Chapter 26 Ovarian Cancer

Epidemiology

Ovarian carcinoma is a dismal disease, usually presents at an advanced stage, and remains the deadliest form of gynecologic malignancy. Ovarian cancer is the most common cause of death from cancer in women with gynecologic malignancy and results in 5% of overall deaths due to cancer.1 In the United States, an estimated 21,990 new cases and 15,460 deaths were projected for 2011.1

Ovarian cancer occurs sporadically in 90% of patients, and in only 10% of patients, it occurs with predisposing inherited syndromes.2 Various etiologies are connected to ovarian cancer, and the most important risk factor is a family history of the disease.3 These patients are usually younger, and most of them are premenopausal at presentation. Three different hereditary syndromes have been liked to these tumors. The most common of these is the breast-ovarian cancer syndrome, which has been linked to mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 tumor suppressor genes.3,4 The lifetime risk of developing ovarian cancer in these women ranges from 15% to 30%, although some have reported it to be as high as 60%.4 Two other hereditary syndromes are the site-specific ovarian cancer syndrome and the nonpolyposis colorectal cancer or Lynch syndrome II. The Lynch syndrome is characterized by early-onset upper gastrointestinal tract cancer, colorectal carcinoma, upper urothelial tract cancer, endometrial cancer, and ovarian cancer.5

BRCA1 mutations have also been found in 8% to 10% of sporadic ovarian cancers,6 and these sporadic cancers occur in a predominantly older, postmenopausal population. One of the theories suggested is “incessant ovulation,” although its controversial.7–9 The hypothesis suggests that repeated minor trauma related to ovulation and repair predisposes the ovary to neoplasia. Several observations support this theory such as nulliparity, early menarche, and late menopause. Conversely, multiparity, late menarche, early menopause, and use of oral contraceptives (i.e., fewer ovulation cycles) reduce the risk.10 This theory can also describe the geographic differences in prevalence of ovarian cancer rates because ovarian cancer is seen more in industrialized countries, where women tend to have fewer children, and less in countries where birth rates are higher.11

Anatomy and Pathology

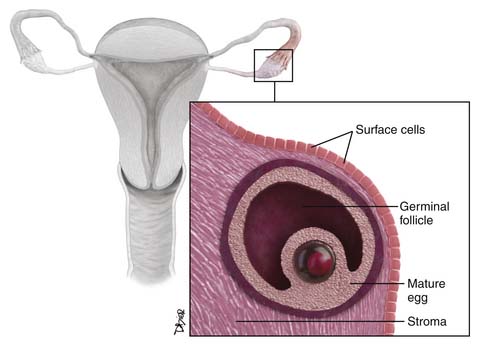

The ovaries are oval structures usually present in the pelvis and measure between 3 and 5 cm. The surface epithelial cells (Figure 26-1), which are derived from the coelomic epithelium, form a lining around them. The internal structure of the ovary is made of dense, fibrous tissue also called the stroma and is derived from the mesenchymal cells. The oocytes, which are also known as the germ cells, are located along the periphery of the stroma. The germinal cells form the follicles; these are surrounded by specialized cells of the mesonephric origin called the granulosa cells. The cells of the stroma immediately surrounding the follicles transforms to cells known as theca cells. The hilus cells of the ovary are similar to the testicular cells, known as Leydig cells, and produce hormones. There is a network of cellular cords and tubes, which is similar to a testicular structure known as the rete testis, and is called the rete ovary.12

Classification

The classification of ovarian tumors is developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO).13

Approximately 90% of primary ovarian cancers arise from the surface epithelium, which is similar to the mesothelium, which lines the peritoneal cavities and is also called the coelomic epithelium.12

The ovarian germ cell tumors arise from the germ cells of the ovaries.12

The sex cord tumors include tumors of mesonephric and mesenchymal origin. Fibromas and thecomas are fibrous in appearance, and some are derived from the granulosa cells or testicular sex cord counterparts, such as the Leydig and Sertoli cells.12

Surface Epithelial Tumors

Epithelial tumors account for approximately 60% of all ovarian tumors and approximately 90% of malignant ovarian tumors. The prevalence of these tumors usually increases with age and has a peak incidence between 60 and 70 years old. They are further divided into benign, borderline (low malignant potential), and malignant depending on their cellular proliferation.12,14 Based on their degree of differentiation, the malignant tumors can be categorized as well differentiated (10%), moderately differentiated (25%), and poorly differentiated (65%); the poorly differentiated tumors are associated with worse prognosis. The most common subtype of epithelial neoplasms is the serous tumors followed by mucinous neoplasms and endometrioid carcinomas. The clear cell carcinoma and the Brenner tumor are rare.15

Although sometimes difficult, the goal of radiologic assessment is to differentiate malignant tumors from benign tumors, rather than determining their histologic subtype. Sometimes, it may be possible to suggest the histologic subtype based on imaging features.16

Epidemiology and Pathology

Epithelial Tumors

Serous Tumors

Serous tumors are epithelial tumors and originate from the transformed cells of the coelomic epithelium, which resemble the internal lining of the fallopian tube. The benign serous tumors are usually unilocular but can be multilocular thin-walled cysts filled with watery straw-colored fluid.12 They usually do not have papillary projections, but if present, they are small compared with the borderline tumors. In up to 57% of patients, benign serous tumors are bilateral, occurring simultaneously in both ovaries.15 Most serous tumors are benign (60%), Fifteen percent are borderline and approximately 25% are malignant.

The malignant forms of these tumors tend to have a larger soft tissue component than the benign variety and can have focal areas of hemorrhage and necrosis.17 Microcalcifications (psammoma bodies) are seen in 30% of the malignant serous tumors at histologic analysis.18

Serous carcinomas are usually bilateral in more than 50% of cases.15 The primary neoplasm in these cases is small compared with the associated large-volume ascites. These tumors have large polypoid excrescences and may contain punctuate calcifications. Peritoneal carcinomatosis and omental caking are invariably seen in this setting.

Mucinous Tumors

Mucinous tumors are epithelial ovarian tumors that arise from the transformed cells of the coelomic epithelium that look like the cells of the endocervical epithelium (endocervical or müllerian type) or like the epithelium of the intestine (intestinal type).12

Benign mucinous tumors are usually multilocular with thin-walled locules filled with mucin, but they can be complicated with hemorrhage. One fourth of all benign ovarian neoplasms are mucinous tumors, and 75% to 85% of all mucinous ovarian tumors are benign.12 Benign mucinous tumors most frequently occur between the third and the fifth decades of life19 and are bilateral 21% of the time.15 Borderline mucinous tumors are similar to benign mucinous tumors but may have solid soft tissue nodules or papillar projections. The malignant counterparts have more solid components than the borderline tumors. Following rupture of these tumors, the endocervical mucinous tumors may be associated with mucinous tumorlets or implants whereas the intestinal type may be associated with pseudomyxoma peritonei. Most cases of pseudomyxoma peritonei arise from the appendiceal mucinous tumors with secondary involvement of the ovaries.12 Similarly 80% of mucinous tumors are benign, 10% to 15% are borderline and 5% to 10% are malignant.16

Endometrioid Tumor

These tumors are often malignant and may be cystic or predominantly solid.20 These are the second most common malignant ovarian surface epithelial tumors and occur in the sixth decade of life.19,20 Approximately 26% of these tumors are bilateral.15 Most malignant endometrioid tumors are confined to the ovaries and adjacent pelvic structures; 20% to 25% are associated with endometrial carcinoma.12 Malignant ovarian endometrioid carcinomas are considered to have a better prognosis than either mucinous or serous carcinomas.

Clear Cell Tumors

Clear cell tumors are epithelial ovarian tumors that are formed by clear, peglike or hobnail-like cells.12,21 These tumors are usually cystic and unilocular, containing solid rounded intramural nodules. Most clear cell tumors are malignant and represent 4% to 5% of all malignant ovarian epithelial tumors.12 They predominate in the fifth decade of life.19 Women with malignant clear cell tumors usually do not conceive, and approximately 50% to 70% of these tumors are associated with endometriosis.12

Transitional Cell Epithelial Tumors or “Brenner’s Tumors”

Transitional cell tumors arise from transformed cells of the coelomic epithelium that resemble transitional epithelium or the urothelium. These tumors are thought to be derived from surface ovarian epithelium that undergoes urothelium-like transformation (e.g., urothelial metaplasia, Walthard nests).22 They may be associated with similar tumors in the urinary bladder and are benign and consist of 1% to 3% of all ovarian tumors.23 They are solid and nodular, and most are unilateral. They can be found in conjunction with mucinous cystadenomas or other epithelial tumors.20 Most transitional ovarian tumors are very small, asymptomatic, incidentally discovered, and clinically irrelevant. They are usually seen in the fourth and fifth decades of life.23 Malignant transitional cell tumors can contain solid and cystic areas and intramural nodules.24 These tumors can associate with mucinous tumors in approximately 30% of cases that occur in the same ovary.16,25

Epithelial Tumors of Low Malignant Potential (Borderline Tumors)

Approximately 15% to 20% of all ovarian epithelial neoplasms are of borderline type and approximately 5% to 7% are mucinous type, the second most common type behind the serous borderline tumors.26 These are intermediate in their histologic and prognostic features between the benign cystadenomas and the clearly malignant carcinomas and lack stromal invasion. Compared with malignant serous tumors, borderline tumors are found in younger patients by 10 to 15 years. Malignant tumors are seen at approximately 45 years of age16,27 and account for one fourth of all ovarian neoplasms and two thirds of all ovarian serous tumors.12 The borderline tumors occur most commonly in childbearing age, show an indolent course, and usually have a better prognosis.28,29 They are usually seen in patients who are of childbearing age and approximately one third of the patients are nulliparous.28 The mucinous tumors are more common than the serous tumors.28 Serous tumors are frequently bilateral compared with the mucinous tumors. They are usually diagnosed during surgery and more than 90% of the tumors are stage I at presentation.28 Generally, these tumors present in a manner similar to other epithelial tumors and present with elevated CA125.28

Mixed Epithelial Tumors

Mixed epithelial tumors are composed of various subtypes of surface epithelial tumors. Every combination of epithelial tumors has been encountered. The tumor is named after the component that predominates but the tissue has to constitute greater than 10% of the entire tumor.20

Key Points Epithelial tumors

• Serous cystadenomas are cystic tumors that are often bilateral and unilocular and contain punctuate calcifications.

