Chapter contents

9.1 Qi and Blood balance 203

9.2 The Three Jiao 207

9.3 Eight Principle pulse diagnosis 212

9.4 Five Phase (Wu Xing) pulse diagnosis 214

9.5 Nine Continent pulse system 222

Chinese medicine is a diverse practice and this is apparent in the range of extant approaches used in assessing the radial arterial pulse. The subject of this book has focused on one of these approaches; the Cun Kou system. Although without a doubt one of the most regularly used and popular pulse diagnostic systems, it is by no means the only pulse assessment system used in clinical practice.

Similarly, the diversity of CM practice is also apparent in the clinical context where individual practitioners may utilise more than one system of pulse assessment. In this situation, the choice of pulse assessment used stems from two key factors:

• The style of CM practised by the individual practitioner

• The patient’s cause for treatment: some pulse assumption systems are best used in assessing clinical dysfunction and overt illness whereas others are suited to the assessment of specific types of illness or even for health management. As such, not every pulse assessment system is necessarily relevant to all aspects of CM practice.

For these reasons, this chapter outlines five other pulse assessment systems that are clinically relevant to CM practice. These also use the radial arterial pulse positions, Cun, Guan and Chi, and or aspects of parameter assessment as discussed in Chapter 6 and Chapter 7. The five pulse assessment systems discussed in this chapter include:

• Qi and Blood balance

• San Jiao (Three Heaters)

• Eight Principles (Ba Gang)

• Five Phase (Wu Xing)

• Nine Continent.

9.1. Qi and Blood balance

In the First Difficult Issue of the Nan Jing, the pulse is discussed as the interaction of the ‘constructive’ with the ‘protective’ or the tangible fluid form called Blood and interaction with the body’s Qi (Unschuld 1986: p. 66). Both Qi and Blood and the relative function and quality of these are inseparable from the understanding of pulse in CM. It is not surprising, then, that in addition to specific pulse qualities that assess the relative quality and interaction of Qi and Blood, there is also a distinct approach to assessing the relative balance of these substances as well. This is termed the Qi/Blood balance. Theory dictates that the overall pulse in the left wrist corresponds to Blood, while the right-hand pulse correspondingly relates to Qi (Box 9.1).

Box 9.1

Relative strength of left and right pulses

The system probably derives from both actual and theoretical claims associated with gender-related pulse differences. The Qi represents Yang and so within the theoretical construct of Yin and Yang the Qi side pulses should feel stronger on the right side for women to balance their inherently Yin nature. For men this is reversed. The Blood represents Yin, so the Blood side pulses should feel stronger in men to balance their inherently Yang nature.

Clinically, the theoretical construct in relation to gender-related differences between the left and right pulses does not appear to be supported. King et al (2006) found that differences do occur between left and right hand pulses, but these are not gender dependent, with the majority of individuals being stronger on the right-hand side or having pulses of equal strength on both sides. Further research into this area is required to substantiate the clinical relevance of this pulse assumption theory.

9.1.1. Relationship of the Qi and Blood to the Zang organs

Similar to the other systems of pulse diagnosis, the conceptual basis of assessing the Qi/Blood balance is based loosely on the Nan Jing arrangement of the Zang (Yin) organs at the Cun, Guan and Chi pulse positions on each side (Table 9.1). From this arrangement, the three zang associated with the left pulse positions relate to the strength of Blood and the three Zang associated with the right pulse positions relate to the strength of Qi.

| Left side pulses | Right side pulses | |

|---|---|---|

| Blood | Qi | |

| Heart (Moves Blood) | Cun | Lung (Da Qi/Zheng Qi/Air) |

| ↑ | ↑ | |

| Liver (Stores Blood) | Guan | Spleen (Gu Qi/food) |

| ↑ | ↑ | |

| Kidney (Kidney Yin-Blood matrix) | Chi | Pericardium (Kidney Yang-Motive force) |

| Prenatal Qi | Postnatal Qi | |

| Constitution | Digestion |

9.1.1.1. The right side pulse and the Zang organs

The relationship between the organs represented at the three pulse positions on the right side and Qi is as follows:

• The Cun position relates to the lungs and its function of deriving Da Qi from the air and storing Zheng Qi. The lungs are considered the ‘governor of Qi’ (Nei Jing).

• The Guan position relates to the Spleen and Stomach, which are responsible for deriving the nutritive or Gu Qi, with digestion playing an integral part of the Qi transformation process.

• At the Chi position the Triple Heater and Pericardium have theoretical connections to the Kidneys and are consequently viewed as an extension of Kidney Yang, the foundation of Qi in the body.

9.1.1.2. The left side pulse and the Zang organs

A similar relationship is noted for the associated Zang represented at the pulse sites on the left wrist.

• The Cun position is associated with the Heart which ‘rules the blood’, circulating it through the circulatory system.

• The Liver, which is associated with the Guan position, stores the Blood (and to some degree is responsible for the quality of the blood after production. For example, Liver heat produces Blood heat). It also plays a role in the distribution of Blood throughout the body, as needed via its role in enabling the smooth flow of Qi.

• At the Chi position are the Kidneys pulse, and in particular Kidney Yin, which stores the essence and has a relationship with the production and nutritive function of blood. Kaptchuk (2000) additionally recognises the role of the Kidneys to ‘store the essence, rule birth, development and maturation – the stuff of life and development’ (pp. 83-84). This represents the constitutional aspect of the individual.

Hence the left-hand pulse represents the Blood. The Blood pulse could be described as also representing the prenatal Qi. Consequently, the left side in Chinese medicine also has some relationship to the concept of ‘constitution’ proposed by the Shen system. The relationship is shown in Table 9.2.

| += “normal” strength; ++ = stronger than ‘normal’; −= weaker than ‘normal’; −− = very weak; ✓ = relatively stronger side. | ||

| Left side (Blood) | Right side (Qi) | Interpretation of findings |

|---|---|---|

| + (+1) | + + (+2) | This means Qi is stronger than Blood, which is of normal strength. This may signify hyperactivity of Qi or Qi stagnation |

| − (−1) | − − (−2) | This means that both Qi and Blood are weak, however, Qi is more deficient than Blood |

| + + (+2) | − (−1) | This means that Qi is weaker than normal, while Blood is stronger than would be expected. This could possibly mean Qi vacuity (deficiency) leading to Blood stasis (stagnation) |

| − − (−2) | − − (−2) | This signifies that both Qi and Blood are equally very deficient |

| + ✓ | + | This means that both sides are of “normal” strength, however the Blood side is slightly stronger. This can reflect simple variations in normal strength of Qi such as that associated with hunger or fatigue at the day’s end |

9.1.2. Applying the Qi/Blood pulse assumption system

This Qi/Blood pulse assumption system is founded on the precept of sufficient Qi to move the Blood volume and sufficient Blood to nourish the Qi. This symbiotic relationship ensures that there is good circulation of nutrients to all parts of the body, maintaining balance and good functioning.

This approach can be used in three ways:

• As a preventive health measure: When the individual, for all intents and purposes, is healthy; there are often no overt signs of illness. The approach is used to address any disharmony or imbalance of Qi or Blood before pathology presents, ideally addressing the imbalance to prevent disease.

• For assessing the Qi and Blood balance during illness: This is particularly relevant for conditions that are chronic in nature, especially when both Qi and Blood may be deficient, providing further diagnostic information to pinpoint the focus of treatment.

• For its prognostic value: If signs of distinct or absolute differences in strength are present, this system is also useful as a prognostic gauge of the severity of the illness. In this way, the greater the strength divergence between the left (Blood) and right (Qi) pulses, the more severe the illness. In this situation, the practitioner would be best served by using a more appropriate pulse assessment approach, such as the parameters or overall pulse qualities.

The process for evaluating the pulse in this system entails four stages:

Step 1 Assess the overall pulse strength within each side’s pulse

Assessment of the Qi/Blood balance primarily focuses on the parameter of strength, similar to assessment of the force of overall pulse qualities described in Chapter 7. Separately on each side, all three radial pulse positions are palpated simultaneously at each of the three levels of depth. For example, at the superficial level an ‘assessment’ is made by the practitioner as to the overall strength of the pulse palpating the Cun, Guan and Chi positions simultaneously. This procedure is repeated at the middle and deep levels of depth. The strength at all three levels of depth is then averaged to arrive at the overall strength for that side’s pulse. The procedure is repeated for the other side’s pulse.

