20

Orthopedic Management of the Lumbar, Thoracic, and Cervical Spine

Cheryl Sparks, Joseph Kelly and Gary A. Shankman

1. Outline and describe basic mechanics of the lumbar spine.

2. Discuss and apply the principles of fundamental mechanics of lifting.

3. Identify common sprains and strains of the lumbar spine.

4. Discuss common methods of management and rehabilitation of lumbar spine sprains and strains.

5. Identify and describe injuries to the lumbar intervertebral disc.

6. Define and describe methods of quantifying back strength.

7. Define and describe components of the back school model.

8. Define ergonomic and functional capacity evaluations.

9. Define spinal stenosis and describe methods of management and rehabilitation.

10. Define and contrast the terms spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis.

11. Describe methods of management and rehabilitation for spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis.

12. Identify common lumbar and thoracic spine fractures.

13. Define kyphosis, lordosis, and scoliosis.

14. Identify and describe methods of management and rehabilitation for kyphosis and scoliosis.

15. Identify and describe common cervical spine injuries, and discuss methods of management and rehabilitation.

In an age when health care expenditures are a concern for many, back pain continues to cost billions of dollars in intervention and lost labor.42,45 It is imperative that the physical therapist assistant (PTA) possess a sound understanding of the anatomy and appropriate management of patients with various spinal disorders. In this chapter the PTA is introduced to overall symptomatology and effective intervention strategies for some of the more prevalent diagnoses affecting the spine.

THE LUMBAR SPINE

Perhaps no other medical condition draws as much attention from researchers and clinicians as the identification and management of lumbar spine injuries. The primary cause of disability in the middle-aged working class adult is related to low back pain and accounts for approximately $50 billion in health care costs annually in the United States.26,42,45 Lumbar spine injuries are also to blame for literally millions of lost work days per year in the United States and internationally. The rate of disability from injuries to the low back was estimated over a 10-year period to be a staggering 14 times greater than the rate of population growth for that same period.1,15 Overall, lumbar spine injuries are the second leading cause of all physician visits in the United States and the prevalence of low back pain in the population is close to that of the common cold.1,5,8,16,17,42

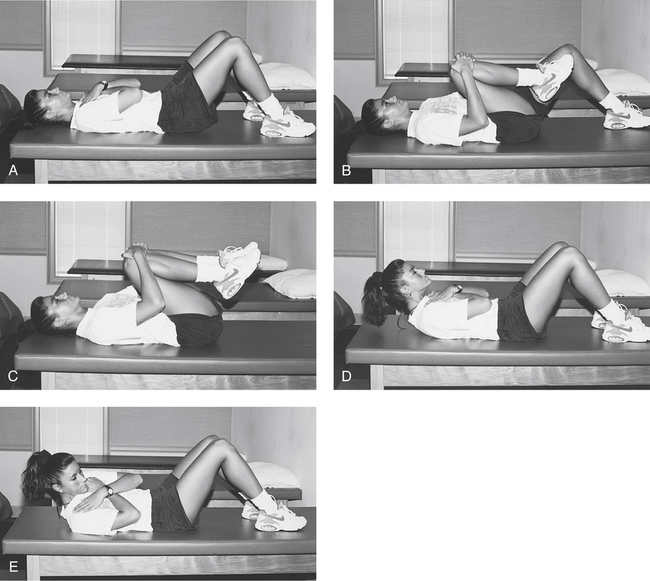

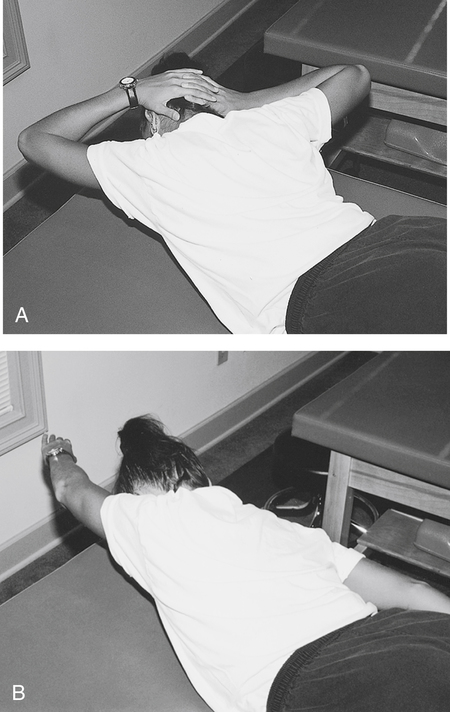

Historically, absolute bed rest, medications, thermal agents (e.g., hot packs or ultrasound), and a series of rudimentary lumbar flexion exercises (e.g., pelvic tilts, single knee-to-chest, double knee-to-chest, and partial direct and oblique sit-ups) (Fig. 20-1) were the components of a typical protocol for lumbar sprains, strains, and disc-related pathologic conditions. It is now widely accepted that active rest and resumption of function has a significant impact on improving long-term outcomes.20,24

Basic Mechanics

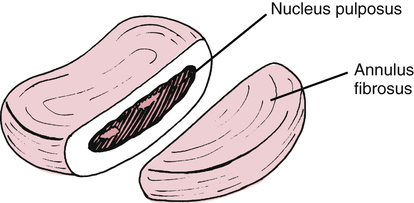

In the adult spine there are 23 intervertebral discs found in between the vertebral bodies (Fig. 20-2). The outer wall of the disc is called the annulus and comprises 12 to 18 concentrically arranged rings of fibroelastic cartilage.30,56 Contained within the annulus is the nucleus pulposus. Nuclear material is a mucopolysaccharide gel30 that transmits forces, equalizes stress, and promotes movement.55 The annulus provides stability, enhanced movement between vertebral bodies, and minimal shock absorption. The greater portion of shock absorption comes from the vertebral body.56,65

The intervertebral disc is largely avascular and aneural. The vascular supply to the disc is provided by diffusion from the vertebral bodies above and below the disc.14,30,49,56 The outer one third of the annulus is said to be innervated along with the facet joint capsule and exiting nerve roots.14 When injured, without an intense vascular response, the disc has a limited capacity to heal and repair. In addition, degenerative changes also occur within the disc as a normal process of aging throughout the life span.

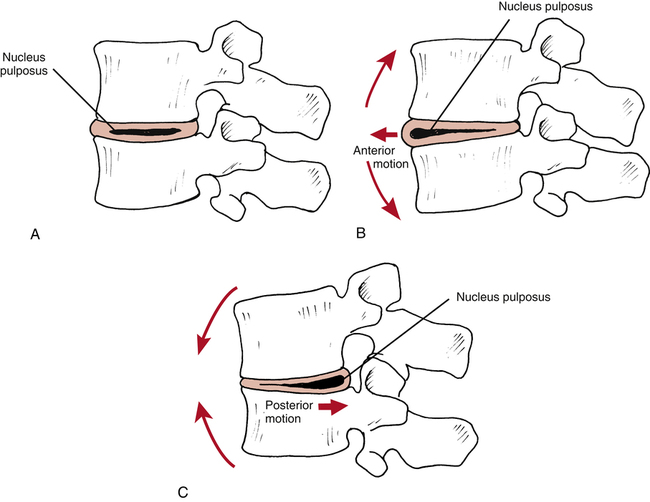

A popular theoretical model describes the fluid mechanics of the disc (nucleus pulposus) influenced by the motion of the lumbar vertebral segments. McKenzie49 describes flexion and extension motion of the spine as having clinically significant effects on the nucleus’s direction of movement (Fig. 20-3, A). The theoretical model proposes when positional changes occur in the lumbar spine, from flexion to extension, the nucleus moves anteriorly (Fig. 20-3, B).49 Conversely, when the spine moves from extension to full flexion, the nucleus tends to displace or move posteriorly (Fig. 20-3, C). Thus it is necessary to fully understand the individual nature of each injury and avoid or enhance certain motions and postures as directed by the physical therapist (PT).

