Paediatric biochemistry

Immaturity

Jaundice

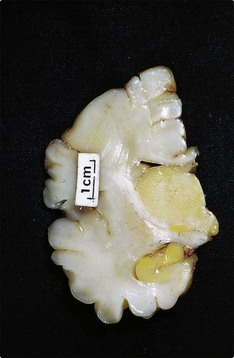

Persistent jaundice due to unconjugated hyperbilirubinaemia should not be ignored. Unconjugated bilirubin is lipophilic and can cross the blood–brain barrier and bind to proteins in the brain where it is neurotoxic. This happens when albumin (the normal carrier of unconjugated bilirubin) becomes saturated. The clinical syndrome of bilirubin-encephalopathy is called kernicterus (Fig 79.1) and may result in death or severe mental handicap. Where the excess bilirubin is found to be conjugated, the pathology is different, and kernicterus is not a feature, since conjugated bilirubin is water-soluble rather than lipophilic. Causes include neonatal hepatitis, possibly contracted from the mother at birth; biliary atresia, resulting in severely impaired biliary drainage; and inherited deficiency of alpha-1-antitrypsin, a powerful protease, the absence of which is associated with liver and lung damage.

Hypoglycaemia

Before birth, the chief source of energy for the fetus is glucose obtained from the mother via the placenta. Any excess glucose is stored as liver glycogen. Free fatty acids cross the placenta and are stored in fat tissue. At birth the baby suddenly has to switch to its own homeostatic mechanisms in order to maintain its blood glucose concentration in between feeds. These include gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis. However, glycogen stores are often insufficient to prevent neonatal hypoglycaemia. Lipolysis provides another energy source in the form of free fatty acids until feeding is established. Hypoglycaemia including neonatal hypoglycaemia is dealt with on pp. 68–69.

Dehydration

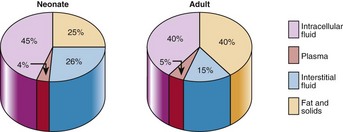

The total body water of a newborn baby is around 75% of body weight, compared with 60% in the adult (Fig 79.2). In the first week after birth, the ECF contracts and this explains why most babies initially lose some weight before gaining it back subsequently. Infants are very vulnerable to fluid loss because their renal tubular function is not fully mature. Their ability to concentrate urine (and hence retain water) is poor – the maximum urine osmolality that can be produced is about 600 mmol/kg, compared with in excess of 1200 mmol/kg in a healthy adult. In addition, reabsorption of bicarbonate and glucose is reduced, leading to a low serum bicarbonate and glycosuria respectively.

Prematurity

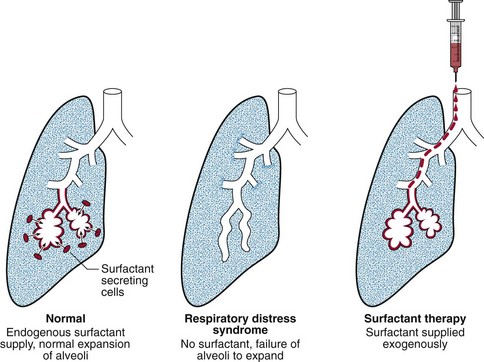

Prematurity presents an even more extreme challenge to organ function. A good example of organ failure resulting from prematurity is respiratory distress syndrome. Babies born before 32 weeks’ gestation are unlikely to be able to make their own pulmonary surfactant, resulting in respiratory distress syndrome due to failure of alveolar expansion. Measurement of the lecithin/sphingomyelin ratio was used in the past in the assessment of fetal lung maturity, but has largely been superseded by the advent of surfactant therapy. Figure 79.3 illustrates the role of surfactant.

Practical considerations

Sampling. Although venepuncture is preferred in older children, heelprick sampling is less traumatic for very young children. Heel puncture can, however, be complicated by calcaneal osteomyelitis, and there are preferred sites of collection (see p. 156).

Sampling. Although venepuncture is preferred in older children, heelprick sampling is less traumatic for very young children. Heel puncture can, however, be complicated by calcaneal osteomyelitis, and there are preferred sites of collection (see p. 156).

Sample volume. This is a major issue for paediatric biochemistry laboratories. A premature baby weighing less than 1000 g may have as little as 75 mL total blood volume. The sample volume must, therefore, be kept to an absolute minimum. At low sample volumes, e.g. 100 µL, evaporation from uncovered specimens can alter results of analyses by as much as 10% in 1 hour.

Sample volume. This is a major issue for paediatric biochemistry laboratories. A premature baby weighing less than 1000 g may have as little as 75 mL total blood volume. The sample volume must, therefore, be kept to an absolute minimum. At low sample volumes, e.g. 100 µL, evaporation from uncovered specimens can alter results of analyses by as much as 10% in 1 hour.

Plasma or serum. In most laboratories that process paediatric specimens, plasma is preferred. In principle the turnaround time is reduced because one does not have to wait for clotting to occur before centrifuging the sample. Also there is generally less haemolysis.

Plasma or serum. In most laboratories that process paediatric specimens, plasma is preferred. In principle the turnaround time is reduced because one does not have to wait for clotting to occur before centrifuging the sample. Also there is generally less haemolysis.

Interferences. Haemolysis increases plasma concentrations of potassium and some other analytes that are present in higher concentrations in red blood cells than in extracellular fluid. Hyperbilirubinaemia can interfere with creatinine measurement.

Interferences. Haemolysis increases plasma concentrations of potassium and some other analytes that are present in higher concentrations in red blood cells than in extracellular fluid. Hyperbilirubinaemia can interfere with creatinine measurement.

Instrumentation. Automated analysers must be chosen with sample size in mind, as well as the ‘dead volume’ (the amount of sample that must remain in the sample cup after the sample has been aspirated for analysis); both of these should be kept to a minimum. Common interferences should, ideally, not affect results. Some analysers make use of dry slide technology to prevent interferences.

Instrumentation. Automated analysers must be chosen with sample size in mind, as well as the ‘dead volume’ (the amount of sample that must remain in the sample cup after the sample has been aspirated for analysis); both of these should be kept to a minimum. Common interferences should, ideally, not affect results. Some analysers make use of dry slide technology to prevent interferences.