Pain

What is pain?

Pain is highly complex with many interactive dimensions, including physiological, sensory, affective, cognitive, behavioural and psychosocial. The evidence base related to pain is often confusing for the novice therapist because of the different terminology used in different areas of speciality and a lack of clarification between types of pain, the physiological processes involved and the signs and symptoms presented. This section will attempt to summarize the issues surrounding pain, related to the neurologically impaired patient. For more in depth reading, the therapist is referred to the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) website (www.iasp-pain.org).

Types of pain

Nociceptive

This type of pain is physiological and arises as a consequence of the activation of nociceptors (pain receptors) following a chemical, thermal or mechanical event. The activation of primary nociceptive afferents by actual or potentially tissue-damaging stimuli is then processed within the nociceptive system (Treede et al. 2008). This type of pain may involve the musculoskeletal system but can also be from a visceral origin. It is important to note that not all nociceptive activation is perceived by the individual as ‘pain’. The perception of an unpleasant experience (pain) is highly subjective. Dystonic pain is associated with abnormal sustained muscle contraction (S3.18), which mediates the activation of nociceptive afferents in the muscles.

Psychogenic

This is pain that is caused, increased, or prolonged by cognitive, emotional, or behavioural factors. The IASP (2007) describe psychogenic pain as:

Neuropathic

This type of pain arises by activity generated within the nociceptive system without adequate stimulation of its peripheral sensory endings (nociceptors) and is caused by a primary lesion or dysfunction in the nervous system (IASP 2007). Some authors have further narrowed the dysfunction to a lesion of the somatosensory system (Treede et al. 2008). This includes the afferent neuron, the ascending and descending pathways, medulla, thalamus, or cerebral cortex. Therefore, neuropathic pain is sub-divided in relation to the anatomical site of the lesion (Dworkin et al. 2003).

Physiology of pain

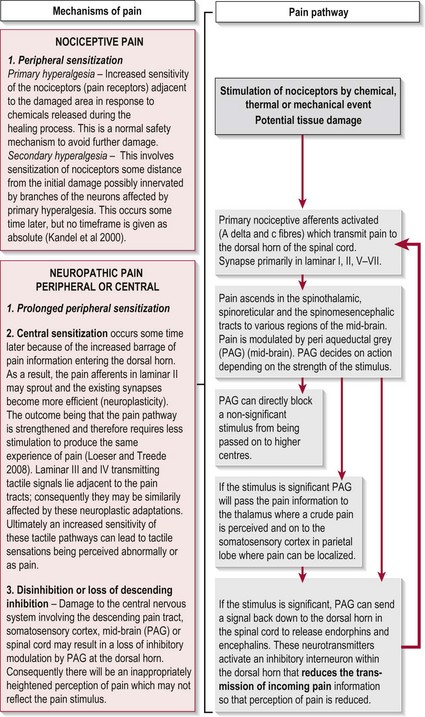

The experience of pain has a protective role which warns us of imminent or actual tissue damage and elicits responses, via signals within the nervous system, which keep such damage to a minimum. This brings about temporary pain hypersensitivity in the inflamed and adjacent tissue (peripheral sensitization). This process assists healing as contact and movement will be avoided. However, persistent pain offers no benefits and can be extremely debilitating. This maladaptive pain often occurs following damage to the peripheral nerve, the spinal cord or the CNS and is termed neuropathic pain (Woolfe and Mannion 1999). Figure 29.1 shows a simple flowchart outlining the normal pain pathway and the processes involved in pathological pain.

Figure 29.1 Pathophysiology of pain.

Symptoms associated with pain

Central neuropathic pain (CNP)

The symptoms of CNP occur as a result of CNS damage particularly to the somatosensory system which may lead to disinhibition and central sensitization (Fig. 29.1). With the pain pathway now inappropriately active, activity dependent neural plastic changes occur at the synapses within the whole pathway and may lead to an increase in the cortical representation (sensory homunculus) of the painful part. The timescales within which these neural changes take place and in which the symptoms develop is not clear with different studies stating from 1 month to 5–6 years.

The symptoms produced as a result of disinhibition and central sensitization include:

Allodynia

This is pain perceived following a non-noxious stimulus which does not normally provoke pain (e.g. touch, heat or non-noxious cold). This is common (90%) in central neuropathic pain (Widar et al. 2002).

