13 Pain

Pain is a totally subjective phenomenon. It is the product of a noxious stimulus, which evokes a response in the patient. That response is predicated by the patient’s pain tolerance and psychological state at the time of stimulation. What represents debilitating pain for one patient may be largely ignored by another.

More recently, there has emerged the concept of ‘neuropathic pain’ with an inherent grading system that allows cross-referencing for research as well as clinical purposes.1 The working definition of neuropathic pain is pain provoked by a lesion or disease affecting the somatosensory system. The problem with such a definition is that it could, for all practical purposes, encapsulate all pain syndromes thereby making it less than specific.

Some authors have tried to differentiate chronic pain from neuropathic pain, citing prevalence rates of 20–30% for the former and 5–7% for the latter.2 Others just divide pain into acute and chronic with claim of distinctive characteristics for each, and different approaches to management (see Table 13.1).

TABLE 13.1 Differentiating acute and chronic pain

| Characteristic | Acute pain | Chronic pain |

|---|---|---|

| Duration | ≤ 2 weeks | > 3 months |

| Associated features | Tachypnoea Tachycardia Sympathetic autonomic release (fright/flight) |

No sympathetic features Local reaction (e.g. swelling, skin changes) |

| Effects on quality of life | Little to none | Significant |

| Altered behaviour | Little to none | Significant |

| Management | Primarily pharmacological | Multidisciplinary team approach (beyond pharmacological) |

This chapter will examine the approach to pain management and provide useful tips to help the general practitioner cope with the patient in pain. As with so many areas of medicine, and neurology in particular, there has been a concerted effort to classify various conditions to enhance international collaboration and consensus. This is equally true for pain3 but application of these classifications contributes little to coalface general practice and will not be further reviewed in this chapter.

History

The fact that pain may provide the presenting complaint for psychological problems does not negate the fact that the pain is still felt. Pain is a very subjective phenomenon and may follow very specific patterns that go hand-in-glove with specific complaints. The symptom constellation will provide the diagnosis (see Table 13.2).

| Diagnosis | Classical symptoms |

|---|---|

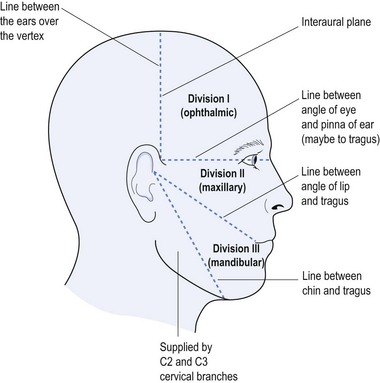

| Trigeminal neuralgia (tic douloureux) | Sharp stabbing pain in the face (jabs of pain) Pain triggered by chewing, cleaning teeth, cold air Pain within the distribution of maxillary branch of CNV shooting from the jaw upwards |

| Glossopharyngeal neuralgia | Stabbing pain similar to trigeminal neuralgia Pain usually shoots into back of tongue Pain may shoot into ipsilateral ear |

| Temporomandibular (TM) joint dysfunction | Pain localised in face Pain may be in TM joint Pain provoked by chewing Aware of clicking in TM joint |

| Atypical facial pain | Pain in the face that does not fit other diagnoses of unilateral face pain |

| Post-herpetic neuralgia | History of herpes zoster infection Pain follows distribution of a cranial nerve or nerve root |

| Radicular pain | Pain corresponding to the distribution of a nerve root |

As with all neurology, there are certain questions that need to be asked: When did the pain start? Was there a provocative incident that caused the pain? Where is the pain? Are there precipitating or relieving factors? What is the nature of the pain? Are there associated features with the pain? What is the frequency and duration of the pain? A perfect example of how these questions provide diagnostic answers is found in Chapter 6 on headache. It is these questions that differentiate tension-type headache from migraine.

Certain conditions, such as diabetes with peripheral neuropathy and diabetic amyotrophy, may provoke very severe pain symptoms. Pain is a particular feature of small fibre diabetic sensorimotor neuropathy. From the neurological perspective, pain in the head, neck, back and limbs may be of primary neurological origin. Pain in the thorax or abdomen is almost always a feature of a visceral disorder rather than primary neurological complaint, for instance, spinal or radicular pathology, thus dictating an alternative investigational paradigm to the diagnosis of thoraco or abdominal pain. There are some exceptions, such as herpes zoster infection with shingles (and post-herpetic pain) and diabetic radiculopathy, already identified.

Pain evokes its own set of jargon and possible confounding language, which may lead to confusion. Thankfully much of this jargon has not yet found its way into common daily language and so is largely ignored by patients (see Table 13.3).

