Chapter 39 Ovarian Cancer

Staging

Staging

The standard staging system for ovarian cancer is presented in Table 39-1. Ovarian cancer is surgically staged according to the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging system.

TABLE 39-1 INTERNATIONAL FEDERATION OF GYNECOLOGY AND OBSTETRICS (FIGO) STAGING FOR PRIMARY CARCINOMA OF THE OVARY

| Stage I | Growth limited to the ovaries |

| Stage Ia | Growth limited to one ovary; no ascites. No tumor on the external surface; capsule intact |

| Stage Ib | Growth limited to both ovaries; no ascites. No tumor on the external surfaces; capsules intact |

| Stage Ic | Tumor either stage Ia or Ib but with tumor on the surface of one or both ovaries or with capsule ruptured or with ascites present containing malignant cells or with positive peritoneal washings |

| Stage II | Growth involving one or both ovaries with pelvic extension |

| Stage IIa | Extension or metastases, or both, to the uterus or tubes, or both |

| Stage IIb | Extension to other pelvic tissues |

| Stage IIc | Tumor either stage IIa or IIb but with tumor on the surface of one or both ovaries or with capsule or capsules ruptured or with ascites present containing malignant cells or with positive peritoneal washings |

| Stage III | Tumor involving one or both ovaries with peritoneal implants outside the pelvis or positive retroperitoneal or inguinal nodes, or both. Superficial liver metastasis equals stage III. Tumor is limited to the true pelvis, but with histologically proven malignant extension to small bowel or omentum |

| Stage IIIa | Tumor grossly limited to the true pelvis with negative nodes but with histologically confirmed microscopic seeding of abdominal peritoneal surfaces |

| Stage IIIb | Tumor of one or both ovaries with histologically confirmed implants of abdominal peritoneal surfaces, none exceeding 2 cm in diameter. Nodes negative for disease |

| Stage IIIc | Abdominal implants >2 cm in diameter or positive retroperitoneal or inguinal nodes, or both |

| Stage IV | Growth involving one or both ovaries with distant metastasis. If pleural effusion is present, there must be positive cytologic test results to allot a case to stage IV. Parenchymal liver metastasis equals stage IV. |

Even though all microscopic disease may appear to be confined to the ovaries at the time of laparotomy, microscopic spread may have already occurred; thus, patients must undergo a thorough surgical staging. Procedures necessary to stage ovarian cancer are shown in Box 39-1.

Classification

Classification

The histologic classification of ovarian neoplasms is listed in Table 39-2. These lesions fall into four categories according to their tissue of origin. Most ovarian neoplasms (80% to 85%) are derived from coelomic epithelium and are called epithelial carcinomas. Less common tumors are derived from primitive germ cells, specialized gonadal stroma, or nonspecific mesenchyme. In addition, the ovary can be the site of metastatic carcinomas, most often from the gastrointestinal tract or the breast.

TABLE 39-2 HISTOGENETIC CLASSIFICATION OF PRIMARY OVARIAN NEOPLASMS

| Derivation | Type of Tumor |

|---|---|

| Coelomic epithelial origin (80%-85%) |

∗ Combined germ cell and specialized gonadal-stromal elements.

Data from Hart WR, Morrow CP: The ovaries. In Romney SL, Gray MJ, Little AO, et al (eds): Gynecology and Obstetrics: The Health Care of Women, 2nd ed. New York, McGraw-Hill, 1981.