The lumbar spine is composed of five anterior convex and posterior concave segments that produce the recognizable lordotic curve. Normal lordosis is increased with spinal extension and reduced with spinal flexion. The lumbar spine serves to support the weight of the upper body and dissipate compressive loads with minimal production of muscular torque. As a result significant forces are transmitted through the intervertebral disc during certain motions. Allman1 describes lumbar motion and postural alterations as producing significant pressure within the disc (intradiscal pressure). The compressive forces that influence intradiscal pressure are as follows1:

Standing: Disc pressure is equal to 100% of body weight

Standing: Disc pressure is equal to 100% of body weight

Supine: Disc pressure is less than 25% of body weight

Supine: Disc pressure is less than 25% of body weight

Side-lying: Disc pressure is less than 75% of body weight

Side-lying: Disc pressure is less than 75% of body weight

Standing and bending forward: Disc pressure is approximately 150% of body weight

Standing and bending forward: Disc pressure is approximately 150% of body weight

Supine with both knees flexed: Disc pressure is less than 35% of body weight

Supine with both knees flexed: Disc pressure is less than 35% of body weight

Seated in a flexed position: Disc pressure is approximately 85% of body weight

Seated in a flexed position: Disc pressure is approximately 85% of body weight

Bending forward in a flexed posture and lifting: Disc pressure is close to 275% of body weight

Bending forward in a flexed posture and lifting: Disc pressure is close to 275% of body weight

Intradiscal pressure also can be expressed in terms of pressure or load measured within the intervertebral lumbar disc. Cailliet9 reports that isometric abdominal sets produce approximately 110 kg of pressure within the disc, whereas walking produces 85 kg; sitting, 100 kg; bilateral straight-leg raises in supine position, 120 kg; and lifting with a flexed torso and knees held straight, an astounding 340 kg of intradiscal pressure. This information may help clarify the rationale for protective postures, lifting protocols, and appropriate body mechanics, as well as prescribed exercises for specific lumbar spine conditions.

Muscle Strains

Although some authorities27 point out that most low–back–related dysfunction results from soft-tissue injury, it is important to note that many other structures can potentially be involved (ligaments, disc, nerve tissue, and bone) and often the exact pathoanatomic cause of pain is elusive. The function however of the lumbar spine musculature is to contribute to dynamic stability.55 Panjabi and co-workers55 have identified the need for specific low back strengthening to reduce injury and “to stabilize the spine within its normal physiologic motions.”

Muscle strains of the lumbar spine are common and general treatment goals are as follows62: reduce or eliminate inflammation (pain and swelling), restore muscle strength and control, restore flexibility, enhance cardiorespiratory fitness, restore function, and protect the affected area from further injury through education and supervised practice of proper lifting mechanics.

Ligament Sprains

These spinal ligaments69 can be injured by a sudden violent force or from repeated stress. The PT conducts a comprehensive examination of the patient to confirm or deny the presence of segmental instability (hypermobility resulting from ligament sprain) and evaluate the degree of pain with or without active or passive movement of the lumbar spine in general or in individual segments.1,5 In addition to isolated ligament sprains, muscle strains can be superimposed, making the identification of specific single-ligament sprains exceedingly difficult. The management of lumbar ligament sprains essentially parallels the care of muscle strains. Each patient has specific, identified impairments and goals that must be addressed individually through the initial evaluation performed by the PT. The PTA, under the direction of the PT, must identify which specific positions are contraindicated by carefully reviewing the initial evaluation data. Both the short- and the long-range goals for recovery from lumbar strains and sprains emphasize protecting the spine from unwanted forces and positions.

Radiculopathy

Radiating pain into one or both lower extremities could signify nerve root compression from an adjacent herniated intervertebral disc. A sensitive test for nerve root compression or disc herniation requires the patient to be supine while the symptomatic leg is raised passively with the knee completely extended. This is called a straight leg raise test. When the uninvolved, or asymptomatic, lower extremity is tested in the same manner, this is called a crossed straight leg raise test. The crossed straight leg raise has been found to be highly specific for disc herniation. These tests are considered positive only if radicular pain is increased or reproduced.21 Any positive findings noted during the initial examination performed by the PT should be confirmed or denied.62

Lumbar Intervertebral Disc Pathologies

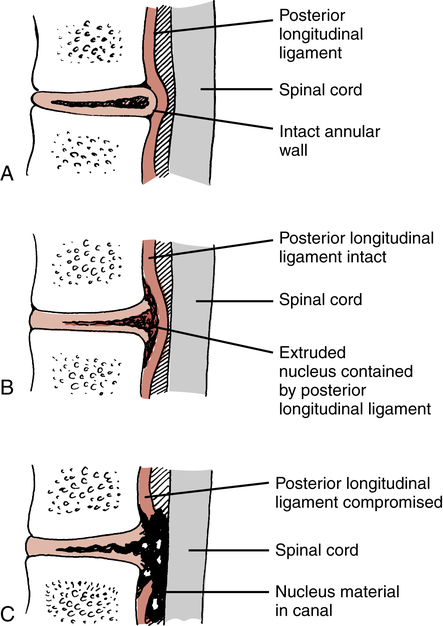

Various terms are used to describe injuries to the disc. Although “slipped disc” is a common expression used to describe various ailments of the low back among the general population, a disc does not “slip” from within its confines between the vertebral bodies. Also incorrectly applied are the two terms, disc bulge and herniated nucleus pulposus (HNP). These are frequently used interchangeably. To clarify, a HNP can be defined by specific nomenclature to more precisely describe the injury. Miller51 describes the three categories of HNP as protruded, extruded, and sequestrated. In a disc protrusion, the nucleus bulges against an intact annulus (Fig. 20-4, A). This would more closely resemble the layperson’s disc bulge terminology. An extruded disc is characterized by the nucleus extending through the annulus, but the nuclear material remains confined by the posterior longitudinal ligament (Fig. 20-4, B). Finally, in a sequestrated disc, the nucleus is free within the canal (Fig. 20-4, C).

Macnab46 offers a variation of this classification model:

Regardless of the exact nature of the injury, a HNP remains primarily a disease of young to middle-aged adults.51 Common age-related degenerative changes that occur within the disc include decreased hydration, with a decreased water content from 70% to 88% by the third decade; biochemical changes in the glycosaminoglycans of the nucleus; and increases in collagen. As a result these changes make disc herniations rare in elderly people.51,56

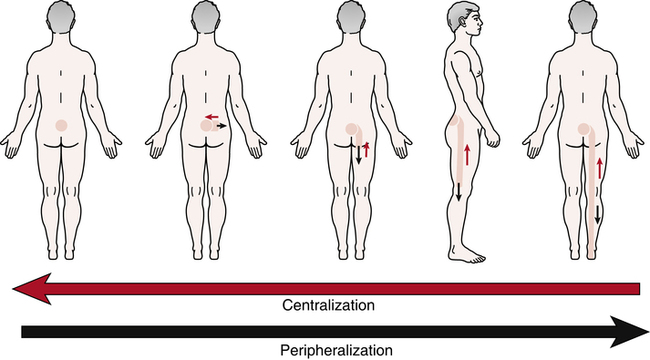

When examining a patient who exhibits radicular signs, the PT confirms or denies the presence of peripheralization or centralization phenomena by observing a directional preference.41,49 These conditions identified during the initial examination are defined by Kisner and Colby41 as follows: “When repeating the forward-bending test, the symptoms increase or peripheralize. Peripheralization means the symptoms are experienced further down the leg.” Centralization is defined by McKenzie49 as, “the phenomenon whereby, as a result of the performance of certain repeated movements or the adoption of certain positions, radiating pain originating from the spine and referred distally, is made to move away from the periphery and toward the mid-line of the spine” (Fig. 20-5). The evaluation data obtained by the PT regarding the presence of a directional preference is essential in determining treatment.