Step 2 Assess the relative strength of the overall pulse between the two sides

Once a baseline ‘measure’ for each side’s overall pulse strength is obtained, the system, as with all comparative applications of pulse assessment, requires the strength between the two sides to be compared (that is, the relative difference in pulse strength between the sides). In this way, irrespective of whether both left and right side pulses are overall weak or overall strong, one side is compared to the other side to determine which of the two is relatively stronger or weaker. For example, both the left and right pulses may equally be assessed as ‘weak’ – lacking in strength -, yet of the two sides, the left pulse may be weaker than the right. Thus the right pulse is assessed as been relatively stronger, but need not be a definitively ‘strong’ pulse. It is only relatively stronger because the left pulse is weaker.

During the assessment the practitioner should try and maintain a similar amount of finger strength when palpating the left and right sides. To confirm that this is the case, always ask for feedback from the patient about whether the strength being applied is perceived by them as being similar.

Step 3 Assess whether any relative strength differences are due to vacuity (deficiency) or repletion (excess)

This step involves the subsequent evaluation of any perceived relative strength differences found in Step 2. This includes evaluating the pulse strength in both relative and absolute terms, to determine the presence of vacuity or replete patterns.

Relative strength differences

For health of the circulatory system Qi and Blood must be relatively balanced. Relative differences in pulse strength between the two sides indicate that the Qi and Blood are unbalanced. (This is in spite of whether both pulses are overall/absolute weak (that is forceless), of normal strength or have an increase in strength (forceful).)

Differences in relative strength imply that while the individual may be ‘healthy’ the identified imbalance represents a potentially impending imbalance/illness if not addressed. Accordingly, treatment attempts to address the rebalancing of the body’s Qi and Blood.

Absolute strength differences

If there is a significantly noticeable difference in pulse strength between the two sides a judgement needs to be made by the practitioner about whether:

• One side is weaker and the other is of ‘normal’ strength, or

• One side is stronger and the other is of ‘normal’ strength.

Thus the practitioner is also required to determine the ‘absolute’ strength within each side’s pulse: that is, is the pulse forceful or is it forceless? This is required to determine whether the ‘weaker’ pulse is reflecting a ‘vacuity/deficiency’ or whether it is of ‘normal’ strength but feels weaker because the other side’s pulse is stronger than usual. Thus:

• An increase in pulse strength above ‘normal’ in the left or right pulse indicates replete disturbance of the Qi or Blood, depending on which side the pulse was stronger

• A decrease in pulse strength below ‘normal’ in the left or right pulse indicates vacuity of the Qi or Blood, depending on which side the pulse was weaker.

In either situation, the Qi/Blood balance is viewed as imbalanced and pathology already manifested. (Interpretation of the pulse via another pulse assumption system is preferred in this situation, as more appropriate and clinically useful information for informing about the nature of the pathology can be gained. For example, examining the pulse using pulse parameters and overall pulse qualities.)

If the left and right pulses are similar in strength then the Qi and Blood are balanced, irrespective of both being stronger or weaker in strength than is normal for that patient. As such, other pulse assumption systems such as overall pulse qualities or the Five Phase approach may be of more value in interpreting the pulse wave for diagnostic purposes and informing treatment.

Other pulse parameters in the determination of Qi/Blood balance

Additionally, the pulse parameters of arterial wall tension and ease of pulse occlusion can be utilised to provide further information about the quality of Qi and Blood:

• An increase in arterial tension in the left pulse indicates Blood vacuity.

• A decrease in arterial tension in the right pulse indicates Qi vacuity.

• A pulse which is easy to occlude indicates Qi and Blood vacuity irrespective of which side it is located on.

Step 4 Select appropriate acupuncture points, herbs or other therapeutic interventions to address the findings

Once it has been determined whether there are any differences in strength between the left and right pulses, relative or absolute, and if the differences are due to vacuity or repletion of the Qi or Blood, the practitioner needs to select appropriate acupuncture points, herbs or other therapeutic interventions to address the disharmony. Acupuncture and herbs would either supplement or drain, depending on the nature of the identified disharmony. Additionally, the patient’s diet may need to be addressed.

9.1.4. Extraneous variables affecting the assessment of Qi/Blood balance

9.1.4.1. Practitioner handedness

The problem with comparing assessments of inter-arm differences, from the practitioner’s perspective, is the consistent application of finger pressure. A difference in finger strength being applied by the practitioner between left and right sides would cause the pulse sensations to be perceived differently and the results interpreted incorrectly. For example, if a practitioner is right-hand dominant, they would have better discrimination in adjusting their fingers on the right hand when feeling for the different levels of depth as compared to their left hand. This may cause a bias in the assessment of inter-arm differences in pulse strength.

Solution to the problem

Palpating both pulses simultaneously helps to limit and control any bias in finger strength discrimination introduced by being left- or right-hand dominant. Either as a beginner to the technique, or as a seasoned practitioner, receiving feedback from the patient concerning finger strength will provide valuable feedback for:

• Learning to discriminate strength/finger pressure between the two hands

• Continuing to ensure that strength/pressure discrimination is similar

• Limiting extraneous variables and subsequent interpretation within a diagnostic framework.

As such, simultaneous palpation ensures that:

• Finger palpation is being applied accurately

• The technique is being applied reliably

• Any findings are valid within the conceptual framework being used.

9.1.4.2. Subject handedness

Further concerns with the system relate to the dominant hand of the subject or patient being assessed. For example, the individual’s dominant hand usually has a greater muscle bulk, requiring a greater blood supply. Accordingly, the arteries will have remodelled to deliver the blood and nutrients required for healthy function. This may be felt as a wider artery. Thus assessment of the Qi/Blood balance maybe skewed in someone with a noticeable difference in arm use and muscle bulk. This may also apply to individuals with injuries such as sprains or broken bones in which the arm has been in a period of immobilisation. Thus pulse difference may be reflecting localised changes in blood flow requirements rather than being a systemic indicator of Qi or Blood balance.

Solution to the problem

Also look at other pulse parameters such as arterial tension. Often if Blood is deficient then arterial tension will be increased. When Qi is deficient then the arterial tension may be decreased.

9.2. The San Jiao: Three Heaters

The view that the individual’s physiology is a microcosmic reflection of the macrocosm, the world in which the individual resides, is a recurring theme in CM. The best-known application of this theme in pulse diagnosis is the Five Phases (Wu Xing), but another is the San Jiao pulse system. In particular, the San Jiaos is an application of the Heaven-Earth-Humanity theme. It relates specifically to the thoracic, abdominal and pelvic cavities of the torso; these are known as the Three Jiaos (See Box 9.2). Each cavity has an association with certain organs and their association with the distribution and metabolism of Qi and fluids.

Box 9.2

Translations of the term ‘Jiao’

The term ‘Jiao’ can be translated in two ways:

• The first translation relates to its common conceptualization as ‘burners’ or ‘heating’ action. In this context Jiao literally means charcoal. In many English CM texts, Jiao has been taken to mean that the three torso cavities are distinctly related to a warming or heating action.

• The second translation relates to the concept of water channels. This refers to the CM San Jiao concept of relating the Jiaos to fluid metabolism: as conduits for both the movement and transformation of fluids. Traditional descriptions of the form of the San Jiao often describe the organ as being composed of a network of channels for fluid distribution (Qu & Garvey 2001).

In this context, the Chinese cosmological perspective on the function and nature of Heaven, Earth and Human is reflected respectively within these three regions of the torso (Table 9.3):

• The Heart and Lungs are located in the thoracic cavity and are ascribed to Heaven and production of Qi (movement and function)

• The Spleen and Stomach are located in the abdominal cavity and are ascribed to the Earth and are responsible for the separation of the pure from the impure – (transportation and transformation – digestion) and Gu Qi, nutrients and fluids. The Liver also has a relationship with digestion.

