2 Overview of surgery

This chapter reviews conditions and generic problems common to all surgical specialties.

Wound healing and management

Understanding the principles of wound healing and management is essential in all forms of surgery. Careful wound management reduces complications such as wound breakdown, infection and poor cosmetic result. Oxygen is the crucial ingredient for wound healing. Adequate oxygen delivery depends on heart and lung function, haemoglobin level and blood supply to the wounded tissue. Box 2.1 highlights local and systemic factors affecting wound healing. These same factors apply whether the healing wound is of skin, bone or any other tissue, e.g. a bowel anastomosis.

Classification of surgical wounds

Management of bleeding (haemostasis)

Wound closure

Wound closure can be achieved in a number of ways:

• plastic surgery procedures to close defects which cannot be treated with the above methods, e.g. skin grafting, flap transfer.

Blood products

• Whole blood is rarely used, as blood is a very scarce commodity. Specific use of the required component is a more effective use of these products. Packed red cells are used for acute haemorrhage in combination with colloid or crystalloid solutions and correction of anaemia after the diagnosis has been established. Platelets may be given to prevent bleeding, whilst FFP is given often in severe coagulopathy states, e.g. leaking aortic aneurysm surgery.

• Cryoprecipitate contains fibrinogen, factor VIIIc and von Willebrand factor. Its use is confined in surgery to patients with severe coagulopathy, e.g. severe sepsis.

• Albumin may be used for correction of hypoalbuminaemic states.

• Immunoglobulins are used to prevent infection in patients with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura and specific immunoglobulins may be used for patients who have contracted infections, e.g. antihepatitis B immunoglobulin. Consultation with a haematologist is mandatory in situations where these products are needed. Protocols for massive transfusion exist in all UK hospitals.

Blood groups

Most hospitals now have strict guidelines for the use and ordering of blood for operations and with new technology blood can be available within 20–30 minutes of a request even if the blood is not ‘grouped and saved’. The blood transfusion checking procedure is shown in Box 2.2.

Box 2.2

Blood transfusion checking procedure

Blood must be checked by two nurses, one of whom is a registered nurse, before transfusion

Check the blood bag is not leaking or wet and has a compatibility label attached

Check the patient’s surname, first names, sex, date of birth, hospital number on

Check the expiry date of the unit of blood on

Check the blood group and unit number on

(from Ballinger & Patchett 2003 Pocket Essentials of Clinical Medicine, 3rd edn, Saunders, Edinburgh, with permission)

Blood transfusion

Blood transfusion is not without risk. Other therapies must always be considered before prescribing a blood transfusion, e.g. plasma substitutes or iron therapy. The introduction of screening programmes for hepatitis B and C and HIV have now made transfusion safer. For the first 48 hours after transfusion, donated blood does not have the same oxygen-carrying capacity as normal blood due to red blood cell depletion of 2,3-biphosphoglycerate (2,3-BPG), which shifts the oxygen-haemoglobin dissociation curve to the left. Blood transfusion also deranges fluid balance, electrolytes and coagulation (Box 2.3). For this reason, when required, preoperative blood transfusions should wherever possible be given at least 48 hours preoperatively. It is now possible for patients to store their own blood prior to big operations.

Complications of blood transfusion

Early

Fluid balance

Water

The basic principle behind fluid balance is that what goes out must come in. Water losses occurring through the skin, the lungs as water vapour, kidneys as urine and GI tract as faeces approximate to 2500 mL/day (Table 2.1).

Table 2.1 24-hour intake and output of water and electrolytes in health

| Substance | Intake | Excretion and route |

|---|---|---|

| Water | 2000–2500 mL (plus 500 mL of water of oxidation – needs consideration if renal excretion is limited) | Kidney (1500 mL) and insensible loss (respiratory and sweating, 1000 mL) |

| Sodium | 100 mmol | Kidney (but sweat also up to 120 mmol/L) |

| Potassium | Up to 100 mmol | Kidney; restricted input not followed by fall in excretion |

Electrolytes

Specific electrolyte problems

Hypernatraemia

This occurs with dehydration in the postoperative surgical patient or when too much saline is given when aldosterone secretion is high. It may be a complication of Conn’s syndrome (see Ch. 11). In the former case, rehydration is needed, and in the latter case, sodium restriction. Electrolytes need to be checked twice daily in these situations.