Spondylolysis and Spondylolisthesis

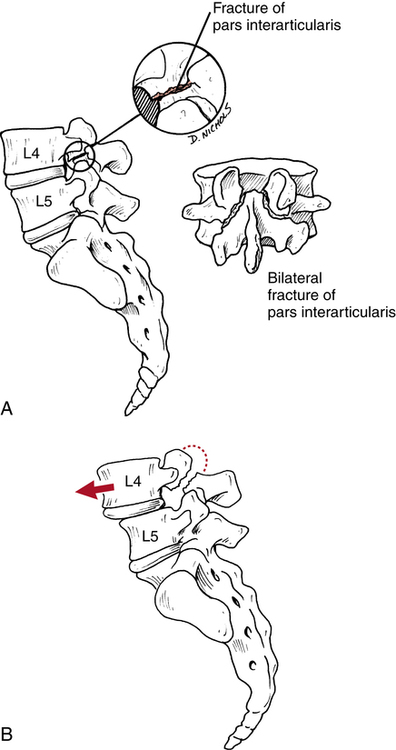

Spondylolysis is a bony defect (stress fracture or fracture) in the pars interarticularis of the posterior elements of the spine (Fig. 20-6, A).8,9,15,21,51,56,62 Spondylolisthesis, on the other hand, describes a forward slippage of one superior vertebra over an inferior vertebra (usually L4-L5 and L5-S1)18,21 as a result of instability caused by the bilateral defect in the pars interarticularis (Fig. 20-6, B).8,9,15,21,51,56,62 There are specific classification types, as well as degrees of slippage or “migration” of the vertebrae in the disease process of spondylolisthesis.21 Five types, or classifications, have been identified, as follows8,21,51:

Type I: Congenital or dysplastic. Results from a “congenital malformation of the sacrum or neural arch of L5, which allows forward slippage of L5 on the sacrum.”8 Most common in children.

Type I: Congenital or dysplastic. Results from a “congenital malformation of the sacrum or neural arch of L5, which allows forward slippage of L5 on the sacrum.”8 Most common in children.

Type II: Isthmic spondylolisthesis. The most common type, affecting persons 5 to 50 years of age.51 Usually a result of mechanical stress that causes a stress fracture at the pars interarticularis.21,51

Type II: Isthmic spondylolisthesis. The most common type, affecting persons 5 to 50 years of age.51 Usually a result of mechanical stress that causes a stress fracture at the pars interarticularis.21,51

Type III: Degenerative spondylolisthesis. Most commonly affects the older population. Characterized by a loss of ligament integrity (or stability) that results in forward slippage of the vertebrae. Generally associated with the normal aging process.8

Type III: Degenerative spondylolisthesis. Most commonly affects the older population. Characterized by a loss of ligament integrity (or stability) that results in forward slippage of the vertebrae. Generally associated with the normal aging process.8

Type IV: Traumatic spondylolisthesis. Caused by trauma that produces an acute fracture of the pars interarticularis. Casting is the most appropriate form of treatment.8 Because of their generally high levels of physical activity, this type usually affects young patients.51

Type IV: Traumatic spondylolisthesis. Caused by trauma that produces an acute fracture of the pars interarticularis. Casting is the most appropriate form of treatment.8 Because of their generally high levels of physical activity, this type usually affects young patients.51

Type V: Pathologic spondylolisthesis. Characterized by bone tumors that affect the pars interarticularis.

Type V: Pathologic spondylolisthesis. Characterized by bone tumors that affect the pars interarticularis.

The degree or grade of slippage is determined radiographically by the examining physician and is defined as the amount of forward displacement of the superior vertebrae over the inferior vertebrae, as outlined in the following:8,15,51

The cause of the defect in the pars interarticularis is in part a congenital weakness in this area. In addition, the pars interarticularis is subjected to high levels of mechanical stress.64,65 Authorities also suggest that the primary initial cause of the most common type of spondylolisthesis (isthmic) is fatigue fracture of the pars interarticularis.65

Patients primarily report pain with extremes of lumbar motion, especially extension. The pain generally follows the belt line.37 During examination, the PT also may identify a palpable step-off between the affected lumbar vertebrae (usually L4-L5) because of the forward slippage.15

The patient may require more specific attention when there is a greater degree of slippage with significant symptoms. Generally, pain and muscle spasm are addressed with physician-prescribed analgesics, muscle relaxants, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and agents (heat, ice, ultrasound, and electrical stimulation) to alleviate acute pain and swelling. If the pain is related to a fatigue fracture of the pars interarticularis, initial treatment focuses on managing stress to the fracture site using a lumbosacral corset or orthosis, which reduces anterior shearing forces through the fracture site and allows for bone healing.21,37

The cornerstone in the care of spondylolisthesis is application of abdominal and paravertebral muscle strengthening exercises to provide dynamic support for the spine during activity and avoidance of extreme lumbar extension. A young active patient must modify activities that directly influence the course of this disease. For example, weight lifting without proper precaution can contribute significantly to the occurrence of spondylolysis.19

Surgery is rare and usually is reserved for patients with radicular symptoms and high-grade slippage (grades III or IV), which compresses the nerve roots and causes neurologic signs.8,51 The type of surgery advocated in these cases is a decompression laminectomy (to reduce compression of the nerve roots) with fusion to stabilize the vertebral segments.8,51

Rehabilitation after surgery for spondylolisthesis is deferred until solid bony union is determined radiographically. The patient is usually in a lumbosacral orthosis that does not permit lumbar extension. During immobilization, the patient can ambulate as tolerated and perform rudimentary ROM and strengthening exercises for the upper and lower extremities (ankle pumps, quadriceps sets, and knee ROM). Once bone healing is confirmed, a gradually progressive program of abdominal strengthening (from isometrics to concentric and eccentric abdominal contractions), lumbar ROM (avoiding dynamic, ballistic, and extreme lumbar extension), general conditioning, and a progressive return to function is advocated.8,51

Spinal Stenosis

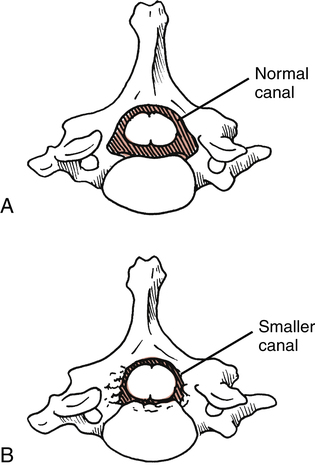

Lumbar spinal stenosis is defined as a narrowing of the spinal canal, which constricts and compresses nerve roots (Fig. 20-7).51 This gives rise to symptoms of neurogenic or spinal claudication, as follows:

1. Radicular ache into the thigh and less frequently into the calf8

This condition occurs in males “twice as often as females”51 and typically is observed during late middle age and older.29,51

Lumbar spinal stenosis is most commonly acquired as a result of degenerative arthritic changes that encroach on the diameter of the canal, producing nerve root compression.51 The patient with stenosis frequently complains of pain and increased symptoms with lumbar extension. Extension of the lumbar spine in a patient with stenosis further compresses the spinal canal, thereby increasing pain and paresthesias.15,29,51

During ambulation and gait training, an elderly patient typically demonstrates a forward-flexed trunk posture when using a walker. Under careful observation and questioning, the patient may suggest that leaning forward feels better and reduces back and leg pain. The role of the PTA is to continually educate the patient, reinforcing appropriate postures, body mechanics, and lifting techniques. Sitting and sleeping changes, as well as a general physical conditioning and weight management programs are also addressed and have been identified as an important adjunct in the overall management of patients with spinal stenosis.51 Whitman and colleagues63 demonstrated that subjects with spinal stenosis experienced greater improvements in pain and recovery at 6 weeks with manual therapy, exercise, and walking than subjects who just performed routine flexion exercises and walking. The physical therapy team should work together to provide the appropriate manual intervention followed by specific exercise and a walking program for the best management of patients with spinal stenosis.

Lumbar Spine Fractures

Fractures of the lumbar vertebrae generally occur after a profound traumatic event and can be classified according to the forces that produce the fracture. For example, compression, flexion, extension, flexion-distraction, flexion-rotation, and lateral flexion are forces that produce fractures.51 Lumbar spine fractures also can be described in terms that graphically depict a specific fracture deformity, including crush, wedge, burst, shear, slice, and teardrop fractures.51

Perhaps the most clinically relevant spine fracture for the PTA to consider is the vertebral compression fracture. Vertebral compression fractures are the most common osteoporosis-related spinal fracture with approximately 700,000 occurring per year, and the prevalence of vertebral compression fractures increases with age.15,29,43

Many benign activities can produce compression fractures in an elderly population of patients with osteoporosis.8,43 Care must be taken to ensure that no rapid deceleration occurs when an elderly patient transfers to a bedside commode or any other hard surface. This seemingly trivial activity frequently causes multilevel compression fractures in patients with osteoporosis. Compression fractures produce symptoms ranging from acute local pain to essentially no signs at all.43 Thus subtle complaints of pain caused by typical daily activities, such as bending, lifting, or rising from a chair, must be viewed with a high level of suspicion in elderly patients.43

Treatment of compression fractures focuses on relief of pain; authorities29,43 advocate activity modification, physician-prescribed analgesics, NSAIDs, heat, ice, massage, and electrical stimulation to control pain, swelling, and associated muscle spasm. During the acute and subacute phases of recovery, the patient with compression fractures must avoid thoracic or lumbar flexion activities.29 Repeated trunk flexion is contraindicated because it creates an anterior wedging of the vertebral bodies, producing greater stress and compression at the fracture site.29Appropriate exercise progression should target the muscles supporting or attached to the affected bone, and they will be determined by the PT. Exercises should be combined with postural correction, scapular stabilization, and improving weight-bearing patterns, strength, balance, and flexibility.