• Mucinous cystadenomas are cystic multilocular tumors with different consistencies of fluid and no solid component.

• Endometrioid tumors have solid and cystic components and are associated with hyperplasia or endometrial carcinoma.

• Clear cell cancers are usually benign and may be associated with endometriosis.

Germ Cell Tumors

Germ cell tumors arise from cells that are believed to be derived from primordial germ cells.12 Germ cell tumors usually occur in girls and adolescent females; the peak incidence is at 15 to 19 years30 and consists of 20% to 25% of all ovarian neoplasms20; only one third of these tumors are malignant.31,32 Conversely, most germ cell tumors occurring in adults are benign. Most tumors are large at presentation, and 85% of the patients present with abdominal pain mimicking appendicitis due to rupture, torsion, or hemorrhage; other symptoms include vaginal bleeding.33

Of all the germ cell tumors, the mature teratoma is benign and the rest are malignant. The malignant germ cell tumors are divided into dysgerminoma (the most common type) and nondysgerminomatous tumors. The most common types of nondysgerminomatous tumors are immature teratoma, yolk sac tumors, and mixed germ cell tumors. Less common variants of nondysgerminomatous tumors are embryonal carcinoma, polyembryoma, and nongestational choriocarcinoma.34

Benign Tumors

Mature teratomas are the most common germ cell tumors and are seen in the reproductive years.12 They are made of two or more mature embryonic germ cell layers. They are usually unilocular; in more than 80% of cases, they are filled with sebaceous material and lined by squamous epithelium.35 They have variable appearance depending on their contents such as hair follicles, skin glands, muscle, teeth, and other tissues. In rare cases, mature cystic teratomas may undergo malignant transformation, most often in postmenopausal patients, that most commonly results in squamous cell carcinoma.12

Malignant Tumors

Dysgerminoma

Dysgerminomas are rare and occur predominantly in young women. This tumor has a striking similarity to seminoma of the testis.36 Unilateral tumors are more common and 10% to 20% of dysgerminomas can be bilateral. They can be associated with congenital malformations of the genital tract and Turner’s syndrome. These tumors are usually solid and may contain cystic areas with hemorrhage and necrosis. Most occur in the second and third decades of life. Dysgerminomas account for 2% or less of all ovarian tumors and only 3% to 5% of all malignant ovarian tumors; nevertheless, they represent the most common type of malignant ovarian germ cell neoplasm occurring during pregnancy.12,20

Nondysgerminomas

Immature Teratomas

Immature teratomas represent less than 1% of all teratomas and contain primitive, immature, or embryonal structures in addition to well-developed or mature tissues.36,37 These tumors usually are unilateral, large, and predominantly solid; are rare; and occur in the first two decades of life.12 They have a solid soft tissue component, are invariably malignant, and grow rapidly. They rupture and disseminate via the lymphatic system and spread through the peritoneal cavity.

Endodermal Sinus Tumor (Yolk Sac Tumors)

Endodermal sinus tumor is a rare tumor, also known as yolk sac tumor, and displays cellular structures that resemble those of the primitive yolk sac. The tumor manifests as a large, complex pelvic mass that extends into the abdomen, contains both solid and cystic components, and tends to secrete alpha-fetoprotein.12

These tumors are malignant and usually occur in the second and third decades of life.36 Most of the tumors are usually unilateral and rare in postmenopausal women.12 No imaging features can distinguish them from other ovarian neoplasms.

Choriocarcinoma

Choriocarcinomas are germ cell tumors that arise from trophoblastic cellular elements.12 They typically are solid and have a hemorrhagic appearance. The majority of the primary ovarian choriocarcinomas are not related to pregnancy (nongestational). These occur in children and young adults. They secrete beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG), which may lead to precocious puberty and abnormal uterine bleeding. Choriocarcinomas are highly malignant, have locally invasive spread mainly via lymphatics, and seed the peritoneal cavity.12

Key Points Germ cell tumors

• Germ cell tumors account for 15% to 20% of all tumors.

• Mature teratomas have calcifications in mural nodules and are benign; immature teratomas have scattered calcifications and are malignant.

• Yolk sac tumors are the second most common germ cell tumor and secrete alpha-fetoprotein.

• Choriocarcinomas are rare aggressive tumors that are widely metastatic at the time of presentation and secrete β-hCG.

Sex Cord–Stromal Tumors

Sex cord–stromal tumors are thought to originate from sex cords or the mesenchymal cells of the embryonic gonads. They account for approximately 8% of all ovarian tumors and affect all age groups. These tumors can be divided into two groups: one that develops from the gonadal stroma such as the fibromas, thecomas, sclerosing stromal tumors, and one that develops from the sex cord such as the granulosa cell tumors and Sertoli-Leydig tumors.38

Granulosa Cell Tumor

The adult granulosa cell tumors represent 95% of the sex cord tumors of the ovary, and they produce estrogen. These tumors occur commonly in peri- and postmenopausal women. The estrogen produced by the tumor can cause endometrial hyperplasia, polyps, or even carcinoma and is associated with these neoplasms in 5% to 25% of cases.12,38 The juvenile tumors can lead to precocious puberty. They account for 5% of all granulosa cell tumors.

Fibromas

Fibromas are benign tumors that arise from the spindle stromal cells that form collagen.12 They are usually seen in postmenopausal women and do not produce estrogen. They may be associated with nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome, also known as Gorlin’s syndrome.39

Sertoli-Leydig Cell Tumors

Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors are formed by cells that resemble epithelial and stromal testicular cells12 and occur in nulliparous women younger than 25 years.40 These tumors are rare, produce androgen, and in 30% of cases, can cause a virilization syndrome.38

Key Points Sex cord tumors

• Account for 5% to 10% of all tumors.

• Fibromas and fibrothecomas can mimic fibroids and can be associated with Meigs’ syndrome or Gorlin’s syndrome.

• Granulosa cell tumors are the most common tumors, are seen in postmenopausal women, and produce estrogen. They may cause postmenopausal bleeding and, if present in young females, cause precocious puberty.

• Sertoli-Leydig tumors are seen in females of reproductive age, produce testosterone, and can cause virilization

Metastatic Ovarian Tumors

Metastatic ovarian tumors account for approximately 15% of ovarian malignancies. The most common metastatic ovarian tumors seen are of gastrointestinal origin (39%), which is followed by breast (28%).41 Usually, these tumors are bilateral, large and can mimic primary ovarian neoplasms in 25% of cases.41 Depending on the geographic locations, the most common origin of these tumors can be colon or the stomach.41 These cancers are usually 5 to 10 cm in size and may have solid and cystic components.41

Patterns of Tumor Spread

In order to recognize the radiologic findings in each of the stages, it is important to thoroughly understand the mechanism of tumor spread. Ovarian carcinoma may spread directly to the surrounding pelvic tissues, such as the fallopian tubes, uterus, and contralateral adnexa, which are commonly involved, but direct extension of tumor to the rectum, bladder, and pelvic sidewall can also be seen.42 Tumor dissemination beyond the pelvis can occur via three mechanisms: intraperitoneal seeding, lymphatic invasion, and hematogenous dissemination.

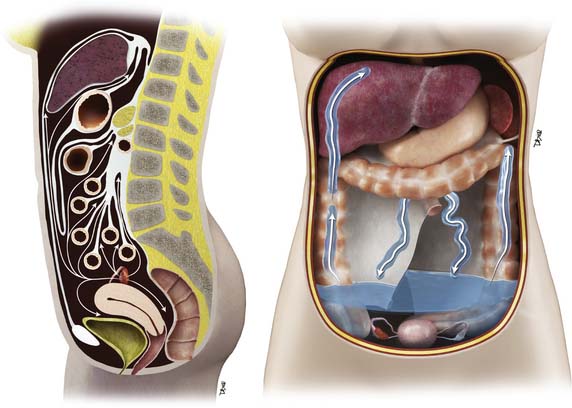

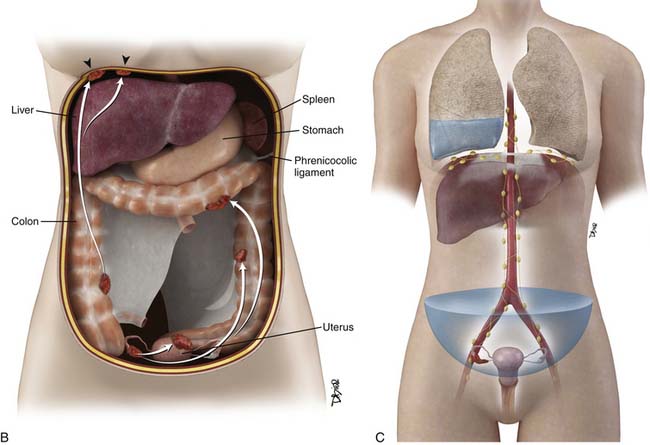

The most common mode of tumor spread in ovarian cancer is intraperitoneal dissemination (Figure 26-2), and approximately 70% of patients have peritoneal metastases at staging laparotomy. The greater omentum, right subphrenic region, and pouch of Douglas are the three most commonly involved sites found at laparotomy.43 Tumor deposits are uncommonly seen in the left subdiaphragmatic space because the inframesocolonic space is separated by the phrenicocolic ligament on the left. The malignant cells are shed from the tumor surface into the peritoneal cavity, and they follow the normal routes of peritoneal circulation. In the upright position, they will first fall into the cul-de-sac and other dependent portions of the pelvis; in the supine position, the fluid then flows into the paracolic gutters and eventually to the diaphragm.44 The fluid then flows more commonly to the right paracolic gutter, along the liver capsule, and the diaphragm.44 The peritoneal fluid then normally drains via the lymphatics of the diaphragm to the mediastinum via the internal mammary chain of lymph nodes.45,46 When these diaphragmatic lymphatics become occluded by tumor cells, the absorption of peritoneal fluid is impaired, resulting in accumulation of malignant ascites.

