Chapter 10 Pain

Pain assessment

Assessment of children

Physiology and treatment of pain

Pathophysiology

Pain in neonates

Techniques in pain treatment

Combination analgesia

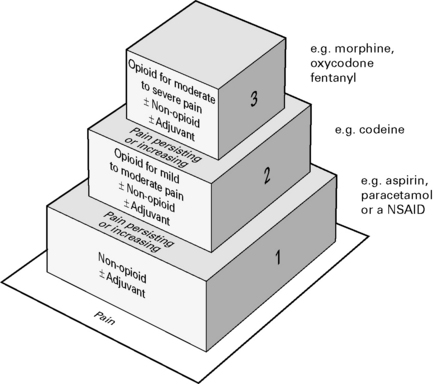

Combinations of opioids, NSAIDs and nerve blocks result in improved pain relief and fewer adverse side-effects. Most effective to use a combination strategy using multimodal drugs of increasing potency (Fig. 10.3).

Specific drugs

NSAIDs

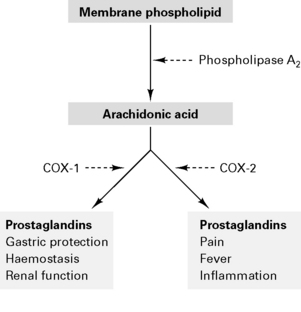

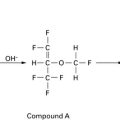

NSAIDs are analgesic, anti-inflammatory and antipyretic. Act to inhibit cyclo-oxygenase in the spinal cord and periphery to decrease prostanoid synthesis and diminish post-injury hyperalgesia at these sites. NSAIDs reversibly inhibit cyclo-oxygenase to reduce prostaglandin and thromboxane synthesis (Fig. 10.4). Type 1 cyclo-oxygenase (COX-1) is present in gastric mucosa to produce protective prostaglandins and modulates renal function and platelet adhesiveness. Type 2 cyclo-oxygenase (COX-2) is responsible for inflammatory prostaglandins. Drugs which inhibit only COX-2 (rofecoxib, parecoxib) cause fewer gastric, renal and haemorrhagic side-effects. NSAIDs also inhibit neutrophil activation by inflammatory mediators and act centrally on the thermoregulatory centre. There is minimal protein binding with subsequent large volume of distribution.

Side-effects

Guidelines for the Use of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs in the Perioperative Period

Opioids

Opioid receptors are found in high concentrations in the limbic system and spinal cord:

Actions

Nausea and vomiting prevent oral intake. Poor bioavailability because of first pass.

Sublingual. Systemic absorption avoids first pass. Dry mouth reduces absorption.

Transdermal. Rate of absorption ∝ lipid solubility. Reduced absorption with vasoconstriction.

Intra-articular. Action via intra-articular opioid receptors.

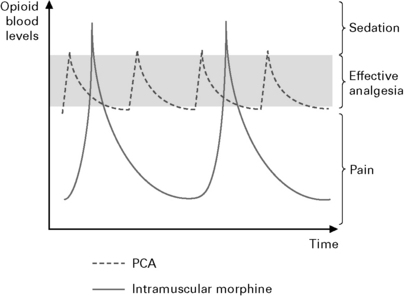

Patient controlled analgesia (Fig. 10.5).

MHRA Guidance 2007

α2-Agonists (e.g. clonidine)

α2-agonists have the following characteristics:

Chronic pain

Reflex sympathetic dystrophy

Postoperative pain

Audit Commission 1997

Findings

www.aagbi.org/publications/guidelines/docs/epidanalg04.pdf. Reproduced with the kind permission of the Association of anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland.

Bridges D., Thompson S., Rice A. Mechanisms of neuropathic pain. Br J Anaesth. 2001;87:12-26.

Carr D.B., Goudas L.C. Acute pain. Lancet. 1999;353:2051-2058.

Cervero F., Laird J.M.A. Visceral pain. Lancet. 1999;353:2145-2148.

Collett B.J. Chronic opioid therapy for non-cancer pain. Br J Anaesth. 2001;87:133-143.

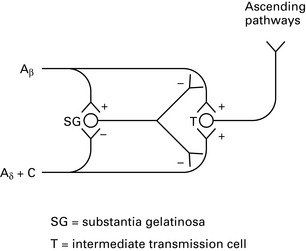

Dickenson A.H. Gate control theory of pain stands the test of time. Br J Anaesth. 2002;88:755-756.

