quite substantial. In one study, patients with sickle cell disease were absent from school on 21% of school days, or about 6 weeks.16 Similarly, in a study of children with CRPS, affected children on average missed 40 school days.39 Migraine headaches, which affect approximately 1 million children and adolescents, have been reported to lead to school absence rates of several hundred thousand missed days per month.40 A high rate of absenteeism can have direct effects on academic performance and school success, as well as important effects on socialization and maintenance of peer relationships. Many children and adolescents with chronic pain experience extreme stress because of missing school and the subsequent difficulty in making up and keeping up with classwork. This can lead to a vicious cycle of missed school and increased stress that further compromises their ability to cope with the pain problem.

PHYSICAL AND SOCIAL ACTIVITIES

As with the effect on school attendance, recurrent and chronic pain affects children’s participation in developmentally appropriate physical and social activities. Adolescents with headaches41 and children with sickle cell disease36 have reported a significant effect of pain on the amount of leisure time with peers in comparison with healthy controls. The majority of children with unexplained chronic pain suffer impairment in sports activities and social functioning.42 Specific activities that are most often reported by children themselves as difficult to perform because of chronic pain are sports, running, gym class, schoolwork, going to school, and playing with friends.43 In particular, when pediatric patients become severely disabled by chronic pain, their lives may become very isolated and restricted with few opportunities for enjoyment of friends and normative activities.

EMOTIONAL FUNCTIONING

Persistent pain can also have a substantial effect on the emotional status of children and adolescents. In general, children with recurrent pain experience more stress, feel less cheerful, and feel more depressed than do children without pain.44 Higher levels of depressive symptoms are associated with higher levels of pain both in children with a chronic disease45 and in children with chronic nonmalignant pain.46 Moreover, increased depressive symptoms are associated with increased functional disability that children experience in relation to chronic pain.46

There have been only a few investigations to specifically report on the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents with chronic pain. Chronic pain does appear to be associated with psychiatric comorbidity, particularly anxiety and mood disorders. For example, in a sample of children seen in a primary care setting for recurrent abdominal pain, 79% of children met criteria for an anxiety disorder and 43% for a depressive disorder.47 Further studies are needed to disentangle the temporal sequence of chronic pain and psychiatric disturbance. It is currently not clear whether psychiatric disturbance typically predates the pain problem or whether the psychiatric disturbance develops in reaction to living with unremitting or disabling pain.

SLEEP DISTURBANCE

Pain can also interfere with the quality and quantity of children’s sleep, and sleep deprivation, in turn, can reduce children’s ability to cope with pain and enhance pain sensitivity. More than half of children and adolescents with chronic pain report sleep difficulties.7 Disturbed sleep has been identified in a number of specific chronic pain syndromes in children and adolescents, including juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, headache, CRPS, sickle cell disease, fibromyalgia, and recurrent abdominal pain. Researchers have begun to describe these sleep disturbances, finding that these children and adolescents experience difficulty falling asleep, frequent night and early morning awakening, and excessive daytime sleepiness. Inadequate sleep quantity and quality are linked to significant problems in several aspects of daily life for children and adolescents.48 Daytime sleepiness resulting from both suboptimal sleep duration and sleep disturbance is associated with reduced academic performance, attentional difficulties, mood disturbance, and increased school absences.48,49 For children and adolescents with chronic pain who may already be experiencing functional limitations in their daily lives, good quality sleep may be even more crucial than for their pain-free peers. The disruption in sleep in some children and adolescents may be a marker for problems with functional disability or may signal the progression into chronic pain syndromes. (Lewin and Dahl50 reviewed the importance of sleep in the management of pediatric pain, highlighting the bidirectional effects between sleep and pain.) In adolescents with chronic pain, impaired sleep has been shown to reduce functioning in a broad range of physical and social activities and health-related quality of life.51

FAMILY AND SOCIETAL CONSEQUENCES

Childhood chronic pain is known to have negative effects on family life, including increased restrictions on parental social life and higher parental stress levels, in comparison with families whose children do not have chronic pain.30,52 Parents are most often responsible for initiating a child’s contact into the health care system and ultimately carry the burden of daily care for these children. In one study, parents’ perception of more illness-related stress was the strongest predictor of health care use in children with sickle cell disease.53

Apart from the individual and family effects of chronic pain, there is also a potential societal effect of chronic pain that can be demonstrated in increased health care utilization and possible subsequent economic costs, whereby pain-related functional impairment prevents work.34 The economic costs of adult chronic pain are well documented in terms of lost work productivity and costs of prescription pain medications.54 The economic costs of childhood chronic pain have not yet been fully described. However, direct costs of pain treatment include medical costs such as hospitalization, doctor’s visits, and medications. Indirect costs include parental time off work, transportation costs, child care, and incidental expenses. Children and adolescents with chronic pain may account for a disproportionate number of contacts with the health care system, contributing to millions of dollars spent annually on health care costs for chronic pain.55 Prior studies have demonstrated that individuals living with chronic pain have increased usage of the health care system for routine medical visits, hospital overnight stays, and emergency room visits.56,57 For example, in a population-based sample of 5424 children and adolescents, 25% reported chronic pain, and of these, 57% had consulted a physician for pain. In a similar epidemiological study, 53% of children and adolescents had used medication for pain, and 31% had consulted a general practitioner.58

RESEARCH ISSUES AND CONTROVERSIES

Pain and somatoform disorders can have a broad effect on children’s daily functioning and well-being. As such, studies of children with pain conditions should include relevant outcome variables, including measures of pain and distress, function, quality of life, health care utilization, and economic factors. Although some progress has been made in describing specific areas of functioning that are affected by pain, very little is known about the effect of pain in other areas. For example, although adult chronic pain has been identified as among the most costly medical conditions in industrialized societies,59 economic outcomes are only beginning to be measured in the pediatric population. In one study conducted in the United Kingdom,60 a cost-of-illness analysis was completed with adolescents who received treatment for chronic pain; the mean cost was found to be £8027 per child per year, which is equivalent to approximately $14,000 in the United States, including direct service use costs, out-of-pocket expenses, and indirect costs (e.g., lost employment). The longer term costs of pediatric chronic pain are unknown because there are currently no data to indicate whether effective treatment results in reduced costs related to pain in adulthood. More longitudinal data on the outcome of adolescents with chronic pain are needed in order to estimate the true lifetime costs of pain.