The lymphatic system also helps in dissemination of the ovarian cancer tumor cells. Lymphatic metastases can result from direct absorption by the lymphatic channels of the ovary versus absorption of tumor cells by the diaphragm.47 The ovaries have three pathways of lymphatic drainage. The main lymphatics follow the ovarian veins to the left para-aortic and the right paracaval lymph nodes at the level of the renal hilum and are the most common sites for metastatic adenopathy. The lymphatics of the broad ligament drain into the pelvic lymph nodes, external iliac, hypogastric, and obturator chain.18,45 Metastatic spread to the superficial and deep inguinal nodes can be seen when tumor spread occurs via the round ligaments.

Hematogenous spread of disease is rare at presentation and has been reported in up to 50% of patients at autopsy.18,48 The most common sites of hematogenous involvement are the liver followed by the lung, but other locations including the brain, bone, adrenal gland, kidney, and spleen have all been reported.18,48,49 Although most tumors may spread in this fashion, serous and clear cell cancers predominantly spread via the lymph nodes.50,51 Some aggressive tumors such as choriocarcinomas and embryonal carcinomas commonly spread hematogenously.

Staging

The most common histologic types of ovarian cancer are serous, mucinous, endometrioid, clear cell, and undifferentiated tumors. These constitute 90% of ovarian cancers and arise from the surface epithelium.20 The overall prognosis is bad when these tumors become metastatic. However, the tumors of low malignant potential, formerly called “borderline tumors,” have a better prognosis. Histopathologically, they are usually either mucinous or serous tumors.14,52 Granulosa cell tumors, dysgerminomas, immature teratomas, endodermal sinus tumors, and metastases constitute the majority of the remaining malignant ovarian tumors.20,51 Approximately two thirds of patients have advanced disease at the time of diagnosis.53 Surgical exploration is typically performed to assign a disease stage based on the FIGO criteria, debulk the tumor, and confirm tumor histology.

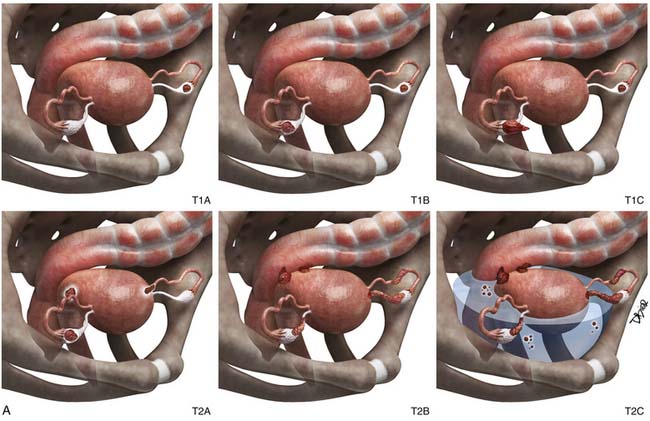

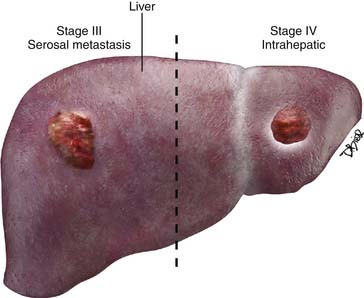

There are two staging systems: the TNM (tumor-node-metastasis) system and the worldwide used, surgically based FIGO staging system.54 The FIGO staging system is shown in Table 26-1 and Figures 26-3 and 26-4. Accurate staging is performed with a staging laparotomy, which includes hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, pelvic and para-aortic lymph node biopsies, omentectomy, peritoneal biopsies, and washings.42,55 Tumor stage is a major prognostic factor.52 The overall 5-year survival rate depends on the tumor stage at presentation.53 The 5-year survival rate in descending order is 80% for stage I disease, 50% for stage II, 30% for stage III, and 8% for stage IV disease.14 Several other factors can affect prognosis such as histologic type, tumor grade, amount of residual disease after the initial cytoreductive surgery (debulking), and patient characteristics (age and performance status).52

Table 26-1 The Current FIGO Staging of Primary Ovarian Cancer, Proposed Changes and Classification(s) by the GCIG

| CURRENT FIGO STAGING | CURRENT FIGO CLASSIFICATION |

|---|---|

| Stage I | Growth limited to the ovaries |

| Stage IA | Growth limited to one ovary; no ascites present containing malignant cells. No tumor on the external surfaces; capsules intact |

| Stage IB | Growth limited to both ovaries; no ascites present containing malignant cells. No tumor on the external surfaces; capsules intact |

| Stage IC | Tumor either stage IA or IB, but with tumor on surface of one or both ovaries; or with capsule(s) ruptured; or with ascites present containing malignant cells or with positive peritoneal washings |

| Stage II | Growth involving one or both ovaries with pelvic extension |

| Stage IIA | Extension and/or metastases to the uterus and/or tubes |

| Stage IIB | Extension to other pelvic tissues |

| Stage IIC | Tumor either stage IIA or IB, but with tumor on surface of one or both ovaries; or with capsule(s) ruptured; or with ascites present containing malignant cells or with positive peritoneal washings |

| Stage III | Tumor involving one or both ovaries with histologically confirmed peritoneal implants outside the pelvis and/or positive retroperitoneal or inguinal nodes. Superficial liver metastases equals stage III. Tumor is limited to the true pelvis, but with histologically proven malignant extension to small bowel or omentum |

| Stage IIIA | Tumor grossly limited to the true pelvis, with negative nodes, but with histologically confimed microscopic seeding of abdominal peritoneal surfaces, or histologically proven extension to small bowel or mesentery |

| Stage IV | Growth involving one or both ovaries with distant metastases. If pleural effusion is present, there must be positive cytology to allot a case to stage IV. Parenchymal liver metastasis equals stage IV |

From Lerner JP, Timor-Tritsch IE, Federman A, Abramovich G. Transvaginal ultrasonographic characterization of ovarian masses with an improved, weighted scoring system. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;170:81-85.

Patients can be understaged if a complete staging laparotomy is not performed. In more than 30% of patients, ovarian cancer is understaged at initial laparotomy; and in 77% of these cases, the tumor is presumed to be localized to the pelvis but subsequently is found to be stage III when a full staging procedure is performed.56 Incorrect staging may result in erroneous counseling about treatment options and prognosis. Sites of unsuspected disease most often include the pelvic peritoneum and tissues, ascitic fluid, para-aortic nodes, and diaphragm.57

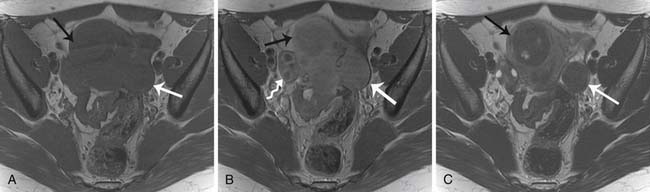

Stage II

In stage II disease, there is local extension of tumor to involve the surrounding organs. In this stage, the tumor is confined to the pelvis without upper abdominal involvement. Stage IIA disease is characterized by either direct extension of tumor to the uterus or presence of implants on the uterus or the fallopian tubes. In stage IIB disease, tumor extends to involve surrounding pelvic tissues, rectum, bladder, and peritoneum. Imaging findings that suggest local extension of tumor are loss of tissue planes between the tumor and the bladder or the colon, less than 3 mm of space between the tumor and the pelvic sidewall, and presence of displacement or encasement of iliac vessels.58 Owing to the superior soft tissue contrast resolution, direct invasion is better seen with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) than with either computed tomography (CT) or US.58

Stage III

While interpreting images, one should look carefully for subtle peritoneal thickening, nodularity, or enhancement of the peritoneal surfaces, which is an indication of peritoneal carcinomatosis.59 Presence of ascites in ovarian cancer is suggestive of peritoneal disease and aids in lesion conspicuity.60,61 The most common site of peritoneal spread of tumor is the omentum.62 This involvement may be microscopic, not visible on imaging or on visual inspection during surgery; however, it can be detected on histopathology.63 A fine reticulonodular pattern may be seen on radiology initially but is often subtle. Later, as disease progresses, there is often marked thickening resulting in omental caking. In addition, other common sites of involvement should be carefully evaluated, such as the subphrenic space, mesentery, and paracolic gutters. Coronal re-formats are usually helpful in evaluating the subdiaphragmatic regions.62

The small bowel is most commonly involved, by either serosal implants or frank bowel wall invasion, which can lead to bowel obstruction.48 This is the most common cause of morbidity in patients and has been reported in approximately 50% of autopsy cases.48 On imaging, the involved bowel usually appears thickened with resultant narrowing of the lumen. In stage III disease, along with peritoneal disease retroperitoneal, adenopathy has been reported in 27% to 44% of patients.62,64,65

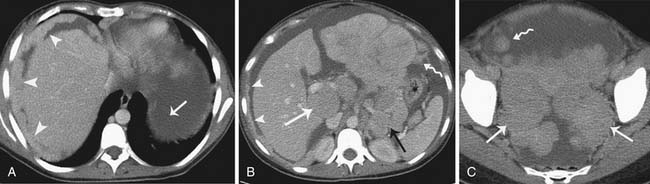

Stage IV

Stage IV disease is characterized by distant spread of tumor, which includes tumor spread to the pelvis and solid organs such as the liver. For a radiologist, it is important to differentiate implants on the liver capsule (stage III) from true parenchymal metastases (stage IV) because they are treated differently and have a different prognostic significance (see Figure 26-4). Surgically, the capsular implants are considered resectable, whereas parenchymal metastases are not. Hepatic capsular masses are usually well defined, have an elliptical shape, and may compress the liver and rarely infiltrate into it. These implants can insinuate along the falciform ligament and can be misdiagnosed as parenchymal metastases. True hepatic parenchymal metastases are usually surrounded by the liver and can have irregular margins. Depending on the origin of the primary tumor, the implants may have variable appearance on CT, MRI, and US. For example, the mucinous peritoneal implants are low in attenuation on CT scans and do not calcify. They are diffuse and insinuate between the leaves of the mesentery, bowel loops, and solid organs.14 These implants are low in attenuation and may be confused with ascites; however, these cause mass effect and scalloping of the liver capsules and solid organs. Mesenteric sides of the bowel loops get matted and subtle septations may be noted on CT. Because these implants are gelatinous, their insinuating nature makes complete resection rather difficult. It is important to know that the origin of pseudomyxoma peritonei is now believed to originate from the appendix and metastasize to the ovary.66 Thus, when pseudomyxoma peritonei is suspected, thorough evaluation and special pathologic staining should be performed to differentiate ovarian from gastrointestinal origin.

