Chapter 7 Osteochondral Allografts

Background and Rationale

The fundamental concept governing fresh osteochondral allografting is the transplantation of architecturally mature hyaline cartilage, with living chondrocytes that survive transplantation and are thus capable of supporting the cartilage matrix.1

The transplantation of mature hyaline cartilage obviates the need to rely on techniques that induce cells to form cartilage tissue, which are central to other restorative procedures

Indications

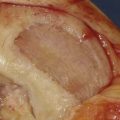

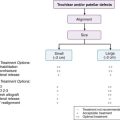

Many proposed treatment algorithms suggest the use of allografts for large lesions (>2 or 3 cm) or for salvage in difficult reconstructive situations. In our experience, allografts can be considered as a primary treatment option for osteochondral lesions >2 cm in diameter, as is typically seen in osteochondritis dissecans and osteonecrosis (Fig. 7-1).

Graft Sizing

The surgical technique for fresh osteochondral allografting depends on the joint and surface to be grafted. Common to all fresh allografting procedures is matching the donor with recipient.2,3. This is done on the basis of size.

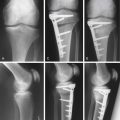

In the knee, an anteroposterior (AP) radiograph with a magnification marker is used, and a measurement of the medial-lateral dimension of the tibia is made and corrected for magnification. Some surgeons may prefer to use measurements based on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) images, but we have not found this to be more useful than plain radiographs.

Decision Making for Dowel or Shell Technique

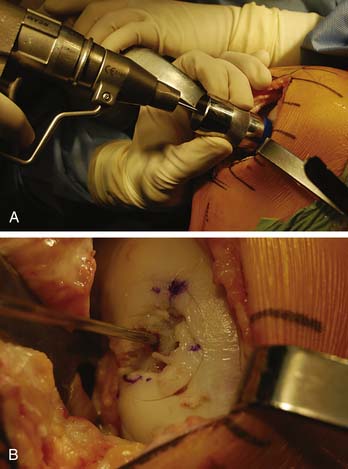

The press-fit plug technique is a similar in principle to autologous osteochondral transfer (OATS). A number of commercially available instruments are available (Fig. 7-2).

Shell grafts are technically more difficult to perform and typically require fixation. However, depending on the technique employed, less normal cartilage may need to be sacrificed.

Surgical Approach

Extending the arthrotomy proximal or distal may be necessary to mobilize the extensor mechanism.

The knee is then flexed or extended until the proper degree of flexion is noted that presents the lesion into the arthrotomy site (Fig. 7-3).

Lesion Inspection and Preparation

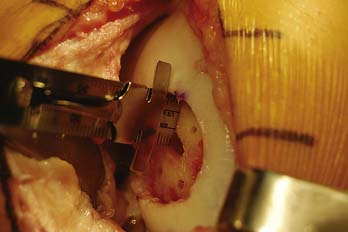

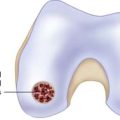

The lesion is inspected and palpated with a probe to determine the extent, margins, and maximum size. The size of the proposed graft is then determined, utilizing sizing dowels (Fig. 7-4). If the lesion falls between two sizes it is generally preferred to start with the smaller size. At this point the surgeon should also determine if the allograft tissue is adequate in dimension (usually diameter) to harvest the proposed allograft plug (this becomes critical in grafts 25 mm or greater).

A guide wire is driven through the sizing dowel into the center of the lesion, perpendicular to the curvature of the articular surface (Fig. 7-5 A-B).

The cartilage surface is scored, and a special reamer is used to remove the remaining articular cartilage and 3 to 4 mm of subchondral bone (Fig. 7-6).

The reamings should be retained to be used as bone graft if needed. Bone grafting is performed to fill any deeper or more extensive osseous defects or to modify the fit of the graft if there is a depth mismatch between the recipient socket and allograft plug. At this point the guide pin can be removed and depth measurements are made and recorded in the four quadrants of the prepared recipient site (Fig. 7-7).

Graft Preparation

The corresponding anatomical location of the recipient site then is identified on the graft (Fig. 7-8). The graft is placed into a graft holder (or alternately, held with bone-holding forceps). A saw guide then is placed in the appropriate position, again perpendicular to the articular surface, exactly matching the orientation used to create the recipient site.