CAUSES

Acute pain typically has a clear source and cause. In contrast, chronic pain often occurs without a clear cause. Somatoform disorders are assumed to result from psychological processes; however, the specific mechanisms by which this occurs are largely unknown. Various theories of acute and chronic pain in children have been presented over the years. Many of these theories focus on factors that explain the chronicity and impairment experienced from pain because there is no one-to-one correspondence between the severity of pain and the amount of disability or impairment. Some children may experience relatively severe pain but show surprisingly little impairment, whereas others with milder pain can have more problems in their day-to-day functioning. There may be different causes of pain and disability. For example, a child’s pain may result from inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), but the child may not participate in school or recreational activities because the parent is overprotective and has reinforced a sick role. Illness and symptom-related factors are only one source of the variance in functional outcomes.61

Because considerable interindividual variability has been observed with regard to children’s pain perception and extent of limitations in daily functioning, children’s pain is understood in current models within a biopsychosocial framework. A number of models, including the biopsychosocial model of pain,62 the fear and harm avoidance model,63 and the self-efficacy model,64 have this framework. Central to these models are interrelationships among physical, cognitive, affective, and social factors that influence pain and disability outcomes. The following sections summarize several etiological factors that arise from the biopsychosocial model, including developmental factors, sex, family factors, and physiological mechanisms. Although these models tend to include both pain and disability as outcomes with similar sets of contributing factors, we have divided the section below into two parts: (1) etiological factors that seem to play a larger role in the incidence of pain and somatoform disorders and (2) etiological factors that seem to determine the extent of children’s pain-related disability.

Etiological Factors in the Incidence of Pain and Somatoform Disorders

In current conceptualizations of pain and somatoform disorders in children, the importance of age, sex, psychosocial stressors, and central nervous system mechanisms for understanding the etiology of pain problems is recognized. For example, the incidence of pain problems follows a clear developmental sequence. Headache increases dramatically with age. Before puberty, recurrent headache occurs at a low rate, and there is a slightly greater incidence of headache in boys.65–68 With the onset of puberty, the incidence of both migraine and tension-type headaches increases dramatically, and the incidence of headache in girls is much higher, as is documented in adult studies.67 Puberty plays an uncertain role in the development of chronic pain in children and youth.

In the pediatric population, somatoform disorders tend to follow with a developmental sequence, whereby younger children frequently present with a single somatic complaint, often as a consequence of affective stress, most frequently manifesting as abdominal pain and headaches. Teenagers are more likely to present with multiple complaints, and symptoms such as fatigue, extremity pain, aching muscles, and neurological symptoms increase with age.69

Sex differences have emerged in children’s symptom reporting and development of endogenous pain and somatic complaints. In nonreferred samples, girls generally report higher pain intensity, longer lasting pain, and more frequent pain than do boys.8 There is an increased prevalence of several pain problems in girls in comparison with boys, especially after puberty. For example, girls are more likely to be treated for CRPS, fibromyalgia, and migraine headaches. There appears to be a 2:1 ratio of girls to boys presenting with somatoform disorders across all age ranges.

Psychosocial stressors—including a parent with a physical illness, depression, anxiety, or somatization disorders; high levels of parental distress; and a history of physical or sexual abuse—are seen significantly more frequently in children in whom somatoform disorders are diagnosed.69,70

There are also various central nervous system pain mechanisms that may play a role in the persistence of pain. The neurophysiology of pain is an area of active research.71,72 For example, in understanding functional bowel disorders, current theories suggest that the pain or symptoms are caused by abnormal brain-intestinal neural signaling that create intestinal or visceral hypersensitivity. Abdominal pain is thought to be brought on by visceral hyperalgesia, which may be caused by alterations in the sensory receptors of the gastrointestinal tract, abnormal modulation of sensory transmissions in the peripheral or central nervous system, or changes in the cortical perception of afferent signals.73

Etiological Factors in Pain-Related Disability

In considering etiological factors in children’s pain-related disability, various factors have been conceptualized to play a role, including children’s coping, anxiety and depressive symptoms, and family reinforcement of pain behavior.34 Identification of factors that are predictive of disability related to pain is an active area of pediatric pain research,74,75 particularly because many of these factors represent areas that can be directly targeted in behavioral interventions.

Investigations of children’s coping responses to pain have revealed that certain coping strategies relate to better functional outcomes. Specifically, children who use more approach coping (i.e., direct attempts to deal with pain and the use of active methods to regulate feelings when in pain) report less pain-related disability.61,74 Coping skills have been targeted in treatment studies to test the hypothesis that increasing children’s use of adaptive coping responses would, in turn, decrease pain-related disability.76,77

Psychological distress, particularly anxiety and depressive symptoms, can be viewed as an outcome of a pain condition or as an etiological factor in the development of pain-related disability. Studies have demonstrated that increased depressive symptoms are associated with increased functional disability related to chronic pain.46 Palermo34 emphasized the importance of considering the relationship between emotional distress and children’s functional status because emotional distress may affect many areas of functioning such as reduced participation in peer activities and sleep disturbances. For example, depressive symptoms were found to be predictive of reductions in health-related quality of life as a result of sleep disturbance in adolescents with chronic pain.51 To date, there have been no investigations to specifically tease out the effects of psychological distress on specific aspects of children’s pain-related disability.

A variety of familial factors have been identified as potentially important in the causes of pain-related disability, including parental responses to the child’s pain, parental psychopathology, and parental history and modeling of chronic pain symptoms. A number of researchers have noted a family aggregation of pain complaints, finding that children with chronic pain often live in households in which other family members also have chronic pain.78 Although preliminary twin studies indicate that there may be a genetic link, it is commonly thought that somatization is a learned behavior. Through the process of modeling, children may learn about pain perception and reaction to pain from others. Of importance is that in the context of chronic pain, parental modeling of avoidance behavior and poor coping skills may be particularly problematic, because they are at direct odds with the adaptive child behaviors that are needed to cope effectively with chronic pain.