Serous cystadenocarcinoma implants are associated with microcalcifications, which are known as psammoma bodies.14,45 These implants can calcify along the peritoneal lining, and this finding has been reported in 33% of cases of metastatic serous tumors.

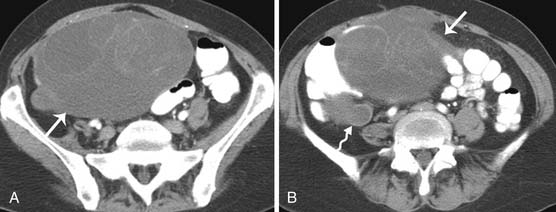

In gastric cancers and colorectal cancers, the tumor’s malignant cells may deposit on the ovaries and result in large ovarian masses that can be mistaken for primary ovarian tumors (Figures 26-5 and 26-6). These tumors may present with peritoneal carcinomatosis and potentially can be confused with metastatic ovarian carcinoma.59 This cannot be differentiated by imaging. In situations like this, in which bilateral adnexal masses and peritoneal disease are present, the radiologist should make a thorough search for the gastrointestinal tract primary, and special stains should be performed on histopathology in order to differentiate one from the other. Other tumors that can present in a similar manner are mesothelioma and papillary serous carcinoma of the peritoneum.51 Although rare, in the right clinical setting, infectious or inflammatory processes such a tuberculous peritonitis should be considered.51

Key Points Federation of gynecology and obstetrics staging

• Stage I is limited to the ovaries. It has a 5-year survival rate of 73%. Treatment is surgery with or without postoperative chemotherapy.

• Stage II involves the ovaries with pelvic extension. It has a 5-year survival rate of 45%. Treatment is surgery with postoperative chemotherapy.

• Stage III involves the ovaries with metastases outside the pelvis and/or lymphadenopathy. It has a 5-year survival rate of 30%. Treatment is surgery with postoperative chemotherapy.

• Stage IV has distant metastases. It has a 5-year survival rate of 5%. Treatment is neoadjuvant chemotherapy and/or surgery.

Imaging

Role of Imaging in Diagnosing Primary Neoplasms

Primary Tumor

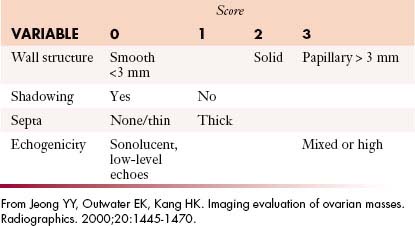

US has an important role in the initial evaluation of a suspected adnexal mass.67,68 When the patient’s menopausal status is taken into account, the CA125 levels and the imaging findings can help distinguish a benign from a malignant mass. This is called the risk malignancy index (RMI) (Table 26-2).69 A score of 1 is given to a premenopausal female and a 3 is given to a postmenopausal woman. The total score greater than 200 has high specificity of diagnosing malignancy.70

Table 26-2 Risk Malignancy Index Based on the Product of Ultrasound Findings, CA-125, and the Menopausal Status

Epithelial tumors usually present as large cystic masses on imaging.51,71 The following features are suggestive of malignancy: septations greater than 3 mm; mural nodules or nonfatty solid components; homogeneous, solid masses or complex masses with cystic/solid areas; cystic masses greater than 10 cm in diameter; nodularity extending from the walls of a cystic mass; or soft tissue thickening.51,68 Although these features are useful, absolute characterization of the mass and prediction of histology are not possible with US or any other imaging technique. Certain features may be able to predict histology of the tumor; large masses containing mural nodules and thick septations are suggestive of cystic adenocarcinomas. Serous cystic tumors are usually unilocular and may mimic physiologic cysts. However, when these unilocular cysts have papillary projections along the cystic wall, it is suggestive of a carcinoma and may be seen on US, CT, or MRI (Figure 26-7).

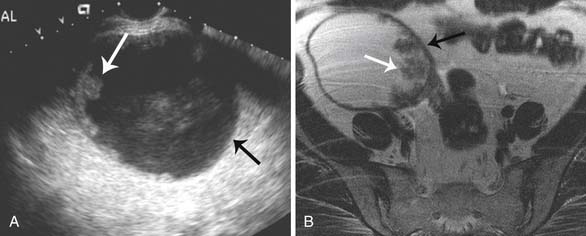

The mucinous tumors are multilocular, can have an echogenic appearance due to the presence of mucin or internal hemorrhage on the US, and can have variable signal within the locules (“stained-glass” appearance) on MRI. Most of these tumors are benign (Figure 26-8).14,16 Brenner’s tumors are hypoechoic on US and can have calcifications within them. They are indistinguishable from uterine fibroids. Teratomas may be cystic and may contain an eccentric echogenic fat nodule or may be completely cystic, containing fluid-fluid levels. The morphologic information provided by gray-scale imaging is complemented by color flow Doppler techniques. The introduction of harmonics and unique pulse sequences has improved signal-to-noise ratios and structural conspicuity, and the potential use of sonographic intravenous contrast agents has helped more accurately detect and quantify vascularity and blood flow. Contrast agents may significantly improve the diagnostic ability of US and identify early microvascular changes that are known to be associated with early-stage ovarian cancer.72 Some of the features that predict malignancy on color Doppler are detection of central blood flow within the solid components, low resistive index waveforms less than 0.4 and a pulsatility index of 1 because ovarian cancers tend to have low-resistance flow from tumor neovascularity and arteriovenous shunting.43 However, there is some overlap between the flow characteristics of benign and malignant lesions.68,73 Literature suggests that adding color Doppler to gray-scale to morphologic information increases the specificity from 82% to 97% and the positive predictive value (PPV) from 63% to 97%.74 Even though US is helpful in characterizing pelvic masses, its accuracy to stage cancer is low at 60% or less.75 The CT appearance of ovarian tumors also varies with the histology of the tumor. The overall accuracy in the detection of ovarian masses approaches 95%, but its specificity in distinguishing between benign and malignant lesions ranges from 66% and 94%.43,76 Morphologic findings such as cystic masses with septations, nodules, vegetations, or papillary projections and necrosis within solid masses suggest malignancy as with US. However, the imaging features of ovarian masses on CT are also not entirely specific.77 Recent studies indicate that thin-section CT is able to distinguish a benign from a malignant ovarian neoplasm with an accuracy of 89%.78 Several early studies have addressed the value of CT in preoperative staging of ovarian cancer with reported accuracies of 70% to 90%.58,79–82

Many adnexal lesions, particularly endometriomas and cystic teratomas, are still classified as indeterminate on US despite advances in US technology; in these situations, MRI can be used as a problem-solving tool. MRI is superior to CT in characterizing adnexal masses because it provides excellent tissue characterization owing to its ability to detect fat and blood products.83,84 MRI has overall accuracy of distinguishing benign from malignant ovarian masses of 83% to 91%.84,85 The MRI features of malignancy—such as cyst wall irregularity, intramural nodules, papillary projections, septations, complex masses containing solid and cystic components, large lesions, and early enhancement on dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI studies—are similar to those seen on CT and US. Ancillary findings such as ascites, peritoneal disease, or adenopathy help clinch the diagnosis of malignancy.85 Serous epithelial neoplasms usually appear as unilocular masses and can have mural nodules that may enhance. They can also appear as simple cysts on US, CT, or MRI.

On CT imaging, mature teratomas have fat attenuation within the cyst and may have calcification within the cyst wall or within the cyst itself. On MRI, the cyst may have high signal intensity on T1-weighted imaging (T1WI) due to the sebaceous component, which is similar to that of the subcutaneous fat. On T2-weighted imaging (T2WI), the signal intensity of the sebaceous component is variable and may be similar to that of fat (Figure 26-9).

Choriocarcinomas

Choriocarcinomas contain hemorrhagic components and may have a high signal on T1WI. Fibromas and fibrothecomas have fibrous components that have a low signal on T1WI and T2WI and can mimic fibroids of the uterus (Figure 26-10).

Although PET/CT is not widely used, its ability to characterize ovarian masses as benign from malignant based on metabolic activity is controversial. Hypermetabolism in an ovarian lesion in a premenopausal female can represent a benign lesion such as corpus luteum cysts; however, ovarian uptake in postmenopausal women needs further evaluation with either a US or an MRI. Frequently, uptake in the ovaries in a premenopausal female may be physiologic. Whole body fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG)-PET scanning is not routinely used in the diagnosis and staging of primary ovarian cancer. Early studies showed sensitivities and specificities of 83% to 86% and 54% to 86%, respectively.86–88 In a study by Rieber and coworkers,84 FDG-PET had a lower sensitivity and specificity than MRI and endovaginal US, and they thought it was due to the presence of a high percentage of low–malignant potential tumors and early-stage ovarian cancers whereas the earlier studies showed higher sensitivities owing to a greater proportion of advanced-stage tumors.86–88 Borderline tumors (low malignant potential) and early-stage carcinomas may not demonstrate hypermetabolism because only a small amount of transformed tissue is present for glucose uptake.

Key Points Imaging

• US can help determine masses of ovarian origin.

• US can help distinguish malignant versus benign lesions, but there is a considerable overlap between the two and MRI can be beneficial.

• Color Doppler provides useful information for determination of malignancy in a proper clinical setting.

