Chapter 30 Paediatrics

OVERVIEW OF PAEDIATRIC CONSIDERATIONS

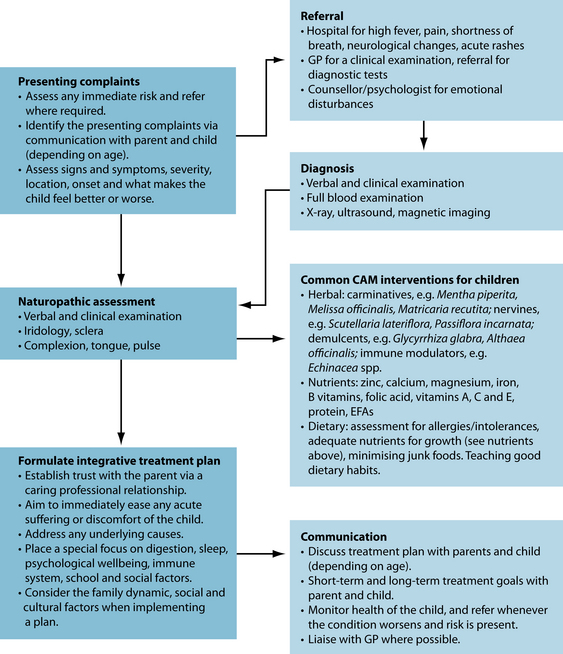

Working with children can be extremely rewarding, but it is very different from treating adults. Children often face very different medical conditions to adults and require specialised care. Practitioners need to be aware of children’s special needs, the sensitivity of the child, and the child’s parents and their siblings. While many childhood conditions can be treated in the family home, it is wise to seek the help of medical intervention when a condition is worsening, and to do so as soon as possible because children (especially babies) can become gravely ill quite quickly. Conversely, they can recover quickly once appropriate intervention is commenced. Children’s immune systems and nervous systems develop rapidly, and this also needs to be considered at all times when embarking on any health intervention.

The terminology for the classification of the paediatric patient is used in this chapter according to the definitions given at the International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH).1 The ICH recommended age should be classified in completed days, months or years following the stage categories of:

The United Nations’ Convention on the Rights of the Child defines a ‘minor’ as anyone under the age of 18 years.2

The use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in paediatric treatment is prevalent.3–5 Studies have shown that the use of one or more CAM therapies for treatment of children range between 20 and 70% of cases. The rates for general paediatric patients are 20–30%, for adolescents 30–70% and for paediatric patients with chronic or recurrent conditions, including those considered to be incurable, 30–70%.3,4 CAM practices used most commonly for children include infant massage, general massage and vitamin and herbal therapies. Demographic data for paediatric treatment reflect that seen in generalised populations, showing that the parents of children being given CAM therapies are often more educated and affluent. They choose to use CAM because they believe it is natural, lower cost, more effective, has been recommended by family or friends, are worried about possible side effects of conventional therapies, or conventional therapies have failed them in the past.3,4,6

Ethical and legal considerations

Cohen and Kemper raised some questions about the clinically appropriate use of CAM in paediatrics.5 They suggested that the non-judicious use of various CAM therapies may cause direct harm (or indirect harm) by creating an unwarranted financial and emotional burden. They recommended a series of questions that practitioners treating paediatric patients could ask when deciding how to advise patients on the use of CAM. These questions are:

Cohen and Kemper also concluded that paediatric use of CAM therapies may raise legal as well as clinical concerns.5 A cautious yet balanced approach ideally can help guide the specialised paediatric naturopath towards clinical advice (including referral) that is clinically responsible, ethically appropriate and legally defensible. Employing such an approach—one that embraces both clinical and legal concerns—can help to protect the child’s welfare as new parameters for integrative health care unfold.

PAEDIATRIC MEDICATION CONSIDERATIONS

The consensus is that children do not equate to small adults.7 There are marked differences in pathology, physiology, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics between children and adults.8–10 The efficacy of a medication depends on the practitioner selecting an appropriate preparation, calculating the correct dosage and motivating the family to ensure regular administration.11

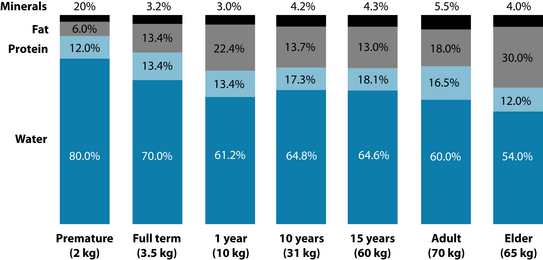

There are some important considerations when deciding the dose of medications at different life stages. Drugs are metabolised very differently in neonates and children compared to adults. Absorption is affected by differences in gastric acid secretion, bile salt formation, gastric emptying, intestinal motility and microflora.7 These are mostly reduced in a neonate and may also be reduced—though sometimes raised—in an ill child. The distribution of the volume of drugs in children can change with age because of the differences in the body’s composition of minerals, lipids, proteins and water (see Figure 30.1 below); plasma protein binding capacity also changes with age. Drug elimination can be longer in babies than adults. So, when medicating babies and children less than 12 years old, body weight and age should be considered.8 (See Table 30.1 with formulas below.)

