Chapter 676 Osteomyelitis

Etiology

Bacteria are the most common pathogens in acute skeletal infections. In osteomyelitis, Staphylococcus aureus (Chapter 174.1) is the most common infecting organism in all age groups, including newborns. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant S. aureus (CA-MRSA) isolates account for >50% of S. aureus isolates recovered from children with osteomyelitis in some reports. The USA300 clone of S. aureus is the most common among CA-MRSA isolates in the USA and is more likely to cause venous thrombosis in children with acute osteomyelitis than other S. aureus clones or other bacteria for reasons that are not known.

Group B streptococcus (Chapter 177) and gram-negative enteric bacilli (Escherichia coli, Chapter 192) are also prominent pathogens in neonates; group A streptococcus (Chapter 176) constitutes <10% of all cases. After 6 yr of age, most cases of osteomyelitis are caused by S. aureus, streptococcus, or Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Chapter 197). Cases of Pseudomonas infection are related almost exclusively to puncture wounds of the foot, with direct inoculation of P. aeruginosa from the foam padding of the shoe into bone or cartilage, which develops as osteochondritis. Salmonella species (Chapter 190) and S. aureus are the two most common causes of osteomyelitis in children with sickle cell anemia. S. pneumoniae (Chapter 175) most commonly causes osteomyelitis in children <24 mo of age or children with sickle cell anemia. Bartonella henselae (Chapter 201.2) can cause osteomyelitis of any bone but especially in pelvic and vertebral bones.

Infection with atypical mycobacteria (Chapter 209), S. aureus, or Pseudomonas can occur after penetrating injuries. Fungal infections usually occur as part of multisystem disseminated disease; Candida (Chapter 226) osteomyelitis sometimes complicates fungemia in neonates with or without indwelling vascular catheters.

Epidemiology

The majority of osteomyelitis cases in previously healthy children are hematogenous. Minor closed trauma is a common preceding event in cases of osteomyelitis, occurring in ∼30% of patients. Infection of bones can follow penetrating injuries or open fractures. Bone infection following orthopedic surgery is uncommon. Impaired host defenses also increase the risk of skeletal infection. Other risk factors are noted in Table 676-1.

Table 676-1 MICROORGANISMS ISOLATED FROM PATIENTS WITH OSTEOMYELITIS AND THEIR CLINICAL ASSOCIATIONS

| MOST COMMON CLINICAL ASSOCIATION | MICROORGANISM |

|---|---|

| Frequent microorganism in any type of osteomyelitis | Staphylococcus aureus (susceptible or resistant to methicillin) |

| Foreign body–associated infection | Coagulase-negative staphylococci, other skin flora, atypical mycobacteria |

| Common in nosocomial infections | Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Candida spp. |

| Decubitus ulcer | S. aureus, streptococci and/or anaerobic bacteria |

| Sickle cell disease | Salmonella spp., S. aureus, or Streptococcus pneumoniae |

| Exposure to kittens | Bartonella henselae |

| Human or animal bites | Pasteurella multocida or Eikenella corrodens |

| Immunocompromised patients | Aspergillus spp., Candida albicans, or Mycobacteria spp. |

| Populations in which tuberculosis is prevalent | Mycobacterium tuberculosis |

| Populations in which these pathogens are endemic | Brucella spp., Coxiella burnetii, fungi found in specific geographic areas (coccidioidomycosis, blastomycosis, histoplasmosis) |

Modified From Lew DP, Waldvogel FA: Osteomyelitis, Lancet 364:369–379, 2004.

Clinical Manifestations

Long bones are principally involved in osteomyelitis (Table 676-2); the femur and tibia are equally affected and together constitute almost half of all cases. The bones of the upper extremities account for one fourth of all cases. Flat bones are less commonly affected.

| BONE | % |

|---|---|

| Femur | 23-28 |

| Tibia | 20-24 |

| Humerus | 5-13 |

| Radius | 5-6 |

| Phalanx | 3-5 |

| Pelvis | 4-8 |

| Calcaneus | 4-8 |

| Ulna | 4-8 |

| Metatarsal | ∼2 |

| Vertebrae | ∼2 |

| Sacrum | ∼2 |

| Clavicle | ∼2 |

| Skull | ∼1 |

| Carpal bone | <1 |

| Rib | <1 |

| Metacarpal | <1 |

| Cuboid | <1 |

| Cuneiform | <1 |

| Pyriform aperture | <1 |

| Olecranon | <1 |

| Maxilla | <1 |

| Mandible | <1 |

| Scapula | <1 |

| Sternum | <1 |

| Foot | 1 |

Modified from Gafur OA, Copley LA, Hollmig ST, et al: The impact of the current epidemiology of pediatric musculoskeletal infection on evaluation and treatment guidelines, J Pediatr Orthop 28(7):777–785, 2008.