Freynhagen R., Bennett M.I. Diagnosis and management of neuropathic pain. BMJ. 2009;339:391-395.

Gajraj N.M. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors. Anesth Analg. 2003;96:1720-1738.

Grass J.A. Patient-controlled analgesia. Anesth Analg. 2005;101:S44-S61.

Harden R. Complex regional pain syndrome. Br J Anaesth. 2001;87:99-106.

Kharasch E. Perioperative COX-2 inhibitors: knowledge and challenges. Anesth Analg. 2004;98:1-3.

Kidd B.L., Urban L.A. Mechanisms of inflammatory pain. Br J Anaesth. 2001;87:3-11.

Kong V.K.F., Irwin M.G. Gabapentin: a multimodal perioperative drug? Br J Anaesth. 2007;99:775-786.

Kuhn S., Cooke S., Collins M., et al. Perceptions on pain relief after surgery. BMJ. 1990;300:1687-1690.

Lambert D.G. Capsaicin receptor antagonists: a promising new addition to the pain clinic. Br J Anaesth. 2009;102:156-167.

Lynch L., Simpson K.H. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation and acute pain. BJA CEPD Rev. 2002;2:49-52.

Macintyre P.E. Safety and efficacy of patient-controlled analgesia. Br J Anaesth. 2001;87:36-46.

Macrae W.A. Chronic post-surgical pain: 10 years on. Br J Anaesth. 2008;101:77-86.

Maze M., Kamibayashi T. Clinical uses of α2 adrenergic agonists. Anesthesiology. 2001;92:934-936.

McQuay H.J., Poon K.H., Derry S., et al. Acute pain: combination treatments and how we measure their efficacy. Br J Anaesth. 2008;101:69-76.

Nikolajsen L., Jensen T.S. Phantom limb pain. Br J Anaesth. 2001;87:107-116.

Nurmikko T.J., Eldridge P.R. Trigeminal neuralgia – pathophysiology, diagnosis and current treatment. Br J Anaesth. 2001;87:117. 132w

Petrenko A.B., Yamakura T., Baba H., et al. The role of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors in pain: a review. Anesth Analg. 2003;97:1108-1116.

Royal College of Anaesthetists. Guidelines for the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the perioperative period. London: Royal College of Anaesthetists, 1998.

Royal College of Surgeons of England and Royal College of Anaesthetists. Commission on the Provision of Surgical Services, Report of the Working Party on Pain after Surgery. London: HMSO, 1990.

Stone M., Wheatley B. Patient-controlled analgesia. BJA CEPD Rev. 2002;2:79-82.

Walker S.M. Pain in children: recent advances and ongoing challenges. Br J Anaesth. 2008;101:101-110.

White P.F. The role of non-opioid analgesic techniques in the management of pain after ambulatory surgery. Anesth Analg. 2002;94:577-585.World Health Organisation Pain Relief Ladder. http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/painladder/en.

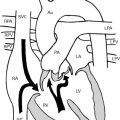

Epidural and spinal anaesthesia

Anatomy

Boundaries of the epidural space are:

Epidural space contains dural sac, spinal nerve roots, spinal arteries, venous plexus, fat and lymphatics. It is widest in the mid-lumbar region (5–6 mm) and narrows cranially to 1.5–2 mm in the lower cervical spine. Veins are valveless; therefore fluid/air injected into vein passes to intracerebral vessels. Veins drain via azygous vein to IVC. Vena caval obstruction, e.g. pregnancy, distends veins. Intervertebral foramina smaller and calcified in the elderly; therefore smaller volumes of LA required.

When supine, highest point on curve of spine is at L3; lowest point is at T6.

Indications for regional anaesthesia

Cardiac disease

Avoids haemodynamic response to intubation and hypotensive effects of induction and maintenance agents. Can therefore give greater haemodynamic stability than GA for patients with ischaemic heart disease or failure if managed carefully. May reduce early postoperative mortality compared with GA in high-risk patients. Not shown to reduce reinfarction rate compared with GA, but when used for general and vascular surgery, may reduce postoperative cardiac failure (Yeager et al 1987).

