P

P value, see Probability

P wave. Component of the ECG representing atrial depolarisation. Normally positive (i.e. upwards) in lead I, and best seen in leads II and V1 (see Fig. 59b; Electrocardiography). Maximal amplitude is normally 2.5 mm in lead II, and its duration 0.12 s (three small squares). In right atrial enlargement, the P wave is tall and peaked (P pulmonale); in left atrial enlargement, it is wide and notched (P mitrale).

Pacemaker cells. Cardiac muscle cells that undergo slow spontaneous depolarisation to initiate action potentials. Their activity results from a slow decrease in membrane potassium ion permeability, resulting in gradual increase in intracellular potassium concentration. Rate of discharge depends on the slope of phase 4 depolarisation, resting membrane potential and threshold potential. Pacemaker cells exist in the sinoatrial (SA) node, atrioventricular (AV) node, bundle of His and ventricular cells. Spontaneous rates of discharge for the different sites: SA node 70–80/min, AV node 60/min, His bundles 50/min and ventricular cells 40/min. Impulses from the faster SA node usually reach and excite the slower pacemaker cells before the latter can discharge spontaneously.

Pacemakers. Devices implanted subcutaneously, usually outside the thorax, that provide permanent cardiac pacing (to distinguish them from temporary pacing devices).

Indicated if an arrhythmia is associated with syncope, dizziness and cardiac failure, e.g. in sick sinus syndrome, heart block or post-MI. Prophylactic use is controversial.

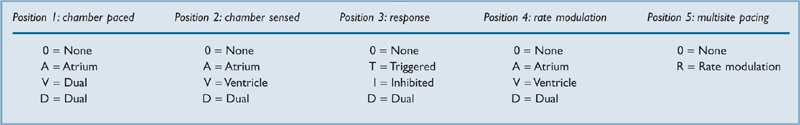

A generic pacemaker code identifies function (Table 34), the first three positions indicating basic pacing function. Thus VVI denotes ventricular pacing and sensing, with inhibition of pacing if any spontaneous ventricular complex occurs (e.g. as would apply in temporary transvenous pacing). DDD denotes pacing and sensing of both chambers, with inhibition or triggering to maintain sequential atrial and ventricular contraction, allowing spontaneous activity if it occurs. Rate modulation implies the ability to alter the heart rate in response to the patient’s level of activity; rate-adaptive devices respond to physiological parameters normally associated with changes in heart rate (e.g. body movement, Q–T interval, respiration, temperature, pH, myocardial contractility, haemoglobin saturation) by increasing the pacing rate. The fifth position is allocated to multisite pacing, which refers to stimulation of different sites either within one chamber (e.g. right ventricle) or within two chambers of the same type (e.g. both ventricles). With the development of implantable cardioverter defibrillators, much of the latter functions are covered within the defibrillator codes (see Defibrillators, implantable cardioverter).

• Anaesthesia for patients with pacemakers:

– preoperative assessment is particularly directed towards the CVS.

– ECG:

– if pacing spikes occur before all or most beats, heart rate is pacemaker-dependent.

– CXR: pulse generator and lead position may be identified.

– potential electrical interference or pacemaker damage by diathermy is more likely if the latter is applied near the device. Sensing may be triggered, with resultant chamber inhibition, or arrhythmias induced. Diathermy may also reprogramme the pacemaker to a different mode.

– care should be taken with CVP/pulmonary artery catheters since they may dislodge the electrodes.

– isoprenaline may be required if pacemaker failure occurs.

– alteration of pacemaker sensitivity by halothane has been described in older pacemaker models.

– avoidance of suxamethonium has been suggested in case fasciculations are sensed as arrhythmias.

– MRI may be hazardous since the pacemaker may be switched to asynchronous mode, may fail altogether or may move within the chest.

American Society of Anesthesiologists (2011). Anesthesiology; 114: 247–61

Packed cell volume, see Haematocrit

Paediatric Advanced Life Support (PALS). Course set up in the USA by the American Heart Association and the American Academy of Pediatrics. Intended for healthcare professionals caring for acutely ill children (e.g. those working in paediatric, anaesthetic, intensive care and emergency departments). Course objectives include:

Kleinman ME, Chameides L, Schexnayder SM, et al (2010). Circulation; 122 (suppl 3): S876–908

Paediatric anaesthesia. Main considerations are related to the anatomical and physiological differences between adults and children, especially neonates (defined as < 1 month old; infants are < 1 year old).

• Thus in children compared with adults:

– the tongue is large and the larynx situated more anteriorly and cephalad (C3–4). The epiglottis is large and U-shaped. A straight laryngoscope blade is thus often preferred for tracheal intubation, and the head should be in the neutral position (as opposed to the ‘sniffing position’ in adults).

– the cricoid cartilage is the narrowest part of the upper airway up to 8–10 years of age (cf. glottis in adults). A small decrease in diameter (e.g. caused by oedema or stricture formation following prolonged tracheal intubation) may lead to airway obstruction.

– the left and right main bronchi arise at equal angles from the trachea. At birth, the tracheobronchial tree is developed as far as the terminal bronchioles. Alveoli number 20 million, increasing to 300 million by 6–8 years.

– respiration is predominantly diaphragmatic, and sinusoidal and continuous instead of periodic. Neonates are obligatory nose breathers. Respiratory rate is increased. Tidal volume is about 7 ml/kg as in adults. The infant lung is more susceptible to atelectasis because the chest wall is more compliant and therefore pulled inwards by the lungs, decreasing FRC. Closing capacity may exceed FRC during normal respiration in neonates and infants. Surfactant may be deficient in premature babies.

– response to CO2 is reduced at birth, and irregular breathing may also occur. Premature babies may suffer from apnoeic episodes; they are at risk of postoperative apnoea up to about 50 weeks postconceptual age. Gasp and Hering–Breuer reflexes are active.

– basal metabolic rate and O2 consumption are high (the latter is 5–6 ml/kg/min, compared with about 3–4 ml/kg/min in adults). Hypoxaemia thus occurs more rapidly than in adults.

– the oxyhaemoglobin dissociation curve of fetal haemoglobin is shifted to the left (P50 of 2.4 kPa [18 mmHg]). Haemoglobin concentration falls from 18 g/dl (1–2 weeks of age) to 11 g/dl (6 months–6 years).

– cardiac output is 30–50% higher than in adults, largely due to increased heart rate. Arterial BP is lower (Table 35).

Table 35 Normal heart rate and BP at different ages

| Age | Heart rate (beats/min) | BP (mmHg) |

| 0–6 months | 120–180 | 80/45 |

| 3 years | 95–120 | 95/65 |

| 5 years | 90–110 | 100/65 |

| 10 years | 80–100 | 110/70 |

– left and right ventricles are similar at birth, the former fibrous and non-compliant, making stroke volume relatively fixed.

– blood volume at birth is up to 90 ml/kg (or 50 + haematocrit). It falls to 80 ml/kg for children and 70 ml/kg by 14 years.

– veins are more difficult to cannulate.

– reversion to fetal circulation may occur in severe hypoxaemia.

– the spinal cord ends at L3 at birth, receding to L1–2 by adolescence.

– the immature blood–brain barrier results in increased sensitivity to centrally depressant drugs, particularly opioid analgesic drugs.

– vagal reflexes are particularly active in children. Bradycardia readily occurs in hypoxaemia.

