Orthopaedic tumors and masses

Introduction

Orthopaedic oncology is a field of orthopaedic surgery that specializes in the diagnosis and treatment of both benign and malignant tumors of the bones and soft tissues of the extremities, pelvis, and spine. Although definitions vary, a tumor can be thought of simply as any mass in the soft tissues or bone that otherwise should not be there. For example, a tumor may be a neoplasm, which is an abnormal proliferation of abnormal cells; a hamartoma, which is an abnormal proliferation of normal cells; or simply an infection causing a masslike effect. The focus of this chapter will be the common neoplasms encountered by the musculoskeletal oncologist.

Orthopaedic oncology is a field of orthopaedic surgery that specializes in the diagnosis and treatment of both benign and malignant tumors of the bones and soft tissues of the extremities, pelvis, and spine. Although definitions vary, a tumor can be thought of simply as any mass in the soft tissues or bone that otherwise should not be there. For example, a tumor may be a neoplasm, which is an abnormal proliferation of abnormal cells; a hamartoma, which is an abnormal proliferation of normal cells; or simply an infection causing a masslike effect. The focus of this chapter will be the common neoplasms encountered by the musculoskeletal oncologist.

Musculoskeletal neoplasms can first be divided into benign and malignant entities. Benign neoplasms are proliferations of abnormal cells that have no potential to metastasize to other areas of the body. Locally, some benign neoplasms can be aggressive and cause significant problems. However, despite its local activity, if a neoplasm has the ability to travel to a distant organ (such as the lungs or lymph nodes) it is considered malignant.

Musculoskeletal neoplasms can first be divided into benign and malignant entities. Benign neoplasms are proliferations of abnormal cells that have no potential to metastasize to other areas of the body. Locally, some benign neoplasms can be aggressive and cause significant problems. However, despite its local activity, if a neoplasm has the ability to travel to a distant organ (such as the lungs or lymph nodes) it is considered malignant.

Malignant bone disease

There are many categories of malignant neoplasms. Some of these include carcinomas (from epithelial origin), adenocarcinomas (from epithelial cells with secretory properties), lymphomas (arising from lymphocytes), leukemia (from bone marrow cells), and melanomas (from transformed melanocytes). A sarcoma is a malignant neoplasm that arises from cells of mesenchymal origin. Mesenchymal tissues include those found in the limbs and pelvis: bone, cartilage, muscle, fat, vessels, and nerves. Sarcomas are exceedingly rare. Every year in the United States there are fewer than 10,000 new cases of bone sarcoma and fewer than 15,000 new soft tissue sarcomas.

There are many categories of malignant neoplasms. Some of these include carcinomas (from epithelial origin), adenocarcinomas (from epithelial cells with secretory properties), lymphomas (arising from lymphocytes), leukemia (from bone marrow cells), and melanomas (from transformed melanocytes). A sarcoma is a malignant neoplasm that arises from cells of mesenchymal origin. Mesenchymal tissues include those found in the limbs and pelvis: bone, cartilage, muscle, fat, vessels, and nerves. Sarcomas are exceedingly rare. Every year in the United States there are fewer than 10,000 new cases of bone sarcoma and fewer than 15,000 new soft tissue sarcomas.

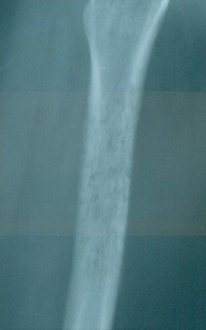

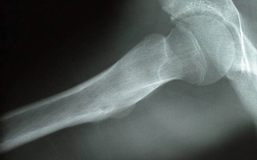

Malignant bone disease often causes bone destruction or lysis. A permeative or moth-eaten pattern of lysis (Fig. 10-1), in which the bone is aggressively destroyed with indistinct margins, is usually displayed. A more geographic pattern, in which there is a clear margin between normal and abnormal bone, is seen with benign tumors (Fig. 10-2).

Malignant bone disease often causes bone destruction or lysis. A permeative or moth-eaten pattern of lysis (Fig. 10-1), in which the bone is aggressively destroyed with indistinct margins, is usually displayed. A more geographic pattern, in which there is a clear margin between normal and abnormal bone, is seen with benign tumors (Fig. 10-2).

Metastatic disease

Metastatic carcinoma to bone is 25 times more likely to occur than primary bone sarcoma. The five primary carcinomas that most commonly metastasize to bone are breast, prostate, lung, kidney, and thyroid. In contrast to the small numbers of primary bone sarcoma, there are more than a million new cases of these five carcinomas in the United States every year. Metastatic carcinoma most commonly occurs in the thoracic and lumbar spine (theoretically because of the valveless Batson”s venous system there) but can occur in virtually any bone. It commonly presents as pain and can lead to weakened bone and pathologic fractures (fractures that occur at normal physiologic loads).

Metastatic carcinoma to bone is 25 times more likely to occur than primary bone sarcoma. The five primary carcinomas that most commonly metastasize to bone are breast, prostate, lung, kidney, and thyroid. In contrast to the small numbers of primary bone sarcoma, there are more than a million new cases of these five carcinomas in the United States every year. Metastatic carcinoma most commonly occurs in the thoracic and lumbar spine (theoretically because of the valveless Batson”s venous system there) but can occur in virtually any bone. It commonly presents as pain and can lead to weakened bone and pathologic fractures (fractures that occur at normal physiologic loads).

Metastatic breast cancer is common in women with advanced disease. Radiographically, it is classically a mixed lytic and blastic lesion; that is, it causes lysis of bone and formation of bone (Fig. 10-3). It typically responds to radiation therapy but commonly requires surgical stabilization. Metastatic prostate cancer is also radiosensitive but typically is a purely blastic process (Fig. 10-4). Lung, kidney, and thyroid disease usually cause purely lytic and destructive lesions (Fig. 10-5). Renal cell carcinoma and thyroid disease are extremely vascular lesions that often require embolization before open surgical treatment.

Metastatic breast cancer is common in women with advanced disease. Radiographically, it is classically a mixed lytic and blastic lesion; that is, it causes lysis of bone and formation of bone (Fig. 10-3). It typically responds to radiation therapy but commonly requires surgical stabilization. Metastatic prostate cancer is also radiosensitive but typically is a purely blastic process (Fig. 10-4). Lung, kidney, and thyroid disease usually cause purely lytic and destructive lesions (Fig. 10-5). Renal cell carcinoma and thyroid disease are extremely vascular lesions that often require embolization before open surgical treatment.

