23

Orthopedic Management of the Wrist and Hand

1. Identify and describe a common compression neuropathy of the wrist.

2. Discuss methods of management and rehabilitation of compression neuropathy of the wrist.

3. Identify and describe common ligament injuries of the wrist.

4. Describe and discuss methods of management and rehabilitation of ligament injuries of the wrist.

5. Describe methods of management and rehabilitation for distal radial and ulnar fractures.

6. Identify methods of management and rehabilitation for scaphoid fractures.

7. Identify and describe common metacarpal and phalanx fractures and methods of management and rehabilitation.

8. Describe methods of management and rehabilitation following surgery for Dupuytren’s disease.

9. Identify and describe common extensor and flexor tendon injuries.

10. Discuss methods of management and rehabilitation of extensor tendon and flexor tendon injuries.

11. Identify methods of management and rehabilitation for complex regional pain syndrome.

BONY INJURIES OF THE WRIST AND HAND

1. The number of fragments in the fracture

2. The fragment orientation (displaced or in alignment)

3. The approach used to restore anatomic alignment (closed reduction or open reduction)

4. The method used to maintain the reduction (external fixation: casts, splints; internal fixation: pins, screws, or plates; or percutaneous fixation: pins that protrude through the skin into the bone)

Distal Radial and Ulnar Fractures

Radius

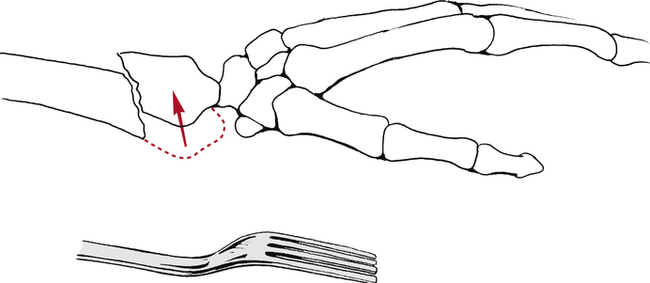

The most common distal radius fractures are Colles fractures.10 A Colles’ fracture is defined as a radius fracture within 2.5 cm of the wrist in which the distal fragment is displaced in a dorsal direction.10 This is also known as a dinner fork deformity due to the resemblance resulting from the shape of the wrist and hand following this fracture (Fig. 23-1). This injury is usually the result of a fall on the palm of an outstretched hand. Treatment of these common fractures is controversial and more than 85% require reduction.10

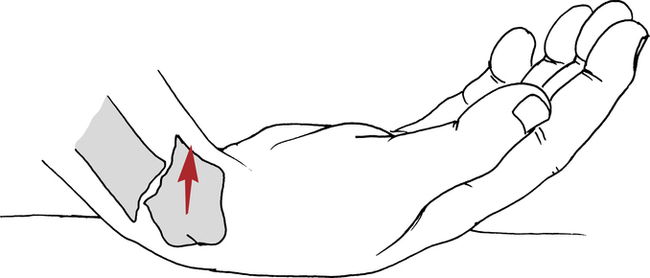

A Smith fracture is also referred to as a reverse Colles fracture.10 The fracture usually occurs from a fall on the dorsum of the hand, with the resultant distal radial fragment displaced in a palmar direction (Fig. 23-2). The course of treatment is similar to the Colles fracture and the rehabilitation is the same.

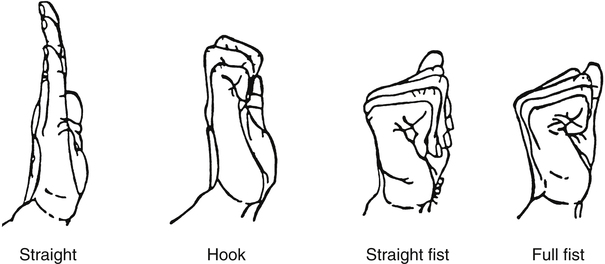

Rehabilitation starts as soon as stable immobilization has been achieved. The goals are to reduce edema through positioning and retrograde massage and to maintain digit ROM through exercise. The distal edge of the cast or splint must be proximal to the distal palmar crease in order to allow full flexion of the metacarpal phalangeal (MP) joints. “Six-pack” exercises are taught and performed hourly while awake (Fig. 23-3).6 These exercises maintain MP and interphalangeal (IP) ligament length and encourage differential gliding of the finger and wrist tendons. Passive assistance may be needed to achieve full range. Light gripping, pinching, and using the fingers is encouraged as long as there is no pain at the fracture site. Active forearm rotation within the limit of the cast should also be started. Shoulder pain should be evaluated further by the PT as proximal injuries can be overlooked in light of the distal radius fracture.

Some distal radius fractures require immobilization of the elbow to prevent forearm rotation for the first 3 weeks.26 Once the cast is modified to free the elbow, active and passive exercise to the elbow can begin. The PT should be consulted before beginning resisted elbow flexion because of the attachment of the brachioradialis on the radial styloid. Strong contractions of this muscle may cause a loss of the fracture reduction.26 Complications following distal radial fractures include: loss of reduction of the fracture fragments, nonunion (the break does not heal), malunion (partial healing or poor alignment), tendon adhesions, median nerve compression, instability, Volkmann ischemic contracture, and complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS).10 The patient’s pain, circulation and sensation should be monitored during each session and the exercises should be adjusted accordingly.

