Chapter 1 Overview of Pediatrics

Scope and History of Pediatrics and Vital Statistics

Reducing Child Mortality

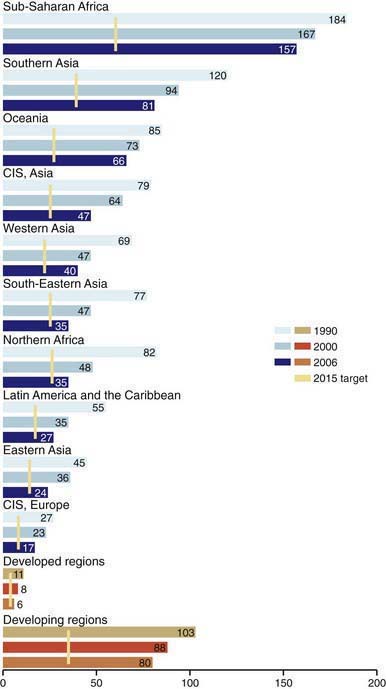

Despite global interconnectedness, child health priorities continue to reflect local politics, resources, and needs. The state of health of any community must be defined by the incidence of illness and by data from studies that show the changes that occur with time and in response to programs of prevention, case finding, therapy, and surveillance. To ensure that the needs of children and adults across the globe were not obscured by local needs, in 2000 the international community established 8 Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) to be achieved by 2015 (www.countdown2015mnch.org). Although all 8 MDGs impact child well-being, MDG 4 (“Reduce by two-thirds, between 1990 and 2015, the under-five mortality rate”) is exclusively focused on children. Globally, there has been a 23% reduction in under-5 mortality since 1990 (from 93 to 72 deaths per 1,000 live births), with a 40% reduction in developed countries (10 to 6) but only a 21% reduction in the least developed countries (180 to 142). In 62 countries progress was inadequate to meet the goals and 27 countries (including most of those in sub-Saharan Africa) made no progress or declined between 1990 and 2006. There were nearly 13 million under-5 deaths in 1990; 2006 marked the 1st year that there were fewer than 10 million deaths (9.7 million) with a further decrease to 9.0 million in 2007 and 8.8 million in 2008. However, overall progress has not been on target to reach the goal (Fig. 1-1).