Because of the overwhelming preponderance of potentially metastatic carcinoma, any lytic bone lesion in a patient older than 40 years of age should be considered metastatic disease until proven otherwise. Workup for these patients should include radiographs of the entire affected bone, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the area to assess soft tissue extent, a bone scan to assess other skeletal disease, and a computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis in an attempt to identify the primary site (Fig. 10-6). Often a biopsy will still be necessary to secure a definitive tissue diagnosis.

Because of the overwhelming preponderance of potentially metastatic carcinoma, any lytic bone lesion in a patient older than 40 years of age should be considered metastatic disease until proven otherwise. Workup for these patients should include radiographs of the entire affected bone, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the area to assess soft tissue extent, a bone scan to assess other skeletal disease, and a computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis in an attempt to identify the primary site (Fig. 10-6). Often a biopsy will still be necessary to secure a definitive tissue diagnosis.

Surgical treatment of metastatic disease can be challenging. Painful lesions in weight-bearing bones should be aggressively stabilized, but many lesions may not have definite surgical indications, especially in patients with limited life spans. A team approach with medical oncology, radiation oncology, orthopaedic oncology, and the patient should be used to optimize treatment and outcomes. Unfortunately, bone metastasis is an ominous finding with little chance of cure.

Surgical treatment of metastatic disease can be challenging. Painful lesions in weight-bearing bones should be aggressively stabilized, but many lesions may not have definite surgical indications, especially in patients with limited life spans. A team approach with medical oncology, radiation oncology, orthopaedic oncology, and the patient should be used to optimize treatment and outcomes. Unfortunately, bone metastasis is an ominous finding with little chance of cure.

Although much rarer, other malignancies such as melanoma, colon, bladder, and cervical cancer can all metastasize to bone and should be suspected in patients with a positive medical history. Metastatic bone disease in children is not common but can be seen with neuroblastoma and Wilms tumor.

Although much rarer, other malignancies such as melanoma, colon, bladder, and cervical cancer can all metastasize to bone and should be suspected in patients with a positive medical history. Metastatic bone disease in children is not common but can be seen with neuroblastoma and Wilms tumor.

Multiple myeloma

Multiple myeloma, a malignant disease of monoclonal plasma cells, is the second most common cause of lytic lesions in adults. It is more common in men in their 60s and in African Americans. The bone lesions are well-defined, punched-out lytic areas that can be seen in any bone (Fig. 10-7) and are often seen in the skull. Patients will often have anemia (from bone marrow replacement by tumor), hypercalcemia (from the bone lysis), and a monoclonal protein spike on urine and serum protein electrophoresis. Treatment is multimodal, requiring medical oncology, radiation oncology, and orthopaedics.

Multiple myeloma, a malignant disease of monoclonal plasma cells, is the second most common cause of lytic lesions in adults. It is more common in men in their 60s and in African Americans. The bone lesions are well-defined, punched-out lytic areas that can be seen in any bone (Fig. 10-7) and are often seen in the skull. Patients will often have anemia (from bone marrow replacement by tumor), hypercalcemia (from the bone lysis), and a monoclonal protein spike on urine and serum protein electrophoresis. Treatment is multimodal, requiring medical oncology, radiation oncology, and orthopaedics.

Lymphoma

Metastatic disease and multiple myeloma account for the vast majority of malignant lesions of bone in adults and should be the first and second entities on any differential diagnosis. Lymphoma that arises primarily in bone, although rare, can also be seen. It is often in younger and middle-age adults and classically has a large soft tissue mass with little bony change or destruction. Surgery for lymphoma of bone is for biopsy and bone stabilization only; definitive treatment with high cure rates is a combination of chemotherapy and radiation.

Metastatic disease and multiple myeloma account for the vast majority of malignant lesions of bone in adults and should be the first and second entities on any differential diagnosis. Lymphoma that arises primarily in bone, although rare, can also be seen. It is often in younger and middle-age adults and classically has a large soft tissue mass with little bony change or destruction. Surgery for lymphoma of bone is for biopsy and bone stabilization only; definitive treatment with high cure rates is a combination of chemotherapy and radiation.

Primary sarcoma of bone

Except for chondrosarcoma (which is seen almost exclusively in adults) the primary sarcomas of bone occur more commonly in the pediatric population. Therefore, entities like osteosarcoma and chondrosarcoma should be considered at the bottom of the differential diagnosis of malignant bone lesions in adults (behind metastatic disease, multiple myeloma, and lymphoma). Primary sarcoma should be at the top of the differential diagnosis of aggressive lesions in children. The primary sarcomas below account for the most common entities.

Except for chondrosarcoma (which is seen almost exclusively in adults) the primary sarcomas of bone occur more commonly in the pediatric population. Therefore, entities like osteosarcoma and chondrosarcoma should be considered at the bottom of the differential diagnosis of malignant bone lesions in adults (behind metastatic disease, multiple myeloma, and lymphoma). Primary sarcoma should be at the top of the differential diagnosis of aggressive lesions in children. The primary sarcomas below account for the most common entities.

Secondary sarcomas of bone are rarely seen but should be considered when there is a lytic lesion or a mass in a bone with preexisting Paget”s disease or previous radiation therapy (osteosarcoma is the most common variant). Enchondromas and osteochondromas can transform into chondrosarcomas less than 1% of the time. Rarely, secondary sarcomas can arise from bone infarcts or fibrous dysplasia.

Secondary sarcomas of bone are rarely seen but should be considered when there is a lytic lesion or a mass in a bone with preexisting Paget”s disease or previous radiation therapy (osteosarcoma is the most common variant). Enchondromas and osteochondromas can transform into chondrosarcomas less than 1% of the time. Rarely, secondary sarcomas can arise from bone infarcts or fibrous dysplasia.

Osteosarcoma

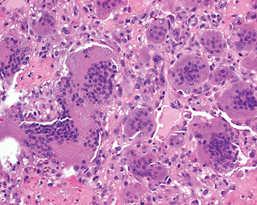

Osteosarcoma is the most common primary sarcoma of bone. It is a high-grade disease that has a bimodal age distribution; it arises mostly in children but also in the elderly (often secondary to a preexisting condition like Paget”s disease). It can occur in any bone but is most common around the knee. Radiographically, it is classically a mixed lytic and blastic lesion with a soft tissue mass characterized by a “sunburst,” radial pattern of osteoid formation (Fig. 10-8). Pathologically, the tumor is required to have malignant cells producing osteoid (Fig. 10-9).

