Other oesophageal and gastric neoplasms

Gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GISTs)

GISTs are soft-tissue sarcomas of mesenchymal origin that arise in the gastrointestinal tract; they are rare, representing 0.1–3% of all gut tumours and 5% of all soft-tissue sarcomas.1 Historically, these tumours were considered to be of smooth muscle origin and were generally regarded as leiomyomas (benign) or leiomyosarcomas (malignant). Electron microscopy and immunohistochemical studies indicated, however, that only a minority of stromal tumours have the typical features of smooth muscle, with some having a more neural appearance and others appearing undifferentiated.2 ‘Gastrointestinal stromal tumour’ was subsequently introduced as being a more appropriate term for these neoplasms, with the variable histological features (smooth muscle, neural or undifferentiated) considered to be of little clinical relevance. Gastrointestinal autonomic nerve tumour (GANT) was also introduced to describe sarcomas with ultrastructural evidence of autonomic nervous system differentiation,3 but these tumours are now recognised as a variant of GIST.4 The discovery of CD34 expression in many GISTs suggested that they were a specific entity,5 distinct from smooth muscle tumours. It was also observed that GISTs and the interstitial cells of Cajal (ICCs) express the receptor tyrosine kinase KIT (CD117).6 This has led to the now widely accepted classification of mesenchymal tumours of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract into GISTs, true smooth muscle tumours and, far less frequently, true Schwann cell tumours.7 GISTs are microscopically classified into three histological subtypes: spindle cell (70%), epithelioid (20%) and mixed (10%). Immunohistochemically, more than 90% of GISTs stain positive for CD117. A new antibody, DOG-1, is also highly sensitive and specific for GISTs.8 The commonest sites of mutations in the c-kit gene are in exon 11 (60–70%), followed by exon 9 (18%), and exons 13 and 17 (3%). It is important that an experienced pathologist examines the immunohistochemical profile of any mesenchymal tumour as CD117-positive staining can be seen in other tumours such as seminomas, small-cell lung cancer, thyroid cancer and melanomas.

Incidence and malignant potential

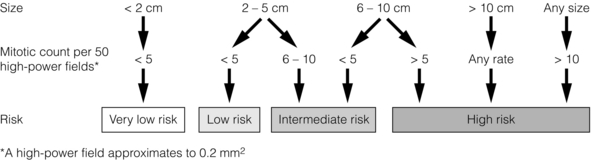

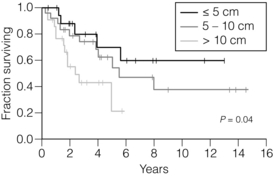

Studies using diagnostic markers including CD117 immunoreactivity have shown that GISTs are under-diagnosed.6 The morphological spectrum of GISTs was also wider than previously recognised. The estimated annual incidence of GISTs is around 15 per million,9 which equates to approximately 900 new cases per year in the UK. A true measure of the incidence, prevalence and ratio of ‘benign’ to ‘malignant’ GISTs may not be possible as these tumours appear to possess varying degrees of malignant potential. The size of the tumour, the symptoms at diagnosis, the organ of origin (small-bowel GISTs have the worst prognosis) and mitotic count seem to be the most important factors when assessing prognosis.10

Patient demographics and anatomical distribution

No marked sex difference is apparent for GISTs. Two larger series of malignant GI sarcomas did, however, demonstrate a slight male predominance.12,13 The age distribution appears to be unimodal, with a median age at presentation of 58 years (range 16–94). The peak incidence in men occurs in the fifth decade, slightly before that in women, where it peaks in the sixth decade. The median age at presentation appears constant in several series, ranging from 58 to 61 years.14 Only 1–2% of GISTs present in patients before 30 years of age.12

Most GISTs arise in the stomach or small intestine, and infrequently in the oesophagus, mesentery, omentum, colon or rectum13,15 (Table 11.1). Approximately 10–30% of GISTs are overtly malignant at presentation;16 the principal sites of metastasis are the liver and the peritoneal cavity, and spread to lymph nodes is very rare.12

Table 11.1

| Site | Percentage |

| Stomach | 60–70% |

| Small intestine | 20–30% |

| Oesophagus, mesentery, omentum, colon or rectum | 10% |

Presentation

The symptoms of GISTs are non-specific and depend on the size and location of the lesion. Small GISTs (2 cm or less) are usually asymptomatic and are detected during investigations or surgical procedures for unrelated disease. The vast majority of these are of low risk for malignancy.17 In many cases the mucosa is normal so that endoscopic biopsies are unremarkable. Incidental discovery accounts for approximately one-third of cases.18

The most common symptom is GI bleeding, which is present in approximately 50% of patients19 (Table 11.2). In addition, systemic symptoms such as fever, night sweats and weight loss are common in GIST and rare in other sarcomas. Patients with larger tumours may experience abdominal discomfort or develop a palpable mass.20 GISTs are often clinically silent until they reach a large size, bleed or rupture. Symptomatic oesophageal GISTs, although rare, typically present with dysphagia, while gastric and small-intestinal GISTs often present with vague symptoms leading to their eventual detection by gastroscopy or radiology. Most duodenal GISTs occur in the second part of the duodenum, where they push or infiltrate into the pancreas.21

Table 11.2

Symptoms of GIST at diagnosis19

| Symptoms | Incidence |

| Abdominal pain | 20–50% |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 50% |

| Gastrointestinal obstruction | 10–30% |

| Asymptomatic | 20% |

Investigation

Approximately 60% of GISTs are submucosal and grow towards the lumen where, if in the proximal GI tract, they may be visualised endoscopically as smooth submucosal projections. If a small submucosal mass is seen as an incidental finding at the time of endoscopy, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) should be the first investigation, as a significant proportion will be due to extrinsic impression from normal adjacent structures, e.g. gall bladder in the antrum, and spleen in the proximal stomach. If this is the case, no further investigation is required. For larger palpable masses, or where the patients present with haemorrhage, abdominal pain or obstruction, computed tomography (CT) is usually the first investigation after endoscopy to both assess the primary and look for metastases.22