Parental encouragement or reinforcement, sometimes referred to as solicitous responses (e.g., frequent attention to pain symptoms, granting permission to avoid regular activities), has been investigated in children with chronic pain.79 The effect of parental responses on children’s pain is presumed to occur because a parental solicitous response may be a reinforcing consequence of a pain behavior, thus serving to maintain or increase the likelihood that the behavior will occur. There is evidence that more solicitous or encouraging responses from parents toward their children’s pain or illness behaviors do increase sick role behaviors in children with recurrent and chronic pain. Parental solicitous responses have been reported to be particularly problematic for children presenting with increased anxiety or depressive symptoms, who were the most disabled by pain when their parent demonstrated this response style.80

Natural History and Course of Pain

Investigators have examined whether early and prolonged exposure to pain alters later stress response, pain systems, and behavior and learning in childhood. There is some evidence that children who undergo pain or tissue damage as neonates may have increased pain sensitivity later in childhood.81 This has important implications for the long-term care of these patients, because they may be more likely to develop problems with chronic pain in later life.

In short-term follow-up studies of children with chronic pain, a significant number of children are found to have continuing complaints of pain over 1- to 2-year follow-up periods. For example, in one study, children with recurrent benign pain were monitored over 2 years; 30% of the initial sample had continuing pain at the 2-year follow-up.82 The children whose pain persisted over time were reported to have more emotional problems than did children without persisting pain complaints, and their mothers had poorer health than did the controls’ mothers. Other studies have identified depressive symptoms as important in predicting generalization of pain from one localized site (i.e., neck pain) to widespread pain at the short-term follow-up.83

Long-term outcome studies suggest that children and adolescents who present with chronic abdominal or headache pain continue into adulthood with chronic pain, physical, and psychiatric complaints.84–86 There is evidence that childhood history of recurrent abdominal pain may predispose children to irritable bowel syndrome in adulthood.87 Children whose chronic pain limits their functioning may develop lifelong problems with pain and disability. It is unknown whether medical and psychological treatments alter these long-term outcomes for children with chronic pain.

RESEARCH ISSUES AND CONTROVERSIES

Potential areas of research focus within the causes and natural history of childhood pain may involve sociocultural studies, the developmental psychology of pediatric pain, and the relationship between pediatric and adult chronic pain. The available data on the etiology and natural history of childhood pain and somatoform disorders are insufficient to lead to effective prevention efforts. Longitudinal studies are needed to identify the course of pain and pain-related disability in different populations of children. Furthermore, longitudinal studies are needed to document the development of pain and somatoform disorders in at-risk groups. For example, retrospective studies have revealed an increased incidence of pain and physical comorbidity in girls with posttraumatic stress disorder,88 but there have been no investigations to monitor children with this disorder over time to identify factors predictive of the development of pain conditions.

DIAGNOSIS/ASSESSMENT

Acute Pain

Acute, or nociceptive, pain arises from tissue inflammation or injury caused by a noxious event.89 Examples of these processes include a broken arm, postsurgery pain, acute gastroenteritis, menstrual cramps, a sore throat, pain from an ear infection, or acute muscle cramps related to significant exercise. This type of pain can be mild to severe. Besides acute injuries and acute infections, the two most common types of acute pain include postoperative pain and medical procedure–induced pain. The majority of studies of medical procedure–induced pain have focused on pain related to intravenous insertions and phlebotomies90–92 and to bone marrow aspirations and lumbar punctures in children with cancer.93,94

The child’s experience of acute pain depends on relevant situational factors (e.g., understanding, predictability, and control) and emotional factors (e.g., fear, anger, and frustration), which are influenced by a child’s sex, age, cognitive level, previous pain experience, learning, and culture.89 Distress and anxiety are important factors to consider in acute pain because they can intensify the child’s experience of pain and prolong recovery. Assessment of both pain and anxiety for postsurgical and medical procedure–related pain has received considerable research attention and, as detailed later in this chapter, there are many different tools and methods of measuring pain, including various self-report measures, observational measures of specific behaviors, and measures based on physiological monitoring.

Pain Related to Chronic Disease

SICKLE CELL DISEASE

Sickle cell disease is a genetic hematological disorder that affects the hemoglobin in red blood cells, causing the hemoglobin to form crystalloids that become less elastic than normal hemoglobin, resulting in long, misshapen red blood cells that have a “sickled” appearance. These abnormally shaped cells tend to aggregate rather than flow through blood vessels singly. This aggregation of red blood cells causes blockage in arteries, resulting in vaso-occlusive pain crises. Children with sickle cell disease are also vulnerable to infections (especially those caused by Pneumococcus organisms), organ damage related to episodes of ischemia, and, in some cases, early death.95 Sickle cell disease is most prevalent among African-Americans and Hispanic-Americans; approximately 1 of every 500 African-American children and 1 of every 1400 Hispanic-American children are born with sickle cell disease.96

Ischemia causes pain through a buildup of certain nociceptive neurotransmitters, such as substance P and prostanoids, at afferent neural endings, and the ascending pain signal system is thus activated. Ischemic pain has been described by one of our clinic patients as “feeling like your arm is being squeezed by a blood pressure cuff that keeps getting tighter and tighter until your arm begins to ache and the pain may become unbearable.” Pain may originate from many sources (e.g., musculoskeletal, visceral), and affected children may experience both acute and chronic pain (e.g., aseptic necrosis, bony infarction). For example, in children and adolescents with sickle cell disease, headaches97 and low back pain can result from chronic muscle spasm and lack of oxygen in the spine; joint pain, especially in the hip, can result from aseptic necrosis of the femoral head; hip arthritis often causes a deep, aching “referred” pain in the lower thigh above the knee; and acute chest syndrome, with accompanying severe chest pain and shortness of breath, can develop, as can ischemia, which can affect almost any organ, causing visceral pain.

Children with sickle cell disease are also at risk for neurological sequelae and neuropsychological impairment.98 It is estimated that 7% to 17% of children with sickle cell disease experience a clinical stroke before age 20,99 and 10% to 20% of children may exhibit evidence of silent strokes, with associated cognitive deficits.100 Learning impairment can increase school-related stress. Children with sickle cell disease often have short stature related to spinal infarcts and collapsed or narrowed vertebrae or renal disease; the short stature may add to social stress. In turn, stress can further exacerbate any pain.

Some children with sickle cell disease have frequent, repetitive bouts of pain, whereas others have a milder, intermittent form. The contributors to this variance may be related to aspects of the disease or to characteristics of the child and his or her environment.