| AGE | RULE | FORMULA |

|---|---|---|

| Birth to 12 months | Ausberger’s rule |  |

| 1–2 years | Fried’s rule (or Ausberger’s rule) |  |

| 2–12 years | Young’s rule or |  |

| Ausberger’s rule or |  |

|

| Clarke’s rule |  |

|

| 12–16 years | Ausberger’s rule |  |

| 16+ years | Unless the teenager is of small stature, adult doses may be considered. | |

Individual practitioners will have a preference for one formula over another when selecting a dose for children. Table 30.1 can be used to guide those in doubt when considering a herbal formula. Ausberger’s rule and Clarke’s rule for calculations of paediatric doses of medications are based on weight as opposed to age and may be more suitable to allow for the faster metabolism of children at certain ages.12 Fried’s rule and Young’s rule are based on age alone.

Hepatic metabolism

Medications are metabolised by enzymatic and metabolic reactions. Phase I activity for drug metabolism is reduced in neonates, increases progressively during the first 6 months of life, slows during adolescence, and usually attains adult rates by late puberty.8,9 Neonates metabolise medications much more slowly than adults do. By 6 months of age the immature reactions involving acetylation, glucuronidation and conjugation with amino acids have matured to adult levels.9 The metabolic pathways for phase II reactions reach adult levels by 3–4 years of age.9,14–16

Digestive flora

Colonisation of the gastrointestinal tract begins at birth and is usually established by week 1. The type of microorganism will depend on hygiene and diet. Bifidobacterium is the most prolific organism in a breastfed baby.13 It is estimated that the number of aerobic and anaerobic bacteria in newborns is up to a total of 1010/g wet weight.17 Implications of this altered flora are discussed in the chapters on irritable bowel syndrome, atopic skin disorders and asthma.

Nutrition in children

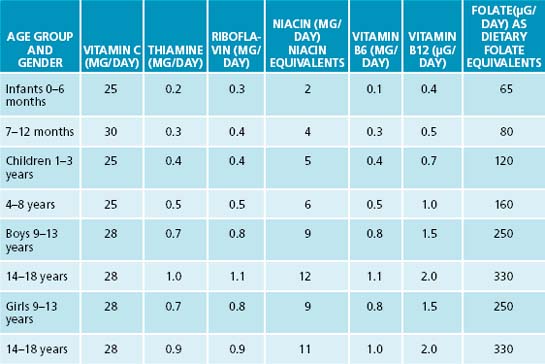

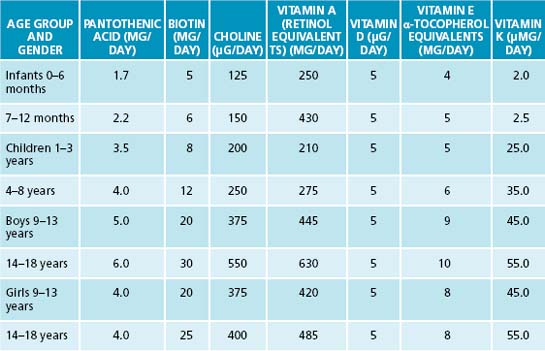

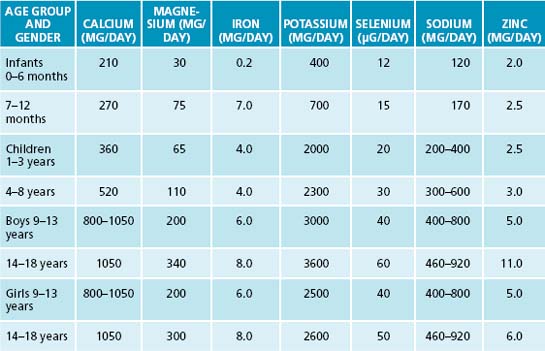

The physiological differences in children when compared to adults also result in differing nutritional requirements for children. This reflects the population’s unique needs for growth and development, as well as their differing maintenance requirements due to higher metabolisms. The estimated average requirements for the main nutrients are listed in Tables 30.2 and 30.3.18–20

Herbal medicine in children

The conditions encountered in paediatric practice may be different from those encountered in general practice (for example, otitis media and colic). Therefore the herbal medicines most commonly used will also differ. Table 30.4 outlines common paediatric conditions and herbal medicines used to treat these conditions.