• The pelvic cavity contains the Kidneys and Intestines. These are ascribed to Humanity, and besides excretion (liquid and solid waste), are considered to be the foundation of Yin and Yang in the body.

| Left Position | Right Position | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cun | Heart | Upper Jiao | Lung |

| Guan | Liver | Middle Jiao | Spleen |

| Chi | Kidney Yin | Lower Jiao | Kidney Yang |

9.2.1. San Jiao organ

The San Jiao or Triple Heater (Triple Energiser) organ is a concept unique to CM. Rather than being a distinct organ, it is a synergy of the three distinct regions, the three cavities which are often described as defining the San Jiao. Physiologically it is attributed to fluid metabolism, hence its definition as a curious Fu. In addition to the interaction with the fluid the San Jiao can be also classified as a curious Fu for the ‘storage’ of the organs Zang and Fu which are enclosed within the respective torso cavities. In this way, the San Jiao is described as both a Fu or hollow organ as well as a curious Fu; for both the cavity-like structure that it is and the interaction that it has in the metabolism and distribution of fluid, one of the three treasures (San Bao) and storage of the organs. Even in CM the conceptual ‘organ’ that is the San Jiao is unique (Box 9.3).

Box 9.3

The application of the San Jiao in CM

This system has a number of different variations and names within the literature, but is primarily assessing the functional integrity of the San Jiao (Triple Heater) via the organs located within each of the respective cavities or Jiaos of the torso.

9.2.2. Association of the pulse to the San Jiao

The logic of this pulse system lies with the location of the organs within the three cavities or Jiao in the torso. In this way, if a Jiao becomes dysfunctional then everything that it encloses or stores would additionally be affected, including the organs: and this is reflected in the related organ’s pulse at the radial arterial.

In using this San Jiao pulse system, the corresponding pulse positions on each wrist are paired and associated with a Jiao (Table 9.3). These are:

• Upper Jiao: Paired Cun pulse positions

• Middle Jiao: Paired Guan pulse positions

• Lower Jiao: Paired Chi pulse positions.

Therefore, in this context, the zangfu organ pulses reflect the functional capacity of the related Jiao in which the organs reside. However, Jiao related dysfunction presents with simultaneous changes in two of the pulse positions; the two pulse positions relate to the two organs which the Jiao encloses (Table 9.4).

| Combined pulse positions/sites | Related cavity | Organs within cavity | Division | Organ function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cun | Thoracic cavity | Heart and Lungs | Heaven: Yang/intangible/function | Ruler of Blood-Visible movement of blood and Master of Qi-breathing |

| Guan | Abdominal cavity | Spleen and Stomach, Liver | Earth: Yin/solid | Transformation and transportation-(ripen and rot). Smooth flow of Qi |

| Chi | Pelvic cavity | Kidneys and intestines | Humanity: interaction of Yin and Yang-water/liquid | Excretion-Yin and Yang |

For example, if the heart is dysfunctional then resultant changes in pulse rhythm or strength may occur, or alternatively, the Heart pulse at the left Cun position may present with a decrease in strength. Similarly, if the patient presents with shortness of breath then the Lung would be indicated and the pulse at the right Cun position would reflect this. In both these situations, the individual organ is dysfunctional, not the Jiao because only a single pulse position was affected; the pulse that related to that specific organ. However, in the situation where the individual presents with both Lung and Heart symptoms described, this could be described as an Upper Jiao dysfunction or illness. In this sense, it is the poor functioning of the Upper Jiao distribution of fluids and nutrients that has caused the associated organs, (the heart and lungs), in this cavity to become dysfunctional. In terms of pulse diagnosis, this should be reflected bilaterally in the wrist pulses relating to the Upper Jiao. In the case just described, then there should be a similar pulse quality or change in pulse parameter manifesting simultaneously at the left and right side Cun positions: the organ dysfunction inferred from the pulse is secondary to the related Jiao dysfunction. In a clinical context, rather than directing treatment at the Lung or Heart separately, treatment is directed towards the Upper Jiao instead: the cavity in which the Lungs and Heart are housed (Box 9.4). Conversely, if a pathological pulse quality is presenting in only one of the paired pulse positions, then that respective organ is considered to be dysfunctional rather than the Upper Jiao and, as such, treatment focuses on that particular organ (Box 9.5).

Box 9.4

Three Jiaos and the Cou Li

In their discourse on the classical medical location, shape and structure of the San Jiao, Qu & Garvey (2001) proposed that rather than the distinct organ entities, it is the lining or distribution network of actual cavities/spaces between tissue linings that constitutes the San Jiao. These are termed the Cou Li. Cou refers to cavities. The largest of these are the thoracic (chest), abdominal and pelvic cavities. Additionally, the San Jiao Cou concept also encompasses smaller spaces in the extremities and muscles. All these spaces are connected via a distributing network of tubes. These are termed the Li. Based on classical descriptions of the San Jiao in the Ling Shu (Chapter 18), they propose that the San Jiao is constituted from the cavities rather than actual organs. The San Jiao is described by Kaptchuk (2000: p. 96) as having ‘a name but no shape’, attributed to its ‘formless’ nature.

Some interesting recent published research papers indirectly supports the Qu & Garvey discourse. Lee et al (2004), Shin et al (2005) and Lee et al (2005) report on the histological identification of threadlike structures on the surfaces of internal organs, in the blood and lymphatic vessels, and under the skin. These are termed the Bonghan ducts after Bonghan Kim who reported first observing them in 1963. Lee et al (2004) describes the Bonghan ducts as a ‘circulatory system that was completely different from the blood vascular, nervous and lymphatic systems’ (p. 27). As a circulatory system, it is reported a distinct and observable liquid flow within these vessels with a hypothesized large mitochondrial count and nerve-like properties (p. 6, Lee et al, 2005).

Just as the San Jiao is a radical concept to a physiologist, Shin et al (2005) describe the Bonghan ducts similarly as a radical challenge to modern anatomy. Lee et al (2005) state:

Whatever the eventual outcome of deeper investigations of these claims, the finding of the novel structure inside lymphatic vessels is not mere curiosity but rather a herald of a breakthrough in establishing the third circulatory system that consists of the Bonghan ducts inside blood vessels, on the organ surfaces and under the skin. Further studies of its histological aspects and physiological functions suggest the possibility of new insights in both biology and medicine as well as acupuncture theory (p. 6).

While speculative (as is much of the discussion on the San Jiao), if these structures are as reported, it is not inconceivable that they occur throughout the lining of the cavities and interstitial spaces of the muscles, as explained in the concept of the Cou Li or San Jiao. Further investigations are required to establish certain claims about the ducts reported by Kim (1965) ‘the lymphatic intravascular threadlike structures … related to immunological and hematopoietic function’ (Kim 1965, as reported in Lee et al, 2005).

It is the immunologic claim that is of most interest to the concept of the San Jiao as the distributions of Cou via the Li within the muscle and skin also have an immunologic function against external pathogens (Qu & Garvey, 2001).

Box 9.5

Relation of the San Jiao to anatomical and physiological structures

The literature relates the San Jiao to a range of anatomical and physiological structures, including:

• Cou Li

– Organs

– Cavities

– Water channels

• Burners

– Heat and metabolism.

9.2.3. Application and assessment

This system of pulse diagnosis uses the Zang organ arrangement in the Nan Jing to imply the functional integrity of the related cavity, or Jiao in which the organs reside (see Box 9.4 for a discussion of Cou Li).

San Jiao pulse diagnosis makes use of the paired pulse positions of each arm. For example, left Cun is matched with right Cun (upper Jiao), right Guan with left Guan (middle Jiao) and right Chi with left Chi (lower Jiao). Both positions are palpated simultaneously; the practitioner’s right index finger is placed on the left Cun and the left index finger on the right Cun. The paired pulse positions are palpated simultaneously to identify possible common changes in pulse parameters (excluding pulse rate, which should be consistent across all positions) or the CM pulse quality that is manifesting within each arm’s pulse (Box 9.5).

Although pulse assessment in the San Jiao pulse system focuses primarily on the parameter of pulse force, other changes in additional pulse parameters – for example, pulse occlusion or depth – may also be utilised, as long as they occur in both corresponding pulse positions in the Jiao in question. But for purposes of demonstrating the system we focus here on the parameter of force and the related assessment of relative strength.

There are five stages to the assessment process for interpreting pulse findings in the San Jiao pulse assumption system:

Step 1 Assess the overall pulse strength at each pair of pulse positions

Starting at the Cun positions, the overall strength is assessed at the paired pulse positions respectively on each arm. (Paired pulse positions refer to the left and right Cun, left and right Guan and left and right Chi, hence three paired pulse positions.) Assessment focuses on the parameter of strength. An assessment of strength at each of the three levels of depth, (superficial, middle and deep), is taken and then averaged to arrive at the overall strength for the respective pulse position on the left and right side of each pulse pairing.