• Summary of the key imaging features in the differential diagnosis of primary tumors16

Imaging Lymphadenopathy and Peritoneal Disease

Lymphadenopathy

Cross-sectional imaging techniques such as CT and MRI rely on nodal size as the primary criterion for determining the presence of metastatic disease within lymph nodes. Nodal spread of disease still remains a challenge to detect. The overall reported accuracy for detection of metastatic disease in lymph nodes is approximately 85%. Large nodal metastases can easily be detected with CT or MRI (Figure 26-11). The major limitation of CT and MRI is their dependence on size to determine nodal involvement. Therefore, although an enlarged lymph node is likely to be involved, it is not possible to exclude metastatic disease in a normal-sized lymph node. Using a size threshold of greater than 1 cm in short axis to define abnormal lymph nodes, the sensitivity and specificity of preoperative CT for nodal staging are 50% and 92% and those of MRI were 83% and 95%, respectively.58

Metabolic imaging with FDG-PET is an alternative for detecting metastatic lymph nodes as well as recurrence in patients with pelvic malignancies. PET, in contrast, relies on the increased metabolic activity in lymph nodes, can detect metastases in normal-sized lymph nodes, and has a reported sensitivity of 50% to 82% and a specificity of 92% to 95%.89 The presence of lymph node metastases in ovarian cancer is an important prognostic feature. The frequency of nodal metastases in a patient with stages I and II disease is close to 17% and increases to 37% in advanced stages.90 Superior diaphragmatic adenopathy is detected in approximately 15% of patients with advanced ovarian cancer and is usually associated with a grave prognosis.91

Peritoneal Disease

Computed Tomography

Currently, CT is the modality used for staging ovarian cancer because it is widely available. CT examination is used to evaluate the primary tumor site and the extent of disease and potential sites of peritoneal implants, lymphadenopathy, and solid organs. CT can depict tumor implants larger than 1 cm (see Figure 26-11) throughout the abdomen and pelvis, with a sensitivity of 85% to 93% and a specificity of 91% to 96%.62,92 However, the CT sensitivity decreases to 25% to 50% in detecting implants measuring 1 cm or smaller.62 Opacifying the gastrointestinal tract helps distinguish peritoneal implants from bowel and is useful for determining the presence of bowel invasion. It is, however, important to know that calcified metastases may be obscured by contrast, and thus, some believe in using water as a contrast agent.60

Intravenous contrast is useful to define the solid organs in the abdomen and pelvis and more clearly delineate peritoneal deposits. The detection of peritoneal tumor deposits is largely dependent on their location and their size. Ascites and lymphadenopathy in the pelvis and retroperitoneum are well demonstrated by CT, and the presence of ascites or calcification can increase conspicuity of the metastases.77 The hemidiaphragms are difficult to evaluate, and axial imaging can miss small plaquelike deposits. Thin-section imaging allows the data to be manipulated, the images can be reconstructed in the coronal and sagittal dimensions, and these subdiaphragmatic lesions can be better seen.60 These reconstructed images also aid in delineation of peritoneal tumor deposits from the unopacified bowel loops. The presence of isolated splenic recurrence is an important finding and can be detected by CT; then splenectomy can be performed with improved long-term survival.93,94

Studies have been performed with intraperitoneal instillation of iodine intravenous contrast that suggest that the sensitivity of detecting peritoneal disease was superior to that of standard CT scans.95 However, this technique fails to detect flat peritoneal metastases and, in patients with prior abdominal surgery, had a low sensitivity; such studies are not currently performed.96 Conventional contrast-enhanced CT has a sensitivity of 63% to 92% and a specificity of 82% to 96%; in detection of peritoneal involvement, it has a negative predictive value of 20% and a sensitivity of detecting nodules smaller than 0.5 cm of 28%.59,62,95,97,98

Ultrasound

US is operator dependent.99,100 Bowel gas can obscure pathology and make complete evaluation of all possible areas of peritoneal involvement difficult, even in the hands of an experienced sonologist. MRI and CT are superior to US, especially in evaluation of the subdiaphragmatic and hepatic surfaces. A study performed by Tempany and colleagues62 found that the sensitivity of Doppler US in the detection of peritoneal metastases is lower at 69% compared with 95% for MRI, and 92% for spiral CT in patients with advanced cancer (stages III and IV).

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI has staging accuracy similar to that of both conventional58 and spiral CT.83 MRI also helps identify invasion of pelvic organs owing to its superior soft tissue contrast resolution.58 Technique optimization includes the use of oral and intravenous contrast agents to define bowel; the use of fat suppression and fast sequences that may be performed with breathholding, fasting, and the use of pharmacologic agents to decrease bowel motion62,83; and aids in visualization of the bowel surface, peritoneum, and adnexa.

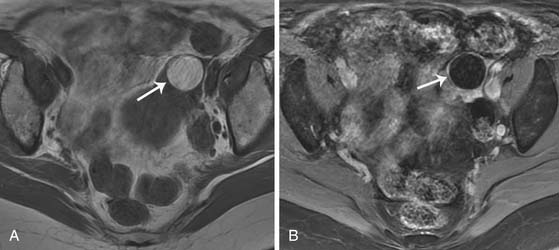

There is no statistical difference in the accuracy between CT and MRI in determining the location, distribution, and measuring the size of implants in stages III and IV disease.62 Compared with spiral CT, MRI is able to detect small or equivocal peritoneal implants.101,102 However, mesenteric and bowel wall implants are still probably better detected with CT because bowel motion is still a problem on MRI and calcified deposits are more clearly seen with CT. The performance of MRI deteriorates compared with CT when there is no ascites. Given the greater availability and ease of performance, CT is considered the modality of choice for staging ovarian cancer.71

Oral barium acts as a negative contrast in the bowel on T1WI, and studies have shown that use of dilute barium in conjunction with intravenous contrast-enhanced MRI improves detection of serosal and omental implants compared contrast-enhanced CT.103

Respiratory-gated fast spin echo T2WI helps in delineation of pelvic anatomy. Pre- and post–three-dimensional dynamic imaging is performed through the abdomen and pre- and postcontrast T1-weighted fat-suppressed imaging through the pelvis is recommended in all cases. The contrast-enhanced study not only helps characterize the tumor but also improves detection of peritoneal and omental implants. Although peritoneal enhancement and nodularity are sensitive for detection of peritoneal malignancy, it is not specific.104–106 Compared with unenhanced T1WI and T2WI sequences, gadolinium-enhanced T1WI help identify small peritoneal implants on free peritoneal surface and bowel serosa.59,107 Coronal and axial fast imaging employing steady state acquisition (FIESTA) sequence can freeze bowel and help identify implants.108

Imaging can identify disease that can complicate primary surgical debulking or is unresectable. Usually, the disease is considered inoperable when there is invasion of the pelvic sidewall, rectum, sigmoid colon, or bladder or when the tumor deposits are greater than 1 to 2 cm in the porta hepatis, intersegmental fissure of the liver, lesser sac, gastrosplenic ligament, subphrenic space, root of mesentery, and presacral space; suprarenal adenopathy; and hepatic (parenchymal), pleural, or pulmonary metastases.58,109,110

Positron-Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography

Although PET/CT has a limited role in characterizing ovarian masses, it is helpful in staging of ovarian cancer.111,112 FDG-PET has limited ability to visualize small (<1 cm) tumor deposits. False-positive findings may be seen in inflammatory processes, corpus luteum cysts, and physiologic gastrointestinal activity84 and can be unsuitable for ovarian lesion characterization.84 FDG-PET and PET/CT can be used in the setting of recurrent disease, when results of CT and MRI are negative but tumor markers are increasing.113–118 PET/CT scanning allows better restaging than CT alone and can induce a change in clinical management in patients with suspected ovarian carcinoma recurrence in the setting of increased CA125 and can migrate the stage in advanced disease.119 PET/CT can help in optimizing the selection of patients for site-specific treatment, including radiation treatment planning, and aids in selection of optimal surgical candidates.120,121

Key Points Utility of imaging

• Imaging has its limitations for distinguishing benign from malignant disease, use of RMI may increase the specificity to 97%. No imaging modality can detect clinically important microscopic disease, and therefore, negative imaging findings do not obviate the necessity for complete surgical staging.

• CT can be used to assess the extent of disease, sites of inoperable disease, and cases in which patients may optimally be treated with preoperative chemotherapy rather than primary cytoreduction.

• Radiologic staging can guide subspecialty referral. For example, for stage III disease, the patient should be referred directly to a gynecologic oncologist for optimal cytoreduction.

• CT can reliably detect peritoneal nodules greater than 1 cm and has the ability to stage ovarian cancer.

• Uptake in the ovary in postmenopausal women should be further evaluated to exclude malignancy.

• Uptake in the ovaries in a premenopausal female is usually physiologic.

Recurrent Disease

Computed Tomography

CT has a low sensitivity for detection of recurrent peritoneal carcinomatosis and lymphatic metastasis. However, despite low sensitivity of CT, it may still have the potential role for preoperative recurrent ovarian cancer patients because it can detect nonresectable recurrent disease.122 The significant indicators of tumor nonresectability were presence of hydronephrosis and pelvic sidewall invasion, whereas the presence of small bowel obstruction, nodal or perihepatic liver metastasis, ascites, and the level of CA125 were not strong indicators of tumor nonresectability.

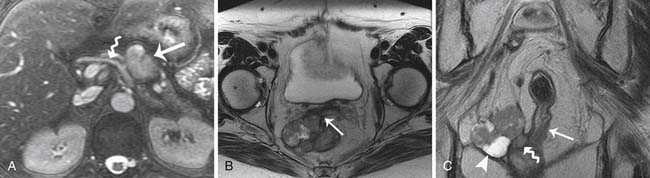

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

The ability of MRI in detecting recurrence of ovarian cancer has a reported 90% sensitivity, 88% specificity, and 89% accuracy.123 With increasing serum CA125 levels and negative abdominopelvic CT scan, the sensitivity and accuracy of MRI were 84% and the specificity was 100%.124,125 Although studies suggest that there is no statistically significant difference between CT and MRI for the depiction of recurrent ovarian cancer,126 MRI may, however, be better owing to its better spatial resolution to assess for resectability of recurrent disease (Figure 26-12).

