67. Paget’s Disease of the Bone

Definition

Paget’s disease of the bone is a relatively common disease of middle-aged and elderly people in which there is excessive and abnormal bone remodeling. The condition results in extensively vascularized, weak, enlarged, deformed bones that are increasingly prone to subsequent complications.

Incidence

Determining the frequency of occurrence of Paget’s disease is inherently imprecise because many affected people are asymptomatic. The disease is estimated to affect approximately 3% of the population 40 years of age or older. Males are more commonly affected at a ratio of 1.8:1.

Etiology

The exact etiology of Paget’s disease remains unknown. Genetic and nongenetic contributions have been implicated, including factors related to viral infection, elevated parathyroid hormones, autoimmune deficiencies, connective tissue, and vascular disorders.

Signs and Symptoms

• Acetabulum protrusion

• Ataxia

• Back and neck pain

• Bone angulation and/or deformity

• Bone pain

• Bowel and bladder incontinence

• Cranial nerve palsies

• Dementia

• Dizziness

• Enlargement of skull and lower limbs

• Facial disfigurement

• Femur and long bone bowing

• Gait difficulties

• Hearing loss

• Limb paresis

• Malocclusion

• Muscle weakness

• Nausea

• Nonspecific headache

• Paresthesias

• Pathologic fractures

• Platybasia (also known as basilar impression: a developmental deformity of the occipital bone and upper end of the cervical spine in which the cervical spine appears to have pushed the floor of the occipital bone upward)

• Syncope

• Tibial or skull bruits

• Tinnitus

• Tooth loss

• Vertigo

|

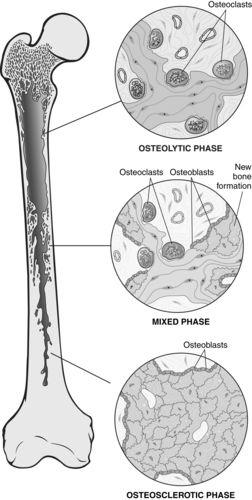

| Paget’s Disease of the Bone. Diagrammatic representation of Paget’s disease of bone, demonstrating the three phases in the evolution of the disease. |

Medical Management

Maintenance or improvement of muscle strength, maintaining joint range of motion and flexibility, increased endurance, and deconditioning avoidance are goals for initiation of physical therapy in the treatment of Paget’s disease. Superficial heat application, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, and massage are important physical therapy interventions that help reduce pain, tenderness, and tightness. Functional range-of-motion exercises are an integral incorporation to help maintain the function of major joints.

Occupational therapy is incorporated for the patient in need of training to “relearn” the performance of basic activities of daily life. Involving two occupational therapists in conjunction with physical therapy may strengthen the patient’s independence, safety, and mobility and can result in better maintenance or improvement of muscle strength.

Indications for Pharmacotherapy in the Patient with Paget’s Disease of the Bone

• Anticipated joint arthroplasty

• Bone pain

• Bony deformities

• Cardiac complications

• Hypercalcemia or hypercalciuria

• Neurologic complications

• Osteolytic lesions

• Prevention of future complications

• Serum alkaline or urine hydroxyproline more than twice the upper reference range

• Skull or spine disease

• Weight-bearing bone involvement

Complications

• Angioid streaks of the retina

• Autonomic hyperreflexia

• Calcific aortic stenosis

• Cranial nerve palsies

• Degenerative joint disease

• High-output cardiac failure

• Hydrocephalus

• Left ventricular hyper-trophy

• Pagetic sarcoma

• Pathologic fractures

• Platybasia

• Spastic quadriplegia

• Spinal cord compression

• Stress fractures

Anesthesia Implications

Securing the airway is always a concern for the anesthetist. That concern is increased for a patient with Paget’s disease of the bone. The characteristic bony fragility may be displayed in the patient’s facial bones, particularly the maxillae or mandible. Application of excess force during mask ventilation may produce significant injury. The patient with Paget’s disease is also prone to cervical instability and may become paraplegic with manipulation or head positioning for mask ventilation and/or intubation. The anesthetist must strive to maintain head neutrality throughout the process of direct laryngoscopy.

Positioning the patient requires more patience and indulgence than usual. Whenever feasible, the patient should be allowed or encouraged to position himself or herself to afford as much comfort as possible. Bony prominences and pressure points should be amply padded. Gel pads are preferable to foam padding because they disperse pressure more effectively while providing some measure of support.

Regional anesthesia may be appropriate, especially for total joint arthroplasty procedures. However, the spine should be examined radiographically to help the anesthetist avoid placing the needle into or through pathologic bone or injecting the local anesthetic into the same pathologic bone, which can result in a greater degree of toxic reaction.

The patient with Paget’s disease is frequently treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). The patient should be instructed to terminate the use of these drugs 10 days before elective surgery, but the anesthetist should evaluate the patient’s bleeding times and platelet function capabilities immediately preoperatively. The anesthetist should also be prepared for blood loss volumes in excess of the “usual and customary” for a given surgical procedure, particularly when the procedure involves the patient’s bones. In addition, the anesthetist should anticipate longer surgical/operative times when procedures involving instrumentation must be performed on sclerotic bone, which may also exacerbate the amount of blood loss the patient will incur. Massive blood transfusions should be anticipated and prepared for when the lower extremities are the surgical site.

The patient with kyphosis should have his or her pulmonary function evaluated before the day of surgery. The anesthetist and the patient should discuss the potential need for postoperative ventilatory support, particularly for a patient with significantly decreased pulmonary reserves and/or an airway that is difficult to secure.

If the patient has a spinal cord lesion, the anesthetist should be prepared to treat the sequelae associated with autonomic hyperreflexia (see p. 36). The anesthetist must be prepared to treat either hypotension or hypertension at a moment’s notice.