Chapter 29 Osteoarthritis

Introduction

Although diseases with the greatest consequent mortality (e.g. CVD, cancer) attract much of the public’s attention, musculoskeletal or rheumatic diseases are the major cause of morbidity throughout the world, having a substantial influence on health and quality of life, but not mortality, and inflicting a vast burden of cost on health systems. Musculoskeletal disease is a major cause of disability and handicap, and arthritis is the most prevalent form of musculoskeletal disease.1 Rheumatic diseases include more than 150 different conditions and syndromes with the common denominators being pain and inflammation. Five account for 90% of the cases — osteoarthritis (OA), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), fibromyalgia, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and gout.1–4

Arthritis is a chronic disease affecting an estimated 43 million (20.8%) US adults and is the leading cause of disability in that country3 with OA reported to be the most common joint disorder in the world.4 In Western populations it is one of the most frequent causes of pain, loss of function and disability in adults. Radiographic evidence of OA occurs in the majority of people by 65 years of age and in about 80% of those aged over 75 years. In Australia in 2004, there were 3.4 million people (17% of the population) suffering from some form of arthritis, with 60% of these being females. Of this total, 1.39 million had OA and more than 438 000 had RA.5 Table 29.1 summarises the symptoms of OA.

Integrative management of osteoarthritis

The early 1990s saw an upsurge of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use, based on reports that recognised the extensive use of treatments outside the realm of conventional medicine.6, 7 A recent review reported that patients with musculoskeletal conditions often employ CAM modalities8 in one form or another. Collectively the evidence demonstrates that some CAM modalities show significant promise, as for example herbal medicines, nutritional supplements, acupuncture, and mind–body medicine.

International expert panels have developed useful patient-focused, evidence-based integrative consensus recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis.9, 10

These recommendations include those listed below.

Environment

Despite popular belief arthritic pain has no seasonal variation and is not more common in winter according to a study of 1424 patients with osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis or fibromyalgia followed up over 24 years.11

However, associated atmospheric change and cold temperatures did impact on pain severity according to a study of 200 patients with OA. The authors postulated that the changes in cold temperature may contribute to changes in viscosity of synovial fluid which indirectly affects inflammation.12

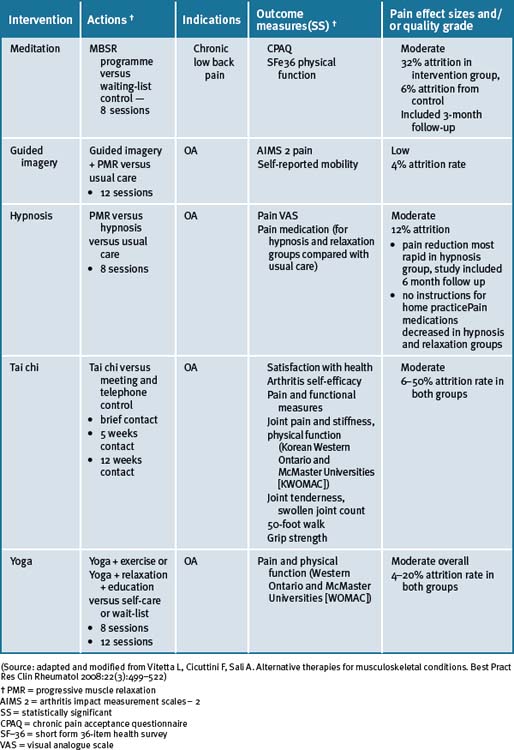

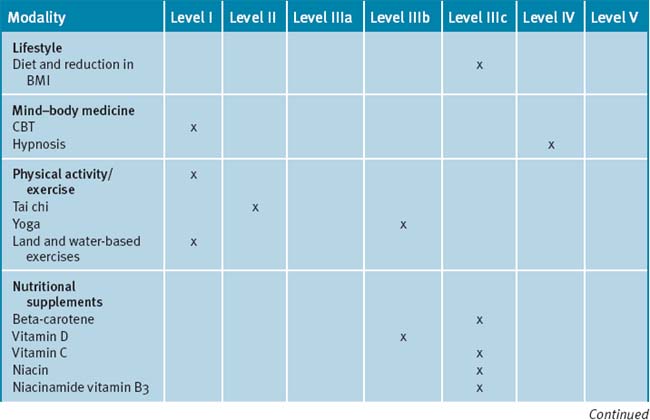

Mind–body medicine

The non-pharmacological management of OA has been recently reviewed.13

Multi-modal cognitive behavioural and/or mind–body therapies, in combination with educational and information components (such as patient education and/or self-management programs) may be appropriate adjunctive treatments in the management of OA.14, 15 Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) has a positive effect on pain and other patient relevant outcomes in chronic pain management due to OA.16, 17 The best effect of CBT has been documented when it was employed together with physical activity as part of a multi-modal treatment program.18 Recent reviews have reported that there is limited evidence available for the role of hypnosis in the management of pain due to OA.14, 15

Physical activity/exercise

In primary care, physical activity is one of the foundations in the management of chronic musculoskeletal pain. Multiple research data supports the benefits of physical activity for alleviation of symptoms of OA; even vigorous exercise.19 A Cochrane review concluded there were no significant differences in benefit between high intensity and low intensity aerobic exercise on participants with OA of the knee for functional status, gait, pain and aerobic capacity.19 Both levels of exercise were beneficial. According to the review of non-pharmacological therapies for OA, exercise (aerobic, range-of-motion and strengthening) should be the leading intervention for OA patients, especially as obesity and being overweight are major risk factors for OA.19 However, recently another Cochrane review concluded that aquatic exercise appeared to have some beneficial short-term effects for patients with hip and/or knee OA while no long-term effects had been reported.20 Based on this data, it is possible to consider using aquatic exercise as the first part of a longer exercise program for OA patients.21

Both function and pain benefit from aerobic or strengthening activity for knee OA. This was confirmed in an RCT with older participants.22 Older disabled persons with OA of the knee had modest improvements in measures of disability, physical performance, and pain from participating in either an aerobic or a resistance exercise program. These data suggest that exercise should be prescribed as part of the treatment for knee OA.

In a recent 18 month clinical study investigating additive effects of glucosamine or risedronate for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee combined with home exercise,23 it was reported that there was improvement after 18 months in all groups using individual scales for evaluation of pain and function of the knee, however, with no significant differences observed between the groups. There were no additive effects of glucosamine or risedronate on the exercise therapy.23

Of interest, a large-scale study of 1279 middle-aged to elderly persons without knee OA (mean age 53.2 years; many of whom were classified as obese) who underwent both baseline and follow-up examinations after 9 years found that neither recreational walking, jogging, frequently working up a sweat, nor high activity levels relative to peers or even weight factors (Body Mass Index [BMI] above the median [7.7 kg/m2 for men and 25.7 kg/m2 for women]; mean BMI >30 kg/m2 for both) did not protect against nor increased the risk of developing knee OA.24

Tai chi and yoga

A recent systematic review has reported that there was some encouraging evidence suggesting that tai chi may be effective for pain control in patients with knee OA.25 However, the evidence was not persuasive for pain reduction or improvement of physical function. A prospective randomised control clinical trial of tai chi over a 12-week period demonstrated significant improvements in self-efficacy for arthritis symptoms (other than pain and function), total self-efficacy, tension levels and general health status, while pain and some lower limb functional scores showed moderate but not clinically significant improvements among older adults.26

A number of small studies have demonstrated that tai chi was effective for a number of people in different environments for the management of pain due to OA.27–30 In 1 study these findings supported the practice of tai chi as beneficial for gait kinematics in elderly people with knee OA.27 A longer-term application was suggested in order to substantiate the effect of tai chi as an alternative exercise in management of knee OA. A further study concluded that access to either hydrotherapy or tai chi classes could provide large and sustained improvements in physical function for many older, sedentary individuals with chronic hip or knee OA.28 In a 12-week study of the efficacy of tai chi to improve physical function, the study results demonstrated that the tai chi group reported lower overall pain and better WOMAC (Western Ontario and McMaster Universities) Osteoarthritis Index gauge physical function than the attention control group at weeks 9 and 12.29 All improvements disappeared after tai chi training ceased. In a study with older women with OA who were able to safely perform the 12 forms of sun-style tai chi exercise for 12 weeks, it was reported effective in improving arthritic symptoms, balance, and physical functioning.30 A longitudinal study with a larger sample size was suggested as necessary to confirm the potential use of tai chi exercise in arthritis management.