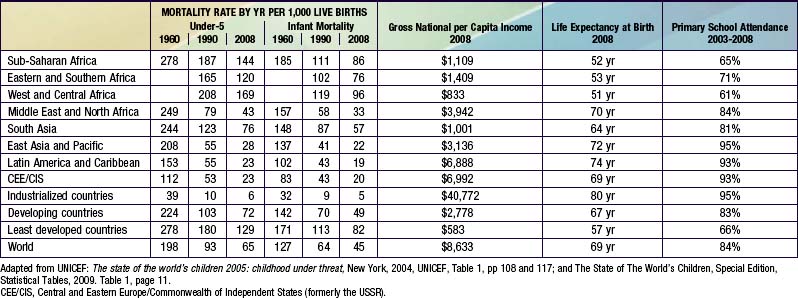

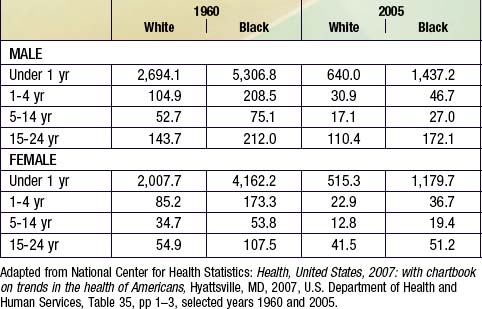

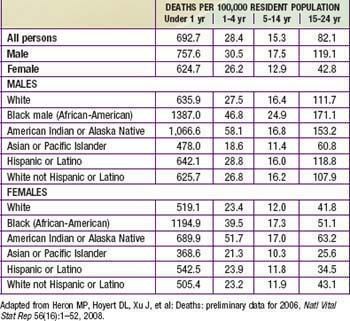

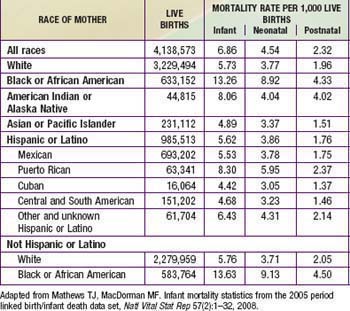

Across the globe, there are significant variations in infant mortality rates by nation, by region, by economic status, and by level of industrial development, the categorizations employed by the World Bank and the United Nations (Table 1-1). Most of the decline in infant mortality in the USA and other industrialized countries since 1970 is attributable to a decrease in the birthweight-specific infant mortality rate related to neonatal intensive care, not to the prevention of low-birthweight births (Chapter 87). The majority of deaths of infants younger than 1 yr of age occur in the 1st 28 days of life, most of these in the 1st 7 days; moreover, a large proportion of the deaths in the 1st 7 days occur on the 1st day. An increasing number of severely ill infants born at very low birthweight survive the neonatal period, however, and die later in infancy of neonatal disease, its sequelae, or its complications (Tables 1-2 through 1-4).

Table 1-2 DEATH RATES FOR ALL CAUSES, BY SEX, RACE, AND AGE: UNITED STATES, SELECTED YEARS 1960 AND 2005

Table 1-3 DEATHS RATES FOR ALL CAUSES AMONG CHILDREN AND YOUNG ADULTS ACCORDING TO SEX, RACE, HISPANIC ORIGIN, AND AGE: 2006