When the cast is discontinued, the patient may be placed in a soft splint between exercise sessions until the wrist muscles are stronger. Active and active assisted ROM to the wrist and forearm are initiated, making sure combinations of motion, such as flexion and ulnar deviation, are performed. Patients should be taught to isolate the wrist muscles from the finger muscles as they will have a tendency to lead wrist motion with the finger muscles. Encouraging the patient to hold a paper towel core while moving the wrist helps to accomplish this without adding resistance. Submaximal isometric exercises at various positions in the range are also started. Modalities to increase tissue extensibility or relieve pain are initiated as long as edema remains controlled. Strengthening is usually started 4 to 5 weeks after cast removal. The physician will order this only if the fracture site is no longer tender to palpation and evidence of bony union is seen. Closed-chain weight bearing is also gradually started at this time. Joint mobilization can be helpful in regaining full ROM. Patients generally return to work without restrictions about 10 weeks after cast removal.26

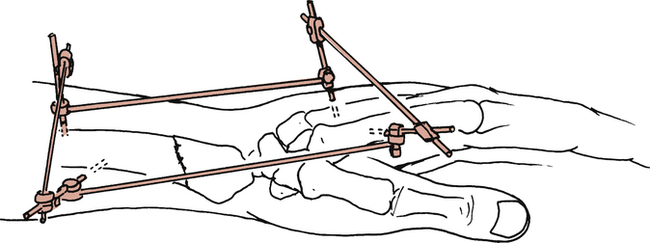

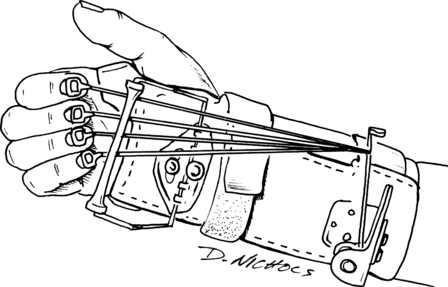

Patients with percutaneous fixation (sometimes called external fixators) can often follow the same exercise program outlined earlier (Fig. 23-4). The fixator stays in place until radiographs reveal evidence of bony healing, generally in 6 weeks.6

Distal Ulna Fractures

Fractures of the distal ulna usually occur in combination with distal radius fractures.20 The medical management and rehabilitation follow the guidelines outlined above. Persistent pain with rotation or weight bearing suggests further evaluation of the triangular fibrocartilage complex is necessary to rule out tears (see later discussion).

Scaphoid Fractures

A scaphoid fracture is often the result of a minor fall on the palm with the wrist hyperextended and radially deviated.1 It is often dismissed as a sprain, delaying treatment. Pain and swelling in the area of the anatomic snuffbox that do not resolve over a few weeks, pain with wrist extension, and decreased grip strength are signs indicating further evaluation is needed.

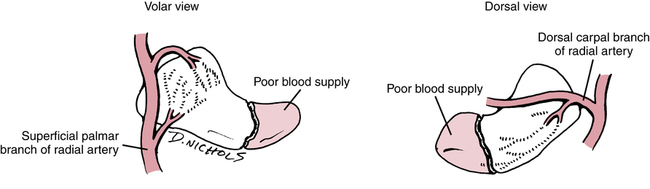

The location of the fracture within the scaphoid determines the method of treatment. The blood supply to this bone enters distally, leaving the proximal portion without direct circulation when it is separated by a fracture (Fig. 23-5). Fractures in the proximal third of the bone have a high incidence of nonunion, and those that do heal take much longer, anywhere from 12 to 24 weeks of immobilization compared with 5 to 6 weeks for the distal portion.1,4 Fractures that are not displaced or can easily be reduced are immobilized in a thumb spica cast. Nonreducible fractures require internal fixation with rigid immobilization. If nonunion and avascular necrosis (AVN) occur, bone grafts from the distal radius may be necessary.4

Rehabilitation should begin during immobilization as described under distal radial fractures. Edema reduction and ROM of the uninvolved distal joints are the primary focus. Following cast removal, the patient usually wears a thumb spica splint between exercise sessions. Wrist exercises should focus on differential gliding of the wrist and finger muscles. Strengthening with exercise putty, sustained grip activities, and gradual closed-chain activities progress to tolerance. Patients usually return to full activity within 12 weeks after cast removal.4 If the patient is having difficulty regaining motion, static progressive splinting, dynamic splinting, and joint mobilization can help restore full range.

Metacarpal Fractures

Fractures of the metacarpals can occur in the base, shaft, neck, or head. These are due to falls, jammed fingers, or direct blows.29 Fractures that are nondisplaced or minimally displaced are placed in a cast or splint for 3 to 4 weeks, usually including the joint above and the joint below the fracture.30 The MP joint is placed in 45° to 60° of flexion to prevent collateral ligament shortening. Displaced fractures require surgical intervention and fixation by open or percutaneous techniques.

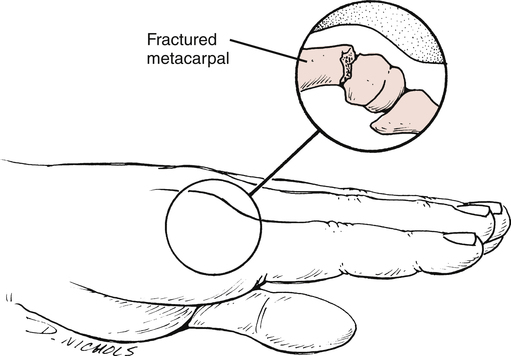

Fractures of the neck of the fourth or fifth metacarpal are called boxer’s fractures (Fig. 23-6). These occur when the patient strikes a hard object with a clenched fist. Ironically, these are rarely seen in professional boxers.30 These patients are immobilized with the wrist in slight extension and the MP joint flexed for 3 to 4 weeks.29,30 The proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints are free to flex and extend often within 24 hours. Edema control sometimes requires the use of an isotoner glove as well as massage and elevation.

