Chapter 16. Osteoarthritis

Pathology

Osteoarthritis is a poor name for degenerative joint disease. Articular cartilage is involved more than bone, and inflammation is secondary to the disease and not the cause. ‘Osteoarthrosis’ is often used as an alternative and ‘osteochondrosis’ would be more accurate, but ‘osteoarthritis’ is so well established that it is unlikely to be displaced.

Osteoarthritis is the result of progressive breakdown of the joint surface and can follow any insult to any joint. Infection, direct or indirect trauma to the articular cartilage and joint diseases can all lead to osteoarthritis. The disease involves mainly the large weight-bearing joints. In this respect it differs from rheumatoid arthritis, which involves the synovium of many joints and is commoner in the small joints of the hands and feet (Fig. 16.1).

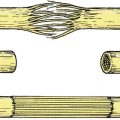

|

| Fig. 16.1

Some differences between rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis mainly affects the weight-bearing joints and is more common in elderly and heavyweight people. Rheumatoid arthritis affects small joints, is symmetrical and is commonest in young women.

|

Primary osteoarthritis includes several different conditions, the commonest of which is generalized nodal osteoarthritis. White women are most often affected, during the fifth and sixth decades, by polyarticular involvement of many joints. The onset can be relatively sudden with hot, inflamed, distal interphalangeal joints.

Hip disease behaves differently. The condition is more common in men, is often unilateral with no other joint involvement and may have no obvious precipitating cause.

Secondary osteoarthritis has many causes, of which the commonest are:

1. Obesity.

2. Abnormal contour of the articular surfaces, particularly malunited fractures.

3. Malalignment of the joints from deformity, fracture or the distortion of the anatomy by previous surgery, particularly meniscectomy at the knee.

4. Joint instability due to trauma or generalized ligamentous laxity.

5. Genetic or developmental abnormalities, such as epiphyseal dysplasia, Perthes disease or slipped epiphysis.

6. Metabolic or endocrine disease, including ochronosis (alkaptonuria), acromegaly and the mucopolysaccharidoses.

8. Osteonecrosis.

9. The neuropathies, especially denervated joints and Charcot’s disease.

In short, any joint disease can cause osteoarthritis!

The development of osteoarthrosis can be considered in five stages:

1. Breakdown of articular surface.

2. Synovial irritation.

3. Remodelling.

4. Eburnation of bone and cyst formation.

5. Disorganization.

Breakdown of articular surface

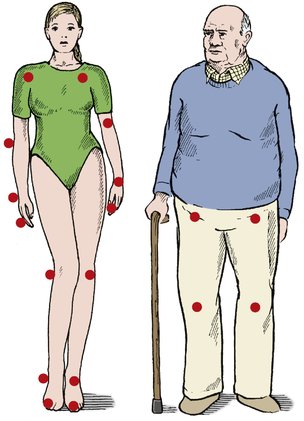

Degenerative osteoarthritis begins with failure of the articular surface (Fig. 16.2). The normal smooth surface of articular cartilage is breached, the arcades of collagen fibres break and the surface becomes rough, like a shaggy carpet. Friction against the rough surface generates particles of articular cartilage that are shed into the joint and absorbed by the synovium, where they cause an inflammatory response which the patient feels as stiffness or aching in the joint after exercise rather than at the time of use.

|

| Fig. 16.2

The development of osteoarthritis: (a) breakdown of the articular surface with rupture of the collagen arcades; (b) exposed bone with eburnation; (c) deformity and collapse.

|

Synovial irritation

The irritation of the synovium is probably due to the release of intracellular enzymes, including lysozymes, which produce hyperaemia and a cellular response in the synovial layers. The synovium can also produce degradative enzymes and mediators such as interleukin-1, which may influence chondrocyte activity. Other potential causes of damage include free radicals and the deposition of immune complexes.

Remodelling

Limited cartilage repair can occur. Superficial lesions of articular cartilage show little healing but deep lesions that penetrate cortical bone allow the influx of marrow cells and the formation of fibrocartilage. Hyaline cartilage, however, is a once-in-a-lifetime tissue and does not regenerate.