– subependymal vessels are fragile in premature neonates, with risk of rupture if BP and ICP increase.

temperature regulation is impaired. Ratio of body surface area to body weight is greater than in adults and there is less body fat. Thus heat loss is rapid, compounded by impaired shivering and increased metabolic rate. Brown fat is metabolised to maintain body temperature. Insensible water loss is increased in premature babies.

temperature regulation is impaired. Ratio of body surface area to body weight is greater than in adults and there is less body fat. Thus heat loss is rapid, compounded by impaired shivering and increased metabolic rate. Brown fat is metabolised to maintain body temperature. Insensible water loss is increased in premature babies.

prolonged fasting may cause hypoglycaemia in small children, and oral clear fluids are usually allowed up to 2 h preoperatively (4 h for milk). IV administration of dextrose may be required.

prolonged fasting may cause hypoglycaemia in small children, and oral clear fluids are usually allowed up to 2 h preoperatively (4 h for milk). IV administration of dextrose may be required.

fluid balance is delicate, since a greater proportion of body water is exchanged each day. Total body water is normally increased, with a higher ratio of ECF to intracellular fluid (ECF exceeds intracellular fluid in premature babies). The kidneys are less able to handle a water or solute load, or to conserve water or solutes. Thus dehydration readily occurs in illness.

fluid balance is delicate, since a greater proportion of body water is exchanged each day. Total body water is normally increased, with a higher ratio of ECF to intracellular fluid (ECF exceeds intracellular fluid in premature babies). The kidneys are less able to handle a water or solute load, or to conserve water or solutes. Thus dehydration readily occurs in illness.

4 ml/kg/h for each of the first 10 kg, plus

2 ml/kg/h for each of the next 10 kg, plus

1 ml/kg/h for each kg thereafter.

More recently, because of the risk of perioperative hyponatraemia (children being at particular risk from resultant encephalopathy), and because perioperative hypoglycaemia is less of a problem than traditionally thought, there has been a move away from hypotonic solutions such as dextrose/saline, with maintenance fluids given as 0.45–0.9% saline or Hartmann’s solution, and isotonic fluids avoided if plasma sodium concentration is under 140 mmol/l.

Blood is traditionally given above 10% of blood volume loss, but larger blood losses are increasingly allowed if starting haemoglobin concentration is high. In hypovolaemia, 10 ml/kg colloid is a suitable starting regimen.

actions of drugs may be affected by the above factors, or by lower plasma albumin levels (up to 1 year of age), resulting in greater amounts of free drug. Renal and hepatic immaturity may contribute to reduced clearance. MAC of inhalational anaesthetic agents is increased in neonates, but may be reduced in premature babies. Neonates are more sensitive to non-depolarising neuromuscular blocking drugs, probably due to altered pharmacokinetics. They may be resistant to suxamethonium, requiring up to twice the adult dose.

actions of drugs may be affected by the above factors, or by lower plasma albumin levels (up to 1 year of age), resulting in greater amounts of free drug. Renal and hepatic immaturity may contribute to reduced clearance. MAC of inhalational anaesthetic agents is increased in neonates, but may be reduced in premature babies. Neonates are more sensitive to non-depolarising neuromuscular blocking drugs, probably due to altered pharmacokinetics. They may be resistant to suxamethonium, requiring up to twice the adult dose.

• Practical conduct of anaesthesia:

children are placed first on the operating list, to allow as short a fasting time as possible.

children are placed first on the operating list, to allow as short a fasting time as possible.

premedication is often given orally, to avoid injections, but standard im drugs are also given. Rectal administration has also been used. Atropine may be given to reduce excessive secretions and vagal reflexes.

premedication is often given orally, to avoid injections, but standard im drugs are also given. Rectal administration has also been used. Atropine may be given to reduce excessive secretions and vagal reflexes.

– cyclopropane was popular but is no longer available in the UK. Halothane has been replaced by sevoflurane. Inhalational induction is rapid because of increased alveolar ventilation, a low FRC and a high cerebral blood flow.

– standard iv anaesthetic agents are suitable. Administration im (e.g. ketamine) is also used. EMLA or topical tetracaine (amethocaine) is routinely used before iv induction.

The presence of parents at induction is usually allowed, depending on the circumstances.

appropriately sized laryngoscope handles and blades are employed. Uncuffed tracheal tubes are commonly used (usually until ~10 years), with a small air leak at 15–25 cmH2O airway pressure, to avoid subglottic stenosis. The approximate size may be calculated thus:

appropriately sized laryngoscope handles and blades are employed. Uncuffed tracheal tubes are commonly used (usually until ~10 years), with a small air leak at 15–25 cmH2O airway pressure, to avoid subglottic stenosis. The approximate size may be calculated thus:

– diameter = (age/4) + 4.5 mm.

– under 750 g/26 weeks’ gestation: 2.0–2.5 mm.

– 750–2000 g/26–34 weeks: 2.5–3.0 mm.

– over 2000 g/34 weeks: 3.0–3.5 mm.

dead space and resistance should be minimal in anaesthetic breathing systems; adult forms are suitable if the child weighs over 20–25 kg but the Bain system is often avoided because of increased resistance to expiration. Ayre’s T-piece is suitable up to 25 kg. Spontaneous ventilation via a facemask or LMA is usually suitable for short procedures in children older than 3 months. Below this, tracheal intubation and IPPV are traditionally performed, although the LMA is preferred by some.

dead space and resistance should be minimal in anaesthetic breathing systems; adult forms are suitable if the child weighs over 20–25 kg but the Bain system is often avoided because of increased resistance to expiration. Ayre’s T-piece is suitable up to 25 kg. Spontaneous ventilation via a facemask or LMA is usually suitable for short procedures in children older than 3 months. Below this, tracheal intubation and IPPV are traditionally performed, although the LMA is preferred by some.

– 10–30 kg: 1000 ml + 100 ml/kg per min.

– > 30 kg: 2000 ml + 50 ml/kg per min.

Set minute volume should equal twice fresh gas flow.

routine monitoring, including temperature measurement.

routine monitoring, including temperature measurement.

anaesthetic rooms and operating theatres should be warmed. Warming blankets and reflective coverings should also be used, with humidification of inspired gases.

anaesthetic rooms and operating theatres should be warmed. Warming blankets and reflective coverings should also be used, with humidification of inspired gases.

tracheal extubation may be performed with the child awake or anaesthetised, depending on the clinical context.

tracheal extubation may be performed with the child awake or anaesthetised, depending on the clinical context.

regional techniques are effective for peri- and postoperative analgesia, e.g. caudal analgesia, inguinal field block, penile block. Local wound infiltration is also effective. Spinal and epidural anaesthesia have also been used.

regional techniques are effective for peri- and postoperative analgesia, e.g. caudal analgesia, inguinal field block, penile block. Local wound infiltration is also effective. Spinal and epidural anaesthesia have also been used.

paracetamol and codeine are often used for postoperative analgesia, with morphine for severe pain. Antiemetic drugs are given as required; ondansetron and cyclizine are commonly used.

paracetamol and codeine are often used for postoperative analgesia, with morphine for severe pain. Antiemetic drugs are given as required; ondansetron and cyclizine are commonly used.

• Other problems are related to the procedure performed, e.g.:

repair of congenital defects, e.g. tracheo-oesophageal fistula, pyloric stenosis, gastroschisis, diaphragmatic hernia, congenital heart disease.

repair of congenital defects, e.g. tracheo-oesophageal fistula, pyloric stenosis, gastroschisis, diaphragmatic hernia, congenital heart disease.

The National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death (as NCEPOD) focused for its first year on paediatric anaesthesia. It concluded that general care was good, although outcome was related to clinicians’ experience.

Paediatric intensive care. Classified into levels 1, 2 and 3, primarily on the basis of interventions undertaken. Level 1 is high dependency care; level 3 is almost always provided in tertiary paediatric centres. In general, differs from adult intensive care by virtue of anatomical and physiological differences between adults and children (see Paediatric anaesthesia) and the range of conditions seen.

• Main clinical problems encountered include:

– neonates: choanal atresia, congenital facial deformities, laryngeal/tracheal abnormalities.

– infants/children: inhaled foreign body, tonsillar/adenoidal hypertrophy, croup, epiglottitis and angioedema.

– neonates: meconium aspiration, respiratory distress syndrome, diaphragmatic hernia, pneumothorax, chest infection.

– infants/children: pneumonia, asthma, bronchiolitis, cystic fibrosis, congenital heart disease, trauma, near-drowning, burns.

– in neonates, respiratory impairment may result in the development of a persistent fetal circulation.