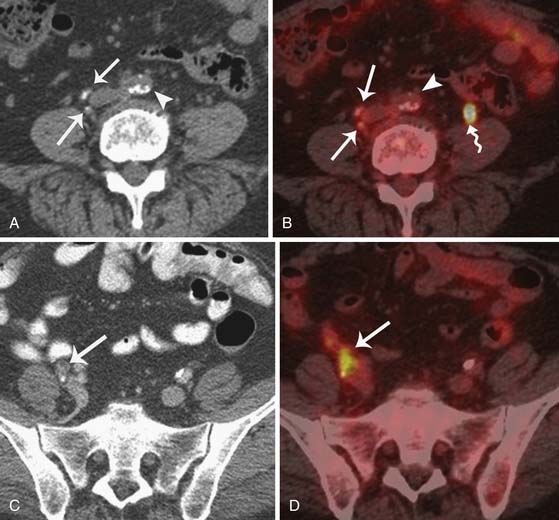

Positron-Emission Tomography Alone and Positron-Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography

The use of combined PET/CT for detecting recurrent ovarian cancer was first described by Makhija and associates in 2002.127 They reported that PET/CT correctly identified surgically confirmed tumor masses, ranging in size from 3.0 to 8.0 cm, in five of seven patients with recurrent ovarian or fallopian tube cancer. PET has the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy for the diagnosis of recurrent ovarian cancer of 84.6%, 100%, and 86.2%, respectively, and in patients in whom the suspicion of recurrence was based on a rise of serum CA125, the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy were 90.4%, 100%, and 91.2%, respectively. PET/CT may help in assessing metabolic activity in suspected recurrence as seen in CT in the setting of small volume metastases or in patients with serous tumors developing calcified metastases to the peritoneum or lymph nodes (Figure 26-13).

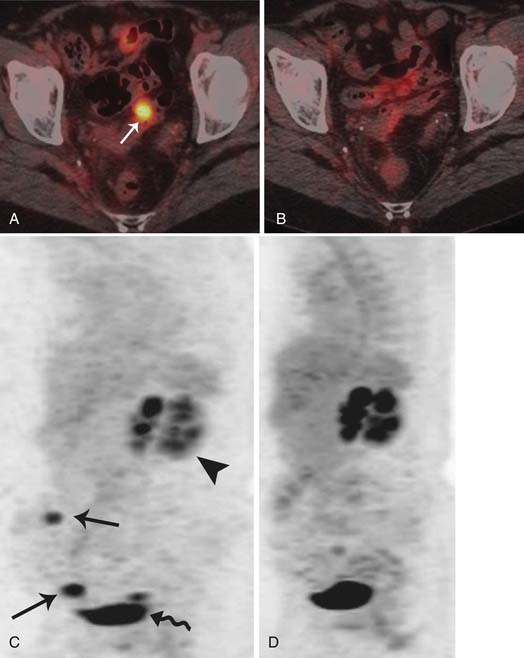

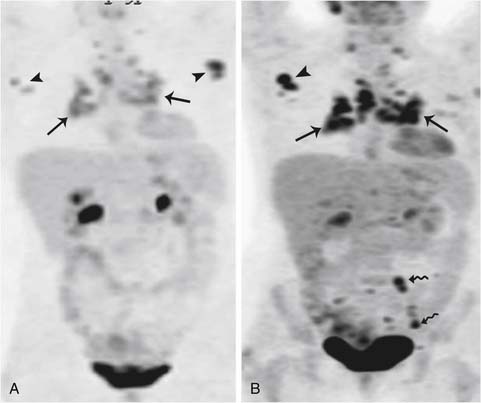

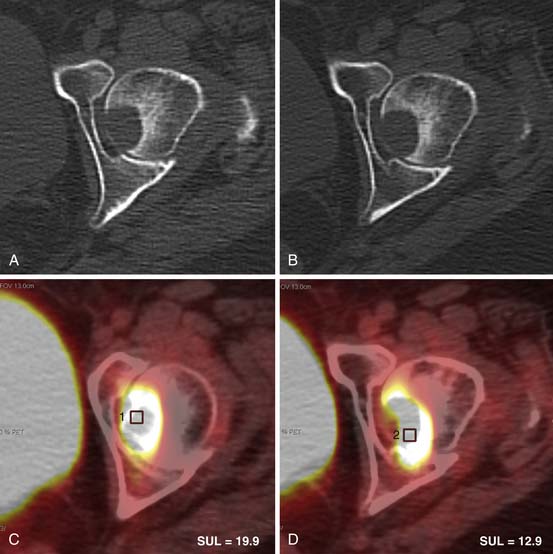

A recent meta-analysis suggested that the difference between PET alone and PET/CT in detecting recurrence was slight.128 Although compared with PET alone, PET/CT can provide not only metabolism information but also sufficient morphologic information, so PET/CT might be helpful for selecting patients who may derive a significant survival benefit from optimal debulking and finding an optimal surgical strategy for those patients. Given all this, a recent prospective trial showed that there is no survival difference even if the recurrent tumor is detected and treated early because imaging and scheduled follow-up do not seem to improve the clinical outcome of patients who ultimately develop recurrent disease.129 PET/CT is being used to assess response to therapy because it does provide functional as well as morphologic information regarding disease status. At our institution, PET/CT is performed at the time of recurrence followed by CT scans and, if the disease is stable over time during chemotherapy, a PET/CT may be performed to assess its functional status; eventually, the chemotherapy is stopped if the disease is not metabolically active (Figures 26-14 and 26-15).

Surveillance

Tumor Markers

CA125 is expressed by the surfaces of epithelial cells; those are found in approximately 80% of epithelial ovarian carcinomas and can be used for screening of ovarian cancer. However, patients with cirrhosis, pancreatic cancer, endometriosis, pelvic inflammatory disease and with other malignancies can also have elevated levels of CA125130 and the PPV of screening with serum marker is low at 1%.131

Tumor Markers and Imaging for Detecting Recurrent Disease

Serum CA125 is the most widely used method to detect recurrence and monitor response to treatment and is a sensitive tumor marker.132,133 The rise of CA125 level above the upper limit of normal (35 U/mL) in patients with normalization is thought to suggest recurrent disease, although elevated CA125 does not justify initiation of treatment in asymptomatic patients.134 Rising serum CA125 levels may precede the clinical detection of relapse in 56% to 94% of cases with a median lead time of 3 to 5 months.135 In 3% of patients previously treated for ovarian malignancy, CA125 may be elevated, with no evidence of recurrent cancer.136 The absolute value of CA125 has not been linked to a particular pattern of recurrence,137 although in the absence of clinically or radiographically demonstrable recurrence, the significance of a rising serum CA125 level has not yet been determined.

Key Points Surveillance

• CA125 is the tumor marker used for surveillance in epithelial tumors.

• Treatment of disease cannot be based on elevation of tumor marker alone without radiologic evidence of disease in an asymptomatic patient.

• Cross-sectional imaging can be used to assess for recurrent disease in patients with elevated tumor markers.

Treatment

Surgery

For most patients with advanced disease, the goal of surgery is to provide optimal tumor reduction with removal of all visible tumor. This generally includes a total abdominal hysterectomy, removal of ovarian masses, omentectomy, and excision of any other tumor implants. Whereas removal of bulky tumors certainly provides symptomatic relief for the patients, Munnel138 was the first to show that “maximal surgical effort” significantly improves survival (28% vs. 9%) compared with “partial removal” or “biopsy alone.” Over the years, several investigators have published reports that show a significant survival advantage for patients with optimal surgical cytoreduction.42,56,139 Even among patients who have undergone suboptimal tumor reduction (residual tumor > 1 cm), Hoskins and coworkers139 showed an improved survival in patients with 1 to 2 cm of residual disease compared with those with greater than 2 cm of residual disease (P < .01). Among patients with stage IV disease, several retrospective reports show a statistically significant survival advantage in patients with small-volume residual tumor. Finally, aggressive primary cytoreductive operations are associated with minimal morbidity and mortality when performed by experienced surgeons. All these data have led the National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference on Ovarian Cancer to conclude in 1994 that “aggressive” attempts at cytoreductive surgery as the primary management of ovarian cancer will improve the patient’s opportunity for long-term survival.140

Chemotherapy

Surgery alone, however, is rarely curative for patients with advanced ovarian cancer. Currently, the standard of care consists of a combination of paclitaxel and carboplatin. This regimen can be administered in an outpatient setting, with area under the curve (AUC) dosing used for carboplatin and paclitaxel given as a 3-hour infusion. The combination is well tolerated, with fewer than 2% of the cycles associated with grade 4 thrombocytopenia or febrile neutropenia, and is associated with an overall response rate of approximately 75%.141 Recently, the Gynecologic Oncology Group conducted a randomized, phase 3 trial that compared intravenous paclitaxel plus cisplatin with intravenous paclitaxel plus intraperitoneal cisplatin and paclitaxel in patients with stage III ovarian cancer.142 Only 42% of the patients in the intraperitoneal therapy group completed six cycles of the assigned therapy, but the median duration of progression-free survival in the intravenous therapy and intraperitoneal therapy groups was 18.3 and 23.8 months, respectively (P = .05 by the log-rank test). The median duration of overall survival in the intravenous therapy and intraperitoneal therapy groups was 49.7 and 65.6 months, respectively (P = .03 by the log-rank test). Based on these findings, several groups have advocated the use of intraperitoneal chemotherapy as the preferred adjuvant treatment for patients following optimal tumor reductive surgery.

Key Points Surgery and chemotherapy

• Primary cytoreductive surgery is the mainstay of treatment and consists of total abdominal hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, omentectomy, and lymphadenectomy to the level of the renal hilum.

• Presence of subdiaphragmatic implants limits suboptimal cytoreduction.

• Implants invading pelvic sidewall, rectum, sigmoid colon, or bladder.