The subchondral bone is also abnormally active, with an increase in both the density of the tissue and the number of cells. At the margin of the joint, new bone forms as osteophytes covered by fibrocartilage, perhaps induced by wear particles swept to the edge of the joint by joint movement. There, the osteophytes restrict joint movement.

A line of dense, hard, resilient bone forms just below the cartilage and the joint ‘remodels’ so that there is a change in shape and congruity. This alters the pattern of weight-bearing, which in turn means that the load is taken by different areas of articular cartilage.

Eburnation of bone and cyst formation

If the joint is rested, the wear particles are gradually absorbed. Fibrous tissue may form in the defect on the joint surface but as time goes by this repair process gradually fails and the articular surface is eroded to expose subchondral bone, which subsequently becomes polished and eburnated.

Raw bone rubbing against raw bone is painful. The eburnated bone is not as slippery as healthy articular cartilage, friction across the joint is increased and weight transmission across the joint becomes uneven. This change overloads some parts of the joint surface and microfractures occur in the trabeculae of the cancellous bone.

The microfractures heal with callus, which increases the rigidity of the bone so that the bone gradually becomes denser, more sclerotic and less resilient. This, in turn, causes more microfractures and the normal architecture of the bone is lost.

At this stage, synovial fluid enters the cancellous bone under pressure through cracks in the articular surface, producing cavities that are seen radiologically as ‘cysts’. These cysts fill with fibrous tissue and become lined with a thin shell of cortical bone.

Disorganization

As the disease advances, the joint becomes progressively stiffer and more deformed as the osteophytes enlarge and the bone surfaces are worn away. The ball and socket of the hip is gradually converted into a roller bearing and hinge joints develop a valgus or varus deformity as one side is worn away.

As bone is lost the ligaments become looser, not because they lengthen but because the bones that they support become shorter.

Radiological appearance

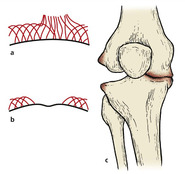

The radiological appearance of osteoarthritis reflects these pathological changes (Fig. 16.3). The joint spaces narrow, the weight-bearing surface becomes sclerotic, osteophytes form around the joint margins and cysts are seen in the subchondral bone. The shape of the bone slowly alters and this deformity can be seen radiologically as well as clinically (Fig. 16.4).

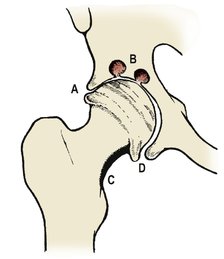

|

| Fig. 16.3

Radiological appearances of osteoarthritis: ( A) narrowing of the joint space; ( B) cysts; ( C) sclerosis; ( D) osteophytes.

|

|

| Fig. 16.4

Radiograph of a hip with osteoarthritis.

|

Clinical presentation

The symptoms of osteoarthritis vary from joint to joint but there are three principal features:

1. Pain.

2. Loss of movement.

3. Altered function.

Pain

Pain is worse when the joint is under load and is greatest in the weight-bearing joints of the lower limb. Wear particles cause synovitis after the exercise has ceased. The weekend golfer may experience no pain during the game but will find that the joints are stiff after rest and painful after activity in the early part of the following week.

Loss of movement

Movement is lost as osteophytes form and the joint changes shape. This occurs so slowly that few patients notice any sudden change.

Altered function

Alterations of joint function occur imperceptibly. Without being aware of it, patients may subconsciously restrict their activities to those that the joints permit. They may choose not to walk as far as they once did, or not to work for as long or as hard without a pause. These limitations gradually increase.

Upper and lower limb osteoarthritis

The progress of osteoarthrosis is different in weight-bearing and non-weight-bearing joints. Weight-bearing joints in the lower limb are subjected to greater load and are more painful than those of the upper limb. Deformities are more apparent and restriction of function is severe.