In a case series study investigating yoga and strengthening exercises for people living with OA of the knee, the study found functional changes and improvement in quality of life in traditional exercise and a yoga based approach.31 A single small study of the use of yoga for OA of the hands demonstrated improvements in pain and finger range of motion as compared to a control group.32

Nutritional influences

Diets

Obesity is a well-recognised risk factor for increased risk of OA, particularly of the knee and hip.33 A recent study showed that a high BMI was associated with progression of loss of joint-space width associated with knee OA but not hip OA.34 Dietary advice and intervention clearly have a place in musculoskeletal diseases and allow patients to experience some control over their own disease. Although there is no evidence for efficacy of trendy diets, a significant proportion of patients diagnosed with OA can benefit from excluding foods individually identified during the reintroduction phase of an elimination diet.35 Also a proportion of patients who follow a vegetarian or Mediterranean-type diet will experience a significant benefit.

Extra-virgin olive oil contains oleocanthol which acts as a natural anti-inflammatory, and may be of benefit for arthritic joint pains.36

Obesity and high BMI are also associated with more severe disease in terms of the amount of pain experienced37 and the need for joint replacement.38, 39

Dietary nutritional habits are an unavoidable widespread exposure for people for the development of chronic diseases that include musculoskeletal problems.39, 40 The Mediterranean diet reflects the dietary patterns characteristic of several countries in the Mediterranean basin during the 1960s. Typically, the diet comprises abundant plant foods that includes fruits, vegetables, wholegrain cereals, beans, nuts and seeds; minimally processed, seasonally fresh and locally grown foods; fish and poultry; olive oil as the main source of lipid, with dairy products, red meat and wine in low to moderate amounts.35, 40 Lifestyle changes that include adopting daily physical activity and smoking cessation together with changes in nutritional/dietary manipulations may lead to positive effects on musculoskeletal physiology with a consequent beneficial impact on the population health.

Early epidemiological studies have reported that diets rich in vitamins C and D slow progression of OA.41

Nutritional supplements

General

Dietary supplements, commonly referred to as natural medicine/compounds, and herbal medicines account for approximately $20 billion of annual sales in the US alone.8

A large number of dietary supplements are promoted to patients with osteoarthritis and as many as one-third of those patients have used a supplement to treat their condition.8 These sales for complementary medicine products indicate that glucosamine-containing supplements are among the most commonly used products for osteoarthritis.8 Glucosamine is available in multiple forms; the most common being glucosamine hydrochloride and glucosamine sulfate. Some marketed products contain a blend of these and many combine one of the forms with a variety of other ingredients.

Vitamins

Vitamin C and β-carotene

Perhaps the best study of vitamin C was the Framingham OA Cohort Study which demonstrated vitamin C intake was associated with reduced progression of arthritis in OA patients and lower incidence of knee pain.42 Specifically, a significant threefold reduction in risk of OA progression was reported, which related predominantly to a reduced risk of cartilage loss. This was documented for both the middle and the highest tertile of vitamin C intake. Those with high ascorbate intake also had a significantly reduced risk of developing knee pain. A significant, though less consistent, reduction in risk of OA progression was also seen for beta-carotene.42 Recently it has been reported that there was a beneficial effect with vitamin C intake on the reduction in bone size and the number of bone marrow lesions, both of which are important in the pathogenesis of knee OA.43, 44

Niacinamide

Small early trials have reported individual benefits with other vitamins. Namely, a double-blind control trial study of 72 OA patients treated with 3000mg/day in 6 divided doses of niacinamide over 12 weeks demonstrated improved pain scores, reduced global impact of OA, improved flexibility and reduced inflammatory markers (ESR) when compared to controls. Furthermore, the use of NSAIDs was reduced with use of niacinamide.45

Pantothenic acid

A small trial of 26 patients supplemented with 12.5mg/day pantothenic acid reported relief in severity of OA. However 3 patients reported the onset of general anaesthesia and leg weakness with the dosage, for which 12.5mg/day of pyridoxine was administered to elicit recovery.46

Folic acid and vitamin B12 cyanocobalamin

Folic acid (6400mcg) and cyanocobalamin (20mcg) consumed orally over a 2-month period demonstrated greater improvements in hand grip and number of tender joints when applied to 26 patients with OA of the hands when compared to NSAIDs.47 All of these studies require follow-up with properly designed trials.

Antioxidants

A recent systematic review concluded that there is presently no convincing evidence that antioxidants such as selenium, vitamin A, vitamin C or the combination product selenium ACE is effective in the treatment of any type of arthritis.48

Vitamin D

Vitamin D emerges as a vitamin that could stimulate the synthesis of proteoglycan by articular chondrocytes.49 This effect was explored within the Framingham OA Cohort Study.50 In the 556 participants who had complete assessments, a significant threefold to fourfold increase in risk of progression of radiographically determined OA was seen in the middle and low tertiles of vitamin D intake and serum concentration.48 Also, the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group showed that high serum concentrations of vitamin D protected against both incident and progressive hip OA.51 In more recent results from 2 longitudinal cohort studies the Framingham Offspring cohort (715 subjects) and the Boston Osteoarthritis of the Knee Study (277 participants),52 no association was found between baseline 25(OH)D concentration and radiographic deterioration of joint-space narrowing or cartilage loss. Though the evidence is contradictory for OA, the wide prevalence of vitamin D deficiency and the broad range of important roles played by vitamin D suggest that even OA patients should be encouraged to optimise their vitamin D status.53, 54, 55

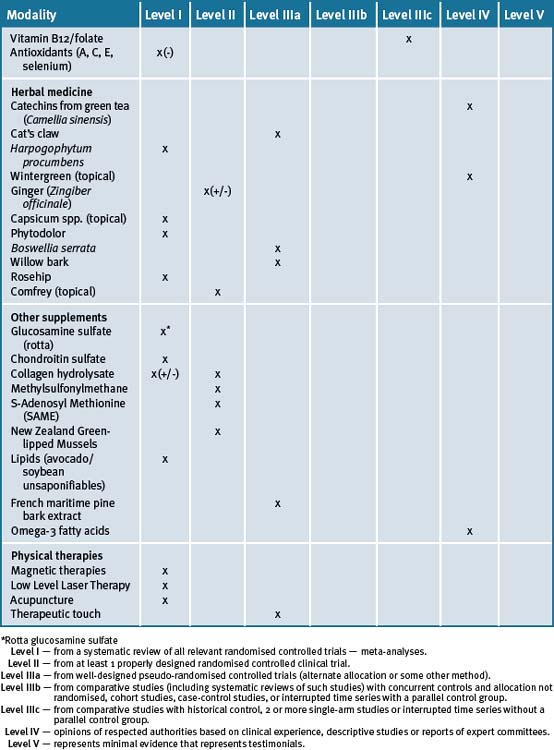

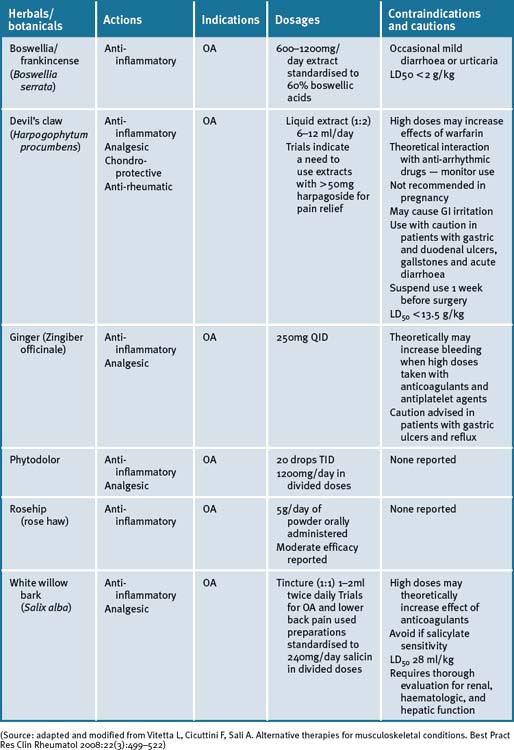

Herbal medicines

A number of herbal supplements have been investigated for their efficacy in patients with OA (see Table 29.3, at the end of this section).56–60

Green tea extract (Camellia sinensis)

The anti-inflammatory and pharmacological properties of green tea extracts have been attributed to the high content of polyphenols/catechins, of which epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) predominates.58, 61 The emerging molecular evidence thus far gives strong biological plausibility support to the in vitro observations that catechins extracted from green tea can exhibit both anti-inflammatory and chondro-protective effects and hence may be beneficial for the management of arthritis.61

Cat’s claw (Uncaria tomentosa, Uncaria guianensis)

Extracts of cat’s claw have been shown to possess antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and immuno-modulating properties.57, 58 The most investigated of the active constituents in Uncaria tomentosa extract for immuno-modulating and anti-inflammatory effects are pentacyclic oxindole alkaloids, which are reported to induce an immune regulating factor.58 In a recent review57 the mechanism of cat’s claw action was postulated to be through the inhibition of TNF-alpha. A small study has reported the safe and effective use of cat’s claw in OA of the knee with U guianensis versus placebo.62