Acid–base balance

Metabolic acidosis

This is commonly seen in surgery where there is a failure of oxygen transport and excess acid production due to anaerobic metabolism (lactic acidosis). Fluid loss, bleeding or sepsis may cause peripheral circulatory failure (see Ch. 3). Initial compensation occurs in the lungs but when, for example, sepsis is prolonged, ventilatory failure also occurs. Mechanical ventilation often restores the balance whilst additional compensation is provided by the kidneys. If acidosis is persistent despite the above measures, intravenous administration of sodium bicarbonate may correct the situation.

Infections and antibiotics

The propensity for an infection to develop depends on the size of the inoculum, the pathogenicity of the organism and ability of the patient to resist the infection. Steroid therapy, diabetes, malnutrition, lower resistance, alcoholism, AIDS and immunosuppression from any cause (Box 2.4) all promote infection, while locally the main factors are necrotic tissue, blood clot, foreign bodies and ischaemia.

Antibiotic prophylaxis

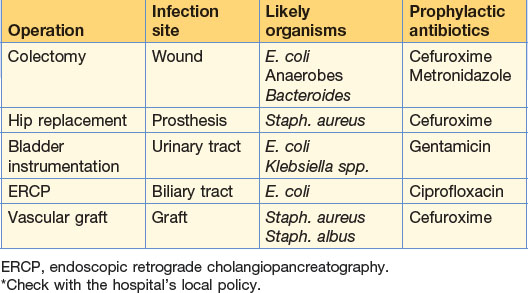

Patients at high risk should be given antibiotic prophylaxis. The choice of antibiotic depends on the type of operation, the most likely organisms to be encountered, the likelihood of the development of resistance, and financial costs involved (risk management) (Table 2.2). Cephalosporins are widely used in general and orthopaedic surgery and given at the time of induction. Two further doses over 24 hours are sufficient thereafter. Antibiotics may be administered orally, rectally, intravenously or topically. Long-term prophylaxis, for example in post-splenectomy patients, is given to prevent overwhelming infections.

Principles of antibiotic usage

The choice of agent is often directed by microbiological advice. The more expensive drugs are not necessarily the best. A suggested list of antimicrobial chemotherapy is shown in Table 2.3.

| Antibiotic | Common uses | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Penicillin | All cocci: strepto-, staphylo-, pneumo- | 85% of staphylococci resistant due to beta-lactamase production Allergies common: simple rash to fatal anaphylaxis |

| Flucloxacillin | Antl-staphylococci; included In treatment of cutaneous infections | |

| Co-amoxiclav | Broad-spectrum: soft tissue infections, pneumonia, UTI and antibiotic prophylaxis | Combination of amoxicillin (amoxycillin) and clavulanlc acid; latter prevents action of beta-lactamases |

| Amoxicillin | Active against Gram-negative and -positive organisms: urinary tract and respiratory infections | An amino group added to the basic penicillin molecule gives increased antimicrobial activity |

| Piperacillin | For severe infections in combination with gentamicin (for Gram-negative, resistant organisms) | Later-generation penicillin that has activity against Pseudomonas |

| Ticarcillin + clavulanic acid | Same uses as piperacillin | |

| Cefuroxime | Broad-spectrum: prophylaxis bowel and biliary operations; treatment of Gl conditions – cholecystitis, appendix mass, diverticulitis | Second-generation cephalosporin In common use in Gl surgery often in combination with metronidazole 10% of those allergic to penicillin similarly affected by cephalosporins |

| Cefotaxime or ceftazidime | Second-line treatment for sepsis insensitive to cefuroxime | Third-generation cephalosporin Some improvement in activity against Gram-negative organisms but slightly poorer against staphylococci |

| Imipenem | Broad-spectrum – for use in ICU | A carbapenem–thienamycin beta-lactam best combined with cilastatin – an enzyme inhibitor of its metabolism by the kidney |

