17 Paediatric surgery

General principles of paediatric surgery

Priorities in care for an infant being transferred to a regional centre include:

Table 17.1 Maintenance fluid requirements in the first week of life

| Day | Fluid (mL/kg/24 h) |

|---|---|

| 1, 2 | 60 |

| 3, 4 | 90 |

| 5, 6 | 120 |

| >7 | 150 |

Respiratory distress

Oesophageal atresia and tracheo-oesophageal fistula

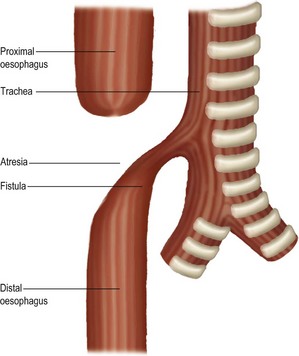

One in 4000 babies has an oesophageal anomaly, most usually a mid-oesophageal atresia with a distal tracheo-oesophageal fistula (Fig. 17.1). Half the infants with oesophageal abnormalities have associated problems, including cardiovascular, renal and skeletal defects.

Upper airway obstruction

• cystic hygroma: a fluid-filled collection in the neck which may extend to the mediastinum or axilla

• a small jaw (micrognathia), where a hypoplastic mandible causes obstruction of the pharynx by prolapse of the tongue associated with cleft palate. This is the Pierre Robin syndrome

• choanal atresia: a bony membranous obstruction to the nasal passages at the junction of the hard and soft palates. This diagnosis is confirmed by the inability to pass a nasal tube into the pharynx.

Neonatal intestinal obstruction

General clinical features of neonatal intestinal obstruction

The history includes details of maternal illness, for example diabetes mellitus, and medication during pregnancy. A history of intestinal obstruction, Hirschsprung’s disease or cystic fibrosis in relatives may be relevant. There is bile-stained vomiting (Box 17.1), failure to pass meconium or stools that change to the characteristic neonatal output, and abdominal distension.

Abdominal wall defects

The most common abnormalities of the abdominal wall, which are all rare, include:

Exomphalos

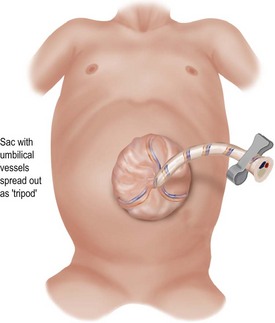

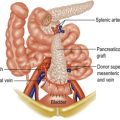

This is a defect with the umbilical cord inserted into a transparent amniotic sac with the vessels spreading out (Fig. 17.2). The sac contains loops of bowel and sometimes liver. There may be associated congenital heart disease or chromosomal abnormalities and neonatal hypoglycaemia. Diagnosis is established by mid-trimester ultrasound scan. Management is primary closure or staged reduction to achieve delayed closure.

Umbilical hernia

| Condition | Appearance | Management |

|---|---|---|

| Granuloma | Dull and irregular | Cauterisation or surface ligation after excluding an underlying, more serious lesion |

| Patent vitello-intestinal tract | Red, smooth and leaking digested milk | Specialised investigation and laparotomy for repair |

| Patent urachus | Leakage of urine | Urological investigation and repair |

Abdominal tumours

| Site | Tumour |

|---|---|

| Upper abdomen crossing midline | Neuroblastoma Ganglioneuroma Lymphoma |

| Loin | Wilms’ tumour (the commonest cause of a solid renal mass in a child) |

| Pelvis | Urogenital cysts Neuroblastoma arising from pelvic sympathetic ganglia Presacral teratomas Ovarian cysts |

| Right upper quadrant | Hepatic haemangioma and hepatoblastoma |