Treatment-Based Classification

Rehabilitation of the lumbar spine is focused toward impairments rather than labeling pathoanatomic findings. As a result, when a patient experiences low back pain, the evaluating PT assimilates information from the patient history, examination, and current best evidence, and classifies the patient into the most appropriate category. The rehabilitation plan will include a multimodal approach that categorizes patients based on their overall symptomatology and response to a specific intervention. This system has been identified as treatment-based classification (TBC).6

The TBC system consists of subgroupings through which the patient moves fluidly in and out of during the course of care. The interventions within these categories include manual therapy and exercise,12,22 specific exercise for directional preference,7,63 traction,24,25 neuromuscular reeducation and stabilization exercise,34,52,54 aerobic exercise, and recommendations to stay active. PTs will use their findings from the clinical examination to match the patient with the most appropriate intervention. Research has shown patients managed with this systematic approach experience significant decreases in pain and disability.6,24 For the PTA it is important to be aware of the categories along with exercise and educational concerns within each.

Some patients with acute or chronic low back pain will benefit from first restoring mobility in the spine, and therefore these patients will initially be placed in the manual therapy and exercise category. The PT will address any segments that need to be mobilized before initiating an exercise program for the patient. Early exercises are chosen to enhance the restoration of normal movement in the lumbar spine and include pelvic rocking and abdominal bracing. Patients with short duration of symptoms (less than 2 or 3 weeks), no symptoms distal to the knee, and low fear-avoidance behaviors are expected to experience a 50% reduction in disability in 1 to 2 weeks on the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI)Questionnaire.12,22 However the PT may choose to progress the patient gradually based on the presence of elevated fear avoidance beliefs noted on the Fear Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ).28

Patients with more chronic or recurring symptoms of low back pain are managed with neuromuscular reeducation and stabilization exercise. These patients often present with an average straight leg raise greater than 91° and the presence of aberrant motions. Exercises focus on recruitment and control of the multifidi, transversus abdominis, internal and external obliques, and the gluteal musculature. With this strategy, patients can also expected to achieve a 50% reduction in disability on the ODI in 8 weeks.34

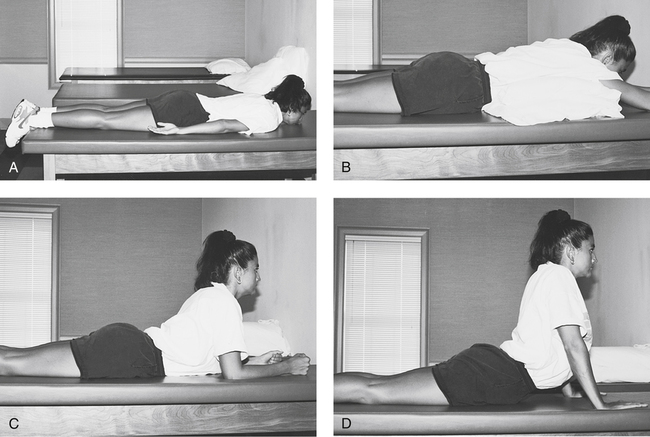

In the presence of a directional preference, the patient experiences a centralization phenomenon where distal lower extremity symptoms and low back pain are lessened with repeated movements into a particular direction. The symptoms become more centrally located with certain motions. An example of a repeated movement or prone progression is shown in Figure 20-8. Research has shown the adoption of the appropriate exercise program based on the patient’s directional preference will allow for less pain and disability for up to 6 months.7 Occasionally patients with distal lower extremity symptoms and neurologic signs will not demonstrate centralization with movement testing. In which case, the patient may benefit from mechanical traction in addition to specific exercises.24

Invasive Management

When conservative physical therapy (including active rest, medications, exercise, and postural correction) fails to bring significant relief from symptoms, the physician may offer several invasive procedures. For some patients whose persistent radicular pain (sciatica) cannot be controlled by conservative measures, the physician may prescribe an epidural steroid injection to relieve symptoms.21,51 These injections are given only to relieve pain and reduce inflammation, and are not intended as a curative procedure to correct any neurologic deficits.

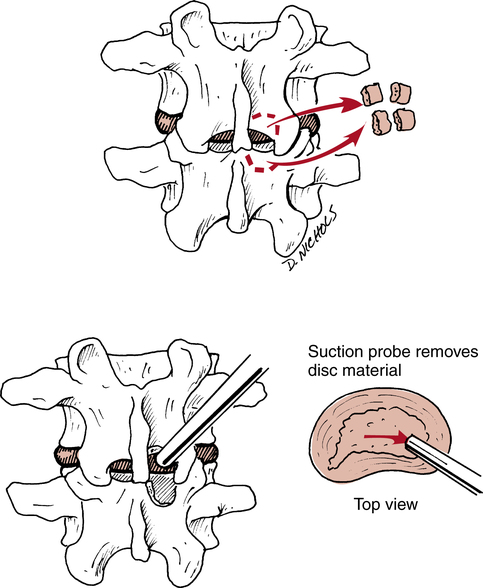

Patients may undergo surgery in the presence of a large disc herniation. As described by Miller51 and Eismont and Kitchel,21 the most common procedure is a laminotomy with a decompression discectomy. In this procedure the physician gains exposure to the herniated disc by cutting into the lamina and then removing all nonviable disc material, thereby decompressing the affected nerve root (Fig. 20-9). While some patients report good or excellent results with this particular surgical procedure, as many as 30% of these patients may have significant back pain at long-term follow-up.18,51 Other invasive procedures exist, such as microsurgical discectomy and automated percutaneous discectomy.

For the first 3 days after surgery the patient is limited to sitting for no more than 1 hour at a time and must maintain proper spinal position with no flexion.10 The PTA continually reinforces and encourages proper posture during the first week of recovery. The patient should be cautioned to avoid forward bending and trunk rotation.

The patient must achieve increased motion, controlled pain, improved endurance, and sufficient strength before beginning a general conditioning program after surgery. The longer recovery period is needed to allow for proper soft-tissue healing, bone healing, and control of inflammation and pain before subjecting the affected area to stress. From 3 to 5 weeks after surgery, the goals of recovery are identified as restored lumbar motion, normalized upper and lower extremity strength, improved aerobic fitness, and decreased pain and swelling.10

Fundamental Mechanics of Lifting

Forces and stresses related to lifting, sitting, standing, walking, sleeping, and twisting are common to all activities of daily living (ADLs). O’Sullivan and colleagues53 have identified a novel concept to instruct patients in proper lifting mechanics, listing the “five Ls” of lifting: load, lever, lordosis, legs, and lungs.

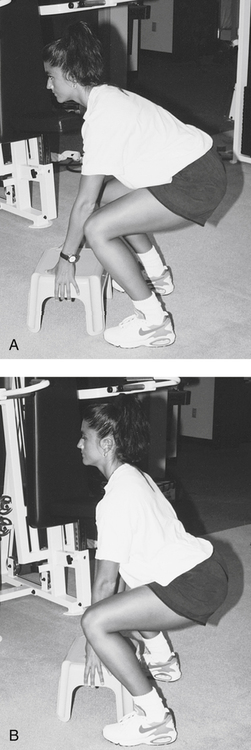

Kaiser and co-workers40a have identified a lumbar stabilization model comparing two lumbar spine postures during lifting. In the first posture (tested electromyographically) the starting position is characterized by a posterior pelvic tilt. The abdominal muscles are in a shortened position, the lumbar paravertebral muscles show no electromyographic activity, the posterior ligaments and posterior annular wall are stretched, the knees are in a position of decreased leverage, and the patient’s center of gravity is posterior to the base of support (Fig. 20-10, A).14 In the second posture, the patient’s lumbar lordosis is maintained during the lift. The abdominal muscles are in their normal anatomic length, the paravertebral muscles contracted, the posterior ligaments relaxed, the knees in an optimal leverage position, and the patient’s center of gravity over the base of support (Fig. 20-10, B).