– neonates: birth asphyxia, central apnoea, convulsions.

– infants/children: meningitis, encephalitis, status epilepticus, Guillain–Barré syndrome.

– head injury occurs in 50% of cases of blunt trauma. A modified Glasgow coma scale is used for assessment; otherwise, management is along similar lines to that of adults.

– spinal cord injury and thoracic/abdominal trauma is usually caused by road traffic accidents.

• Specific attention must be paid to:

smaller equipment, drug doses and fluid volumes; specialised equipment.

smaller equipment, drug doses and fluid volumes; specialised equipment.

nutrition and electrolyte/fluid balance.

nutrition and electrolyte/fluid balance.

sedation and analgesia.

sedation and analgesia.

educational and psychological needs.

educational and psychological needs.

the risk of retinopathy of prematurity in neonates.

the risk of retinopathy of prematurity in neonates.

Overall mortality ranges from 5 to 10% depending on admission criteria. Scoring systems such as the paediatric trauma score, injury severity score and paediatric risk of mortality score attempt to predict outcome and allow audit of care within and between units.

Frey B, Argent A (2004). Intensive Care Med; 30: 1041–6, 1292–7

See also, Brainstem death; Cardiopulmonary resuscitation, neonatal; Cardiopulmonary resuscitation, paediatric; Necrotising enterocolitis

Paediatric logistic organ dysfunction score (PELOD). Scoring system for the severity of multiple organ dysfunction in paediatric intensive care. Based on 12 variables relating to six organ systems (neurological, cardiovascular, renal, respiratory, haematological and hepatic). Has been used as daily indicator of organ dysfunction.

Leteurtre S, Martinot A, Duhamel A, et al (2003). Lancet; 362: 192–7

Paediatric risk of mortality score (PRISM). Scoring system used in paediatric intensive care to help predict mortality. Originally used weighted scores for 14 variables related to acute physiological status; the latest version (PRISM III) has 17 and includes additional risk factors, including acute and chronic diagnosis. Has been validated for most categories of paediatric ICU.

Pollack MM, Patel KM, Ruttimann UE (1996). Crit Care Med; 24: 743–52

Paediatric trauma score. Trauma scale designed to allow triage of paediatric patients. Six variables (weight, patency of airway, systolic BP, conscious level, presence of skeletal injury and skin injuries) attract scores of 2 (normal), 1 or –1 (severely compromised); scores under 8 indicate increased morbidity and mortality and require referral to a paediatric trauma centre.

Tepas JJ, Ramenofsky ML, Mollitt DL, et al (1988). J Trauma; 28: 425–9

Pain. Classically defined as an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience resulting from a stimulus causing, or likely to cause, tissue damage (nociception), or expressed in terms of that damage. Thus affected by subjective emotional factors, making pain evaluation difficult. Chronic pain may arise from nervous system dysfunction rather than tissue damage and may be associated with damage to pain pathways (neurogenic pain, e.g. trigeminal neuralgia, postherpetic neuralgia, complex regional pain syndrome type 2, phantom limb pain, central pain). Substances released from damaged tissues, and/or reorganisation of somatic and sympathetic spinal reflex pathways, are thought to be involved in the aetiology of chronic pain. Chronic pain is usually more difficult to diagnose and treat than acute pain, and psychological and emotional factors are more important.

See also, Allodynia; Dysaesthesia; Hyperaesthesia; Hyperalgesia; Hyperpathia; Hypoalgesia; Myofascial pain syndromes; Pain clinic; Pain management; Postoperative analgesia

Pain clinic. Outpatient clinic run by consultants (usually anaesthetists) with a special interest in the management of chronic pain. Its role includes diagnosis of the underlying condition and management directed at reducing subjective pain experiences, reducing drug consumption, increasing levels of normal activity and restoring a normal quality of life. Requires appropriate facilities for consultation, and performance of nerve blocks and surgical procedures. Anaesthetists, physicians, psychologists and neurologists may be involved. Primary referrals to the clinic are usually from general practitioners or hospital consultants.

Pain evaluation. Difficult to perform, because pain is a subjective experience.

• Methods used depend on the setting and whether the pain is acute or chronic:

experimental methods (e.g. assessing analgesic effects of new drugs):

experimental methods (e.g. assessing analgesic effects of new drugs):

acute pain, e.g. postoperative: linear analogue scale; using numbers or words to rate the degree of pain (patient and observer assessment may be used); demand for analgesia. Babies have been studied by recording and analysing their cries.

acute pain, e.g. postoperative: linear analogue scale; using numbers or words to rate the degree of pain (patient and observer assessment may be used); demand for analgesia. Babies have been studied by recording and analysing their cries.

Pain, intractable, see Pain; Pain clinic; Pain management; individual conditions

Pain management. Acute pain, e.g. postoperative, is usually treated with systemic analgesics and regional techniques (see Postoperative analgesia).

• Chronic pain management may involve the following, after pain evaluation:

simple measures, e.g. rest, exercise, heat and cold treatment, vibration.

simple measures, e.g. rest, exercise, heat and cold treatment, vibration.

– analgesic drugs: different drugs, dosage regimens and routes of administration may be chosen, depending on the severity and temporal pattern of the pain, and efficacy and side effects of the drugs. Drugs used range from mild NSAIDs to opioid analgesic drugs. The latter are usually reserved for severe pain of short duration, or pain associated with malignancy; they may require concurrent antiemetic and aperient therapy. Implantable devices may be used for intermittent iv, epidural or subarachnoid injection or continuous infusion of opioids.

– psychoactive drugs, e.g. antidepressant drugs, anticonvulsant drugs (e.g. pregabalin, gabapentin, carbamazepine). Of these, amitryptiline, pregabalin and duloxetine are suitable first-line agents for chronic/neuropathic pain.

– corticosteroids, either by local injection or oral therapy. Particularly useful in neuralgia or pain associated with oedema, e.g. malignancy. Often injected with local anaesthetic agents, e.g. epidurally for back pain.

– muscle relaxants, e.g. baclofen, dantrolene, benzodiazepines; may be useful if muscle spasm is problematic.

– others, e.g. antimitotic drugs, calcitonin in bony pain, β-adrenergic receptor antagonists, clonidine.

– injection of trigger points in myofascial pain syndromes.

– caudal analgesia, epidural anaesthesia, spinal anaesthesia.

– sympathetic nerve blocks, e.g. stellate ganglion, coeliac plexus and lumbar sympathetic blocks, iv guanethidine block.

neurolytic procedures: usually reserved for severe pain associated with malignancy, since relief may not be permanent and severe side effects may occur, e.g. anaesthesia dolorosa. X-ray guidance is usually employed to aid percutaneous neurolysis. Methods include:

neurolytic procedures: usually reserved for severe pain associated with malignancy, since relief may not be permanent and severe side effects may occur, e.g. anaesthesia dolorosa. X-ray guidance is usually employed to aid percutaneous neurolysis. Methods include:

– extremes of temperature, e.g. cryoprobe, radiofrequency probe. The latter delivers a high-frequency alternating current, producing up to 80°C heat. It is used at peripheral nerves, facet joints, dorsal root ganglia and trigeminal ganglion, and for percutaneous cordotomy.

– surgery: includes peripheral neurectomy, dorsal rhizotomy or lesions in the dorsal root entry zones (DREZ), commissurotomy (sagittal division of the spinal cord), mesencephalotomy and thalamotomy.

– TENS and electroacupuncture.

psychological techniques, e.g. psychotherapy, cognitive behavioural therapy, operant conditioning, hypnosis, biofeedback, relaxation techniques.

psychological techniques, e.g. psychotherapy, cognitive behavioural therapy, operant conditioning, hypnosis, biofeedback, relaxation techniques.