Radiographic Evaluation

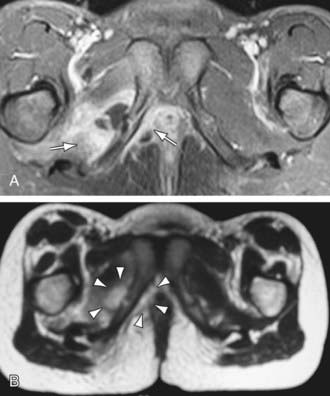

Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging

CT can demonstrate osseous and soft-tissue abnormalities and is ideal for detecting gas in soft tissues. In selected children who cannot remain still or tolerate sedation, CT is a valuable imaging modality. MRI is more sensitive than CT or radionuclide imaging in acute osteomyelitis and is the best radiographic imaging technique for identifying abscesses and for differentiating between bone and soft-tissue infection. MRI provides precise anatomic detail of subperiosteal pus and accumulation of purulent debris in the bone marrow and metaphyses for possible surgical intervention. In acute osteomyelitis, purulent debris and edema appear dark, with decreased signal intensity on T1-weighted images, with fat appearing bright (Fig. 676-1). The opposite is seen in T2-weighted images. The signal from fat can be diminished with fat-suppression techniques to enhance visualization. Gadolinium administration can also enhance MRI. Cellulitis and sinus tracts appear as areas of high signal intensity on T2-weighted images. MRI can also demonstrate a contiguous septic arthritis, pyomyositis, or venous thrombosis.

Differential Diagnosis

Appendicitis, urinary tract infection, and gynecologic disease are among the conditions in the differential diagnosis of pelvic osteomyelitis. Children with leukemia commonly have bone pain or joint pain as an early symptom. Neuroblastoma with bone involvement may be mistaken for osteomyelitis. Primary bone tumors need to be considered, but fever and other signs of illness are generally absent except in Ewing sarcoma. In patients with sickle cell disease, distinguishing bone infection from infarction may be challenging. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO) and synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteitis syndrome are rare noninfectious conditions in children characterized by recurrent osteoarticular inflammation and different skin conditions, palmoplantar pustulosis, psoriasis, severe acne, neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet syndrome, Chapter 163), and pyoderma gangrenosum.

Arnold SR, Elias D, Buckingham SC, et al. Changing patterns of acute hematogenous osteomyelitis and septic arthritis. Emergence of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Pediatr Orthop. 2006;26:703-708.

Bocchini C, Hulten KG, Mason EOJr, et al. Panton-Valentine leukodicin genes are associated with enhanced inflammatory response and local disease in acute hematogenous Staphylococcus aureus osteomyelitis in children. Pediatrics. 2006;117:433-440.

Browne LP, Mason EO, Kaplan SL, et al. Optimal imaging strategy for community-acquired Staphylococcus aureus musculoskeletal infections in children. Pediatr Radiol. 2008;38:841-847.

Chen CJ, Chiu CH, Lin TY, et al. Experience with linezolid therapy in children with osteoarticular infections. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26:985-988.

Chometon S, Benito Y, Chaker M, et al. Specific real-time polymerase chain reaction places Kingella kingae as the most common cause of osteoarticular infections in young children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26:377-381.

Connolly LP, Connolly SA, Druback LA, et al. Acute hematogenous osteomyelitis of children: assessment of skeletal scintigraphy-based diagnosis in the era of MRI. J Nucl Med. 2002;43:1310-1316.

Dubnov-Raz G, Ephros M, Garty BZ, et al. Invasive pediatric Kingella kingae infections. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29(7):639-642.

Dubnov-Raz G, Scheuerman O, Chodick G, et al. Invasive Kingella kingae infections in children: clinical and laboratory characteristics. Pediatrics. 2008;122:1305-1309.

Fernandez M, Carrol CL, Baker CJ. Discitis and vertebral osteomyelitis in children: an 18-year review. Pediatrics. 2000;105:1299-1304.