Table 30.4 Commonly used herbs in paediatrics according to herbal tradition13,18,21–25

| MAIN CONDITIONS | MAIN TREATMENT ACTIONS | COMMON HERBS |

|---|---|---|

| Infants and toddlers | ||

| Colic | Carminative |

COMMON PAEDIATRIC CONDITIONS

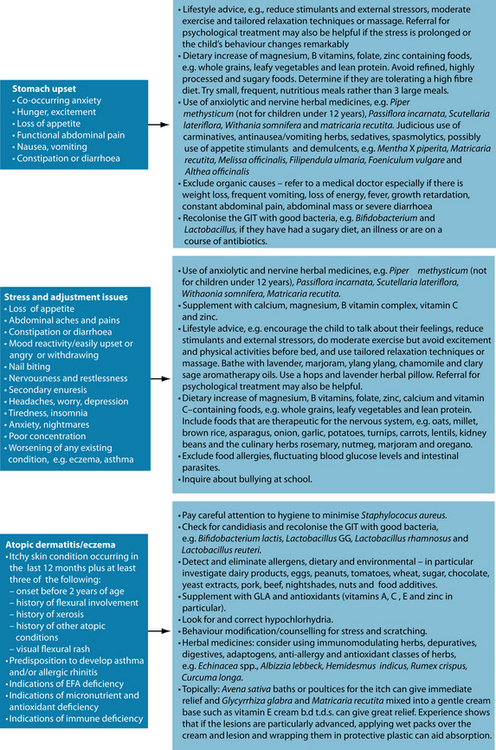

Generally, these conditions can be treated in a similar manner to the adult populations as suggested in appropriate chapters (while also paying attention to recommendations in this chapter). The more common conditions treated in infants and toddlers, children and adolescents are:13,25

COMPLIANCE ISSUES

Children

Children of all ages need to be given positive feedback on their progress and positive attitudes. Realistic goals should be set to increase the likelihood of compliance—for example, in the case of planned weight loss, planning to lose 1 of 10 kg by the next follow-up consultation if on a weight-loss plan, or having three different-coloured vegetables at least four times a week if diversifying their foods has been recommended.8

Adolescents

Older children and teenagers may rebel to assert their independence. They may feel that they need to be in control of their treatment and their illness, and they need to be involved and take responsibility for the progress of the illness and treatment.8 Open communications are to be encouraged; some rebellious behaviour is to be expected as adolescents learn to control their feelings and find their rightful place in their family and community.

Children and adolescents of all ages may resist treatment regimens that take them away from activities or classes or make them appear different to their friends. Engaging the adolescent appropriately in the treatment process may reduce these compliance issues.

Parents

An early follow-up telephone call can be made to see if the family has any residual questions and can assist with adherence to a new regimen.8 People under financial stress (a common occurrence when raising children) may have priorities other than paying for medicine. Ask the family to bring the medication bottles with them to each consultation and record the pill or liquid count or an estimation. Discrepancies could explain why expected results have not been achieved—many parents may simply not understand that under-dosing can reduce effectiveness. These considerations need to be taken into account when formulating a treatment plan.

Some parents may have beliefs or attitudes that deter or prevent them from giving children medications or other treatments.8 These considerations also need to be taken into account, and potential problems can be resolved by actively engaging the parents in the treatment process. Concise but informative and easily understandable oral and written instructions should be given to the parents for each suggested medication or other treatment. The instruction should explain what the medication or treatment is for, how it will work and any possible side effects that might occur.15

Classification, epidemiology and aetiology

Primary nocturnal enuresis (PNE) as defined by the International Continence Society30 is the involuntary discharge of urine at night in children aged 5 years or older who do not have congenital or acquired defects of the central nervous system or urinary tract and have not experienced a dry period of more than 6 months. Secondary nocturnal enuresis (SNE) is defined as for PNE except that these children have had a period of dryness of more than 6 months and enuresis has started again.30,31

PNE is a common childhood problem. Epidemiological studies in Western countries show a prevalence of 13–20% of 5-year-olds, 7% of 7-year-olds, 5% of 10-year-olds, 2–3% of 12–14-year-olds and 1–2% aged 15 years and older wet the bed on average twice a week at night.32,33 The prevalence of nocturnal enuresis (NE) decreases with age.34,35 Without treatment, about 15% of enuretic children will become dry each year.33,36

The aetiology can be multifactorial and can include genetic factors,33,37–39 physiological and psychological factors, a delay in the mechanism for bladder control maturation (antidiuretic hormone not increasing at night),40 a delay in maturation of the nervous system and impaired cortical arousal.38,39 Children with NE usually have normal bladder function and capacity but they can have a smaller nocturnal capacity.37,41 There can be other contributing factors such as a diet with large volumes of fluids before bed, caffeinated or diuretic drinks, constipation, sleep apnoea and upper airway obstructions and emotional stress.10,33,39 Constipation may result in bladder dysfunction. Urinary incontinence (46%) and NE (34%) has been reported in constipated children.42