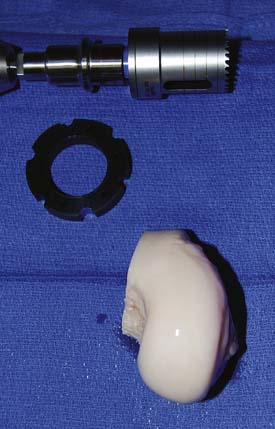

The appropriate size matched coring saw is used to core out the graft (Fig. 7-9). The graft can be cut from the donor condyle and removed as a long plug. The allograft plug thickness now must be adjusted. Depth measurements, which were taken from the recipient, are transferred to the graft (Fig. 7-10).

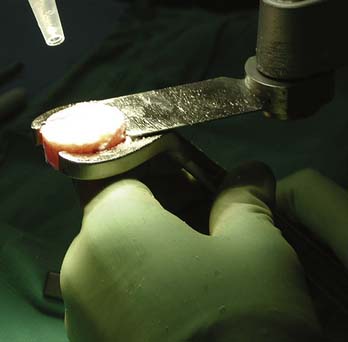

The graft is mounted on the graft holder, which serves as a cutting guide and cut with an oscillating saw (Fig 7-11). Often, this must be done multiple times, to ensure precise thickness, matching the prepared defect in the patient (Fig. 7-12). It is also helpful at this time to bevel the edge of the osseous portion of the graft with a small rongeur or rasp to facilitate initial fitting into the recipient socket. The graft should be irrigated copiously with a high-pressure lavage to remove all marrow elements (Fig. 7-13).

FIGURE 7-11 The graft is mounted on the graft holder and excess bone is removed with the oscillating saw.

Graft Insertion

The graft is then inserted by hand in the appropriate rotation and is gently pressed into place manually (Fig. 7-14). To fully seat the graft, the joint can be carefully brought through a range of motion, allowing the opposing articular surface to seat the graft (Fig. 7-15). Finally, gentle tamping can be performed to fully seat the graft. Excessive and forceful striking of the graft should be avoided, as this leads to chondrocyte necrosis.

Once the graft is seated, a determination is made whether additional fixation is required (Fig. 7-16). Typically, absorbable pins are utilized, particularly if the graft is large or has an exposed edge.

Shell Allograft Technique

The graft and host bed are then copiously irrigated, and the graft placed flush with the articular surface. The need for fixation is based on the degree of inherent stability.

Results with Osteochondral Allografts

Garrett4 first reported on 17 patients treated with fresh osteochondral allografts for OCD of the lateral femoral condyle utilizing a dowel technique. All patients had failed previous surgery, and in a 2-to-9-year follow-up period, 16 out of 17 patients were reported as asymptomatic.

Emmerson et al.5 reported our experience in the treatment of osteochondritis dissecans of the medial and lateral femoral condyle. We evaluated 69 knees in 66 patients at a mean of 5.2 years postoperatively. All allografts were implanted within 5 days of procurement. In all, 49 males and 17 females, with a mean age of 28 years (range 15 to 54) underwent allografting using either the dowel or shell technique. Forty lesions involved the medial femoral condyle and 29 the lateral femoral condyle. An average of 1.6 surgeries had been performed on the knee before the allograft procedure. Allograft size was highly variable, with a range of 1 to 13 cm2. The average allograft size was 7.4 cm2. Overall, 53/67 (79%) knees were rated good or excellent, 10/67 (15%) were rated fair, and 6/67 (6%) were rated poor. Six patients had reoperations on the allograft: one was converted to total knee arthroplasty, and five underwent revision allografting at 1, 2, 5, 7, and 8 years after the initial allograft. Forty-nine out of 66 patients completed questionnaires: 96% reported satisfaction with their treatment; 86% reported less pain. Subjective knee function improved from a mean of 3.5 to 7.9 on a 10-point scale.

