22 Paediatric, teenage and young adult cancers

Introduction

In addition they have particular social, educational, developmental and psychological needs which, if not addressed, have long-term consequences for the patient and their family. Those who survive cancer at a young age may also be left with significant medical late effects which need to be recognized and managed (p. 58).

Incidence/epidemiology

The incidence of malignancy in the UK is:

Cancer is the most frequent natural cause of death in this age group, second only to accidents.

Types of cancer

The types of cancer vary not only between children and adults but as the age increases in certain age group bandings (Table 22.1).

| Age 0–14 years | Age 15–19 years | Age 20–24 years |

|---|---|---|

Clinical features

In children warning signs may be due to localized disease, or the manifestations of disseminated disease are listed in Box 22.1.

Diagnosis and delays

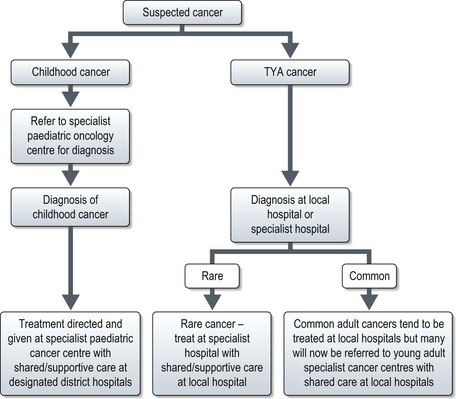

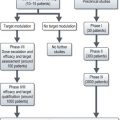

Diagnosis of malignancy currently follows the pathways for either paediatric or adult cancers. Paediatric cancers are diagnosed and treated in specialist principal treatment centres with some care shared with local hospitals. For TYA cancers, currently they may be seen in a paediatric or adult setting and treated according to those protocols. In the UK TYA cancer will soon be treated in specialized centres. This may mean referral to a specialist TYA centre or to an adult cancer specialist in a particular site of the body in a designated regional hospital with appropriate TYA facilities (Figure 22.1).

Specific childhood cancers

Leukaemias

In childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) is by far the most frequently occurring leukaemia representing over 75% cases. (p. 308).

Presentation is usually with symptoms and signs of bone marrow infiltration and these can appear to occur quite rapidly, although are often preceded by several weeks of general malaise or recurrent infections and fevers. Usual features at the time of diagnosis are pallor, abnormal bruising or bleeding, bone pain (which may manifest as limping in young children) and on clinical examination lymphadenopathy and hepatomegaly in some children.

Diagnosis is suspected on the differential blood count but bone marrow examination is essential to confirm the diagnosis (p. 308), to perform immunocytochemical stains and cytogenetics which are of diagnostic and prognostic significance (Box 22.2).

Treatment of childhood and young adult ALL is performed according to risk stratification as in Box 22.2. In general treatment involves several phases which is similar to that of adult ALL (p. 308).

Relapsed ALL may still be curable with high-dose chemotherapy and stem cell transplantation, but the chances of long-term cure are much lower with the high-risk subgroups and if relapse is within a year of completing initial treatment.

In addition certain subgroups such as B-cell ALL are often treated on different regimens similar to those used for a Burkitt’s lymphoma (p. 305, Burkitt’s lymphoma). Both these malignancies are associated with a t(8;14) translocation so may be variations of the same malignancy.

Brain tumours

Common subtypes of brain tumour include astrocytoma, medulloblastoma, glioma, craniopharyngioma and ependymoma. In children, particularly in the very young, the emphasis of treatment is to delay, avoid or minimize the need for radiotherapy to avoid long-term side effects. These are covered in more detail on p. 264.

Wilms’ tumour

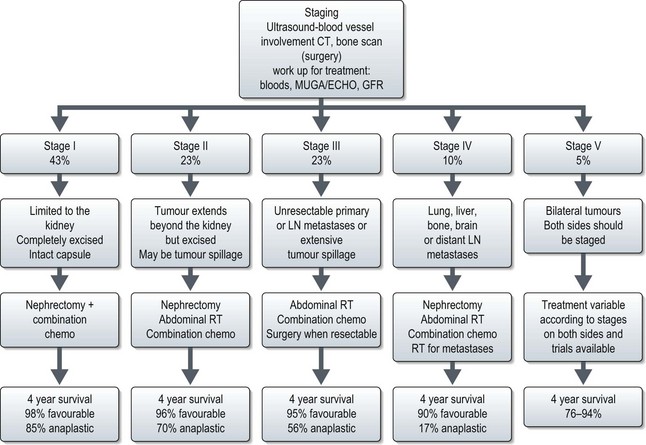

Staging is undertaken with imaging and treatment is according to stage (Figure 22.2). Anaplastic tumours are treated with more aggressive chemotherapy except in stage I where their prognosis is similar to favourable histology tumours. Overall more than 80% are cured of their disease. Treatment for relapse is rarely curative.

Neuroblastoma

Poor prognostic features are advanced stage, age over 1 year, and over-expression of N-myc oncogene.

Lymphomas

Lymphomas occur in childhood and Hodgkin’s disease has a peak in incidence in young adulthood (p. 298). In general these tumours are treated similar to their adult counterparts except that radiotherapy is avoided, except in refractory disease, to reduce the risk of its effect on growth and the risk of second malignancy. Chemotherapy regimens are similar to adults but trials are ongoing to assess the role of rituximab in children. The most common subtypes of NHL in children are Burkitt-like lymphomas (p. 305) and diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (Table 22.2). Anaplastic large cell tumours are rare as are other adult subtypes such as cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and MALT lymphoma (p. 306). Prognostic factors are similar to adult tumours.

