Paediatric haematology

Normal values

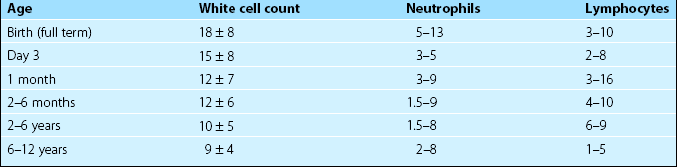

It is important to appreciate that the normal ranges for many haematological tests vary with age. Table 45.1 illustrates reference values for the total white cell count (WCC) and the differential count in children. More detailed listings of normal ranges of laboratory tests in childhood can be found in specialised paediatric haematology texts.

Neonatal disorders

Haemolytic disease of the newborn

Diagnosis

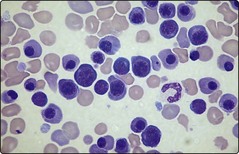

Severe HDN can result in intrauterine death. In the newborn child the presentation is entirely dependent on the degree of haemolysis but common features include anaemia, jaundice, oedema and hepatosplenomegaly. High levels of circulating unconjugated bilirubin may lead to high frequency deafness or deposition in the basal ganglia with spasticity and other neurological symptoms and signs (‘kernicterus’). Further investigation of the anaemia reveals features typical of haemolysis (Fig 45.1) with a positive direct antiglobulin test (DAT). In HDN due to RhD incompatibility the baby is RhD positive and the mother RhD negative with a high level of anti-D.

RhD prophylaxis in RhD-negative mothers

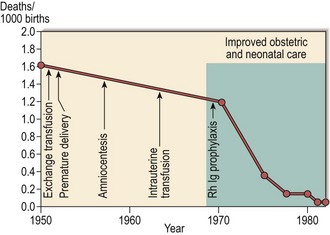

The breakthrough in the prevention of HDN has been the introduction of prophylaxis (Fig 45.2). A dose of Rh anti-D immunoglobulin (Ig) is given to all RhD-negative mothers who deliver a RhD-positive infant. A larger than average feto-maternal haemorrhage necessitates a greater dose of anti-D Ig. It is most likely that anti-D administration prevents HDN by a negative modulation of the primary immune response rather than by simple removal of fetal RhD-positive cells. General recommendations for Rh prophylaxis are shown in Table 45.2. As some women undoubtedly become sensitised earlier in a normal pregnancy, routine antenatal prophylaxis is widely recommended.

Table 45.2

Recommendations for Rh prophylaxis1

Rh prophylaxis after delivery

Anti-D (usually 500 IU) is given within 72 hours in RhD-negative mothers where the infant is RhD positive (or group undetermined). If there is a large feto-maternal haemorrhage (assessed in a Kleihauer test) additional anti-D is given

Rh prophylaxis and abortions

In RhD-negative mothers anti-D is given after all therapeutic abortions and after spontaneous or threatened abortions later than 12–13 weeks’ gestation and in selected cases of threatened abortion before 12 weeks (usual dose 250 IU before 20 weeks and 500 IU after 20 weeks)

Rh prophylaxis during pregnancy

Anti-D is given after possible sensitising events in RhD-negative women. These include: amniocentesis, chorionic villus sampling, abdominal trauma, external cephalic version, antepartum haemorrhage, ectopic pregnancy (usual dose of anti-D is 250 IU before 20 weeks and 500 IU after 20 weeks). Anti-D (500 IU) should be given to non-sensitised RhD-negative mothers at 28 and 34 weeks

Thrombocytopenia in the neonate

Some causes of thrombocytopenia in neonates are listed in Table 45.3. In practice the major divide is between seriously ill infants where the low platelet count is caused by disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), and relatively well infants where thrombocytopenia is most often of immune aetiology or occurs secondary to a specific inherited syndrome. Immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) may be seen in infants born to mothers with ITP where there is passive transfer of IgG across the placenta. Alloimmune thrombocytopenia arises where the healthy mother becomes sensitised against a fetal platelet antigen in a manner analogous to HDN; the platelet antigen HPA-1a is most commonly implicated.