Approximately 30% of all children with enuresis show clinically relevant behavioural disorders.42 PNE overall has a low comorbidity and externalising disorders predominate, whereas nocturnal SNE has a high comorbidity when both emotional (internalising) and externalising disorders occur.42

Risk factors

The key risk factor for a child with enuresis (both nocturnal and daytime) is the possibility of damage to the child’s self-esteem. These children can have low self-esteem, leading to a loss of confidence, poor school achievement and difficulty making friends.43 Bedwetters can be sad, embarrassed and ashamed and are fearful that their peers may find out their secret. These factors may prevent adherence to a treatment plan.42 Parents can feel anxious and guilty, and may lose confidence in their parenting skills and in the parent–child relationship.44 Bedwetting has been reported as the second-commonest reason for child abuse (second to persistent crying).45

The two commonly prescribed pharmaceutical medications need to be treated with caution. The antidiuretic drug Desmopressin, sometimes used for enuresis, has been associated with seizures and two deaths possibly due to hyponatraemia. Symptoms of hyponatraemia include nausea, vomiting, fatigue, muscle cramps and weakness.29 Imipramine, also used at times for enuresis, can have cardiotoxic side effects and death with overdose.42

Conventional treatment

Current medical treatments concentrate on alarm therapy (a behavioural modification therapy where the child is woken by an alarm immediately on bedwetting),31,37 pharmacological interventions (Desmopressin, oxybutynin, tolterodine and tricyclic antidepressants) and psychological interventions (such as counselling and psychotherapy—though there are no controlled trials),37,43 as well as other behavioural interventions such as reward systems and scheduled awakening.46

There are a wide variety of responses including cure, poor response, potential side effects and relapses after discontinuing the treatment.46–49 There is little high quality evidence for what is currently recommended for enuresis, but the majority of recommendations used by many health professionals are mentioned below.50

Enuresis alarm

This is the oldest specific therapy for enuresis. There are different types of alarm systems, but they all rely on the alarm alerting the child to void when the bladder is full.51

Key treatment protocols

The practitioner needs to convey a sense of compassion and understanding to the child and family.37 The parents and siblings need to be counselled that it is not appropriate to punish the child. Parental attitudes and experience should be taken into account in treatment plans as they can profoundly influence the outcomes.42

Treatment options

PNE and SNE are treated initially in the same way, and do not always require intensive treatment.37 The family needs to see a practitioner if the parent or child are frustrated by the bedwetting; the child is at least 6 years old; the parent or sibling punish or are worried that they may punish the child; or the child wets or has bowel motions in their pants during the daytime.35

Nutritional supplements

Nutritional supplements can be of use when deficiency states are present. There can be compliance issues when giving children nutritional supplements. Supplementation for children should be on the advice of a health-care practitioner trained in the area.52

Selenium may be of use in this case. Low dietary intakes of selenium have been linked with greater incidence of anxiety, depression and tiredness, whereas higher intakes and short-term selenium supplementation have been shown to elevate mood and anxiety in particular, under double-blind, crossover test conditions.18 In this case selenium 30 μg/day for 5 weeks for a 7-year-old (see Table 30.3) can be tried.

Herbal medicines

Most cases of nocturnal enuresis do not require medications, and this extends to herbal medicines.35 However, treatment with short-term herbal medication may help comorbid conditions such as the constipation and anxiety associated with this case. If they are causative factors, then herbal medicine could potentially be very important in resolving the condition.

There is a scarcity of evidence-based information about the commonly used herbal medicines for NE but traditionally the most commonly used herbs for monosymptomatic NE are Rhus aromatica,13 Piper methysticum,13 Plantago lanceolata,13 Hypericum perforatum,13 Viburnum opulus,13 Thuja occidentalis21 and Zea mays.13,21 Piper methysticum is not recommended by the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration for use by children under 12 years of age, and may be restricted in certain jurisdictions.13

In accordance with naturopathic principles any underlying causes need to be treated as quickly as possible. Constipation and anxiety are both potential causes for NE and may be treated with appropriate herbal medicines. Nervine tonic herbs that help lift the mood and are calming for anxiety and stress in children include Hypericum perforatum, Verbena officinalis, Melissa officinalis, Scutellaria lateriflora, Avena sativa, Turnera diffusa, Lavandula spp., Scutellaria baicalensis, Passiflora incarnata, Withania somnifera12 and Matricaria recutita. Appropriate herbs for constipation may include Iris versicolor, Turnera diffusa, Angelica polymorpha, Rumex crispus12 and Taraxacum officinale.21

Lifestyle

The use of alarms to alert the child and parents that enuresis is starting is the most successful form of treatment53 and effects a cure by itself in 80% of cases. A moisture-detecting mat placed on the bed is connected to a battery-powered alarm. Alarms can be used in combination with other forms of treatment. The child should be involved in the treatment and learn to turn the alarm on when they go to bed. When the child wets, the alarm sounds and the child should get up and go to the toilet to complete the micturition. It can take a couple of weeks to start having some dry nights. If the child is a deep sleeper, the parents may have to wake the child for the first few nights and take them to the toilet. The battery power is of low voltage and poses no danger to the child.35 Personal alarms that attach to the child’s clothing are also available.