Active range of motion (AROM) should emphasize isolated extensor digitorum communis motion, MP flexion, and composite flexion. Tendon adhesions to the fracture site or, in the case of open procedures, the skin, often limit gliding of the extensor tendons. A splint should be worn in between exercise sessions for an additional 2 weeks. At 6 weeks, passive ROM and resistance can be started emphasizing interossei strengthening in order to achieve full IP extension.19 If the fixation is less stable, ROM may be delayed until 3 to 4 weeks, then follow the course outlined previously. When the incision has healed, scar mobilization techniques should be started.

Bennett fracture is a fracture of the palmar base of the proximal first metacarpal.30 The ligaments hold the fragment in place, but the remainder of the base is pulled radially and dorsally, resulting in a fracture-dislocation.30 As with a boxer’s fracture, treatment can be with closed reduction and rigid cast immobilization or with an open reduction with internal fixation (ORIF) procedure, depending on the severity of the fracture. There must be nondisplaced solid union at the fracture site before active motion can begin. If closed reduction is used, immobilization lasts 6 weeks to promote stable union.30 If an ORIF procedure is used, immobilization is slightly shorter because of the rigid internal fixation. Rehabilitation closely parallels the treatment for a boxer’s fracture with emphasis on regaining the thumb web space, opposition and composite flexion and extension. Resisted exercise, pinch, grip, and weight bearing on the palm with the thumb abducted can progress when stable fracture healing has occurred.

Phalanx Fractures

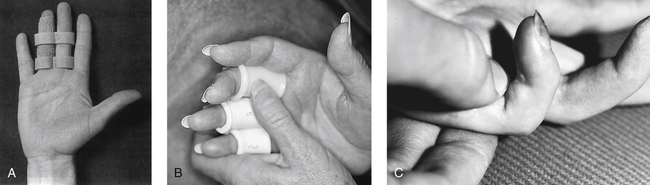

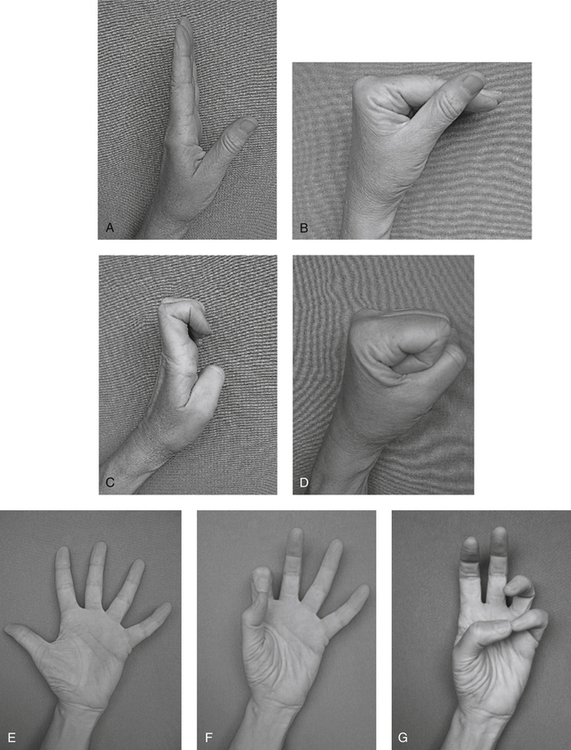

Phalanx fractures can occur at the neck, shaft, or base of the phalanx. Stable, closed, nondisplaced fractures are treated by buddy taping (Fig. 23-7, A) or with simple splints and immediate active ROM. More complex closed proximal and middle phalanx fractures should be placed in a hand-based splint for 3 to 4 weeks.24 This splint should hold the MP joints in 50° to 70° flexion and the IP joints in 10° to 15° of flexion.24 Once radiographic evidence of healing is confirmed, ROM can progress. The most common complication is loss of PIP joint extension.9 Blocking exercises can help prevent the tendons from adhering to the fracture site (Fig. 23-7, B, C).

The distal phalanx is the most frequently fractured bone in the hand.21 These fractures are usually splinted in extension using a small aluminum splint leaving the PIP joint free. Isolated PIP motion and MP motion can be started immediately. Often the nail bed is injured, leaving the finger hypersensitive and stiff. These patients are started on a program of desensitization, using touching, tapping, fluidotherapy, and vibration to overcome the hypersensitivity. Once movement can begin at the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint, (usually at 3 weeks), the emphasis is on composite digit flexion and coordinated use of the digits. Patients often bypass the injured digit in functional activities, so this is addressed in therapy with buddy taping, light grasping, and pinching exercises that isolate the thumb and the involved finger. If the terminal extensor tendon is disrupted (see “Mallet Finger” section), the DIP joint is splinted for 6 to 8 weeks. Aggressive passive flexion should be avoided because it may lead to an extensor lag.21

