Chapter 50 Organizing Pneumonia

Definition

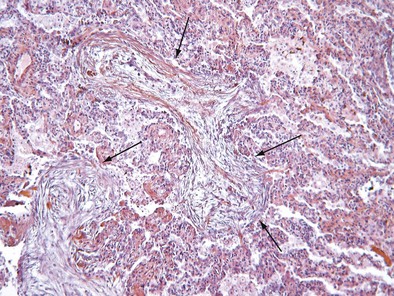

Initially described as the specific histopathologic pattern resulting from organization of an inflammatory exudate in the lumen of alveoli of unresolved pneumonia, OP is characterized by intraalveolar buds of granulation tissue with fibroblasts and myofibroblasts intermixed with loose connective matrix (Figure 50-1). Similar lesions may be present within the lumen of the bronchioles—hence the formerly synonymous term bronchiolitis obliterans with organizing pneumonia (“BOOP”). The latter designation has been abandoned, however, because OP (rather than bronchiolitis) is clearly the major lesion, and furthermore, use of the older term was a potential source of confusion between this entity and bronchiolitis with airflow obstruction occurring, for example, after lung or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Although the condition is not strictly interstitial, COP is included in the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society international consensus classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias, because of its idiopathic nature and occasional similarities with interstitial pneumonias.

Pathogenesis

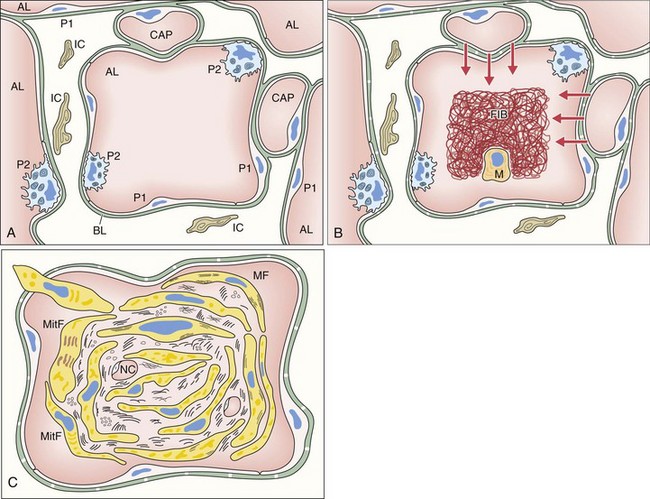

The first event of the sequence leading to the formation of intraalveolar buds is alveolar epithelial injury with necrosis of pneumocytes (especially type I) (Figure 50-2). The epithelial basal laminae are denuded and injured, resulting in formation of gaps. Capillary endothelial injury often is associated. The consequence of alveolar injury is flooding of the alveolar lumen by plasma proteins (permeability edema), including coagulation factors. The balance between coagulation and fibrinolysis is clearly tipped in favor of coagulation (especially because of decreased fibrinolysis), leading to accumulation of fibrin deposits that are soon populated by migratory inflammatory cells and fibroblasts.