Pain pathways. Most pain arises in pain receptors (nociceptors) widely distributed in the skin and musculoskeletal system. Those responding to pinprick and sudden heat (thermomechanoreceptors) are associated with myelinated Aδ fibres, convey sharp pain sensation and are responsible for rapid pain transmission and reflex withdrawal. Receptors responding to pressure, heat, chemical substances (e.g. histamine, prostaglandins, acetylcholine) and tissue damage (polymodal receptors) are associated with unmyelinated C-fibre endings, and are responsible for dull pain sensation and immobilisation of the affected part.

• Afferent impulses pass centrally thus:

first-order neurones have cell bodies within the dorsal root ganglia of the spinal cord. Aδ fibres synapse with cells in laminae I and V of the cord, whilst C fibres synapse with cells in laminae II and III (substantia gelatinosa).

first-order neurones have cell bodies within the dorsal root ganglia of the spinal cord. Aδ fibres synapse with cells in laminae I and V of the cord, whilst C fibres synapse with cells in laminae II and III (substantia gelatinosa).

The substantia gelatinosa does not project directly to higher levels, but contains many interneurones involved in pain modulation (e.g. described by the gate control theory of pain). Some fibres project to deeper layers of the spinal grey matter, giving rise to the spinoreticular tract which projects to the ascending reticular activating system (ARAS). Fibres are then relayed to the thalamus and hypothalamus (some fibres reach the thalamus without passing to the ARAS, via the palaeospinothalamic tract).

third-order neurones transmit from the thalamus to the somatosensory cortex.

third-order neurones transmit from the thalamus to the somatosensory cortex.

Pain sensation may thus be modified by ascending or descending pathways at many levels.

Pain, postoperative, see Postoperative analgesia

Palliative care. General approach to care of patients with terminal illness (often malignancy but also neurological, inflammatory, etc.). Recognised as a separate specialty in the UK since 1987. Includes not only symptom control but also psychological, spiritual and social support. Requires a multidisciplinary approach, including the expertise of general physicians, oncologists, surgeons, nursing staff, physiotherapists and religious advisers. Anaesthetists are increasingly involved as they have expertise in controlling symptoms such as pain, anxiety, nausea and vomiting; they also care for patients with terminal disease in the ICU.

See also, Ethics; Euthanasia; Withdrawal of treatment in ICU

Palonosetron. 5-HT3 receptor antagonist licensed as an antiemetic drug in chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting.

Pancreatitis. Acute pancreatitis is an autodigestive process caused by unregulated activation of trypsin in pancreatic acinar cells; this in turn leads to release of other enzymes and activation of complement and kinin pathways. Inflammatory processes also occur with the release of other harmful enzymes. Ischaemic changes, together with generation of free radicals, cause ischaemia and haemorrhagic necrosis of the pancreatic parenchyma. Although the condition is mild in 80% of patients, mortality is high in the remainder because of resulting sepsis, respiratory failure, shock and acute kidney injury.

Associated with biliary tract disease or alcoholism in about 80% of cases. May occasionally follow upper abdominal surgery, pancreatic ductal obstruction (e.g. by carcinoma), trauma, mumps, hepatitis, cystic fibrosis, hypothermia, hypercalcaemia, hyperlipidaemia, diuretics or corticosteroids.

Investigations reveal raised serum and urinary amylase (secondary to leakage from the pancreas), leucocytosis, hyperglycaemia, hypocalcaemia (secondary to calcium sequestration in areas of fat necrosis), hypoproteinaemia and hyperlipidaemia. Since many other disorders also result in increased amylase levels, measurement of the more specific marker serum lipase is increasingly used for diagnosis. Abdominal X-ray may reveal a ‘sentinel loop’ of small bowel overlying the pancreas. CXR may show a raised hemidiaphragm, pleural effusion, atelectasis or acute lung injury. Abdominal CT scanning may be helpful in confirming the diagnosis and assessing the severity of pancreatic damage.

Poor prognosis may be indicated by: age > 55 years; systolic BP < 90 mmHg; white cell count > 15 × 109/l; temperature > 39°C; blood glucose > 10 mmol/l; arterial PO2 < 8 kPa (60 mmHg); plasma urea > 15 mmol/l; serum calcium < 2 mmol/l; haematocrit reduced by over 10%; abnormal liver function tests.

supportive, e.g. O2 therapy, iv fluid administration, electrolyte replacement (especially calcium and magnesium), analgesia, insulin therapy and nutrition (via nasogastric or nasojejunal routes). MODS is treated along conventional lines.

supportive, e.g. O2 therapy, iv fluid administration, electrolyte replacement (especially calcium and magnesium), analgesia, insulin therapy and nutrition (via nasogastric or nasojejunal routes). MODS is treated along conventional lines.

aprotinin, peritoneal lavage, glucagon, calcitonin and somatostatin have been used, but with little evidence of efficacy.

aprotinin, peritoneal lavage, glucagon, calcitonin and somatostatin have been used, but with little evidence of efficacy.

Chronic pancreatitis usually occurs in alcoholics, and is characterised by pancreatic calcification and impaired enzyme secretion with malabsorption, and repeated episodes of pain. Surgery may be required; anaesthetic considerations are related to alcohol abuse, and the consequences of malabsorption and malnutrition.

Frossard JL, Steer ML, Pastor CM (2008). Lancet; 371: 143–52

Pancuronium bromide. Synthetic non-depolarising neuromuscular blocking drug, first used in 1967. Bisquaternary amino-steroid, but with no steroid activity. Initial dose is 0.05–0.1 mg/kg, with tracheal intubation possible after 2–3 min. Effects last 40–60 min. Supplementary dose: 0.01–0.02 mg/kg. Histamine release is extremely rare. May cause increases in heart rate, BP and cardiac output, caused by vagolytic and sympathomimetic actions. The latter may be due to release of noradrenaline from sympathetic nerve endings or blockade of its uptake. Pancuronium is strongly bound to plasma gammaglobulin after iv injection, and metabolised mainly by the kidney but also by the liver. Elimination is delayed in renal and hepatic impairment.

Traditionally used in shocked patients requiring anaesthesia, because of its cardiovascular effects. Formerly commonly used in ICU, but superseded by atracurium and vecuronium.

Pantoprazole sodium. Proton pump inhibitor; actions and effects are similar to those of omeprazole.

Papaveretum. Opioid analgesic drug, first prepared in 1909 and consisting of opium alkaloids: morphine 47.5–52.5%, codeine 2.5–5.0%, noscapine (narcotine) 16–22%, papaverine 2.5–7.0% and others, e.g. thebaine < 1.5%. Widely popular for many years, especially as premedication. In response to a warning issued by the Committee on Safety of Medicines that noscapine may be genotoxic, a new formulation was made available in 1993, consisting of morphine, papaverine and codeine alone. Confusion over dosage regimens has led to many anaesthetists abandoning papaveretum in favour of morphine.

Papaverine. Benzylisoquinoline opium alkaloid, without CNS activity. Used for its relaxant effect on smooth muscle, e.g. GIT and vascular. Has been used to treat cerebral and coronary vasospasm. May be injected iv or applied directly during surgery. Its use has been advocated following intra-arterial injection of thiopental.

Paracelsus (1493–1541). Swiss philosopher and physician; his real name was Theophrastus Bambastus von Hohenheim. Lectured at the University of Basle. Revolutionised the theory of medicine, encouraging the science of research and experimentation. Described the effects of diethyl ether on chickens in 1540 and advocated its use in epilepsy. He is also credited with introducing the use of bellows for ventilating the lungs.

Paracentesis. Puncture of any hollow organ or cavity for removal or instillation of material; however the term usually refers to drainage of ascites from the peritoneum, e.g. in hepatic failure. Removal of large volumes improves cardiac output and respiratory function, decreasing portal venous pressure. It also reduces weight, improving comfort and mobility. However, rapid aspiration may be followed by cardiovascular collapse and oliguria, possibly due to sudden release of the splinting effect of the intra-abdominal fluid.

Paracervical block. Used to provide analgesia during the first stage of labour, or for gynaecological procedures, e.g. dilatation and curettage. First performed in 1926.