In contrast, osteoarthritis of the upper limb causes little pain because the joints are seldom under load, but the shape of the joints is unsightly and loss of movement may be disabling.

These differences are important in selecting management. In the lower limb the aim is a joint that will take load without causing pain. Restoration of movement is more important in the upper limbs.

Treatment

Any condition can be treated conservatively or operatively. Osteoarthritis is no exception.

Conservative treatment

Conservative treatment includes the following measures:

1. Explanation of the condition and reassurance.

2. Advice to keep active but modify activities to avoid those things that hurt or aggravate the problem or overload the joint. If it hurts, don’t do it.

3. A walking stick and aids in the home.

4. Physiotherapy to maintain muscle bulk and joint movement.

5. Drugs, especially intermittent analgesics and NSAIDs.

6. Very occasional intra-articular steroid injections.

Explanation is important

When patients learn that they have ‘arthritis’, they see wheelchairs. It is essential to dispel this misconception and adopt a positive approach. Osteoarthritis is not a ‘disease’ like rheumatoid arthritis; it is simply a patch of fair wear and tear that will probably get very slowly worse over many years and cause some limitation of activity. Widespread and severe osteoarthritis can be disabling but this is fairly uncommon.

Modification of activity

If patients only experience pain during a certain activity they may be able to modify activities to avoid the one that hurts. If a patient with osteoarthritis of the elbow only has pain when clipping the hedge, for example, the simplest solution might be to cut down the hedge or buy an electric hedge-clipper. Similarly, patients with osteoarthritis of the hip who can walk only a few yards are able to cycle for long distances without pain, and a bicycle can solve many of their problems.

These are commonsense solutions that many patients will find without consulting their doctor but they should always be considered before advising operation.

Appliances and aids

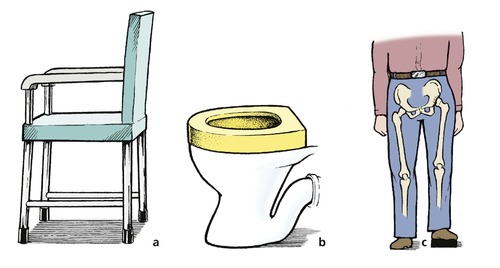

Aids such as sticks, elbow crutches or a walking frame are helpful to patients with osteoarthritis of the lower limbs. A tall chair is better for patients who lack full flexion of the hips and the knees, both of which are necessary to sit in a comfortable or ‘easy’ chair. The same patients are also helped by a high seat when using the lavatory (Fig. 16.5).

|

| Fig. 16.5

Aids for osteoarthritis of the hip: (a) firm chair with arm supports; (b) a high seat to avoid excessive flexion of the hip; (c) raise the shoe to correct shortening.

|

Osteoarthritis of the knee or hip can produce real or apparent shortening of the limb. A raise to the heel and sole of the shoe on the shorter side will make good this shortening. Although it will not alter the progress of the disease, the raise will improve the gait and take the strain off other joints and the lumbar spine.

Physiotherapy

Heat treatment by ice, infrared lamps or short-wave diathermy will often produce relief for many months.

Exercises to increase the power of muscles around osteoarthritic joints are of limited value. It is not possible to ‘compensate’ for worn joints by increasing the strength of the muscles that operate them, any more than it is possible to improve the bodywork of a rusty car by putting in a more powerful engine. It is, however, useful to increase the range of movement in degenerate joints and prevent contractures. Many patients understandably avoid moving their painful joints and function deteriorates; the more painful the joints, the less they are moved, the stiffer they become, the less they are moved, and so on. If the joints are put through their full range of movement every day, function is maintained and stiffness avoided.

Drugs

Both analgesics and anti-inflammatory drugs are available but many drugs act in both ways.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. NSAIDs include fenamate derivatives such as flurbiprofen, ibuprofen, naproxen and mefenamic acid. These drugs are prostaglandin inhibitors and reduce the inflammatory response of the synovium to articular cartilage debris. Aspirin is also a prostaglandin inhibitor as well as an analgesic and should not be underestimated.