| Tetracycline | Pelvic inflammatory disease; other sexually transmitted diseases | Bacteriostatic rather than bactericidal, but active against Chlamydia |

| Gentamicin | Severe sepsis (in combination with penicillin or metronidazole) | Aminoglycoside active against Gram-negative organisms and Pseudomonas; inactive against anaerobes and streptococci |

| Prophylaxis during urinary tract instrumentation | Potentially nephrotoxic; serum levels must be regularly checked | |

| Erythromycin | Soft tissue and chest infections | Active against staphylococci and H. influenzae Useful in those allergic to penicillin |

| Clarithromycin | Similar to erythromycin | Used for Helicobacter pylori infections of the upper Gl tract |

| Vancomycin | Gram-positive infections resistant to penicillins and cephalosporins (MRSA and pseudomembranous colitis) | |

| Teicoplanin | Similar uses to vancomycin | Requires administration by intramuscular or intravenous route |

| Trimethoprim | Urinary tract infections | |

| Co-trimoxazole | Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia | |

| Metronidazole | Anaerobic abdominal infections (including prophylaxis and usually in combination) Gas gangrene Amoebic infections Pseudomembranous colitis |

|

| Ciprofloxacin | Gram-negative infections – Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter | 4-Quinolone – the traveller’s antibiotic |

| Examples of typical antibiotic choices for particular clinical infections | ||

| Infection | First choice | Alternatives |

| Chest infection | Penicillin + erythromycin | Co-amoxiclav |

| Wound Infection (cellulitis) | Penicillin + flucloxacillin | Co-amoxiclav |

| Intra-abdominal infection (endogenous organisms likely) | Cefuroxlme + metronidazole | Cefotaxime Gentamicin |

| Cholecystitis-cholangitis | Cefuroxime + metronidazole | Piperacillin |

| Urinary tract infection | Trimethoprim | Gentamicin Co-amoxiclav |

| Pelvic inflammatory disease | Tetracyclines + cefuroxlme + metronidazole | |

| Severe sepsis | Gentamicin + metronidazole + penicillin | Imipenem Ticarcillin |

| MRSA | Vancomycin | Teicoplanin |

| Pseudomembranous colitis | Metronidazole | Vancomycin |

| Gas gangrene | Penicillin + metronidazole | Metronidazole |

Specific infections

Septicaemia

In septicaemia, bacteria are not just present in the blood (bacteraemia), but are using it as a culture medium. Fever, tachycardia, hypotension, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and multiple organ failure may ensue (see Chapter 3). In some instances with shock, it is not the organisms that are found but circulating endotoxins (Gram-negative). Symptoms may be severe with malaise or related to the focus of infection. Repeated blood cultures may be negative. Leucocytosis is common. ‘Best-guess’ antibiotics are given immediately, usually of broad-spectrum activity.

Systemic inflammatory response (SIRS)

SIRS is the name given to a physiological state of septic collapse (see Chapter 3). The mechanism appears to be activation of macrophages and release of tumour necrosis factor (TNF). The situation is worsened by cell injury leading to deficient uptake of oxygen, tissue hypoxia and lactic acidosis. Clinically this leads to fever, oliguria, respiratory and multi-organ failure.

Deep vein thrombosis

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolus (PE) are an important cause of morbidity and mortality in surgical patients, since they often have one or more of Virchow’s triad (Box 2.5).

The main risk factors for DVT in surgical patients are:

Other risk factors are summarised in Box 2.6.

Box 2.6 Risk factors for thromboembolic disease in surgical patients

Management (see Box 2.7)

The diagnosis is best confirmed by duplex scanning. Venography is not required for acute diagnosis.

Nutrition

Nutritional support

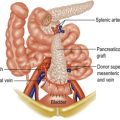

Total parenteral nutrition

Total parenteral nutrition (TPN) is given via a feeding catheter placed into the subclavian vein or superior vena cava. This can be placed percutaneously under radiological guidance. The risk of infection is high and strict aseptic conditions must be observed during placement and after care. The complications are shown in Box 2.8.