Osteosarcoma is the most common primary sarcoma of bone. It is a high-grade disease that has a bimodal age distribution; it arises mostly in children but also in the elderly (often secondary to a preexisting condition like Paget”s disease). It can occur in any bone but is most common around the knee. Radiographically, it is classically a mixed lytic and blastic lesion with a soft tissue mass characterized by a “sunburst,” radial pattern of osteoid formation (Fig. 10-8). Pathologically, the tumor is required to have malignant cells producing osteoid (Fig. 10-9).

Figure 10-9. High-power view of osteosarcoma. Malignant cells are evident among the pink bands of osteoid.

The workup for osteosarcoma should include an MRI of the entire bone to assess tumor extent (Fig. 10-10), assist with preoperative planning, and rule out any skip metastases (anatomically separate areas of tumor in the same bone); a CT scan of the chest to evaluate the lungs for metastatic disease (the most common site); and a bone scan to evaluate the skeleton (the second most common site of metastatic disease). A biopsy performed by the treating physician is the next step to secure the diagnosis.

The workup for osteosarcoma should include an MRI of the entire bone to assess tumor extent (Fig. 10-10), assist with preoperative planning, and rule out any skip metastases (anatomically separate areas of tumor in the same bone); a CT scan of the chest to evaluate the lungs for metastatic disease (the most common site); and a bone scan to evaluate the skeleton (the second most common site of metastatic disease). A biopsy performed by the treating physician is the next step to secure the diagnosis.

Treatment for osteosarcoma is typically multidrug chemotherapy, followed by wide excision of the lesion (80% to 90% of cases are limb salvage; see Fig. 10-11), followed by more chemotherapy. Five-year survival rates are currently approaching 80%. Chemotherapy can have ototoxic and cardiotoxic side effects.

Treatment for osteosarcoma is typically multidrug chemotherapy, followed by wide excision of the lesion (80% to 90% of cases are limb salvage; see Fig. 10-11), followed by more chemotherapy. Five-year survival rates are currently approaching 80%. Chemotherapy can have ototoxic and cardiotoxic side effects.

Figure 10-11. The gross specimen from Figure 10-8 after chemotherapy and limb salvage surgery.

Ewing’s sarcoma

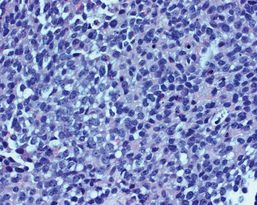

Ewing’s sarcoma is the second most common primary sarcoma in children. Pathologically, it is a high-grade tumor composed of monotonous, small round blue cells (Fig. 10-12). The majority of Ewing”s sarcomas have a characteristic t(11,22) translocation that results in the formation of the EWS-FLI1 oncogene.

Ewing’s sarcoma is the second most common primary sarcoma in children. Pathologically, it is a high-grade tumor composed of monotonous, small round blue cells (Fig. 10-12). The majority of Ewing”s sarcomas have a characteristic t(11,22) translocation that results in the formation of the EWS-FLI1 oncogene.

Ewing’s sarcoma is often seen in flat bones and the metaphyseal-diaphyseal regions of long bones. Classically, it has an “onion skin” appearance (multiple thin layers of periosteal reaction at the site of the tumor; see Fig. 10-13). The workup for Ewing sarcoma is the same as for osteosarcoma, but the prognosis is slightly worse. Treatment involves chemotherapy and local treatment. Most tumors are surgically excised, but because Ewing sarcoma is sensitive to radiation, it can be used to treat tumors that are otherwise unresectable.

Ewing’s sarcoma is often seen in flat bones and the metaphyseal-diaphyseal regions of long bones. Classically, it has an “onion skin” appearance (multiple thin layers of periosteal reaction at the site of the tumor; see Fig. 10-13). The workup for Ewing sarcoma is the same as for osteosarcoma, but the prognosis is slightly worse. Treatment involves chemotherapy and local treatment. Most tumors are surgically excised, but because Ewing sarcoma is sensitive to radiation, it can be used to treat tumors that are otherwise unresectable.

Chondrosarcoma

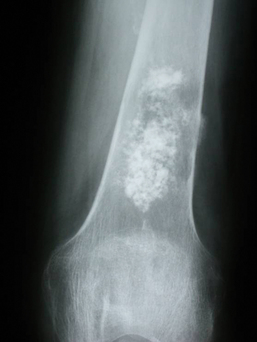

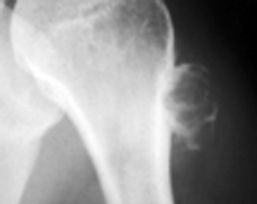

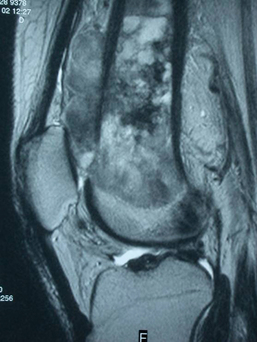

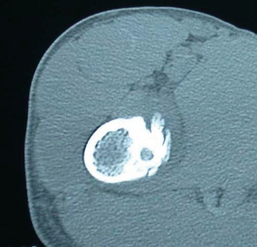

Chondrosarcoma is a primary bone tumor of chondroid origin. Except for clear cell chondrosarcoma (a rare variant seen in the epiphysis of younger patients), chondrosarcomas are seen almost exclusively in adults. They can range from low-grade (grades 1 and 2) to aggressive, high-grade (3) tumors. On radiographs (especially with lower-grade lesions) they often display the punctate calcifications and rings and whorls classic for cartilaginous tissue. They sometimes arise from preexisting benign cartilaginous tumors like enchondromas (Figs. 10-14 and 10-15) and osteochondromas.

Chondrosarcoma is a primary bone tumor of chondroid origin. Except for clear cell chondrosarcoma (a rare variant seen in the epiphysis of younger patients), chondrosarcomas are seen almost exclusively in adults. They can range from low-grade (grades 1 and 2) to aggressive, high-grade (3) tumors. On radiographs (especially with lower-grade lesions) they often display the punctate calcifications and rings and whorls classic for cartilaginous tissue. They sometimes arise from preexisting benign cartilaginous tumors like enchondromas (Figs. 10-14 and 10-15) and osteochondromas.