These drugs do not abolish pain but they reduce it effectively. They do not affect the articular surfaces but the response of the synovium to wear particles of articular cartilage is reduced. Some patients learn to take their anti-inflammatory drugs before physical activity; the weekend golfer may take tablets on Saturday morning to reduce the inflammatory response that will be felt on Sunday and Monday.

Almost all NSAIDs cause gastrointestinal problems and should be taken either with food or with milk and biscuits. This gastrointestinal irritation is partly a systemic phenomenon and cannot be avoided by giving the drug parenterally or by suppository, although this can lessen the problem. In the elderly, NSAIDs may cause confusion.

NSAIDs can depress chondrocyte activity and this may cause the disease to progress more rapidly, especially in weight-bearing joints such as the hip. Because of this, NSAIDs should be given intermittently and cautiously, with courses during exacerbations and at important times for the patient, such as golf tournaments.

Analgesics. Simple analgesics such as paracetamol or dihydrocodeine have an analgesic effect only, but reduce the pain caused by raw bone rubbing on raw bone. They do not reduce the synovitis of osteoarthritis. Comparative studies suggest that NSAIDs are more effective than simple analgesics, but in practice the best results may be achieved by a combination of paracetamol with an NSAID.

In some patients with severe osteoarthritis, pain interferes with sleep and the plight of these patients is made worse by perpetual tiredness. Analgesics or anti-inflammatory drugs taken at bedtime, perhaps with a mild hypnotic, can be helpful.

Steroid injections are helpful for areas of extra-articular inflammation, particularly along joint margins or over osteophytes, but intra-articular injections are less effective. The steroid can reduce the intra-articular inflammation but the results are transient and leave the underlying pathology unchanged. Intra-articular steroids are given more often by rheumatologists than surgeons.

Operative treatment

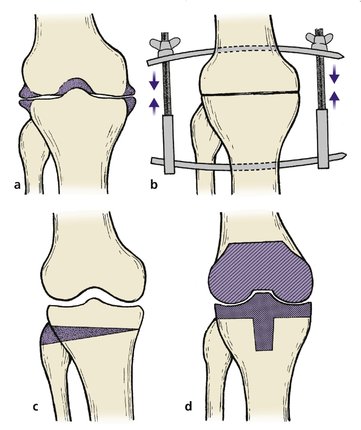

Operative treatment should only be considered if conservative measures have failed. The operations can be divided into four groups (Fig. 16.6), described below:

1. Debridement.

2. Arthrodesis.

3. Osteotomy.

4. Arthroplasty.

|

| Fig. 16.6

Operations for osteoarthritis: (a) debridement and removal of osteophytes; (b) arthrodesis; (c) osteotomy to correct alignment; (d) total joint replacement.

|

Debridement

Osteophytes are the most obvious radiological abnormality and it is tempting to remove them in the hope that the radiological appearance, and thus the patient, will be restored to normal. Although the osteophytes can be removed, they quickly recur and the benefit from this procedure is transient.

If the osteophytes seriously obstruct joint movement it is reasonable to excise them. Excision of the osteophytes also improves the appearance, which can be important in the hand where the osteophytes around the distal interphalangeal joints may be very unsightly.

Arthrodesis

Arthrodesis, the fusion of a joint, is one of the oldest operations in orthopaedic surgery and converts a stiff painful joint in bad position into a stiff, painless joint in good position. This is a fair exchange.

Arthrodesis is useful for small joints in the hand, fingers and toes, where the loss of movement in one joint can be disguised by the movement of others. In larger joints the operation has more far-reaching effects. An arthrodesed knee, for example, is good for walking but will not bend when the patient sits down, and creates particular problems when getting out of a car or using a lavatory.

Accordingly, arthrodesis is best suited to degenerative disease affecting a single joint surrounded by joints that are healthy and likely to stay healthy. It is contraindicated in diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis where many joints are involved.