SOFT TISSUE INJURIES OF THE WRIST AND HAND

Ligament Injuries of the Wrist

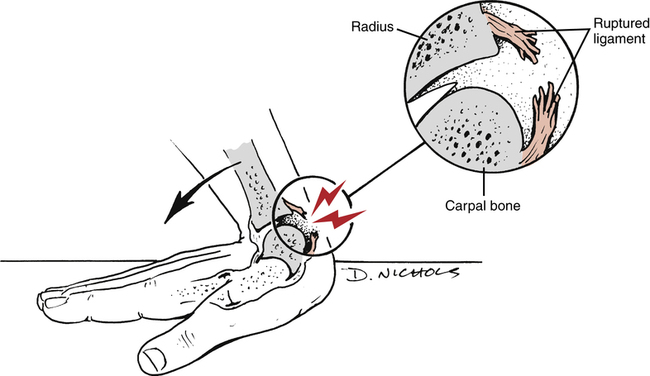

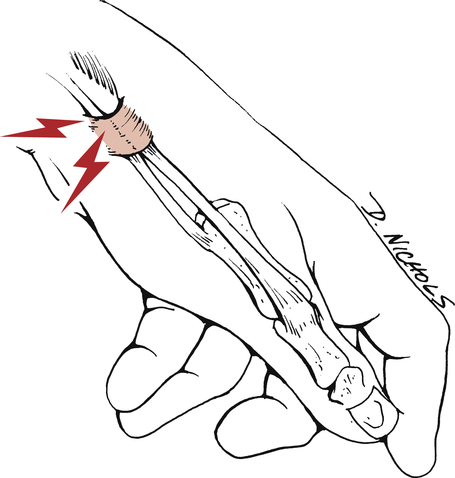

Stability of the wrist depends primarily on intracapsular ligaments and not on intrinsic dynamic support from musculotendinous tissue.34 Ligament sprains with varying degrees of carpal instability usually result from a fall with the wrist hyperextended (Fig. 23-8).34

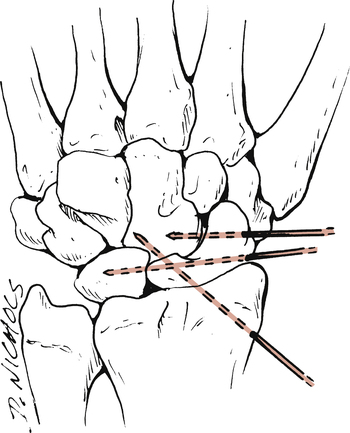

Partial ligament injuries without carpal instability are immobilized in a short arm cast or splint for 3 to 4 weeks. Severe ligament injuries lead to carpal instability and reduction and maintenance of the alignment are more difficult. Options include rigid cast immobilization, closed reduction with percutaneous pinning, and ORIF (Fig. 23-9).34 If cast immobilization is used to stabilize the joint, the patient is placed in the cast for 6 to 12 weeks, depending on the severity of the injury.34 If closed reduction and internal fixation is required, the wrist is immobilized for about 2 months. After two months, the pins are removed, and the arm is placed in a cast for an additional 4 weeks.34 With an ORIF procedure, the ligaments are directly repaired and the unstable carpal articulations are stabilized with wires or pins. The duration of immobilization is similar to that for closed reduction with percutaneous pinning.34

Regardless of the severity of the injury, the principles for rehabilitation are the same.10 The initial goals are to control pain and inflammation through the use of cold and electrical stimulation and to prevent edema through elevation, massage, light external compression wraps, and frequent digit active ROM within the limits of the immobilization. When the immobilization is removed, gentle, active, pain-free motion can begin in all planes. It is important to include forearm rotation and differential tendon glides between the wrist and fingers. As motion improves and pain subsides, submaximal isometric contractions can be used, progressing to resistance exercises and gradual closed-chain exercises. The last step is to gradually increase the speed of movement. Exercising with a metronome is helpful. Sustained gripping and concentric and eccentric exercises improve wrist strength. Protection of the wrist continues well into the final recovery stages of rehabilitation and the use of a wrist splint is encouraged in between exercise sessions.

Triangular Fibrocartilage Complex

Pain in the ulnar side of the wrist may indicate an injury to the triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC). The TFCC is formed by ligaments and an articular disk between the ulna and the ulnar carpal bones.16 Injury to the TFCC can occur from an axial force applied to the ulnar side of the wrist during weight bearing and gripping (as in gymnastics) or a fall on the palm with the forearm pronated. The ulna is longer compared with the radius when the forearm is pronated.16 This can lead to an ulnocarpal impaction syndrome that results in a torn articular disk and damage to the ulnar head and lunate. Distal radial fractures resulting in a loss of radial length can also leave the ulna longer than the radius. The central disc of the complex has poor blood supply so healing tears in it is difficult.38 Treatment initially involves rest and splinting of the wrist and elbow to prevent forearm rotation for 4 to 6 weeks, then a gradual program of ROM exercises and progressive strengthening.38 Exercises should begin in supination, then progress to neutral, with pronated gripping and weight bearing being the final stage.16 If the symptoms are not relieved by conservative methods, arthroscopic débridement or ulnar shortening are considered.38

Skier’s Thumb

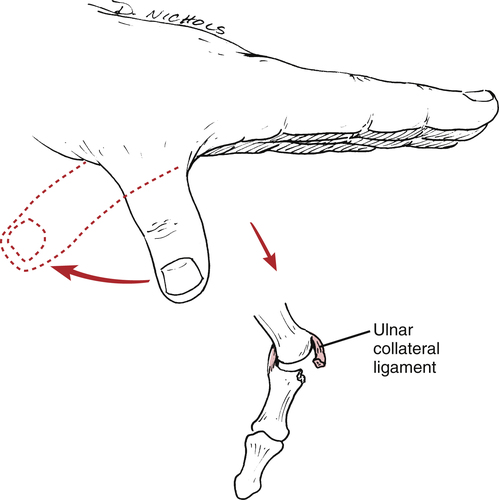

Skier’s thumb is an acute sprain of the ulnar collateral ligament of the thumb. The mechanism of injury is a sudden valgus stress and hyperextension of the thumb, which results in either a partial ligament tear or a complete rupture (Fig. 23-10).35

Partially torn ligaments can be treated nonsurgically with a thumb spica cast or rigid immobilization. The thumb carpal metacarpal (CMC) joint is abducted to 30° and the IP joint is left free for exercise. The splint is worn continuously for 3 to 4 weeks.11,38 Edema reduction techniques are used as needed. At 3 to 4 weeks, the splint can be removed for active thumb MP and composite CMC, MP, and IP joint motion. Progressive strengthening can begin at 5 to 6 weeks and the protective splint is decreased except for heavy activities. Unrestricted use is delayed until 3 months postinjury.