Figure 10-15. Sagittal magnetic resonance image showing the anterior soft tissue mass of the chondrosarcoma from Figure 10-14.

Chondrosarcomas can arise in any bone and are often seen in the pelvis, where they carry a worse prognosis. The workup for a chondrosarcoma includes an MRI of the affected area, a bone scan, and a chest CT. Chondrosarcomas are not responsive to chemotherapy or radiation, so wide surgical excision is the treatment of choice.

Chondrosarcomas can arise in any bone and are often seen in the pelvis, where they carry a worse prognosis. The workup for a chondrosarcoma includes an MRI of the affected area, a bone scan, and a chest CT. Chondrosarcomas are not responsive to chemotherapy or radiation, so wide surgical excision is the treatment of choice.

Benign bone tumors

Benign tumors are much more common than malignant bony disease. Benign tumors are characterized by a geographic pattern of bone destruction and often have a well-defined rim of reactive bone around the lesion, “walling it off.” According to the Enneking/Musculoskeletal Tumor Society staging system, they can be stage 1 or latent lesions, which are asymptomatic and often found incidentally; they can be stage 2 or active lesions, which are symptomatic and usually require treatment; or they can be stage 3 or aggressive lesions, which can mimic a malignant tumor with local destruction and activity.

Benign tumors are much more common than malignant bony disease. Benign tumors are characterized by a geographic pattern of bone destruction and often have a well-defined rim of reactive bone around the lesion, “walling it off.” According to the Enneking/Musculoskeletal Tumor Society staging system, they can be stage 1 or latent lesions, which are asymptomatic and often found incidentally; they can be stage 2 or active lesions, which are symptomatic and usually require treatment; or they can be stage 3 or aggressive lesions, which can mimic a malignant tumor with local destruction and activity.

Benign tumors can be classified into bone forming, cartilage forming, and others. Careful examination of plain radiography can reveal clues to the lesion’s histology and help in subclassifying and diagnosing the tumor. An MRI is then used to define the anatomic extent of disease and aid in preoperative planning.

Benign tumors can be classified into bone forming, cartilage forming, and others. Careful examination of plain radiography can reveal clues to the lesion’s histology and help in subclassifying and diagnosing the tumor. An MRI is then used to define the anatomic extent of disease and aid in preoperative planning.

Benign bone-forming tumors

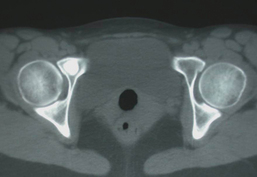

A bone island, or enostosis, is a benign formation of histologically normal cortical bone that is usually seen as an incidental finding on radiography done for other reasons. Enostoses are commonly seen in the pelvis bones on CT scans (Fig. 10-16). Typically, they are small punctate areas of dense bone. They may have mild activity on bone scan. Rarely, they can become large or symptomatic. Treatment is benign neglect. An autosomal dominant disorder in which multiple bone islands can be seen is called osteopoikolosis or spotted bone disease.

A bone island, or enostosis, is a benign formation of histologically normal cortical bone that is usually seen as an incidental finding on radiography done for other reasons. Enostoses are commonly seen in the pelvis bones on CT scans (Fig. 10-16). Typically, they are small punctate areas of dense bone. They may have mild activity on bone scan. Rarely, they can become large or symptomatic. Treatment is benign neglect. An autosomal dominant disorder in which multiple bone islands can be seen is called osteopoikolosis or spotted bone disease.

Osteiod osteoma

Osteoid osteoma is a benign bone tumor seen in young people (usually teenagers) presenting as pain, worse at night, that responds to nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. The actual tumor is a small nidus composed of osteoblasts and osteoid that creates a reactive area of dense cortical bone easily identified on plain films and CT scan (Figs. 10-17 and 10-18). They often occur around the proximal femur and acetabulum but can occur in any bone. They often arise in the posterior elements of the spine, where they are the most common cause of painful scoliosis (found on the concave side at the apex of the curve). The natural history is to gradually burn out, so long-term treatment with NSAIDs is an option, but most patients choose a radiofrequency ablation of the nidus with good results.

Osteoid osteoma is a benign bone tumor seen in young people (usually teenagers) presenting as pain, worse at night, that responds to nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. The actual tumor is a small nidus composed of osteoblasts and osteoid that creates a reactive area of dense cortical bone easily identified on plain films and CT scan (Figs. 10-17 and 10-18). They often occur around the proximal femur and acetabulum but can occur in any bone. They often arise in the posterior elements of the spine, where they are the most common cause of painful scoliosis (found on the concave side at the apex of the curve). The natural history is to gradually burn out, so long-term treatment with NSAIDs is an option, but most patients choose a radiofrequency ablation of the nidus with good results.

Figure 10-18. A computed tomography scan of the osteiod osteoma in Figure 10-17 shows the reactive bone formation around the nidus.

Osteoblastoma

Osteoblastomas (Fig. 10-19) are also known as giant osteiod osteomas. Pathologically, they are virtually identical. Osteoblastomas are more aggressive than osteoid osteomas and cause a geographic pattern of destruction with expansile remodeling. Stage 3 lesions can mimic malignant disease. They can be found in any bone (like osteoid osteomas, they too are seen in the posterior elements of the spine). The workup should include plain films, an MRI of the area, and possibly a biopsy in the aggressive lesions to rule out malignancy. Treatment is curettage of the lesion and reconstruction of the defect, often with bone graft.

Osteoblastomas (Fig. 10-19) are also known as giant osteiod osteomas. Pathologically, they are virtually identical. Osteoblastomas are more aggressive than osteoid osteomas and cause a geographic pattern of destruction with expansile remodeling. Stage 3 lesions can mimic malignant disease. They can be found in any bone (like osteoid osteomas, they too are seen in the posterior elements of the spine). The workup should include plain films, an MRI of the area, and possibly a biopsy in the aggressive lesions to rule out malignancy. Treatment is curettage of the lesion and reconstruction of the defect, often with bone graft.