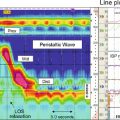

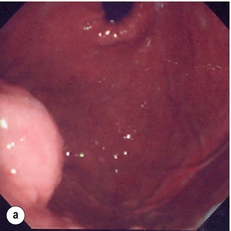

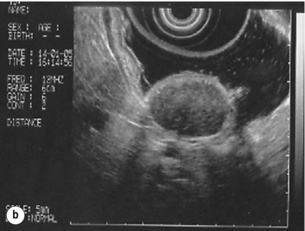

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)

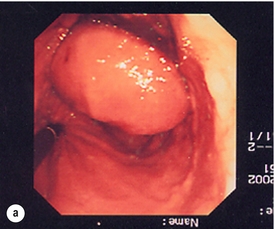

The classical features are of a hypoechoic mass contiguous with the fourth (muscularis propria) or second (muscularis mucosae) layers of the normal gut wall, both of which are hypoechoic (Fig. 11.3a,b). The EUS features most predictive of ‘benign’ tumours are regular margins, tumour size ≤ 30 mm and a homogeneous echo pattern. Larger tumours with irregular extraluminal margins and cystic spaces are more likely to behave aggressively.23,24

Figure 11.3 (a) Endoscopic view of a small incidental gastric GIST. (b) A 12-MHz EUS image of the incidental gastric GIST seen in (a), showing the lesion arising from the muscularis propria.

To further aid diagnostic accuracy it is possible to use a linear EUS scope through which needle aspirates and core biopsies can be taken without breaching surgical resection planes. EUS with fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) in experienced hands has a diagnostic accuracy of up to 97% for GIST lesions,25 is becoming more widely available and should be considered in the diagnostic work-up of a possible GIST lesion if the result could change clinical management.

CT scanning

GIST imaging by CT typically shows an extraluminal mass, often with central necrosis, arising from the digestive tract wall.18 Small tumours typically appear as sharply margined, smooth-walled, homogeneous, soft-tissue masses with moderate contrast enhancement.26 Large tumours tend to have mucosal ulceration, central necrosis and cavitation, and heterogeneous enhancement following i.v. contrast.26 As well as defining the presence and nature of a mass, if possible, the likely organ of origin should be defined. Multiplanar reconstruction can assist this, particularly with large masses. Negative oral contrast (e.g. water) and intravenous contrast for the assessment of gastric GISTs is recommended. CT of chest, abdomen and pelvis is recommended for staging of GIST, with the exception of small incidental tumours or when a patient presents as an emergency requiring urgent surgery. With regards to assessing treatment response, traditional CT criteria (RECIST criteria) have been shown to be inaccurate for measuring GIST response to imatinib and the Choi criteria are recommended (10% reduction in size and 15% reduction in density).27

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

In general, MRI offers no additional information regarding the intralesional tissue characterisation of primary GISTs. However, MRI provides excellent soft-tissue contrast resolution and direct multiplanar imaging, which can help delineate the relationships of the tumour and adjacent organs, and is useful in anorectal disease.26

Positron emission tomography (PET)

PET scanning using a standard fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-PET technique has proven extremely useful in the prediction of tumour response to the tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib (Glivec, Norvartis Pharma AG) now used in the treatment of unresectable and metastatic malignant GISTs.28 Glucose uptake of the tumours decreases within a few hours to days of the start of treatment, which can be verified with FDG-PET.17 The PET scan can be utilised to distinguish between tumour progression and increase in volume due to intratumoral bleeding. PET scan responses have also been demonstrated to predict subsequent tumour volume reductions found on CT or MRI.29

GIST syndromes

Families have been reported with single-base ‘gain of function’ mutation in the kinase domain of KIT. The resultant effect is the development of multiple GISTs in the small bowel. Diffuse hyperplasia of spindle-shaped cells within the myenteric plexus at sites unaffected by GIST formation was also noted.30,31 The association of three uncommon neoplasms – gastric GIST, functioning extra-adrenal paraganglionoma and pulmonary chondroma – was first reported in 1977 and has since been recognised as ‘Carney’s triad’ (Fig. 11.4).32 A subsequent review of 79 cases demonstrated that, unlike isolated sporadic GIST, where no significant sex difference was noted, 85% were female.33 Twenty-two per cent of the patients had all three tumours; the remainder had two of the three, usually the gastric and pulmonary lesions. Adrenocortical adenoma has since been identified as a new constituent of the disorder. The presence of two of the three main tumours is considered sufficient for the syndrome.

Treatment and prognosis (Box 11.1)

Percutaneous (ultrasound or CT) or laparoscopically guided biopsies should not be used in resectable disease due to the risk of tumour rupture or seeding, unless it may result in a change of treatment.17 Laparoscopy may be considered in the staging of large lesions to exclude peritoneal metastases but an exploratory laparotomy is usually required to decide whether a large primary tumour is technically resectable or not.

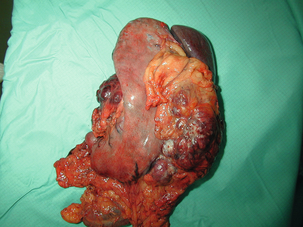

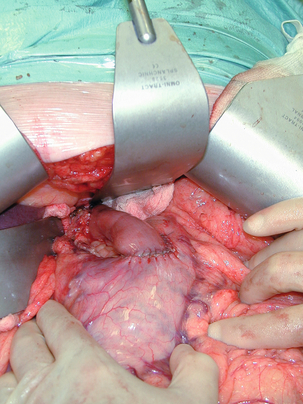

At all sites the extent of resection is therefore dictated by the size of the tumour and its location in relation to, or invasion of, adjacent structures (Fig. 11.5). Oesophagectomy is the standard procedure for oesophageal GISTs but these are very rare and submucosal lesions in the oesophagus are much more likely to be leiomyomas. EUS-FNA core biopsy from these lesions is recommended to make a preoperative diagnosis so that surgical planning is appropriate.25 Oesophageal GISTs and leiomyosarcomas require an oesophagectomy whereas leiomyomas can safely be enucleated without removing the oesophagus.

