2.2 Paediatric basic life support

Paediatric versus adult basic life support

Anatomy and physiology

Preparation and equipment

Basic life support sequence

A ‘SAFE’ approach

Airway

Open and maintain the airway

Three manoeuvres will assist in opening and maintaining the airway (Figs 2.2.1, 2.2.2 and 2.2.3), which is most commonly obstructed by the child’s tongue.

Circulation

Chest compressions

The technique of providing ECC varies with the patient’s age.

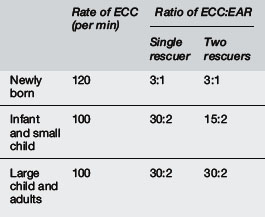

Compression to ventilation ratio

For a lone rescuer, external cardiac compressions should be combined with expired air resuscitation in a ratio of 30 compressions to 2 ventilations for all age groups (except neonates – see below). Healthcare providers performing two-rescuer BLS should use a ratio of 15 compressions to 2 ventilations for all infants and children (see Table 2.2.1). Note that the ratio of 30:2 is utilised in adults regardless of the number of rescuers.

Relief of foreign body airway obstruction

FBAO management in the unresponsive patient

The sequence of response for an unresponsive, apnoeic patient with FBAO is as follows:

Open the airway using chin lift or jaw thrust. Look inside the mouth and remove any visible foreign body. Do not perform a blind finger sweep because of the risk of damaging palatal tissues or pushing a foreign body further into the airway.

Open the airway using chin lift or jaw thrust. Look inside the mouth and remove any visible foreign body. Do not perform a blind finger sweep because of the risk of damaging palatal tissues or pushing a foreign body further into the airway. If rescue breaths are still unsuccessful, perform a sequence of five back blows and five chest thrusts.

If rescue breaths are still unsuccessful, perform a sequence of five back blows and five chest thrusts.

If the obstruction is not relieved, continue the above sequence until the obstruction is relieved or for approximately one minute. If the patient remains unresponsive at one minute, seek help. If the patient is small enough, the rescuer should take the patient with them and attempt to continue FBAO relief manoeuvres whilst seeking help. If the patient is too large to be moved, the rescuer should position the patient appropriately and leave to seek help.

If the obstruction is not relieved, continue the above sequence until the obstruction is relieved or for approximately one minute. If the patient remains unresponsive at one minute, seek help. If the patient is small enough, the rescuer should take the patient with them and attempt to continue FBAO relief manoeuvres whilst seeking help. If the patient is too large to be moved, the rescuer should position the patient appropriately and leave to seek help.For management in the emergency department setting see inhaled FB (Chapter 6.2).

FBAO management in the unresponsive child

Advanced Life Support Group. Advanced paediatric life support: The practical approach, 4th rev. ed. BMJ Publishing Group: London, 2004.

3 Australian Resuscitation Council Guidelines. sections 12 and 13 http://www.resus.org.au/; December 2010

Biarent D., Bingham R., Eich C., et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation. Section 6: Paediatric life support. Resuscitation. 2010;81(10):1364-1368.

International Liaison Committee (ILCOR). Consensus on Science with Treatment Recommendations for Pediatric and Neonatal Patients: Pediatric Basic and Advanced Life Support. Pediatrics. 117(5), 2005.

Kleinman M.E., de Caen A.R., de Chameides L., et al. Part 10: Pediatric basic and advanced life support: 2010 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science With Treatment Recommendations. Circulation. 2010;16(Suppl 2):S466-515.

Richmond S., Wyllie J. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation. Section 7: Resuscitation of babies at birth. Resuscitation. 2010;8(10):1389-1399.