Complete injuries may require surgery because they can be associated with a fracture of the proximal phalanx, or the distal end of the ligament may be displaced by the adductor muscle insertion preventing healing (Stener lesion).11,38 A short arm thumb spica cast is applied for approximately 4 weeks.35 The IP joint is left free and active flexion and extension is started immediately to prevent adherence of the extrinsic tendons. At 4 weeks, the cast is replaced by a splint and the program progresses as discussed earlier except strengthening, which should be cleared by the surgeon—usually at about 6 weeks. Scar massage and nightly application of silicon to the scar should help flexibility. The goal is a pain-free, stable thumb with pinch and grip values comparable to the uninjured hand. Unrestricted use is permitted around 3 month postsurgery.1

De Quervain Disease

De Quervain disease is a condition affecting the abductor pollicis longus and the extensor pollicis brevis tendons and sheaths (Fig. 23-11).36 These tendons comprise the first dorsal extensor compartment and pass through a fibro-osseous tunnel lined with synovium between the distal radius and the extensor retinaculum. Repeated tension, such as that from simultaneous abduction and extension of the thumb and medial and lateral deviation and extension of the wrist, creates friction that can lead to swelling and thickening of the connective tissue and narrowing of the tunnel.13,36 While many sources describe the process as a tendinitis, or an inflammation of the tendon, or tenosynovitis, an inflammation of the sheath, others dispute this finding and refer to it as a tendinosis or degeneration of the tendon cells and collagen.2

The disease presents as pain on the radial side of the wrist that is aggravated by use of the thumb. Swelling and, in some cases, nodules may be palpable. Pain is increased by ulnar deviation of the wrist when the thumb is clasped in the palm (Finkelstein test)13,36 It is a cumulative trauma disorder frequently caused by overuse of the hand and wrist.13

Traditional conservative management includes activity modification aimed at avoiding the provocative motions and/or wrist and thumb immobilization. In addition, ice and high voltage, pulsed, galvanic electrical stimulation (HVPGS) may help symptoms. Iontophoresis is frequently ordered, but its effectiveness has not been established.2 Passive motion in the pain-free range of the wrist and thumb should be done daily and progression to active motion can begin as tolerated. Strengthening can be initiated once active ROM is pain free and should emphasize eccentric as well as concentric motions of the wrist and thumb. All muscles of both thumbs should be strengthened because they have been shown to be weak compared with normal individuals.8 The speed of ROM should gradually be increased as the final step in rehabilitation. Patients should be prepared for a recovery time of months rather than weeks.2

Tendon Injuries

Extensor Tendon Injuries

Injuries to the extensor tendons are often treated as trivial, but they require careful management to maintain the dynamic balance of the fingers and wrist. Extensor muscles are weaker than the flexors so restoration of strength is important. On the back of the hand, these tendons are superficial and have a large surface area that makes them susceptible to injury and adhesions.27 An in-depth discussion of all levels of injury and methods of repair is beyond the scope of this text, but two of the more common injuries are discussed below. The PTA should follow the PT’s instructions precisely when working with an extensor tendon repair.

Mallet finger

Interruption of the extensor tendon mechanism over the DIP joint (zone 1) is referred to as a mallet finger. These injuries can be purely tendon or can include a fracture of the distal phalanx (Fig. 23-12). The imbalance that is created by the unopposed force of the flexor digitorum profundus muscle, positions the DIP joint in flexion and, with time, may lead to hyperextension of the PIP, resulting in a “swan neck deformity”27 With either tendon rupture or avulsion fracture, the treatment is the same. The recommended treatment of a closed injury is continuous, uninterrupted splinting of the DIP joint for 6 weeks in hyperextension with the PIP joint free. The splint may require modification as swelling subsides, but care should be taken to not allow the DIP to change position during the adjustment. Active flexion and extension of the PIP joint begins immediately, but the adjacent finger DIP joints are not actively exercised. At 6 weeks, active flexion of the DIP joints begins. Initially, only 20° of flexion is allowed. The extension splint is reapplied at night for 4 more weeks. The patient is advised against using a strong muscle effort, and passive flexion is contraindicated. The flexion angle is increased each week as long as full extension is maintained. Full active flexion is delayed until at least 3 months postinjury. If an extension lag develops, full-time splinting is resumed.5,27

Boutonnière deformity

Interruption of the central tendon and triangular ligament at the PIP joint (zone III) allows the head of the proximal phalanx to herniate dorsally resulting in a boutonnière deformity (Fig. 23-13).27 This displacement leads to imbalance between the intrinsic and extrinsic muscles of the finger. The resultant position of the finger is flexion of the PIP joint and hyperextension of the DIP. If the deformity can be corrected passively, the finger is held in full PIP extension for 6 weeks with the MP and DIP joints free. The goal is to approximate the ends of the tendon so they can heal together. The PTA should alert the PT if swelling decreases and the splint or cast is loose, requiring remolding. Active and passive DIP flexion is encouraged. After 6 weeks, active motion of the PIP is initiated but the digit is splinted in between sessions for 2 to 4 weeks. Just as with the mallet finger, the patient gradually increases active flexion of the PIP joint. The splint is gradually decreased as long as full PIP extension is maintained. The patient should be warned that treatment may be required for 6 to 9 months.27