TABLE 13.3 Glossary of pain jargon

| Term | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Allodynia | Pain perceived following non-noxious, innocuous stimulus (e.g. light touch causes burning pain) |

| Antalgia (antalgic) | Pain perception (noun), pain provoked action (adjective) (e.g. antalgic gait—altered gait due to the influence of pain) |

| Dysaesthesia | An altered perception of sensation with abnormal (often unpleasant) feeling associated with stimulation, such as touching over the affected area causes ‘strange feeling’ |

| Hypaesthesia / hypoaesthesia | Reduced perception of stimulus (both words are interchangeable) |

| Decreased sensation | |

| Hyperalgesia | Increased perception of pain |

| Hyperaesthesia | Increased perception of stimulus (need not be pain) |

| Hyperpathia | Decreased sensation to one or more modalities while concurrently having increased perception of pain (hyperalgia) or pain with innocuous stimulation (allodynia) |

| Hypoalgia | Reduced perception of pain |

| Paraesthesia | Abnormal sensations, such as ‘pins and needles’, tingling, pricking, reduced or even loss of sensation. It implies abnormality anywhere along the sensory pathway from peripheral nerve to sensory cortex—the epitome of ‘neuropathic pain’ |

The concept of paraesthesia (see Table 13.3) may be short-lived with no real consequence (as in ‘my foot went to sleep with pins and needles’). It may reflect altered blood supply to a target region. This produces neurological symptoms but should not dictate neurological consultation. A perfect example of this is the symptom attached to carpal tunnel syndrome with paresthesia in the fingers. This responds favourably to night splinting to obviate palmar–flexion of the wrist, which compromises blood supply to the median nerve (see Ch 11). Where paresthesia persists, it is a warning of abnormality somewhere within the sensory pathway and may dictate additional investigations, such as nerve conduction studies or sensory evoked potential studies and hence referral to a specialist.

Reflex sympathetic dystrophy or complex regional pain syndrome

Reflex sympathetic dystrophy (RSD) or complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) is a refractory pain syndrome in which the term RSD is being replaced with CRPS, as it is neither a true ‘reflex’ nor a ‘dystrophy’. It is a type of limb pain characterised by: disproportional pain (both in character and distribution); allodynia (see Table 13.3); altered limb function (accompanied by antalgic movements); oedema; discolouration (often cyanotic); altered temperature; possible sweating; and maybe dystonia or spasms; or altered anatomy (with nail changes, hair loss, skin thinning or bone demineralisation).

Other terms often also included within the CRPS spectrum include: causalgia; post-traumatic pain syndrome; Sudeck’s atrophy; reflex neurovascular dystrophy; post-traumatic spreading neuralgia, sympathalgia and shoulder–hand syndrome.4 CRPS represents regional pain of uncertain pathophysiology, which usually affects the hand or foot but may also involve or spread to other parts of the body.

Spinal pain

As with the classification of pain in general3 there have also been attempts to classify spinal pain,5 but again this has relevance to international collaboration and less application to the family physician.

What is of value is to determine where in the spine the pain is generated, the level and extent of injury. It helps to determine if the pain is of neurological (nerve) origin or musculoskeletal (bone and muscle derived). This will have direct implication on both choice of investigation and the consultant most appropriate should referral be required. In some cases, the rheumatologist may be preferred over the neurologist.

Some helpful tips for the general practitioner may include description of pain and its distribution, such as neck pain, which may be limited to the neck but have associated neurological signs, such as pain radiation specific to a given nerve root or complex. Such neurological pain includes: radicular pain with sciatica or specific finger involvement that does not respect either ulnar or median nerve distribution; muscle wasting or weakness referrable to a given nerve root; loss of deep tendon reflexes at the level of the damage and hyperreflexia below the spinal level (see Ch 4); or pain exacerbated by coughing, sneezing or straining.