Dysaesthesia

This is an unpleasant abnormal sensation. For example, burning, wetness, itching, electric shock, pins and needles. This is common in CNP (80%) (Attal et al. 2008).

Distribution of neuropathic pain

Peripheral neuropathic pain: In PNS lesions the pain distribution will conform to the cutaneous innervation of the peripheral nerve, the branches of the brachial or lumbar plexus, or spinal roots (dermatomes).

Central neuropathic pain: In CNS lesions the pain distribution will conform to the topographical representation of the brain area that has been injured by the lesion (i.e. the sensory homunculus). However, as central sensitization is one of the mechanisms that contributes to neuropathic pain, abnormal expansions of the sensory map should be expected.

Central neuropathic pain in neurologically impaired patients

Recent studies have also highlighted a further process that may contribute to CNP which involves the action of glial cells following a CNS lesion. In SCI and MS, inflammatory changes initiated in response to cell damage promote the release of inflammatory mediators and growth hormones by glial cells. If these chemical mediators affect the pain pathway, central sensitization may be enhanced (Svendsen et al. 2005). Although this has not been reported in CVA, it is likely that a similar mechanism takes place following the initial lesion and the resultant inflammatory response.

In PD the mechanism of CNP may be different. In healthy individuals the basal ganglia (S2.11) is now thought to play a significant role in the integration of sensory information and hence the modulation of pain (Juri et al. 2009). In PD the pathophysiology of pain has been linked to a disruption of the basal ganglia’s (striatum) ability to filter the vast amounts of sensory information in order to select an appropriate movement programme. This filtering is normally facilitated by the inhibitory dopaminergic neurons, however as the latter undergoes neurodegeneration in PD its effect is reduced. This may explain why pain may be relieved when in an ‘on’ period (i.e. taking L-Dopa).

Why do I need to assess pain?

While the available knowledge about pain, its physiology and pathophysiology has increased enormously over the last 20 years, it appears to have been largely ignored in respect to patients with neurological deficits. Pain in this population requires recognition as it has been shown to impact significantly on the patient’s quality of life and on the rehabilitative process (Henon 2006).

The incidence of pain in neurologically impaired patients is high, with reports of up to 74% in CVA and SCI; 50–85% in MS and between 40% and 75% in PD. A further breakdown of the different types of pain presented in these conditions can be seen in Tables 29.1–29.3

Table 29.1

Incidence of different types of pain in cerebrovascular accident

| Nociceptive pain | 5–84% |

| Shoulder pain | 30–40% |

| Chronic pain | 11–55% |

| Central neuropathic pain | 2–35% |

| Central post-stroke pain | 8–46% |

Widar et al. 2002; Jönsson et al. 2006; Lindgren et al. 2007; Kong and Woon 2004; Appelros 2006; Kumar and Soni 2009.

Table 29.2

Incidence of different types of pain in Parkinson’s disease

| Nociceptive pain | 40–70% |

| Non-dystonic | 37.8% |

| Dystonic | 6.7–40% |

| Peripheral neuropathic pain | 10% |

| Central neuropathic pain | 4.5–30% |

DeFazio and Tinazzi 2009; Beiske et al. 2009; Djaldetti et al. 2004.

Table 29.3

Incidence of different types of pain in multiple sclerosis

| Nociceptive pain | 21% (1% related to spasticity) |

| Peripheral neuropathic pain | 1% |

| Central neuropathic pain | 27.5% (87% in LL: 31% in UL) |

| Abnormal response to pain and temperature | 98% |

How do I assess pain?

Subjective assessment

Enquiry related to the following is required:

Behaviour of the symptoms

Severity of the pain (intensity). See visual analogue scale below.

Irritability of the pain, how long does it take for pain to reduce to previous level after a stimulus is removed?

Nature of the pain, a description of the symptoms of pain experienced.

Does the patient describe their pain using adjectives that are typically linked with physiological mechanisms? For example, a dull ache which is difficult to localize (muscle, ligament, joint capsule pain); morning pain that improves with activity (chronic inflammation/oedema); bizarre descriptions of pins and needles; wetness (central neuropathic pain); a sharp or burning pain or a line of pain (peripheral neuropathic pain).

Does the patient report a pattern of pain behaviour? The description of a typical pattern of pain behaviour may help identify a nociceptive origin. No pattern of pain behaviour may indicate a central neuropathic or psychogenic origin.