Figure 11.5 Operative specimen following en bloc total gastrectomy, splenectomy and distal pancreatectomy for locally advanced GIST.

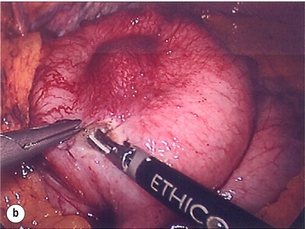

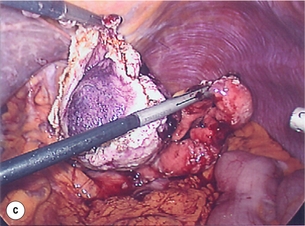

In the stomach, R0 resection may involve a partial, subtotal or total gastrectomy, although ‘wedge’ excision and ‘sleeve’ resections are also frequently performed to preserve as much stomach as possible. Small gastric lesions lend themselves well to laparoscopic resection (Fig. 11.6a–c). Resection of GIST tumours arising at the gastro-oesophageal junction creates particular problems as a poor quality of life may result from simple excision with anastomosis of stomach to oesophagus. Alternatively, reconstruction using a short jejunal interposition should be considered for these patients, the ‘Merendino procedure’ (Fig. 11.7),36 as it results in a better quality of life compared to an oesophagogastric anastomosis.37 The most important factors, as stated, are that the tumour is not ruptured and that negative resection margins are obtained. Simple enucleation of the tumour is inadequate as these lesions do not possess a true capsule. Direct invasion of adjacent structures occurs in 10–15% of GISTs and surgery in such cases should include en bloc resection of involved adjacent organs.12,14 Nodal metastases are extremely rare and routine extended lymph node dissection is therefore unjustified.38

Figure 11.6 (a) Endoscopic view of a moderate-sized gastric fundal GIST. (b) Laparoscopic image of the lesion seen in (a). (c) Completed harmonic scalpel dissection of the gastric GIST in (a) prior to removal of specimen in a retrieval bag and closure of the resulting gastric defect with a linear EndoGIA stapler.

Figure 11.7 Completed Merendino procedure showing distal anastomosis between the jejunal interposition and the stomach.

As very few studies address the issue of GISTs found incidentally, there are no clear data to support one definitive management plan over another. In their study of 39 GISTs, which included 16 identified incidentally, Ludwig and Traverso concluded that as a consequence of the frequency of serious complications in symptomatic patients, complete excision should also be recommended for asymptomatic patients.39 However, the UK guidelines for the management of GISTs recommend that small asymptomatic incidental lesions can be treated conservatively, particularly if serial examination shows no change in size over 1–2 years.40 However, there are no long-term studies of the natural history of these lesions, and surgeons should explain these uncertainties to their patients and discuss the pros and cons of resection before proceeding to surgery. In patients with borderline fitness for resection, or those who decline surgery at initial presentation, monitoring the lesion with EUS and/or CT for evidence of enlargement is acceptable so long as the results of surveillance influence the final management.

Imatinib

Imatinib mesylate is a receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor that inhibits the constitutively activated tyrosine kinases of ABL (including the stable transfection product fusion kinase BCR-ABL seen in chronic myeloid leukaemia), platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) and KIT. The drug is administered orally, and its use, dosage and side-effect profile are well established following use in the treatment of chronic myeloid leukaemia. It has very little effect on normal cells, where the kinase is not constitutively active. Experiments on human tumour cell lines dependent upon the KIT pathway demonstrate that imatinib blocks the kinase activity of KIT, arrests proliferation and causes apoptotic cell death.41 Imatinib is generally well tolerated, although most patients experience some mild or moderate adverse events. Serious adverse events occur in around 20% of patients, the most serious of which is life-threatening tumour haemorrhage in approximately 5%.

Unresectable or metastatic disease

Prior to the introduction of imatinib mesylate, patients with advanced GISTs faced severe morbidity and short life expectancy. Untreated, the median overall survival for unresectable or metastatic disease is around 12 months (ranging from 2 to 20 months).42 Conventional chemotherapy and radiotherapy is ineffective in patients with metastatic GISTs.43

Early phase 1 studies of imatinib (then coded ST1571) took the oncology world by storm.44 Never before had response rates of 80–90% been seen in metastatic sarcomas and a new era of ‘smart’ compounds was born. Over 50% of patients with metastatic or unresectable GISTs will survive more than 5 years if treated with imatinib.

Although 80% of GISTs respond to imatinib, 20% demonstrate initial resistance to the drug and, of those that respond initially, some will develop late resistance.48

Adjuvant therapy post-resection

Surgery has a limited role in metastatic disease except when patients present with low-volume liver metastases; about a third of such patients may be cured by hepatic resection.51 In selected patients with large incurable tumours, surgery may play a limited role in palliation of symptoms, but whether to operate is best decided by a multidisciplinary team who have expertise in GIST management.52 Downsizing of unresectable primary tumours and hepatic metastasis following treatment with imatinib can render lesions resectable, but long-term survival is uncommon, particularly if imatinib resistance has developed.53 Randomised studies in the USA and Europe are under way to assess the value of neoadjuvant imatinib for unresectable GISTs that might be rendered resectable (and potentially curable).