With the patient’s legs apart, a special sheathed needle (with tip protected) is directed into the lateral vaginal fornix by the operator’s fingers. The needle tip is advanced 0.5–1 cm to point cranially, laterally and dorsally, and 5–10 ml local anaesthetic agent injected into the parametrial tissue on either side, blocking the uterine nerves that form a plexus at the base of the broad ligament. Vaginal, vulval and perineal sensation is unaffected.

Paracetamol (Acetaminophen). Analgesic drug, derived from para-aminophenol; introduced in the 1950s. Inhibits central prostaglandin synthesis and has a central antipyretic action. Purported to have minimal peripheral anti-inflammatory effects, although this has been disputed. Also inhibits cyclo-oxygenase pathways in the brain, but less so peripherally. Does not cause gastric irritation or affect platelet adhesion. Used in isolation to treat minor pain, and as part of a multimodal strategy for postoperative analgesia.

Rapidly absorbed after oral administration, with peak plasma levels within 60 min. Minimally protein-bound in plasma. Conjugated with glucuronide and sulphate in the liver; < 10% is oxidised by the hepatic P450 system to form N-acetyl-p-benzoquinoneimine, a potential cellular toxin. Normally, this is safely conjugated with glutathione, but it may cause hepatic necrosis in paracetamol poisoning, when the glucuronide and sulphate pathways are saturated and glutathione stores are depleted. Half-life is about 2 h, but its effects last longer.

• Dosage:

0.5–1.0 g orally/rectally 4-hourly, up to 4 g maximum daily.

0.5–1.0 g orally/rectally 4-hourly, up to 4 g maximum daily.

an iv preparation was introduced in the UK in 2004:

an iv preparation was introduced in the UK in 2004:

– adult/child > 50 kg: 1 g 4–6-hourly up to 4 g daily.

– adult/child 10–50 kg: 15 mg/kg 4–6-hourly up to 60 mg/kg daily.

– adult/child < 10 kg: 7.5 mg/kg 4–6-hourly up to 30 mg/kg daily.

Available in combination with other analgesics, e.g. codeine. Over-the-counter sale of 500 mg tablets/capsules in the UK is limited to packs of 32 (packs of 100 tablets/capsules may be purchased from pharmacists in special circumstances).

Paracetamol poisoning. The commonest cause of acute hepatic failure in the UK and USA. Hepatocellular necrosis may occur if >150 mg/kg is taken, due to saturation of the normal metabolic pathways for paracetamol and exhaustion of hepatic glutathione stores. Lower doses may also be toxic, especially in the presence of pre-existing hepatic enzyme induction (e.g. in patients on phenytoin, barbiturates, carbamazepine or rifampicin therapy), or in malnourished, alcoholic or HIV-positive patients.

Patients may be asymptomatic for 24 h after ingestion. Early features include nausea and vomiting, anorexia and right upper quadrant pain. Early impaired consciousness suggests concurrent depressive drug ingestion, e.g. alcohol, opioid analgesic drugs. Liver function tests become abnormal after about 18 h, with prolonged prothrombin time and raised bilirubin at 36–48 h. Hepatotoxicity peaks at about 3–4 days, with hepatic failure if severe. Lactic acidosis, hypoglycaemia and acute kidney injury may also occur. Prognostic factors include the presence of acidaemia (mortality ~95% if pH < 7.3), renal impairment, severe hepatic encephalopathy and a factor V level < 10% (~90% mortality).

as for poisoning and overdoses. Activated charcoal is given if > 150 mg/kg has been ingested and if the patient presents within 1 h of the overdose. Gastric lavage and ipecacuanha are no longer recommended. Ingestion of opioid/paracetamol combinations (e.g. containing codeine, dextropropoxyphene) should be considered if level of consciousness is depressed on presentation, and naloxone given.

as for poisoning and overdoses. Activated charcoal is given if > 150 mg/kg has been ingested and if the patient presents within 1 h of the overdose. Gastric lavage and ipecacuanha are no longer recommended. Ingestion of opioid/paracetamol combinations (e.g. containing codeine, dextropropoxyphene) should be considered if level of consciousness is depressed on presentation, and naloxone given.

replenishment of hepatic glutathione stores with glutathione precursors:

replenishment of hepatic glutathione stores with glutathione precursors:

– N-acetylcysteine: first-line antidote, previously thought to be effective only within 16 h of poisoning, but evidence now also supports later administration. 150 mg/kg is given in 200 ml 5% dextrose iv over 15 min, followed by 50 mg/kg in 500 ml dextrose over 4 h, then 100 mg/kg in 1 litre dextrose over 16 h.

liver transplantation may be required (see Hepatic failure).

liver transplantation may be required (see Hepatic failure).

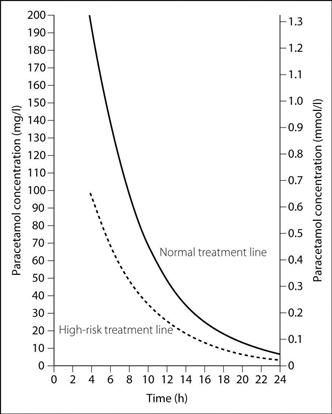

A single measurement of plasma paracetamol concentration taken more than 4 h after ingestion (earlier measurements are unreliable) identifies patients at risk of hepatic damage and thus requiring treatment. Previously, treatment was initiated at different blood levels according to risk factors (Fig. 126); in 2012 the Commission on Human Medicines advised that treatment should be given regardless of risk factors (and if there was doubt over the timing of ingestion).

Paradoxical pain. Type of chronic pain that does not respond to opioid analgesic drugs in the usual way. Usually associated with cancer pain. Increasing the dose may increase side effects without apparent reduction in pain. Altered drug metabolism has been suggested (e.g. for morphine, production of 6-glucuronide [analgesic] reduced in comparison to 3-glucuronide [antanalgesic]), but this has been disputed. Management includes giving the drug by an alternative route, using a different opioid or combination with adjunct drugs such as tricyclic antidepressant drugs.

Paraesthesia. Abnormal positive sensation similar to ‘pins and needles’, occurring when neural tissue is irritated (e.g. peripheral nerve, spinal cord, sensory cerebral cortex). May be produced accidentally or intentionally during regional anaesthesia. Elicitation of paraesthesia may increase the chances of successful nerve block but also of neurological damage.

Paraldehyde. Obsolete hypnotic and anticonvulsant drug, introduced in 1882. Has an offensive smell, and is irritant and flammable. Decomposes with heat and light to acetic acid, and dissolves plastic. Has been used in the treatment of psychiatric disturbance, status epilepticus and for premedication.

Paralysis, acute. May result in paraplegia (diplegia) with paralysis of the legs and lower part of the trunk or quadriplegia (tetraplegia) with paralysis of all four limbs and trunk. The suffix ‘plegia’ denotes complete paralysis; ‘paresis’ denotes partial paralysis. ‘Hemiplegia’ refers to unilateral paralysis, e.g. associated with CVA and other neurovascular conditions including migraine.

• May be caused by lesions affecting the:

– neoplastic, e.g. frontal lobe or brainstem tumours.

– vascular, e.g. bilateral carotid or basilar artery thrombosis.

– demyelinating disease, e.g. multiple sclerosis, central pontine myelinosis.

– hydrocephalus, cerebral palsy.

– neoplastic (primary or metastatic).

– vascular, e.g. arteriovenous malformations, anterior spinal artery thrombosis, epidural haematoma.

– inflammatory, e.g. transverse myelitis, multiple sclerosis.

– infectious, e.g. viral myelitis (e.g. herpes, poliomyelitis, HIV infection), epidural abscess, syphilis, TB.

– degenerative, e.g. motor neurone disease, bone disease affecting the spinal column.

– nutritional, e.g. vitamin B12 and E deficiency.

– hereditary, e.g. Friedreich’s ataxia.

– inflammatory, e.g. Guillain–Barré syndrome, diphtheria.

– metabolic, e.g. acute intermittent porphyria.

– poisoning, e.g. heavy metal poisoning.