In spite of NE the child should be encouraged to drink plenty of fluids during the day and extra when they are playing energetically or exercising. Diuretic and caffeine-containing fluids (such as tea, hot chocolate and colas) should be restricted in the evenings.35

Psychotherapy or counselling

If the parents are able to have the child discuss their concerns with them, it may not be necessary to seek professional counselling. However often the whole family is affected, and in this case parents, the affected child and any siblings may need counselling. If the child is sharing a room or a bed with siblings or parents this can exacerbate the stress on the family because of the disruptions in the middle of the night to change the bed linen and clean the child or others affected.54

It can be difficult to explain what stress is to a child, and the effect it can have on their body as well as their emotions and actions. Some of the subclinical psychological symptoms in children with NE are being unhappy, very unhappy, fitful, fearful, impatient, anxious and with feelings of inferiority.37 There are other responses such as the social consequence of not being able to stay at a friend’s house overnight, or have a friend stay; of affect being changed to feelings of sadness, shame or annoyance; of feeling isolated because they have a secret; and of the sensations of urine being unpleasant, cold, wet, itchy or nasty. A very small percentage of children reported the experience as an advantage such as liking the wet feeling or getting more attention from their mother.

When the child is ready to go to a friend’s for a sleepover, discuss the situation with the other child’s parent, and hide a pull-up nappy in the bag for the child to discreetly put on so that the child need not be embarrassed.45

Meditation may also be an effective tool for managing stress, and children benefit as much as adults.55 There are many effective meditations for children and practising the meditations with the family can be a way of having family interactions that give health benefits and family cohesion.

Dietary considerations

In the case of a poor appetite, encourage small meals frequently rather than three larger meals a day, and encourage nutrient-dense foods. Foods rich in magnesium, calcium, zinc and essential fatty acids are of benefit to growing children and magnesium-rich foods are indicated for anxiety states where magnesium may be deficient.18

Food sensitivities should also be considered. One study of 21 children with migraine and/or hyperkinetic behaviour and NE that were placed on a restricted ‘oligoantigenic’ diet found significant remission of NE.56 Twelve of the 21 had remission of their NE when on the diet. Nine of the responders were then challenged with reactive foods and later with non-reactive foods. Six children given reactive foods did have a return of their NE but none of the nine responded with NE when given non-reactive foods. Although the study provides tentative support for this dietary modification, it is worth consideration if food intolerances or allergies are suspected. Given the large numbers of children with NE, there is a need for more research in this area.

Integrative medical considerations

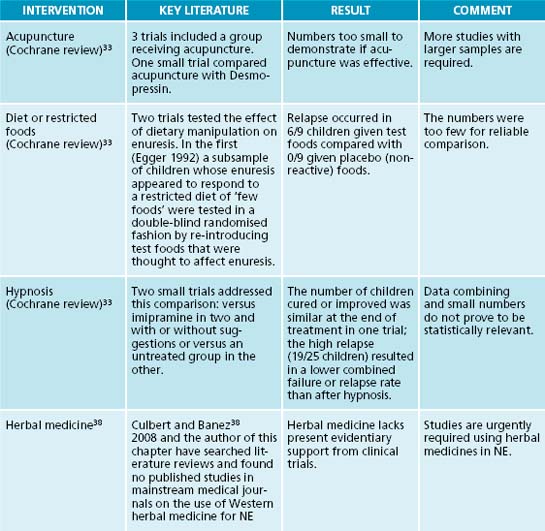

Hypnotherapy

Children generally are receptive to hypnosis, make good subjects for guided imagery and can have good results for a lot of conditions, including NE. Culbert et al.38 reported four classic studies where hypnosis had better outcomes for bladder control than other treatments including pharmaceuticals, especially in the long term after cessation of treatments. Teaching children self-hypnosis is empowering for the child as they can take control of their own conditions.

