19 Orthopaedics

Clinical assessment

History

Other key points to ascertain in the history include:

• occupation and right/left handedness

• past trauma (may cause osteoarthritis)

• interference with daily living (e.g. stiff arthritic hip making it difficult to put on shoes or cut toenails)

• requirement for aid (e.g. walking stick or special cutlery)

• severity of pain (night pain may indicate severe arthritis requiring joint replacement).

Examination

Look at the gait (Box 19.1), skin for scars and colour, and the general shape of the joint, swelling, lumps and position. Feel for temperature, tenderness, crepitus, loose bodies, swelling (fluid, soft tissue or bone). Measure limb lengths where appropriate. Move the limb, asking the patient to move it first to determine the range of active movements before ascertaining passive movements.

Box 19.1 Abnormal gaits

Antalgic: Painful and with a short stance phase; seen in any condition of the lower leg where the pain is exacerbated by weight-bearing, e.g. osteoarthritis of the hip

Stiff leg: A fused hip or knee joint causes abnormal swing-through when the pelvis has to be rotated to bring the leg through

Trendelenburg: With proximal muscle weakness the pelvis on the opposite side sags during the stance phase – seen in developmental dysplasia of the hip, poliomyelitis and in osteoarthritis of the hip

Short leg: During the stance phase, the short leg results in the pelvis and shoulder on the affected side sagging down

Shuffling: Seen in Parkinson’s disease, it has a short swing-through and no real heel strike or toe off

Stamping: The swing-through phase is abnormal with a broad base and high stepping – often caused by peripheral neuropathy with tabes dorsalis

Ataxic: Broad-based with unsteadiness on turning – cerebellar disease, multiple sclerosis or head injury

Foot drop: During swing-through, the foot scuffs on the ground – an L5 root lesion, common peroneal nerve palsy or old poliomyelitis

Scissor: Occurs in children with cerebral palsy with adductor spasm, so the swing-through of one leg is blocked by the other

Investigation

Imaging

Investigations useful in imaging orthopaedic problems are summarised in Table 19.1.

| Test | Indication | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Plain X-rays | Excellent definition of most bony and some soft tissue problems | Osteoarthritis: four radiological features are loss of joint space, osteophyte formation, bone cysts and subchondral bone sclerosis |

| Arthrography | Injection of contrast into a joint space demonstrates capsule abnormalities and loose bodies | Rotator cuff tears of the shoulder |

| Tomography | Now of limited use, replaced by CT and MRI | Mandible and teeth (orthopantogram) |

| CT | Detailed information on complex bony lesions | Spine, bone tumours, pelvic fractures, fractures involving joint surfaces |

| MRI | Provides excellent detail of bone and soft tissue lesions | Spinal cord, knee |

| Isotope scanning | Technetium-99 labelled biphosphonate is concentrated in areas of increased osteoblastic activity including infected and malignant bone | Prosthetic infection, bone metastases |

Osteoarthritis (OA)

Septic arthritis and osteomyelitis

Acute osteomyelitis

This is now rare in adults who are not immunocompromised or diabetic. Young children are more commonly affected. The likely culprit organisms are summarised in Box 19.2.

Chronic osteomyelitis

This may follow unsuccessful treatment of acute osteomyelitis or an open compound fracture, or may be a consequence of an infected joint replacement. The condition may be complicated by pathological fracture, amyloidosis and malignant change (squamous cell carcinoma in a sinus tract). Well-recognised versions of chronic osteomyelitis are summarised in Box 19.3.

Box 19.3 Recognised types of chronic osteomyelitis

Complication of acute osteomyelitis – prevent with prompt treatment of acute infection

Complication of open compound fracture – prevent by early appropriate treatment of compound fractures

Infected joint replacement arthroplasty

Tuberculosis – now less rare, when seen in the spine may lead to vertebral collapse and cord compression (Pott’s paraplegia). Immunosuppressed patients at higher risk

Mycotic infection – long bones and spine

Syphilis – now rare. Congenital syphilis causes infection of the growth plates

Brodie’s abscess – well-defined walled-off abscess in long bone (usually from acute osteomyelitis)

Tumours of bone

Signs of bone tumours

Search for a primary tumour. A bony lump may be palpable, which may be tender.