Gastric lymphoma

Primary gastric lymphoma is rare, accounting for about 5% of gastric tumours but one of the commonest sites for ‘extranodal’ lymphoma.54 It is twice as common in men as in women and median age of diagnosis is 60–65 years,55,56 except in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected patients, who develop the disease earlier.57 It often presents with the same non-specific signs of dyspepsia and vague epigastric discomfort seen in both benign peptic ulceration and gastric adenocarcinoma. However, it may take longer than epithelial cancer to grow and cause persistent pain and weight loss. Diagnosis is by endoscopy and biopsy. It is essential that patients who fulfil the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) criteria for urgent upper GI endoscopy are referred and that the endoscopist performs a thorough investigation and takes adequate diagnostic biopsies.58 If the biopsies are non-diagnostic they should be repeated immediately; accurate histological diagnosis is essential as the treatment and prognosis of gastric lymphoma is very different from adenocarcinoma.

Staging

Once a diagnosis of gastric lymphoma is made the paient should undergo a CT scan of chest, abdomen and pelvis, an endoluminal ultrasound (EUS), as this is the most accurate way of assessing depth of invasion and regional node involvement,59,60 and a bone marrow aspirate to look for distant spread of the disease. Many staging systems have been employed over the years but the most clinically useful is the modified Blackledge system61 (Table 11.3).

Table 11.3

Modified Blackledge system for staging gastrointestinal lymphoma61

| Stage I | Tumour confined to GI tract without serosal penetration: Single primary or multiple non-contiguous lesions |

| Stage II | Tumour extends into abdomen nodes from the primary: II1 Local nodes (regional gastric) II2 Distant nodes (para-aortic or intercaval) |

| Stage IIE | Perforation of the serosa with involvement of adjacent structures: e.g. stage IIE (pancreas) or stage IIE (colon) Also patients who present with perforated tumours and peritonitis |

| Stage IV | Disseminated extranodal disease (lung, bone marrow, etc.) or supradiaphragmatic nodal involvement |

Classification

Low-grade MALT lymphomas arise from the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue, hence MALT, and behave in an indolent fashion. The WHO classifies MALT as extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphomas and they are a form of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.58,62,63 Men and women are equally affected and they account for about 4% of all gastric tumours and 50% of gastric lymphomas.64,65

Histopathologically they can be difficult to differentiate from chronic gastritis and experienced pathologists will look for lymphoepithelial lesions that are diagnostic.68 Treatment of stage I disease is with HP eradication and 6-monthly endoscopic biopsy for 2 years. More advanced tumours, those that persist after HP eradication or those that recur are treated with chlorambucil and rituximab, and those with large-cell transformation require CHOP chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisolone) and rituximab.69,70 Surgery is very rarely indicated for low-grade MALT lymphomas.

High-grade MALT lymphomas and diffuse B-cell lymphomas do not regress with HP eradication. Histologically they consist of sheets of destructive blast cells, do not contain lymphoepithelial lesions, and have frequent mitoses and apoptotic bodies.71 They may resemble diffuse carcinomas, sarcomas, T-cell lymphomas and even metastatic melanoma.

Surgery, therefore, has a limited role in the modern management of gastric lymphoma.74 It is used for resection of locoregional disease if medical treatment fails or in the emergency setting for bleeding or perforation.

Neuroendocrine gastroenteropancreatic tumours (GEP-NETs)

GEP-NETs are classified into intestinal neuroendocrine tumours (carcinoids), accounting for about two-thirds, and pancreatic endocrine tumours (PETs), accounting for the remaining one-third. Gastric carcinoid tumours make up just under 2% of all gastric neoplasms and there is some evidence that the incidence has been rising over the past two to three decades.75 The appendix is the commonest site for carcinoid tumours (48%), followed by the rectum (17%) and the ileum (12%); the stomach only accounts for 9%.76,77 Carcinoid tumours have characteristic histological and ultrastructural features and contain chromogranin A (CgA).77 They were first described by Oberndorfer in 1907, who named them ‘karzinoide’, meaning ‘carcinoma-like’ in recognition of their more benign behaviour compared to adenocarcinomas.78 Gastric carcinoids arise from histamine-containing enterochromaffin-like (ECL) cells, which are found in the fundus and body of the stomach. Gastric acid is produced by parietal cells when they are stimulated by gastrin directly (secreted by the G cells in the gastric antrum) or by histamine released locally by ECL cells when these are stimulated by gastrin. Negative feedback is provided by D cells that release somatostatin (SST) when stimulated by rising luminal H+ concentrations; SST binds to G cells and ECL cells and inhibits the production of gastrin and histamine, respectively, hence reducing stimulation to parietal cells to produce acid. In patients with chronic atrophic gastritis the lack of acid production by parietal cells results in decreased SST levels, with excess production of gastrin and an over-stimulation of ECL cells. As gastrin is trophic to ECL cells, this can lead to ECL hyperplasia, dysplasia and eventually carcinoid tumour.

Presentation, classification and treatment

Gastric carcinoids are often discovered incidentally during upper GI endoscopy. Alternatively, they may present with bleeding (iron deficiency anaemia or frank GI blood loss), abdominal pain or dyspepsia. Rarely, they present late with metastatic disease and symptoms from the release of bioactive substances. Atypical carcinoid syndrome is due to histamine release and presents with a patchy cutaneous flush, oedema, watering eyes, bronchoconstriction and headaches, whereas classical carcinoid syndrome presents with cutaneous flushing, bronchospasm and diarrhoea, and is probably due to circulating serotonin and tachykinins.79 Diagnosis is made by histology of endoscopic biopsies and the argyrophil reaction with the presence of CgA mRNA or protein.80 Raised plasma CgA is a very sensitive and specific test for diagnosing metastatic carcinoid in patients with suspected carcinoid syndrome.77 Initial staging is by EUS and CT. Gastric carcinoid tumours express somatostatin-2 receptors and these will bind the synthetic octapeptide, octreotide; radiolabelled octreotide is used in the OctreoScan™.