Flexor Tendon Injuries

As with extensor tendons, the flexor tendons are classified into zones. The most difficult is zone 2, which extends from the level of the MP joints to the insertion of the flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) just distal to the PIP joint. Injuries in this zone may involve both the FDS and the FDP tendons.31

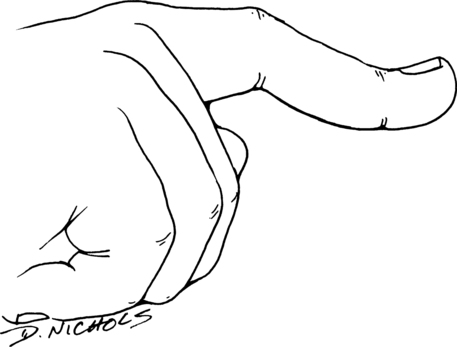

There are presently three approaches to flexor tendon rehabilitation and the choice depends on the factors listed earlier as well as the patient’s ability to comply.31 In all of the methods, the flexor tendon is held on slack with wrist flexion, the MP joints flexed, and the IP joints allowed full extension.

1. Immobilization: Following repair, the wrist and hand are casted or splinted for 3 to 4 weeks before beginning active and passive exercise. This is generally reserved for children or adults who are unable to cooperate in their care.

2. Early passive mobilization: Passive flexion and active extension are allowed within the limits of the splint. Rubber band traction is sometimes used to pull the fingers passively into flexion (Fig. 23-14).

3. Early active mobilization: With these programs, the tendon is moved actively within 48 hours of repair and within carefully outlined limits set by the surgeon. These programs are only for the most compliant patient who can attend therapy frequently.

The splint is worn for about 4 weeks. After the initial 4 weeks, it may be modified to move the wrist into neutral and active motion is progressed. Specific progression to isolated joint motion or passive extension should be discussed in detail with the PT and surgeon.

Strengthening is initiated at about 8 weeks and the patient is generally informed that return to full, unrestricted use will take 3 months at a minimum.31 If the tendon becomes adherent and cannot glide, surgery will be considered to free the tendon from the scar.

Dupuytren Disease

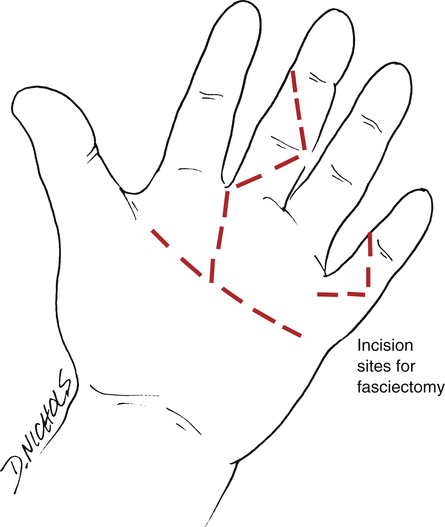

Dupuytren disease in the hand is first observed with the formation of pits and firm nodules that lie just below the skin of the palm (Fig. 23-15).18 The nodules can be composed of overactive fibroblasts producing collagen or can be from “bunching” of the skin in response to a longitudinal contraction of the underlying fascia.18 This tissue is not random, but appears along longitudinal tension lines in the palm or digits. The tissue undergoes contraction and maturation resembling that of normal wound healing. There is no known “trigger” but the tissue becomes thicker and eventually forms cords that become firm and tendon-like and the affected digits and thumb lose extension. The progression is variable and will be limited to nodules in some patients or progress to full flexion of the affected digits in others. Patients may report some tenderness with pressure on the nodules but pain is not a primary complaint. The greatest incidence is in white males of northern European descent, although it has been reported in all races and both sexes.28 Initially, treatment is centered on patient reassurance and education. Reported conservative treatment includes the injection of steroids that may soften the nodules or collagenases, which are chemicals known to break down collagen.3

Once the disease interferes with function, a surgeon should be consulted. There is disagreement regarding the best surgical approach for treatment, but there are four main techniques currently in the literature.17 They are:

1. Fasciotomy: cutting the contracted fascia blindly by inserting a small blade

2. Regional fasciectomy: removal of only the diseased fascia (Fig. 23-16)

3. Extensive fasciectomy: removal of the diseased tissue and any tissue with the potential of becoming diseased

4. Dermofasciectomy: removal of the skin overlying the diseased tissue as well as the diseased tissue. This is replaced by a full thickness skin graft or in some cases, left open to granulate in.

Immediately after surgical release, the patient is fitted with a dorsal blocking splint that allows active flexion but limits full extension at the MP joints.5,23 This splint is used for the first 2 to 3 weeks to avoid tension and vascular compromise in the healing incisions. Static, volar extension splints can be added at 10 days. After the incisions have closed, the dorsal splint is replaced by a hand-based volar splint that holds MPs as well as the IP joints in the full available extension. This splint is worn an average of 3 months postoperatively at night and for short periods during the day, depending on the patient’s ability to maintain the extension during wound and scar maturation. The CHT designs, fabricates, and adjusts the splints. The PTA should check the fit at each visit and alert the CHT when volume changes or improvements in the ROM necessitate splint adjustment. Wound care may include use of the whirlpool to loosen devitalized tissue, but care should be taken to avoid a completely dependent position because of edema concerns. Elevation, retrograde massage, and external compression can assist with edema reduction. If a skin graft was used, the donor site should also be monitored. The application of specific cross-fiber scar massage and silicon are appropriate once the wounds have healed. The PT should be consulted before massage is started on the skin graft margins. Active ROM emphasizing composite and isolated joint flexion and extension, abduction and adduction of the MP joints and opposition of the thumb should begin immediately postoperatively but care should be taken to avoid tension across the suture lines. Sensation should be monitored and protective techniques should be taught to those patients whose sensibility is compromised. Paresthesias often result from stretching the digital nerves and should resolve as healing progresses. The PTA should be aware of the early signs of CRPS. If this is suspected, it is important to inform the PT so the treatment program can be modified appropriately23,25(see later discussion). Passive ROM, gradual strengthening, and closed-chain weight bearing can begin as soon as wound healing permits.