Homoeopathy

There does not appear to be any published studies on the effects of homoeopathy and NE.38 Homoeopathic texts list several remedies which when matched appropriately to the symptom picture may effect a cure: Cina 30, Causticum 200, Sepia Officinalis 200, Equisetum Hyemale 30, Verbascum Thapsus 30, Kreosotum 30 and Calcarea Carbonica 200.57

Acupuncture

Laser acupuncture may be a more gentle approach than needling when treating children. The literature published on acupuncture’s effectiveness for treating NE is conflicting. Bower et al.58 published a systematic review of acupuncture for paediatric NE. They evaluated 206 abstracts. Eleven were deemed eligible for data abstraction. The authors reported tentative evidence for the efficacy of the treatments, although they comment that the studies were of poor methodological quality.

Example treatment

Nutritional prescription

Herbal formula

| Turnera diffusa 1:2 | 30 mL |

| Hypericum perforatum 1:2 | 40 mL |

| Glycyrrhiza glabra 1:1 | 30 mL |

| 100 mL | |

| Dose (Young’s rule) 2 mL t.d.s. a.c. | |

| Chamomile tea b.d. p.c. | |

Turnera diffusa acts as a nervine tonic, tonic and mild laxative. Its potential indications include nervous dyspepsia, constipation, nervousness, anxiety and depression.12 There is no specific safety information available for its use in paediatrics, but it is used as a slimming tea in Mexico served to children.13 Hypericum perforatum is prescribed for its nervine properties. Several human studies confirm the mood-modulating effect of St John’s wort extract (see Section 4 on the nervous system) and it is well tolerated by children (there were no adverse effects in one trial with 101 children13). Matricaria recutita is sedative, calming on the stomach and improves

mood.18 It is considered safe when taken by children.13 Glycyrrhiza glabra has a mild laxative effect, acts as an adrenal tonic and has a sweet flavour. Care should be taken that the child is not consuming the confectionery liquorice concomitantly so that excessive exposure is avoided.13

Additional prescriptive options

The diet may be improved more generally by encouraging a wide variety of colours and textures in foods with daily selections of vegetables, fruits, nuts and seeds to educate the children to good lifelong eating patterns. If this is coupled with appropriate physical activity, fun, laughter, love and respect, it may help the child recover. Rich selenium sources such as brewer’s yeast, wheat germ, meats, fish, seafood, brazil nuts and garlic may also be useful as low dietary intakes of selenium have been linked with depression and anxiety.18 Abdominal massage with a relaxing oil such as lavender after drinking a warm drink has been traditionally used to help relieve constipation. The gentle strokes must go up the ascending colon, across the transverse colon and down the descending colon. Chickweed is a nutritious food and traditional herbal medicine uses it to help with constipation. It should be avoided at night as it can have a mild diuretic effect.18

Therapeutic considerations

If the child is staying overnight at a friend or relative’s house, discreetly add a pull-up nappy so the child can put it on privately. NE can lead to frictions in a family with tired, frustrated, worried parents. Children with the condition need lots of bedclothes, and an increase in washing added to an already busy routine can cause extra strain on the family and parents. Staying in nappies is unlikely to help the problem. It can cut down on washing, but the child has no incentive to wake up when the bladder is full. Neither will nappies work with alarms.35 Ensure the parents understand and agree with the diagnosis, see it as serious, and believe that the treatment will eventually work. For some, this may involve directing them to research findings and connecting them with relevant institutions such as the Bedwetting Institute (http://www.bedwettinginstitute.com.au).

Expected outcomes and follow-up protocols

The best outcomes come from the child, parents and practitioner working together.34 If there is compliance with herbs, diet and alarm, resolution may be expected within a few months.

NE is a significant problem from the perspective of both the child and their parents. Understanding their perceptions will help in formulating a successful treatment plan.54 Giving positive reinforcement without being negative on the ‘wet’ days will assist the recovery and help the child raise their self-esteem. Aiming for achievable goals will lessen frustrations.59

Frequent follow-ups are important—with emotional support for both the parents and the child.60

The child needs to be very involved in their treatment if it is to work. It is important to recognise that there will be good and bad days. Have the child make a diary or chart to record the dry nights and encourage them to decide how it should be completed.35

Surprises are a good idea when they are making progress but it is not advisable to promise big rewards (like a new puppy or bicycle) because it may add to the stress, particularly if they do not succeed in staying dry.35 The parents too sometimes need rewards during this process so suggest they plan to have a few nights alone.

It may be reasonably expected that this case of SNE will resolve quickly in a supportive familial environment. If the stress is managed and controlled, the child could be ‘dry’ every night in 2–3 months. Once this has occurred there is no need to continue the herbal and supplement treatment, but the dietary suggestions should continue. Other ‘non-clinical’ factors such as making new friends at the new school should help with the child’s distress and treatment success.

KEY POINTS

Garth M. Starbright meditations for children. North Blackburn: Collins Dove; 1992.

Garth M. Moonbeam meditations for children. North Blackburn: Collins Dove; 1993.

