CHAPTER 27 Os Acromiale

PREOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS

Os acromiale is an uncommon anatomic anomaly that can be implicated in symptoms of rotator cuff pathology. It was recognized as an anatomic anomaly over 140 years ago,1 but its relevance in shoulder pathology and its treatment remain a point of controversy. The reported incidence of os acromiale varies from 1.5% to 15% in the population,2–4 but the incidence of os acromiale has not been noted to be higher in patients with impingement or rotator cuff disease. Does the presence of an os acromiale create a disadvantageous biomechanical situation that leads to impingement and rotator cuff tears? Regardless of the incidence of os acromiale in rotator cuff pathology, the surgeon is bound to encounter this association and will be faced with a surgical decision. An open fusion of the os acromiale with internal fixation can restore normal acromial anatomy and avoid the deltoid dysfunction produced by the open excision of large fragments,5–7 but the advent of arthroscopic management of impingement and rotator cuff tears has produced a new paradigm for the surgeon. Open reduction and internal fixation may be able to preserve these large fragments, but not without significant morbidity, the risk of nonunion, and the frequent need for hardware removal. It is difficult to resort to the open treatment of impingement and rotator cuff tears when arthroscopic subacromial decompression and arthroscopic rotator cuff repair are now the new standard of care in the treatment of rotator cuff disease. When an os acromiale is diagnosed in conjunction with rotator cuff disease, the arthroscopic resection or near-complete resection of the os has been shown to be effective, without any deleterious effect on the deltoid.8,9

ANATOMY AND PATHOANATOMY

Os acromiale is the result of failure of fusion of the acromiale apophyses. The resulting failure can produce two distinct physiologic types of os acromiales, a synchondrosis with a nonmobile os or pseudoarthrosis with a mobile os. The former is stable and does not require operative treatment; the latter is unstable, with a resulting step-off, and is cause for concern in the presence of impingement and/or rotator cuff tears.7 The pseudoarthrosis can be hypertrophic, presenting an irregular inferior surface to the rotator cuff.

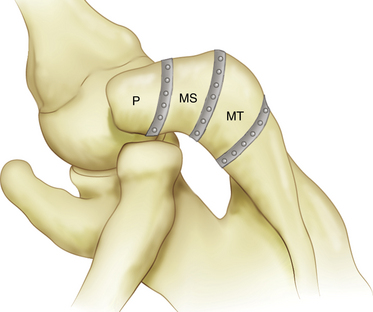

Three ossification centers of the acromion appear between the ages of 15 and 18 years and fuse with the scapula between the ages of 22 and 25 years.9 There are three potential areas of nonunion and thus three types of os acromiales (Fig. 27-1), but there is lack of agreement on the location of these areas of nonunion. The preacromion is the smallest of the os and its posterior margin is located at or anterior to the midpoint of the distal clavicle. The mesoacromion is defined by its posterior margin, which is in line with the posterior margin of the clavicle and acromioclavicular joint. The meta-acromion is the largest of the os and its posterior margin is located close to the lateral aspect of the scapular spine.8,10 The mesoacromion is the most common and is the primary subject of discussion. The preacromion is the next most frequently encountered and its excision is without consequence. The meta-acromion is uncommon, but the incidence and occurrence of these different types are uncertain. There is considerable variability in the location of the pseudoarthrosis site, which can occur anywhere within the developing acromion, so how each author defines the types of os acromiales treated also varies.4–9

DIAGNOSTIC IMAGING

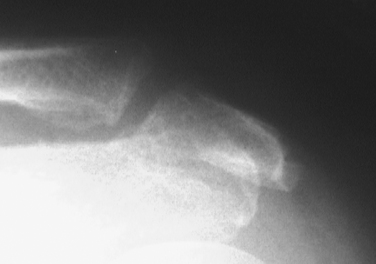

Os acromiale is readily visualized on standard radiographs, as well as on computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans. An anteroposterior (AP) x-ray view demonstrates a double contour because the os is superimposed over the remaining posterior acromial bone (Fig. 27-2). Outlet and axillary x-ray views can also show the os. MRI better defines the os and can also demonstrate the status of the underlying cuff. Os acromiale is best seen on MRI axial views (Fig. 27-3).