Carpal tunnel syndrome

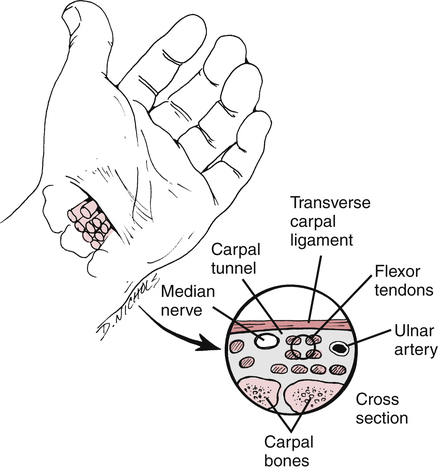

A compression neuropathy occurs when adjacent structures constrict a peripheral nerve, limiting its blood supply and resulting in impaired nerve conduction. Specific sites have been associated with compression of the radial, ulnar, and median nerves. If the adjacent tissue restricts gliding of the nerve, the nerve will be subjected to stretch that can also result in paresthesias and pain. This is referred to as a nerve entrapment. The most common compression neuropathy in the upper extremity is that of the median nerve at the wrist.32

Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) refers to the symptoms that occur when the median nerve is compressed or entrapped at the wrist. The carpal tunnel is formed by the carpal bones and the transverse carpal ligament and contains the median nerve and nine flexor tendons (Fig. 23-17). Increased friction and pressure within the tunnel constrict the nerve and produce sensory problems such as decreased sensation, pain, and tingling; and motor problems including loss of the thenar intrinsic muscles (flexor pollicis brevis [FPB], abductor pollicis brevis [ABPB] and opponens pollicis [OP), and loss of the first two lumbrical muscles.

There are many possible causes for CTS, including anatomic changes from arthritis, fractures, or cysts; systemic conditions such as diabetes, hypothyroidism, aging, pregnancy, or alcohol abuse; environmental factors such as solvent exposure or decreased temperatures; and occupational factors such as tasks requiring forceful, repeated motions in extreme postures (cumulative trauma), or vibration.32

The clinical symptoms of CTS include numbness of the thumb and radial digits, tingling, pain that is often worse at night, clumsiness in hand activity, weakness of grip and pinch, atrophy of the thenar muscles, and swelling in the hand and forearm.12,22

Conservative physical therapy management of carpal tunnel syndrome focuses on identifying and altering the factors that may produce symptoms. Extreme flexion or extension of the wrist compress the contents of the tunnel, so patient education should be directed to avoiding these positions. Anything that constricts the wrist such as tight sleeves, watchbands and bracelets or applies pressure over the median nerve when the pronated arm is resting against a desk can contribute to the problem. Custom splints that hold the wrist in 0° to 20° of extension should be worn day and night22 for several weeks to keep the carpal tunnel open. Deep (1 MHz) pulsed ultrasound, nerve gliding exercises, carpal bone mobilization, and yoga have all been shown to be successful in reducing the symptoms.22

Medical management may include nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), or the physician may elect to inject the area with a corticosteroid to reduce pain and swelling.12 Failure of nonoperative treatment or the presence of thenar atrophy are indications for surgical intervention. In surgery, the transverse carpal ligament is divided and any inflammatory tissue removed. The wrist is immobilized for 1 to 2 weeks, but digit ROM can begin immediately. The patient is taught to avoid simultaneous wrist and finger flexion in order to avoid bowstringing of the flexor tendons. Nerve gliding and differential tendon gliding (Fig. 23-18) is emphasized to avoid adhesions.

Complex Regional Pain Syndrome

One of the most difficult problems in hand rehabilitation is the treatment of CRPS. This term is used for clinical conditions in which the pain resulting from an injury is abnormally severe and/or prolonged compared with that of a normal postinjury response. This includes conditions such as reflex sympathetic dystrophy (RSD) and causalgia, but has replaced the use of these terms.14,39 CRPS is further subdivided into type 1: without a nerve injury, and type 2: with a nerve injury. Both of these categories are further subdivided based on the presence or absence of sympathetic nerve involvement.14

Signs and symptoms

The presentation of this syndrome is variable, but there are four primary characteristics:

Pain: This can range from localized pain to a delayed, abnormally painful reaction to light touch that extends beyond the actual location of the stimulus.14,39 These patients often cannot tolerate any spontaneous touch; even air blowing on the extremity can produce extreme pain.

Pain: This can range from localized pain to a delayed, abnormally painful reaction to light touch that extends beyond the actual location of the stimulus.14,39 These patients often cannot tolerate any spontaneous touch; even air blowing on the extremity can produce extreme pain.