Alternatively, assessment of strength can be undertaken at the middle level of depth only, for the respective pulse position on the left and right side of each pulse pairing. (There is little information in the literature regarding which approach to use)

Step 2 Assess the relative strength of the overall pulse between the left and right sides for each pair of position

Once an assessment of the pulse strength is obtained for each side of the paired pulse positions, it must be determined whether the pulse information is suitable for interpretation in the San Jiao approach. The logic of use for this pulse assumption system is based on the premise that when a Jiao is dysfunctional then both organs within the Jiao, and their related pulses, are similarly affected.

Once it is established that each of the three pairs of pulse positions (that is, within each Jiao) has a similar strength, the three Jiaos must be compared. The paired pulse positions are compared to determine whether there is a similar strength occurring between the three paired positions or not; remembering that each pair of positions reflect the functioning of the related Jiao. Thus the paired Cun positions reflect the Upper Jiao and consequently the functioning of that Jiao is inferred from the strength of the combined Cun positions. In this way, the functional integrity of each Jiao is compared against the function of the other Jiao. This comparison assessment assesses both relative differences in strength as well as absolute differences in strength, as described below.

Transitory changes in strength

Transitory differences in strength may indicate normal circadian rhythms of the body. For example, relatively stronger Guan positions may reflect the fact that the patient has just eaten, thus the Blood is in the digestive tract. Relatively weaker Chi positions pulse may occur at the end of the day. However, if such differences are not associated with any circadian cycles then this may indicate an actual or established underfunctioning (rather than dysfunction) of that particular Jiao.

Established differences in strength

Established differences in strength are likely to occur when there are actual physiological problems or dysfunction in the related Jiao. Established differences refer to paired pulse positions that are classified either as ‘weak’, a pulse lacking strength, or ‘strong’, a pulse with strength greater than normal and for which transitory variables affecting strength have been excluded.

In the diagnostic interpretation, any region that is comparatively stronger than the other two regions indicates an excess or fullness. For example, the paired Cun positions are stronger than usual or as expected would indicate a condition affecting the upper Heater or the Cou Li. As the Cou Li are affected, so the organs in the region will be affected. Conversely, any region with less force than usual indicates a region of vacuity or deficiency. For either occurrence, treatment should address the Jiao rather than the individual organs affected.

Step 4 Determine whether any differences are relative strength differences or are distinct differences in force

The practitioner attempts to determine the overall relative strength of each of the Jiaos. If there are relative differences in strength between Jiaos, then we need to determine whether these differences are due to pulse strength that is stronger than usual or weaker than usual. This is done in assessing the force of cardiac contraction with other related factors, as described under the parameter of pulse force in section 7.6.

Step 5 Selecting an appropriate treatment intervention

Once it has been determined whether any strength differences between positions are relative strength related or absolute force differences, the practitioner next needs to select appropriate acupuncture points, herbs or other therapeutic interventions, including dietary and activity advice, to best address the findings.

9.2.4. Interpreting the San Jiao pulse assessment information

There are two presentations of the paired pulse positions when dysfunction is present:

• Strong paired positions: Reflecting replete (excess/fullness), stasis or obstructive conditions

• Weak paired positions: Reflecting vacuity (deficiency/empty) conditions

9.2.4.1. Strong paired positions

There are two possible indications for increased pulse force in a particular Jiao:

• Replete or excess conditions: For example, acute respiratory infection may cause a stronger Upper Jiao pulse.

• Stasis or obstruction: Stagnation in the Middle Jiao or food stagnation may result in a forceful Middle Jiao pulse, due to the accumulation of undigested food. Alternatively, the paired Chi positions may present as strong with constipation due to the retention of waste products, impairing free flow of Qi. Damp heat in the Lower Jiao will similarly present with both paired Chi positions as being stronger, accompanied possibly by signs and symptoms such as thrush or cystitis.

9.2.4.2. Weak paired positions

Weakness in a particular Jiao may be due to:

• Vacuity patterns: Vacuity of the Middle Jiao pulses may indicate impaired production of Qi, blood and fluids and the subsequent distribution of these substances to the other Jiaos. Alternatively, the paired Chi positions may present as weak in the presence of diarrhea or vacuous Kidney Qi. Weakness in the paired Cun positions can denote a respiratory and/or circulatory dysfunctions.

• Stagnation: Stagnation in the Middle Jiao or food stagnation may result in the Upper and Lower Jiao both having relatively weaker pulses, as the Middle Jiao is not distributing Qi between the three regions.

9.3. Eight Principle pulse diagnosis

The Eight Principles system is based on the broad classification of signs and symptoms associated with illness into eight categories to arrive at an overall picture of the nature of an illness and how the body is responding, thus informing the treatment approach. The eight categories include heat, cold, excess, deficiency, external, internal, Yin and Yang.

The system is not meant to apply a precise name to a condition or disease but rather to provide an explanatory diagnosis with regard to the affect and response the body is going through. Accordingly, it is a useful system for any difficult-to-diagnose conditions, especially where there may be multiple patterns occurring, providing meaningful information to focus the treatment approach. For example, if fever presents then the condition can be broadly categorised as hot, and heat-draining herbs and acupuncture points are used.

9.3.1. Using the Eight Principles to identify changes in pulse

The Eight Principles is a relatively simple approach to pulse diagnosis that can be of assistance in the overall diagnostic process, especially if you have difficulty identifying the pulse quality as it relates to the 27 specific CM pulse qualities.

As the experienced clinician realises, rarely does a pulse quality occur alone: it is usually in combination with at least one other quality or a combination of many parameters and this can make identification of overall pulse qualities difficult. In fact, often, there is no overall ‘traditional pulse quality’ to be felt, as described in the CM literature.

By using the Eight Principles pulse diagnosis you may be able to recognise a pattern emerging, with a combination of basic pulse parameters that defines one of the CM specific pulse qualities. As such, the Eight Principles may help with the pulse parameter system, identifying specific CM pulse qualities by simplifying recognition of the pulse changes.

The Eight Principles approach uses three general pulse parameters. These are:

• Pulse rate

• Level of depth

• Pulse force

Information obtained during pulse examination is categorised based on the relative changes occurring in these pulse parameters. For example, pulse rate can be increased or decreased from normal and thus is divided simply into Rapid or Slow. If the pulse is Rapid, then this is seen as a heat condition manifesting in the individual. Similarly, if the pulse is Slow then this indicates Cold. Both the level of depth and the pulse force similarly tell us something about the effect a condition is having on the body.

9.3.2. Using the pulse parameters within the Eight Principles concept

In the context of pulse diagnosis, the basic pulse parameters used in this system are the level of depth, pulse rate and strength. Each parameter as a standalone ‘diagnostic’ imparts only limited information about the condition. For example, an increase in pulse rate (perhaps the Rapid pulse) can be categorised as representing heat. However, whether the heat is due to an external pathogen or internal causes cannot be determined from this parameter alone (see Box 9.6). For this reason two other pulse parameters, pulse force and depth, are used in addition to rate (Table 9.6). It is the use of all three sets of parameters together that allows the practitioner to correctly identify the condition and inform treatment intervention within an Eight Principles context (Box 9.7). If a Rapid pulse also presents with a lack of force, it can therefore be categorised as vacuity heat (or empty heat, deficiency heat). If the Rapid pulse presented with excessive force then it can be categorised as Excess heat.

