Chapter 2 Ovulation and the menstrual cycle

Disturbances occurring during the menstrual cycle are discussed in Chapters 28 and 29.

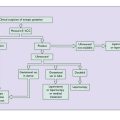

MENARCHE

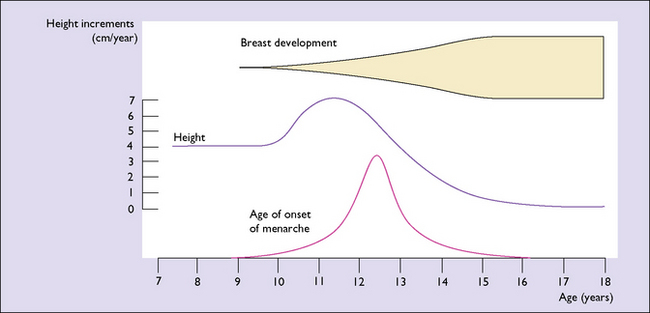

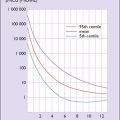

The underlying major endocrinological change is that the hypothalamus begins to secrete releasing hormones. These lead to the release into the circulation of adrenal androgens and pituitary human growth hormone (hGH). It is hGH that causes the growth spurt which begins 3–4 years before the menarche, and which is maximal in the first 2 years (Fig. 2.1). The physical growth slows down as the first menstruation (menarche) approaches. This is because increasing quantities of oestrogen are secreted by the ovaries and feed back negatively, reducing hGH secretion. Shortly after the secretion of hGH starts, the hypothalamus begins to release gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) in an episodic pulsed manner. At first, the pulses are greater in amplitude during sleep, but after 2 years they occur by day and night at about 2-hour intervals. GnRH induces the release of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) from the pituitary gland, which in turn bind to receptors in the ovaries and induce the secretion and release of oestrogen and progesterone into the circulation. The quantity of FSH and LH increases as the girl matures.

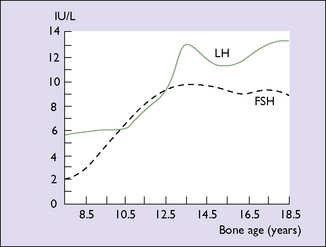

Until the age of 8 years, only small quantities of oestrogen are secreted (and less of progesterone). After that age oestrogen secretion begins to rise, slowly at first, but after the age of about 11 years the rise is quite rapid. The FSH levels reach a plateau when the girl is aged about 13. LH levels rise more slowly until 1 year before menarche, at which time a rapid rise occurs (Fig. 2.2). By this time, the GnRH pulses occur every 90 minutes. These hormonal changes persist until after the age of 40, when changes presaging the menopause begin (see Ch. 42).

EFFECTS OF OESTROGEN AND PROGESTERONE ON BODY TISSUES

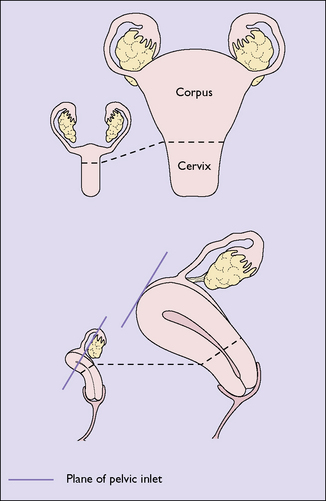

Oestradiol stimulates the growth of the vulva and the vagina after the menarche, the hormone causing proliferation of both the epithelial and the muscular layers. This oestrogen also stimulates the formation of more blood vessels, which supply the organs. The uterus is particularly stimulated by oestradiol, which increases its vascularity. Oestradiol causes endometrial proliferation, stimulating the growth of the glands and stroma as well as the growth of the muscular layers of the uterus, so that the uterus grows from its prepubertal size to its adult size in the perimenarchal years (Fig. 2.3). The great increase in circulating oestrogen in pregnancy causes the rapid growth of the uterus, and the lack of this hormone after the menopause leads to uterine atrophy.