Other research groups have documented the safety and pharmacological profile of cat’s claw.57, 63, 64, 65 There is a requisite though for rigorously testing the effectiveness of the recommended doses, which are considered non-toxic, and there are no known contraindications or drug interactions noted at this stage. Until a full pharmacokinetic profile is investigated it would be prudent to avoid its use in women attempting pregnancy, during pregnancy and lactation.57

Devil’s claw (Harpogophytum procumbens)

Harpogophytum procumbens has been shown to be effective for OA in 2 reviews.65, 66 There is little evidence of efficacy for extracts containing less than 30mg/day of the active constituent, harpagoside, and that a correct dose is >50mg/day for OA of the knee and hip. Devil’s claw exhibits cellular signalling modulating activities that down-regulate inflammatory markers.67, 68, 69 A Cochrane review of five randomised clinical trials (RCTs) have reported on the effects of devil’s claw in the treatment of OA.70 Of these, 3 were placebo-controlled and 2 were compared to common pharmaceuticals (diacerhein and phenylbutazone). Three trials demonstrated significant positive results, while 2 studies that employed less than 30mg harpagoside recorded results that were less significant.70 An aqueous extract of devil’s claw (consisting of 60mg harpagoside) was found to be as effective as 12.5mg of rofecoxib for the treatment of acute non-specific lower-back pain in a double-blind pilot RCT.70 Three other trials have also demonstrated efficacy in lower back pain, with 100mg of harpagoside, considered superior, when neurological deficits are present.69, 70 A recent systematic review71 has reported a prevalence of 3% of gastrointestinal complaints in 20 of 28 clinical trials investigated. A few reports of acute toxicity were found (e.g. gastrointestinal complaints, allergies) but there were no reports on chronic toxicity, perhaps due to the low doses utilised in most of the studies.71

Ginger (Zingiber officinale)

The fresh and/or dried roots of Zingiber officinale are reported to possess anti-inflammatory, antiseptic and carminative properties and has been used to treat inflammatory and rheumatic diseases.72 The pungent phenolic constituent of ginger, 6-gingerol, has been shown to inhibit LPS-induced iNOS expression and production of NO in macrophages and to block peroxynitrite-induced oxidation and nitration reactions in vitro.72–74 Cumulative laboratory animal data suggest that 6-gingerol is a potent inhibitor of NO synthesis and effective in inhibiting production of PGE2 and TNF-alpha and COX-2 expression in human synoviocytes by regulating NFκB activation and degradation of its inhibitor IkBa subunit.72

A recent RCT of a combined extract of the herbs Zingiber officinale and Alpinia galanga, comprising 255mg extracted from 2500–4000mg ginger and 500–1500mg galanga rhizome respectively, demonstrated a positive effect on knee OA.75 Clinical trial participants in the ginger/galangal combined extract group experienced a 63% reduction in knee pain on standing versus 50% in the placebo group.75 The highly purified and standardised extract had a statistically significant effect on reducing symptoms of OA of the knee with a high safety profile, and mild GI adverse events in the ginger extract group.75 In a further cross-over RCT, in patients with OA, the ginger extract showed statistically significant efficacy in the first period of treatment before cross-over, however a significant difference was not observed in the study overall.76

Wintergreen (Gaultheria yunnanensis)

Topical natural products that include liniments, balms, creams, gels, oils, lotions, patches, ointments and other products that are applied to the skin are often sought with the intent to provide pain relief for mild arthritis pain that affects only a few joints, as well as to ease sore muscles, back pain and OA.77, 78 No clinical trials are currently available to evaluate these effects. However, in vivo studies have shown that a salicylate fraction isolated from wintergreen has analgesic and anti-inflammatory properties.79 Caution, even with topical products, is required in patients receiving warfarin as adverse interactions and bleeding have been reported to be a risk with its use.80

Phytodolor

Phytodolor is a herbal proprietary product that includes aspen (Populus tremula), goldenrod (Solidago virgaurea) and golden ash (Fraxinus excelsior). Although most of the available literature is German, a recent systematic review of 6 RCTs which included the German studies concluded that Phytodolor reduced the pain associated with rheumatic disorders.80 The dose administered was 30 drops TID for 3 of the trials and 40 drops TID for the remainder, with duration ranging from 2 to 4 weeks.

Boswellia and/or frankincense (Boswellia serrata)

Boswellia serrata (boswellia) is a popular Ayurvedic herb that is purported to exhibit effective analgesic, anti-inflammatory and anti-arthritic activity.81–84 A recent RCT assessed the efficacy, safety and tolerability in 30 patients with OA of the knee over a 16-week period.84 Patients receiving 333mg of boswellia extract containing 40% boswellic acid, 3 times daily, reported a significant decrease in knee pain and swelling, and an associated increase in function and range of movement. Adverse reactions of boswellia therapy were uncommon and included diarrhoea, epigastric pain, and nausea, all of which responded to simple symptomatic management.84 A further RCT compared the same extract with valdecoxib, a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug in 66 patients with knee OA over 6 months. This study has a slower onset of action with pain relief persisting for 1 month after ceasing treatment, while valdecoxib acted faster but lasted only during therapy.85

White bark

There is a resurgence of interest in willow bark as a treatment for chronic pain syndromes associated with OA. While white willow (Salix alba) is the willow species most commonly used for medicinal purposes, crack willow (Salix fragilis), purple willow (Salix purpurea), and violet willow (Salix daphnoides) are all salicin-rich species and are available under the label of willow bark. RCTs of short duration have provided evidence of efficacy.86

Historically, Hippocrates was known to prescribe the bark and the leaves of the white willow bark to help relieve pain and fever.86 In 1832, a German chemist produced salicylic acid from salicin, the active ingredient in willow bark. Acetyl salicylic acid was used to produce aspirin and is the more stable form, widely used internationally.86

Rosehip (rose haw)

Recent systematic searches of the literatures,87, 88 have demonstrated that rosehip powder or the seeds of the Rosa canina subspecies had a moderate effect in patients with OA. A study that enrolled 94 patients with OA of the hip or knee in a double-blind placebo-controlled (DBPC) cross-over trial,89 reported that the 47 patients who were given 5g/day of the herbal remedy for a period of 3 months, resulted in a significant reduction in WOMAC pain (P<0.014) as compared to placebo, when testing after 3 weeks of treatment. Furthermore, the clinical data suggested that the herbal remedy not only alleviated symptoms but also reduced the consumption of ‘rescue medication‘ for pain relief.

A recent meta-analysis of the literature identified 3 randomised control trials (RCTs) inclusive of 287 patients over a mean 3-month period and demonstrated rosehip powder significantly reduced OA pain compared with placebo, although long-term studies are required to assess its long-term efficacy and safety.90

Comfrey (Symphytum officinale L)

A recent randomised, double-blind, bi-centre, placebo-controlled clinical trial investigated the effect of a daily application of 6g (3 x 2g) of a commercially available preparation labelled as Kytta-Salbe® f over a 3-week period with patients suffering from painful OA of the knee.91 The results documented suggested that the comfrey root extract ointment was significantly appropriate for the treatment of OA of the knee. Pain was reduced, mobility of the knee improved and quality of life increased.

French maritime pine bark extract

A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of 100 patients with mild-moderate knee OA who were treated for 3 months with either 150mg French maritime pine bark extract once daily at meals or by placebo demonstrated reduction of symptoms in the treated group.92 Patients on the herbal extract reported an improvement of WOMAC index, significant alleviation of pain and reduction of analgesia use compared with no effect with placebo. The pine bark extract was well tolerated and postulated to have anti-inflammatory actions.92

Capsaicin (Capsicum frutescens)

A recent systematic review has concluded that topically applied capsaicin has moderate to poor efficacy in the treatment of chronic musculoskeletal or neuropathic pain. Further, that it could be useful as an adjunct or sole therapy for a small number of patients who are unresponsive to, or intolerant of, other treatments.93