Trophic changes: Atrophy results in differences in hair and nail growth, shiny, tight skin, loss of fat pads in the fingertips, and osteopenia.14,15,39

Trophic changes: Atrophy results in differences in hair and nail growth, shiny, tight skin, loss of fat pads in the fingertips, and osteopenia.14,15,39

Autonomic disturbances: This system controls microvascular perfusion and sweat gland activity. The patient may present with the affected fingers being warm or cool compared with the other side. There may be profuse sweating or extreme dryness of the skin. Edema usually is present. There may be dramatic color changes from pale and cyanotic, to mottled to red and warm, all within the same treatment session. Increased sympathetic nerve activity may also lead to increased pilomotor activity (goose bumps).14,15,39

Autonomic disturbances: This system controls microvascular perfusion and sweat gland activity. The patient may present with the affected fingers being warm or cool compared with the other side. There may be profuse sweating or extreme dryness of the skin. Edema usually is present. There may be dramatic color changes from pale and cyanotic, to mottled to red and warm, all within the same treatment session. Increased sympathetic nerve activity may also lead to increased pilomotor activity (goose bumps).14,15,39

Functional impairment: The patient is reluctant to use the hand and/ or entire extremity because of pain. Fine and gross coordination are disturbed. A typical, imbalanced hand posture is assumed with the MPs in extension and PIPs in either flexion or extension. The patient may have difficulty localizing tactile stimuli and may have an altered perception of his own hand, regarding it as foreign.7

Functional impairment: The patient is reluctant to use the hand and/ or entire extremity because of pain. Fine and gross coordination are disturbed. A typical, imbalanced hand posture is assumed with the MPs in extension and PIPs in either flexion or extension. The patient may have difficulty localizing tactile stimuli and may have an altered perception of his own hand, regarding it as foreign.7

Incidence

This condition is seen in both sexes, but is most prevalent in 30- to 55-year-old women. There is a higher incidence in smokers. The most common injury associated with CRPS is fracture of the distal radius and ulna.14 Patients often report a tight cast as their first sign of discomfort. Other surgeries complicated by postoperative CRPS include carpal tunnel release, De Quervain release, distal ulna surgery, and dermofasciectomy for Dupuytren release.14

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is made based on clinical criteria, and early recognition and treatment are the best predictors of pain relief and functional recovery.14 Bone scans, radiographs, cold stress tests, and microvascular perfusion tests contribute to the confirmation of the diagnosis.14,39 PT evaluations of pain threshold, fine and gross coordination, grip strength, and ROM provide additional information.14,15,39 The use of agents that interrupt the sympathetic nervous system differentiate types of CRPS and are used as part of the treatment when the sympathetic system is implicated.14,15,38

Treatment

A multidisciplinary approach including the surgeon, internist, pain specialist, PT, PTA, psychologist, and/or psychiatrist is recommended.14,15,39 Pharmacological management falls into two categories: analgesics to relieve pain, and drugs that affect the sympathetic nerves, such as antidepressants and corticosteroids.14,39 Surgery may be considered to correct the underlying source of pain, if it is identified. This can be a nerve entrapment, neuroma, or joint derangement.14

The entire limb should be treated with special attention to the shoulder because adhesive capsulitis is frequently present.38 Maintenance of motion is a primary goal. Splints are used between exercise sessions to help prevent contractures and reduce pain. Active ROM with special attention to the MP and PIP joints, isometrics, and gentle, pain-free passive ROM can be used. Light, bimanual activities can help integrate the involved extremity and restore movement patterns. Aerobic activities to increase cardiac output may help stabilize the vasomotor system and assist the patient to feel some physical accomplishment. Joint mobilization is not indicated and can be detrimental. Positive results have been reported for stress loading programs. These programs use active distraction and compression of the extremity during which the patient alternates weight-bearing scrubbing with weighted carrying. This provides proprioceptive input to the extremity without joint motion.33

MOBILIZATION OF THE WRIST AND HAND

As with other joints, many different techniques are used. This discussion introduces only a few of the more common and easily performed techniques. The intricate and complex nature of the wrist and hand demands mastery of anatomy, kinesiology, pathomechanics of injury, and biomechanics to effectively perform the more difficult techniques described in orthopedic texts.37

Mobilization of the Wrist

Anterior, posterior, medial, and lateral glides of the wrist are performed with the patient either sitting with the affected arm supported or supine. The PTA uses one hand to stabilize the distal radius and ulna on the dorsal aspect while firmly grasping the proximal row of carpal bones with the other hand.37 Using the hand supporting the carpal bones, the PTA directs an anterior and posterior force or a medial and lateral force to “glide” the carpal bones from the stabilized distal radius and ulna (Fig. 23-19).37

Distraction of the carpals is done with the patient either sitting or supine. The hand position is exactly the same as described in the preceding, but the direction of force is distal or longitudinal to the radius and ulna. This direction of force distracts or displaces the carpal bones from the stabilized radius and ulna (Fig. 23-20).37

Mobilization of the Hand

Anterior, posterior, medial, and lateral glides of the MP joint can be performed with the patient supine or sitting. The PTA uses one hand to stabilize the shaft of the affected metacarpal while firmly grasping the proximal phalanx with the other hand. With the metacarpal firmly stabilized, the PTA uses the hand contacting the phalanx to direct an anterior, posterior, or medial and lateral force that glides the MP joint (Fig. 23-21).37

Distraction of the MP joint occurs with the patient in the same position as described in the preceding. With the hand placement the same, the direction of force is applied to distract the phalanx from the stabilized metacarpal (Fig. 23-22).37

GLOSSARY

Bennett fracture Fracture of the palmar base of the proximal first metacarpal.

Mallet finger Interruption of the extensor tendon mechanism over the DIP joint.