Prevention and Education for Back Dysfunction: The Back School Model

Many back schools involve a 1- or 2-hour class (consisting of lectures, slides, demonstration, and participation) each week for 4 to 6 weeks. Each session or class builds on the previous lecture to convey the principles seen in spinal anatomy, causes of back dysfunction, risk factors, posture, body mechanics, and treatment approaches.1 Back schools can be based in outpatient physical therapy clinics, hospitals, industrial health clinics, wellness programs at work, or community fitness centers. In every case, the program should be under the direction and supervision of a PT, physician, or both.

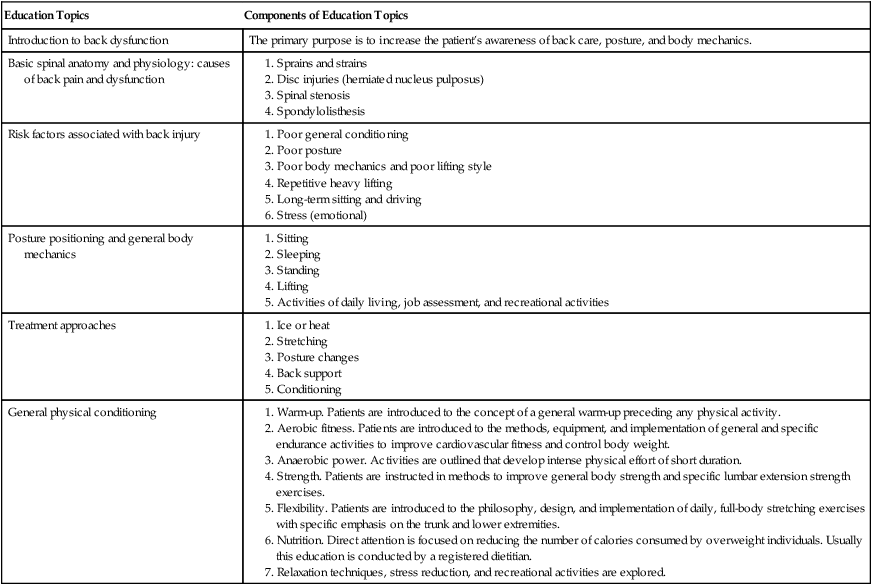

Allman1 has identified the outline in Table 20-1 as an appropriate general back school program. The curriculum clarifies the rudimentary concepts of education and prevention for a wide variety of back-related problems. The PTA who presents this information must be given specific information, evaluation data, indications, and contraindications for each patient participating in the back school program. In this way all phases of recovery and prevention can be individualized for each patient.

Table 20-1

Appropriate General Back School Program

| Education Topics | Components of Education Topics |

| Introduction to back dysfunction | The primary purpose is to increase the patient’s awareness of back care, posture, and body mechanics. |

| Basic spinal anatomy and physiology: causes of back pain and dysfunction |

1. Warm-up. Patients are introduced to the concept of a general warm-up preceding any physical activity.

2. Aerobic fitness. Patients are introduced to the methods, equipment, and implementation of general and specific endurance activities to improve cardiovascular fitness and control body weight.

3. Anaerobic power. Activities are outlined that develop intense physical effort of short duration.

4. Strength. Patients are instructed in methods to improve general body strength and specific lumbar extension strength exercises.

5. Flexibility. Patients are introduced to the philosophy, design, and implementation of daily, full-body stretching exercises with specific emphasis on the trunk and lower extremities.

6. Nutrition. Direct attention is focused on reducing the number of calories consumed by overweight individuals. Usually this education is conducted by a registered dietitian.

7. Relaxation techniques, stress reduction, and recreational activities are explored.

From Allman FL: Back school program. In Introduction to back injuries, Atlanta, 1990, The Atlanta Sports Medicine Clinic.

Most recently in a systematic review of completed research, Martimo and colleagues48 concluded that the evidence to support back school programs is lacking. The effectiveness of a back school program in preventing pain, injury, and dysfunction is still under scrutiny. Despite this lack in evidence, there is still value in patient education by the PT and PTA. Future studies may provide evidence that back school programs prevent further injury.

Ergonomics and Functional Capacity Evaluations

In concert with back injury prevention through education and in accordance with the back school model is the concept of ergonomics and the implementation of functional capacity evaluations (FCEs), which are also referred to as physical capacity assessments (PCAs), related to physical stress job analysis. The term ergonomics refers to a quantifiable system of job or ADL modification (or redesign) that allows for continued productivity while reducing work-related physical stress. As with the back school model, an FCE may require the PTA to prepare the evaluation area, set up all necessary testing equipment, and assist the PT with the collection, documentation, and storage of data. The implementation of an FCE is highly specific to the individual’s job task. Its goal is to identify risk factors associated with a particular job or activity and then quantify the physical capacity of the individual being asked to perform the specific task to reduce the risk of back injury. In most cases an FCE is administered to a patient recovering from a back injury before returning to the job. An FCE also can be used as a screening tool to acquire data related to preemployment risk assessment and management of back injuries. Certain job or activity risk factors have been identified33 that directly relate to the FCE. A few ergonomic risk factors are outlined by Hebert as follows33:

How low you bend to lift the load

How low you bend to lift the load

How far you twist with the load

How far you twist with the load

How far you reach with the load

How far you reach with the load

What the specific design of your seat is

What the specific design of your seat is

If there is sustained or repeated bending, twisting, or reaching

If there is sustained or repeated bending, twisting, or reaching

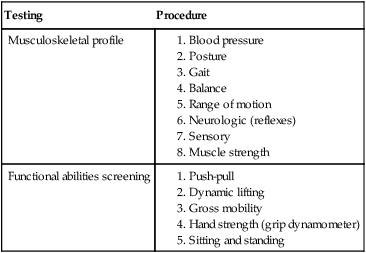

Authorities60 advocate a multiphase testing procedure that identifies the various components of an FCE, as shown in Table 20-2. Within each FCE the aerobic end point (heart rate exceeds 85% of maximum heart rate) and biomechanical analysis of the patient’s lifting-risk posture is assessed. In each section of the test, the parameters evaluated are performed directly as they relate to the specific job or task in question.

Table 20-2

Testing Procedure that Identifies the Various Components of a Functional Capacity Evaluation

| Testing | Procedure |

| Musculoskeletal profile |

From Work Site Partners, functional capacity evaluation system, industrial rehabilitation solutions. U.S. physical therapy system manual, Houston, 1994, USPT System Manual.

THE THORACIC SPINE

Thoracic Spine Muscle Injuries

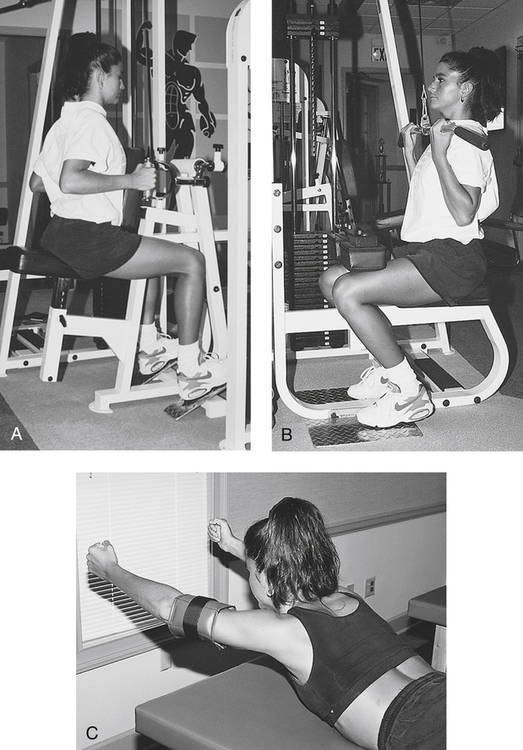

Prone thoracic and lumbar extension exercises are employed per patient tolerance. These involve a three-position progression from hands at the sides, to hands behind the head, and finally to arms fully extended while performing prone thoracic and lumbar extension. As pain is reduced and strength increases, the patient can begin isotonic strengthening exercises that focus on the scapular and thoracic spine muscles (Fig. 20-11).