There are a number of different classification systems for GEP-NETs. The WHO classification separates tumours on the basis of differentiation; the European Neuroendocrine Tumour Society (ENETS) classification has three groups (G1-3) based upon mitotic count and Ki67 index; and the TNM classification separates tumours according to the extent of the local tumour, regional lymph nodes and distant metastases (Tis-4, N0–1, M0–1).82 Gastric carcinoids are usefully classified according to their behaviour and are rare under the age of 50 years.83 Type I tumours are the commonest (75%), arise in patients with chronic atrophic gastritis (often those with pernicious anaemia) and are more common in women than men (3:1). They are usually small, well-differentiated polypoid lesions that behave in a benign fashion but, when larger (1–2 cm), can occasionally metastasise to regional lymph nodes. Small lesions (< 1 cm) can be removed by endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), although long-term follow-up for this treatment is lacking.

Type II gastric carcinoids are rare (8%) and occur in patients with a gastrinoma as part of the autosomal dominant disorder multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 1 (MEN-1). They have an intermediate behaviour between type I and type III carcinoids, with a 10–30% risk of metastasising. For early lesions the treatment is the same as for type I tumours, although great care should be taken to find and remove the gastrinoma whenever possible. Prognosis is again good, with about 70% 5-year survival, but the MEN-1 syndrome dictates outcome more than the carcinoid tumour.85

For patients with symptomatic metastatic carcinoid the initial treatment of choice is with somatastatin analogues such as octreotide or lanreotide, which is longer acting.85 Phase II trials of the monoclonal antibody bevacizumab89 have shown promise and phase III studies are now awaited. Surgery can play an important role in the management of metastatic GEP-NETs by reducing tumour mass (debulking) and can occasionally be curative when an R0 resection is possible, particularly for liver metastases.90 Radiofrequency ablation and embolisation/chemoembolisation can similarly be used with success to treat isolated hepatic lesions.

Rarities

Leiomyomas are benign smooth muscle tumours of the upper GI tract, are usually located in the oesophagus and may be very large at presentation.91 They may present as an incidental submucosal swelling found at endoscopy or with dysphagia or, rarely, with GI bleeding. Similar lesions found in the stomach are nearly always GISTs. Incidental leiomyomas of the oesophagus can be treated conservatively, although an EUS to confirm the diagnosis is recommended and a follow-up EUS examination 1–2 years later will provide reassurance that the lesion is not growing. Symptomatic leiomyomas can be excised by dividing the muscularis propria and enucleating the lesion without disrupting the mucosa. This is usually done now using minimally invasive techniques (thoracoscopically).92 Leiomyosarcomas look exactly like their benign counterparts but behave differently. A large submucosal lesion in the oesophagus (> 2 cm) or one that is enlarging rapidly should be treated as potentially malignant. EUS-guided fine-needle or core biopsy of such a lesion is now possible and should be attempted if leiomyosarcoma is suspected.93 If confirmed, or doubt continues after biopsy, a formal oesophagectomy is recommended, as long-term survival is dependent upon achieving an R0 resection.94

Small-cell carcinoma of the oesophagus is thankfully rare. It has an even worse prognosis than squamous or adenocarcinoma. As with most oesophageal tumours it presents late and has already spread to locoregional nodes when diagnosed.95 Even radical surgery with three-field lymph node resection results in 5-year survival of less than 10%. Treatment should therefore be by chemoradiation as this will occasionally result in a cure and, if it does not, provides moderately good palliation with less morbidity than radical surgery. There are no randomised studies of treatment but much has been extrapolated from experience with small-cell tumours of the lung.

References

1. Rossi, C.R., Mocellin, S., Mencarelli, R., et al, Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: from a surgical to a molecular approach. Int J Cancer. 2003;107(2):171–176. 12949790

2. Mazur, M.T., Clark, H.B., Gastric stromal tumors. Reappraisal of histogenesis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1983;7(6):507–519. 6625048

3. Walker, P., Dvorak, A.M., Gastrointestinal autonomic nerve (GAN) tumor. Ultrastructural evidence for a newly recognized entity. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1986;110(4):309–316. 3006627

4. Lee, J.R., Joshi, V., Griffin, J.W., Jr., et al, Gastrointestinal autonomic nerve tumor: immunohistochemical and molecular identity with gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25(8):979–987. 11474281

5. Romert, P., Mikkelsen, H.B., c-kit immunoreactive interstitial cells of Cajal in the human small and large intestine. Histochem Cell Biol. 1998;109(3):195–202. 9541467

6. Kindblom, L.G., Remotti, H.E., Aldenborg, F., et al, Gastrointestinal pacemaker cell tumor (GIPACT): gastrointestinal stromal tumors show phenotypic characteristics of the interstitial cells of Cajal. Am J Pathol. 1998;152(5):1259–1269. 9588894

7. Joensuu, H., Kindblom, L.G., Gastrointestinal stromal tumors – a review. Acta Orthop Scand. 2004;75(311):62–71. 15188667

8. Kim, K.H., Nelson, S.D., Kim, D.H., et al, Diagnostic relevance of overexpressions of PKC-theta and DOG-1 and KIT/PDGFRA gene mutations in extragastrointestinal stromal tumors: a Korean six-centers study of 28 cases. Anticancer Res. 2012;32(3):923–937. 22399613

9. Nilsson, B., Bumming, P., Meis-Kindblom, J.M., et al, Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: the incidence, prevalence, clinical course, and prognostication in the preimatinib mesylate era – a population-based study in western Sweden. Cancer. 2005;103(4):821–829. 15648083

10. Hassan, I., You, Y.N., Shyyan, R., et al, Surgically managed gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a comparative and prognostic analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15(1):52–59. 18000711

11. Fletcher, C.D., Berman, J.J., Corless, C., et al, Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a consensus approach. Hum Pathol. 2002;33(5):459–465. 12094370

