Other Important Tests and Procedures

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

• Describe the diagnostic values of the sputum examination, and include common organisms associated with respiratory disorders:

• Gram-negative organisms (Klebsiella, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Haemophilus influenzae, Legionella pneumophila)

• Gram-positive organisms (Streptococcus, Staphylococcus)

• Viral organisms (Mycoplasma pneumoniae, respiratory syncytial virus)

• Discuss the diagnostic values of the following tests and procedures:

• Endoscopic examinations (bronchoscopy and mediastinoscopy)

• Video-assisted thoracoscopy (VATS)

• Describe the following components of hematology testing:

• Red blood cell (RBC) count (red blood cell indices and types of anemias)

• White blood cell (WBC) count, including granular leukocytes and nongranular leukocytes

• Describe the role of platelets, including the following:

• Causes of platelet deficiency

• Clinical significance of platelet deficiency

• Identify the following blood chemistry tests commonly monitored in respiratory care:

• Serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (SGOT)

• Aspartate aminotransferase (AST)

• Alanine aminotransferase (ALT)

• Identify the following electrolytes commonly monitored in respiratory care:

• Define key terms and complete self-assessment questions at the end of the chapter and on Evolve.

Sputum Examination

A sputum sample can be obtained by expectoration, tracheal suction, or bronchoscopy (discussed later). In addition to the analysis of the amount, quality, and color of the sputum (previously discussed in Chapter 2, page 44), the sputum sample may be examined for (1) culture and sensitivity, (2) Gram stain, (3) acid-fast smear and culture, and (4) cytology.

For a culture and sensitivity study, a single sputum sample is collected in a sterile container. This test is performed to diagnose bacterial infection, select an antibiotic, and evaluate the effectiveness of antibiotic therapy. The turnaround time for this test is 48 to 72 hours. The Gram staining of sputum is performed to classify bacteria into gram-negative organisms and gram-positive organisms. The results of the Gram stain tests guide therapy until the culture and sensitivity results are obtained. Box 8-1 presents common organisms associated with respiratory disorders. All but the viral organisms can be seen on a Gram stain.

Endoscopic Examinations

Bronchoscopy

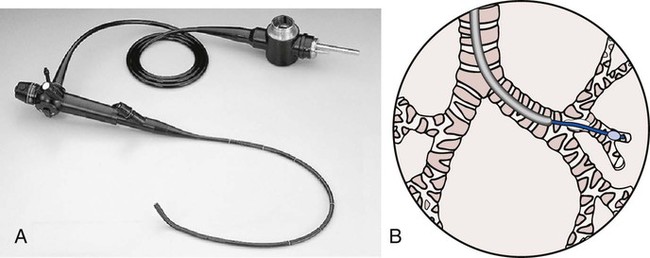

A bronchoscopy is a well-established diagnostic and therapeutic tool used by a number of medical specialists, including those in intensive care units, special procedure rooms, and outpatient settings. With minimal risk to the patient—and without interrupting the patient’s ventilation—the flexible fiberoptic bronchoscope allows direct visualization of the upper airways (nose, oral cavity, and pharynx), larynx, vocal cords, subglottic area, trachea, bronchi, lobar bronchi, and segmental bronchi down to the third or fourth generation. Under fluoroscopic control, more peripheral areas can be examined or treated (Figure 8-1). Bronchoscopy may be diagnostic or therapeutic.

Therapeutic bronchoscopy includes (1) suctioning of excessive secretions or mucous plugs, especially when lung atelectasis is forming, (2) the removal of foreign bodies or cancer obstructing the airway, (3) selective lavage (with normal saline or mucolytic agents), and (4) management of life-threatening hemoptysis. Although the virtues of therapeutic bronchoscopy are well established, routine respiratory therapy modalities at the patient’s bedside (e.g., chest physical therapy, intermittent percussive ventilation [IPV], postural drainage, deep breathing and coughing techniques, and positive expiratory pressure [PEP] therapy) are considered the first line of defense in the treatment of atelectasis from pooled secretions. Clinically, therapeutic bronchoscopy is commonly used in the management of bronchiectasis, lung abscess, smoke inhalation and thermal injuries, and lung cancer (see Bronchopulmonary Hygiene Therapy Protocol 9-2, page 120).

Lung Biopsy

A lung biopsy sample can be obtained by means of a transbronchial needle biopsy or an open-lung biopsy. A transbronchial lung biopsy entails passing a forceps or needle through a bronchoscope to obtain a specimen (Figure 8-2). An open lung biopsy involves surgery to remove a sample of lung tissue. An incision is made over the area of the lung from which the tissue sample is to be collected. In some cases a large incision may be necessary to reach the suspected problem area. After the procedure a chest tube is inserted for drainage and suction for 7 to 14 days. An open-lung biopsy is usually performed when either a bronchoscopic biopsy or a needle biopsy has been unsuccessful or cannot be performed or when a larger piece of tissue is necessary to establish a diagnosis.

Thoracentesis

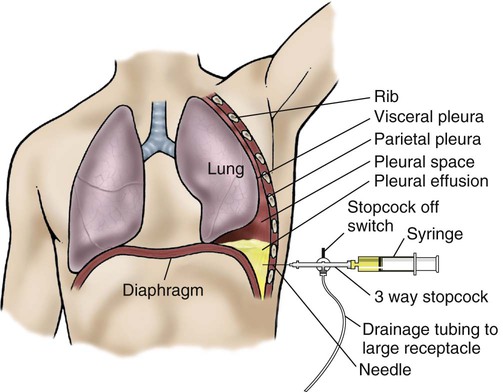

Thoracentesis (also called thoracocentesis) is a procedure in which excess fluid accumulation (pleural effusion) between the chest cavity and lungs (pleural space) is aspirated through a needle inserted through the chest wall (Figure 8-3). A chest radiograph, CT scan, or ultrasound scan may be used to confirm the precise location of the fluid. Once the fluid has been located, thoracentesis may be performed for diagnostic or therapeutic purposes.