Box 9.6

Exceptions to the rule

The appearance of a superficial and forceful pulse at the start of an acute EPA is generally a sign of strong immune system, with Zheng Qi and blood rushing to the surface to fight off the pathogenic factor. However, the pulse may not be felt either strongest at the superficial level or forcefully in acute conditions if the individual is already Qi or Yang deficient. In the case of Yang deficiency, the pulse may be felt relatively strongest at the deep level, due to a lack of Yang Qi to raise it to the surface.

| Pulse parameters and appropriate Eight Principles category | Diagnosis | Mechanism | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate (Hot/Cold) | Depth (External/internal) | Force (Replete/vacuous) | ||

| Increased | Heat/Fire | Increase in quantity or functioning of Yang Qi | ||

| Increased | Superficial | External Heat | ||

| Increased | Superficial | Forceful | EPA Heat | Wei Qi meeting EPA-hence pulse rises to following the outflow of Qi to defence |

| Increased | Superficial | Weak | Vacuity of Yin | Yin can no longer anchor yang hence Yang floats or reverts to its nature of expanding and upward |

| Increased | Deep | Internal Heat | ||

| Increased | Deep | Forceful | Internal Replete Heat | Wei Qi meeting EPA-hence pulse descends to follow the inflow to defend the internal organs, or obstruction internally causes heat because of the stasis-obstruction |

| Increased | Deep | Forceless | Internal Vacuity Heat | Likely arising from some form of obstructive disorder with an underlying vacuity |

| Decreased | Cold | |||

| Decreased | Superficial | External Cold | ||

| Decreased | Superficial | Forceful | EPA Cold | Wei Qi meeting EPA-hence pulse rises to following the outflow of Qi to defend the body |

| Decreased | Superficial | Forceless | Vacuity of Yang | Not a likely combination. If occurs, more likely to reflect blood vacuity |

| Decreased | Deep | Internal Cold | ||

| Decreased | Deep | Forceful | Internal Replete Cold | Wei Qi meeting EPA-hence pulse descends to following the inflow of to defend the internal organs. EPA cold can ove directly to the internal in ST, LI, uterus |

| Decreased | Deep | Forceless | Internal Vacuity Cold | Yang is vacuous and hence no longer expand the pulse against the contracting nature of Yin, hence a deep pulse. With Cold the arterial tension will increase because Cold causes pain but also due to the nature of Cold to contract. That is, the smooth muscle contracts |

Box 9.7

The parameters in an Eight Principles context

Depth

• Depth indicates the location of the condition. Is it occurring at the exterior level of the body, for example if the body is fighting off an illness? Or is the illness due to internal factors or has it progressed into a deeper level within the body (interior)?

• Alternatively, a pulse felt relatively strongest at the superficial level may indicate that Yin is weak (and therefore cannot be felt at the deep level where it is usually represented), while a pulse that cannot be felt at the superficial level may be seen as vacuous Yang (insufficient Yang to lift it to the surface)

Rate

• The rate parameter reflects the response effect on cellular function and reveals the nature of the condition – is it heating? (increase in pulse rate) or is it cooling? (decrease in pulse rate).

Force

• The force indicates the chronicity of the process occurring, whether it is arising from an excess condition or from a vacuous condition.

To determine the nature or source of Excess (replete/full) heat, further differentiation of the pulse would be required. Where is the pulsation felt most forcefully, at the superficial or deep level of depth? If superficial, this would then appear to indicate an EPA of Heat. If the pulse is strongest at the deep level then the heat could be seen as either arising internally, or an EPA has now progressed to the internal level. The acuteness or chronicity of the condition can help provide further clues as to which case it may be.

Thus the basic pulse parameters can inform about the location, nature and duration of the condition. Treatment then aims to support ailing organs or correct Qi and Blood for vacuities; excess or repletion are drained, while EPAs are expelled (Box 9.7).

The Eight Principles system also encompasses a fourth category, Yin/Yang, which is used to describe the general nature of a condition. Whether a condition is described as Yin and Yang depends on the determination of the preceding three categories:

• Yin conditions are generally cold, vacuous (deficient) and internal and characterised by aversion to cold, tiredness, fluid retention, weak voice and dysfunction associated with organ related functions or with the Qi and Blood. Thus the pulse is likely to be slow, lack strength and be located at the deep level of depth.

• Yang conditions tend to be hot, replete (excess/full) and external and characterised by sudden appearance of symptoms or signs. Fevers, facial flushing, aversion to heat and a liking for cool drinks represent Yang type conditions. The pulse is likely to be rapid, forceful and be felt strongest at the superficial level of depth, in addition to the middle level of depth.

This categorisation approach using Eight Principles can also apply to chronic conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis that has a sudden acute flare-up, and hence Yang (heat) signs within a chronic Yin (Damp) condition. Similarly a Yin condition can have Yang signs. For example, vacuity of Yin may give rise to vacuity (empty/deficient) heat signs over time. Another common example is damp accumulation causing stagnation in the interior and eventually transforming to heat. This would be viewed as Yang signs within a Yin condition (in this case, accumulation of Yin fluids).

Thus the Eight Principles also can be used to identify:

• Vacuity heat/Yin vacuity conditions (heat conditions that arise from an inability of the body to slow or cool itself down – parasympathetic nervous system dysfunction), or

• Vacuity cold/Yang vacuity conditions (cold conditions that arise from an inability of the body to maintain metabolism or retain body warmth – sympathetic nervous system dysfunction).

9.3.3. Descriptive terminology must not be confused with the specific CM pulse quality names

Some literature sources use basic descriptive pulse qualities that relate to depth (Floating and Sinking), strength (Replete and Vacuous), and rate (Rapid and Slow) parameters, which can be used within the Eight Principles as demonstrated above. However, as distinct CM pulse qualities, there are other pulse parameters that define these CM pulse qualities beyond the Eight Principles system. (Refer to Chapter 6 and Chapter 7). For example the Floating pulse, while often described as strongest at the superficial level, is also defined by an incremental decrease in strength when finger pressure is applied. That is, the pulse can be felt at the superficial level but also at the middle level, to a lesser degree. As such, generic pulse parameter descriptors, as illustrated in Table 9.5, rather than specific CM pulse quality names, are best used in the Eight Principles system to prevent confusion with the overall CM pulse qualities.

| Eight Principles category | Pulse | Nature |

|---|---|---|

| Depth | Superficial | Location: External (li) |

| Deep | Internal (biao) | |

| Rate (nature) | Fast | Nature: Heat (re) |

| Slow | Cold (han) | |

| Force | Forceful | Chronicity: Replete (shi) |

| Forceless | Vacuity/deficiency (xu) | |

| Yin/Yang | A generalised overall description of the above three categories: hot, excess, external, etc. |

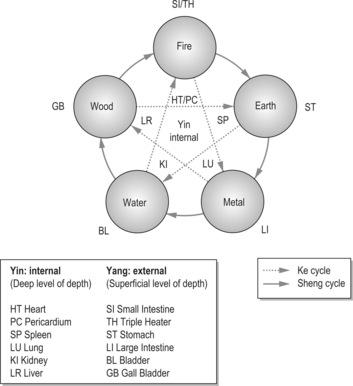

The Five Phases is a theoretical construct which arose from the writings of the Nei Jing and Nan Jing, organising natural phenomena in terms of Yin and Yang and recognising the cyclical relationships between them, for example seasonal changes reflected growth patterns in nature. Similar principles could also be applied to the human body, with organs assigned to each of the Five Phases, with each phase further differentiated into Yin and Yang.

Five Element acupuncture is a way of incorporating the system of correspondences or itemised lists of naturalistic phenomena attributed to each of the phases described in the Nei Jing (Chapter 4 and Chapter 5, Ni 1995). In this way, pathology or dysfunction can be categorised simply as the adverse interactions within and between the phases. The system and variations thereof are variably termed the ‘five stages of change’, ‘five elements’ (Rogers 2000), ‘five-agents doctrines’ (Unschuld 2003: p. 106) ‘five element constitutional acupuncture’ (Hicks et al 2004) or simply the Five Phases or movements.

In spite of the system’s purported European origins and popularisation by Worsley and others in the West, Birch (2007) notes the system as originally derived from Japan and the interpretive teachings of the Nan Jing by practitioner scholars during the 1920s and 1930s with the development of ‘Meridian Therapy’.

The system was ‘exported’ to Germany in the 1950s by a visiting German physician to Japan, whom returning to Germany was accompanied by Japanese teachers of the system. The following instructions on five phase pulse diagnosis stems primarily from the system as practiced in the ‘West’.

9.4.1. Five Phase and pulse assessment

The diagnostic use of pulse assessment in this pulse assumption system is predicated on the notion that disharmonies within the organ systems, whether emotionally, psychologically, physiologically or spiritually based, can be identified by certain changes occurring in the pulse. In this sense, disharmonies are caused by a disturbance affecting normal Qi function and consequently organ function.

Depending on the nature of the identified disharmony, acupuncture treatment aims to correct the identified disturbance through the movement, drainage or harmonisation of Qi between and within the organ groupings using the Sheng and Ke cycles (Box 9.8). A specific group of points termed Five Phase or elemental points located at the channel segments that transgress the distal portions of the limbs is needled for this purpose. There are additional point groupings that are also needled, including the Lou, Yuan, Mu and Back Shu points. This process of regulating Qi is termed the movement of energy and finds a use within Five Phase or elemental acupuncture.