Other advantages of regional anaesthesia

Yeager et al (1987) investigated 53 high-risk patients. One group had epidural with LA combined with light GA, while a second group had GA with high-dose fentanyl. Postoperative analgesia was given with i.m./i.v. opioids ± epidural. Those with epidural had significantly reduced postoperative complications, cardiovascular failure, infection and hospital costs.

Contraindications

Epidural

Methods of detecting the epidural space

Midline approach results in the needle entering the epidural space where epidural veins are the least dense.

Factors affecting block

Height. Increased dose, but poor correlation with height.

Weight. Lower blocks in obese patients if performed erect, but not if performed while supine.

Total amount (mg) of drug. Determines level of sensory block, rate of onset and duration of block.

Concentration of drug. Determines level of motor block.

Carbonation reduces the latency and increases the duration of block by decreasing intraneuronal pH:

Pharmacokinetics and dynamics

Ropivacaine

Ultrasound-Guided Catheterization of the Epidural Space

Good Practice in the Management of Continuous Epidural Analgesia in the Hospital Setting

Royal College of Anaesthetists 2004

The potential complications of continuous epidural analgesia include:

Complications of spinal/epidural anaesthesia

Headache

Neural damage

More common if associated with paraesthesia during puncture or local anaesthetic injection.

Other complications

Horner’s syndrome. Sympathetic blockade presumed due to tracking of LA.

Shivering. Reduced by warming i.v. solutions and adding fentanyl to the LA.

Urinary retention. Attributed to loss of bladder sensation but still occurs if sensation intact.

Foreign body. Breakage of catheter. Shearing of catheter if withdrawn back through the needle.

Prolonged labour. Most studies show an increased risk of instrumental delivery of LSCS.

Major Complications of Central Neuraxial Blocks (CNB)

Royal College of Anaesthetists 2009

Summary

Interpretation of results

Ballantyne J.C. Does epidural analgesia improve surgical outcome? Br J Anaesth. 2004;92:4-6.

Cook T.M., Counsell D., Wildsmith J.A.W. on behalf of the Royal College of Anaesthetists Third National Audit Project: Major complications of central neuraxial block: report on the Third National Audit Project of the Royal College of Anaesthetists,. Br J Anaesth. 2009;102:179-190.

Grewal S., Hocking G., Wildsmith J.A.W. Epidural abscesses. Br J Anaesth. 2006;96:292-302.

Guay J. The epidural test dose: a review. Anesth Analg. 2006;102:921-929.

Liu S.S., McDonald S.B. Current issues in spinal anesthesia. Anaesthesiology. 2001;94:888-906.

NICE. Ultrasound-guided catheterisation of the epidural space. Interventional procedure guidance, vol 249. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, London, 2008. www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/IPG249Guidance.pdf.

Rao T.L., El-Etr A.A. Anticoagulation following placement of epidural and subarachnoid catheters: an evaluation of neurologic sequelae. Anesthesiology. 1981;55:618-620.

Rathmell J.P., Lair T.R., Nauman B. The role of intrathecal drugs in the treatment of acute pain. Anesth Analg. 2005;101:S30-S43.

Royal College of Anaesthetists. 3rd National Audit Project. Major complications of central neuraxial blocks. Royal College of Anaesthetists, London, 2009. www.rcoa.ac.uk/docs/NAP3_Exec-summary.pdf.

Royal College of Anaesthetists, et al. Good practice in the management of continuous epidural analgesia in the hospital setting. Royal College of Anaesthetists, London, 2004. www.aagbi.org/publications/guidelines/docs/epidanalg04.pdf.

Sharpe P. Accidental dural puncture in obstetrics. BJA CEPD Rev. 2001;1:81-84.

Stone M., Wheatley B. Patient-controlled analgesia. BJA CEPD Rev. 2002;2:79-82.

Walker S.M., Goudas L.C., Cousins M.J., et al. Combination spinal analgesic chemotherapy: a systematic review. Anesth Analg. 2002;95:674-715.

Wheatley R.G., Schug S.A., Watson D. Safety and efficacy of postoperative epidural analgesia. Br J Anaesth. 2001;87:47-61.

Whiteside J.B., Wildsmith J.A.W. Spinal anaesthesia: an update. Contin Educ Anaesth, Crit Care Pain. 2005;5:37-40.

Yeager M.P., Glass D.D., Neff R.K., et al. Epidural anesthesia and analgesia in high-risk surgical patients. Anesthesiology. 1987;66:729-736.