Benign cartilage-forming tumors

Enchondromas are extremely common benign areas of mature hyaline cartilage that occur in the metaphyseal and diaphyseal areas of virtually any bone (Fig. 10-20). It is theorized that they arise from persistent rests of cartilage from the physis. They are usually incidental and can be treated with serial radiographs to follow for the rare instance of malignant degeneration. Sometimes, they can occupy large portions of the intramedullary canal and raise the possibility of a low-grade chondrosarcoma. The most reliable indicator of malignancy is pain at the site of the lesion, but this can be clinically difficult to distinguish from other musculoskeletal conditions. In cases of possibly painful enchondromas, it is advisable to refer the patient to a musculoskeletal oncologist for treatment. Enchondromas in the hand are often more aggressive clinically (although it is extremely uncommon for malignant degeneration) and can be treated with curettage and bone graft.

Enchondromas are extremely common benign areas of mature hyaline cartilage that occur in the metaphyseal and diaphyseal areas of virtually any bone (Fig. 10-20). It is theorized that they arise from persistent rests of cartilage from the physis. They are usually incidental and can be treated with serial radiographs to follow for the rare instance of malignant degeneration. Sometimes, they can occupy large portions of the intramedullary canal and raise the possibility of a low-grade chondrosarcoma. The most reliable indicator of malignancy is pain at the site of the lesion, but this can be clinically difficult to distinguish from other musculoskeletal conditions. In cases of possibly painful enchondromas, it is advisable to refer the patient to a musculoskeletal oncologist for treatment. Enchondromas in the hand are often more aggressive clinically (although it is extremely uncommon for malignant degeneration) and can be treated with curettage and bone graft.

Figure 10-20. The enchondroma in the proximal tibia shows the classic, stippled, or “rings and arcs” calcification.

Ollier disease, also known as enchondromatosis, is an autosomal dominant condition characterized by multiple enchondromas throughout the skeleton (Fig. 10-21). The patients often have growth disturbances and are of short stature. Because of the sheer number of lesions, there is a significant chance one of them will become malignant over the course of the patient’s lifetime.

Ollier disease, also known as enchondromatosis, is an autosomal dominant condition characterized by multiple enchondromas throughout the skeleton (Fig. 10-21). The patients often have growth disturbances and are of short stature. Because of the sheer number of lesions, there is a significant chance one of them will become malignant over the course of the patient’s lifetime.

Osteochondroma

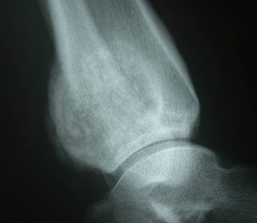

Osteochondromas, otherwise known as exostoses, are common benign bone tumors that present as exophytic boney masses (Fig. 10-22). They are thought to be aberrations of the growth plate and can be pedunculated (with a well-defined stalk) or sessile (having a more broad-based attachment to the underlying bone). All osteochondromas have corticomedullary continuity; that is, the medullary canal of the bone flows into the osteochondroma without interruption. The surface of osteochondromas is made up of a cartilage cap that is subject to the same growth regulation as any physis. Therefore, osteochondromas will grow until skeletal maturity, and then the cap tends to become thin and growth ceases. There is a small chance that the cartilage cap can degenerate into a (usually low-grade) chondrosarcoma. Treatment is excision for symptomatic lesions.

Osteochondromas, otherwise known as exostoses, are common benign bone tumors that present as exophytic boney masses (Fig. 10-22). They are thought to be aberrations of the growth plate and can be pedunculated (with a well-defined stalk) or sessile (having a more broad-based attachment to the underlying bone). All osteochondromas have corticomedullary continuity; that is, the medullary canal of the bone flows into the osteochondroma without interruption. The surface of osteochondromas is made up of a cartilage cap that is subject to the same growth regulation as any physis. Therefore, osteochondromas will grow until skeletal maturity, and then the cap tends to become thin and growth ceases. There is a small chance that the cartilage cap can degenerate into a (usually low-grade) chondrosarcoma. Treatment is excision for symptomatic lesions.

Figure 10-22. A large pedunculated osteochondroma of the distal femur.

Multiple hereditary exostosis (MHE), also known as osteochondromatosis, is an autosomal dominant disorder with many exostoses. Patients have growth disturbances (especially around the elbows, forearms, and ankles) and are of short stature. Like with Ollier disease, the chance of malignant transformation is much higher due to the numerous lesions.

Multiple hereditary exostosis (MHE), also known as osteochondromatosis, is an autosomal dominant disorder with many exostoses. Patients have growth disturbances (especially around the elbows, forearms, and ankles) and are of short stature. Like with Ollier disease, the chance of malignant transformation is much higher due to the numerous lesions.

Periosteal chondroma

A periosteal chondroma is a benign cartilaginous tumor on the surface of a bone that is often painful. On plain radiography it appears as a “scalloped-out” lesion on the surface of cortical bone with a thin rim of reactive bone around the actual cartilaginous tissue (Fig. 10-23). Microscopically it is benign lobules of cartilage. Treatment is curettage of the lesion and bone grafting of the defect if necessary.

A periosteal chondroma is a benign cartilaginous tumor on the surface of a bone that is often painful. On plain radiography it appears as a “scalloped-out” lesion on the surface of cortical bone with a thin rim of reactive bone around the actual cartilaginous tissue (Fig. 10-23). Microscopically it is benign lobules of cartilage. Treatment is curettage of the lesion and bone grafting of the defect if necessary.

Chondroblastoma

Chondroblastoma is a rare, benign proliferation of chondroblasts seen almost exclusively as a well-defined lytic lesion (occasionally with stippled calcifications) in the epiphyseal region of bone (Fig. 10-24). Benign fetal chondroblasts with characteristic “chicken wire” calcification are seen under the microscope. It is most commonly seen in patients between the ages of 15 and 25. In patients with open physes the other entity to consider is a Brodie”s abscess. Treatment is curettage and bone grafting. Occasionally chondroblastoma can metastasize to the lungs in a “benign fashion.” These lesions are usually treated successfully with wedge resection.

Chondroblastoma is a rare, benign proliferation of chondroblasts seen almost exclusively as a well-defined lytic lesion (occasionally with stippled calcifications) in the epiphyseal region of bone (Fig. 10-24). Benign fetal chondroblasts with characteristic “chicken wire” calcification are seen under the microscope. It is most commonly seen in patients between the ages of 15 and 25. In patients with open physes the other entity to consider is a Brodie”s abscess. Treatment is curettage and bone grafting. Occasionally chondroblastoma can metastasize to the lungs in a “benign fashion.” These lesions are usually treated successfully with wedge resection.