Does the patient report an irritable condition? The therapist will need to take care during the assessment and treatment not to aggravate their symptoms.

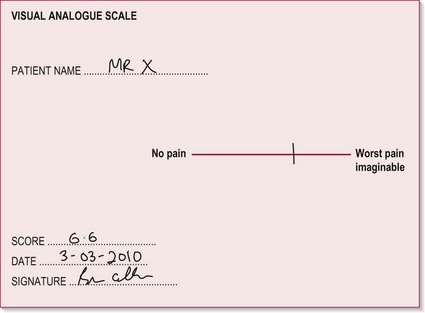

Visual analogue scale (VAS)

Therapist

1. The therapist draws a horizontal line on a piece of paper 10 cm long. The left hand end indicates a 0 score (no pain) and the right hand end a 10 score (the worst pain imaginable) (Fig. 29.2).

Figure 29.2 Visual analogue scale.

2. The patient is requested to rate their perceived pain intensity at that moment in time by making one mark on the line between the two extreme scores.

3. The therapist can then measure along the line from 0 to the point where the patient placed their mark. This value can be used as a quantitative marker for future evaluation.

The Neuropathic Pain Symptom Inventory (NPSI)

The Neuropathic Pain Symptom Inventory (NPSI) (Bouhassira et al. 2004) presents a broad overview of central neuropathic pain symptoms and may be useful to use as a reference source to assist the novice practitioner in identifying the signs of central neuropathic pain from the subjective assessment. Although it is often possible to diagnose neuropathic pain on the basis of history, a clinical examination is also essential (Treede et al. 2008).

Objective assessment

Observation

a. Muscle spasm guarding an area

b. Facial grimacing and either increased or decreased vocalizations during movement

d. Decreased range or altered patterns of movement

e. Altered muscle tone (S3.21)

g. Altered appetite and weight

h. Anxious and stressed. These factors may exacerbate pain

i. Fatigue/exhaustion. This may reflect a lack of sleep due to pain

j. Low mood and poor concentration. Depression may also exacerbate pain

Distribution of pain and other sensations

• Light touch testing (S3.23).

Does the patient exhibit an increased sensitivity to pain? This is hyperalgesia.

Does the patient exhibit a decreased sensitivity to pain? This is hypoalgesia.

Does the patient exhibit an abnormal pain response to a non-noxious stimulus? This is allodynia.

Does the patient report an unpleasant abnormal sensation? (e.g. burning, wetness, itching, electric shock, pins and needles). This is dysaesthesia.

Does the pattern of pain conform to the specific distribution of dermatomes or peripheral nerves? Yes. This is peripheral neuropathic pain. If not it is likely to reflect central neuropathic pain.

Differential diagnosis of nociceptive pain

If the patient’s pain is considered to be of nociceptive origin, a comparison of the findings from AROM (S3.23) and PROM (S3.23) and special clinical tests will allow the therapist to differentiate the structures implicated. In each case, the therapist is evaluating the reproduction of the patient’s pain in order to identify the source. Further comprehensive detail guiding differential diagnosis can be found from a range of musculoskeletal based texts.

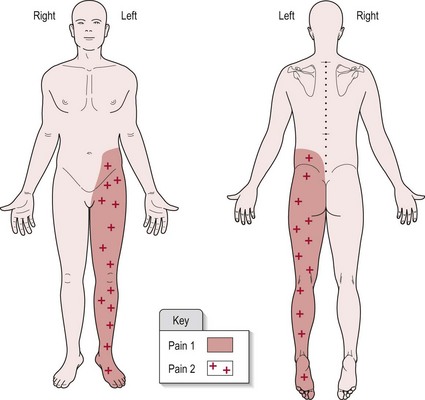

Recording

A separate section in your subjective write up should be headed ‘Pain’, with sub-headings as suggested in the above text. For the objective findings, a body chart showing the distribution of pain is a clear and easy way to present the information (Fig. 29.3). Use different symbols to highlight the various symptoms. The visual analogue scale (Fig. 29.2) should be included and the numeric result recorded in your notes.

Figure 29.3 Example of a body chart recording (pain).

Example

Patient diagnosed with CVA affecting the right parietal lobe (medially).

Onset of pain was 6/52 (6 weeks) post-CVA. Pain 1 is initiated by light touch and pain 2 relates to increased sensitivity to pin prick testing. Figure 29.3 shows the distribution of pain 1 and 2. There appears to be no discernible pattern to the pain behaviour. Pain is spontaneous and unaffected by movement or posture.