Chu6 reported on 55 consecutive knees undergoing osteochondral allografting. This group included patients with diagnoses such as traumatic chondral injury, avascular necrosis, osteochondritis dissecans, and patellofemoral disease. The mean age of this group was 35.6 years, with follow-up averaging 75 months (range 11 to 147 months). Of the 55 knees, 43 were unipolar replacements and 12 were bipolar resurfacing replacements. In this mixed patient population, 42/55 (76%) of these knees were rated good to excellent, and 3/55 were rated fair, for an overall success rate of 82%. It is important to note that 84% of the knees that underwent unipolar femoral grafts were rated good to excellent, and only 50% of the knees with bipolar grafts achieved good or excellent status.

Aubin7 reported on the Toronto experience with fresh osteochondral allografts of the femoral condyle. Sixty knees were reviewed, with a mean follow-up of 10 years (range 58 to 259 months). The etiology of the osteochondral lesion was trauma in 36, osteochondritis in 17, osteonecrosis in 6, and arthrosis in 1. Realignment osteotomy was performed in 41 patients and meniscal transplantation in 17. Twelve knees required graft removal or conversion to total knee arthroplasty. The remaining 48 patients averaged a Hospital for Special Surgery Score of 83 points. The authors reported 85% graft survivorship at 10 years.

Williams8 reported on the outcome of 19 fresh, hypothermically stored allografts, with a mean time to implantation from graft recovery of 30 days. At minimum 2-year follow-up, all patients showed functional improvement and magnetic resonance imaging demonstrated normal cartilage signal in 18 of 19 grafts and complete or partial osseous incorporation in 14 grafts.

McCulloch9 reported on a series of 25 fresh, stored osteochondral allografts of the femoral condyle. Statistically significant improvements were seen in all outcome measures, and 22 of 25 were radiographically incorporated into host bone.

LaPrade10 reported on 23 patients treated with osteochondral allografts for focal femoral condyle lesions. At a mean follow-up of 3 years, 22 of 23 grafts were stable and incorporated. Cincinnati and the International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) scores demonstrated significant improvement in this cohort.

1. Czitrom A.A., Keating S., Gross A.E. The viability of articular cartilage in fresh osteochondral allografts after clinical transplantation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72:574-581.

2. Görtz S., Bugbee W.D. Fresh osteochondral allografts: graft processing and clinical applications. J Knee Surg. 2006;19:231-240.

3. Görtz S., Bugbee W.D. Allografts in articular cartilage repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:1374-1384.

4. Garrett J.C. Fresh osteochondral allografts for treatment of articular defects in osteochondritis dissecans of the lateral femoral condyle in adults. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;303:33-37.

5. Emmerson B.C., Görtz S., Bugbee W.D., et al. Fresh osteochondral allografting in the treatment of osteochondritis dissecans of the femoral condyle. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:907-914.

6. Chu C.R., Convery F.R., Akeson W.H., et al. Articular cartilage transplantation. Clinical results in the knee. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;360:159-168.

7. Aubin P.P., Cheah H.K., Davis A.M., et al. Long-term follow-up of fresh femoral osteochondral allografts for posttraumatic knee defects. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;1(suppl 39):S318-S327.

8. Williams R.J.3rd, Ranawat A.S., Potter H.G., et al. Fresh stored allografts for the treatment of osteochondral defects of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:718-726.

9. McCulloch P.C., Kang R.W., Sobhy M.H., et al. Prospective evaluation of prolonged fresh osteochondral allograft transplantation of the femoral condyle: minimum 2-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(3):411-420.

10. LaPrade R.F., Botker J., Herzog M., et al. Refrigerated osteoarticular allografts to treat articular cartilage defects of the femoral condyles. A prospective outcomes study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:805-811.

1. Görtz S., Bugbee W.D. Allografts in articular cartilage repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(6):1374-1384.

2. Bonner K.F., Bugbee W.D. Osteochondral Allografting in the Knee. In: Cole B., Malek M., editors. Textbook of Arthroscopy. St. Louis: Saunders; 2004:611-623.

3. Bugbee W.D. Osteochondral Allograft Transplantation. In: Cole B., Malek M., editors. Articular Cartilage Lesions: A Practical Guide toward Assessment and Treatment. New York: Springer-Verlag, 2004. 82–A94

4. Bugbee W.D. Allograft Osteochondral Plugs. In: Jackson D.W., editor. Master Techniques in Orthopaedic Surgery: Reconstructive Knee Surgery. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2008. 475–A83