Epithelial Ovarian Carcinomas

Epithelial Ovarian Carcinomas

PATHOLOGIC FEATURES

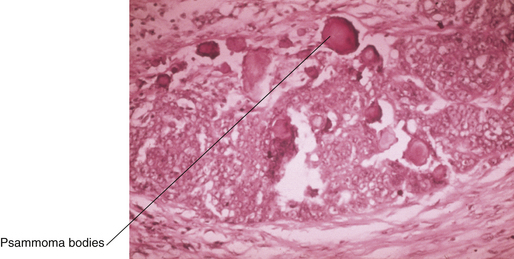

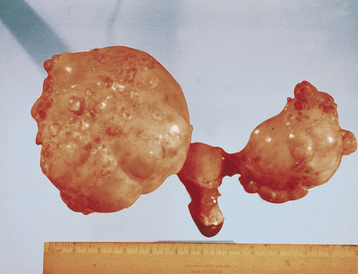

Serous tumors resemble fallopian tube epithelium histologically (Figure 39-1). About 30% of patients with stage I and stage IIa disease have bilateral involvement. On gross examination, serous carcinomas have an irregular and multilocular appearance (Figure 39-2).

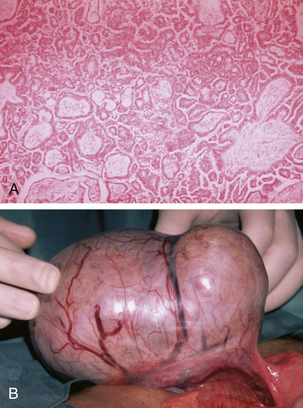

Tumors of low malignant potential or borderline histologic appearance exist for each histologic type. About 5% to 10% of malignant serous tumors are borderline (Figure 39-3), whereas 20% of malignant mucinous tumors fall into this category. The endometrioid, clear cell, and Brenner tumors are only rarely borderline.

MANAGEMENT OF EPITHELIAL OVARIAN CANCER

Early-Stage Disease

Definitive diagnosis requires an intraoperative frozen section. In patients with no gross evidence of disease beyond the ovary, the standard operation is total abdominal hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, infracolic omentectomy, and thorough surgical staging, as shown in Box 39-1. Patients who wish to preserve fertility may have a unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. In patients with grade 1 or 2 tumors confined to one or both ovaries after surgical staging, no further treatment is necessary. Patients with poorly differentiated (grade 3) tumors are subsequently treated with systemic chemotherapy.

Advanced-Stage Disease

It is unclear whether patients with “metastatic” borderline tumors benefit from chemotherapy.

Second-Look Laparotomy

In patients who are clinically free of disease after completing a prescribed course of chemotherapy (usually about six cycles), a second-look laparotomy may be performed to determine whether the patient has had a complete response to chemotherapy. However, it is unclear whether the performance of a second-look laparotomy and the administration of further treatment ultimately prolong survival, so the surgery should be confined to research settings. If there is no macroscopic or microscopic evidence of disease at second-look laparotomy, essentially the same procedures as are carried out for surgical staging should be performed (see Box 39-1). If gross disease is present, an attempt should be made to resect persistent disease to facilitate a response to subsequent therapy.

Armstrong D.K., Bundy B., Wenzel L., et al. Intraperitoneal cisplatin and paclitaxel in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:34-43.

Berek J.S. Epithelial ovarian cancer. In: Berek J.S., Hacker N.F., editors. Practical Gynecologic Oncology. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004:443-509.

Bristow R.E., Tomacruz R.S., Armstrong D.K., et al. Survival effect of maximal cytoreductive surgery for advanced ovarian carcinoma during the platinum era: A meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1248-1259.

Haber D. Prophylactic oophorectomy to reduce the risk of ovarian and breast cancer in carriers of BRCA mutations. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1660-1661.

Ozols R.F., Bundy B.N., Greer B., et al. Phase III trial of carboplatin and paclitaxel versus cisplatin and paclitaxel in patients with optimally resected stage III ovarian cancer: A Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3194-3200.

Etiology and Epidemiology

Etiology and Epidemiology Screening for Ovarian Cancer

Screening for Ovarian Cancer Clinical Features

Clinical Features Preoperative Evaluation

Preoperative Evaluation Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis Mode of Spread

Mode of Spread

Germ Cell Tumors

Germ Cell Tumors Specialized Gonadal-Stromal Tumors

Specialized Gonadal-Stromal Tumors Metastatic Cancers

Metastatic Cancers Fallopian Tube Carcinoma

Fallopian Tube Carcinoma