Box 9.8

Sheng and Ke cycles

• Sheng cycle: Also termed the constructive or mother/son law, this cycle illustrates the relationship of organs and associated functions assigned to each element or phase support and assist with the functions of other organs. On a broader scale, it relates to the movement of the seasons. Hence Wood is associated with spring. Spring leads to summer, thus the Wood feeds Fire. The heat of summer turns to the humidity of long summer, associated with the Earth. Similarly, the human body (the microcosm) can be viewed as a reflection of the environment (the macrocosm) and so a similar relationship can be recognised in terms of organ function, with consecutive phases engendering the organ function of the next phase.

• Ke cycle: This is a controlling cycle, and represents the regulatory effect that certain organs have on others. It may also represent the adverse or pathological effect that an organ or phase would have on other organs and body functions if it became hyperactive or if the organ or phase it was regulating was under functioning. In this sense, particular organs or phases are normally considered capable of keeping other phases in check, but over-‘checking’ gives rise to illness.

9.4.2. Clinical use of Five Phasepulse diagnosis

In the Five Phase system, the pulse is used in two ways:

9.4.2.1. For health maintenance

By evaluating the subtle changes within the pulse, disturbance in any of the Five Phases or elements can be addressed. This is done through the assessment of differences in pulse strength within and between several pulse positions at the wrist. Strength differences in the pulse reflect the functional integrity of the organ, so if the organ function is compromised then the pulse would concomitantly be affected. In this sense, the pulse is used as a predictive sign of potential or impending illness. The system finds use as a construct for health maintenance, identifying potential organ and Qi imbalances via the pulse and correcting these with acupuncture before physical signs manifest (Box 9.9). According to Rogers (2000), the aim therefore is to ‘supply energy to those areas that are weak and to calm the energy of those areas that are over-active’ (p. 47).

Box 9.9

The importance of pulse diagnosis in Five Phase versus other CM systems

The use of pulse diagnosis in Five Phase acupuncture differs distinctly from other CM systems/models in that the pulse findings play a pivotal or even solitary role in the selection of acupuncture points for treatment. In other CM systems/models, pulse assessment contributes to informing diagnosis but does not necessarily dictate point or herb selection. Thus the pulse findings in the Five Phase pulse assumption system are used to determine whether acupuncture points are selected to drain excess Qi, supplement vacuities, or harmonise the function of elemental/phase organ Yin Yang partners.

The assessment of relative strengths derives from the Nan Jing’s view on the interconnectedness of the channels, and hence Qi, reflected in the pulse. Accordingly then, Birch (2007, prs. comm.) states ‘the core model of practice in the Nan Jing is to apply supplementation to the channels that are vacuous and drainage to the channels that are replete in order to restore yin-yang and five-phase balance’. This includes the distribution of Qi and its flow among the twelve channels. Assessment of the relative strength of the individual pulse positions are used to this end.

9.4.2.2. For identification of Qi imbalances

The second way that pulse diagnosis is used is assessing the relative level of Qi within and between organs if accompanying signs and symptoms indicate that the organ or phase is the problem. Rogers notes:

Five element system strives to balance the energy flow and levels of Qi, and it is therefore somewhat less effective in the presence of a strong perverse energy, or a physical blockage of Qi

Accordingly, as a system, its strength is said to lie in the treatment of diseases with an emotional or psychological origin, (irrespective of whether there are physical signs and symptoms are manifest), which respond more favourably than conditions of a primary physical cause alone (Rogers 2000).

It is also a useful approach for identifying internal imbalances deriving from impaired organ function and Qi movement identified through signs and symptoms such as lethargy, oedema, insomnia, gastric reflex, migraine and hot flushing, (as opposed to actual organic organ disease). It can additionally be useful for assessing the relative balance of Qi between the Yin and Yang partner channels of an associated phase (Box 9.10).

Box 9.10

Uses of pulse diagnosis in the Five Phase system

• Locate affected organs by assessing the changes in pulse strength at the related pulse position

• Identify the nature of the dysfunction; whether it is excess (hyperactivity or stagnation), vacuity (hypoactivity)

• Inform point selection to correct imbalances by the movement of energy

• Inform treatment affect via subsequent changes in the patient’s Qi as reflected in the pulse.

9.4.3. Application of the Five Phase pulse assumption system

This pulse assumption system is used specifically to identify imbalances reflected by relative and absolute differences in strength between and within the Zang and Fu organs via the wrist pulses. The system uses the three pulse sites Cun, Guan and Chi on each wrist at two levels of depth: superficial and deep (Box 9.11). Thus there are 12 positions, six located superficially and 6 located at the deep level of depth, with each position associated with a Zang or Fu organ.

Box 9.11

Utilising three levels of depth within Five Phase pulse diagnosis

As noted, the Five Phase pulse assessment usually uses two levels of depth: superficial and deep. However, when palpating the radial pulsation, the pulse is often felt strongest in the middle level of depth. If using the Zang Fu (organ) approach to assessing the pulses then this would likely result in a pulse interpreted as being both Yin and Yang deficient or vacuous (not to be confused with the Vacuous pulse). That is, the individual would be assessed as being in a constant state of ill health and continuously requiring treatment to address the pulse findings.

However, another way to view this is to consider the Yin and Yang in balance when the pulse occurs strongest in the middle level of depth for the associated phase. When the pulse is felt strongest at the superficial level of depth or the deep level of depth then the phase is considered out of harmony. Whether this is Yin or Yang related depends on the level of depth that the pulse is felt strongest or weakest.

The assignment of organs and associated phase or element characteristic to each of the 12 pulse positions is based on the arrangement presented in the Nan Jing (Table 9.7, Fig. 9.1, Box 9.13). Thus the six Zang or Yin organs are assigned to the deep level positions and their related Fu or Yang organs to the superficial level of the same corresponding position. For example, the left Cun position has the Heart assigned to the deep level of depth and its related Yang organ, the Small Intestine, is assigned to the superficial level of depth. The Heart and Small Intestine are assigned to the Fire element.

| Left side | Right side | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Superficial | Deep | Deep | Superficial | |

| Small intestine | Heart | Cun | Lung | Large Intestine |

| Gallbladder | Liver | Guan | Spleen | Stomach |

| Bladder | Kidney | Chi | Pericardium | Triple Heater |

| Yang | Yin | Yin | Yang | |

|

| Figure 9.1The Five Phases (Wu Xing) and their related Yin and Yang partner organs. The Sheng cycle follows each consecutive phase in a clockwise direction as indicated (solid circular line). The Ke cycle also moves in a clockwise direction moving between every second phase as indicated (dashed line in star formation). |

Box 9.13

Channel versus organ

The Five Phase system uses the Nan Jing arrangement of organs with the Small Intestine and Large Intestine located at the Cun positions, reflecting the location of these channels in the upper regions of the body (in spite of the organs being located in the lower abdomen). The Pericardium and Triple Heater are represented on the Chi position of the Lower Jiao or pelvic cavity in spite of the pericardium being located around the heart. These two ‘channels’ have theoretical and functional linkages to the Kidneys. As such this model is also termed a functional model and has a direct association with the layout of the channel network in acupuncture.

Maciocia (2004: p. 439) notes Li Shi Zhen’s arrangement of the organs and channels to the Cun, Guan and Chi pulse positions as a herbalist model. The herbalist arrangement has the SI and LI organs respectively placed at the left and right Chi positions, reflecting the anatomical layout of the body rather than the channel layout. Hence this would be called an anatomical model.

Thus the system assesses the relative and absolute strength of balance between the two levels of depth within a pulse site, the superficial and deep, comparing the balance of the Yin and Yang organ partners, as well as assessing the strength between other pulse sites and related organs.

9.4.4. Pulse assessment method

Assessment of pulse using this system primarily focuses on comparative differences in strength. This occurs discretely within each of the pulse positions when assessing relative differences in strength between the superficial and deep levels of depth. Comparative differences in strength are also required in comparing the strength of one phase to another by comparing the strength difference between the pulse positions. This generates a lot of data, so it is it is useful to use a paper-based recording method to note your assessment results. This assists in making diagnostic judgements on your findings and subsequent selection of acupuncture points.