Table 1-4 INFANT, NEONATAL, AND POSTNATAL DEATHS AND MORTALITY RATES BY SPECIFIED RACE OR ORIGIN OF MOTHER: USA, 2005

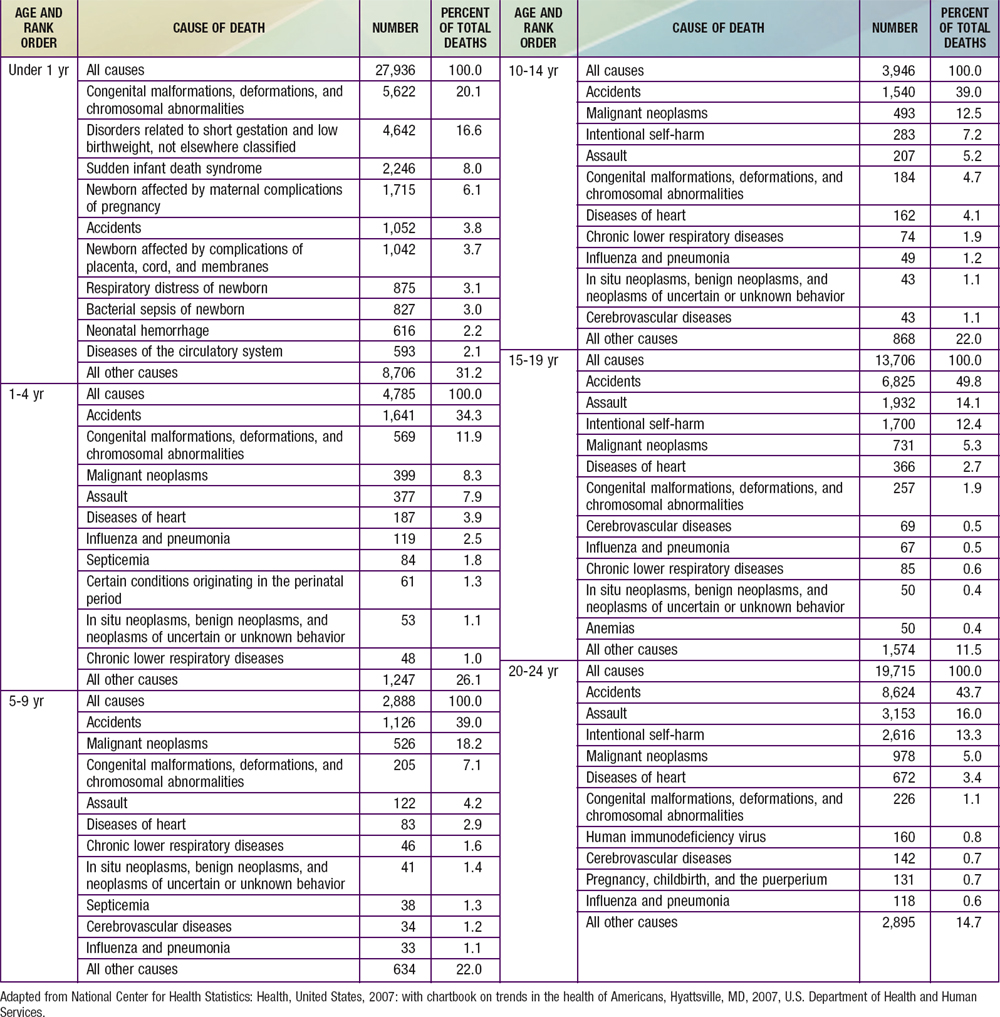

Causes of death vary by developmental status of the nation. In the USA, the 3 leading causes of death among infants were congenital anomalies, disorders related to gestation and low birthweight, and sudden infant death (Table 1-5). By contrast, in developing countries, the majority of infant deaths result from infectious diseases; even in the neonatal period, 24% of deaths are caused by severe infections and 7% by tetanus. In developing countries, 29% of neonatal deaths are due to birth asphyxia and 24% due to complications of prematurity.

Health Among Postinfancy Children

Increasing attention has also been given to behavioral and social aspects of child health, ranging from re-examination of child-rearing practices to creation of major programs aimed at prevention and management of abuse and neglect of infants and children. Developmental psychologists, child psychiatrists, neuroscientists, sociologists, anthropologists, ethnologists, and others have brought us new insights into human potential, including new views of the importance of the environmental circumstances during pregnancy, surrounding birth, and in the early years of child rearing. The later 20th century witnessed the beginning of nearly universal acceptance by pediatric professional societies of attention to normal development, child rearing, and psychosocial disorders across the continents. In the last decade, irrespective of level of industrialization, nations have developed programs addressing not only causes of mortality and physical morbidity (such as infectious diseases and protein-calorie malnutrition), but also factors leading to decreased cognition and thwarted psychosocial development, including punitive child-rearing practices, child labor, undernutrition, war, and poor schooling. Obesity is recognized as a major health risk not only in industrialized nations, but increasingly in transitional countries. Progress at the turn of the 21st century in unraveling the human genome offers for the 1st time the realization that significant genetic screening, individualized pharmacotherapy, and genetic manipulation will be a part of routine pediatric treatment and prevention practices in the future. The prevention implications of the genome project give rise to the possibility of reducing costs for the care of illness but also increase concerns about privacy issues (Chapter 3).

Enormous disparities exist in childhood mortality rates across the globe (see Table 1-1). Among the ∼8.7 million childhood deaths occurring worldwide, ≈50% occur in sub-Saharan Africa, home to <10% of the world’s population. Fifty percent of the world’s childhood deaths are occurring in 6 nations; 90% of childhood deaths are occurring in only 42 of the world’s 192 nations. In 2008, the USA had an under-5 mortality rate of 8/1,000 live births. Forty-two nations had under-5 mortality rates lower than that of the USA, with Singapore, Finland, Luxembourg, Iceland, and Sweden having the lowest rates at 3/1,000. The comparable child mortality rate in sub-Saharan Africa was 144/1,000 live births. As of 2008, Afghanistan has the highest under-5 mortality rate of 257/1,000 live births, followed by Angola at 220/1,000 live births and Chad at 209/1,000 live births. In 1990 Afghanistan and Angola had an under-5 mortality rate of 260/1,000 live births, showing minimal improvement over 2 decades. Causes of under-5 mortality differ markedly between developed and developing nations. In developing countries, 66% of all deaths resulted from infectious and parasitic diseases. Among the 42 countries having 90% of childhood deaths, diarrheal disease accounted for 22% of deaths, pneumonia 21%, malaria 9%, AIDS 3%, and measles 1%. Neonatal causes contributed to 33%. The contribution for AIDS varies greatly by country, being responsible for a substantial proportion of deaths in some countries and negligible amounts in others. Likewise, there is substantial co-occurrence of infections; a child may die with HIV, malaria, measles, and pneumonia. Infectious diseases are still responsible for much of the mortality in developing countries. In the USA, pneumonia (and influenza) accounted for only 2% of under-5 deaths, with only negligible contributions from diarrhea and malaria. Unintentional injury is the most common cause of death among U.S. children ages 1-5 yr, accounting for about 33% of deaths, followed by congenital anomalies (11%), malignant neoplasms (8%), and homicides (7%). Other causes accounted for <5% of total mortality within this age group (see Table 1-5). Although unintentional injuries in developing countries are proportionately less important causes of mortality than in developed countries, their absolute rates and their contributions to morbidity are substantially greater.