INFLAMMATORY BOWEL DISEASE

IBD is a condition of ongoing or recurrent inflammation in the intestinal tract.101 IBD is not to be confused with irritable bowel syndrome, which is a functional gastrointestinal disorder characterized by abdominal pain and altered bowel habits in the absence of specific and unique organic disease. There are several forms of IBD. The two most common are Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.102 Crohn’s disease is a condition that can affect the entire intestinal tract with patchy inflammation that can involve all the layers of the wall of the intestine. The early signs of Crohn’s disease in children are often vague, making diagnosis difficult. Periumbilical pain or right-sided abdominal pain are the most common sites of pain and may appear long before significant diarrhea. Children with Crohn’s disease may also have joint pain and fever before there are any changes in bowel patterns. Decreased appetite and weight loss are often symptoms misdiagnosed as anorexia nervosa, school anxiety, or other psychological problems.

JUVENILE ARTHRITIS

Arthritis is an autoimmune disease, and juvenile arthritis is medically different from the adult form of rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis. Juvenile arthritis can cause joint deformities and affect a child’s skin, eyes, and visceral organs. More than 250,000 children in the United States have some form of arthritis.103 It can start as early as infancy and lasts a lifetime. Arthritis is an inflammation in the joints that causes afferent neurons to transmit nociception to the spinal cord and to pain perception areas in the brain, resulting in joint pain. Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis is an autoimmune condition involving primarily pain and inflammation in the joints.103 Sometimes involvement extends to only a single joint (monoarticular arthritis), sometimes to a few joints (pauciarticular arthritis), and sometimes to many joints (polyarticular arthritis). In some cases, other parts of the body are involved, such as the eyes, in which there may be inflammation of the uvea. There are other, less common causes of arthritis, besides juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, such as arthritis associated with IBD, infections of the joints, and other autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus. In contrast to affected adults, 30% to 50% of affected children go into remission after several years, depending on the arthritis subtype.103

CANCER

Medical-procedure pain is the most common acute pain associated with childhood cancer.20 Common procedures include bone marrow aspiration and biopsy, lumbar puncture with or without the administration of intrathecal medication, intravenous insertion for chemotherapy administration (although most chemotherapy is now given through a central access catheter), and phlebotomy. Children who have vincristine chemotherapy may develop neuropathic pain associated with a peripheral neuropathy. Bone marrow transplantation is typically associated with a 7- to 10-day period of mucositis, with painful mouth, swallowing, urination, and defecation and pain in any areas involving mucosal surfaces (e.g., diarrhea associated with mucosal sloughing). Graft-versus-host disease may occur in some children after transplantation and can affect any organ, including skin. When solid tumors are increasing in size or if there is an acute hemorrhage within a tumor, the tumor can compress nearby or surrounding tissue, causing compression pain, capsular stretching pain, or hollow organ obstruction. Survivors of certain types of malignancies, such as bone tumors, other sarcomas, and Hodgkin disease, may continue to have pain long after treatment termination.

Headaches

Headache is a symptom that is almost universally experienced. Usually, headaches are considered a problem when they are severe, arise frequently, and start impeding sleep, eating, activities, or school performance. Headaches occur for a variety of reasons. Sometimes allergies or changes in barometric pressure can cause headaches in relation to fluid shifts in the sinus cavities. Caffeine, monosodium glutamate, and tannins in foods, as well as allergies to certain foods, also can trigger headaches. Other types of headaches include those occurring after head injury, those related to sensory “overload” (e.g., often in children with sensory integration problems, autism spectrum disorder, or Asperger syndrome), myofascial or tension headaches (often called “chronic daily headaches”), temporomandibular joint headaches (often called “facial pain” headaches), vision-related headaches, and migraine. It is not uncommon for children with occasional migraine headaches to develop chronic daily myofascial headaches. In a review of pediatric cases presenting to an emergency department with headache as the primary complaint, children’s diagnoses included viral illness (39.2%), sinusitis (16%), migraine (15.6%), posttraumatic headache (6.6%), streptococcal pharyngitis (4.9%), and tension headache (4.5%).104

The International Headache Society classifies adulthood and childhood headaches as primary headaches (e.g., migraine and tension-type headaches), secondary headaches (e.g., headache attributed to infection or trauma), cranial neuralgias, facial pain, and other headaches. Pain in the head is a primary component of the diagnosis of primary headache disorders, although other symptoms such as nausea and vomiting may also accompany head pain. The reader is referred to the second edition of the International Classification of Headache Disorders105 for a complete listing of the diagnostic criteria and classification of children’s headaches.

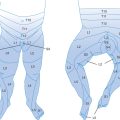

Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS)

CRPS (formerly known as reflex sympathetic dystrophy) consists of a focal painful disorder in any part of the body, often one or both of the extremities.106 Pain may occur after a minor injury or surgery but also may occur without an obvious prior event. The diagnostic criteria of this type of pain include severe pain; skin hypersensitivity, including allodynia (pain to light touch); and vasomotor instability. The first reported case of CRPS in children appeared in the literature in the 1970s, approximately 100 years after the first described adult case. The pain is often described as a burning, squeezing, or stabbing/shooting pain. The hallmark of CRPS is that the affected area is supersensitive to even light touch, has the type of pain just described, and often interferes with the use of the affected part (e.g., leg or arm). Sometimes there are swelling and color, skin, and hair changes from lack of touch to that body part, and there may be muscle atrophy and weakness from nonuse. There are many theories that exist to explain the pathophysiology of this syndrome; however, none fully explains the expression of this condition.