12. DeMatteo, R.P., Lewis, J.J., Leung, D., et al, Two hundred gastrointestinal stromal tumors: recurrence patterns and prognostic factors for survival. Ann Surg. 2000;231(1):51–58. 10636102

13. Emory, T.S., Sobin, L.H., Lukes, L., et al, Prognosis of gastrointestinal smooth-muscle (stromal) tumors: dependence on anatomic site. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23(1):82–87. 9888707

14. Langer, C., Gunawan, B., Schuler, P., et al, Prognostic factors influencing surgical management and outcome of gastrointestinal stromal tumours. Br J Surg. 2003;90(3):332–339. 12594669

15. Lee, Y.T., Leiomyosarcoma of the gastro-intestinal tract: general pattern of metastasis and recurrence. Cancer Treat Rev. 1983;10(2):91–101. 6347377

16. Miettinen, M., El-Rifai, W., Sobin, L.H., et al, Evaluation of malignancy and prognosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a review. Hum Pathol. 2002;33(5):478–483. 12094372

17. Connolly, E.M., Gaffney, E., Reynolds, J.V., Gastrointestinal stromal tumours. Br J Surg. 2003;90(10):1178–1186. 14515284

18. Bucher, P., Villiger, P., Egger, J.F., et al, Management of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: from diagnosis to treatment. Swiss Med Wkly. 2004;134(11–12):145–153. 15106018

19. Lehnert, T., Gastrointestinal sarcoma (GIST) – a review of surgical management. Ann Chir Gynaecol. 1998;87(4):297–305. 9891770

20. DeMatteo, R.P., The GIST of targeted cancer therapy: a tumor (gastrointestinal stromal tumor), a mutated gene (c-kit), and a molecular inhibitor (STI571). Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9(9):831–839. 12417503

21. Berman, J., O’Leary, T.J., Gastrointestinal stromal tumor workshop. Hum Pathol. 2001;32(6):578–582. 11431711

22. Joensuu, H., Fletcher, C., Dimitrijevic, S., et al, Management of malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumours. Lancet Oncol. 2002;3(11):655–664. 12424067

23. Palazzo, L., Landi, B., Cellier, C., et al, Endosonographic features predictive of benign and malignant gastrointestinal stromal cell tumours. Gut. 2000;46(1):88–92. 10601061

24. Chak, A., Canto, M.I., Rosch, T., et al, Endosonographic differentiation of benign and malignant stromal cell tumors. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;45(6):468–473. 9199902

25. Akahoshi, K., Sumida, Y., Matsui, N., et al, Preoperative diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumor by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13(14):2077–2082. 17465451

26. Lau, S., Tam, K.F., Kam, C.K., et al, Imaging of gastrointestinal stromal tumour (GIST). Clin Radiol. 2004;59(6):487–498. 15145718

27. Benjamin, R.S., Choi, H., Macapinlac, H.A., et al, We should desist using RECIST, at least in GIST. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(13):1760–1764. 17470866

28. Antoch, G., Kanja, J., Bauer, S., et al, Comparison of PET, CT, and dual-modality PET/CT imaging for monitoring of imatinib (STI571) therapy in patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Nucl Med. 2004;45(3):357–365. 15001674

29. Stroobants, S., Goeminne, J., Seegers, M., et al, 18FDG-Positron emission tomography for the early prediction of response in advanced soft tissue sarcoma treated with imatinib mesylate (Glivec). Eur J Cancer. 2003;39(14):2012–2020. 12957455

30. Isozaki, K., Terris, B., Belghiti, J., et al, Germline-activating mutation in the kinase domain of KIT gene in familial gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Am J Pathol. 2000;157(5):1581–1585. 11073817

31. O’Brien, P., Kapusta, L., Dardick, I., et al, Multiple familial gastrointestinal autonomic nerve tumors and small intestinal neuronal dysplasia. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23(2):198–204. 9989847

32. Carney, J.A., Sheps, S.G., Go, V.L., et al, The triad of gastric leiomyosarcoma, functioning extra-adrenal paraganglioma and pulmonary chondroma. N Engl J Med. 1977;296(26):1517–1518. 865533

33. Carney, J.A., Gastric stromal sarcoma, pulmonary chondroma, and extra-adrenal paraganglioma (Carney Triad): natural history, adrenocortical component, and possible familial occurrence. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999;74(6):543–552. 10377927

34. Demetri, G.D., Benjamin, R.S., Blanke, C.D., et al, NCCN Task Force report: management of patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) – update of the NCCN clinical practice guidelines. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2007;5(Suppl. 2):S1–30. 17624289

35. Ng, E.H., Pollock, R.E., Romsdahl, M.M., Prognostic implications of patterns of failure for gastrointestinal leiomyosarcomas. Cancer. 1992;69(6):1334–1341. 1540870

36. Merendino, K.A., Thomas, G.I., The jejunal interposition operation for substitution of the esophagogastric sphincter; present status. Surgery. 1958;44(6):1112–1115. 13624976

37. Stein, H.J., Feith, M., Mueller, J., et al, Limited resection for early adenocarcinoma in Barrett’s esophagus. Ann Surg. 2000;232(6):733–742. 11088068

38. Dematteo, R.P., Heinrich, M.C., El-Rifai, W.M., et al, Clinical management of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: before and after STI-571. Hum Pathol. 2002;33(5):466–477. 12094371

39. Ludwig, D.J., Traverso, L.W., Gut stromal tumors and their clinical behavior. Am J Surg. 1997;173(5):390–394. 9168073

40. UK GIST Consensus Group Guidelines for the management of gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GISTs). 2005 Available from. http://www.augis.org [[accessed 03.11.12]].