Anaesthesia

The purpose of anaesthesia is to allow the patient to undergo surgery in a safe and pain-free way. A number of different techniques and agents are used to achieve this. In the main there are two types, general (with the patient unconscious) and local/regional anaesthesia. Pre-operative preparation of the patient is crucial for the safe delivery of anaesthetic. Mostly this is straightforward but for complex procedures patients may need to be in hospital for investigations and optimisation of their underlying medical health several days before surgery. Validated scoring systems are increasingly being used for estimating the likely risks of surgery and can also be used to compare outcome data of different hospitals/surgeons (allows a correction for case-mix). POSSUM (physiological and operative severity score for the enumeration of morbidity and mortality) and APACHE (acute physiology and chronic health evaluation) score are two of the most widely used tools (see Box 2.9).

Box 2.9

Parameters used to calculate APACHE II score

(Knaus WA et al. APACHE II: A severity of disease classification system. Critical Care Medicine. 1985; 13(App)pp828-829)

Pre-assessment

Pre-assessment of patients for elective cases often occurs in an outpatient setting. A full history is taken of pre-existing co-morbidity, drugs and previous hospital admissions and reactions/problems with anaesthetics. Further investigations may be required to assess cardiac or respiratory status. Blood pressure medication may need to be reviewed and diabetes stabilised. The opportunity for fully informed consent can also be taken. A list of indications for preoperative investigations is shown in Table 2.4. An overall preoperative grading, using the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) system, is decided (Box 2.10).

| Investigation | Indication |

|---|---|

| Full blood count | History of bleeding, major surgery, cardiorespiratory disease, premenopausal women |

| Electrolytes | History of vomiting, diarrhoea, renal disease, cardiac disease, diabetes, diuretics, ACE inhibitors, anti-arrhythmics, steroids, hypoglycaemics |

| Glucose | History of diabetes, abscesses, steroids |

| Liver function tests | History of liver disease, alcoholism, bleeding, pyrexia of unknown origin |

| Clotting studies | History of liver disease, bleeding |

| Sickle cell test | Afro-Caribbeans if sickle cell status unknown |

| Electrocardiogram | History of hypertension, cardiorespiratory disease, age >55 years |

| Chest X-ray | History of cardiorespiratory disease, heavy smoker, potential metastases, recent immigrants from area where TB is endemic |

| Pulmonary function tests | Respiratory disease, thoracic surgery |

| Arterial blood gases | Respiratory disease, thoracic surgery |

| Cervical spine X-ray | Rheumatoid arthritis, trauma |

Airway examination is mandatory to assess mouth opening, jaw protrusion, neck movement, dental condition and a view of the posterior pharyngeal structures. Increasingly, pre-medication is not a necessity, particularly with day-case surgery. The commoner complications of anaesthesia are shown in Box 2.11.

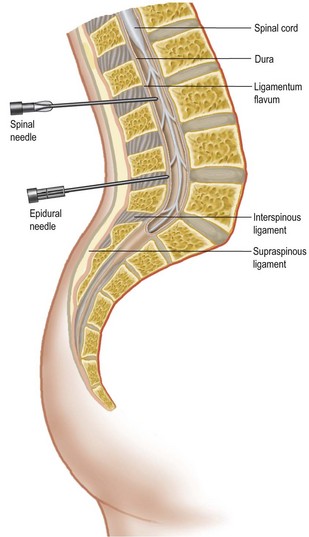

Local and regional anaesthesia

Many procedures can now be performed without a general anaesthetic. Local anaesthetic agents block the generation and propagation of nerve impulses at several sites, e.g. the spinal cord, spinal nerve roots, peripheral nerves and local nerves at the site of the procedure. Factors affecting the choice of regional anaesthesia are shown in Table 2.5. Overdose can occur and the maximum safe doses of commonly used agents are shown in Box 2.12. Local anaesthetic can be administered topically, subcutaneously, by Bier’s block (intravenous regional anaesthesia, see Box 2.13), nerve block or epidural/spinal routes. The anatomy of the latter is shown in Figure 2.1. Complications of spinal and epidural anaesthesia can be very serious, ranging from prolonged headache, prolonged hypotension and nerve root damage to epidural haematoma or abscess (which can result in paraplegia).