Glazener C., Evans J., Cheuk D. Complementary and miscellaneous interventions for nocturnal enuresis in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2):2005. CD005230

Robson W..Clinical practice. Evaluation and management of enuresis. N Engl J Med. 2009;36014:1429-1436.

Santich R., Bone K. Phytotherapy essentials: healthy children: optimising children’s health with herbs. Warwick: Phytotherapy Press; 2008.

United Nations. Conventions on the rights of the child. General Assembly resolution 44/25 of 20 November 1989. Geneva, Switzerland. Online. Available: http://www.unicef.org/crc. 1989

http://www.bedwettinginstitute.com.au

PO Box 737 Glebe 2037 NSW Australia

International + 61 2 9518 8769

International Fax: + 61 2 82 105 125

The Continence Foundation of Australia

The National Continence Management Strategy

http://www.bladderbowel.gov.au/ncms/

The International Children’s Continence Society

1. International Conference on Harmonisation. Clinical investigation of medicinal products in the paediatric population E11. Online. Available: http://emea.europa. eu/htms/human/ich/ichefficacy.htm.

2. United Nations. Conventions on the rights of the child. General Assembly resolution 44/25 of 20 November 1989. Geneva, Switzerland. Online. Available: http://www.unicef.org/crc.

3. Kemper K. Complementary and alternative medicine for children: does it work? Archives of Disease in Children. 2001;84:6-9.

4. Loman D. The use of complementary and alternative health care practices amoung children. J of Paediatric Health Care. 2003;17:58-63.

5. Cohen M., Kemper K. Complementary therapies in paediatrics: a legal perspective. Paediatrics. 2005;115(3):774-780.

6. Tillisch K. Complementary and alternative medicine for functional gastrointestinal disorders. GUT. 2006;55:593-596.

7. Ethics Advisory Committee.Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health. Guidelines for the ethical conduct of medical research involving children. Arch Dis Ch. 2002;82(2):177-182.

8. Beers M.H., et al, editors. Merck manual of diagnosis and therapy. Whitehouse Station: Merck Research Laboratories, 2006.

9. Suggs D. Pharmacokinetics in children: history, considerations, and applications. J of the American Academy of Nursing. 2000;12(6):236-239.

10. Kurtz R., Gill D. Practical and ethical issues in pediatric clinical trials. Applied Clinical Trials. 2003. September, article 79923. Online. Available: http://appliedclinicaltrialsonlinefindpharma.com/appliedclinicaltrials/author/authorDetail jsp?id+5124

11. Hull D., Johnston D.I., editors. Essential paediatrics, 3rd edn, Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1993.

12. Bone K. A clinical guide to blending liquid herbs. Herbal formulations for the individual patient. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2003.

13. Santich R., Bone K. Phytotherapy essentials: healthy children:optimising children’s health with herbs. Warwick: Phytotherapy Press; 2008.

14. Zenk K. Challenges in providing pharmaceutical care for pediatric patients. American Journal of Hospital Pharmacy. 1994;51:683-694.

15. Reed M. Principles of drug therapy. In Nelson W.E., Behrman R.E., et al, editors: Textbook of pediatrics, 15th edn, W.B. Saunders Co, 1996.

16. Niederhauser V. Prescribing for children: Issues in pediatric pharmacology. American Journal of Primary Health Care. 1997;22(3):16-30.

17. Millard R., et al. Clinical efficacy and safety of tolterodine compared to placebo in detrusor overactivity. Journal of Urology. 1999;161:1551-1555.

18. Braun L., Cohen M..Herbs and natural supplements. An evidence-based guide. Sydney: Elsevier Australia; 2007.

19. NHMRC. Nutrient reference values for Australia and New Zealand including recommended dietary intakes. Australian Federal Government. 2006.

20. Shils M., et al, editors. Modern nutrition in health and disease, 10th edn, Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2006.

21. Thomsen M. Phytotherapy desk reference, 2nd edn. Denmark: Michael Thomsen Publishing; 2005.

22. Mills S., Bone K. Principles and practice of phytotherapy. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2000.

23. Brewin L. Natural health for children. In An A–Z of childhood ailments and how to treat them naturally. Australian Broadcasting Corporation; 2002.

24. Pizzorno J., et al. The textbook of natural medicine. Churchill Livingstone; 2008.

25. Scott J., Barlow T. Herbs in the treatment of children. Missouri: Churchill Livingstone; 2003.

26. Sarrell E., et al. Naturopathic treatment for ear pain in children. Pediatrics. 2003;111(5):574-579.

27. Hyman P., Danda C. Understanding and treating childhood bellyaches. Pediatr Annals. 2004;33(2):97-104.

28. Williams H. Epidemiology of atopic dermatitis. Clinical Exp Dermatol. 2000;25(7):522-529.

29. Online. Available: http://www.medicinnet.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=85646

30. Norgarrd J.P., et al. A standardization and definitions in lower urinary tract dysfunction in children. Br J Urol. 1998;81(1):1-16. (Supplement 3)

31. Robson W. Clinical practice. Evaluation and management of enuresis. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1429-1436.