Morbidities Among Children

In the USA, ≈70% of all pediatric hospital bed days are for chronic illnesses; 80% of pediatric health expenditures are for 20% of children. In 2006, about 13.9% of U.S. children were reported to have special health care needs; 21.8 percent of households with children had ≥1 child with a special health care need (Chapter 39). Significantly more poor children and minority children have special health care needs. Although there are multiple chronic conditions and the prevalence of these disorders vary by population, 2 of these morbidities—obesity and asthma—have a substantial and increasing presence worldwide and are associated with substantial health consequences and costs. In the USA, ∼25% of children and adolescents are overweight, representing a 2.3- to 3.3-fold increase over the past 25 yr. Similar rates have been reported from Australia and multiple countries in Europe, Egypt, Chile, Peru, and Mexico (Chapter 44).

Also increasing in prevalence among industrialized nations and in middle- and low-income nations with substantial urbanization are rates of asthma. In the mid-1990s, the USA reported an annual prevalence rate of wheezing of 57.8/1,000 among children ages 0-4 yr and 74.4/1,000 among youth ages 5-15 yr, approximately 2-fold higher than comparable prevalence rates in 1980. In 2007, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimated that 9% of U.S. children have asthma, including 19.2% of Puerto Rican and 12.7% of non-Hispanic black children. The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood has conducted a systematic review of asthma prevalence, with compelling evidence for a substantial global burden of childhood asthma, although rates vary substantially between and within countries. The highest annual prevalence rates are in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, and Ireland, with the lowest rates in Eastern European countries, Indonesia, China, Taiwan, India, and Ethiopia (Chapter 138).

Chronic cognitive morbidities represent another substantial problem. Although different diagnostic criteria have been applied, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) has been identified in 5-12% of children in countries across the globe. Rates exceeding 10% have been reported in the USA, New Zealand, Australia, Spain, Italy, Colombia, and Great Britain. Variations in cultural tolerance and/or differences in screening approaches or tools may account for some of the differences in prevalence of the disorder by country, but genetic and gene-environmental interactions may also play a role. Despite variations in rate, the condition is universal. Beyond the personal and familial stress caused by the disorder, costs to the educational system are considerable. It is estimated that in 2010 the U.S. drug treatment costs for ADHD will exceed $4 billion. In developing countries without resources for special education, these children are unlikely to fulfill their academic potential (Chapter 30).

Mental retardation affects ≈1-3% of children in the USA, with ∼80% of these children having mild retardation. Rates are severalfold higher among very low birthweight infants, although data from European cerebral palsy (CP) registries has revealed a significant decrease in the prevalence of CP in very low birthweight infants, from 60.6 per 1,000 live births in 1980 to 39.5 per 1,000 live births in 1996. In the USA, there is substantial variation in rates of mild retardation by socioeconomic status (9-fold higher in the lowest compared to the highest socioeconomic stratum) but relatively equivalent rates of severe retardation. A similar income-related distribution is found in other countries, including some of the most impoverished countries such as Bangladesh. Lower overall rates have been reported in some countries, including countries ranging from Saudi Arabia to Sweden to China; the difference is primarily in the prevalence of mild retardation (Chapter 33).