Thoracic Disc Injuries

Thoracic disc herniations are rare (less than 0.3% of the population) and affect both men and women equally from the fourth through the sixth decades of life.8 The most common segments affected are between the ninth and twelfth thoracic vertebrae.8

The type of treatment employed for thoracic disc herniations depends on whether the disc is herniated laterally or centrally.8,21 A large central disc prolapse may produce symptoms of “spastic paraparesis, increased deep tendon reflexes, and a positive Babinski response.”21 However, lateral thoracic disc protrusions can produce signs more consistent with nerve root compression.

The PTA is exposed to both conservative care and postsurgical recovery after thoracic spine disc herniations. Less severe lateral disc herniations can be treated effectively with periods of active rest, analgesics, modalities to control pain and swelling, and epidural injections. More severe central disc herniations, involving progressive neurologic deficits, must be treated surgically to decompress the neurologic impingement.8,21 Recovery after thoracic decompression closely follows the time necessary for healing of bone and soft tissue with extensive periods of supportive bracing to protect the affected spine from unwanted forces, and a progressive regimen of active motion, strengthening, and endurance activities, and a return to function with specific limitations delineated within the protocol developed by the surgeon and PT.

Kyphosis

Kyphosis is defined as an increase in the thoracic posterior convexity that is manifested by a rounded-back (and protracted scapulae) posture. Kyphosis can be subdivided into congenital, neuromuscular, and postural categories.21 Osteoporosis, which can lead to multilevel thoracic compression fractures, causes anterior wedging of the involved segments and creates the kyphotic curvature.

The causes of pain associated with an increased thoracic convexity have been identified as stress originating from the posterior longitudinal ligaments, muscle fatigue resulting from stretched and weakened erector spinae and rhomboid muscle groups, and various postural and neurologic syndromes.41

The treatment of kyphosis depends on the degree of curvature, which is determined radiographically by the treating physician, any associated disc involvement, and the severity of symptoms.5 In advanced cases of postural kyphosis with profound curvature and significant symptoms, the patient may require supportive bracing of the thorax to minimize the compression associated with anterior wedging of the vertebral bodies. With less severe kyphosis, the PTA plays a critical role in patient education, postural awareness, and the application of specific exercises to simultaneously stretch the anterior shoulder and pectorals and strengthen the thoracic extension muscles.

As described, the patient does the three-progression prone thoracic extension exercises. In addition, the patient performs scapular adduction while lying prone with both arms held straight at 90°. Both arms are elevated while adducting the scapulae and holding the contracted position isometrically for 10 seconds.41 This position can be modified slightly by having the patient hold weights while performing scapular adduction with both elbows flexed, creating more of a prone rowing motion.

Scoliosis

Scoliosis can be identified as any lateral curvature of the cervical, thoracic, or lumbar spine.41 Scoliosis usually is idiopathic (cause unknown), but it also can result from neuromuscular causes or can be related to degenerative disease, osteoporosis, trauma, and postsurgical factors.51 Kisner and Colby41 identify the incidence of idiopathic scoliosis as being as high as 75% to 85% of all recognized types of scoliosis. Generally scoliosis can be recognized as either structural or nonstructural.41

Structural scoliosis is defined as an “irreversible lateral curve of the spine with fixed rotation of the vertebrae.”41 During the PT’s initial evaluation of structural scoliosis, the clinician will observe whether the identified lateral curve decreases with forward trunk flexion. If not, structural idiopathic scoliosis is not corrected by changes in the patient’s position or during active voluntary activities.41 Nonstructural scoliosis is classified as reversible, wherein the lateral curve dissipates with positional changes. In either case, pain is the foremost presenting feature of scoliosis,51 although cosmesis is a great concern. Other complaints involve decreased cardiopulmonary function (usually with thoracic curves greater than 65°) and neurologic symptoms associated with spinal stenosis.51

The nonoperative management of idiopathic scoliosis primarily involves the assistant in instructing the patient about therapeutic exercises outlined and prescribed by the PT. Scoliosis treatment involves both stretching and strengthening, much like kyphosis. Exercise by itself does not halt the progression or correct scoliosis.41 The effective use of therapeutic exercise is intended primarily to improve spinal motion, increase muscle strength, and reduce back pain.41

In addition to exercises, bracing also has been advocated in the treatment of scoliosis.41,51 However, bracing is intended to halt progression of the curve and not correct cosmetic deformity.51 Perhaps the most commonly used brace for scoliosis is the Milwaukee brace.41,51 Generally this brace is worn 23 or 24 hours a day.41 However, Miller51 suggests that part-time brace wearing is as effective as the traditional long-term application.

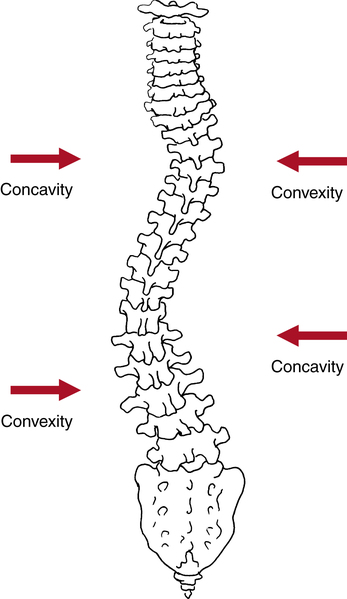

Stretching exercises directed toward the concavity must address all of the spinal muscles. Note that a right thoracic convexity results in a left lower thoracic concavity and associated right lumbar concavity with left lumbar convexity (Fig. 20-12). Strengthening exercises are performed for all of the muscles affected on the convex side of each lateral curve.

Various stretching exercises can be performed in prone, side-lying, or heel-sitting position.41 While prone, the patient places both hands behind his or her head while tilting the thorax away from the concave side of the curve (Fig. 20-13, A). In another prone stretching exercise, the patient reaches overhead and extends the arm on the concave side, thereby effectively stretching the thoracic concavity (Fig. 20-13, B).

In the heel-sitting position, the patient places both hands forward and flat while emphasizing long-axis stretching. The lateral stretching component of this exercise is accomplished by having the patient slowly stretch both arms laterally away from the concave side of the curve (Fig. 20-14).

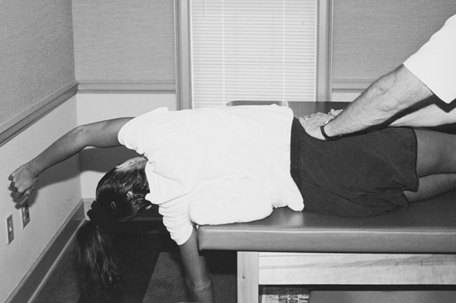

Static stretching also can be performed with the patient lying on his or her side. Place a small, soft rolled pillow or towel directly under the apex of the thoracic convex curve and support and stabilize the pelvis. For an advanced progression of side-lying stretching, the patient lies over the apex bolster toward the end of a treatment table (Fig. 20-15).

Specific lateral strengthening can proceed with the patient in a side-lying position on the concave side of the curve. The PTA should stabilize the trunk, then have the patient lift the trunk up toward the convex side of the curve (Fig. 20-16). This exercise can be viewed as a side-lying sit-up.

While this brief discussion has focused on a few rudimentary stretching and strengthening exercises for mild to moderate idiopathic scoliosis, an outline of surgical procedures to correct severe scoliosis is warranted. Surgery is reserved for severe symptomatic curves: those more than 50° to 60°.51 With surgery, curves of this magnitude can be improved by approximately 50%.41 The exact surgery performed depends on many factors. However, a spinal fusion with or without Harrington rod instrumentation41 is designed to elongate and stabilize the spine and thereby reduce pain and improve appearance.