41. Tuveson, D.A., Willis, N.A., Jacks, T., et al, STI571 inactivation of the gastrointestinal stromal tumor c-KIT oncoprotein: biological and clinical implications. Oncogene. 2001;20(36):5054–5058. 11526490

42. Katz, S.C., DeMatteo, R.P., Gastrointestinal stromal tumors and leiomyosarcomas. J Surg Oncol. 2008;97(4):350–359. 18286477

43. Van Glabbeke, M., van Oosterom, A.T., Oosterhuis, J.W., et al, Prognostic factors for the outcome of chemotherapy in advanced soft tissue sarcoma: an analysis of 2,185 patients treated with anthracycline- containing first-line regimens – a European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Soft Tissue and Bone Sarcoma Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(1):150–157. 10458228

44. van Oosterom, A.T., Judson, I., Verweij, J., et al, Safety and efficacy of imatinib (STI571) in metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumours: a phase I study. Lancet. 2001;358(9291):1421–1423. 11705489

45. Blanke, C.D., Demetri, G.D., von Mehren, M., et al, Long-term results from a randomized phase II trial of standard- versus higher-dose imatinib mesylate for patients with unresectable or metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors expressing KIT. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(4):620–625. 18235121

46. Blanke, C.D., Rankin, C., Demetri, G.D., et al, Phase III randomized, intergroup trial assessing imatinib mesylate at two dose levels in patients with unresectable or metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors expressing the kit receptor tyrosine kinase: S0033. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(4):626–632. 18235122 A randomised study of 400 mg vs 800 mg imatinib in unresectable or metastatic GIST. No difference was found in median survival between the two groups.

47. Verweij, J., Casali, P.G., Zalcberg, J., et al, Progression-free survival in gastrointestinal stromal tumours with high-dose imatinib: randomised trial. Lancet. 2004;364(9440):1127–1134. 15451219 Another randomised study (946 patients) comparing 800 mg with 400 mg imatinib found some small improvement in progression-free survival for the higher dose.

48. Van Glabbeke, M., Verweij, J., Casali, P.G., et al, Initial and late resistance to imatinib in advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors are predicted by different prognostic factors: a European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer–Italian Sarcoma Group–Australasian Gastrointestinal Trials Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(24):5795–5804. 16110036

49. DeMatteo, R.P., Ballman, K.V., Antonescu, C.R., et al, Adjuvant imatinib mesylate after resection of localised, primary gastrointestinal stromal tumour: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;373(9669):1097–1104. 19303137

50. Joensuu, H., Eriksson, M., Sundby Hall, K., et al, One vs three years of adjuvant imatinib for operable gastrointestinal stromal tumor: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;307(12):1265–1272. 22453568

51. DeMatteo, R.P., Shah, A., Fong, Y., et al, Results of hepatic resection for sarcoma metastatic to liver. Ann Surg. 2001;234(4):540–548. 11573047

52. Barnes, G., Bulusu, V.R., Hardwick, R.H., et al, A review of the surgical management of metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GISTs) on imatinib mesylate (Glivec). Int J Surg. 2005;3(3):206–212. 17462285

53. Sym, S.J., Ryu, M.H., Lee, J.L., et al, Surgical intervention following imatinib treatment in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs). J Surg Oncol. 2008;98(1):27–33. 18452195

54. Sandler, R.S., Has primary gastric lymphoma become more common? J Clin Gastroenterol. 1984;6(2):101–107. 6715847

55. Cogliatti, S.B., Schmid, U., Schumacher, U., et al, Primary B-cell gastric lymphoma: a clinicopathological study of 145 patients. Gastroenterology. 1991;101(5):1159–1170. 1936785

56. Weingrad, D.N., Decosse, J.J., Sherlock, P., et al, Primary gastrointestinal lymphoma: a 30-year review. Cancer. 1982;49(6):1258–1265. 7059947

57. Imrie, K.R., Sawka, C.A., Kutas, G., et al, HIV-associated lymphoma of the gastrointestinal tract: the University of Toronto AIDS-Lymphoma Study Group experience. Leuk Lymphoma. 1995;16(3–4):343–349. 7719241

58. Stolte, M., Helicobacter pylori gastritis and gastric MALT-lymphoma. Lancet. 1992;339(8795):745–746. 1347611

59. Caletti, G., Fusaroli, P., Togliani, T., et al, Endosonography in gastric lymphoma and large gastric folds. Eur J Ultrasound. 2000;11(1):31–40. 10717512

60. Yucel, C., Ozdemir, H., Isik, S., Role of endosonography in the evaluation of gastric malignancies. J Ultrasound Med. 1999;18(4):283–288. 10206216

61. Rohatiner, A., d’Amore, F., Coiffier, B., et al, Report on a workshop convened to discuss the pathological and staging classifications of gastrointestinal tract lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 1994;5(5):397–400. 8075046

62. Isaacson, P., Wright, D.H., Extranodal malignant lymphoma arising from mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. Cancer. 1984;53(11):2515–2524. 6424928

63. Parsonnet, J., Hansen, S., Rodriguez, L., et al, Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(18):1267–1271. 8145781

64. Shimm, D.S., Dosoretz, D.E., Anderson, T., et al, Primary gastric lymphoma. An analysis with emphasis on prognostic factors and radiation therapy. Cancer. 1983;52(11):2044–2048. 6627215

65. Sutherland, A.G., Kennedy, M., Anderson, D.N., et al, Gastric lymphoma in Grampian Region: presentation, treatment and outcome. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1996;41(3):143–147. 8763174

66. Pinotti, G., Zucca, E., Roggero, E., et al, Clinical features, treatment and outcome in a series of 93 patients with low-grade gastric MALT lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 1997;26(5–6):527–537. 9389360

67. Montalban, C., Manzanal, A., Boixeda, D., et al, Treatment of low-grade gastric MALT lymphoma with Helicobacter pylori eradication. Lancet. 1995;345(8952):798–799. 7891510