Chondromyxoid fibroma

Chondromyxoid fibroma is a rare, benign cartilaginous tumor characteristically seen in the metaphysis of the proximal tibia (although it can be seen in any bone) as a multiloculated lesion with a sclerotic rim that resembles a “soap bubble” (Fig. 10-25). These fibromas have a trimodal appearance under the microscope (hence the name) with characteristic spindle cells that have cytoplasmic projections resembling boat propellers. They can be locally aggressive and should be treated with curettage and bone grafting.

Giant cell tumor of bone

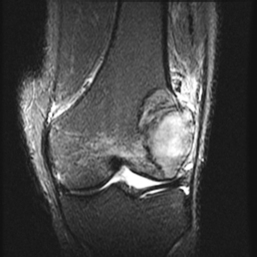

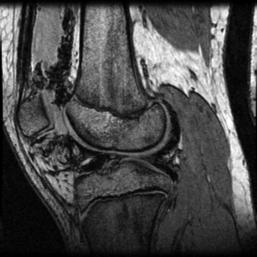

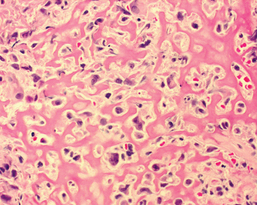

Giant cell tumor of bone is a benign bone tumor that arises in the metaphyseal-epiphyseal region of bone (and almost always extends to the subchondral region) in patients in their third through fifth decades of life. It is a lytic lesion usually without any sclerotic rim that can be aggressive and is often associated with a soft tissue mass (Figs. 10-26 and 10-27). Microscopically, there are large osteoclast-like giants cells with many nuclei in a stroma of mononuclear cells (Fig. 10-28). Like with chondroblastoma, “benign metastases” to the lung can occur and a chest radiograph to evaluate these patients is advisable (especially with lesions of the distal radius, which tend to be more aggressive).

Giant cell tumor of bone is a benign bone tumor that arises in the metaphyseal-epiphyseal region of bone (and almost always extends to the subchondral region) in patients in their third through fifth decades of life. It is a lytic lesion usually without any sclerotic rim that can be aggressive and is often associated with a soft tissue mass (Figs. 10-26 and 10-27). Microscopically, there are large osteoclast-like giants cells with many nuclei in a stroma of mononuclear cells (Fig. 10-28). Like with chondroblastoma, “benign metastases” to the lung can occur and a chest radiograph to evaluate these patients is advisable (especially with lesions of the distal radius, which tend to be more aggressive).

Figure 10-26. A giant cell tumor of the distal femur. Note the involvement of the epiphysis and metaphysis.

Figure 10-28. A high-power micrograph of a giant cell tumor demonstrating the large, multinucleated giant cells.

Because of their epiphyseal location, giant cell tumors can be challenging to treat. Curettage, high-speed burring, and some adjuvants (e.g., argon beam, cryotherapy, phenol) can reduce the rate of local recurrence and the defect can be filled with cement and/or bone graft. However, some aggressive disease requires wide excision and more complex reconstructions like joint replacement or fusion depending on the location and extent of disease.

Because of their epiphyseal location, giant cell tumors can be challenging to treat. Curettage, high-speed burring, and some adjuvants (e.g., argon beam, cryotherapy, phenol) can reduce the rate of local recurrence and the defect can be filled with cement and/or bone graft. However, some aggressive disease requires wide excision and more complex reconstructions like joint replacement or fusion depending on the location and extent of disease.

Fibrous lesions

Nonossifing fibroma, or NOF, is a benign, eccentric, metaphyseal lesion often seen as an incidental finding on radiographs done for another reason. The lesion presents as a well-defined area of radiolucency with a sclerotic border found on the endosteal surface of bone in children and teenagers (Fig. 10-29). The natural history is to fill in with bone over time, and NOFs can usually be treated expectantly. However, some lesions are large and can cause pain and even pathologic fracture. In these instances, curettage, bone grafting, and fixation is often necessary.

Nonossifing fibroma, or NOF, is a benign, eccentric, metaphyseal lesion often seen as an incidental finding on radiographs done for another reason. The lesion presents as a well-defined area of radiolucency with a sclerotic border found on the endosteal surface of bone in children and teenagers (Fig. 10-29). The natural history is to fill in with bone over time, and NOFs can usually be treated expectantly. However, some lesions are large and can cause pain and even pathologic fracture. In these instances, curettage, bone grafting, and fixation is often necessary.

Fibrous dysplasia

Fibrous dysplasia is a benign fibro-osseous proliferation during skeletal maturation that can occur in any bone but is most commonly seen in the femur and tibia. 80% of cases are isolated to a single bone (monostotic). Severe polyostotic cases are often associated with pigmented skin lesion and endocrine abnormalities (often precocious puberty), a syndrome called McCune Albright disease.

Fibrous dysplasia is a benign fibro-osseous proliferation during skeletal maturation that can occur in any bone but is most commonly seen in the femur and tibia. 80% of cases are isolated to a single bone (monostotic). Severe polyostotic cases are often associated with pigmented skin lesion and endocrine abnormalities (often precocious puberty), a syndrome called McCune Albright disease.

Radiographically, fibrous dysplasia displays symmetric cortical thinning and expansile remodeling down the long axis of the bone leading to the “long lesion in a long bone” description of the disease (Fig. 10-30). The matrix of the tumor on radiographs is classically described as “ground glass” and represents the microscopic areas of dysplastic bone (in an “alphabet soup” or “Chinese letters” configuration) in a benign fibrous stroma.

Radiographically, fibrous dysplasia displays symmetric cortical thinning and expansile remodeling down the long axis of the bone leading to the “long lesion in a long bone” description of the disease (Fig. 10-30). The matrix of the tumor on radiographs is classically described as “ground glass” and represents the microscopic areas of dysplastic bone (in an “alphabet soup” or “Chinese letters” configuration) in a benign fibrous stroma.

Figure 10-30. The “ground glass” appearance of fibrous dysplasia. Note the involvement of the entire bone.

Fibrous dysplasia can weaken the bone, cause pain, and lead to fractures. Multiple fractures of the proximal femur over time lead to deformity and the classic “shepherd’s crook” appearance. Asymptomatic lesions can be observed. Symptomatic lesions can be curetted and bone grafted. Unfortunately, the disease often returns and destroys the bone graft, so instrumentation or bulk allograft is usually employed.