MENSTRUATION AND OVULATION

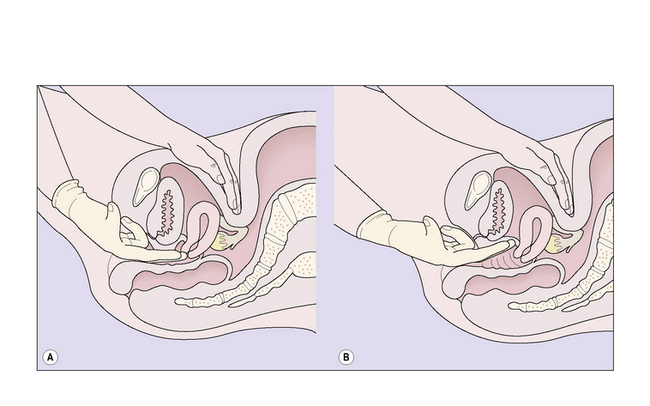

The endocrinological effect of the rising levels of oestradiol is that it exerts a negative feedback on the anterior pituitary and the hypothalamus, with the result that the secretion of FSH falls whereas that of oestradiol rises to a peak (Fig. 2.4). Some 24 hours later a sudden large surge of LH and a smaller surge of FSH occur. This positive feedback leads to the release of an ovum from the largest follicle. Ovulation has occurred. (If large amounts of FSH are produced by the anterior pituitary gland, or usually if FSH injections are given, superovulation occurs, seven or more follicles reaching maturity, a technique used in in-vitro fertilization.)

The collapse of the follicle from which the ovum has been released leads to a change in its nature. The theca granulosa cells proliferate, become yellow in colour (luteinized) and are referred to as theca-lutein cells. The collapsed follicle becomes a corpus luteum. The lutein cells of the corpus luteum secrete progesterone as well as oestrogen. Progesterone secretion reaches a plateau about 4 days after ovulation and then rises progressively should the fertilized ovum implant into the endometrium. The trophoblastic cells of the implanted embryo immediately secrete hCG, which maintains the corpus luteum so that the secretion of oestradiol and progesterone continues. On the other hand, if pregnancy fails to occur the theca-lutein cells degenerate and produce less oestradiol and progesterone. This reduces the negative feedback on the gonadotrophs, with a rise in the secretion of FSH. The falling circulating levels of oestradiol (Table 2.1) and progesterone cause changes in the endometrium (see p. 14), which leads to menstruation.

Table 2.1 Plasma oestradiol levels during the menstrual cycle

| Plasma Oestradiol (pmol/L) | |

|---|---|

| Early follicular phase | 75–600 |

| Late follicular phase | 110–1500 |

| Periovulatory peak | 170–1000 |

| Early and mid-luteal phase | 75–1000 |

| Late luteal phase | 10–900 |

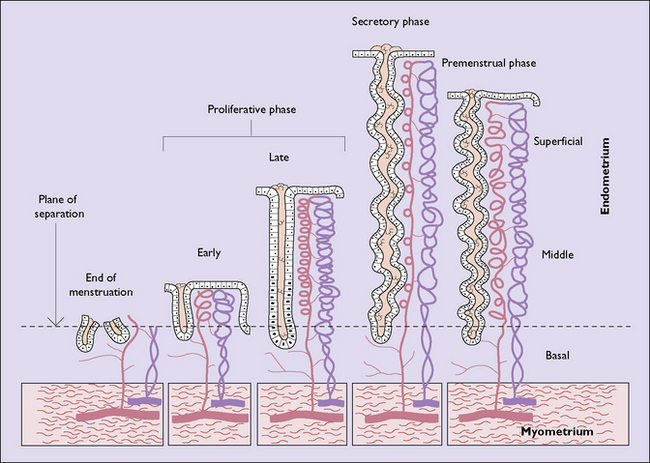

ENDOMETRIAL CYCLE

Menstruation is the periodic discharge from the uterus of blood, tissue fluid and endometrial cellular debris, in varying amounts. The quantity of tissue fluid is the greatest variable. This means that some women who complain of heavy periods do not become anaemic as might be expected (see Ch. 28). The mean blood loss during menstruation is 30 mL (range 10–80 mL). Menstruation normally occurs at intervals of 22–35 days (counted from day 1 of the menstrual flow to day 1 of the next) and the menstrual discharge lasts from 1 to 8 days.