Other supplements

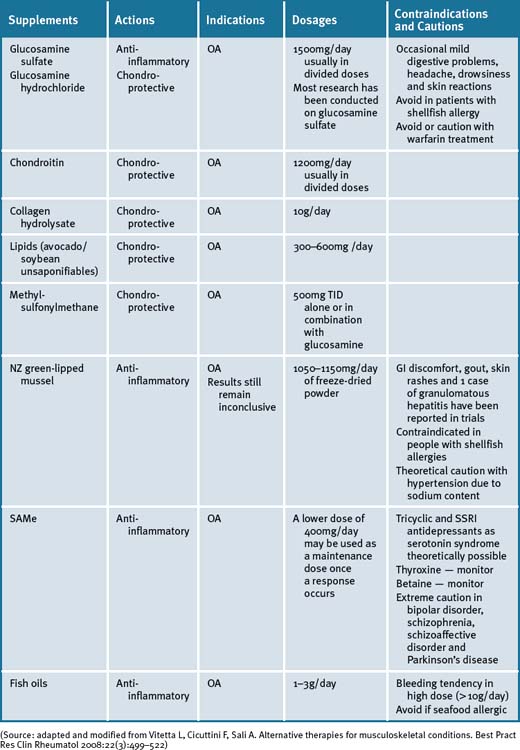

Glucosamine

Even though the therapeutic effectiveness of glucosamine treatment on OA has been demonstrated by improved mobility and relief of pain in animal models as well as in RCTs94 its effectiveness as a symptom and disease modifier for OA is still under debate. A recent meta-analysis concluded that the evidence for efficacy for improving symptoms in OA was conflicting and that glucosamine hydrocholoride was not effective.95 A recent study reported that glucosamine sulfate was no better than placebo in reducing symptoms and progression of hip OA.96

A Cochrane review concluded that a specific type of glucosamine sulfate supplement (from Dona, Rotta Pharmaceuticals, Inc) was superior to placebo in the treatment of pain and functional impairment resulting from symptomatic OA.97 Results for the non-Rotta preparation were not statistically significant. The review analysed data from 20 RCTs involving 2570 participants, of which 10 RCTs used the Rotta preparation. A second systematic review reviewed RCTs of at least 1 year’s duration.95 It was reported that glucosamine sulfate may be effective and safe in delaying the progression and improving the symptoms of knee OA. A previous Cochrane review of 16 RCTs had found that glucosamine was effective, however, these included smaller trials with less methodological rigor.98

A concern with most trials of glucosamine sulfate, glucosamine hydrochloride and chondroitin sulfate in the treatment of OA was weak research designs that had been employed.99 The Glucosamine/Chondroitin Arthritis Intervention Trial (GAIT) was designed to address these inconsistencies and provide some clarity on the effectiveness of glucosamine (1500mg/day) and chondroitin (1200mg/day) for the treatment of knee pain in OA by employing a rigorous research design.100 The GAIT found that glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate, alone or in combination, did not significantly reduce OA knee pain more than placebo.100 A combination of glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate was found to be effective in a subgroup of patients with moderate-to-severe knee pain (79.2% versus 54.3% for placebo).100 The combined emerging data suggests that glucosamine has a structure-modifying effect. However, debate remains regarding this, largely in relation to methodological issues surrounding outcome measures used in the positive studies.

It has been reported that there is extensive heterogeneity among trials of glucosamine and that this is larger than would be expected by chance. Glucosamine hydrochloride does not appear to be effective.101 Among trials with industry involvement, effect sizes were consistently reported to be higher. The potential explanations may include different glucosamine preparations, inadequate allocation concealment, and industry bias.101

Chondroitin sulfate (CS)

An RCT employing chondroitin sulfate (GS) on 40 patients with tibio-fibular OA of the knee, were allocated to receive 50 intramuscular injections (one injection twice weekly) for 25 weeks. CS had a significantly greater therapeutic effect on all symptoms evaluated.102 No important local or systemic side-effects were noted.102 Favourable effects have been reported in pain reduction and improvement in mobility when CS was given either intra-articularly or orally to elderly patients with joint degeneration.103

A double-blind RCT with 104 patients receiving oral chondroitin-4-sulfate and chondroitin-6-sulfate (CS4 and CS6) at a dose of 800mg/day or placebo for 1 year showed CS4 and CS6 had a beneficial effect, both in terms of clinical manifestations and anatomic progression, in patients with OA of the knee.104 The main efficacy criterion was the Lequesne’s functional index (LFI). Functional impairment was reduced by approximately 50%, with a significant improvement over placebo for all clinical criteria. Tolerance was excellent or good in more than 90% of cases. This study suggests that CS act as structure modulators as illustrated by improvement in the interarticular space visualised on x-rays of patients treated with CS4 and CS6.104

A double-blind RCT of 42 patients with symptomatic OA of the knee examined the effect of 400mg CS twice daily for 1 year.105 After 3 months, joint pain was significantly reduced in the CS group compared to the placebo group. This difference became more pronounced after 12 months. The increase in overall mobility capacity was significantly greater at 6 and 12 months in the CS group than in the placebo group. After 1 year, the mean width of the medial femoro-tibial joint was unchanged from baseline in the CS group, but had decreased significantly in the placebo group. Although no statistical comparison was presented for the change in joint-space width between the 2 groups, the finding suggests the possibility CS treatment may slow the progression of OA.105 The proprietary chondroitin sulfate was studied in a further double-blind RCT of 85 patients with OA of the knee. Participants received Condrosulf® at a dose of 400mg twice daily or placebo for 6 months. Lequesne’s index, spontaneous joint pain, and walking time all decreased progressively in the CS group, with a significant difference in favour of the CS group for each of these parameters.106 In a double-blind RCT parallel group study using either CS 1g/day or placebo on 130 patients for 3 months followed by a 3-month post-treatment period, the CS group experienced greater but non-significant improvement than the placebo group at the treatment endpoint, as measured by the LFI. Improvement became significant in the completer population. In the intent-to-treat population, all variables tended toward greater improvement in the CS than the placebo group. One month after treatment, CS had a significantly higher persistent effect than placebo on the LFI, pain with activity, and other efficacy criteria. Adverse event rates did not differ significantly.107

To assess the clinical efficacy of CS in comparison with the NSAID diclofenac sodium, a multi-centre double-blind RCT, double-dummy study on 146 patients was conducted for 6 months.108 Patients treated with diclofenac showed prompt reduction of clinical symptoms that reappeared, however, after the end of treatment. In the CS group, the therapeutic response appeared later but lasted up to 3 months after the end of treatment. It was concluded that CS had slow but gradually increasing clinical activity in OA, and these benefits lasted a long period after the end of treatment. Shortcomings in these studies were that they involved only a relatively small number of patients and no dose-finding investigations for CS could be found.

A double-blind prospective RCT study of 300 patients given a proprietary registered brand of chondroitin sulfate 800mg/day or placebo for 2 years investigated the structure-modulating properties of CS in gonarthrosis by measuring the modifications in minimum joint space width (JSW), mean thickness, and mean surface of the cartilage in internal femoro-tibial function.109 There was a significant difference, with worsening of the arthritis in the placebo group compared to the CS group. In the group treated with CS, there were no significant variations in any radiological parameters, which remained remarkably stable. The statistical analysis revealed a significant difference in the CS group compared to the placebo group in regard to maintenance of the cartilage analysed, in both the intent-to-treat analysis and also in the per-protocol of analysis subjects who completed the study protocol. It was shown that CS was superior to placebo with regard to stabilisation of minimum JSW of the internal femoro-tibial articular space, the mean thickness, and the surface.109 Hence there is sufficient controlled trial data to support the use of CS in symptomatic OA, having less side-effects than currently used NSAIDs. Chondroitin sulfates appear to have a role in prevention of disease progression. The requisite is that CS be further evaluated in studies of longer treatment duration, with larger numbers of patients, and using well-established measures of function and progression.

A recent meta-analysis reporting on a set of poor to moderate quality, largely heterogeneous (in methodology) trials that made interpretation of the data difficult, concluded that the results were unreliable. Further, the authors concluded that since large-scale, methodologically sound trials indicate that the symptomatic benefit of chondroitin is minimal or nonexistent, that chondroitin cannot be recommended.110

Despite these findings a recent well-performed long-term double-blind study of 622 patients with knee OA, randomised to 800mg of CS or placebo once daily for a 2-year period, demonstrated significant pain relief and radiological improvement by way of demonstrable reduction in minimum JSW loss on X-Rays in the CS group as compared with the placebo group.111

Collagen hydrolysate

Four open label and 3 double-blind trials have been reported in a review of the literature.112 In a 24-week multi-country double-blind RCT on knee OA, 10g/day of collagen hydrosylate did not improve the WOMAC index.113 Post-study analysis suggested that the hydrolysate could be more efficient in severe OA. A 60-day cross-over double-blind RCT on knee and hip OA compared 10g/day of collagen hydrolysate, gelatin, gelatin + glycin + calcium phosphate, or egg albumin114 and found the gelatin preparations were not significantly different from each other and were superior to egg albumin in reducing pain as assessed by a patient questionnaire. According to the best evidence, efficacy for collagen hydrolysate is equivocal. However, a recent systematic review points to a growing body of evidence and provides a rationale for the use of collagen hydrolysate for patients with OA.112