INDICATIONS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS

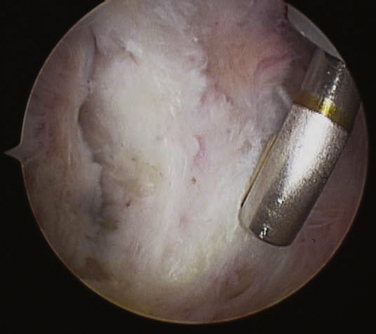

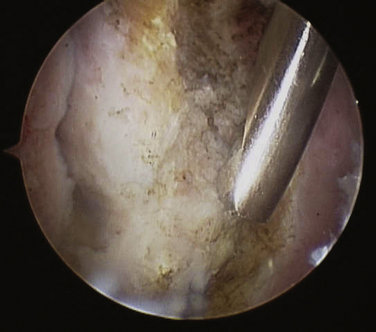

The indication for surgical treatment of os acromiale depends on the associated pathology and size of the os. The presence of the mobile os acromiale associated with impingement and/or rotator cuff tears produces special surgical considerations for the os, in addition to the treatment for the cuff. It had been previously thought that the mobile os produced impingement when contraction of the deltoid attached to the os pulled it inferiorly.11 More recently it has been postulated that it is the upward mobility of the os that produces a step-off with the remaining acromion.7 Although there is little evidence that os acromiale is more prevalent in patients with rotator cuff tears, the surgeon who encounters a large mobile fragment has a decision to make. One could opt to perform an acromioplasty on the os, but that leaves a potentially unstable fragment that can remain symptomatic and require secondary surgery.12 A more complete arthroscopic resection using a burr resects the os, yet leaves the periosteum, coracoacromial ligament, and deltoid intact (Fig. 27-4).

FIGURE 27-4 A more complete arthroscopic excision via burring removes the os, yet leaves the periosteum, coracoacromial ligament, and deltoid intact. The patient is in the lateral decubitus position, with the scope in the posterior portal. The burr is in the midlateral portal, as seen in Figure 27-6.

Open fusion of the os acromiale with cannulated screws, tension band wiring and bone grafting can produce good results,5,7,13 but the procedure comports significant morbidity, a lengthy recovery period, the potential for nonunion, and secondary procedures to remove hardware. This approach should be considered for young patients with large os acromiales and/or those involved in competitive sports with high shoulder demands.

The only contraindication for the treatment of os acromiale is the open excision of an os acromiale. The literature is replete with caution regarding the open excision of a large os, but with basic arthroscopic instruments and techniques, resection of a large os can be achieved without any deltoid compromise.5,8,11

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Conservative Treatment

Nonoperative treatment of os acromiale is that of impingement and rotator cuff disease. Activity modification, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and subacromial corticosteroid injections are the mainstays of conservative care.

Operative Treatment

There is little debate over the treatment of a small preacromiale os. Excision is the generally accepted approach. Controversy arises concerning the treatment of large mobile os acromiales. When encountered in the open treatment of impingement and rotator cuff tears, it was rapidly noted that the open excision of a large os produced deltoid defects and dysfunction.11 In an effort to avoid those complications, meso– and meta–os acromiales have been treated primarily with open reduction and internal fixation.5-7,11,13 The approach became a necessity when it became apparent that the open excision of large os acromiales resulted in the loss of deltoid function and produced poor results.11 Cannulated screws and tension band wiring provide excellent internal fixation, but can be technically challenging to implant because the acromial fragments that can be thin and fragile. With the improvements in fixation, the risks of nonunion have been reduced, but not eliminated.5 Secondary operations for hardware removal are often necessary in patients in whom solid fusion was obtained.

