Chapter 37. Paediatric cardiac arrest

Introduction

Cardiorespiratory arrest in children is a much rarer event than in adults. Unfortunately, the outcome for children is much worse. In children the underlying event is usually hypoxia followed by a respiratory arrest and it is easier to prevent paediatric respiratory arrest than to treat it. For the youngest children (i.e. infants) the most common clinical cause is sudden infant death syndrome. For older children, the underlying cause is hypoxia which is secondary to severe sepsis, drowning, poisoning, aspiration and trauma.

Basic life support

Infants (aged under 1 year)

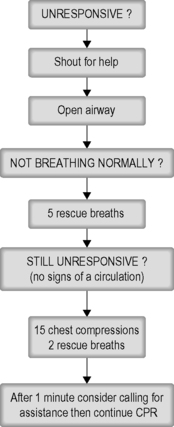

• For infants, basic life support (BLS) starts with checking for responsiveness by shaking while shouting for help

• The next step is to open the airway by tilting the head and lifting the chin

• When this is achieved, the presence of breathing is assessed by looking, listening and feeling for any signs of respiration

• If breathing is found to be absent deliver five rescue breaths. When this has been performed, the next step is to check for a brachial pulse.

|

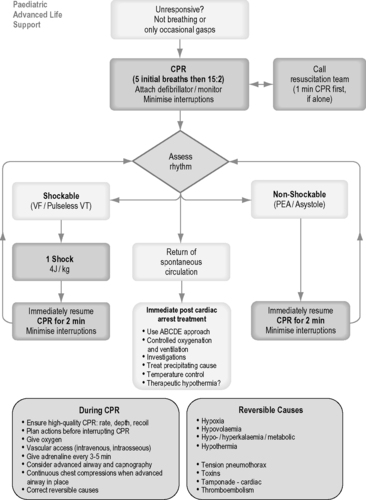

| Figure 37.1. |

| Paediatric basic life support (Resuscitation Council UK). The authors are aware of impending changes in resuscitation guidelines (late 2010). Refer to: www.resus.org.uk for further up-to-date information. |

In infants check the brachial pulse

• If the pulse is absent or the infant is found to be significantly bradycardic (i.e. the pulse rate is less than 60/min) then chest compressions should begin

• To achieve this, two fingers are placed on the lower sternum, a finger’s breadth beneath the nipple line. The chest is compressed by approximately one-third of its depth and five rapid compressions are administered

• Alternatively, use the encircling technique. Place both thumbs, side by side, on the lower third of the sternum with the tips pointing towards the infant’s head, encircle the lower part of the rib cage with the fingers and depress the rib cage with the thumbs by at least one-third of the depth of the chest.

• If the pulse is below 60/min, commence basic life support

• Ratio of: 15 chest compressions : 2 rescue breaths

• Rate 100–120 compressions per minute.

The paramedic crew attending such a call should continue basic life support measures while more advanced life support techniques are considered.

Children (aged over 1 year)

• For children over 1 year old, the same algorithm is followed with some slight differences

• Cardiac output can be established by feeling the carotid pulse

• Chest compressions can be given with the heel of one hand or with a two-handed technique, whichever is the most effective for the size of the patient

• In both instances the heel of one hand is placed on the lower sternum, one finger’s breadth above the xiphisternum, and the chest compressed by one-third of its depth.

Advanced life support

Basic life support should not be interrupted while advanced life support equipment is prepared. The patient should be placed on cardiac monitoring and the underlying rhythm determined. Intubation may be required. Intravenous or intraosseous access should be obtained in order to give drugs.

The size of the endotracheal tube used for intubation and the dosage of the drugs used in arrest depend on the age and size of the child. Two important formulae will assist the paramedic to choose correctly. To estimate the weight of the child, 4 is added to the child’s age in years and the result doubled. For instance, a 4-year-old child will weigh approximately 16 kg.

Weight (kg) = (age in years + 4) × 2

To estimate the endotracheal tube size (internal diameter in mm), the age is divided by 4 and 4 added:

Endotracheal tube size = (age in years/4) + 4

For example, a 6-year-old child would require an endotracheal tube of 5.5 mm.

Arrest algorithms

When the child is placed on a cardiac monitor, the first decision, as in adult practice, is to determine which arrest rhythm the child is suffering from.

Asystole

• Asystole is by far the most common rhythm found in paediatric cardiac arrest

• The treatment is intubation and ventilation with supplemental oxygen to try to give an inspired oxygen content of 100%. Circulatory access should then be gained as rapidly as possible

• Once access is achieved, adrenaline in a dose of 10 μg/kg is administered. Pre-filled syringes of 1 mg adrenaline in 10 mL should be used (1:10 000)

• Consider giving the child a fluid bolus, normally 20 mL/kg of normal saline, particularly if the history suggests hypovolaemia.

Pulseless electrical activity

PEA can be found in paediatric practice. The treatment is as per the algorithm:

• Intubation

• Ventilation with 100% oxygen

• Intravenous or intraosseous access

• Adrenaline 10 μg/kg every 3–5 minutes

• IV fluid bolus 20 mL/kg

• CPR in 2-minute cycles

• Consideration of underlying cause of EMD

• PEA is usually secondary to some known cause, such as profound hypovolaemia, tension pneumothorax, cardiac tamponade, drug overdose or hypothermia

• Since hypovolaemia is common, it is reasonable to administer a challenge of 20 mL/kg of fluid such as normal saline for this particular arrest rhythm unless it is specifically contraindicated.

Ventricular fibrillation

• VF in paediatric cardiac arrest occurring out of hospital is rare

• VF may occur typically with some poisons, such as with tricyclic antidepressant drugs, and also with drowning in cold water and hypothermia

• A shock should be delivered immediately at 4 J/kg. As for adults, the 2 minute cycle of CPR should be completed before reassessing for output

• 2 minute cycles should be continued with one shock per cycle as necessary

• The patient should be intubated and ventilated

• Access should be gained and adrenaline administered every 3–5 minutes (Table 37.1)

• If unsuccessful after three cycles, consider the use of amiodarone, in a dose of 5 mg/kg.

Automatic external defibrillators

• The energy delivery from most automatic defibrillators (AEDs) is fixed at that which is appropriate for adults

• Purpose made paediatric pads, or devices/programs which attenuate the energy output of an AED are recommended for children between 1 and 8 years

• An adult AED can still be used in all patients over the age of 1 year if there is no other option.

Continuation of care

If an output is achieved then begin post-resuscitation care, otherwise transport to hospital must be carried out without any break in CPR. It is vital to warn the receiving hospital so that they can assemble a paediatric resuscitation team for your arrival.

For further information, see Ch. 37 in Emergency Care: A Textbook for Paramedics.