The ‘normal’ pulse is used as a gauge to determine whether pulse strength, of the pulse generally, is appropriate or not. Physique, age, gender and level of activity are important variables in this process, assisting in determining what is normal or abnormal for the individual having their pulses assessed. With this in mind, these variables provide a range of normal pulse presentations and are always considered against the ‘normal’ pulse as described in Chapter 5 and Chapter 6. (Never subjectively assume what the ‘normal’ pulse for a patient should be.)

The five stages of the Five Phase pulse assessment method are as follows:

Step 1 Evaluation of overall pulse strength at the superficial and deep level at each pulse site

Assess each position at both the superficial and deep level of depth. Start by palpating each pulse site separately. Feel for the pulse strength at the superficial level of strength, that which corresponds to the related phase’s Yang organ, and at the deep level of depth for the Yin organ. It is best to be methodical so start at the Cun position, next feel the Guan and finally the Chi. (Refer to Chapter 5 for the location of these sites and pulse depths.) Repeat this process for the other side. When palpating the pulse you are attempting to ascertain whether:

• A pulse is present at each of the superficial and deep levels of depth for that pulse site

• The overall pulse strength, if a pulse is present at that site. Is it strong, of appropriate strength for that individual (considering their age, gender, exercise, physique) or is it weak?

For example, starting at the left Cun pulse site, the superficial level of depth is found and the strength of the pulse assessed. This position relates to the Small Intestine pulse. This is repeated at the deep level of depth. This pulse relates to the Heart. This procedure is repeated for the other positions.

Additionally, an assessment also needs to be made on whether the Yang and Yin pulses are of a similar strength for that phase/position, irrespective of whether the pulse strength is overall forceless or overall forceful. That is, are they in balance?

Step 2 Assessment of the strength between each phase

This step requires the pulse strength of one phase to be compared with the pulse strength in other phases to further identify any actual or relative differences in strength.

Step 3 Concurrently recording your pulse findings

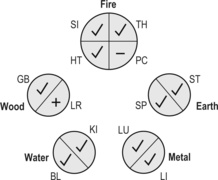

It is recommended that you write your findings down as there are twelve different ‘pulses’ that need to be assessed. Two possible methods of recording the pulse information are described here as examples: other methods are available in the relevant CM literature.

Method 1: Tabular form

Information derived in the comparative pulse assessment can be easily presented in a table format for evaluation (an example is shown in Table 9.8). This is used for diagnostic and treatment purposes, where a plus sign (+) indicates pulse strength, a minus sign indicates pulse weakness (−), and a tick (✓) indicates appropriate pulse strength. This strength assessment is undertaken separately for both the superficial and deep levels at each of the pulse positions on each wrist. More than one sign can be used to indicate a position of great strength or weakness (for example +++ or +3). Such multiple notation adds a further level of usefulness to the pulse information as it notes ‘degrees’ or difference in strength, where as the use of a single sign simply denotes a difference.

| ✓= appropriate strength; −= decreased strength (relative deficiency); += increased strength (relative excess). | ||||||||

| After Rogers (2000: p. 89), with the author’s permission. | ||||||||

| Left side | Right side | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Superficial | Deep | Deep | Superficial | |||||

| Yang | Yin | Yin | Yang | |||||

| SI | ✓ | HT | ✓ | Cun | LU | ✓ | LI | ✓ |

| GB | ✓ | LV | + | Guan | SP | ✓ | ST | ✓ |

| BL | ✓ | KD | ✓ | Chi | PC | − | TH | ✓ |

Note that the positive and negative notation is unique to the practitioner that assessed the pulse. Because of this, inter-practitioner interpretation of another’s Five Phase assessment tables needs to be approached with caution so as to not misinterpret the significance of a positive or negative notation, as the notation is generally used to denote relative, not absolute, strength differences. However, this does not exclude the practitioner from undertaking assessment of absolute strength differences, although one factor must be kept in mind: Five Phase pulse assessment is also used for assessing the relative balance of the phases and is often used for health maintenance, so changes in absolute strength (that is, force) may not be apparent. (If force changes are occurring then the Cun Kou approach to pulse assessment is likely to be more appropriate.)

The notation and subsequent pulse record generated is a subjective approach to pulse diagnosis. Because of this, it is important that the same strength notation is consistently used to note degrees of relative strength, to maintain the reliability of the method (if only for a particular practitioner).

Method 2: Five Phase diagram

The information can be transferred into a Five Phase or Wu Xing diagram to assist with the interpretation of the pulse findings and appropriate point selection (Fig. 9.2).

|

| Figure 9.2Wu Xing diagram for recording pulse assessment findings.(From Rogers 2000, with the author’s permission.) |

Step 4 Interpretation of findings

The pulse findings can be examined in a number of ways:

Within phases

Differences in strength between the Yin and Yang organs within a phase usually reflect dysfunction of the organs of the associated phase. For example, a strong Stomach pulse and weak Spleen pulse indicate the phase is imbalanced. As such treatment requires the use of the Luo points to transfer energy from the Stomach to the Spleen.

Thus a stronger pulse strength at the superficial level of depth could mean either Yin is relatively weak or Yang is in excess. Similarly, a stronger pulse strength at the deep level of depth may indicate that the Yang is weaker and the Yin is in excess.

A similarity in strength at the deep and superficial levels of depth indicates that the phase is in balance. If however the pulse overall is weak or stronger than would be expected at both levels then this is interpreted as the whole phase being deficient or in excess.

A weaker Yang pulse is considered a better prognosis than a weaker Yin, as Yin is seen as the foundational energy of the phase in the body and the Yang is an extension of the phase function. Thus a weak Yin usually indicates weak Yang but Weak Yang does not necessarily indicate weak Yin.

Yang is also more responsive to circadian rhythms, and other variables such as a poor night’s sleep or a missed meal may cause a transient decrease in pulse strength; such transient changes may be expected to occur and need not necessarily indicate any concerns.

Between phases or organs

• Positive: Move the excess into the deficient region

• Negative: Area of deficiency. If a single organ is affected, use the Yuan point

• If positive and negative: Move the excess to tonify the vacuity

• If single positive: Drain or control.

Sheng cycle

The Sheng cycle is known as the engendering or generating cycle and this is responsible for ensuring the smooth flow of Qi between the successive phases. If obstruction or stasis occurs in one phase this can impact on the next phase, reducing its access to the flow of Qi. This should be reflected in the relevant pulse positions as an excessive strength in the obstructed phase and accordingly deficient pulse strength in the subsequent phase (Fig. 9.2).

Ke cycle

As noted earlier, the Ke cycle helps to regulate the function of the organs. When this regulation becomes over rigorous, this can impact adversely on the organ or phase being controlled. This may occur when the organ being regulated is itself deficient, therefore allowing the controlling organ to affect its functions. A common example of this is the pattern of Wood attacking Spleen. This may occur when the Liver Qi becomes hyperactive, through stagnation or a result of pathogenic heat or fire. This overflows into the Earth phase, impairing the normal functioning of the Earth organs (Spleen and Stomach) resulting in a mixture of both Wood and Earth pathological signs and symptoms such as alternating constipation and loose stools, flatulence, intestinal pain and bloating. This may be reflected in the pulse as a strong Wood phase pulse with a weak Earth phase pulse.

Within an organ

Sometimes a single pulse position at either depth may be weak within a phase, without a concomitant increase in the pulse for the partner organ. This indicates deficiency within that particular organ only which has not yet begun to impact on its partner. In this case, treatment of the affected organ could be addressed by the use of the Yuan points to tonify the Qi of the deficient organ.

Step 5 Acupuncture point selection

The Five Phase system of treatment uses the command or elemental points. For the upper limb, these are located between the elbow and finger tips and for the lower limb, from the knees to the toe tips. They fall into five categories:

• Luo points: Transfer between the Yin and Yang channel partners

• Horary points: Same as the channel. For example, Wood on Wood, Earth on Earth

• Tonification points: Promote Qi

• Sedation points: Drain Qi

• Yuan points: Promote Qi in the related channel.

Generally, only the Luo points and tonification points are used to achieve the balance of energies within the Five Element system. Tonification helps to supply energy to an organ or area via the channels, while sedation in this context means to draw energy away from a hyperactive organ or area. (Rogers 2000: pp. 46-47). (For more details on the use of the Five Phase system, see Rogers 2000.)