Floyed RL, Steele RW. Culture-negative osteomyelitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22:731-735.

Gafur OA, Copley LA, Hollmig ST, et al. The impact of the current epidemiology of pediatric musculoskeletal infection on evaluation and treatment guidelines. J Pediatr Orthop. 2008;28:777-785.

Gomez M, Maraqa N, Alvarez A, et al. Complications of outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy in childhood. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2001;20:541-543.

Gonzales BE, Teruya J, Mahoney DHJr, et al. Venous thrombosis associated with staphylococcal osteomyelitis in children. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1675-1679.

Gray PEA, McMullan B, Ziegler JB. Getting to the bones of the matter. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2010;95:178-182.

Hajjaji N, Hocqueloux L, Kerdraon R, et al. Bone infection in cat-scratch disease: a review of the literature. J Infect. 2007;54:417-421.

Ibia EO, Imoisili M, Pikis A. Group A β-hemolytic streptococcal osteomyelitis in children. Pediatrics. 2003;112:e22-e26.

Jacobs RF, McCarthy RE, Elser JM. Pseudomonas osteochondritis complicating puncture wounds of the foot in children: a 10-year evaluation. J Infect Dis. 1989;160:657-661.

Kaplan SL. Osteomyelitis in children. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2005;19:787-797.

Lew DP, Waldvogel FA. Osteomyelitis. Lancet. 2004;364:369-379.

López VN, Ramos JM, Meseguer V, et al. Microbiology and outcomes of iliopsoas abscess in 124 patients. Medicine. 2009;88:120-130.

Maraqa NF, Gomez MM, Rathore MH. Outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy in osteoarticular infections in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 2002;22:506-510.

Marschall J, Bhavan KP, Olsen MA, et al. The impact of prebiopsy antibiotics on pathogen recovery in hematogenous vertebral osteomyelitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;52:867-872.

Martinez-Aguilar G, Hammerman WA, Mason EOJr, et al. Clindamycin treatment of invasive infections caused by community-acquired, methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible S. aureus in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22:593-598.

Nelson JD. Bugs, drugs and bones: a pediatric infectious disease specialist reflects on management of musculoskeletal infections. J Pediatr Orthop. 1999;19:141-142.

Nguyen S, Pasquet A, Legout L, et al. Efficacy and tolerance of rifampicin-linezolid compared with rifampicin-cotrimoxazole combinations in prolonged oral therapy for bone and joint infections. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009;15:1163-1169.

Pääkkönen M, Kalio MJT, Kallio PE, et al. Sensitivity of erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein in childhood bone and joint infections. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;468:861-866.

Pannaraj PS, Hulten KG, Gonzalez BE, et al. Infective pyomyositis and myositis in children in the era of community-acquired, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:953-960.

Peltola H, Paakkonen M, Kallio P, et al. Short- versus long-term antimicrobial treatment for acute hematogenous osteomyelitis of childhood. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29(12):1123-1128.

Saavedra-Lozano J, Mejías A, Ahmed N, et al. Changing trends in acute osteomyelitis in children: impact of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections. J Pediatr Orthop. 2008;28:569-575.

Saigal G, Azouz EM, Abdenour G. Imaging of osteomyelitis with special reference to children. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol. 2004;8:255-265.

Shih HN, Shih LY, Wong YC. Diagnosis and treatment of subacute osteomyelitis. J Trauma. 2005;58:83-87.

Verdier I, Gayet-Ageron A, Ploton C, et al. Contribution of a broad range polymerase chain reaction to the diagnosis of osteoarticular infections caused by Kingella kingae. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24:692-696.

Weber-Chrysochoou C, Corti N, Goetschel P, et al. Pelvic osteomyelitis: a diagnostic challenge in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42:553-557.

Yagupsky P. K. kingae infections of the skeletal system in children: diagnosis and therapy. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2004;2:787-794.

Yagupsky P. Kingella kingae: from medical rarity to an emerging paediatric pathogen. Lancet Infect Dis. 2004;4:358-367.

Yagupsky P, Porsch E, St Geme JW3rd. Kingella kingae: an emerging pathogen in young children. Pediatrics. 2011;127(3):557-565.

Zaoutis T, Localio AR, Leckerman K, et al. Prolonged intravenous therapy versus early transition to oral antimicrobial therapy for acute osteomyelitis in children. Pediatrics. 2009;123:636-642.