Methylsulfonylmethane (MSM)

In a 12-week double-blind RCT on knee OA, 500mg of methylsulfonylmethane TID used alone, or in combination with 500mg of glucosamine HCl 3 times a day, significantly improved a Likert scale of pain and LFI.115 The combination of both ingredients was not more efficacious than each ingredient used alone. In a further 12-week double-blind RCT on knee OA, 3g of methylsulfonylmethane given twice daily was more efficient than placebo in decreasing WOMAC pain and functional scores.116 According to the best-evidence synthesis, MSM provides moderate evidence of efficacy for knee OA.117

S-Adenosyl Methionine (SAMe)

A practical amount of research evidence exists to support the use of SAMe for the treatment of pain associated with OA.118 A meta-analysis of 11 RCTs comprising 1442 participants with an average age of 60.3 years from 2002, demonstrated that SAMe is as effective as NSAIDs in reducing the pain of OA, with significantly fewer side-effects.119

New Zealand green-lipped mussel (Perna Canaliculus)

The reported incidence of arthritis in coastal-dwelling Maoris is low, and it has been suggested that this is possibly due to their high consumption of green-lipped mussels.120 However, results from clinical trials have been inconsistent, with a recent review concluding that there is little consistent and compelling evidence, to date, in the therapeutic use of freeze-dried green-lipped mussel powder products for RA and OA treatment but that further investigations are warranted.120 Recently a study was conducted to validate the clinical efficacy and safety of Lyprinol (a patented extract from Perna Canaliculus), a 5-LOX inhibitor in patients with OA.121 The results demonstrated that after a 4- and 8-week treatment period, 53% and 80% (respectively) of the trial participants experienced significant pain relief, and improvement of joint function. There was no reported adverse effect during the trial.

Lipids (avocado/soybean unsaponifiables)

Four double-blind RCTs and 1 systematic review have evaluated avocado/soybean unsaponifiables (ASUs) on knee and hip OA.122–127 In two 3-month RCTs, 1 on OA of the knee only123 and 1 on knee and hip OA,125 300mg once a day decreased NSAID intake. The efficacy of ASU at a dosage of 300mg/day and 600mg/day was consistently superior to that of placebo at all endpoints.123 However, no statistical difference in any primary or secondary endpoints was detected between 300 and 600mg once a day.123 In a 3-month RCT on knee and hip OA, 300mg once a day resulted in an improved LFI compared with placebo.124 ASUs had a 2-month delayed onset of action as well as residual symptomatic effects 2 months after the end of treatment.124 In a 2-year RCT on hip OA, 300mg once a day did not slow down narrowing of JSW.125 In addition, none of the secondary endpoints LFI, visual analogue scale of pain, NSAID intake, and patients‘ and investigators‘ global assessments was statistically different from placebo after 1 year. However, a post-hoc analysis suggested that ASUs might decrease narrowing of JSW in patients with the most severe hip OA.125

Although ASUs might display medium-term symptom-modifying effects on knee and hip OA, their symptom-modifying effects in the long term (>1 year) have not been confirmed. Based on the best-evidence synthesis, ASUs is good for symptom-modifying effects in knee and hip OA with some evidence of absence of structure-modifying effects. A recent systematic review on ASUs recommended further investigation because 3 of the 4 rigorous RCTs suggest that ASUs is an effective symptomatic treatment, but the long-term study was largely negative.126

A Cochrane review identified 5 studies (4 different herbs) that met the criteria for the treatment of OA.127 Two studies of ASU extracts showed beneficial effects on function, reduced pain, reduced requirement for NSAID medication and increased global evaluation. There were no serious side-effects reported. The reviewers concluded the evidence for ASUs in the treatment of OA is convincing but evidence for the other herbal interventions is insufficient to either recommend or discourage their use.128

Fish oils/omega-3 (n-3) fatty acids

There are currently no RCTs on the effect of n-3 fatty acids in OA. However, there are suggestions that supplementation with long-chain n-3 PUFA may be beneficial for those with active/inflamed OA joints.35 In a recent review, the authors reported that in a small unpublished trial carried out in Wales, OA patients supplemented with cod-liver oil showed reduced COX-2 expression and COX-2 protein levels and that the levels of inflammatory eicosanoids were reduced in some cases.35

Physical therapies

Hydrotherapy/water-based exercises

It is well known that hydrotherapy and water-based exercises can provide symptomatic relief of pain and improve joint flexibility for OA patients. A recent randomised study aimed to compare the outcomes between land-based and water-based exercise programs (1 hour sessions twice weekly) in 102 patients, 2 weeks after a total knee replacement, for up to 6 months and found equally significant improvements observed in both groups for joint pain, stiffness, flexibility and leg oedema.128

Acupuncture

Recent meta-analysis and systematic review concluded that acupuncture procedures that meet criteria for adequate treatment were significantly greater to sham acupuncture and to no additional intervention in improving pain and function in patients with chronic knee pain that was due to OA.129, 130, 131 These recent studies confirm an earlier systematic review and meta-analysis that concluded that:

There is, however, due to the nature of the heterogeneity in the results, a requisite for further research to confirm these findings and provide more information on long-term effects.131

Magnetic therapies, TENS and low level laser therapy (LLLT)

Whilst research in the past showed magnetic therapy to be promising for the stimulation of cartilage growth in in vitro studies, a recent Cochrane review of 259 OA patients found small to moderate effects on outcomes for knee OA.132 All outcomes were statistically significant with clinical benefit ranging from 13–23% greater with active treatment compared with placebo. The reviewers concluded that there was a significant need for further large-scale studies of pulsed electric stimulation with a focus on knee OA to establish the clinical relevance of this treatment for the management of OA.132

LLLT is a light source that generates extremely pure light, of a single wavelength. LLLT was introduced as an alternative non-invasive treatment for OA about 20 years ago, but its effectiveness is still controversial. A recent Cochrane review identified 7 trials of 184 patients randomised to laser and 161 patients to placebo laser.133 Treatment duration ranged from 4 to 12 weeks. Pain was assessed by 4 trials. Three trials showed very positive effects on pain relief and 3 trials found no effect. Only 1 patient reported an erythema as a side-effect, and was then excluded for the rest of the study. Lower dosage of LLLT was found to be as effective as the higher dosage for reducing pain and improving knee range of motion.133 In another trial with no scale-based pain outcome, significantly more patients reported pain relief (yes/no) with laser with an odds ratio of 0.05, (95% CI: 0.0 to 1.56). Of the 7 studies only 1 study found significant results for increased knee range of motion (WMD: −10.62 degrees, 95% CI: −14.07,−7.17). Other outcomes of joint tenderness and strength were not significant. The review concluded that there was an urgent need for further large-scale studies of laser therapy for OA. In particular, the application of laser therapy to the nerve as well as the joint was shown to be beneficial in 1 trial.133

Recently, a systematic review of physical treatments was conducted with meta-analysis of efficacy within 1–4 weeks and at follow up at 1–12 weeks after the end of treatment.134

The patient cohort had a mean age of 65.1 years and mean baseline pain of 62.9mm on a 100mm visual analogue scale. Within 4 weeks of the commencement of treatment manual acupuncture, static magnets and ultrasound therapies did not offer statistically significant short-term pain relief over placebo. Pulsed electromagnetic fields offered a small reduction in pain of −6.9mm. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), including interferential currents, electro-acupuncture and low LLLT, offered clinically relevant pain relieving effects of −18.8mm, −21.9mm and −17.7mm respectively, versus placebo control.134

Therapeutic touch

A single randomised control trial of 82 non-institutionalised patients with knee OA were randomised to therapeutic touch, or progressive muscle relaxation. The treatment group noted significant improvement in pain and distress compared with the muscle relaxation group who also had improvements in pain scores.135 The differences in effectiveness existed between the therapeutic touch and progressive muscle relaxation groups. That is, the pain and distress scores were lower in the progressive muscle relaxation group. The differences approached significance for pain and were significant for distress.

Conclusion

Intervention programs often focus on only 1 or a few components in the management of musculoskeletal diseases. There is not 1 single format that can be advised to give an evidence-based approach to every patient. The requisite is therefore for an integrative approach to improve the quality of life for the patient, particularly with the aim to reduce pain and improve function of the joints. This approach may require a multi-team involvement to assist the patient meet their symptom management needs. The cornerstones for the treatment of musculoskeletal conditions hence require implementation of dietary and nutritional/supplement interventions alongside physical activity (other manipulative or appropriate physical modalities), appropriate analgesia (nutritional, herbal or pharmaceutical), and patient education and engagement with a cognitive approach. Table 29.5 summarises the evidence for complementary medicine therapies.