Fibrous dysplasia can weaken the bone, cause pain, and lead to fractures. Multiple fractures of the proximal femur over time lead to deformity and the classic “shepherd’s crook” appearance. Asymptomatic lesions can be observed. Symptomatic lesions can be curetted and bone grafted. Unfortunately, the disease often returns and destroys the bone graft, so instrumentation or bulk allograft is usually employed.

Adamantinoma

Adamantinoma is an exceedingly rare low-grade malignant fibrous tumor that almost always arises in the anterior cortex of the tibia in younger patients with closed growth plates. Radiographically, it is a bubbly, multiloculated lesion with sclerotic borders (Fig. 10-31). It has several different pathologic patterns, but cytokeratin is always expressed. It is a malignancy, so the patients have to be worked up for metastatic disease. Treatment is wide surgical excision only. A bulk allograft is often used for reconstruction.

Adamantinoma is an exceedingly rare low-grade malignant fibrous tumor that almost always arises in the anterior cortex of the tibia in younger patients with closed growth plates. Radiographically, it is a bubbly, multiloculated lesion with sclerotic borders (Fig. 10-31). It has several different pathologic patterns, but cytokeratin is always expressed. It is a malignancy, so the patients have to be worked up for metastatic disease. Treatment is wide surgical excision only. A bulk allograft is often used for reconstruction.

Osteofibrous dysplasia

Osteofibrous dysplasia, also known as OFD or Campanacci disease, is a benign condition with a similar appearance to adamantinoma seen in the anterior cortex of the tibia in patients with open physes. Some experts believe it could represent a precursor lesion to adamantinoma. It resembles fibrous dyplasia under the microscope, except the areas of dysplastic bone are rimmed by osteoblasts. Most cases are self-limited and stop growing at skeletal maturity, so watchful waiting is the treatment of choice.

Osteofibrous dysplasia, also known as OFD or Campanacci disease, is a benign condition with a similar appearance to adamantinoma seen in the anterior cortex of the tibia in patients with open physes. Some experts believe it could represent a precursor lesion to adamantinoma. It resembles fibrous dyplasia under the microscope, except the areas of dysplastic bone are rimmed by osteoblasts. Most cases are self-limited and stop growing at skeletal maturity, so watchful waiting is the treatment of choice.

Bone cysts

Bone cysts are benign, fluid-filled cavities that appear as radiolucent lesions on radiograph. MRI confirms the fluid nature and rules out a solid tumor.

Bone cysts are benign, fluid-filled cavities that appear as radiolucent lesions on radiograph. MRI confirms the fluid nature and rules out a solid tumor.

Simple bone cyst

A simple or unicameral bone cyst is a single-chambered, symmetric, and central lytic lesion seen in children and adolescents most commonly in the metaphysis of the proximal humerus just below the growth plate (although lesions in the proximal femur and about the knee occur). The lesion thins and expands the cortical bone, presenting with pain or a pathologic fracture (Fig. 10-32). A thin wafer of cortical bone that fractures and floats to the bottom of the cyst is called a “fallen leaf” sign. In the proximal humerus, these fractures will heal with the cyst often recurring. Multiple fractures can lead to deformity. Treatment of proximal humerus lesions should begin with allowing fractures to heal followed by aspiration and injection of bone graft into the cyst. Sometimes, when the cyst has migrated away from the physis, intramedullary rods can be used to correct deformity or prevent further fractures. Because of the high stresses around the proximal femur, simple cysts in that area should be treated more aggressively with instrumentation.

A simple or unicameral bone cyst is a single-chambered, symmetric, and central lytic lesion seen in children and adolescents most commonly in the metaphysis of the proximal humerus just below the growth plate (although lesions in the proximal femur and about the knee occur). The lesion thins and expands the cortical bone, presenting with pain or a pathologic fracture (Fig. 10-32). A thin wafer of cortical bone that fractures and floats to the bottom of the cyst is called a “fallen leaf” sign. In the proximal humerus, these fractures will heal with the cyst often recurring. Multiple fractures can lead to deformity. Treatment of proximal humerus lesions should begin with allowing fractures to heal followed by aspiration and injection of bone graft into the cyst. Sometimes, when the cyst has migrated away from the physis, intramedullary rods can be used to correct deformity or prevent further fractures. Because of the high stresses around the proximal femur, simple cysts in that area should be treated more aggressively with instrumentation.

Aneurysmal bone cyst

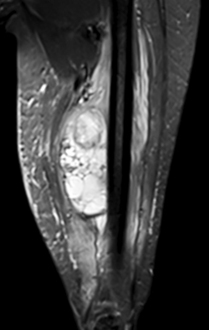

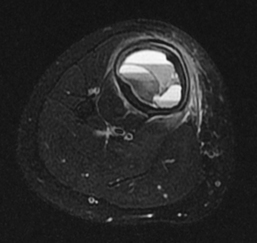

An aneurysmal bone cyst, or ABC, is a benign, eccentric, expansile, lytic lesion made up of multiple cavities filled with blood (Fig. 10-33). On MRI, the blood settles out and characteristic fluid-fluid levels are seen on T2-weighted images (Fig. 10-34). They most commonly occur around the knee but can also be seen in the posterior elements of the spine. ABCs can be locally aggressive and mimic a telangiectatic osteosarcoma. Pathology should be carefully examined to rule out malignancy and a precursor lesion (such as chondroblastoma or chondromyxoid fibroma). Standard treatment is curettage and bone graft, but large lesions may need to be embolized as well.

An aneurysmal bone cyst, or ABC, is a benign, eccentric, expansile, lytic lesion made up of multiple cavities filled with blood (Fig. 10-33). On MRI, the blood settles out and characteristic fluid-fluid levels are seen on T2-weighted images (Fig. 10-34). They most commonly occur around the knee but can also be seen in the posterior elements of the spine. ABCs can be locally aggressive and mimic a telangiectatic osteosarcoma. Pathology should be carefully examined to rule out malignancy and a precursor lesion (such as chondroblastoma or chondromyxoid fibroma). Standard treatment is curettage and bone graft, but large lesions may need to be embolized as well.

Figure 10-34. An axial magnetic resonance image of the cyst in Figure 10-33 shows the multiple septations and fluid-fluid levels.