68. Chan, J.K., Gastrointestinal lymphomas: an overview with emphasis on new findings and diagnostic problems. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1996;13(4):260–296. 8946607

69. Raderer, M., Chott, A., Drach, J., et al, Chemotherapy for management of localised high-grade gastric B-cell lymphoma: how much is necessary? Ann Oncol. 2002;13(7):1094–1098. 12176789

70. Wohrer, S., Puspok, A., Drach, J., et al, Rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone (R-CHOP) for treatment of early-stage gastric diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2004;15(7):1086–1090. 15205203

71. Hiyama, T., Haruma, K., Kitadai, Y., et al, Clinicopathological features of gastric mucosa- associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma: a comparison with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma without a mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma component. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;16(7):734–739. 11446880

72. Coiffier, B., Lepage, E., Briere, J., et al, CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CHOP alone in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(4):235–242. 11807147 A randomised study investigating the value of rituximab when added to standard chemotherapy for treating gastric lymphoma.

73. Aviles, A., Nambo, M.J., Neri, N., et al, The role of surgery in primary gastric lymphoma: results of a controlled clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2004;240(1):44–50. 15213617 A large and important study randomising 589 patients to four treatment arms. Surgery did not improve survival and CHOP chemotherapy came out on top.

74. Popescu, R.A., Wotherspoon, A.C., Cunningham, D., et al, Surgery plus chemotherapy or chemotherapy alone for primary intermediate- and high-grade gastric non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: the Royal Marsden Hospital experience. Eur J Cancer. 1999;35(6):928–934. 10533473

75. Hodgson, N., Koniaris, L.G., Livingstone, A.S., et al, Gastric carcinoids: a temporal increase with proton pump introduction. Surg Endosc. 2005;19(12):1610–1612. 16211437

76. Berge, T., Linell, F., Carcinoid tumours. Frequency in a defined population during a 12-year period. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1976;84(4):322–330. 961424

77. Kidd, M., Modlin, I.M., Mane, S.M., et al, RT–PCR detection of chromogranin A: a new standard in the identification of neuroendocrine tumor disease. Ann Surg. 2006;243(2):273–280. 16432362

78. Oberndorfer, S. Karzinoid tumoren des dunndarms. Frankf Z Pathol. 1907; 1:237–240.

79. Conlon, J.M., Deacon, C.F., Richter, G., et al, Circulating tachykinins (substance P, neurokinin A, neuropeptide K) and the carcinoid flush. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1987;22(1):97–105. 2882598

80. Nobels, F.R., Kwekkeboom, D.J., Coopmans, W., et al, Chromogranin A as serum marker for neuroendocrine neoplasia: comparison with neuron-specific enolase and the alpha-subunit of glycoprotein hormones. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82(8):2622–2628. 9253344

81. Gibril, F., Reynolds, J.C., Lubensky, I.A., et al, Ability of somatostatin receptor scintigraphy to identify patients with gastric carcinoids: a prospective study. J Nucl Med. 2000;41(10):1646–1656. 11037994 A blinded prospective study of 162 patients with Zollinger–Ellison syndrome comparing the results of radionuclear studies with gastric biopsies looking for gastric carcinoid tumours.

82. Oberg, K., Akerstrom, G., Rindi, G., et al, Neuroendocrine gastroenteropancreatic tumours: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(Suppl. 5):v223–v227. 20555086

83. Modlin, I.M., Kidd, M., Latich, I., et al, Current status of gastrointestinal carcinoids. Gastroenterology. 2005;128(6):1717–1751. 15887161

84. Dakin, G.F., Warner, R.R., Pomp, A., et al, Presentation, treatment, and outcome of type 1 gastric carcinoid tumors. J Surg Oncol. 2006;93(5):368–372. 16550587

85. Modlin, I.M., Latich, I., Kidd, M., et al, Therapeutic options for gastrointestinal carcinoids. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4(5):526–547. 16630755

86. Rindi, G., Clinicopathologic aspects of gastric neuroendocrine tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19(Suppl. 1):S20–S29. 7762736

87. Modlin, I.M., Kidd, M., Lye, K.D., Biology and management of gastric carcinoid tumours: a review. Eur J Surg. 2002;168(12):669–683. 15362575

88. Modlin, I.M., Lye, K.D., Kidd, M., A 50-year analysis of 562 gastric carcinoids: small tumor or larger problem? Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(1):23–32. 14687136

89. Yao, J.C., Phan, A., Hoff, P.M., et al, Targeting vascular endothelial growth factor in advanced carcinoid tumor: a random assignment phase II study of depot octreotide with bevacizumab and pegylated interferon alpha-2b. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(8):1316–1323. 18323556

90. Akerstrom, G., Hellman, P., Surgery on neuroendocrine tumours. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;21(1):87–109. 17382267

91. Pompeo, E., Francioni, F., Pappalardo, G., et al, Giant leiomyoma of the oesophagus and cardia. Diagnostic and therapeutic considerations: case report and literature review. Scand Cardiovasc J. 1997;31(6):361–364. 9455786

92. Roviaro, G.C., Maciocco, M., Varoli, F., et al, Videothoracoscopic treatment of oesophageal leiomyoma. Thorax. 1998;53(3):190–192. 9659354

93. Stelow, E.B., Jones, D.R., Shami, V.M., Esophageal leiomyosarcoma diagnosed by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration. Diagn Cytopathol. 2007;35(3):167–170. 17415921

94. Rocco, G., Trastek, V.F., Deschamps, C., et al, Leiomyosarcoma of the esophagus: results of surgical treatment. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;66(3):894–897. 9768947

95. Yun, J.P., Zhang, M.F., Hou, J.H., et al, Primary small cell carcinoma of the esophagus: clinicopathological and immunohistochemical features of 21 cases. BMC Cancer 2007; 7:38. 17335582