Special Risk Populations

Children in Poverty

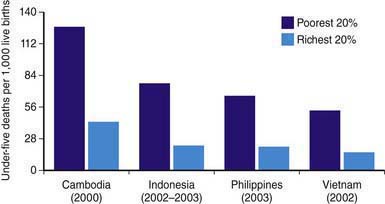

Similar poverty-linked disparities may exist in countries with very high infant mortality rates (sub-Saharan Africa). In the low-income developing countries, the rate of infant mortality among the poorest quintile of the population is more than twice that of the wealthiest quintile (Fig. 1-2).

Children of Immigrants and Racial Minority Groups Including U.S. Native Americans

Families of different origins obviously bring different health problems and different cultural backgrounds, which influence health practices and use of medical care. To provide appropriate services, clinicians need to understand these influences (Chapter 4). For example, the high prevalence of hepatitis among women from Southeast Asia makes use of hepatitis B vaccine essential for their newborns. Children from Southeast Asia and South America have growth patterns that are generally below the norms established for children of Western European origin, as well as high rates of hepatitis, parasitic diseases, and nutritional deficiencies and high degrees of psychosocial stress. Foreign-born children may surpass American-born children in some health outcomes, but their health deteriorates as they become acculturated (Chapter 4).

Refugee children who escape from war or political violence and whose families have been subjected to extreme stress represent a subset of immigrant children who have faced severe trauma. These children have a particularly high incidence of mental and behavioral problems (Chapter 23).

“Linguistically isolated households,” in which no one older than 14 yr of age speaks English, often present significant obstacles to providing quality health care to children because of difficulties in understanding and communicating basic concerns and instructions, avoiding compromising privacy and confidentiality interests, and obtaining informed consent (Chapter 4).

The USA is home to multiple minority populations, including the 2 largest groups, Latinos and African-Americans. The nonwhite minority groups will constitute >50% of the U.S. population by 2050 (Chapter 4). Nonwhite children in the USA disproportionately experience adverse child health outcomes (see Tables 1-2 through 1-4). Infants that are born to African-American mothers experience low birthweight and infant mortality rates twice those with white mothers (Chapter 87). Rates of these 2 adverse health outcomes are also substantially higher among some groups of Hispanic infants and children, although there is great variation by country of origin. The rates are particularly high among those of Puerto Rican descent (≈1.5 times the rates for white infants). In 2006, the overall infant mortality rate was 6.7/1,000 live births, whereas that for non-Hispanic African-America infants was 13.6; for Native Americans, 8.1; and for Puerto Ricans, 8.3. Mexicans, Asians, Pacific Islanders, Central and South Americans, and Cubans were below the national average. Latino, Native American, and African-American children are substantially more likely to live in poverty than are white children.

Runaway and Thrown-Away Children

In the USA, it is a minority of runaway youths who become homeless street people. These youths have a high frequency of problem behaviors, with 75% engaging in some type of criminal activity and 50% engaging in prostitution. A majority of permanent runaways have serious mental problems; more than 33% are the product of families who engage in repeated physical and sexual abuse (Chapter 37). These children also have a high frequency of medical problems, including hepatitis, sexually transmitted infections, and drug abuse. Although runaways often distrust most social agencies, they will come to and use medical services. Medical care may become the point of re-entry into mainstream society and the path to needed services. U.S. parents who seek a physician’s advice about a runaway child should be asked about the child’s history of running away, the presence of family dysfunction, and personal aspects of the child’s development. If the youth contacts the physician, the latter should examine the youth and assess his or her health status, as well as willingness to return home. If it is not feasible for the youth to return home, foster care, a group home, or an independent living arrangement should be sought by referral to a social worker or a social agency. Although legal considerations involved in the treatment of homeless minor adolescents may be significant, most states, through their “Good Samaritan” laws and definitions of emancipated minors, authorize treatment of homeless youths. Legal barriers should not be used as an excuse to refuse medical care to runaway or thrown-away youths.