• Tumor deposits are greater than 1 to 2 cm in the porta hepatis, intersegmental fissure of the liver, lesser sac, gastrosplenic ligament, subphrenic space, root of mesentery, and presacral space; suprarenal adenopathy; and hepatic (parenchymal), pleural, or pulmonary metastases.

• Mesentery and presacral space; suprarenal adenopathy; and hepatic (parenchymal), pleural, or pulmonary metastases.

• Intraperitoneal chemotherapy cisplatin and paclitaxel is the preferred adjuvant treatment for patients after optimal tumor reductive surgery.

Radiation Therapy

The role of radiation therapy in the management of ovarian cancer has evolved dramatically since the early 1960s and continues to be refined. Before the development of modern chemotherapy agents, radiation therapy played an important role in treatment of patients with early or completely resected disease. In the 1970s, two randomized trials compared whole abdominal radiotherapy (WAR) versus pelvic radiation therapy combined with an alkylating agent (melphalan or chloramucil).143 The studies demonstrated that WAR could produce cures and suggested that the effectiveness of WAR was comparable with or perhaps even better than the single-agent chemotherapy available at the time. Intraperitoneal administration of radioactive phosphorus (32P) may also be an effective treatment in carefully selected patients with minimal disease but should not be combined with pelvic radiation therapy because of a high risk of bowel complications.143 In the 1980s and 1990s, the advent of more effective chemotherapy agents such as cisplatin and the taxanes led many clinicians to abandon the use of radiation therapy in the curative management of ovarian cancer. During this time, some investigators used WAR as a treatment for incomplete responders to platinum-based chemotherapy. However, acute side effects (particularly hematologic) were substantial and most investigators reported poor overall disease control rates.144–147 Although there were isolated reports of long-term survival of patients treated with postchemotherapy WAR, this approach is not commonly used today.

Although the role of radiation therapy in the curative treatment of ovarian cancer is relatively minor today, local treatment of persistent or recurrent disease in the pelvis or primary echelon lymph nodes can result in long disease-free intervals in carefully selected patients.147,148 Modern, highly conformal radiation therapy techniques facilitate administration of tumoricidal doses with minimized risk to adjacent critical structures.

Radiation therapy is also a highly effective tool in the management of tumor-related symptoms from uncontrolled local disease, painful bone metastases, or other symptomatic lesions.149,150 A variety of radiation schedules may be used according to the nature of the lesion and life expectancy of the patient. In some cases, one or two treatments of 8 to 10 Gy can provide very effective palliation; if two treatments are given, they are generally spaced 1 month apart. Other common fractionation schedules include 20 Gy in 5 fractions or 30 Gy in 10 fractions. With these regimens, the risk of serious radiation-related complications is small.

Investigational Therapy

Several investigational agents are being studied in the relapsed setting. Bevacizumab is humanized antibodies that recognizes and deactivates vascular endothelial growth factor, an angiogenic factor often secreted by ovarian cancer cells. As a single agent, bevacizumab was shown to induce responses in 18% of patients with relapsed ovarian cancer who are either platinum-sensitive or platinum-resistant, and 39% of patients had progression-free survival at 6 months.151 It can cause proteinuria, hypertension, and bleeding and may result in other uncommon, but potentially life-threatening, side effects, such as arterial thromboembolism, wound healing complications, and gastrointestinal perforation or fistulae.152 The risk of bowel perforation with bevacizumab in the recurrent ovarian cancer setting may be related to prior multiple treatment regimens, radiographic evidence of bowel wall involvement by tumor, or the presence of bowel obstruction.153 Other investigational agents with reported activity in platinum-sensitive (and, to a lesser degree, platinum-resistant) disease include ET743 (trabectedin), halichondrin B, pertuzumab, and epothilones. Her-2/neu is usually not overexpressed in ovarian cancer, and this limits the use of humanized monoclonal antibodies such as trastuzumab.154 At present, none of these agents are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for treating patients with relapsed ovarian cancer, and their definitive significance needs to be better defined.

Conclusion

Key Points Overall review of ovarian cancer

• Ovarian cancer is the most common cause of death from cancer in women with gynecologic malignancy and results in 5% of overall deaths due to cancer.

• Risk factors identified are hormonal, genetic, and environmental.

• Variety of histologically different ovarian cancers are present that have different ages of presentation, pathways of dissemination, tumor markers, and prognosis.

• Epithelial tumors compose the majority of ovarian cancers and usually present at an advanced stage.

• Sex cord tumors occur in the reproductive age or the postmenopausal age group and can produce estrogen or testosterone depending on their origin.

• Usually, ovarian cancers produce CA125, whereas germ cell neoplasms produce alpha-fetoprotein and β-hCG.

• The most common method of spread of epithelial ovarian tumor is via peritoneal dissemination.

• Staging of ovarian tumor is based on FIGO staging, which consists of a staging laparotomy, in which the patient undergoes total abdominal hysterectomy–bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, pelvic lymphadenectomy, and omentectomy.

• Surgical cytoreduction for stages II and IV disease can be quite complex, and in some cases, macroscopic disease may be left behind. More importantly, miliary or microscopic implants cannot be surgically removed and, therefore, the role of adjuvant chemotherapy is critical.

• US, CT, and MRI can help characterize adnexal masses, although there is considerable overlap between benign and malignant lesions.

• CT is the modality used to stage intra-abdominal and pelvic disease as well as detect recurrence.

• MRI and CT are equally accurate in the staging of abdominal and pelvic disease.

• PET/CT can detect disease above the diaphragm and can help in assessing response to therapy.

• Imaging can help assess residual disease after primary cytoreductive surgery and detect recurrent disease.

1. Siegel R., Ward E., Brawley O. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;2011(61):212-236.

2. Bristow R.E., Duska L.R., Lambrou N.C., et al. A model for predicting surgical outcome in patients with advanced ovarian carcinoma using computed tomography. Cancer. 2000;89:1532-1540.

3. Holschneider C.H., Berek J.S. Ovarian cancer: epidemiology, biology, and prognostic factors. Semin Surg Oncol. 2000;19:3-10.

4. Berchuck A., Schildkraut J.M., Marks J.R., et al. Managing hereditary ovarian cancer risk. Cancer. 1999;86:2517-2524.

5. NIH consensus conference. Ovarian cancer. Screening, treatment, and follow-up. NIH Consensus Development Panel on Ovarian Cancer. JAMA. 1995;273:491-497.

6. Godwin A.K., Schultz D.C., Hamilton T.C., Knudson A.G.Jr. Oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. In: Hoskins W.J., Perez C.A., Young R.C. Principles and Practice of Gynecologic Oncology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1997:107-148.

7. Chen X., Aravindakshan J., Yang Y., et al. Early alterations in ovarian surface epithelial cells and induction of ovarian epithelial tumors triggered by loss of FSH receptor. Neoplasia. 2007;9:521-531.

8. Fathalla M.F. Incessant ovulation—a factor in ovarian neoplasia? Lancet. 1971;2:163.

9. Chene G., Penault-Llorca F., Le Bouedec G., et al. Ovarian epithelial dysplasia after ovulation induction: time and dose effects. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:132-138.

10. Daly M.B. The epidemiology of ovarian cancer. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1992;6:729-738.

11. Hall H.I., Tung K.H., Hotes J., et al. Regional variations in ovarian cancer incidence in the United States, 1992-1997. Cancer. 2003;97:2701-2706.

12. Chen V.W., Ruiz B., Killeen J.L., et al. Pathology and classification of ovarian tumors. Cancer. 2003;97:2631-2642.

13. Przybora L.A. International classification of ovarian neoplasms elaborated by the WHO Commission in 1971 [in Polish]. Patol Pol. 1974;25:203-211.

14. Wagner B.J., Buck J.L., Seidman J.D., et al. From the archives of the AFIP. Ovarian epithelial neoplasms: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 1994;14:1351-1374. quiz 1375–1376

15. Boger-Megiddo I., Weiss N.S. Histologic subtypes and laterality of primary epithelial ovarian tumors. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;97:80-83.

16. Jung S.E., Lee J.M., Rha S.E., et al. CT and MR imaging of ovarian tumors with emphasis on differential diagnosis. Radiographics. 2002;22:1305-1325.

17. Outwater E.K., Huang A.B., Dunton C.J., et al. Papillary projections in ovarian neoplasms: appearance on MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1997;7:689-695.

18. Kawamoto S., Urban B.A., Fishman E.K. CT of epithelial ovarian tumors. Radiographics. 1999;19(Spec No):S85-S102. quiz S263–S264

19. Serov S.F., Scully R.E., Sobin L.H. Histological typing of ovarian tumours. In International Histological Classification of Tumours, 2nd ed., Geneva: WHO; 1973:17-54.

20. Scully R.E., Young R.H., Clement P.B. Tumors of the ovary, maldeveloped gonads, fallopian tube, and broad ligament. In: Atlas of Tumor Pathology. Washington DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 1999.

21. Scully R.E. World Health Organization classification and nomenclature of ovarian cancer. Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1975;42:5-7.

22. Seldenrijk C.A., Willig A.P., Baak J.P., et al. Malignant Brenner tumor. A histologic, morphometrical, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural study. Cancer. 1986;58:754-760.

23. Silverberg S.G. Brenner tumor of the ovary. A clinicopathologic study of 60 tumors in 54 women. Cancer. 1971;28:588-596.

24. Oh S.N., Rha S.E., Jung S.E., et al. Transitional cell tumor of the ovary: computed tomographic and magnetic resonance imaging features with pathological correlation. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2009;33:106-112.

25. Imaoka I., Wada A., Kaji Y., et al. Developing an MR imaging strategy for diagnosis of ovarian masses. Radiographics. 2006;26:1431-1448.

26. Vereczkey I., Tóth E., Orosz Z. Diagnostic problems of ovarian mucinous borderline tumors [in Hungarian]. Magy Onkol. 2009;53:127-133.

27. deSouza N.M., O’Neill R., McIndoe G.A., et al. Borderline tumors of the ovary: CT and MRI features and tumor markers in differentiation from stage I disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184:999-1003.

