Paediatric skull—suspected NAI

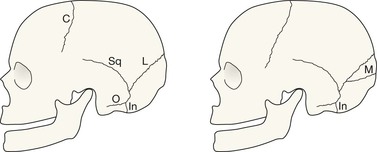

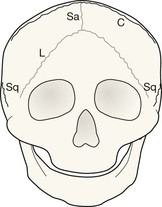

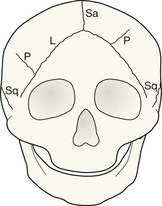

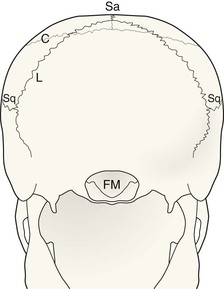

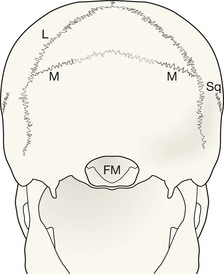

Normal anatomy

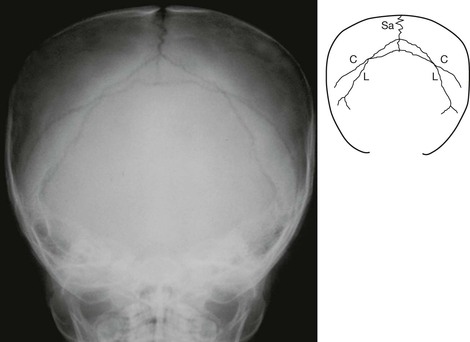

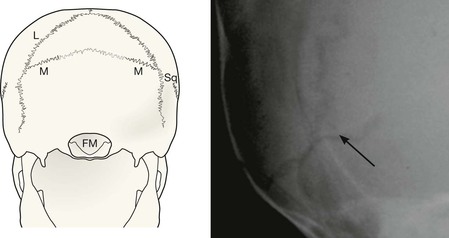

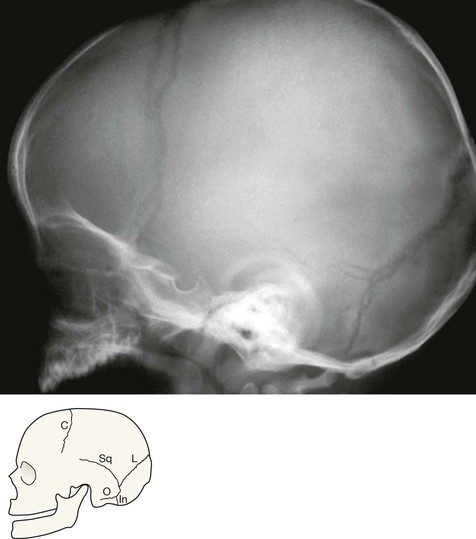

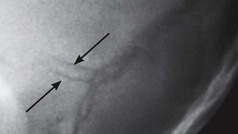

Infants and toddlers—normal accessory sutures

Evaluating the SXR in an infant or toddler presents unique problems. Diagnostic confusion between sutures and fractures may have serious consequences. A basic understanding of the locations and variable appearances of these sutures will help to reduce the likelihood of misdiagnosis4–8.

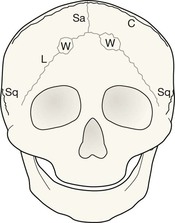

A basic classification of skull sutures in infants and toddlers

| Grouping | Notes | Sutures |

| The normal sutures | Visible on the SXR in all infants and toddlers – persisting in all adults | Sagittal, coronal, lambdoid, squamosal, and smaller sutures around the mastoid |

| A normal developmental suture | Visible on the SXR in all infants and many toddlers – but not in adults | Innominate |

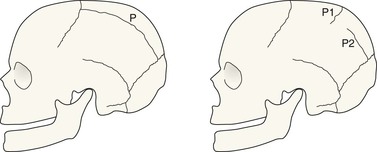

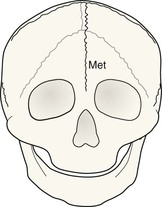

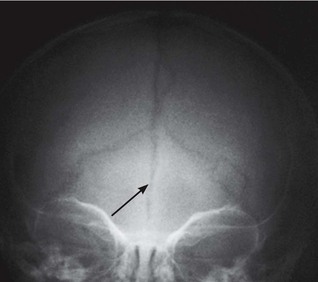

| The most common accessory sutures | Visible on the SXR in some infants and toddlers – occasionally persisting to adulthood | Metopic, accessory parietal, mendosal |

Normal accessory sutures and the radiographs on which they are seen

| Suture | Most commonly seen on | Notes |

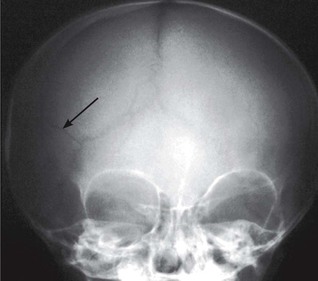

| Metopic suture | Frontal √ √ Towne’s √ |

The commonest accessory suture. It is also the one that most commonly persists in older children, and even in a few adults. |

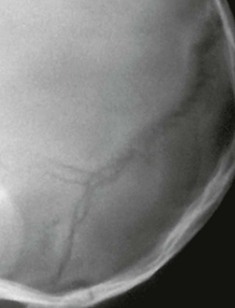

| Accessory parietal suture | Towne’s √ √ Frontal √ Lateral √ |

May be complete or incomplete. Occurs in vertical, horizontal or oblique orientations. Most commonly vertical. |

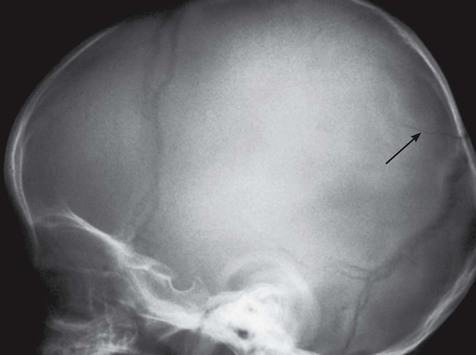

| Mendosal suture | Lateral √ √ Towne’s √ |

Extends posteriorly from the lambdoid suture on the lateral view. Passes medially on Towne’s view. |

| Innominate suture | Lateral √ √ | Sometimes classified as an accessory suture but best regarded as a normal developmental suture because it is always present in infants. As the child matures this suture disappears. |

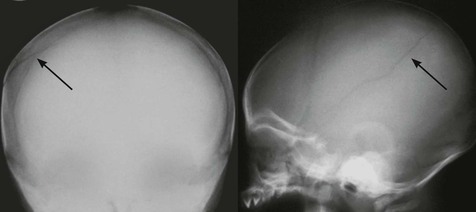

Analysis: suture recognition

The principal question: is it a suture or a fracture?4–8

When assessing suspected non-accidental injury (NAI) in young children, be very careful not to rush too swiftly to judgement. Observing an abnormality is important. An informed approach is then required when assigning a particular significance to the abnormality9–12.