Physical therapy after spine fusion for advanced, severe scoliosis requires extensive convalescence, the application of a postoperative brace, and limited activity for up to several weeks after surgery, depending upon the protocol designed by the collaborative efforts of the surgeon and PT.41

THE CERVICAL SPINE

Neck pain is thought to affect up to 66% of the population at least once in a individual’s lifetime.44 The economic burden of neck pain in the form of lost wages, cost of treatment, and workers compensation is high. This cost is second only to low back pain.66 Individuals who experience an episode of neck pain may develop symptoms lasting more than 6 months.4 Neck pain patients are frequently seen in outpatient physical therapy. Jette and associates38 reported 25% of an outpatient physical therapy case load is represented by patients with neck pain. Women are also affected by neck pain more frequently than men.66

Without question, the most profound and catastrophic cervical spine injury is a fracture dislocation resulting in quadriplegia. The description of these spinal injuries is beyond the scope of this chapter. Once an evaluation is completed and a cervical spine fracture or spinal cord compression (myelopathy) is ruled out, patients with neck pain are often diagnosed with nerve root involvement or nonspecific mechanical neck pain. The pathoanatomic cause for neck pain is not identifiable for the majority of patients seen in physical therapy.3 In a sample of healthy people without neck pain, up to 19% demonstrated abnormalities with imaging studies.2 These abnormalities included disc protrusion or extrusion and impingement of the nerve root and spinal cord. The significant prevalence of abnormal findings with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in asymptomatic individuals can lead to medical misdiagnosis.

Whiplash Associated Disorder: Acute Sprains and Strains

Muscular strains of the cervical spine are common among young athletes and in association with motor vehicle accidents with flexion-extension, lateral flexion, and acceleration-deceleration “whiplash” type injuries.59,67 Numerous impairments, stemming from bony and soft tissue injury, can be classified as whiplash associated disorder (WAD).58 The U.S. annual cost associated with WAD is $29 billion.66 The muscles that can be involved in cervical strains are the sternocleidomastoid, trapezius, scalenes, erectors, rhomboids, and levator scapulae.67 The mechanism of injury producing cervical strains and sprains varies but includes hyperflexion, rotation, and lateral flexion of the head and cervical spine.59

Forces usually are great enough with automobile accidents that ligament injuries occur in conjunction with muscle strains. In fact, Stratton and Bryan’s59 experimental studies have demonstrated a wide range of tissue damage with hyperextension type automobile injuries:

1. Tearing of sternocleidomastoid muscle

2. Tearing of longissimus coli muscle

4. Tearing of anterior longitudinal ligament

5. Separation of cartilaginous end plate of the intervertebral disc

Similar types of injuries occur with hyperflexion injuries as a result of automobile accidents59:

1. Tears of the posterior cervical muscles

2. Tears of the ligamentum nuchae

Cervical Radiculopathy

Cervical radiculopathy is defined as mechanical compression or inflammation of a nerve root which causes neurologic symptoms into the upper extremities. Most common causes of radiculopathy are cervical disc herniation, spondylosis, and osteophytes.61 The symptoms of peripheral pain, radicular signs, local cervical pain, and scapular pain are consistent with the symptoms of disc herniations observed in the lumbar spine.59

As with lumbar disc herniations, the initial goals are to relieve symptoms, reduce pain and swelling, control muscle spasm, and work toward centralizing the symptoms. Iglarsh and Snyder-Mackler36 define improvement as “a decrease in the extent or intensity of the peripheral symptoms.” The specific exercises for cervical disc herniation patients must be identified carefully by the physician and PT. Once the appropriate subgrouping of treatment is recognized, the PT organizes a comprehensive plan of pain relief, motion, strength, and postural education activities for the PTA to follow and apply.11

Cervical Spondylosis

In contrast to cervical disc herniations, cervical spondylosis involves chronic rather than acute degenerative disc, which results from “wear and tear on the weight-bearing structures of the cervical spine.”59 The symptoms are characteristic of spinal cord compression (myelopathy) or nerve root compression with radicular signs.51 Cervical spondylosis is seen most often during the fourth and fifth decades of life and characteristically affects men more than women at the C5-C6 and C6-C7 segments.51

Sustained impact loading and repetitive microtrauma59 are causative factors that can produce cervical cord impingement, nerve root impingement, osteophytes, bone sclerosis, loss of cervical lordosis, and central or posterolateral disc herniations.51,59

Initial physical therapy interventions focus on pain relief with the evaluation of thermal and electrical agents, physician-prescribed analgesics, and rest from aggravating positions. As with the evaluation of other disc conditions, the PT provides a comprehensive evaluation to accurately determine which motions cause pain and radicular symptoms and which relieve pain. From this detailed initial evaluation, the PT outlines and describes specific exercises consistent with these findings. In some cases, traction is an effective tool to minimize joint compressive loads and reduce cord compression or nerve root irritation.51,57 The PT determines if mechanical traction or manual cervical traction is more appropriate. Isometric cervical spine stabilization exercises (four-way isometrics) and ROM exercises are initiated once pain has been reduced and the appropriateness of these activities is determined by the PT.

When cord compression (myelopathy) progresses and radicular pain persists, the physician can use various surgical interventions. Miller51 describes an anterior cervical spine approach to accomplish a discectomy and fusion or a posterior approach for a foraminotomy or multilevel laminectomy to relieve cord or root compression.

Cervical Facet Syndrome

The cervical facet joint is another possible source of neck pain.50 Symptoms can include posterior neck stiffness, pain with cervical extension or rotation, cervicogenic headaches, and possible pain referral into the shoulder and scapula.68 Degenerative changes to the cervical facet and surrounding soft tissue may cause this radiation. It is estimated that facet involvement affects 54% to 60% of chronic neck pain patients.47 Appropriate interventions identified by the PT may include pain control, ROM, and exercise.

Thoracic Inlet Syndrome

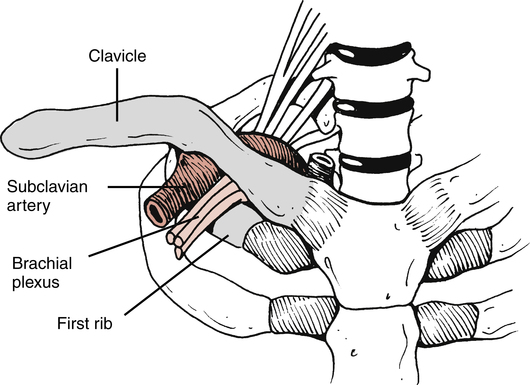

Some texts cover thoracic inlet syndrome within the subject matter affecting the shoulder.69 Because of the anatomic proximity of the structures involved, this condition is discussed within the context of the cervical spine. Authorities point out that the term thoracic inlet syndrome is a more precise and anatomically accurate term used to describe compression of vascular or neurologic tissues as they exit the “superior triangle opening of the thorax” (Fig. 20-17).59,69 (This syndrome has been commonly called outlet syndrome in the past.)Specifically, proximal compression of the subclavian artery and vein, as well as the brachial plexus, are the most probable neurovascular factors involved with thoracic inlet syndrome.59 Many structures can cause compression of these tissues. Foremost is the presence of a cervical rib, a shortened or hypertrophied anterior scalene muscle, or malunion of the clavicle and subluxed first thoracic rib.32,59,69 Symptoms of this condition include radicular signs of pain, numbness, tingling, weakness, and skin and temperature changes consistent with neurovascular tissue compression.32,59,69

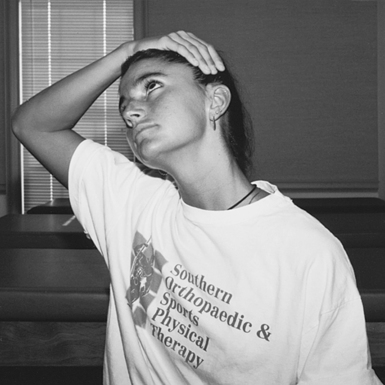

Soft-tissue stretching focuses on the anterior scalene muscles. The patient is instructed to laterally flex and extend the head to the opposite side of the shortened muscle (Fig. 20-18). Thoracic kyphosis tends to accentuate the symptoms of thoracic inlet syndrome, so pectoral stretching (facing an open doorway with hands on either side and leaning forward) and thoracic extension mobility and strengthening exercises are used to specifically address muscle weakness and soft-tissue restrictions. A host of clinically applicable thoracic extension mobility exercises can be used. Examples include seated scapular retraction, prone scapular and thoracic extension, and seated rowing activities with elastic tubing.