Table 22.2 Major histopathological categories of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in children and adolescents

| Category (WHO Classification/updated REAL) | Immuno-phenotype | Clinical presentation |

|---|---|---|

| Burkitt and Burkitt-like lymphomas | Mature B cell | Intra-abdominal (sporadic), head and neck (non-jaw, sporadic), jaw (endemic) |

| Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma | Mature B cell; may be CD30+ | Nodal, abdomen, bone, primary CNS, mediastinal |

| Lymphoblastic lymphoma, precursor T-cell/leukaemia, or precursor B-cell lymphoma | Pre-T cell | Mediastinal, bone marrow |

| Pre-B cell | Skin, bone | |

| Anaplastic large cell lymphoma, systemic | CD30+ (Ki-1+) | Variable, but systemic symptoms often prominent |

| T cell or null cell | ||

| Anaplastic large cell lymphoma, cutaneous | CD30+ (Ki-1+usually) | Skin only; single or multiple lesions |

| T cell |

Sarcomas

Both bone and soft tissue sarcomas occur in children and young adults. These are covered in detail in Chapter 15. Some sarcomas, however, peak in this age group. Osteosarcomas peak in early adolescence with Ewing’s sarcomas having their peak incidence in older adolescence. Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS), a tumour of striated muscle, is the only soft tissue sarcoma to peak in children and adolescents. It is divided into two main histological subgroups, embryonal and alveolar. Alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma (ARMS) is characterized by one of two specific translocations, either t(2;13)(q35;q14) resulting in fusion of PAX3-FOXO1 in 60% ARMS or t(1;13)(q36;q14) resulting in PAX7-FOXO1 in 20% ARMS. Embryonal RMS is not associated with a specific translocation, but loss in chromosome 11. Common tumour sites include the head and neck, paratesticular and limb (Figure 22.3). It frequently presents with advanced disease. If localized it can present with a mass or proptosis if retro-orbital. It can give rise to nodal metastases and regional lymph nodes should be examined. Staging involves local MRI, CT of chest (and regional), bone scan, and bone marrow biopsy. Localized disease is treated with surgery, but due to the aggressive nature of these tumours, combination chemotherapy with e.g. IVADo (ifosfamide, vincristine, actinomycin and doxorubicin), is given. Radiotherapy is often given if margins are positive or there has been tumour regrowth after initial surgery. An Italian pilot study suggested that maintenance therapy with cyclophosphamide and vinorelbine may prolong progression free survival. In advanced disease combination chemotherapy is used but the outlook is poor. Poor prognostic factors include increasing age, particularly over age 16, advanced stage and alveolar subtype.

Germ cell tumours

Germ cell tumours of the ovary and testes peak in young adulthood and are described in more detail in Chapters 12 and 13. Similar treatment modalities are used in children and young adults, but there has been a move to reduce long-term side effects from chemotherapy and to try to maintain fertility in ovarian germ cell tumours. Trials are underway to examine the role of carboplatin rather than cisplatin and to reduce the dose of bleomycin in adolescent germ cell tumours to reduce late effects. Fertility sparing surgery is preferred if possible for ovarian germ cell tumours and many women retain their fertility with this type of surgery and BEP chemotherapy (p. 220).

Hepatoblastomas

Hepatoblastomas are rare but are most common malignancy of liver in children. There is an association with FAP. Hepatocellular carcinoma can also occur rarely but in older age groups. Clinical presentation is usually with a mass or abdominal distension. Jaundice is rare. Alpha-foetoprotein (AFP) is elevated in most cases. Unlike adult liver tumours, most hepatoblastomas respond to combination chemotherapy (cisplatin and doxorubicin) with good long-term survival.

Retinoblastoma

Retinoblastomas are very rare childhood tumours. All bilateral tumours and 20% of unilateral tumours are thought to be hereditary. The retinoblastoma tumour suppressor gene is on chromosome 13 with the pattern of inheritance being autosomal dominant with incomplete penetrance (Chapter 5, p. 55). Most cases present before age 3. In children not known to be in a retinoblastoma family presentation is with a squint or white papillary reflex. Those related to retinoblastoma families should be part of a screening programme. Surgery may be necessary for some but most cases are treated with radiotherapy. Long-term survival is over 95%, but second malignancy is common (osteosarcomas in radiotherapy field) and in those with hereditary retinoblastoma other malignancies, especially sarcomas can occur elsewhere in the body in young adulthood up to middle age.

Body image and fertility

Sexual identity and future fertility are important considerations for the adolescent or young adult. Loss of hair or a limb will significantly affect body image at an age when this is especially vulnerable. The type of cancer or its treatment may also affect future fertility, but this is not universal so specific knowledge is required for each patient (p. 59, late effects).

Late effects

Late effects are an important factor in the treatment of children and young adults (p. 58, late effects). Late effects are dependent upon the original cancer, its treatment, the family genetics and the developmental stage of the individual when treated for cancer. Every organ system can be affected, but the most significant include the risk of second malignancy, neurocognitive impairment, growth problems, and cardiac and endocrine abnormalities. Many centres run late effects clinics to monitor for these and other sequelae of cancer treatment.

Albritton K, Bleyer WA. The management of cancer in the older adolescent. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:2584-2599.

Birch JM, Alston R, Quinn M, Kelsey A. Incidence of malignant disease by morphological type in young persons aged 12–24 years in England, 1979–1997. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:2622-2631.

Martin S, Ulrich C, Munsell M, et al. Delays in cancer diagnosis in underinsured young adults and older adolescents. The Oncologist. 2007;12:816-824.

Ramanujachar R, Richards S, Hann I, et al. Adolescents with ALL: outcome on UK national paediatric and adult trials. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48:254-261.

2005 Guidance on Cancer Services – Improving outcomes in children and young people with cancer. August. Available from www.nice.org.uk, 2005.