Clinical tips handout for patients — osteoarthritis

1 Lifestyle advice

Sunshine

2 Physical activity/exercise

3 Mind–body medicine

5 Dietary changes

7 Supplements

Fish oils

Vitamins

Vitamin C

Vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol 25mg or 1000 international units)

Doctors should check blood levels and suggest supplementation if levels are low.

Niacinamide/vitamin B3

Pantothenic acid/Vitamin B5

Folic acid and vitamin B12 cyanocobalamin

Check with your health or medical practitioner. Best combined in a multi-B supplement.

Herbal medicines

Green tea (Camellia sinensis)

Devil’s claw (Harpogophytum procumbens)

Ginger (Zingiber officinale)

Wintergreen (camphor/gaultheria yunnanensis), capsaicin topical, stinging nettle

May be combined with glucosamine and chondroitin, pantothenic acid (vitamin B5).

Boswellia/frankincense (Boswellia serrata)

Willow bark (Salix alba)

Willow bark has salycilate-like properties (anti-inflammatory).

Rosehip (rose haw) powder/tea

Other supplements

French maritime pine bark extract

Glucosamine sulfate (preferred)

Chondroitin sulfate

Collagen hydrolysate (gelatine)

This is a purified protein from animal collagen (e.g. pigs and cows); often found in food products.

Methylsulfonylmethane (MSM)

This is a natural compound derived from green plants.

New Zealand green-lipped mussel

Mollusc derived from mussel; rich in omega-3 fatty acids.

1 Siebens H.C. Musculoskeletal problems as comorbidities. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;86:S69-S78.

2 Bergman S. Public health perspective-how to improve the musculoskeletal health of the population. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2007;21:191-204.

3 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Monitoring progress in arthritis management-United States and 25 states 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54:484-488.

4 Arden N., Nevitt M.C. Osteoarthritis: epidemiology. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2006;20:3-25.

5 Arthritis Australia. Online. Available: http://arthritisaustralia.com.au/media/file/Access%20Economics%20Report%202001.pdf [accessed June 2008].

6 Eisenberg D.M., Davis R.B., Ettner S.L., et al. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States 1990–1997: results of a follow-up national survey. JAMA. 1998;280:1569-1575.

7 MacLennan A.H., Myers S.P., Taylor A.W. The continuing use of complementary and alternative medicine in South Australia costs and beliefs in 2004. Med J Aust. 2006;184:27-31.

8 Gregory P.J., Sperry M., Wilson A.F. Dietary supplements for osteoarthritis. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77(2):177-184.

9 Zhang W., Moskowitz R.W., Nuki G., et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, part I: critical appraisal of existing treatment guidelines and systematic review of current research evidence. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007;15(9):981-1000.

10 Zhang W., Moskowitz R.W., Nuki G., et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, Part II: OARSI evidence-based, expert consensus guidelines. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008;16(2):137-162.

11 Hawley D.J., Wolfe F., Lue F.A., et al. Seasonal symptom severity in patients with rheumatic diseases: a study of 1,424 patients. J Rheumatol. 2001;28(8):1900-1909.

12 McAlindon T.M., Fomica, Schmid C.H., Fletcher J. Changes in barometric pressure and ambient temperature influence osteoarthritis pain. Am J Med. 2007;120(5):429-434.

13 Bremander A., Bergman S. Non-pharmacological management of musculoskeletal disease in primary care. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2008;22(3):563-577.

14 Morone N.E., Greco C.M. Mind-body interventions for chronic pain in older adults: a structured review. Pain Med. 2007;8(4):359-375.

15 Astin J.A. Mind-body therapies for the management of pain. Clin J Pain. 2004;20:27-32.

16 Morley S., Eccleston C., Williams A. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials of cognitive behaviour therapy and behaviour therapy for chronic pain in adults, excluding headache. Pain. 1999;80(1–2):1-13.

17 Linton S.J., Ryberg M. A cognitive-behavioral group intervention as prevention for persistent neck and back pain in a non-patient population: a randomised controlled trial. Pain. 2001;90(1–2):83-90.

18 Williams D.A., Cary M.A., Groner K.H., et al. Improving physical functional status in patients with fibromyalgia: a brief cognitive behavioral intervention. The Journal of Rheumatology. 2002;29(6):1280-1286.

19 Brosseau L., MacLeay L., Robinson V., et al. Intensity of exercise for the treatment of osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2):2003. CD004259

20 Bartels E.M., Lund H., Hagen K.B., et al. Aquatic exercise for the treatment of knee and hip osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (4):2007. CD005523

21 March L.M., Stenmark J. Non-pharmacological approaches to managing arthritis. MJA. 2001;175:S103-S107.

22 Ettinger W.H.Jr, Burns R., Messier S.P., et al. A randomised trial comparing aerobic exercises and resistance exercise with a health education program in older adults with knee osteoarthritis. The Fitness Arthritis and Seniors Trial (FAST) JAMA. 1997;277(1):25-31.

23 Kawasaki T., Kurosawa H., Ikeda H., et al. Additive effects of glucosamine or risedronate for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee combined with home exercise: a prospective randomised 18-month trial.J Bone Miner Metab. 2008;26(3):279-287.

24 Felson D.T., Niu J., Clancy M., et al. Effect of recreational physical activities on the development of knee osteoarthritis in older adults of different weights: The Framingham Study. Arthritis Rheumatology. 2007;57(1):6-12.

25 Lee M.S., Pittler M.H., Ernst E. Tai chi for osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Clin Rheumatol. 2008;27(2):211-218.

26 Hartman C.A., Manos T.M., Winter C., et al. Effects of tai chi training on function and quality of life indicators in older adults with osteoarthritis. J Am Geriatrics Society. 2000;48(12):1553-1559.

27 Shen C.L., James C.R., Chyu M.C., et al. Effects of tai chi on gait kinematics, physical function, and pain in elderly with knee osteoarthritis—a pilot study. Am J Chin Med. 2008;36(2):219-232.

28 Fransen M., Nairn L., Winstanley J., et al. Physical activity for osteoarthritis management: a randomised controlled clinical trial evaluating hydrotherapy or tai chi classes. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(3):407-414.

29 Brismée J.M., Paige R.L., Chyu M.C., et al. Group and home-based tai chi in elderly subjects with knee osteoarthritis: a randomised controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2007;21(2):99-111.

30 Song R., Lee E.O., Lam P., et al. Effects of tai chi exercise on pain, balance, muscle strength, and perceived difficulties in physical functioning in older women with osteoarthritis: a randomised clinical trial. J Rheumatol. 2003;30(9):2039-2044.

31 Bukowski E.L., Conway A., Glentz L.A., et al. The effect of iyengar yoga and strengthening exercises for people living with osteoarthritis of the knee: a case series. Int Q Community Health Educ. 2006–2007;26(3):287-305.

32 Garfinkel M., et al. Evaluation of a yoga based regimen for treatment of osteoarthritis of the hands. J Rheumatol. 1994;21(12):2341-2343.

33 Reijman M., Pols H.A., Bergink A.P., et al. Body mass index associated with onset and progression of osteoarthritis of the knee but not of the hip: the Rotterdam Study. Annals of the Rheum Dis. 2007;66:158-162.

34 Marks R. Obesity profiles with knee osteoarthritis: correlation with pain, disability, disease progression. Obesity (Silver Spring Md). 2007;15:1867-1874.

35 Rayman M.P., Pattison D.J. Dietary manipulation in musculoskeletal conditions. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2008;22(3):535-561.

36 Beauchamp G.K., Keast S.J. Phytochemistry Ibuprophen-like activity in extra-virgin olive oil. Nature. 2005;437(7055):45-46.

37 Cooper C., Inskip H., Croft P., et al. Individual risk factors for hip osteoarthritis: obesity, hip injury, and physical activity. Amer J Epid. 1998;147:516-522.

38 Liu B., Balkwill A., Banks E., et al. Relationship of height, weight and body mass index to the risk of hip and knee replacements in middle-aged women. Rheumatology (Oxford England). 2007;46:861-867.

39 Choi H.K. Dietary risk factors for rheumatic diseases. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2005;17(2):141-146.

40 Rayman M.P., Callaghan A. Nutrition and Arthritis. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing; 2006.

41 McAlindon T.E., Felson D.T., Zhang Y., et al. Do antioxidant micronutrients protect against the development and progression of knee osteoarthritis? Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1996;39:648-656.

42 Roemer F.W., Guermazi A., Hunter D.J., et al. The association of meniscal damage with joint effusion in persons without radiographic osteoarthritis: the Framingham and MOST osteoarthritis studies. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008 Oct 17. Epub ahead of print

43 Wang Y., Cicuttini F.M., Vitetta L., et al. What effect do dietary antioxidants have on the symptoms and structural progression of knee osteoarthritis over two years? Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2006;24:213-214.