Juvenile Fibromyalgia

Fibromyalgia is a disease characterized by chronic widespread pain in the fibrous tissues of the muscles, ligaments, and tendons and often includes fatigue.107 In children and adolescents, it is not well understood and often misdiagnosed. Many physicians continue to call this a “psychosomatic disease” and believe that it is psychological and not “real.” In affected children, fibromyalgia is often mistakenly diagnosed as growing pains or psychological problems. Little is still known about juvenile fibromyalgia, even though research in adult fibromyalgia is increasing. In this condition, most rheumatological blood tests typically yield negative results, or the antinuclear antibody count may be mildly elevated. The diagnosis is based on a history of widespread pain and numerous tender points throughout the body.108

Functional Bowel Disorders

Functional bowel disorders are identified by abdominal pain with or without other gastrointestinal symptoms and are not associated with inflammatory, metabolic, or structural abnormality of the intestinal tract.73,109 Recurrent abdominal pain was originally defined by Apley and Naish110 as the child’s experience of three episodes of abdominal pain within a 3-month period that affected his or her activities. Functional bowel disorders are currently classified according to the Rome criteria,111 in which five types of functional gastrointestinal conditions associated with abdominal pain are characterized: functional abdominal pain (diffuse abdominal pain without any other gastrointestinal symptoms), functional dyspepsia (ulcer-like pain in one spot at the base of the sternum), irritable bowel syndrome (widespread abdominal pain with other gastrointestinal symptoms, such as nausea, vomiting, bloating, constipation, and/or diarrhea), abdominal migraines (which are rare), and aerophagia (abdominal distention due to intraluminal air). The pain or symptoms are caused by abnormal brain-intestinal neural signaling that create intestinal hypersensitivity and may thus result in increased pain. The pain relates to hypersensitivity rather than to intestinal contractility, although both may be linked. As mentioned, abdominal pain may be caused by alterations in the sensory receptors of the gastrointestinal tract, abnormal modulation of sensory transmissions in the peripheral or central nervous system, or changes in the cortical perception of afferent signals,73 which may have been preceded by inflammation that has since resolved.

Description of Somatoform Disorders

In the DSM-IV-TR,4 Somatoform Disorders is defined as a broad diagnostic category to which a number of more specific diagnoses belong. Although the DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria were designed for adult patients, at present they are also applied to the pediatric population, because, to date, no more age-specific, widely accepted, generalized classification system has been developed. Several of the disorders have a number of features in common with Axis II personality disorders involving character traits. Because character traits are viewed as evolving in childhood rather than firmly established, there is a reluctance to diagnose personality disorders in child psychiatric patients that also applies frequently to somatoform disorders.69 Moreover, there has been much criticism in the psychiatry community in regard to this diagnostic category, and suggestions have been made for modification during the planning period for the fifth edition of the DSM (DSM-V).112 Several specific criticisms of the somatoform disorder category include the unacceptability of the terminology to patients, the dualism splitting disease versus psychogenic causes, and incompatibility with other cultures. As outlined in the DSM-IV-TR, the broad category of somatoform disorders includes conversion disorder, pain disorder, body dysmorphic disorder, hypochondriasis, somatization disorder, and undifferentiated somatoform disorder. We describe each of these disorders briefly as follows, except for body dysmorphic disorder, which does not involve pain complaints.

SOMATIZATION DISORDER

Somatization disorder is a chronic condition consisting of multiple medically unexplained bodily complaints for which treatment has been sought over a prolonged period of time. The symptoms begin before 30 years of age, cause significant impairment in the patient’s overall level of functioning, and are not feigned or intentionally produced. The patient presents with a specific constellation of symptoms, including four pain symptoms, two gastrointestinal symptoms, one sexual symptom, and one pseudoneurological symptom. The most common symptoms are pain in various parts of the body, dysphagia, nausea, bloating, constipation, palpitations, dizziness, and shortness of breath.113 In pediatric populations, the full diagnostic criteria for somatization disorder are rarely met; however, many children do experience multiple medically unexplained symptoms.

CONVERSION DISORDER

Conversion disorder is characterized by medically unexplained deficits or alterations of voluntary motor or sensory function that is suggestive of a neurological or medical illness. These symptoms are judged to have either been initiated or perpetuated by psychological factors and are preceded by conflicts or other stressors. The symptom or deficit may not include pain, may be under voluntary control, may be intentionally produced or feigned, or may be a culturally sanctioned experience. The symptom or deficit cannot, after appropriate medical investigation, be entirely explained by a neurological or general medical condition or be substance induced. Documented conversion disorder is rare and is reported in fewer than 1% of individuals in community settings. Conversion disorder has been described in children and adolescents as involving a variety of motor and sensory symptoms.114–116

HYPOCHONDRIASIS

The term hypochondriac is commonly used colloquially; however, in order to fulfill the diagnosis of hypochondriasis, an individual must have a persistent preoccupation with fears of having a serious disease that is based on misinterpretation of bodily symptoms in spite of appropriate medical evaluation and reassurance.117 This preoccupation must also cause significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other areas of functioning and must last at least 6 months. The condition cannot be better explained by an alternative psychiatric diagnosis, and may not be to the extent of a delusion. The prevalence is low in the adult population; fewer than 1% of community populations meet full diagnostic criteria.118 There are no published descriptions of hypochondriasis in pediatric patients. The diagnosis would be complicated by the fact that parents are intricately involved in the seeking of health care for their children, as well as by the interpretation of children’s medical symptoms.

UNDIFFERENTIATED SOMATOFORM DISORDER

Undifferentiated somatoform disorder also first appeared in the DSM-IV. The diagnostic criteria include the experience of one or more physical complaints, and the symptoms cannot be fully explained by a general medical condition, or when a medical condition is identified, the impairment is in excess of what would be expected by history, laboratory findings, or physical examination. Furthermore, the symptoms cause clinically significant distress or impairment and have been present for at least 6 months. This category has been particularly criticized because the criteria are overly broad; therefore, many individuals who have physical symptoms with associated disability would fulfill the criteria.112

Assessment of Pain in Children

PAIN-RELATED BEHAVIORS

Observing the child’s behaviors can provide further clues about the location, extent, and severity of the pain. Clearly, behavioral manifestations of pain can be affected by many factors, including pain severity, child’s age, fear and anxiety, past pain experiences, environmental factors (e.g., parent and peer presence), feelings of control, and other factors. For example, a 12-year-old boy who is injured on the soccer field may not demonstrate pain behaviors until he gets into the family car after the game. For these reasons, interpretation of meaning is involved in using behavior to assess pain. Acute pain and anxiety may be responded to behaviorally in a similar manner; these similarities result in debates about whether behaviors related to these two experiences can actually be separately identified or should be combined as “distress” behaviors.119 In addition, with age, children learn how to mute some of their pain-related behaviors, as noted by LeBaron and Zeltzer.120 Thus, for medical procedure–related pain behaviors, younger children may exhibit more crying and kicking, whereas adolescents may be more likely to clench their fists, grimace, and contract other muscles. This difference has affected the results of different behavioral scales used to assess acute pain across a wide age range of children and adolescents.