– poisoning, e.g. botulism, organophosphorus poisoning, aquatic toxins (e.g. tetrodotoxin).

– bites and stings, e.g. snakes.

– immunological, e.g. myasthenia gravis, myasthenic syndrome.

– inflammatory, e.g. polymyositis.

– congenital, e.g. periodic paralysis.

– electrolyte imbalance, e.g. hypo/hyperkalaemia, hypercalcaemia, hypermagnesaemia, hypophosphataemia.

Diagnosis is based largely on history, examination and investigations (e.g. MRI, CSF examination, nerve conduction studies). The commonest cause of acute paralysis is Guillain–Barré syndrome followed by spinal cord injury caused by fracture dislocation of the cervical spine. Thoracic and lumbar spine damage is less common but may also cause paraplegia. In the absence of trauma, vascular insult to the spinal cord may produce paralysis that may be sudden or evolve over several hours. This usually follows thrombosis of a spinal segmental artery and results in the anterior spinal artery syndrome. Spinal subarachnoid haemorrhage similarly causes rapid paralysis, as will basilar thrombosis causing pontine infarction. Peripheral causes usually produce subacute paralysis, with the exception of periodic paralysis (may occur over minutes).

• Anaesthetic/ICU implications:

respiratory failure requiring ventilatory support, e.g. IPPV; this may be exacerbated by aspiration of gastric contents if the pharyngeal and laryngeal muscles are affected. Support is likely to be required for a long time since most conditions resolve slowly.

respiratory failure requiring ventilatory support, e.g. IPPV; this may be exacerbated by aspiration of gastric contents if the pharyngeal and laryngeal muscles are affected. Support is likely to be required for a long time since most conditions resolve slowly.

control of the airway: suxamethonium may cause severe hyperkalaemia depending on the age of the lesion or whether the process is ongoing. Alternative methods include use of rapidly acting non-depolarising drugs, e.g. rocuronium, awake intubation, tracheostomy. The latter is often used in the long term.

control of the airway: suxamethonium may cause severe hyperkalaemia depending on the age of the lesion or whether the process is ongoing. Alternative methods include use of rapidly acting non-depolarising drugs, e.g. rocuronium, awake intubation, tracheostomy. The latter is often used in the long term.

there may also be autonomic disturbance depending on the cause.

there may also be autonomic disturbance depending on the cause.

other features of the primary disease.

other features of the primary disease.

long-term supportive care includes nutrition and fluid balance, regular turning and prevention of decubitus ulcers, prophylaxis against DVT and nosocomial infection, prompt treatment of infection and psychological support.

long-term supportive care includes nutrition and fluid balance, regular turning and prevention of decubitus ulcers, prophylaxis against DVT and nosocomial infection, prompt treatment of infection and psychological support.

Paramagnetic oxygen analysis, see Oxygen measurement

Parametric tests, see Data; Statistical tests

Paraplegia, see Paralysis, acute

corrosive burns to mouth, pharynx and oesophagus.

corrosive burns to mouth, pharynx and oesophagus.

dyspnoea, pulmonary oedema, acute lung injury, rapidly progressive pulmonary fibrosis. Lung damage is exacerbated by high inspired O2 concentrations.

dyspnoea, pulmonary oedema, acute lung injury, rapidly progressive pulmonary fibrosis. Lung damage is exacerbated by high inspired O2 concentrations.

cardiac, hepatic and renal impairment.

cardiac, hepatic and renal impairment.

general support as for poisoning and overdoses.

general support as for poisoning and overdoses.

oral administration or gastric instillation of an adsorbent such as activated charcoal 100 g followed by 50 g 4-hourly, or fuller’s earth 1000 ml 15% aqueous suspension (or 500 ml 30%) 2-hourly, together with 200 ml 20% mannitol or magnesium sulphate as a laxative; administration is repeated until the charcoal or fuller’s earth is seen in the stool. Gastric lavage is not recommended.

oral administration or gastric instillation of an adsorbent such as activated charcoal 100 g followed by 50 g 4-hourly, or fuller’s earth 1000 ml 15% aqueous suspension (or 500 ml 30%) 2-hourly, together with 200 ml 20% mannitol or magnesium sulphate as a laxative; administration is repeated until the charcoal or fuller’s earth is seen in the stool. Gastric lavage is not recommended.

haemoperfusion has been advocated but paraquat’s large volume of distribution limits its usefulness.

haemoperfusion has been advocated but paraquat’s large volume of distribution limits its usefulness.

Paraquat concentrations can be measured in the serum or (more easily) in the urine.

Garawammana IB, Buckley NA (2011). Br J Clin Pharmacol; 72: 745–57

Parasympathetic nervous system. Part of the autonomic nervous system. Myelinated preganglionic efferent fibres emerge with cranial nerves III, VII, IX and X, and spinal nerves S2–4. They pass to their target organs, where they synapse with short non-myelinated postganglionic fibres (cf. sympathetic nervous system). The vagus nerves carry about 75% of all parasympathetic fibres and innervate the heart, lungs, oesophagus, stomach, other viscera and GIT as far as the splenic flexure. The sacral nerves run as the pelvic splanchnic nerves to the pelvic viscera (see Fig. 21; Autonomic nervous system). Afferent fibres travel in cranial nerves IX and X and in the sacral nerves.

• Effects of parasympathetic stimulation:

pupillary and ciliary muscle contraction, increased lacrimal secretion.

pupillary and ciliary muscle contraction, increased lacrimal secretion.

bronchoconstriction and increased secretions.

bronchoconstriction and increased secretions.

increased GIT motility, relaxation of sphincters and increased secretions (profuse watery secretion from salivary glands). Increased insulin and glucagon secretion.

increased GIT motility, relaxation of sphincters and increased secretions (profuse watery secretion from salivary glands). Increased insulin and glucagon secretion.

bladder contraction and relaxation of sphincter.

bladder contraction and relaxation of sphincter.

Acetylcholine is the neurotransmitter at all synapses. Its actions are divided into nicotinic (at ganglia) and muscarinic (at postganglionic synapses).

Parasympathomimetic drugs. Drugs producing the effects of stimulation of the parasympathetic nervous system. Include:

drugs that stimulate acetylcholine receptors:

drugs that stimulate acetylcholine receptors:

– acetylcholine: has widespread actions, therefore not used therapeutically.

– synthetic choline esters, e.g. carbachol, methacholine: the former has nicotinic and muscarinic actions, the latter mainly muscarinic. Both are resistant to hydrolysis by cholinesterases. Carbachol is used in glaucoma and urinary retention. Bethanechol is a similar drug, and used in urinary retention and as a laxative.

– cholinomimetic alkaloids, e.g. pilocarpine: used in glaucoma.

Paravertebral block. Blocks nerves as they pass through the intervertebral foramina into the paravertebral space; may be performed in the thoracic or lumbar region, e.g. for breast or abdominal surgery respectively. Solution may track medially through the foramina into the epidural space, or laterally into the intercostal space.

With the patient sitting or in the lateral position, a skin wheal is raised 3–5 cm lateral to the most cephalad aspect of the appropriate spinous processes. An 8 cm needle is inserted approximately 3–4 cm perpendicular to the skin until the transverse process is encountered, then walked off the cephalad border and advanced a further 1–2 cm. 5 ml local anaesthetic agent is then injected. May be performed bilaterally.

A loss-of-resistance technique may be used to confirm correct needle placement, as for epidural anaesthesia. A catheter may be passed into the paravertebral space for prolonged analgesia. Complications include epidural, subarachnoid and iv injection.

Thavaneswaran P, Rudkin GE, Cooter RD, et al. (2010). Anesth Analg; 110: 1740–4

Parecoxib. NSAID acting preferentially on cyclo-oxygenase-2, licensed for short-term (< 2 days) treatment of postoperative pain. Onset of action is 7–13 min, with effects lasting up to 12 h. A prodrug of valdecoxib, to which it is rapidly converted (half-life 22 min); valdecoxib itself has a half-life of 8 h.