44 Wang Y., Hodge A.M., Wluka A.E., et al. Effect of antioxidants on knee cartilage and bone in healthy, middle-aged subjects: a cross-sectional study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9(4):R66.

45 Jonas W.B., Rapoza C.P., Blair W.F. The effect of niacinamide on osteoarthritis: a pilot study. Inflamm Res. 1996;45(7):330-334.

46 Annand J. Pantothenic acid and Osteoarthritis. Lancet. 1963;2:1168.

47 Flynn M., et al. The effect of folate and cobalamin on osteoarthritic hands. J Am College of Nutr. 13(4), 1994.

48 Canter P.H., Wider B., Ernst E. The antioxidant vitamins A, C, E and selenium in the treatment of arthritis: a systematic review of randomised clinical trials. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007;46(8):1223-1233.

49 McAlindon T., Felson D.T. Nutrition: risk factors for osteoarthritis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 1997;56:397-402.

50 McAlindon T.E., Felson D.T., Zhang Y., et al. Relation of dietary intake and serum levels of vitamin D to progression of osteoarthritis of the knee among participants in the Framingham Study. Ann Int Med. 1996;125:353-359.

51 Lane N.E., Gore L.R., Cummings S.R., et al. Serum vitamin D levels and incident changes of radiographic hip osteoarthritis: a longitudinal study. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Arthr Rheum. 1999;42:854-860.

52 Felson D.T., Niu J., Clancy M., et al. Low levels of vitamin D and worsening of knee osteoarthritis: results of two longitudinal studies. Arthr Rheum. 2007;56:129-136.

53 Zittermann A. Vitamin D in preventive medicine: are we ignoring the evidence? Br J Nutr. 2003;89:552-572.

54 Hypponen E., Power C. Hypovitaminosis D in British adults at age 45 y: nationwide cohort study of dietary and lifestyle predictors. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2007;85:860-868.

55 Lementowski P.W., Zelicof S.B. Obesity and osteoarthritis. Am J Orthop. 2008;37(3):148-151.

56 Vitetta L., Cicuttini F., Sali A. Alternative therapies for musculoskeletal conditions. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2008;22(3):499-522.

57 Hardin S.R. Cat’s claw: an Amazonian vine decreases inflammation in osteoarthritis. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2007;13(1):25-28.

58 Ahmed S., Anuntiyo J., Malemud C.J., et al. Biological basis for the use of botanicals in osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: a review. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2005;2:301-308.

59 Sharma R.A., Steward W.P., Gescher A.J. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of curcumin. Adv Exp Med Biol.. 2007;595:453-470.

60 Canter P.H., Lee H.S., Ernst E. A systematic review of randomised clinical trials of Tripterygium wilfordii for rheumatoid arthritis. Phytomedicine. 2006;13:371-377.

61 Curtis C.L., Harwood J.L., Dent C.M., et al. Biological basis for the benefit of nutraceutical supplementation in arthritis. Drug Discov Today. 2004;9:165-172.

62 Piscoya J., Rodriguez Z., Bustamante S.A., et al. Efficacy and safety of freeze-dried cat’s claw in osteoarthritis of the knee: mechanisms of action of the species Uncaria guianensis. Inflamm Res. 2001;50(9):442-448.

63 Sandoval M., Okuhama N.N., Zhang X.J., et al. Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities of cat’s claw (Uncaria tomentosa and Uncaria guianensis) are independent of their alkaloid content. Phytomedicine. 2002;9:325-337.

64 Mur E., Hartig F., Eibl G., et al. Randomised double-blind trial of an extract from the pentacyclic alkaloid-chemotype of Uncaria steoarth for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:656-658.

65 Chrubasik J.E., Roufogalis B.D., Chrubasik S. Evidence of effectiveness of herbal antiinflammatory drugs in the treatment of painful osteoarthritis and chronic low back pain. Phytother Res.. 2007;21:675-683.

66 Gagnier J.J., Chrubasik S., Manheimer E. Harpgophytum procumbens for osteoarthritis and low back pain: a systematic review. BMC Complement Altern Med. 4(13), 2004. Online. Available: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472–6882/4/13 (accessed 14 Oct 2009)

67 Fiebich B.L., Heinrich M., Hiller K.O., et al. Inhibition of TNF-alpha synthesis in LPS-stimulated primary human monocytes by Harpagophytum extract SteiHap 69. Phytomed. 2001;8:28-30.

68 Huang T.H., Tran V.H., Duke R.K., et al. Harpagoside suppresses lipopolysaccharide-induced Inos and COX-2 expression through inhibition of NF-kappa B activation. J Ethnopharmaco. 2006;104:149-155.

69 Chrubasik S., Conradt C., Black A. The quality of clinical trials with Harpagophytum procumbens. Phytomed. 2003;10:613-623.

70 Gagnier J.J., van Tulder M.W., Berman B., et al. Herbal medicine for low back pain: a Cochrane review. Spine. 2007;32:82-92. Review

71 Vlachojannis J., Roufogalis B.D., Chrubasik S. Systematic review on the safety of Harpagophytum preparations for osteoarthritic and low back pain. Phytother Res. 2008;22(2):149-152.

72 Ippoushi K., Azuma K., Ito H., et al. (6)-Gingerol inhibits nitric oxide synthesis in activated J774.1 mouse macrophages and prevents peroxynitrite-induced oxidation and nitration reactions. Life Sci. 2003;73:3427-3437.

73 Thomson M., Al-Qattan K.K., Al-Sawan S.M., et al. The use of ginger (Zingiber officinale Rosc.) as a potential anti-inflammatory and antithrombotic agent. Prostaglandins Leukot Ess Fatty Acids. 2002;67:475-478.

74 Jolad S.D., Lantz R.C., Solyom A.M., et al. Fresh organically grown ginger (Zingiber officinale): composition and effects on LPS-induced PGE2 production. Phytochemistry. 2004;65:1937-1954.

75 Altman R.D., Marcussen K.C. Effects of a ginger extract on knee pain in patients with osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:2531-2538.

76 Bliddal H., Rosetzsky A., Schlichting P., et al. A randomised, placebo-controlled, cross-over study of ginger extracts and ibuprofen in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2000;8:9-12.

77 Zhang B., Li J.B., Zhang D.M., et al. Analgesic and anti-inflammatory activities of a fraction rich in gaultherin isolated from Gaultheria yunnanensis Biol Pharm Bull. 2007;30(3):465-469.

78 Zhang B., He X.L., Ding Y., et al. Gaultherin, a natural salicylate derivative from Gaultheria yunnanensis: towards a better non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;530(1–2):166-171.

79 Chan T.Y. The risk of severe salicylate poisoning following the ingestion of topical medicaments or aspirin. Postgrad Med J. 1996;72:109-112.

80 Ernst E., Chrubasik S. Phyto-anti-inflammatories. A systematic review of randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind trials. Rheum Dis Clin Nort Am. 2000;26:13-27.

81 Ammon H.P. Boswellic acids in chronic inflammatory diseases. Planta Med. 2006;72:1100-1116.

82 Gayathri B., Manjula N., Vinaykumar K.S., et al. Pure compound from Boswellia serrata extract exhibits anti-inflammatory property in human PBMCs and mouse macrophages through inhibition of TNFalpha, IL-1beta, NO and MAP kinases. Int Immunopharmacol. 2007;7(4):473-482.

83 Kimmatkar N., Thawani V., Hingorani L., et al. Efficacy and tolerability of Boswellia serrata extract in treatment of osteoarthritis of knee—a randomised double-blind placebo controlled trial. Phytomedicine. 2003;10:3-7.

84 Sontakke S., Thawani S., Pimpalkhute P., et al. Open, randomised, controlled clinical trial of Boswellia serrata extract as compared to valdecoxib in osteoarthritis of knee. Indian J Pharmacol. 2007;39:27-29.

85 Setty A.R., Sigal L.H. Herbal medications commonly used in the practice of rheumatology: mechanisms of action, efficacy, and side-effects. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2005;34:773-784.

86 Rinsema T.J. One hundred years of aspirin. Med Hist. 1999;43(4):502-507.

87 Rossnagel K., Roll S., Willich S.N. The clinical effectiveness of rosehip powder in patients with osteoarthritis. A systematic review. MMW Fortschr Med. 2007;149:51-56.

88 Chrubasik C., Duke R.K., Chrubasik S. The evidence for clinical efficacy of rose hip and seed: a systematic review. Phytother Res. 2006;20:1-3.

89 Winther K., Apel K., Thamsborg G. A powder made from seeds and shells of a rose-hip subspecies (Rosa canina) reduces symptoms of knee and hip osteoarthritis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Scand J Rheumatol. 2005;34:302-308.