The Challenge to Pediatricians

The unfinished business in the quest for physical, mental, and social health in the community is illustrated by the disparities with which deaths due to disease, injuries, and violence are distributed among white, black, and Hispanic children in the USA and between and within nations. Homicide is a major cause of adolescent deaths and has increased in rate among the very young, in whom the increase may, in part, represent the more accurate identification of child abuse (Chapter 37). Among adolescents, homicide may reflect unresolved social tensions, substance abuse (cocaine, crack), and an unhealthy preoccupation with violence in our society (Part III and Chapters 36, 107, and 108).

Planning and Implementing a System of Care

New insights into the needs of children have reshaped the child health care system in other ways. Growing understanding of the need of infants for certain qualities of stimulation and care has led to revision of the care of newborn infants (Chapters 7 and 88) and of procedures leading to an adoption or to placement with foster families (Chapters 34 and 35). For handicapped children, the massive centralized institutions of past years are being replaced by community-centered arrangements offering a better opportunity for these children to achieve their maximum potential.

Health Services for At-Risk Populations

To address the special needs of Native Americans in the USA, the Indian Health Service, established in 1954, has been the responsibility of the Public Health Service, but the 1975 Indian Self-Determination Act gave tribes the option of managing Native American health services in their communities. The Indian Health Service is managed through local administrative units, and some tribes contract outside the Indian Health Service for health care. Much of the emphasis is on adult services: treatment for alcoholism, nutrition and dietetic counseling, and public health nursing services. There are also >40 urban programs for Native Americans, with an emphasis on increasing access of this population to existing health services, providing special social services, and developing self-help groups. In an effort to accommodate traditional Western medical, psychologic, and social services to the Native American cultures, such programs include the “Talking Circle,” the “Sweat Lodge,” and other interventions based on Native American culture (Chapter 4). The efficacy of any of these programs, especially those to prevent and treat the sociopsychologic problems particular to Native Americans, has not been determined.

Costs of Health Care

The growth of high technology, the increasing number of people older than 65 yr, the redesign of health institutions (particularly with respect to the needs for and the uses of personnel), the public’s demand for medical services, the increase in administrative bureaucracies, and the manner in which the costs of health care are paid have driven the costs of health care in the USA up to a point at which they represent a significant proportion of the gross national product. Although children (0-18 yr) represent about 25% of the population, they account for only about 12% of the health care expenditures, or about 60% of adult per capita expenditures. Efforts to contain costs have led to revisions of the way in which physicians and hospitals are paid for services. Limits have been set on the fees for some services, capitated prepayment and various managed care systems flourish, a program of reimbursement (diagnosis-related groups [DRGs]) based on the diagnosis rather than on the particular services rendered to an individual patient has been implemented, and a relative value scale for varying rates of payment among different physician services has been instituted. These and other changes in the system of financing health services raise important ethical, quality of care, and professional issues for pediatricians to address (Chapter 3).

Evaluation of Health Care

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) issued a report, “Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century” in 2001. This report, challenging American physicians to renew efforts to focus not just on access and cost, but also on quality of care, has been furthered in several pediatric initiatives, including but not limited to: specific initiatives for monitoring child health outlined in the IOM report “Children’s Health, the Nation’s Wealth”; challenge/demonstration grants funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; and the National Initiative for Children’s Healthcare Quality. Importantly, each of these initiatives is calling for the establishment of measurable standards for assessment of quality of care and for the establishment of routine plans for periodic reassessment thereof. Efforts have been initiated at some medical centers to establish evidence-based clinical pathways for disorders (such as asthma) where there exists sound evidence to advise these guidelines. Pediatricians have developed tools to evaluate the content and delivery of pediatric preventive “anticipatory guidance,” the cornerstone of modern pediatrics (Chapter 5).