28. Wong H.F., Low J.J., Chua Y., et al. Ovarian tumors of borderline malignancy: a review of 247 patients from 1991 to 2004. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2007;17:342-349.

29. Tulpin L., Rouzier R., Morel O., et al. Borderline ovarian tumors: an update [in French]. Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2008;36:422-429.

30. Smith H.O., Berwick M., Verschraegen C.F., et al. Incidence and survival rates for female malignant germ cell tumors. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:1075-1085.

31. Tewari K., Cappuccini F., Disaia P.J., et al. Malignant germ cell tumors of the ovary. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:128-133.

32. Talerman A. Germ cell tumors of the ovary. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 1997;9:44-47.

33. Gershenson D.M., Del Junco G., Copeland L.J., et al. Mixed germ cell tumors of the ovary. Obstet Gynecol. 1984;64:200-206.

34. Gershenson D.M. Management of ovarian germ cell tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2938-2943.

35. Comerci J.T.Jr., Licciardi F., Bergh P.A., et al. Mature cystic teratoma: a clinicopathologic evaluation of 517 cases and review of the literature. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;84:22-28.

36. Brammer H.M.3rd, Buck J.L., Hayes W.S., et al. From the archives of the AFIP. Malignant germ cell tumors of the ovary: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 1990;10:715-724.

37. Outwater E.K., Siegelman E.S., Hunt J.L. Ovarian teratomas: tumor types and imaging characteristics. Radiographics. 2001;21:475-490.

38. Outwater E.K., Wagner B.J., Mannion C., et al. Sex cord-stromal and steroid cell tumors of the ovary. Radiographics. 1998;18:1523-1546.

39. Tsuji T., Catasus L., Prat J. Is loss of heterozygosity at 9q22.3 (PTCH gene) and 19p13.3 (STK11 gene) involved in the pathogenesis of ovarian stromal tumors? Hum Pathol. 2005;36:792-796.

40. Roth L.M., Anderson M.C., Govan A.D., et al. Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors: a clinicopathologic study of 34 cases. Cancer. 1981;48:187-197.

41. de Waal Y.R., Thomas C.M., Oei A.L., et al. Secondary ovarian malignancies: frequency, origin, and characteristics. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2009;19:1160-1165.

42. Hoskins W.J., Bundy B.N., Thigpen J.T., et al. The influence of cytoreductive surgery on recurrence-free interval and survival in small-volume stage III epithelial ovarian cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 1992;47:159-166.

43. Buy J.N., Ghossain M.A., Sciot C., et al. Epithelial tumors of the ovary: CT findings and correlation with US. Radiology. 1991;178:811-818.

44. Meyers M.A., Oliphant M., Berne A.S., et al. The peritoneal ligaments and mesenteries: pathways of intra-abdominal spread of disease. Radiology. 1987;163:593-604.

45. Feldman G.B., Knapp R.C. Lymphatic drainage of the peritoneal cavity and its significance in ovarian cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1974;119:991-994.

46. Coakley F.V., Hricak H. Imaging of peritoneal and mesenteric disease: key concepts for the clinical radiologist. Clin Radiol. 1999;54:563-574.

47. Meyers M.A. Intraperitoneal spread of malignancy—pathways of ascitic flow. In: Meyers M.A., editor. Dynamic Radiology of the Abdomen. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2000:131-225.

48. Dvoretsky P.M., Richards K.A., Angel C., et al. Distribution of disease at autopsy in 100 women with ovarian cancer. Hum Pathol. 1988;19:57-63.

49. Dauplat J., Hacker N.F., Nieberg R.K., et al. Distant metastases in epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Cancer. 1987;60:1561-1566.

50. Di Re F., Fontanelli R., Raspagliesi F., et al. Pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy in cancer of the ovary. Baillieres Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 1989;3:131-142.

51. Coakley F.V. Staging ovarian cancer: role of imaging. Radiol Clin North Am. 2002;40:609-636.

52. Friedlander M.L. Prognostic factors in ovarian cancer. Semin Oncol. 1998;25:305-314.

53. Jemal A., Siegel R., Ward E., et al. Cancer statistics, 2007. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:43-66.

54. Current. FIGO staging for cancer of the vagina, fallopian tube, ovary, and gestational trophoblastic neoplasia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009;105:3-4.

55. Marsden D.E., Friedlander M., Hacker N.F. Current management of epithelial ovarian carcinoma: a review. Semin Surg Oncol. 2000;19:11-19.

56. Young R.C., Decker D.G., Wharton J.T., et al. Staging laparotomy in early ovarian cancer. JAMA. 1983;250:3072-3076.

57. Leblanc E., Querleu D., Narducci F., et al. Surgical staging of early invasive epithelial ovarian tumors. Semin Surg Oncol. 2000;19:36-41.

58. Forstner R., Hricak H., Occhipinti K.A., et al. Ovarian cancer: staging with CT and MR imaging. Radiology. 1995;197:619-626.

59. Coakley F.V., Choi P.H., Gougoutas C.A., et al. Peritoneal metastases: detection with spiral CT in patients with ovarian cancer. Radiology. 2002;223:495-499.

60. Pannu H.K., Bristow R.E., Montz F.J., et al. Multidetector CT of peritoneal carcinomatosis from ovarian cancer. Radiographics. 2003;23:687-701.

61. Walkey M.M., Friedman A.C., Sohotra P., et al. CT manifestations of peritoneal carcinomatosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1988;150:1035-1041.

62. Tempany C.M., Zou K.H., Silverman S.G., et al. Staging of advanced ovarian cancer: comparison of imaging modalities—report from the Radiological Diagnostic Oncology Group. Radiology. 2000;215:761-767.

63. Steinberg J.J., Demopoulos R.I., Bigelow B. The evaluation of the omentum in ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 1986;24:327-330.

64. Carnino F., Fuda G., Ciccone G., et al. Significance of lymph node sampling in epithelial carcinoma of the ovary. Gynecol Oncol. 1997;65:467-472.

65. Sakai K., Kamura T., Hirakawa T., et al. Relationship between pelvic lymph node involvement and other disease sites in patients with ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 1997;65:164-168.

66. Ronnett B.M., Zahn C.M., Kurman R.J., et al. Disseminated peritoneal adenomucinosis and peritoneal mucinous carcinomatosis. A clinicopathologic analysis of 109 cases with emphasis on distinguishing pathologic features, site of origin, prognosis, and relationship to “pseudomyxoma peritonei.”. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:1390-1408.

67. Brown D.L. A practical approach to the ultrasound characterization of adnexal masses. Ultrasound Q. 2007;23:87-105.

68. Brown D.L., Doubilet P.M., Miller F.H., et al. Benign and malignant ovarian masses: selection of the most discriminating gray-scale and Doppler sonographic features. Radiology. 1998;208:103-110.

69. Jeong Y.Y., Outwater E.K., Kang H.K. Imaging evaluation of ovarian masses. Radiographics. 2000;20:1445-1470.

70. Mansour G.M., El-Lamie I.K., El-Sayed H.M., et al. Adnexal mass vascularity assessed by 3-dimensional power Doppler: does it add to the risk of malignancy index in prediction of ovarian malignancy? four hundred-case study. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2009;19:867-872.

71. Mironov S., Akin O., Pandit-Taskar N., et al. Ovarian cancer. Radiol Clin North Am. 2007;45:149-166.

72. Leen E. Ultrasound contrast harmonic imaging of abdominal organs. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2001;22:11-24.

73. Jokubkiene L., Sladkevicius P., Valentin L. Does three-dimensional power Doppler ultrasound help in discrimination between benign and malignant ovarian masses? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;29:215-225.

74. Buy J.N., Ghossain M.A., Hugol D., et al. Characterization of adnexal masses: combination of color Doppler and conventional sonography compared with spectral Doppler analysis alone and conventional sonography alone. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;166:385-393.

75. Khan O., Cosgrove D.O., Fried A.M., et al. Ovarian carcinoma follow-up: US versus laparotomy. Radiology. 1986;159:111-113.

76. Johnson R.J. Radiology in the management of ovarian cancer. Clin Radiol. 1993;48:75-82.

77. Sohaid S., Reznek R., Husband J. Ovarian cancer. In: Husband J.E.S., Reznek R.H. Imaging in Oncology. 1st ed. Oxford: Isis Medical Media Ltd; 1998:277-308.

78. Tsili A.C., Tsampoulas C., Charisiadi A., et al. Adnexal masses: accuracy of detection and differentiation with multidetector computed tomography. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;110:22-31.

79. Amendola M.A. The role of CT in the evaluation of ovarian malignancy. Crit Rev Diagn Imaging. 1985;24:329-368.

80. Ferrandina G., Sallustio G., Fagotti A., et al. Role of CT scan-based and clinical evaluation in the preoperative prediction of optimal cytoreduction in advanced ovarian cancer: a prospective trial. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:1066-1073.

81. Sanders R.C., McNeil B.J., Finberg H.J., et al. A prospective study of computed tomography and ultrasound in the detection and staging of pelvic masses. Radiology. 1983;146:439-442.

82. Shiels R.A., Peel K.R., MacDonald H.N., et al. A prospective trial of computed tomography in the staging of ovarian malignancy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1985;92:407-412.

83. Kurtz A.B., Tsimikas J.V., Tempany C.M., et al. Diagnosis and staging of ovarian cancer: comparative values of Doppler and conventional US, CT, and MR imaging correlated with surgery and histopathologic analysis—report of the Radiology Diagnostic Oncology Group. Radiology. 1999;212:19-27.

84. Rieber A., Nussle K., Stohr I., et al. Preoperative diagnosis of ovarian tumors with MR imaging: comparison with transvaginal sonography, positron emission tomography, and histologic findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;177:123-129.

85. Hricak H., Chen M., Coakley F.V., et al. Complex adnexal masses: detection and characterization with MR imaging—multivariate analysis. Radiology. 2000;214:39-46.

86. Romer W., Avril N., Dose J., et al. Metabolic characterization of ovarian tumors with positron-emission tomography and F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose [in German]. Rofo. 1997;166:62-68.