Proliferative phase

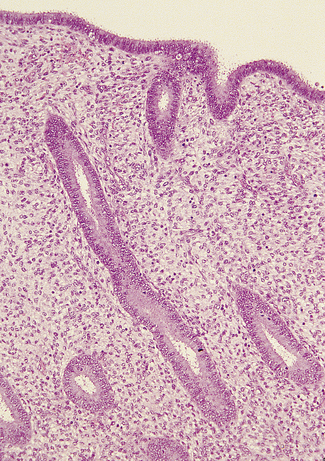

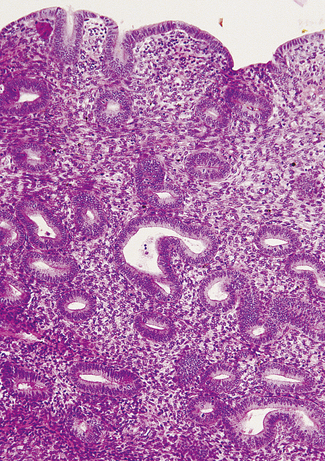

In the early proliferative phase the endometrium is thin, the glands few, narrow, straight, and lined with cuboidal cells, and the stroma is compact (Fig. 2.5). The early regenerative phase lasts from day 3 of the menstrual cycle to day 7, when proliferation speeds up. The epithelial glands increase in size and grow down perpendicular to the surface. Their cells become columnar with basal nuclei. The stromal cells proliferate, remaining compact and spindle shaped (Fig. 2.6). Mitoses are common in glands and stroma. The endometrium is supplied by basal arteries in the myometrium which send off branches at right angles to supply the endometrium. At first, as each artery penetrates the basal endometrium it is straight, but in the middle and superficial layers it becomes spiral. This coiling permits the artery to supply the growing endometrium by becoming uncoiled. Each spiral artery supplies a defined area of endometrium.

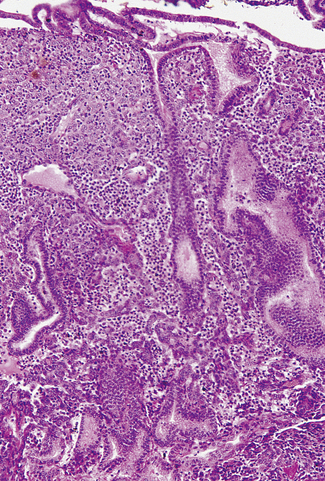

Luteal phase

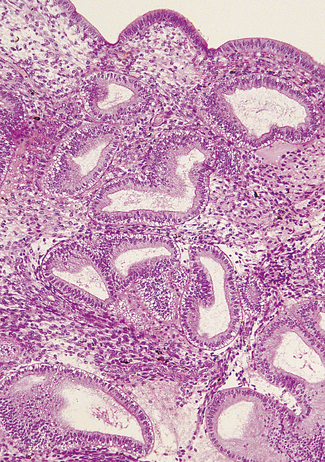

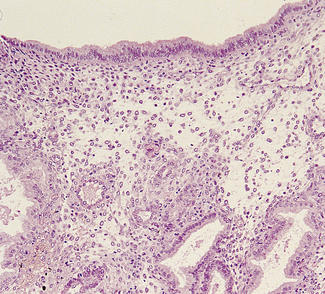

If ovulation occurs, as is usual except at the extremes of the reproductive years, the endometrium undergoes marked changes. The changes start in the last 2 days of the proliferative phase, but increase dramatically after ovulation. Secretory vacuoles, rich in glands, appear in the cells lining the endometrial glands. At first the vacuoles are basal and displace the cell’s nucleus superficially (Fig. 2.7). They rapidly increase in number and the glands become tortuous. By the sixth day after ovulation the secretory phase is at its peak. The vacuoles have streamed past the nucleus. Some have discharged mucus into the cavity of the gland; others are full of mucus, leading to a saw-toothed appearance (Fig. 2.8). The spiral arteries increase in length by uncoiling (Fig. 2.9).

Menstrual phase

During menstruation the superficial and middle layers of the endometrium are shed, the deep basal layer being spared (Fig. 2.10). The shedding occurs in an irregular, haphazard manner, some areas being unaffected and others undergoing repair, while simultaneously other areas are being shed. The shed endometrium, with tissue fluid and blood, forms a coagulum in the uterine cavity. This is immediately liquefied by fibrinolysins and the liquid, which does not coagulate, is discharged through the cervix by uterine contractions. If the quantity of blood lost in the process is considerable, there may be insufficient fibrinolysins and clots are expelled through the cervix.

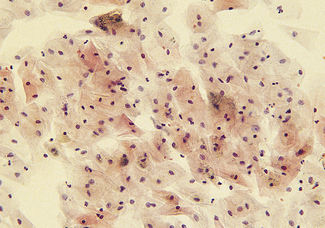

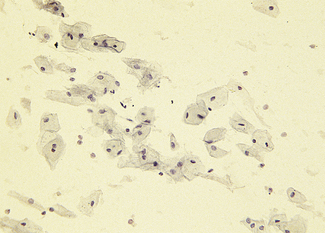

VAGINAL CYCLE

Cyclic changes occur in the vaginal epithelium which are dependent on the ratio between oestrogen and progesterone. In the follicular phase, superficial and large intermediate cells predominate. As ovulation approaches the proportion of superficial cells increases and few leucocytes can be seen (Fig. 2.11). Following ovulation a marked change occurs as progesterone is secreted. The superficial cells are replaced by intermediate cells and leucocytes increase in number, causing the smear to look dirty (Fig. 2.12).