Pleurodesis

Complications may be specific for each sclerosant.

• Talc and doxycycline can cause fever and pain.

• Quinacrine can cause low blood pressure, fever, and hallucination.

Pleurodesis may fail because of the following complications:

Hematology, Blood Chemistry, and Electrolyte Findings

Hematology

Red Blood Cell Count

The RBCs (erythrocytes) constitute the major portion of the blood cells. The healthy man has about 5 million RBCs in each cubic millimeter (mm3) of blood. The healthy woman has about 4 million RBCs in each cubic millimeter of blood. Clinically, the total number of RBCs and the RBC indices are useful in assessing the patient’s overall oxygen-carrying capacity. The RBC indices are helpful in the identification of specific RBC deficiencies. Table 8-1 provides an overview of the red blood cell indices and types of anemias.

Table 8-1

| Index | Description |

| Hematocrit (Hct) | The Hct is the volume of red blood cells (RBCs) in 100 mL of blood and is expressed as a percentage of the total volume. In the healthy man the Hct is about 45%; in the healthy woman the Hct is about 42%. In the healthy newborn the Hct ranges from 45% to 60%. The Hct also is called the packed cell volume (PCV). |

| Hemoglobin (Hb) | Most of the oxygen that diffuses into the pulmonary capillary blood rapidly moves into the RBCs and chemically attaches to the Hb. Each RBC contains approximately 280 million Hb molecules. The Hb value is reported in grams per 100 mL of blood (also referred to as grams percent of hemoglobin [g% Hb]). The normal Hb value for men is 14 to 16 g%. The normal Hb value for women is 12 to 15 g%. Hb constitutes about 33% of the RBC weight. |

| Mean cell volume (MCV) | The MCV is the actual size of the RBCs and is used to classify anemias. It is an index that expresses the volume of a single red cell and is measured in cubic microns. The normal MCV is 87 to 103 cubic microns for both men and women. |

| Mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC) | The MCHC is a measure of the concentration or proportion of Hb in an average (mean) RBC. The MCHC is derived by dividing the g% Hb by the Hct. For example, if a patient has 15 g% Hb and an Hct of 45%, the MCHC is 33%. The normal MCHC for men and women ranges from 32% to 36%. The MCHC is most useful in assessing the degree of anemia because the two most accurate hematologic measurements (Hb and Hct—not RBC) are used for the test. |

| Mean cell hemoglobin (MCH) | The MCH is a measure of weight of Hb in a single RBC. This value is derived by dividing the total Hb (g% Hb) by the RBC count. The MCH is useful in diagnosing severely anemic patients but not as good as the MCHC because the RBC is not always accurate. The normal range for the MCH is 27 to 32 picograms per RBC. |

| Types of Anemias | |

| Normochromic (normal Hb) and normocytic (normal cell size) anemia | Normochromic anemia is most commonly caused by excessive blood loss. The amount of Hb and the number of RBCs are decreased, but the individual size and content remain normal. Clinically, the laboratory report reveals the following: |

White Blood Cell Count

The major functions of the white blood cell count (WBCs) (leukocytes) are to (1) fight against infection, (2) defend the body by phagocytosis against foreign substances, and (3) produce (or at least transport and distribute) antibodies in the immune response. The WBCs are far less numerous than the RBCs, averaging 5000 to 10,000 cells per cubic millimeter of blood. There are two types of WBCs: granular leukocytes and nongranular leukocytes. Because the general function of the leukocytes is to combat inflammation and infection, the clinical diagnosis of an injury or infection often entails a differential count, which is the determination of the number of each type of cell in 100 WBCs. Box 8-2 shows a normal differential count. Table 8-2 provides an overview of cell types and common causes for their increase (leukocytosis).

Table 8-2

| Cell Type | Causes of Increase |

| Neutrophil | Bacterial infection, inflammation |

| Eosinophil | Allergic reaction, parasitic infection |

| Basophil | Myeloproliferative disorders |

| Monocyte | Chronic infections, malignancies |

| Lymphocyte | Viral infections |

Blood Chemistry

A basic knowledge of blood chemistry, normal values, and common health problems that alter these values is an important cornerstone of patient assessment. Table 8-3 lists the blood chemistry tests usually monitored in respiratory care.

Table 8-3

Blood Chemistry Tests Commonly Monitored in Respiratory Care

| Chemical | Normal Value | Common Abnormal Findings |

| Glucose | 70 to 110 mg/dl |

Electrolytes

For the cells of the body to function properly, a normal concentration of electrolytes must be maintained. Therefore the monitoring of the electrolytes is extremely important in the patient whose body fluids are being endogenously or exogenously manipulated (e.g., intravenous therapy, renal disease, diarrhea). Table 8-4 lists electrolytes monitored in respiratory care.

Table 8-4

Electrolytes Commonly Monitored in Respiratory Care

| Electrolyte | Normal Value | Common Abnormal Findings | Clinical Manifestations |

| Sodium (Na+) | 136 to 142 mEq/L |