BEHAVIORAL AND PHYSIOLOGICAL SIGNS

Investigators have devised a range of behavioral distress scales for infants and young children, mostly emphasizing the child’s facial expressions, crying, and body movement. For example, the FLACC scale121 is a 5-item scale that a rater uses to score each of five categories—face (F), legs (L), activity (A), cry (C), and consolability (C)—along a scale from 0 to 2. Facial expression measures appear most useful and specific in neonates and young infants. Autonomic signs can indicate pain but are nonspecific and may reflect other processes, including fever, hypoxemia, and cardiac or renal dysfunction.

SELF-REPORT OF PAIN

Children aged 3 years and older become increasingly articulate in describing intensity, location, and quality of pain. Scales involving drawings, pictures of faces, or graded color intensity have been validated, especially for children aged 5 years and older. For example, excellent psychometric properties have been reported with the Faces Pain Scale–Revised,122 a revised version of a scale originally developed by Bieri and associates.123 It consists of six gender-neutral line drawings of faces that are scored from 0 to 10.

Children’s self-reports of pain can be obtained in the moment by asking about how much pain is currently present; in the past by using retrospective interview methods in which children or parents are asked to recall the frequency, intensity, and duration of pain over an identified time period such as 1 month; or in the future by using prospective monitoring of pain in daily diaries or logs. Because of the potential for children to have recall bias, prospective recording of recurrent or chronic pain complaints is recommended.124 Novel methods have been emerging to enhance compliance in maintaining prospective records, including the use of electronic pain diaries with children.125

PAIN ASSESSMENT IN COGNITIVELY IMPAIRED CHILDREN

The measurement of pain in cognitively impaired children remains a challenge, and methods are being studied to determine ways of assessing pain in this population. There is increasing research on the development of pain assessment tools for understanding pain expression and experience in cognitively impaired children.126–128 Cognitively impaired children may not have the language abilities to provide labels of quantity and quality to describe their pain. They also may not have the mathematical skills needed to rate their pain on the traditional rating scales. Their behavioral responses to pain may also lead to erroneous inferences about their pain. For example, children with Down’s syndrome may express pain less precisely and more slowly than do children in the general population. Pain in individuals with autism spectrum disorders may be difficult to assess because these children may be both hyposensitive and hypersensitive to many different types of sensory stimuli, and they may have limited communication abilities. Readers are referred to the new editions of Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics, 18th edition,129 and Pain in Infants, Children, and Adolescents, 3rd edition,130 for detailed summaries of the different pain assessment tools currently available.

ASSESSMENT OF FUNCTIONAL CONSEQUENCES OF PAIN

Measurements of activity interference, functional disability, and quality of life are important for understanding the specific effects of pain on children. These functional consequences are considered important primary outcomes of pain treatment.34 Validated measures have been developed to capture most of these domains.

There are general measures of disability and quality of life that may be useful for documenting the effect of pain on children’s functioning and well-being. For example, the Functional Disability Inventory35 and the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory131 have been the most widely used instruments to document disability and quality of life of children with chronic pain. Several more recently developed measures also show promise, including a new measure of pain-related activity interference in school age children and adolescents, the Child Activity Limitations Interview,43 and a new composite measure of chronic pain in adolescents, the Bath Adolescent Pain Questionnaire.132 Several measures of function and quality of life have been tailored to assess specific pain syndromes or chronic health conditions. For juvenile arthritis, for example, disease-specific measures of function and quality of life include the Childhood Health Assessment Questionnaire133 and the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory, Rheumatology Module.134

ASSESSMENT OF FAMILY FACTORS

The family has been described as an important context for understanding, assessing, and managing pediatric chronic pain,135 and there is a growing body of research on family and parent factors and their relationship to pain and functional consequences. An integrative model of parent and family factors in pediatric chronic pain and associated disability has been proposed.136 This model situates individual parenting variables (e.g., parenting style, parental reinforcement) within a broader context of dyadic variables (e.g., quality of parent-child interaction) and the more global familial environment (e.g., family functioning). A variety of instruments are available for assessing family variables at each level of assessment (e.g., the Illness Behavior Encouragement Scale137), although none have been widely used in pediatric pain research. Different family variables are important to consider, depending on developmental status of the child. For example, in adolescents with chronic pain, the level of autonomy and conflict in the parent-teenager relationship would represent developmentally relevant domains to consider in family assessment.

CLINICAL EVALUATION OF PAIN

Parents presenting with a child suffering from headaches want not only a diagnosis but also the clinician’s help in reducing the pain and suffering of their child. Narratives are powerful tools with which to learn about a child’s pain problem but also what the child and parents relate to the problem (e.g., the book by Arthur Frank, The Wounded Storyteller,137a provides detail on the narratives of patients and the relationship that develops between patient and health care provider through narrative). The use of pain narratives has been described in children138 as a method of enhancing engagement between patient and provider on the basis of the experience of listening to the storyteller; that is, it is helpful to learn the child and parent’s “stories” of the pain problem. After the child’s and parent’s pain narratives, further questions then can help elucidate the problem and help in planning for the treatment. For example, it would be important to learn what factors make pain worse and what helps, temporal qualities, location of the pain, and description of the pain experience. Through narratives, important differences in the perception of the nature, meaning, or consequences of pain may arise between the stories told by parents and those told by the children. Differences between parents and children in the reports of pain and pain-related disability have been found in several studies.139 By elaborating parent and child interpretations of pain, the clinician may identify important areas for treatment, such as broader issues in parent-child communication.

With headaches, for example, the initial thinking by the clinician during the evaluation should be to rule out something structural in the brain (e.g., tumor, traumatic brain injury), chemical causes (e.g., monosodium glutamate reactions), or other identifiable “causes” that can be readily treated if diagnosed (e.g., sinus infection, poor vision). Clearly, observation and a history of unusual or sudden symptoms or signs—such as fever; morning vomiting; visual disturbances; seizures; paralysis; weakness; loss of sensation; shaking; or any sudden changes in alertness, speech, or thinking, especially after head trauma—would suggest the need for urgent evaluation with further diagnostic tools. However, most children presenting with chronic pain do not have easily identifiable single causes of the pain (e.g., sinus infection) and the longer pain has persisted, the more “baggage” the pain picks up along the way, such as secondary stressors of school absenteeism, muscle tension from restricting the painful body part, and pain-related anxiety. Although it is important to learn as much as possible about the pain, it is just as important to learn about pain-related functional disability; that is, inquiry can be directed to learn to what extent and in what ways the pain is interfering with the child’s daily life, including sleep, appetite, school attendance and performance, social and physical activities, and family life.