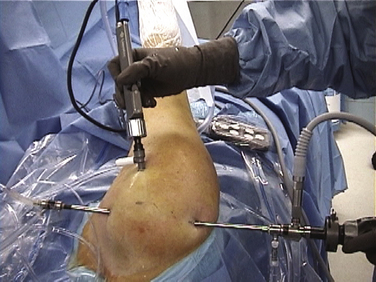

Arthroscopic subacromial decompression with complete or nearly complete resection of the unstable mesoacromion can be performed without complications and is an acceptable approach in cases of impingement and os acromiale.8,9 The arthroscopic resection of the os is an extended arthroscopic subacromial decompression. This is a technically simple procedure with minimal equipment needs. The technique can be performed in the beach chair or lateral decubitus position. The arthroscope is placed in the standard posterior portal, and a radiofrequency (RF) device is placed in a midlateral portal to remove any soft tissues from the undersurface of the os, the nonunion, and residual acromion (Fig. 27-5). The burr is placed in the midlateral portal to access the os (Fig. 27-6). The burr is used to resect the os, but care is taken to preserve the periosteal and soft tissue envelope of the os (Figs. 27-7 and 27-8). Leaving a few bone islands in the soft tissue envelop is recommended to ensure continuity of the envelope. An effort is also made to remove and residual osteophytes from the remaining acromion. Chamfering is performed on the residual anterior acromial margin.

PEARLS& PITFALLS

CONCLUSIONS

The treatment of os acromiale has evolved with the treatment of impingement and rotator cuff disease. In the years prior to arthroscopic management of impingement and rotator cuff tears, surgeons noted that the open excision of large os acromiales would lead to defects in the deltoid, with resulting deltoid dysfunction. Subsequently, all efforts were made to preserve the deltoid by fusing the os to the remaining acromion. The techniques of open reduction, internal fixation, and bone grafting have been improved, and the nonunion rate has been reduced but not eliminated. The morbidity, complications, and extended recovery time for open reduction and internal fixation are difficult to justify in an era when arthroscopic treatment of impingement and rotator cuff tears has become the standard of care. There is sufficient evidence,8,9 supported by my experience, to recommend arthroscopic resection for symptomatic mobile os acromiale in association with impingement and rotator cuff tears.

1. Gruber W. Uber die Arten der Acromialknochen and accidentellen Acromialgelenke. Arch Anat Physiol Wissensch Med.. 1863:373-387.

2. Macalister A. Notes on the acromion. J Anat Physiol. 1893;27:245-251.

3. Liberson F Os acromiale: a contested anomaly. J Bone Joint Surg, 19; 1937:683-689.

4. Sammarco VJ Os acromiale: frequency anatomy and clinical implications. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 82; 2000:394-400.

5. Warner JJ, Beim GM, Higgins L. The treatment of symptomatic os acromiale. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80:1320-1326.

6. Boehm TD, Matzer M, Brazda D, Gohlke FE Os acromiale associated with tear of the rotator cuff treated operatively: review of 33 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br, 85; 2003:545-549.

7. Peckett WR, Gunther SB, Harper GD, et al Internal fixation of symptomatic os acromiale: a series of twenty-six cases. J Shoulder Elbow Surg, 13; 2004:381-385.

8. Ortiguera CJ, Buss DD. Surgical management of the symptomatic os acromiale. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11:521-528.

9. Wright RW, Heller MA, Quick DC, Buss DD. Arthroscopic decompression for impingement syndrome secondary to an unstable os acromiale. Arthroscopy. 2000;16:595-599.

10. Lee DH, Lee KH, Lopez-Ben R, Bradley EL The double-density sign: a radiographic finding suggestive of an os acromiale. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 86-A; 2004:2666-2670.

11. Neer CS. Rotator cuff tears associated with os acromiale. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66:1320-1321.

12. Hutchinson MR, Veenstra MA. Arthroscopic decompression of shoulder impingement secondary to os acromiale. Arthroscopy. 1993;9:28-32.

13. Ryu RKN, Fan RSP, Dunbar WHV. The treatment of symptomatic os acromiale. Orthopedics. 1999;22:325-328.