90 Christensen R., Bartels E.M., Altman R.D., et al. Does the hip powder of Rosa canina (rosehip) reduce pain in osteoarthritis patients?–a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008 Sep;16(9):965-972. Epub 2008 Apr 14

91 Grube B., Grünwald J., Krug L., et al. Efficacy of a comfrey root (Symphyti steoa. Radix) extract ointment in the treatment of patients with painful osteoarthritis of the knee: results of a double-blind, randomised, bicenter, placebo-controlled trial. Phytomedicine. 2007;14(1):2-10.

92 Cisár P., Jány R., Waczulíková I., et al. Effect of pine bark extract (Pycnogenol®) on symptoms of knee osteoarthritis. Phytotherapy Research. 2008;22:1087-1092.

93 Mason L., Moore R.A., Derry S., et al. Systematic review of topical capsaicin for the treatment of chronic pain. BMJ. 2004;328:991.

94 Wang Y., Prentice L.F., Vitetta L., et al. The effect of nutritional supplements on osteoarthritis. Altern Med Rev. 2004;9:275-296.

95 Poolsup N., Suthisisang C., Channark P., et al. Glucosamine long-term treatment and the progression of knee osteoarthritis: systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39:1080-1087.

96 Rozendaal R.M., Koes B.W., van Osch G.J., et al. Effect of glucosamine sulfate on hip osteoarthritis: a randomised trial. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(4):268-277.

97 Towheed T.E., Maxwell L., Anastassiades T.P., et al. Glucosamine therapy for treating osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2):2005. CD002946

98 Towheed T.E., Anastassiades T.P., Shea B., et al. Glucosamine therapy for treating osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (1):2001. CD002946. Review

99 Distler J., Anguelouch A. Evidence-based practice: review of clinical evidence on the efficacy of glucosamine and chondroitin in the treatment of osteoarthritis. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2006;18:487-493.

100 Reginster J.Y., Bruyere O., Neuprez A. Current role of glucosamine in the treatment of osteoarthritis. Rheumatology. 2007;46:731-735.

101 Vlad S.C., Lavalley M.P., McAlindon T.E., et al. Glucosamine for pain in osteoarthritis: Why do trial results differ? Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:2267-2277.

102 Clegg D.O., Reda D.J., Harris C.L., et al. Glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate, and the two in combination for painful knee osteoarthritis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(8):795-808.

103 Oliviero U., Sorrentino G.P., De Paola P., et al. Effects of the treatment with Matrix on elderly people with chronic articular degeneration. Drugs Exp Clin Res. 1991;17:45-51.

104 Conrozier T. Anti-arthrosis treatments: efficacy and tolerance of chondroitin sulfates (CS 4 and 6). Presse Med. 1998;27:1862-1865.

105 Uebelhart D., Thonar E.J., Delmas P.D., et al. Effects of oral chondroitin sulfate on the progression of knee osteoarthritis: a pilot study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 1998;6:39-46.

106 Bucsi L., Poor G. Efficacy and tolerability of oral chondroitin sulfate as a symptomatic slow-acting drug for osteoarthritis (SYSADOA) in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 1998;6:31-36.

107 Mazieres B., Combe B., Phan Van A., et al. Chondroitin sulfate in osteoarthritis of the knee: a prospective, double-blind, placebo controlled multicenter clinical study. J Rheumatol. 2001;28:173-181.

108 Morreale P., Manopulo R., Galati M., et al. Comparison of the osteoarthritisry efficacy of chondroitin sulfate and diclofenac sodium in patients with knee osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol. 1996;23:1385-1391.

109 Mathieu P. Radiological progression of internal femoro-tibial osteoarthritis in gonarthrosis. Chondro-protective effect of chondroitin sulfates ACS4-ACS6. Presse Med. 2002;31:1386-1390.

110 Reichenbach S., Sterchi R., Scherer M., et al. Meta-analysis: chondroitin for osteoarthritis of the knee or hip. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:580-590.

111 Kahan A., Uebelhart D., De Vathaire F., et al. Long-term effects of chondroitins 4 and 6 sulfate on knee osteoarthritis: The study on osteoarthritis progression prevention, a two-year, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2009 Jan 29;60(2):524-533. Epub ahead of print

112 Bello A.E., Oesser S. Collagen hydrolysate for the treatment of osteoarthritis and other joint disorders: a review of the literature. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22:2221-2232.

113 Moskowitz R.W. Role of collagen hydrolysate in bone and joint disease. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2000;30:87-99.

114 Adam M. Therapy for osteoarthritis: which effects have preparations of steoart? Therapiewoche. 1991;38:2456-2461.

115 Usha P.R., Naidu M.U.R. Randomised, double-blind, parallel, placebo- controlled study of oral glucosamine, methylsulfonylmethane and their combination in osteoarthritis. Clinical Drug Investigation. 2004;24:353-363.

116 Kim L.S., Axelrod L.J., Howard P., et al. Efficacy of methylsulfonylmethane (MSM) in osteoarthritis pain of the knee: a pilot clinical trial. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006;14:286-294.

117 Soeken K., Lee W.L., Bausell R.B., et al. Safety and efficacy of S-adenosylmethionine (SAMe) for osteoarthritis. J Fam Practice. 2002;5:425-430.

118 Tavoni A., Vitali C., et al. Evaluation of S-adenosylmethionine in primary fibromyalgia. A double-blind cross-over study. Am J Med. 1987;83:107-110.

119 Ameye L.G., Chee W.S. Osteoarthritis and nutrition. From nutraceuticals to functional foods: a systematic review of the scientific evidence. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8:R127.

120 Cobb C.S., Ernst E. Systematic review of a marine nutriceutical supplement in clinical trials for arthritis: the effectiveness of the New Zealand green-lipped mussel Perna canaliculus. Clin Rheumatol. 2006;25:275-284.

121 Cho S.H., Jung Y.B., Seong S.C., et al. Clinical efficacy and safety of Lyprinol, a patented extract from New Zealand green-lipped mussel (Perna Canaliculus) in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip and knee: a multicenter 2-month clinical trial. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;35(6):212-216.

122 Appelboom T., Schuermans J., Verbruggen G., et al. Symptoms modifying effect of avocado/soybean unsaponifiables (ASU) in knee osteoarthritis. A double-blind, prospective, placebo-controlled study. Scand J Rheumat. 2001;30:242-247.

123 Blotman F., Maheu E., Wulwik A., et al. Efficacy and safety of avocado/soybean unsaponifiables in the treatment of symptomatic osteoarthritis of the knee and hip. A prospective, multicenter, three-month, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Rev Rhum Engl Ed. 1997;64:825-834.

124 Maheu E., Mazieres B., Valat J.P., et al. Symptomatic efficacy of avocado/soybean unsaponifiables in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee and hip: a prospective, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter clinical trial with a six-month treatment period and a two-month followup demonstrating a persistent effect. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:81-91.

125 Lequesne M., Maheu E., Cadet C., et al. Structural effect of avocado/soybean unsaponifiables on joint space loss in osteoarthritis of the hip. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;47:50-58.

126 Ernst E. Avocado-soybean unsaponifiables (ASU) for osteoarthritis — a systematic review. Clin Rheumatol. 2003;22:285-288.

127 Little C.V., Parsons T., Logan S. Herbal therapy for treating osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 1):2001. Art no CD002947

128 Harmer A.R., Naylor J.M., Crosbie J., et al. Land-based versus water-based rehabilitation following total knee replacement: A randomised, single-blind trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2009 Jan 29;61(2):184-191. Epub ahead of print

129 Manheimer E., Linde K., Lao L., et al. Meta-analysis: acupuncture for osteoarthritis of the knee. Ann Int Med. 2007;146:868-877.

130 White A., Foster N.E., Cummings M., et al. Acupuncture treatment for chronic knee pain: a systematic review. Rheumatology. 2007;46:384-390.

131 Kwon Y.D., Pittler M.H., Ernst E. Acupuncture for peripheral joint osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology. 2006;45:1331-1337.

132 Hulme J., Robinson V., DeBie R., et al. Electromagnetic fields for the treatment of osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (1):2002. CD003523

133 Brosseau L., Welch V., Wells G., et al. Low level laser therapy (Classes I, II and III) for treating osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (3):2004. CD002046

134 Bjordal J.M., Johnson M.I., Lopes-Martins R.A., et al. Short-term efficacy of physical interventions in osteoarthritic knee pain. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised placebo-controlled trials. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2007;8:51.

135 Eckes Peck S.D. The effectiveness of therapeutic touch for decreasing pain in elders with degenerative arthritis. J Holist Nurs. 1997;15:176-198.

25

25