The following questions can be asked of the child and parent to learn about the nature of the pain and how it is interfering with the child’s daily life (adapted from Zeltzer and Schlank140).

Does the pain occur at any particular time of day (e.g., when your child [you] first awakens), week (e.g., school days only), or month (with menses, for girls)?

Does the pain occur at any particular time of day (e.g., when your child [you] first awakens), week (e.g., school days only), or month (with menses, for girls)? Did anything new or different, such as attending a new school, precede the pain? What do you think started the pain and what keeps it going?

Did anything new or different, such as attending a new school, precede the pain? What do you think started the pain and what keeps it going? What medications (name, dose, how often and for how long) has your child taken for her pain and what is she still taking (and do they help)? What did not help? (For the child: What do you think helped most?)

What medications (name, dose, how often and for how long) has your child taken for her pain and what is she still taking (and do they help)? What did not help? (For the child: What do you think helped most?) What herbs or nondrug therapies has your child tried for the pain (e.g., warm baths, ice packs, listening to music, physical therapy, massage, yoga, relaxation training, hypnotherapy, acupuncture, psychotherapy)? Did they help? Tell me more (why do you think [this therapy] helped?). (Ask same of child.)

What herbs or nondrug therapies has your child tried for the pain (e.g., warm baths, ice packs, listening to music, physical therapy, massage, yoga, relaxation training, hypnotherapy, acupuncture, psychotherapy)? Did they help? Tell me more (why do you think [this therapy] helped?). (Ask same of child.) What does the pain stop your child (you) from doing (e.g., concentrating, doing homework, attending school, playing sports, attending social activities with friends, attending activities with family)?

What does the pain stop your child (you) from doing (e.g., concentrating, doing homework, attending school, playing sports, attending social activities with friends, attending activities with family)? Does the pain interfere with falling asleep and/or staying asleep? Does your child (you) wake up feeling tired/not rested?

Does the pain interfere with falling asleep and/or staying asleep? Does your child (you) wake up feeling tired/not rested?PSYCHOSOCIAL ASSESSMENT

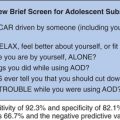

Some clinicians have recommended that psychosocial assessment begin as soon as noncoping occurs,141 meaning that a child begins to miss school or curtail participation in regular activities because of the pain. Although the primary care physician should gather psychosocial information as part of the clinical evaluation of the pain problem, a referral to a psychologist or psychiatrist for a psychosocial assessment can greatly extend this inquiry. We believe the process of how the physician makes the referral for a psychosocial assessment is critical to the subsequent acceptance of psychological conceptualizations for symptoms and to management approaches and thus should be done with appropriate care. Patients and their families are more likely to accept a psychological referral and not feel abandoned by their physician if it is presented early and as a routine procedure in all cases of persistent pain causing disruption of normal activities. It is crucial that professionals avoid dichotomization between organic and psychogenic causes of pain28 and to present the psychosocial assessment along with the physical investigation and follow-up. This procedure avoids the trap of waiting for psychosocial assessment as a last resort after all other physical attempts to understand the problem have failed.

Psychosocial assessment may consist of clinical interviews, record keeping, and observation of the interaction among family members. In detailed clinical interviewing, the clinician should assess developmental, behavioral, or psychiatric concerns in the patient’s and family’s history and should identify potential stressors and areas of maladaptive coping with regard to academic success, relationships, school absenteeism, and social activities. Observation and direct questioning concerning the roles of various family members toward pain and its management can uncover maladaptive patterns in how family members respond to the child’s pain. Information concerning the parents’ own emotional functioning, anxiety, and marital stress may also contribute to a more complete understanding of sources of stress within the child and family. Diaries and standardized self-report measures help provide information about the child’s subjective experience of pain and may also provide information on the child’s motivation and attitude toward pain treatment.

CLINICAL EVALUATION OF SOMATOFORM DISORDERS

The diagnostic process for somatoform disorders involving pain complaints requires a quantification of the patient’s pain, including how intense the pain is, when it occurs, its location, and its quality. Whenever possible, self-reports should be performed outside of the parents’ presence, because children may hide or, alternatively, exaggerate pain in their parent’s presence, and parental objectivity may be compromised. Pain disproportionate to the organic etiology does not alone establish the diagnosis. Positive evidence for the existence of psychological factors must be demonstrated to explain the patient’s pain. Evidence that would support the diagnosis from a psychological point of view might include the onset of pain after a specific stress or trauma, disability that is disproportionate to the reported pain, and exacerbations that are predictably linked to stressful events or clear secondary gain. All of these factors should be independently assessed, as well as assessed with regard to the effect each factor has on the child’s level of functional impairment or distress.

In their management model for pediatric somatization, Campo and Fritz27 offered seven useful guidelines for assessment in the context of suspected somatization: (1) acknowledge patient suffering and family concerns; (2) explore prior assessments and treatment experiences; (3) investigate patient and family fears provoked by the symptoms; (4) remain alert to the possibility of unrecognized physical disease, and communicate an unwillingness to prejudge the origin of the symptom; (5) avoid excess and unnecessary tests and procedures; (6) avoid diagnosis by exclusion; and (7) explore symptom timing, context, and characteristics.

Standardized measures may provide useful information about children’s specific somatic symptoms, as well as their level of functional disability. For example, the Children’s Somatization Inventory79 is a self-report instrument of somatic symptoms experienced by children and adolescents over a 2-week period. This may yield a quick and helpful overview of somatic symptoms. Functional disability can be assessed with the Functional Disability Inventory,35 which provides information on the child’s difficulty performing common physical and recreational activities.

RESEARCH ISSUES AND CONTROVERSIES

Diagnosis and assessment of pain conditions and somatoform disorders involves taking a comprehensive biopsychosocial perspective. Within the somatoform disorders, there remains controversy over nosology, and future research efforts focused on clarifying symptoms in children and adolescents will increase the relevance of this diagnostic category in pediatrics. There are some areas of pain assessment that are much further developed than others. For example, tremendous research attention has been devoted to devising developmentally appropriate rating scales for assessing pain intensity in children of various ages. However, much less attention has been devoted to validating measures of physical or emotional functioning in children with chronic pain. There has been movement in the pain field toward common assessment instruments to document patient response to treatment. The Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials (IMMPACT) has accomplished this for adults, recommending a set of core domains to be considered in clinical trials of chronic pain in adults142 and specific measures to assess each of these domains.143 A similar effort is under way in pediatric pain (PedIMMPACT) with a current draft of a set of domains and recommended assessment tools to consider in all clinical trials involving pediatric acute or chronic pain.144 These efforts should greatly extend clinicians’ ability to synthesize research findings and make treatment decisions.