In addition to stretching and strengthening exercises, cervical posture correction is needed; poor cervical posture is a common problem in the workplace.32 To address the forward head posture and tight anterior neck muscles, the patient can perform axial extension or cervical retraction stretching exercises, as described.

Treatment Based Classification: Cervical Spine

Effective management of the cervical spine requires a multimodal treatment approach. The cervical spine TBC system assimilates information from the patient history and physical examination to classify the patient for the most appropriate treatment subgroup.13,23 The five subgroups are labeled mobility, centralization, exercise and conditioning, pain control, and headache. As explained earlier, the patient moves fluidly in and out of these subgroupings during the duration of care. Preliminary research has identified that patients experienced improved outcomes when matched to interventions of their treatment subgroup.23

The cervical region is the most mobile region of the spine. Impairments in ROM in one vertebral level will change the motion in adjacent levels. The restoration of mobility in the cervical spine may be the first subgrouping chosen by the PT after the initial evaluation. Interventions may include mobilization, active ROM, passive ROM, and manipulation of the thoracic spine.23 The PT will then initiate exercise in the form of ROM, strength, and conditioning with the PTA. Research suggests patients treated with manual therapy and exercise experience a clinically important reduction in pain.31,35

An important practical matter to consider when instructing patients to perform cervical ROM exercises is how to stabilize the trunk and shoulders. With both muscle and ligament damage, the long-term effect of healing is fibrous tissue contraction, which results in stiffness, restriction, and limitation of motion.67 Therefore to effectively direct the stretch to the affected area, the surrounding structures must be supported and stabilized. For example, if a patient with a lateral flexion injury that results in muscle and ligament damage is instructed to gently stretch laterally away from the side of the injury, the opposite shoulder would elevate (because of the shortened tissues) if the shoulders are not stabilized, rendering the stretch ineffective. To stabilize the shoulder, the patient should perform the stretch while seated and use both hands to grasp under the seat. No shoulder elevation occurs when the patient attempts to stretch the head and neck laterally with the arms fully extended and secured under the seat.

Strengthening and conditioning exercise for the neck and upper quarter include the deep neck flexors. Prevailing theory suggests that stability of the cervical spine is dependent on deep neck flexor strength.39 Jull and co-workers40 reported retraining the deep cervical flexors in conjunction with manual therapy to the cervicothoracic spine can effectively decrease neck pain and headache with results being maintained at 1-year follow-up.15 Precise instruction by the PTA for retraining deep neck flexor is very important for improved patient function.

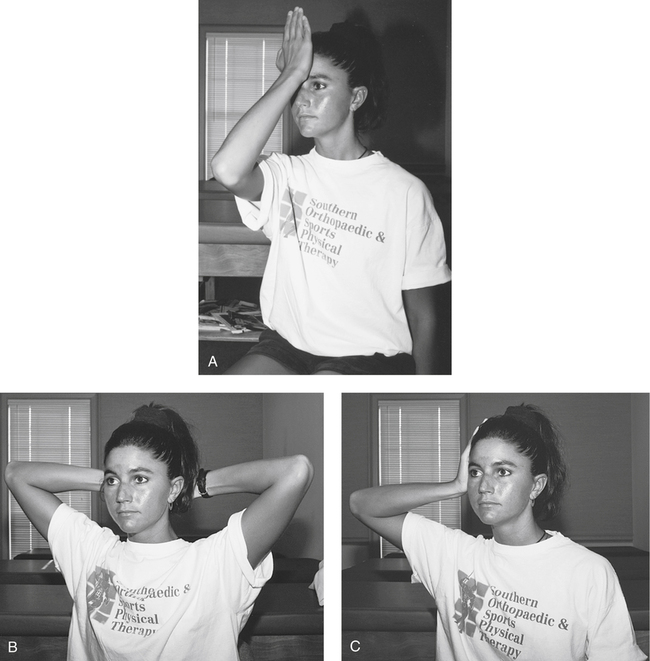

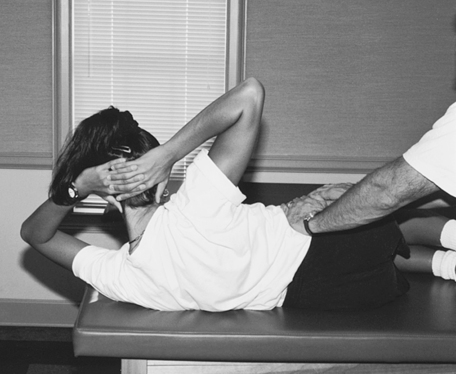

To begin, the patient should sit before a mirror to get visual feedback while maintaining proper head and neck alignment. The proper execution of the first isometric position of forward flexion should be explained and demonstrated. With one hand placed on the midline of the forehead (the patient must bring the hand into the described position and not rotate the head toward the hand), the patient should direct a posterior force to the forehead with the hand while resisting head and neck flexion, thereby stimulating isometric strengthening of the anterior cervical muscles. The patient should gradually and slowly build the resistance using the rule of 10s (gradually initiate isometrics with 2-second submaximal contraction, then hold for 6 seconds, then slowly reduce for 2 seconds) rather than suddenly applying maximal force (Fig. 20-19, A).

The patient should use both hands to support the occiput for the second position. The patient should maintain the head and neck in the anatomic midline position and not allow the head to flex forward. The patient should be encouraged to gradually apply an anteriorly directed force with both hands while resisting extension of the head. This position effectively strengthens the head and neck extensor group (Fig. 20-19, B).

The next position is lateral flexion. While the PTA observes proper head and neck alignment in the mirror, the patient should bring one hand to the side of the head but not allow the head to rotate or laterally flex to meet the hand. The patient should then apply lateral pressure while resisting this force. This position is repeated on the opposite side. No head or neck motion must occur in each position. Usually the patient carries out a series of two to three sets of 10-second isometric exercises two to three times daily. As strength improves, the patient gradually increases the intensity, but avoids sudden or ballistic contractions (Fig. 20-19, C).

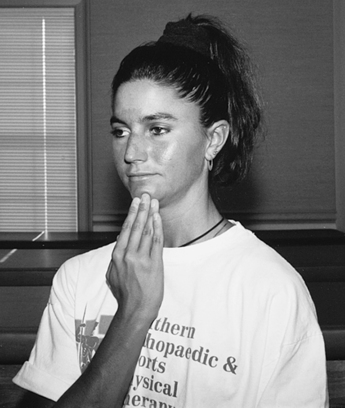

The PT may determine that the patient responds to repeated movements in a specific directional preference. A centralization phenomenon may occur where distal symptoms in the upper quarter decrease or abolish and symptoms increase or present near the central location of the cervical spine. The patient often responds to repeated retraction exercises in supine and sitting positions. Retraction exercises require the patient to be able to demonstrate a midline neutral position. The patient should sit in front of a mirror initially to perform this exercise correctly. Have the patient imagine that his or her head is resting on a conveyor belt. The patient must be able to align the ears with the shoulders and move the head straight back on the conveyor belt (Fig. 20-20). If done correctly, a “double chin” is produced as the patient moves the head back. If done incorrectly, the head and neck move into extension. The patient should be encouraged to perform this exercise at home for multiple sets throughout the day or as prescribed by the PT.

Upper Limb Neurodynamic Tension Test A: Median Nerve Bias

The upper limb tension test is assessed by placing the patient in the following positions:

Impairments in ROM and strength are frequently accompanied by pain. Pain control subgrouping will include those patients with high pain and disability scores noted on outcome measures. They may have been involved in a traumatic event or report very recent onset of symptoms. In many cases, these patients will present with poor tolerance to interventions and possibly elevated fear avoidance beliefs noted on the on the FABQ.28

Mobilization of the Lumbar, Thoracic, and Cervical Spine

GLOSSARY

Disc protrusion Condition in which nucleus bulges against an intact annulus.

Lordosis The maintenance of a normal anatomic lordotic curve while lifting any object.

Nucleus pulposus The [fiber/substance/gel] contained within the annulus.

Scoliosis A disorder defined as any lateral curvature of the cervical, thoracic, or lumbar spine. It can be classified as either structural or nonstructural.41