Analysis

For nociceptive pain, the therapist should also aim to identify the structure responsible for the nociceptive activation in order to focus treatment appropriately. This requires a reasoning process involving knowledge of anatomy, the possible mechanisms of injury related to different structures and the physiological processes involved in healing. For further guidance, the reader is referred to Grieve (2006). Remember that the source of pain may also be visceral in nature.

References and Further Reading

Appelros, P. Prevalence and predictors of pain and fatigue after stroke: a population-based study. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research. 2006; 29:329–333.

Attal, N, Fermanian, C, Fermanian, J, et al. Neuropathic pain: are there distinct subtypes depending on the aetiology or anatomical lesion? Pain. 2008; 138:343–353.

Beiske, AG, Loge, JH, Ronningen, A, et al. Pain in Parkinson’s disease: the hidden epidemic. Pain. 2009; 141:173–177.

Bouhassira, D, Attal, N, Fermanian, J, et al. Development and validation of the neuropathic pain symptom inventory. Pain. 2004; 108:248–257.

Day, R, Fox, J, Paul-Taylor, G. Neuro-musculoskeletal clinical tests: a clinician’s guide. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2009.

DeFazio, G, Tinazzi, M. Central pain and Parkinson’s disease. Archives of Neurology. 2009; 66:282–283.

Djaldetti, R, Shifrin, A, Rogowski, Z, et al. Quantitative measurement of pain sensation in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 2004; 62:2171–2175.

Dworkin, RH, Backonja, M, Rowbotham, MC, et al. Advances in neuropathic pain: diagnosis mechanisms and treatment recommendations. Archives of Neurology. 2003; 60:1524–1534.

Ehde, DM, Gibbons, LE, Chwastiak, L, et al. Chronic pain in a large community sample of persons with multiple sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis. 2003; 9:605–611.

Finnerup, NB. A review of central neuropathic pain states. Current Opinion in Anaesthesiology. 2008; 21:586–589.

Grieve, DJ. Orthopaedic physical assessment, ed 4. Canada: Saunders Elsevier; 2006.

Henon, H. Pain after stroke: a neglected issue. Journal of Neurology Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 2006; 77:569.

IASP, International Association for the Study of Pain wwwiasp-painorg/AM/Templatecfm?Section=Pain_DefinitionsandTemplate=/CM/HTMLDisplaycfmandContentID=1728, 2007

Jönsson, AC, Lindgren, I, Hallstrom, B, et al. Prevalence and intensity of pain after stroke: a population based study focusing on patients’ perspectives. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 2006; 77:590–595.

Juri, C, Rodriguez-Oroz, M, Obeso, JA. The pathophysiological basis of sensory disturbances in Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Neurologic Science. 2009; 289:60–65.

Kandel, ER, Schwartz, JH, Jessell, TM. Principles of neural science, ed 4. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2000.

Kong, KH, Woon, VC, Yang, SY. Prevalence of chronic pain and its impact on health-related quality of life in stroke survivors. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2004; 85:35–40.

Kumar, G, Soni, CR. Central post-stroke pain: Current evidence. Journal of Neurologic Science. 2009; 284:10–17.

Lindgren, I, Jönsson, AC, Norrving, B, et al. Shoulder pain after stroke: a prospective population-based study. Stroke. 2007; 38:343–348.

Loeser, JD, Treede, RD. The Kyoto protocol of IASP basic pain terminology. Pain. 2008; 137:473–477.

Osterberg, A, Boivie, J, Thuomas, K-A. Central pain in multiple sclerosis: prevalence and clinical characteristics. European Journal of Pain. 2005; 9:531–542.

Svendsen, KB, Jensen, TS, Hansen, HJ, et al. Sensory function and quality of life in patients with multiple sclerosis and pain. Pain. 2005; 114:473–481.

Treede, RD, Jensen, TS, Campbell, JN, et al. Neuropathic pain: redefinition and a grading system for clinical and research purposes. Neurology. 2008; 7018:1630–1635.

Widar, M, Samuelsson, L, Karlsson-Tivenius, S, et al. Long-term pain conditions after a stroke. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2002; 34:165–170.

Woolfe, CJ, Mannion, RJ. Neuropathic pain: aetiology, symptoms, mechanisms and management. The Lancet. 1999; 353:1959–1964.