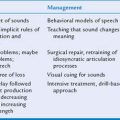

TREATMENT STRATEGIES FOR PAIN AND SOMATOFORM DISORDERS

This chapter is not intended to provide an exhaustive review of pediatric pain treatment strategies. More comprehensive reviews of treatments for specific pain conditions in children (disease-related pain,145 migraine,146 recurrent abdominal pain,147 and chronic nonmalignant pain148) are available elsewhere. The reader is also referred to several published clinical practice guidelines available from the American Pain Society for the management of pain conditions in children, including for fibromyalgia pain,108 sickle cell disease pain,149 cancer pain,150 and juvenile chronic arthritis.103

Management of Procedural Pain

A growing body of research has focused on the best ways to help children cope with and manage pain related to invasive procedures. In the 1980s, much of the treatment research was focused on children undergoing more extensive invasive procedures such as bone marrow biopsy and lumbar puncture. However, children now routinely undergo these procedures under sedation or general anesthesia,151 with a corresponding reduction in the experience of pain and distress. Cutaneous procedures such as venipuncture for intravenous administration and intramuscular injections for immunizations are anxiety provoking for children and caregivers alike, and there are a variety of pharmacological agents, as well as psychological techniques, that have shown to be useful to assist children in coping with these necessary painful events.

Topical local anesthetics have been used to help prevent or alleviate skin pain associated with needle puncture and venous cannulation. A variety of local anesthetics have been studied, and although none have become the standard of care, there is a large body of evidence that different agents and methods of delivery can effectively decrease procedural pain (reviewed by Houck and Sethna152). Topical anesthetics such as lidocaine (ELA-Max), lidocaine-prilocaine (EMLA), liposomal lidocaine 4% cream, vapocoolant spray, iontophoresis, and amethocaine have all been evaluated. The application of topical anesthetic creams, such as EMLA, has been shown to help reduce pain that children experience but remains underused, primarily because of their slow analgesic onset (60 to 90 minutes for EMLA) and inconsistent effectiveness. Advances in transdermal delivery technology have led to the emergence of a number of new delivery approaches that accelerate the onset time to 20 minutes or less and provide more consistent and deeper sensory skin analgesia. Although still in the early stages of investigation, transdermal delivery of local anesthetics shows promise. The use of topical anesthetic techniques for cutaneous procedural pain in children continues to be an active area of research as new agents and methods of delivery are developed. However, even with adequate analgesia from a topical anesthetic, it is still important for medical professionals to consider incorporating behavioral methods (such as coaching and distraction) to assist children who may still experience significant behavioral distress.

Psychological treatments to aid children in coping with invasive procedure pain have also been extensively reviewed.94 Cognitive-behavioral techniques have been identified as a well-established treatment for procedure-related pain in children and adolescents.153 Treatment includes various components such as breathing exercises, progressive muscle relaxation, positive mental imagery, filmed modeling, reinforcement/incentive, behavioral rehearsal, cognitive distraction, counterconditioning, and active coaching by a psychologist, parent, and/or medical staff member. Each of these techniques must be developmentally appropriate for the child. Techniques such as listening to music, watching videos, playing videogames, counting objects in the room, playing with toys or puppets, and reading books are a few of the many distraction modalities that have been shown to effectively decrease pain and distress in children undergoing injections, immunizations, and chemotherapy.154 Discrimination training has been described as a useful treatment strategy for infants undergoing frequent invasive procedures. Visual and auditory signals can be used to let an infant know that an invasive procedure is about to occur and then immediately after the procedure the signal can be turned off to let the child discriminate “safe” times.154

Management of Disease-Related Pain

The management of pain related to a chronic health condition such as sickle cell disease, IBD, juvenile arthritis, and cancer involves largely medical management of the underlying condition. For example, treatment of IBD is aimed at reducing inflammation in the colon, usually by specific anti-inflammatory medication, which often reduces pain symptoms. Ongoing assessment, treatment, and, when possible, prevention of pain should be the rule for management of disease-related pain. Pain that persists beyond aggressive medical management may necessitate separate intervention. Moreover, the clinician should consider nonpharmacological strategies to improve coping and reduce pain (e.g., hypnotherapy, biofeedback). Several examples of treatment strategies for disease-related pain are offered in this section.

CANCER PAIN

Cancer pain in children is different from that experienced by adults because different types of cancer afflict children and adults and because the treatment protocols for their cancer are different. For example, children being treated for cancer commonly experience mucositis, stomatitis, and neuropathic pain from chemotherapy. The focus of pain treatment is twofold: (1) the pain caused by the neoplasm and (2) the pain caused by the treatment of the cancer. Both pharmacological and psychological treatment modalities have been investigated. Pharmacological pain management focuses mainly on analgesic drugs, such as ibuprofen, acetaminophen, and opioids; on tricyclic antidepressants; and on anticonvulsant medications. Although much research attention has been devoted to nonpharmacological management of procedural pain related to cancer treatment, only a handful of studies on nonpharmacological treatments for other types of cancer pain have been conducted to date. In a few case studies, researchers have investigated the use of hypnosis and imagery for management of cancer pain in children. However, there are currently no empirically validated psychological treatments for pediatric cancer–related pain.145

MUSCULOSKELETAL DISORDERS

Management of musculoskeletal disorders such as juvenile arthritis and hemophilic arthropathy has focused on anti-inflammatory drugs, as well as opioids and tricyclic antidepressants, with varying degrees of success. Treatments may differ, depending on the activity of the disease. In small trials of cognitive-behavioral therapy, children with arthritis were taught progressive muscle relaxation, guided imagery techniques with distraction, and methods of “blocking” transmission of pain messages.155 Cognitive-behavioral interventions combined with antidepressant agents are currently being investigated in the treatment of juvenile fibromyalgia.

SICKLE CELL DISEASE