Primary bone tumours

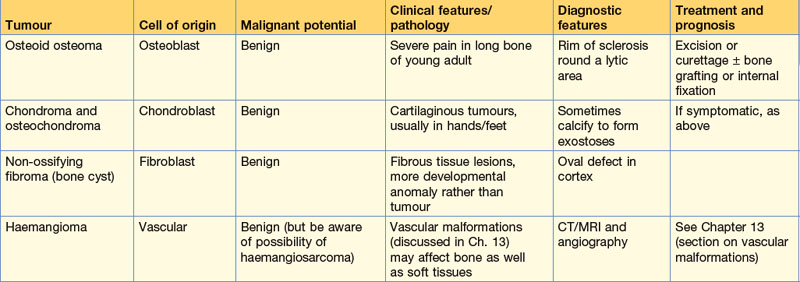

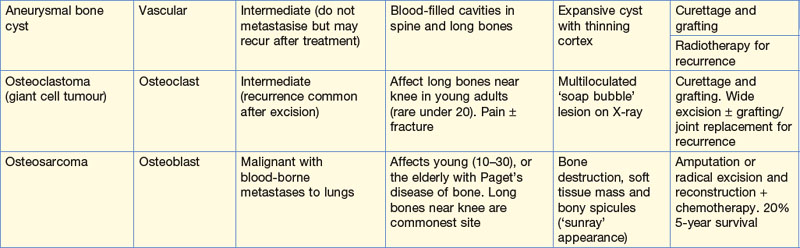

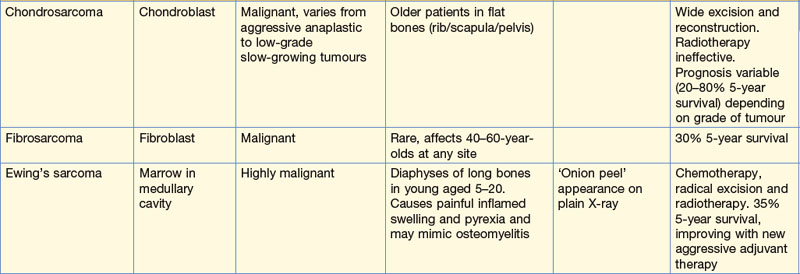

Primary bone tumours are not always easily classified as benign or malignant: there is an intermediate group which are locally invasive but do not metastasise. Distinguishing benign from intermediate and more dangerous lesions may be problematic. In contrast to bony metastases, malignant primary bone tumours are rare, with fewer than 500 cases per year in the UK. The characteristics of primary bone tumours are summarised in Table 19.2.

Upper limb

Shoulder

Symptoms

Investigation

• Plain X-rays: demonstrate arthritis and abnormal calcification.

• Arthrography: now superseded by MRI but commonly used in the past to demonstrate rotator cuff tears (supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, subscapularis) by leakage of contrast into the subacromial bursa.

• CT/MRI: of increasing value.

• Arthroscopy: both diagnostic and therapeutic; it is possible to remove loose bodies, decompress the subacromial space and stabilise the shoulder in recurrent dislocation.

Common problems

The hands

How to examine hands

Neurological function

Test the median, ulnar and radial nerves.

If deficits are detected, look for scars of previous trauma as suggested in Table 19.3.

Table 19.3 Sites of causes of neurological deficits in the hand

| Abnormality | Possible anatomic site/cause |

|---|---|

| Median nerve palsy | Carpal tunnel syndromeOperations on antecubital fossa |

| Ulnar nerve palsy | Operations/trauma near medial epicondyle |

| Radial nerve palsy | Nerve vulnerable in spiral groove of humerus: look for evidence of arm injury |

| Combination of more than one nerve | Consider: Brachial plexus injury (birth trauma or motorcycle accident) Spinal root lesion (if sensory loss is dermatomal) Stroke |

Disorders of the hand

Carpal tunnel syndrome

Spine

Low back pain

Causes

The causes of low back pain are summarised in Box 19.4. Although debilitating, most cases are due to a combination of degeneration and trauma and will settle. Only a small but important minority require surgery, mostly for nerve root decompression to relieve referred pain down the leg (sciatica). A careful history and examination is necessary to make a diagnosis of the cause. Several of the mechanical causes of back pain result in severe muscle spasm, explaining the flare-ups of a chronic problem that many patients experience.

History

Mechanical pain is usually intermittent. Constant pain suggests a more serious (infective or malignant) cause. Pain on coughing and sneezing is commonly due to disc prolapse. A detailed history may narrow the differential diagnosis outlined in Box 19.4.

Intervertebral disc prolapse

The L5/S1 disc compressing the S1 nerve root is the commonest prolapsed disc. The one above (L4–5 compressing the L5 root) is next. The pain is severe, radiating down the back of the leg (sciatica) into the appropriate dermatome, exacerbated by coughing and sneezing, and straight leg raising. Muscle spasm limits movements. Disturbance of sphincter function is an important symptom indicating a large disc prolapse likely to need surgical treatment. Table 19.4 highlights the signs of the two commonest types of disc prolapse.

| L5 | S1 (the commonest) |

|---|---|

| Pins and needles and reduced sensation in L5 dermatome (includes dorsum of foot, hallux and second toe) | Pins and needles and reduced sensation in S1 dermatome (includes lateral thigh and calf and lateral three toes) |

| Weak extensor hallucis longus | Weak plantarflexion of ankle |

| Weak dorsiflexion of ankle (tibialis anterior) | Weak eversion of ankle |

| Wasting of extensor digitorum brevis | Absent/diminished ankle jerk reflex |

Lower limb

Osteoarthritis of the hip

Examination

Look

Feel

• Measure true and apparent limb length. The apparent length is measured from the umbilicus to the medial malleoli with the patient lying flat. True length is measured from the anterior superior iliac spine to the medial malleoli. If the affected limb is fixed in an abnormal position of abduction or adduction, the opposite limb must be placed in a symmetrical position to make the true measurement.