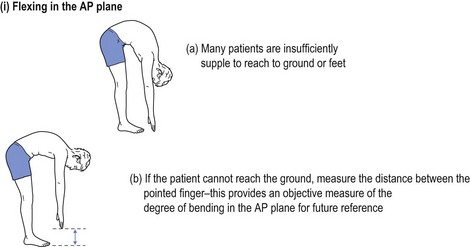

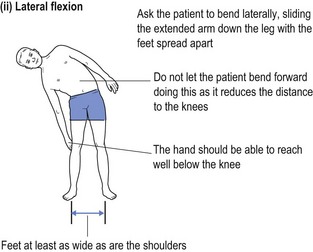

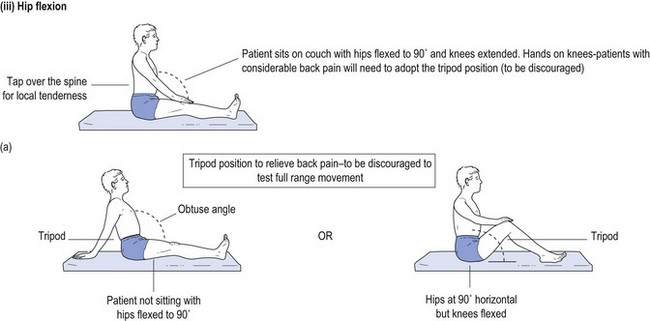

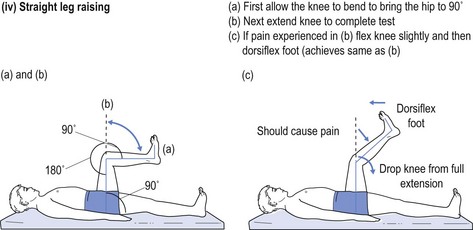

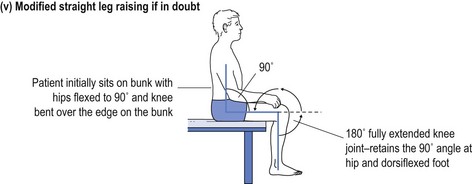

One cannot ignore the need for a proper physical examination to determine the range of spinal movement, be it of the neck or the lower back. The patient is asked to touch their toes from the standing position; to slide down the lateral border of the leg with lateral flexion rather than bending forward; to sit on the couch with hands on knees and hips flexed to 90° while the doctor taps over the spine to identify localised discomfort; and to undergo straight leg raising (see Fig 13.1).

FIGURE 13.1 (i) Testing lower spinal movement—flexing in the AP plane. (ii) Testing lower spinal movement—lateral flexion. (iii) Testing lower spinal movement—hip flexion. (iv) Testing lower spinal movement—straight leg raising. (v) Testing lower spinal movement—modified straight leg raising if in doubt.

Straight leg raising is an alternative test for forward flexion in the AP plane (see Fig 13.1(i)) as is sitting on the bunk with hips at flexed at 90° (see Fig 13.1(iii)) while avoiding the tripod position. This can be administered in various guises, as shown in Figure 13.1(iv) and (v). This tests both the validity of the findings and their reliability, if producing the same results irrespective of the method used. Where the results of various methods of testing the same modality are in conflict, it provides strong evidence of a non-organic basis for the complaint. This should alert the clinician to delve further into the psyche (see Ch 5). It may alert the doctor to question the real reason for presentation, which might be anything from a subconscious call for help to a claim for compensation.

Neck movement is tested in different planes: asking the patient to touch the ear on the ipsilateral shoulder; the chin on the shoulder (both sides); fully flex the neck in the AP plane to touch the anterior chest wall; and then to fully extend the neck. This should be objectively recorded and provides objective evidence of range of neck mobility, which may give an important clue to the origin of the pain.

The examination of the spine, re pain, is not complete without a full peripheral neurological examination (see Ch 4). Completely normal upper limb examination (or even features of lower motor neurone deficit) in the upper limb, with upper motor neurone signs in the lower limb (see Ch 4) localises the lesion to either below, or at, the cervical level and above the lumbar spine. Lower motor neurone features in the lower limb also localise the damage to the lumbar spine.

Trigeminal neuralgia

Trigeminal neuralgia6 (tic douloureux) produces paroxysmal jabbing, unilateral facial pain provoked by innocuous stimuli, such as chewing, brushing teeth, touching the face or a gust of wind on the face. Often the cause is unknown but it may accompany multiple sclerosis, the compressive effect of a tumour or even infection, such as chronic meningitis. Current theory favours pain consequent to an aberrant blood vessel stimulating the branch of the trigeminal nerve within the skull, but this is rarely confirmed on imaging.

Temporomandibular joint dysfunction

This is known as TM joint dysfunction7 and includes nocturnal bruxism (so called ‘fang grinders’), TM joint malocclusion, and what some refer to as myofacial syndrome. This must be differentiated from ‘claudication of the jaw’, which may occur in the elderly with temporal arteritis.

This approach often obviates the need to involve a neurologist, who would likely follow the same approach as first-line therapy by advocating referral to a dentist. The role of the specialist emerges if this does not provide the answer, raising concerns about the diagnosis. One differential diagnosis is glossopharyngeal neuralgia, which produces a pain not dissimilar to a combination of trigeminal neuralgia and TM joint dysfunction, but often includes a lancinating pain shooting through the ipsilateral ear. Its treatment largely mirrors that of trigeminal neuralgia but the fun, that is medicine, is the academic satisfaction of making the correct diagnosis even if it does not change treatment, especially if it also does not cause further inconvenience or cost.

