Other leukaemias

Hairy cell leukaemia

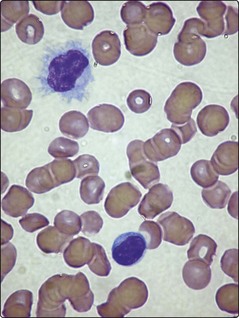

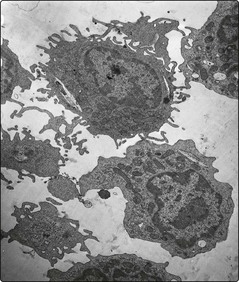

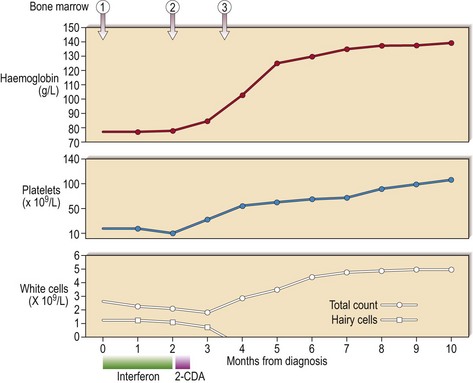

Hairy cell leukaemia (HCL) is a rare chronic B-cell leukaemia characterised by distinctive biological features and unusual sensitivity to treatment. The name of the disease is a reference to the distinctive appearance of the malignant cell (Figs 24.1 and 24.2).

Adult T-cell leukaemia lymphoma

The disease is mostly seen in areas endemic for HTLV-1, notably in parts of Japan and in the islands of the Caribbean. There is a long latent period from infection to overt disease and less than 5% of infected people actually develop ATLL. Patients most commonly present in the fifth decade and, as its name suggests, ATLL may behave as a leukaemia or a lymphoma. In the most acute form presentation is with a frank leukaemia. The malignant cells in the blood are pleomorphic but often have very irregular polylobulated nuclei. Even within the leukaemic group there is great heterogeneity with chronic and smouldering forms. In 25% of cases the disease is better described as a lymphoma as there is no demonstrable blood involvement. Despite the variability of the pathology there are well-defined clinical and laboratory features which should prompt consideration of the diagnosis, particularly in a person from an HTLV-1 endemic area (Table 24.1). In practice, lymphoma-type ATLL may be confused with other forms of T-non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Leukaemic ATLL must be distinguished from Sezary syndrome, a lymphoproliferative disorder with circulating T-cells and skin changes including erythroderma and exfoliative dermatitis.

Table 24.1