If arthrodesis is carried out, the joint should be fixed in the position of function; i.e. the most useful position. To be sure that the patient will be pleased with the result it is advisable to apply a cast in the proposed position before operation, so that they can use the limb as if it were arthrodesed and assess the likely benefits for themselves.

Osteotomy

Osteotomy helps osteoarthritic joints in three ways:

1. Correcting the deformity.

2. Altering the architecture at the site of healing.

3. Dividing intraosseous vessels.

Correcting the deformity reduces the abnormal loads across the joints. This is important in the weight-bearing joints of the lower limb, where the hip, knee and ankle should be one above the other in the same vertical line. Correction of the line of weight-bearing does not ‘cure’ osteoarthritis but can slow the deterioration.

Altering the bone architecture. Cutting across the bone allows some remodelling to occur at the fracture site.

Dividing vessels. Osteotomy divides the medullary cavity of the bone, including the venous channels, and this may have some effect on pain.

Disadvantages of osteotomy. The operation causes considerable discomfort, requires a long period of rehabilitation, and the symptoms can recur. In its favour, the operation does not destroy the joint irreparably, as does an arthrodesis or an arthroplasty, and a second operation is always possible.

Arthroplasty

Arthroplasty means the creation of a joint; several types are available.

Types of arthroplasty

1. Excision arthroplasty.

2. Interposition arthroplasty.

3. Mould arthroplasty.

4. Replacement arthroplasty, including hemiarthroplasty and total replacement.

Excision arthroplasty replaces the normal joint with a fibrous ankylosis with less movement and less stability than a normal joint. Excision arthroplasty is therefore unsuitable for weight-bearing joints, but is effective in those that do not bear weight, e.g. the toe.

Disadvantages are that pain can arise in the new ‘joint’ from bone-to-bone contact across the pseudarthrosis and the instability can be distressing to the patient. The advantages are that no foreign material is inserted and the complications of infection and loosening are reduced.

Interposition arthroplasty. The formation of a pseudarthrosis can be encouraged by placing something between the bone ends. Skin, fascia and muscle have all been used but the results are little different from a straightforward excision arthroplasty.

An inert spacer, such as Silastic, can also be used as an interposition material. The results are better but the wear particles of the material can be an irritant and the joint is still unstable.

Mould arthroplasty. A hard material, such as metal, placed between the bone ends can act as a mould to shape a new joint. The idea is simple in principle but in practice the joints become stiff and the bone inside the mould can undergo aseptic necrosis. Cup arthroplasty of the hip was a good example but has now been replaced by total hip replacement.

Replacement arthroplasty. If the worn joint surfaces are removed and replaced by a prosthesis, a stable and painless joint resembling the original can be created. Two types of replacement arthroplasty are in current use:

1. Hemiarthroplasty. If only one joint surface is replaced the early results are good but the prosthetic material is likely to wear away the opposite joint surface.

Hemiarthroplasty is useful in femoral neck fractures, which almost invariably occur in patients in whom the joint is healthy. In patients with osteoarthritis and an abnormal acetabulum, hemiarthroplasty has been abandoned.

2. Total replacement arthroplasty. If both surfaces are replaced, the result is anatomically better than a hemiarthroplasty and would be the ideal operation if the results were consistently good. This is not so. If the joint becomes infected or the components loosen (p. 398), the results are poor and may be worse than before operation.

Salvage of a loose or infected prosthesis is difficult. Excision arthroplasty is always available but is not ideal in weight-bearing joints because so much bone must be removed that later arthrodesis is impossible. In some circumstances amputation may be necessary as a salvage procedure.

Summary

• Drugs and operation are sometimes needed for patients with osteoarthritis, but not always.

• Management depends on careful assessment of the precise local and general problems for the individual patient.

• Simple non-invasive measures are often the best.

• Much depends on a positive and optimistic approach.

• Polypharmacy and multiple operations should be avoided but the belief that ‘nothing can be done’ may be just as damaging.