Epidermal inclusion cyst

An epidermal inclusion cyst can be seen in bone as a lytic lesion in the distal phalanges of the fingers and toes. There is normally a history of trauma, and theoretically epidermal tissue is introduced into the periosteum, where it proliferates into a cyst. These may present with pain or a fracture and can require curettage and bone grafting.

An epidermal inclusion cyst can be seen in bone as a lytic lesion in the distal phalanges of the fingers and toes. There is normally a history of trauma, and theoretically epidermal tissue is introduced into the periosteum, where it proliferates into a cyst. These may present with pain or a fracture and can require curettage and bone grafting.

Intra-articular tumors

Synovial chondromatosis is an intra-articular metaplastic disease in which the synovial tissue forms multiple nodules of otherwise normal hyaline cartilage. These can be seen as a sea of calcified masses around a joint, with the knee being the most commonly affected (Fig. 10-35). The many loose bodies can damage the normal cartilage, so removal and synovectomy are the treatments of choice.

Synovial chondromatosis is an intra-articular metaplastic disease in which the synovial tissue forms multiple nodules of otherwise normal hyaline cartilage. These can be seen as a sea of calcified masses around a joint, with the knee being the most commonly affected (Fig. 10-35). The many loose bodies can damage the normal cartilage, so removal and synovectomy are the treatments of choice.

Figure 10-35. Synovial chondromatosis of the tibiotalar joint.

Pigmented villonodular synovitis

Pigmented villonodular synovitis, or PVNS, is a benign, proliferative disease of the synovium. It can affect almost any joint, but it is most common in the knee of patients in their third or fourth decade of life. On MRI, due to the hemosiderin deposition in the tissue, the lesions have a characteristic low intensity on both T1- and T2-weighted images (Fig. 10-36). It can present as a focal, nodular mass or as a more diffuse, villous involvement of the entire joint. The nodular form is easily treated with excision, but the diffuse form can damage the joint and be challenging to treat (recurrence is common even after attempted total synovectomy).

Pigmented villonodular synovitis, or PVNS, is a benign, proliferative disease of the synovium. It can affect almost any joint, but it is most common in the knee of patients in their third or fourth decade of life. On MRI, due to the hemosiderin deposition in the tissue, the lesions have a characteristic low intensity on both T1- and T2-weighted images (Fig. 10-36). It can present as a focal, nodular mass or as a more diffuse, villous involvement of the entire joint. The nodular form is easily treated with excision, but the diffuse form can damage the joint and be challenging to treat (recurrence is common even after attempted total synovectomy).

Eosinophilic granuloma

Eosinophilic grauloma (EG) is a benign, lytic bone lesion seen in children and adolescents, most commonly in flat bones and the diaphysis of long bones. It is often called the great imitator because of its varied appearance radiographically, but classically it is a well-defined “hole in bone” (Fig. 10-37). Histologically, eosinophils are usually seen along with larger histiocytic cells called Langerhans cells. EG can manifest as a systemic disease (Langerhans cell granulomatosis) and be seen in multiple bones and other organs. Treatment for bone disease can simply be steroid injection. Larger or unstable lesions may need curettage and fixation.

Eosinophilic grauloma (EG) is a benign, lytic bone lesion seen in children and adolescents, most commonly in flat bones and the diaphysis of long bones. It is often called the great imitator because of its varied appearance radiographically, but classically it is a well-defined “hole in bone” (Fig. 10-37). Histologically, eosinophils are usually seen along with larger histiocytic cells called Langerhans cells. EG can manifest as a systemic disease (Langerhans cell granulomatosis) and be seen in multiple bones and other organs. Treatment for bone disease can simply be steroid injection. Larger or unstable lesions may need curettage and fixation.

Soft tissue lesions

The orthopaedic oncologist also treats soft tissue masses of the extremities and joints. There are many different benign and malignant soft tissue masses that may present in children and adults. These should be worked up with an MRI to gain as much knowledge about the actual tissue in addition to the anatomic location.

The orthopaedic oncologist also treats soft tissue masses of the extremities and joints. There are many different benign and malignant soft tissue masses that may present in children and adults. These should be worked up with an MRI to gain as much knowledge about the actual tissue in addition to the anatomic location.

Classically, a soft tissue sarcoma presents as an enlarging, painless mass in an older patient. The classic MRI findings of a soft tissue sarcoma (no matter what the histologic subtype) are intermediate intensity on T1-weighted images and bright and heterogeneous on T2-weighted images (Fig. 10-38). After being staged for metastatic disease with CT scans, these masses should be biopsied by or under the direction of the treating surgeon. Standard treatment is surgery and radiation therapy (it may be preoperative or postoperative depending on the tumor and surgeon preference). Chemotherapy is being studied as adjuvant treatment for soft tissue sarcomas and can be useful in some subtypes. Local recurrence rates for soft tissue sarcomas are low, but 5-year survival rates are poor, especially in patients with metastatic disease.

Classically, a soft tissue sarcoma presents as an enlarging, painless mass in an older patient. The classic MRI findings of a soft tissue sarcoma (no matter what the histologic subtype) are intermediate intensity on T1-weighted images and bright and heterogeneous on T2-weighted images (Fig. 10-38). After being staged for metastatic disease with CT scans, these masses should be biopsied by or under the direction of the treating surgeon. Standard treatment is surgery and radiation therapy (it may be preoperative or postoperative depending on the tumor and surgeon preference). Chemotherapy is being studied as adjuvant treatment for soft tissue sarcomas and can be useful in some subtypes. Local recurrence rates for soft tissue sarcomas are low, but 5-year survival rates are poor, especially in patients with metastatic disease.

Soft tissue masses in the extremities are most commonly benign, and there are many possible diagnoses. Lipomas, or benign fatty tumors, are exceedingly common and can be diagnosed from MRI alone before surgical resection. However, many benign soft tissue masses can have indeterminate MRI findings or even mimic a sarcoma. These masses should be referred to a treating surgeon for further treatment.

Soft tissue masses in the extremities are most commonly benign, and there are many possible diagnoses. Lipomas, or benign fatty tumors, are exceedingly common and can be diagnosed from MRI alone before surgical resection. However, many benign soft tissue masses can have indeterminate MRI findings or even mimic a sarcoma. These masses should be referred to a treating surgeon for further treatment.