Post-herpetic neuralgia

Post-herpetic neuralgia has been treated with a number of approaches8 but the principle to management remains the same. The pain needs to fit the accepted pattern: lasting in excess of three months from the bout of shingles; occurring in the route of the dermatome; possible decreased sensation within the distribution of the dermatome; and hyperaesthesia (see Table 13.3) at the transitional borders of the dermatome. The pain may be both deep and superficial with super-added tic-like lancinating pain.

First-line treatment may include application of topical remedies, such as capsaicin ointment, as a counter irritant, or even a xylocaine ointment or cream. This may be complemented with either tricyclic antidepressants (amitriptyline or imipramine) or AEM, such as CBZ, starting with a dosage of 400 mg of the controlled-release formulation b.d. and increasing the dose to mirror the therapeutic levels accepted for epilepsy treatment (see Ch 7). If first-line treatment fails, it may be worth considering a course of steroids, tapering from 75 mg prednisolone per day to nothing over a two-week period. Off-license use of some of the previously cited agents (see trigeminal neuralgia above) may be of help but would justify referral to a consultant.

Conclusion

Pain is a massive topic to cover in such a brief overview. It reflects the idiosyncratic nature of the individual patient, and the approach to treatment is as variable as the background of the patient and the doctor. This review has not even touched on cultural and educational influences that may impact on the management of pain, or the use of traditional remedies, such as acupuncture or herbal treatments, which may have a place but are outside the scope of this book. Hypnosis may be an effective tool, and personal experience has taught that it is very effective when undergoing dental treatment or managing refractory head pain. If using hypnosis, it is imperative to include a protective post-hypnotic suggestion that if pain is providing a protective warning then the patient will still appreciate that warning, even if the severity of the pain is alleviated.

The principal message is that if pain does not respond to simple intervention with analgesics or non-steroidal agents, then it justifies further investigation and possible involvement of a consultant. Where the root cause for the pain is obscure, the involvement of a consultant may be warranted but the family doctor may be the best placed to recognise non-organic causes for pain. There may be unequivocal signs of non-organic disease (see Ch 5), which should not be overlooked because early intervention enhances prognosis. Pain is a common cause for depression and behaviour problems that may cause altered domestic dynamics, which impact negatively on quality of life. The general practitioner is by far the best placed to recognise these issues and to deal with them. As has been repeatedly stated in this book, the best management of pain syndromes is achieved by a close working relationship between general practitioner and consultant. Where this has proven ineffective in pain management, it may be time to involve a multidisciplinary team,9 be that within a rehabilitative framework or a recognised pain clinic. Pain is so intrusive that it is sometimes better to call for help early, rather than to allow the establishment of entrenched pain-provoked behaviour.

1 Treede RD, Jensen TS, Campbell JN, et al. Neuropathic pain: redefinition and a grading system for clinical and research purposes. Neurology. 2008;70:1630-1635.

2 Bouhassira D, Lantéri-Minet M, Attal N, et al. Prevalence of chronic pain with neuropathic characteristics in the general population. Pain. 2008;136:380-386.

3 Merskey H, Bogduk N. Classification of chronic pain, 2nd ed. IASP: Seattle; 1994.

4 Ghai B, Dureja P. Complex regional pain syndrome: a review. J of Postgraduate Medicine. 2004;50(4):300-307.

5 Cardenas DD, Turner JA, Warms CA, Marshall HM. Classification of chronic pain associated with spinal cord injuries. Archives of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. 2002;83:1708-1714.

6 Gronseth G, Cruccu G, Alksne J, et al. Practice parameter: the diagnostic evaluation and treatment of trigeminal neuralgia (an evidence-based review). Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the European Federation of Neurological Societies. Neurology. 2008;71(15):1183-1190.

7 Lobbezoo F, Drangsholt M, Peck C, et al. Topical review: new insights into the pathology and diagnosis of disorders of the temporomandibular joint. J of Orofacial Pain. 2004;18(3):181-191.

8 Argoff CE, Katz N, Backonja M. Treatment of postherpetic neuralgia: a review of therapeutic options. J of Pain Symptom Management. 2004;28(4):396-411.

9 Guzman J, Esmail R, Karjalainen K, Malmivaara A, Irvin E, Bombardier C. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for chronic low back pain: systemic review. British Medical J. 2001;322:1511-1516.