The knee

Knee haemarthrosis

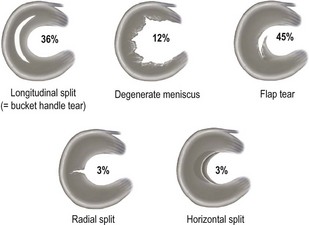

Many acute knee injuries cause bleeding into the joint which causes tense, painful swelling (haemarthrosis). Some will settle with rest and elevation but early arthroscopy allows the blood to be washed out and the precise injury to be diagnosed. The causes of acute knee haemarthrosis are listed in Table 19.5.

| Lesion | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Anterior cruciate ligament rupture | 39 |

| Peripheral meniscal tear | 26 |

| Collateral ligament injury | 13 |

| Capsular tear | 9 |

| Osteochondral fracture | 7 |

| Posterior cruciate ligament rupture | 6 |

Seventy per cent have more than one lesion, 29% have only one lesion, and in 1% no cause is found.

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries

Examination detects only 70% of ACL ruptures; the remainder require MRI.

Hip disorders in children

Table 19.6 summarises the age ranges for the common hip disorders found in children.

Table 19.6 Age ranges for the common hip disorders found in children

| Age | Condition |

|---|---|

| 0–5 years | Developmental dysplasia of the hip (formerly known as congenitally dislocated hip) |

| 5–10 years | Perthes’ disease |

| 10–15 years | Slipped upper femoral epiphysis |

Developmental dysplasia of the hip (previously called congenitally dislocated hip)

Hip instability at or soon after birth due to an underdeveloped acetabulum and ligamentous laxity is known as developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH). The incidence is around 1 per 1000 live births and is four times commoner in females; 60% of cases involve the left hip, 20% right and 20% are bilateral (bilateral DDH is particularly difficult to diagnose). Risk factors for DDH are summarised in Box 19.5.

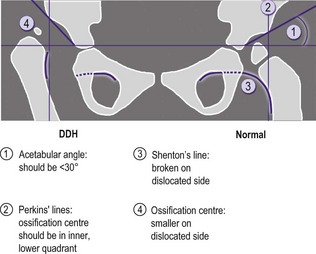

Investigation for DDH

The most frequently identified radiological signs of DDH are summarised in Figure 19.2. Ultrasound may also be diagnostic especially in the neonate.

Irritable hip

This very common condition affecting children aged 2–12 years causes hip pain and a limp. The cause is unknown but postulated to be viral. Irritable hip is self-limiting and benign, but is a diagnosis that can only be made when more serious conditions (Box 19.6) have been excluded.

Fractures

Classification of fractures

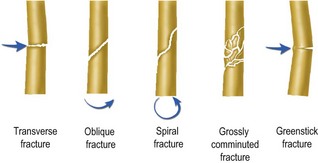

A classification of fractures is described in Figure 19.3. A comminuted fracture is one with more than two bone fragments. Grossly comminuted fractures are usually associated with extensive soft tissue injury. Greenstick fractures occur in children whose bones are more flexible.

Fracture healing

Factors predisposing to poor fracture healing

Factors impairing healing of wounds including fractures are listed in Box 2.1, p. 14.

Delayed union

Healing is considered delayed if union has not occurred within 1.5 times the normal time frame.

Non-union

The fracture fails to heal within twice the normal time frame. There are two types of non-union: hypertrophic, due to inadequate immobilisation (the bone ends look like opposing elephants’ feet) and atrophic, usually due to poor blood supply (the bone ends look sclerotic). The scaphoid bone is a good example of a bone notorious for non-union. In Figure 19.5 there is a radiological gap between the fragments that can be assumed to be filled with fibrous tissue. There is some, although not much, evidence of sclerosis.

Principles of fracture management

Treatment of fractures requires:

Immobilisation

Immobilisation relieves pain and prevents excessive movement at the fracture site which would impair healing. Some fractures, e.g. rib injuries, are held in place by surrounding structures and heal without immobilisation. Other bones require rigid fixation to heal, e.g. scaphoid and shaft of ulna. Methods of fracture immobilisation are summarised in Box 19.7.

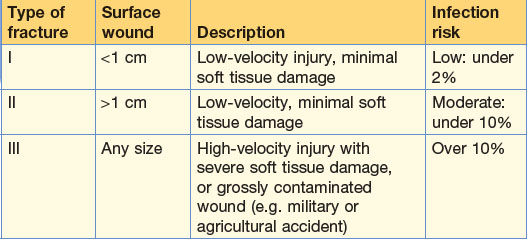

Open fractures

Open (compound) fractures are surgical emergencies because of risk of infection of the fractured bone. If the bone becomes infected, chronic osteomyelitis results, which may prevent union and even threaten the limb. Open fractures are classified as shown in Table 19.7.