Table 2.5 Factors to consider in choosing regional anaesthesia

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| Avoids complications of general anaesthetic | Toxic effects of local anaesthetics |

| Contributes to postoperative analgesia | Patient unhappy to be awake |

| Less postoperative nausea and vomiting | Inadequate anaesthesia |

| Patient satisfaction (e.g. caesarean section) | Possible nerve damage |

| Reduces incidence of DVT | Can be slow onset |

Monitoring and charting the anaesthetised patient

Apart from clinical observation, standard monitoring is directed to the cardiovascular and respiratory systems (Box 2.14). Continuous ECG and automated blood pressure measurement are mandatory. Pulse oximetry provides continuous oxygenation information. Measurement of exhaled gases also occurs, indicating if ventilation is adequate. Complex cases often utilise further monitoring, e.g. intra-arterial lines, central venous pressure measurement, cardiac output devices (e.g. oesophageal Doppler) and urine output. All these methods carry a small measure of morbidity and complication rate. However, it is increasingly recognised that optimal fluid management using these devices optimises outcome and shortens in-patient hospital stay.

The agents used during the procedure may be classified into:

(a) induction agents (e.g. thiopentone or propofol)

(b) inhalational maintenance agents (halothane, sevoflurane, isoflurane, nitrous oxide)

(c) neuromuscular blocking agents (suxamethonium, vecuronium)

The criteria for discharge from the recovery unit are shown in Box 2.15. Specific signs that may be important in the early postoperative phase are shown in Table 2.6.

Table 2.6 Specific signs that may be important in the early postoperative period

| Sign | Possible meanings |

|---|---|

| Respiratory distress: tachypnoea, cyanosis | Hypoxia |

| CNS signs: | |

| CNS depression | Oversedation |

| Agitation | Carbon dioxide retention Blood loss Hypoxia Pain |

| Disorientation | Inappropriate sedation Hypoxia |

| Severe inappropriate pain | Local complication at site of operation – bleeding, leakage of secretions, ischaemia |

| Wound: | |

| Bleeding | Uncontrolled blood vessel |

| Soft tissue haematoma | Clotting disorder |

| Irregular pulse | Unrecognised cardiac disorder Hypoxia |

| Skin pallor, empty veins, hypotension, tachycardia | Hypovolaemia |

Pain and its relief

Post-operative pain is inevitable for most patients. It can have serious physiological and psychological consequences (Table 2.7). Intensity of pain is influenced by cultural and family background, personality, past experience and motivation. Pre-operative literature can inform and allay anxiety while a calming, reassuring attitude from the medical and nursing staff will contribute to pain reduction. Pain management has become a subspecialty in its own right and principles only will be discussed here.

| Effect | Outcome |

|---|---|

| Decreased respiratory excursion | Hypoventilation Pulmonary collapse/consolidation |

| Gastrointestinal atony | Ileus, nausea and vomiting |

| Bladder atony | Urinary retention |

| Catecholamine release | Vasoconstriction; increased blood viscosity, clotting activity and platelet aggregation; raised cardiac work |

Therapy

All agents are better given on a regular basis. Mild pain may be treated with NSAIDs and paracetamol. Moderate pain responds well to mixtures of codeine and paracetamol. Narcotic analgesics (e.g. morphine) are widely used for severe pain and are delivered in a variety of regimens (orally, subcutaneous infusion, intramuscularly and intravenously, more often controlled by the patient – PCA) (Table 2.8). A combination of these drugs usually produces the best results. Pre-emptive analgesia before the operation has been started is also useful (e.g. infiltrating the skin prior to incision).

Table 2.8 Standard postoperative analgesia regimens (fit, adult, male, 70 kg)

| Grade of surgery | Example | Postoperative analgesia |

|---|---|---|

| Minor | Lipoma removal | Paracetamol, 1 g, 6-hourly |

| Intermediate | Arthroscopy Hernia repair |

Co-dydramol, 2 tablets, 6-hourly + diclofenac, 50 mg orally, 8-hourly |

| Major | Laparotomy Hip replacement |

Morphine PCA, 1 mg bolus, 5 min lock-out + diclofenac, 50 mg orally, 8-hourly |

PCA, patient-controlled analgesia.