32. Nijman R.J.M., et al. Committee 10A. Conservative management of urinary incontinence in childhood. In: Abrams P., Cardozo L., Khoury S., Wein A., editors. Incontinence, in Proceedings of the Second International Consultation on Incontinence. Health Productions Ltd; 2002:513-551.

33. Glazener C.M.A., et al. Complementary and miscellaneous interventions for nocturnal enuresis in children. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (2):2002. CD005230

34. Gumus B., et al. Prevalence of nocturnal enuresis and accompanying factors in children aged 7–11 years in Turkey. Acta Paediatr. 1999;88:1369-1372.

35. Rural children’s Hospital (melbarne). Bedwetting. Online. Available: http://www.rch.org.au/kidsinfo/factsheets.cfm?doc_id=3716

36. Freehan M., McGee R., Stanton W., Silva P.A. A 6-year follow-up of childhood enuresis: prevalence in adolescence and consequences for mental health. J Paediatric Child Health. 1990;26:75-79.

37. Hjalmas K., et al. Nocturnal enuresis: an international evidence based management strategy. Journal of Urology. 2004;171(6 II):2545-2561.

38. Culbert T., Banez G.A. Wetting the bed: integrative approaches to nocturnal enuresis. Journal of Science and Healing. 2008;4(3):215-220.

39. Caldwell P.H.Y., Ng C..Management of childhood enuresis. [online]. Med Today. 2008;8:16-20, 22–24.

40. Sobenin I.A., et al. [Reduction of cardiovascular risk in primary prophylaxy of coronary heart disease]. Klin Med (Mosk). 2005;83(4):52-55.

41. Sheldon S. Sleep-related enuresis. In: Sheldon S., et al, editors. Principles and practice of pediatric sleep medicine. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders, 2005.

42. Hjalmas K., et al. Nocturnal enuresis: an international evidence based management strategy. Journal of Urology. 2004;171(6, Part 2 of 2):2545-2561. 2004

43. Blackwell C. A guide to the treatment of enuresis for professionals. Bristol: Enuresis Resource and Information Centre; 1989.

44. Hagglof B., et al.Self esteem before and after treatment in children with nocturnal enuresis and urinary incontinence. Scand J Urol Nephrol Suppl. 1997(183):79-82.

45. Dobson P. Enuresis. Bedwetting—the last taboo. Nurs Stand. 1990;4:25-27.

46. Glazner C.M.A., Evans J.H.C. Desmopressin for nocturnal enuresis in children. Cochrane Database System Review. (3):2002. CD 002238

47. Glazner C.M.A., Evans J.H.C..Tricyclic and related drugs for nocturnal enuresis in children. Cochrane Database System Review. 2003(3):CD002117.

48. Glazner C.M.A., Evans J.H.C..Drugs for nocturnal enuresis in children (other than desmopressin and tricyclics). Cochrane Database System Review. 2003(4):CD002238.

49. Glazner C.M.A., et al.Complex behaviour and educational interventions for nocturnal enuresis in children. Cochrane Database System Review. 2004(1):CD004668.

50. Wicks G.R. Bedwetting and toileting problems in children/In reply. Medical Journal of Australia. 2005;182(11):596.

51. Wright A. Evidence-based assessment and management of childhood enuresis. Paediatrics and Child Health. 2008;18(12):561-567.

52. Mansberg G..Paediatric complementary medicine. J Complementary Medicine. 2004(March/April):37-40.

53. Glazner C.M.A..Alarm interventions for nocturnal enuresis in children. Cochrane Database System Review. 2005(2):CD002911.

54. Ng C.F.N., Wong S.N. Primary nocturnal enuresis: patient attitudes and parental perceptions. HK J Paediatrics. 2004;9(1):54-58.

55. Ott M. Mindfulness meditation in pediatric clinical practice. Pediatr Nurs. 2002;28(5):487-490.

56. Egger J. Effect of diet treatment on enuresis in children with migraine or hyperkinetic behaviour. Clin Pediatrics. 1992;31:302-307.

57. Allen H. Keynotes: rearranged and classified with leading remedies of the materia medica and bowel nosodes. Delhi: B. Jain Publishers; 1999.

58. Bower W.F., et al. Acupuncture for nocturnal enuresis in children. A systematic review and exploration of rationale. Neurourol Urodyn. 2005;24:267-272.

59. Berry A. Helping children with nocturnal enuresis. AJN. 2006;106(8):58-65.

60. Longstaffe M.M., Whelan J.C. Behavioural and self concept changes after six months of enuresis treatment: a randomised, controlled trial. Paediatrics. 2000;105(4 pt 2):935-940.