Organization of the Profession and the Growth of Specialization

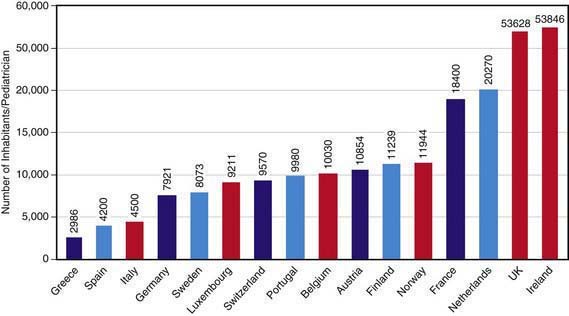

In the USA, most subspecialists practice in academic settings or children’s hospitals. Likewise, specialists are growing in number in other industrialized countries and in developing nations that are becoming industrialized. Reflecting the diverse cultures, organization of medical care, economic circumstances and the history of medicine within each of the ∼200 countries across the globe, is the great diversity in role of pediatricians within the health care delivery system to children in each country; Figure 1-3 illustrates the result variations in pediatricians per population among European nations.

American Hospital Association: Coverage counts: supporting health and opportunity for children. Trendwatch, February, 2007.

Annie E. Casey Foundation: 2008 KIDS COUNT data book: state profile of child well-being. Baltimore: Annie E. Casey Foundation; 2008.

Belamarich PF, Gandica R, Stein RE, et al. Drowning in a sea of advice: pediatricians and American Academy of Pediatrics policy statements. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e964-e978.

Black E, Morris S, Bryce J. Where and why are 10 million children dying every year? Lancet. 2003;361:2226-2234.

Bryce J, El Arifeen S, Bhutta ZA, et al. Getting it right for children: a review of UNICEF joint health and nutrition strategy for 2006–2015. Lancet. 2006;368:817-818.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital signs, nonfatal, motor vehicle-occupant injures (2009) and seat belt use (2008) among adults—United States. MMWR. 2011;59:1681-1686.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Drivers aged 16 or 17 years involved in fatal crashes—United States, 2004-2008. MMWR. 2010;59:1329-1334.

Chartrand MM, Frank DA, White L, et al. Effect of parents’ wartime deployment on the behavior of young children in military families. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162:1009-1014.

Dwivedi KN, Banhattie RG. Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and ethnicity. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:i10-i12.

Haskins R, Greenberg M, Fremstad S. Federal policy for immigrant children: room for common ground? Future Child. 2004;14:1-6.

Horton R. Indigenous peoples: time to act now for equity and health. Lancet. 2006;367:1705-1707.

Lee TH. The future of primary care. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2085-2092.

Machel G. Promotion and protection of the rights of children: impact of armed conflict on children. New York: United Nations; 1996.

Marmot M. Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet. 2006;365:1099-1104.

Mathews TJ, MacDorman MF. Infant mortality statistics from the 2005 period linked birth/infant death data set. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2008;57(2):1-32.

Mathews TJ, Miniño AM, Osterman MJK, et al. Annual summary of vital statistics: 2008. Pediatrics. 2011;127:146-157.

Navarro V, Muntaner C, Borrell C, et al. Politics and health outcomes. Lancet. 2006;368:1033-1037.

Oberg CN, Rinaldi M. Pediatric health disparities. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2006;36:245-276.

Okie S. Global health: the Gates-Buffett effect. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1084-1088.

Pais MS, Bissell S. Overview and implementation of the UN convention on the rights of the child. Lancet. 2006;367:689-701.

Pi HC, Greco G, Powell-Jackson T, et al. Countdown to 2015: assessment of official development assistance to maternal, newborn, and child health, 2003-08. Lancet. 2010;376:1485-1496.

Srivastava R, Norlin C, James BC, et al. Community and hospital-based physicians’ attitudes regarding pediatric hospitalist systems. Pediatrics. 2005;115:34-38.

United Nations. The millennium development goals report 2008. New York: United Nations; 2008.

United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). The state of the world’s children: special edition. New York: United Nations; 2009.

United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). The state of the world’s children 2008. New York: UNICEF; 2008.

U.S. Census Bureau. Income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the US: 2007. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2008.

Wise PH. The future pediatrician: the challenge of chronic illness. J Pediatr. 2007;151(Suppl 5):S6-S10.

2010 World Health Organization and UNICEF. Countdown to 2015 decade report (2000–2010). Taking stock of maternal, newborn, and child survival. Geneva: WHO Press; 2010.

You D, Jones G, Hill K, et al. Levels and trends in child mortality, 1990-2009. Lancet. 2010;376:931-934.