Parenteral nutrition, see Nutrition, total parenteral

Parkinsonism, see Parkinson’s disease

Parkinson’s disease. Idiopathic degenerative disorder of the CNS involving the basal ganglia and extrapyramidal motor system, with loss of dopamine leading to an imbalance between acetylcholine and dopamine in the substantia nigra. Secondary causes include carbon monoxide poisoning, encephalitis, CVA, heavy metal poisoning, or drugs that antagonise dopamine receptors (e.g. phenothiazines); secondary disease is termed ‘parkinsonism’. Affects 3% of the population > 65 years old; the aetiology is in most cases unknown but may include genetic, toxic and environmental factors.

upper airway and vocal cord dysfunction can result in laryngospasm.

upper airway and vocal cord dysfunction can result in laryngospasm.

a restrictive ventilatory defect may occur.

a restrictive ventilatory defect may occur.

• Treatment is aimed at restoring the dopaminergic/cholinergic balance, and includes:

increasing brain levels of dopamine by administering its precursor levodopa (dopamine does not cross the blood–brain barrier). Conversion of levodopa to dopamine outside the CNS with resultant side effects is prevented by concurrent administration of carbidopa or benserazide. These inhibit dopa decarboxylase peripherally, as they do not cross into the brain. Bradykinesia and rigidity are improved more than tremor. Side effects include involuntary movements, nausea, vomiting, and psychiatric disturbances. Improvement may be intermittent (on–off effect).

increasing brain levels of dopamine by administering its precursor levodopa (dopamine does not cross the blood–brain barrier). Conversion of levodopa to dopamine outside the CNS with resultant side effects is prevented by concurrent administration of carbidopa or benserazide. These inhibit dopa decarboxylase peripherally, as they do not cross into the brain. Bradykinesia and rigidity are improved more than tremor. Side effects include involuntary movements, nausea, vomiting, and psychiatric disturbances. Improvement may be intermittent (on–off effect).

anticholinergic drugs: benzatropine, trihexyphenidyl (benzhexol), orphenadrine: improve tremor and rigidity more than bradykinesia.

anticholinergic drugs: benzatropine, trihexyphenidyl (benzhexol), orphenadrine: improve tremor and rigidity more than bradykinesia.

other drugs: bromocriptine, apomorphine and lisuride (dopamine agonists), selegiline (type B monoamine oxidase inhibitor), amantadine, pergolide.

other drugs: bromocriptine, apomorphine and lisuride (dopamine agonists), selegiline (type B monoamine oxidase inhibitor), amantadine, pergolide.

levodopa is continued up to surgery, since its half-life is short. It has been given iv.

levodopa is continued up to surgery, since its half-life is short. It has been given iv.

symptoms may be exacerbated by dopamine antagonists, e.g. phenothiazines and butyrophenones (including antiemetic drugs).

symptoms may be exacerbated by dopamine antagonists, e.g. phenothiazines and butyrophenones (including antiemetic drugs).

the risk of hyperkalaemia following suxamethonium is controversial.

the risk of hyperkalaemia following suxamethonium is controversial.

postoperative sleep apnoea has been reported, especially in the postencephalitic disease.

postoperative sleep apnoea has been reported, especially in the postencephalitic disease.

[James Parkinson (1755–1824), London physician]

Kalenka A, Schwarz A (2009). Curr Opin Anaesthesiol; 22: 419–24

Paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria. Rare acquired chronic haemolytic anaemia, resulting from blood cell membrane abnormality and increased sensitivity to lysis by complement. Haemoglobinuria is classically noticed on waking.

Haemolysis may be precipitated by infection, hypoxaemia, hypercapnia, acidosis and hypoperfusion, all of which should be avoided during anaesthesia. Steroids may help reduce haemolysis. Platelet destruction may lead to bleeding, or abnormal function may lead to venous thrombosis. Renal impairment is common. Drugs causing complement activation should be avoided, and red blood cells washed before blood transfusion.

Kathirvel S, Prakash A, Lokesh N, Sujatha P (2000). Anesth Analg; 91: 1029–31

PART team. Patient-at-risk team, see Outreach team

Partial liquid ventilation, see Liquid ventilation

Partial pressure. Pressure exerted by each component of a gas mixture. For a gas dissolved in a liquid (e.g. blood) the term ‘tension’ is used, although denoted by the same symbol (P).

Partial thromboplastin time, see Coagulation studies

Partition coefficient. Ratio of the amount of substance in one phase to the amount in another phase at stated temperature, with the two phases being of equal volume and in equilibrium with each other. Depends on the relative solubility of the substance in the two phases. May refer to solids, liquids or gases; when the phases are liquid and gas it equals the Ostwald solubility coefficient. Blood/gas and oil/gas partition coefficients of inhalational anaesthetic agents are related to speed of uptake and potency respectively.

Pascal. SI unit of pressure. 1 pascal (Pa) = 1 N/m2.

Pasteur point. Critical mitochondrial PO2 below which aerobic metabolism cannot occur. Thought to be 0.15–0.3 kPa (1.4–2.3 mmHg).

[Louis Pasteur (1822–1895), French scientist and microbiologist]

Patent ductus arteriosus, see Ductus arteriosus, patent

Patient-at-risk team, see Outreach team

Patient-controlled analgesia (PCA). Technique whereby intermittent boluses of analgesic drugs (e.g. opioid analgesic drugs) are self-administered by patients according to their own requirements, used widely for postoperative analgesia. Usually iv but other routes include epidural, sc and intranasal. Systems usually consist of infusion devices that deliver on-demand bolus injections, with or without a continuous background infusion. Bolus volume and rate and the minimum time between boluses (lockout interval) may be altered. These controls must be inaccessible to the patient (or relatives), and the infusion connected downstream from a non-return valve if attached to another iv infusion (to prevent retrograde flow into the second infusion set with subsequent overdosage when the latter is flushed).

Drugs with relatively short half-lives are usually employed. Widely varying dosage regimens have been described; individual adjustment may be required (Table 36). Complications are related to incorrect programming and setting-up, patients’ misunderstanding of the technique, equipment malfunction and administration of additional conventional ‘on demand’ opioid analgesia leading to overdose. Patients require adequate monitoring, since respiratory depression may still occur. Nausea and vomiting may be a problem if regular antiemetics are not prescribed, firstly because drug levels remain constant, and secondly because the ‘as required’ antiemetics that would be routinely given along with im opioids tend not to be given if ‘as required’ opioids themselves are no longer being given. PCA is also used (epidural and iv) for analgesia in labour (see Obstetric analgesia and anaesthesia).

Grass JA (2005). Anesth Analg; 101 (Suppl): S44–61

Table 36 Dosage regimens for different opioids for iv patient-controlled analgesia

| Drug | Bolus dose (mg) | Lock-out interval (min) |

| Diamorphine | 0.5–1.5 | 3–5 |

| Fentanyl | 0.02–0.05 | 3–10 |

| Morphine | 0.5–2.0 | 5–15 |

| Nalbuphine | 1–5 | 5–15 |

| Oxycodone | 0.5–2.0 | 5–10 |

| Pethidine | 5–20 | 5–15 |

Peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR). Maximal rate of air flow during a sudden forced expiration. Most conveniently measured with a peak flowmeter; may also be measured from a flow–volume loop, or with a pneumotachograph. Highly dependent on patient effort. Reduced by obstructive airways disease, e.g. asthma, COPD. Normal values: 450–700 l/min (males), 250–500 l/min (females).

Peak flowmeters. Simple and inexpensive hand-held flowmeters for measuring peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR). The Wright peak flowmeter is a constant-pressure, variable orifice device, able to measure peak flow rates of up to 1000 l/min. It has a flat circular body, with a handle and mouthpiece. Exhaled air is directed by a fixed baffle within the body on to a movable vane that is free to rotate around a central axle against the force of a small spring. There is a circular slot in the base of the chamber, through which expired air escapes. As the vane moves, the slot is uncovered, thus increasing the effective orifice size. The vane reaches its furthest excursion according to PEFR, and is held there by a ratchet. PEFR is read from a dial on the face of the meter, according to a pointer attached to the vane. It slightly underreads in comparison with a pneumotachograph.