9.4.5. Chinese clock and Five Phase pulse diagnosis

Five Phase pulse diagnosis has a few idiosyncratic variations not normally considered in other systems of pulse diagnosis. For example, the movement of the Qi ebbs through the channels with respective times of the day – the Chinese Clock or the Law of Midday-Midnight. This in effect produces a two-hourly ‘high tide’ zone of Qi, termed the horary flow, reflected in a relatively stronger pulse at the wrist for which the position correlates to the organ. Concurrently, there is also a ‘low tide’ ebb and the pulse position of the corresponding organ would be expected to have a relatively weaker pulse at that two-hourly time of the day. As such, the Zang and Fu organ positions show whether the energy flow to its particular functional area is normal, excessive or deficient. For example, at midday the Heart is said to be at its ‘strongest’ with the Qi ebb at its maximum. Concurrently, the gallbladder is at its weakest. The GB is strongest at midnight, at which time the Heart is at its lowest Qi ebb point.

The normal strength variations with the ebb and flow of Qi as described by the Chinese Clock may also be useful in identifying deficient and excess conditions during the horary flow time for the related organ. For example:

• When palpating the corresponding pulse of a organ/channel at high tide, yet the organ is weak or of ‘normal’ strength, then this can indicate vacuity

• If the organ/channel is of strong strength during low tide, than this can indicate an excess.

This approach to pulse diagnosis has relevance to the system which uses ‘open hourly points’ (na zi fa) (Fig. 9.3).

|

| Figure 9.3The Chinese Clock, and related organs. The Roman numerals stem from a European attempt to standardise the channels by number, rather than by name.(From Rogers 2000, with the author’s permission.) |

9.4.6. Pulse qualities

There are variations in the available literature on the Five Phase approach which incorporate pulse qualities in addition to simply assessing differences in strength. Such approaches are derived from the traditional descriptions of overall pulse qualities found in the Mai Jing and grafted on to assessment of channels using Five Phase pulse diagnosis. For example, such an approach proposes that a Stringlike (wiry) pulse can simultaneously occur at one position while at another position the pulse is a Short pulse, complicated by a Replete pulse in yet a third position and a Slippery pulse in the deep level at a fourth position. There are assumptive and practical problems with this approach, the most obvious of which is the manifestation of pulse ‘qualities’ forming simultaneously within the same individual’s pulse but which in fact are mutually exclusive, both by definition and by each pulse’s respective underlying formation mechanisms (see Box 9.12).

Box 9.12

Terminology within the Five Phase context

• Avoid using the terms ‘vacuous’ and ‘replete’ as these have connotations associated with the traditional CM pulse quality system and as such have a differing definition to that in the Five Phase system

• This system also uses the terms ‘excess’ and ‘deficient’ simply as generic descriptors which have no relationship to the overall pulse qualities Vacuous (empty) or Replete (full).

9.5. Nine Continent pulse system

The Nine Continent pulse system is one of the central methods of pulse diagnosis in the Nei Jing and has been included for discussion in this chapter because it still receives some coverage in the contemporary literature and is probably still used by some practitioners. The topic has been approached from a discussion perspective rather than as a prescriptive guide to its application, as with the other pulse systems covered in this chapter.

The Nei Jing is generally regarded as the earliest reference documenting the Nine Continent pulses as a distinct system of diagnosis. Although it was not the only method of pulse diagnosis, the extensive coverage it received in assessing health and illness indicates it was an important pulse system at the time. Chapter 20 of the Su Wen, ‘Treatise on the three regions and the nine subdivisions’, is central to the discourse between Huang Qi and Qi Po and the revealing of this regional pulse assessment system. The system is premised on the microcosmic arrangement of the macrocosm reflected within the body. In particular, the Nine Continent system is another application of the Heaven-Earth-Humanity theme.

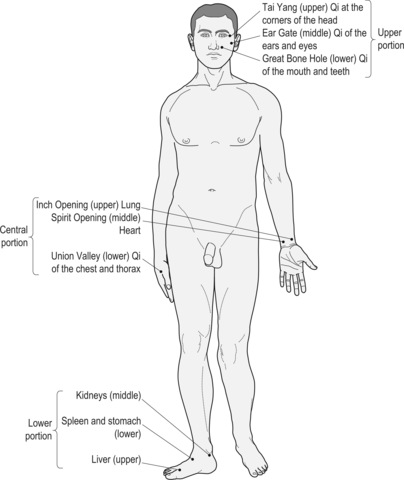

To apply this pulse system the body is first divided into three portions. In this way, components of Heaven, Earth and Humanity are simultaneously assigned to the upper, middle and lower portions or regions of the body. (Note, however, that the division is different from that used in the San Jiao system where the thoracic cavity containing the lungs and heart is the upper Heater, whereas in this system the thoracic cavity constitutes the central region.) The three regions in the Nine Continent system are:

• Upper (Heaven): From the shoulders to the head. Associated with the Qi of the head and senses: expression of the Shen

• Middle (Earth): The thoracic cavity and the upper limbs: Associated with the Lungs and Heart: movement of Qi and Blood

• Lower (Humanity): From the diaphragm to the feet. Associated with the abdominal and pelvic cavities; includes the Liver, Spleen Kidneys and Stomach organs.

Perfection to the authors of the Nei Jing required an aspect of both Heaven (Yang) and Earth (Yin) to be residing within Humanity, in each of the three regions. As such, each region is further divided into three subdivisions also correspondingly associated with the cosmological Heaven, Earth and Humanity. For example, this means there is an aspect of Heaven within Heaven, Earth within Heaven and Humanity within Heaven within the upper region. This arrangement is similarly repeated with the other two regions. It is the consequent nine subdivisions that name the Nine Continent pulse system (Table 9.9, Fig 9.4).

| Regions | Subdivision | Pulse location | Reflection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nei Jing according to Veith (1972: pp. 187–188) | |||

| Upper (Heaven) | Upper (Heaven) | Arteries on either side of forehead | Corners (temples) of the head and brow |

| Middle (Earth) | Arteries within both cheeks (jaw) | Corners of the mouth and the teeth | |

| Lower (Humanity) | Arteries in front of ears | Corners of the ears and the eyes | |

| Middle (Earth) | Upper (Heaven) | Great Yin within hands | Lungs (Po) |

| Middle (Earth) | Region of “sunlight” within hands | Breath within the breast (Zheng Qi) | |

| Lower (Humanity) | Region of lesser Yin within hands | Heart (Shen) | |

| Lower (Humanity) | Upper (Heaven) | Region of absolute Yin within the feet | Liver (Hun) |

| Middle (Earth) | Region of lesser Yin within the feet | Kidneys (Jeh) | |

| Lower (Humanity) | Region of the Great Yin within the feet | Force of life of the spleen and the stomach (Ji) | |

| Nei Jing according to Unschuld (2003: p. 254) | |||

| Upper (Heaven) | Upper (Heaven) | Moving vessels on the two sides of the forehead | Qi at the corners of the head |

| Middle (Earth) | Moving vessels on the two sides of the cheeks | Qi of mouth and the teeth | |

| Lower (Humanity) | Moving vessels in front of the ears | Qi of ears and the eyes | |

| Middle (Earth) | Upper (Heaven) | Major Yin [locations] of the hands | Lungs |

| Middle (Earth) | The Yang brilliance [locations] of the hands | Qi in the chest | |

| Lower (Humanity) | Minor Yin [locations] of the hands | Heart | |

| Lower (Humanity) | Upper (Heaven) | Ceasing Yin [locations] of the feet | Liver |

| Middle (Earth) | Minor Yin [locations] of the feet | Kidneys | |

| Lower (Humanity) | Major Yin [locations] of the feet | Qi of spleen and the stomach | |

| Nine Continent according to Maciocia (2004: p. 434) | |||

| Upper (Heaven) | Upper (Heaven) | Taiyang | Qi of the head |

| Middle (Earth) | ST 3 | Qi of the mouth | |

| Lower (Humanity) | SJ 21 | Qi of ears and eyes | |

| Middle (Earth) | Upper (Heaven) | LU 8 | Lungs |

| Middle (Earth) | LI 4 | Centre of thorax | |

| Lower (Humanity) | HR 7 | Heart | |

| Lower (Humanity) | Upper (Heaven) | LR 10: Alternative LR 3 | Liver |

| Middle (Earth) | KD 3 | Kidneys | |

| Lower (Humanity) | SP 11, Alternative ST 42 | Spleen and Stomach | |

|