PEFR, see Peak expiratory flow rate

Pelvic trauma. Usually caused by blunt trauma (e.g. road accidents or falls) and often associated with abdominal trauma, chest trauma and head injuries.

pelvic ring: disruption causes pain on movement. Diagnosis is confirmed with X-ray or CT scanning.

pelvic ring: disruption causes pain on movement. Diagnosis is confirmed with X-ray or CT scanning.

vaginal and bowel perforation from bony fragments.

vaginal and bowel perforation from bony fragments.

pelvic blood vessels: arteriography may be necessary for diagnosis.

pelvic blood vessels: arteriography may be necessary for diagnosis.

resuscitation as for trauma generally.

resuscitation as for trauma generally.

intraperitoneal bladder rupture requires laparotomy and drainage of the bladder with both suprapubic and urethral catheters. Extraperitoneal rupture requires drainage via a urethral catheter with subsequent confirmation of healing using cystography. Broad-spectrum antibacterial drugs should be given.

intraperitoneal bladder rupture requires laparotomy and drainage of the bladder with both suprapubic and urethral catheters. Extraperitoneal rupture requires drainage via a urethral catheter with subsequent confirmation of healing using cystography. Broad-spectrum antibacterial drugs should be given.

pelvic vessels may require embolisation if haemorrhage is severe.

pelvic vessels may require embolisation if haemorrhage is severe.

Pendelluft. Phenomenon originally believed to cause the hypoxaemia occurring in flail chest. The theory suggested that air is drawn from the affected side into the unaffected lung during inspiration, due to disrupted chest wall integrity on the damaged side. During expiration, air passes from the normal lung back into the affected lung; thus air moves to and fro between the two sides, instead of in and out of the chest via the trachea. Hypoventilation and  mismatch due to pain, lung contusion and sputum retention are now thought to be more important.

mismatch due to pain, lung contusion and sputum retention are now thought to be more important.

Penicillamine. Degradation product of penicillin used as a chelating agent, especially in copper, lead, gold, mercury and zinc poisoning. Also used in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and chronic active hepatitis.

• Side effects: blood dyscrasias, convulsions, neuropathy, nausea and vomiting, colitis, renal and hepatic impairment, bronchospasm, myasthenia gravis, systemic lupus erythematosus-like syndrome, rashes. Blood counts and urine testing for proteinuria should be performed regularly.

Penicillins. Group of natural and synthetic bactericidal antibacterial drugs with a β-lactam structure. Act by interfering with formation of peptidoglycan cross-links within the bacterial cell wall, resulting in osmotic damage. Penetrate body tissue and fluids well except for the CNS (unless the meninges are inflamed). Excreted renally by active tubular secretion. Bacterial resistance is caused by production of β-lactamases that hydrolyse the β-lactam ring.

Penile block. Used to provide peri- and postoperative analgesia for circumcision and other procedures on the penis, especially in children.

A needle is introduced at right angles through a skin wheal in front of the symphysis, and passed below its caudal edge. It is inserted up to 3–5 mm deeper than the symphysis (a click may be felt). After negative aspiration for blood, 1–2 ml local anaesthetic agent is injected for children up to 3 years old, 3–5 ml for older children and 5–10 ml for adults. Adrenaline may cause ischaemia and necrosis and must not be used. Solution diffuses to block both sides following midline injection, but risk of haematoma is greater; therefore two injections may be performed, one either side of the midline. 1–5 ml solution is also injected around the base of the penis.

Pentamidine isetionate. Antiprotozoal agent used in the treatment and prophylaxis of pneumocystis pneumonia. Because of its side effects, used as a second-line drug if infection is resistant to co-trimoxazole. Has also been used to treat leishmaniasis and trypanosomiasis.

Pentastarch, see Hydroxyethyl starch

Pentazocine hydrochloride/lactate. Agonist–antagonist opioid analgesic drug described in 1962. Benzomorphan derivative, with agonist activity at kappa and sigma opioid receptors, and antagonist activity at mu receptors. Used for moderate to severe pain; has been used to reverse the respiratory depression caused by morphine or fentanyl whilst maintaining analgesia.

Undergoes extensive first-pass metabolism; conjugated with glucuronides and excreted renally. Half-life is about 2–3 h.

• Dosage: 0.5–1.0 mg/kg, iv/im/sc. 50–100 mg orally, 3–4-hourly.

hallucinations and dysphoria, especially in the elderly.

hallucinations and dysphoria, especially in the elderly.

Pentolinium tartrate. Obsolete long-acting ganglion blocking drug used to treat hypertension and in hypotensive anaesthesia.

Pentoxifylline (Oxpentifylline). Xanthine used in peripheral vascular disease and vascular dementia. Reduces blood viscosity. Also inhibits tumour necrosis factor production by macrophages; has thus been studied as a potential therapeutic agent in sepsis.

Peptic ulcer disease. Ulceration due to an imbalance between the action of gastric acid and the normal protective mechanisms of the upper GIT mucosa. May occur at any site exposed to gastric acid, e.g. oesophagus, stomach, duodenum. Abnormal gastric emptying, gastro-oesophageal reflux, drugs (e.g. NSAIDs, corticosteroids), alcohol, psychological and epidemiological factors are thought to contribute. Infection with Helicobacter pylori has a fundamental role in the development of chronic gastritis and peptic ulcer disease; the persistence of serum antibodies against the organism reflects the chronicity of the infection. About 70% of patients with gastric ulcers have evidence of H. pylori infection that can be detected with the 13C-urea breath test. Infected patients have an increased rate of GIT bleeding in the ICU.

neutralisation of existing acid with antacids.

neutralisation of existing acid with antacids.

increased surface protection (postulated mechanism):

increased surface protection (postulated mechanism):

– anticholinergic drugs, e.g. pirenzepine.

– eradication of H. pylori infection. Recommended therapy includes PAC regimen (double dose proton pump inhibitor, amoxicillin, clarithromycin) or PCM regimen (amoxicillin is replaced by metronidazole) for 1 week. Effective in < 90%.

surgery: indications include failed medical treatment, malignant change, or complications as above. Surgery may involve highly selective vagotomy or vagotomy and drainage procedure (duodenal ulcer), or partial gastrectomy (gastric ulcer). Anaesthesia in chronic disease requires no special precautions unless gastro-oesophageal reflux or anaemia is present. Acute haemorrhage or perforation may present with vomiting, shock and hypovolaemia.

surgery: indications include failed medical treatment, malignant change, or complications as above. Surgery may involve highly selective vagotomy or vagotomy and drainage procedure (duodenal ulcer), or partial gastrectomy (gastric ulcer). Anaesthesia in chronic disease requires no special precautions unless gastro-oesophageal reflux or anaemia is present. Acute haemorrhage or perforation may present with vomiting, shock and hypovolaemia.

Percentile. Value that indicates the percentage of a distribution equal to or below it; e.g. 97% of measurements are equal or less than the 97th percentile. Often used in charts, e.g. of children’s height against age. The 3rd, 50th and 97th percentiles plotted on the chart indicate the heights that include 3%, 50% and 97% of the population respectively, at each age. May thus be used to follow a child’s growth, since height would be expected to remain within the same percentile during normal development. The 3rd and 97th percentiles approximate to ± 2 standard deviations from the mean, for normally distributed data.

Often used to indicate variability (scatter) around the median for ordinal data.

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Group of percutaneous endovascular techniques for treating ischaemic heart disease. Considerably cheaper than surgical coronary artery bypass graft (CABG), with a similar risk of death and MI in selected patients; CABG is more effective at relieving angina and less likely to require repeat intervention, but carries higher procedural risk of CVA.

adult dose.

adult dose. adult dose.

adult dose. adult dose.

adult dose. adult dose.

adult dose. adult dose.

adult dose.