Clinical and Imaging Features

Cryptogenic Organizing Pneumonia

Imaging Features

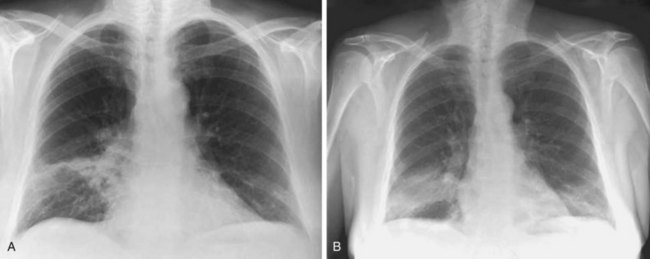

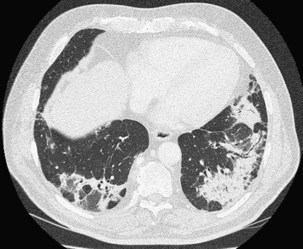

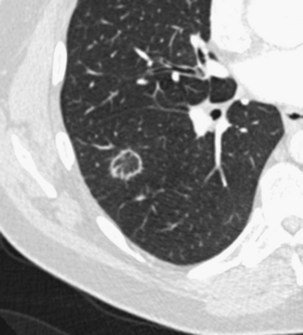

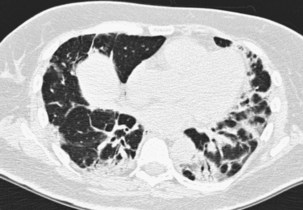

The imaging features of COP may consist of a variety of high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) findings, some of which are highly suggestive of the diagnosis. The most typical imaging pattern in COP consists of multiple patchy alveolar opacities (Figures 50-3 and 50-4). These usually are bilateral, with a subpleural distribution, and sometimes migratory (with attenuation or clearing in some areas and appearance of new opacities in others), ranging in density from ground glass to consolidation with air bronchogram, with no predominance in cranial versus caudal distribution. The size of the opacities may vary, ranging from 1 to 2 cm to involvement of an entire lobe. Consolidation at imaging corresponds pathologically with intraalveolar buds of granulation tissue within the distal air spaces, whereas areas of ground glass opacity reflect the cell infiltration of alveolar wall by inflammatory cells, with some OP changes in the distal air spaces. This imaging pattern with multiple patchy alveolar opacities, especially those of a migratory nature, is so characteristic of typical COP that it should immediately suggest the diagnosis. The main other consideration in the differential diagnosis at this stage is idiopathic chronic eosinophilic pneumonia (in the latter, blood eosinophilia with cell counts usually greater than 1500/µL is present; conversely, nodules may be found more frequently in COP than in chronic eosinophilic pneumonia).

Patchy ground glass opacities frequently are observed, usually associated with consolidation. The reverse halo sign or atoll sign (Figure 50-5), consisting of a circular consolidation pattern (corresponding histopathologically to organizing pneumonia in the distal air spaces) surrounding an area of ground glass opacities (corresponding to alveolar wall inflammation), also is highly suggestive of the diagnosis, although not specific.

The infiltrative (or progressive fibrotic) pattern of OP associates interstitial opacities, with small superimposed alveolar opacities on HRCT (with possible perilobular pattern consisting of bowed or polygonal opacities with poorly defined margins bordering the interlobular septa). Honeycombing is not present. Infiltrative or progressive COP may overlap on both histopathologic and imaging studies with idiopathic nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP), with uniform alveolar and interstitial cellular inflammation (with more or less fibrosis), with the possible presence of foci of organizing pneumonia. Such imaging presentation of OP seems to be particularly frequent in patients with idiopathic inflammatory myopathy (Figure 50-6).

Several less common imaging presentations of COP have been occasionally reported, including multiple nodules, cavitary opacities, perilobular opacities, centrilobular or peribronchovascular ill-defined nodules, bronchocentric areas of consolidation, and linear subpleural bands (Box 50-1). A few mediastinal lymphadenopathies are not rare in COP. Pleural effusion is uncommon.

Box 50-1

High-Resolution Computed Tomography Patterns in Organizing Pneumonia

COP, cryptogenic organizing pneumonia.

Modified from King TE: Organizing pneumonia. In Schwarz MI, King TE, editors: Interstitial lung disease, ed 5, Shelton, Conn, People’s Medical Publishing House, 2011, pp 981–984.

Whereas mimics of COP with typical imaging features are few, mimics of COP presenting as nodules, masses, or infiltrative lung diseases are many (Box 50-2).

Box 50-2

Mimics of Cryptogenic Organizing Pneumonia (COP) on Chest Imaging

Multiple patchy alveolar opacities (classic COP pattern)

Solitary focal nodule or mass (focal pattern)

Diffuse infiltrative opacities (progressive or fibrosis pattern)

Secondary Organizing Pneumonia

Secondary Organizing Pneumonia of Known Cause

A histopathologic diagnosis of OP prompts a search for a number of potential underlying causes, including a variety of infectious agents (bacteria, viruses, fungi, parasites) (Box 50-3). Diagnosis of the infection (which is no longer active at the time of OP) may be difficult and is based on the clinical history, a rise in antibody titers against the infectious agent, or occasionally direct identification of the infectious agent by use of specific stains and histopathologic analysis of the lung specimens.

Several drugs have been reported to cause OP (Box 50-4). All drugs taken in the weeks or months preceding onset of symptoms must be systematically recorded. Any drug suspected to be a cause of OP should be withdrawn if possible (and rechallenge should be avoided). The diagnosis of drug-induced OP may be difficult, however, because it has no specific clinical-radiologic presentation.

Secondary Organizing Pneumonia Occurring Within a Specific Context

Multiple causes of and clinical settings for secondary OP have been reported, a nonexhaustive listing of which is provided in Box 50-5.

Box 50-5

Miscellaneous Causes and Clinical Settings Associated With Organizing Pneumonia

Clinical Settings

Inflammatory bowel diseases (ulcerative colitis, Crohn disease)

Transplantation (lung, liver), bone marrow graft

Hematologic malignancies (leukemias: myeloblastic, lymphoblastic, myelomonocytic, T cell; Hodgkin disease)

Cancers and thoracic radiotherapy, especially for breast cancer

Others: common variable immune deficiency, Sweet syndrome, polymyalgia rheumatica, Behçet disease, thyroid diseases, vasculitis, sarcoidosis

Diagnosis

A reasonable alternative to lung biopsy is to proceed with appropriate management, to include presumptive treatment as indicated, in the absence of confirmation of the histopathologic pattern of OP. Although this approach commonly is used in clinical practice, it carries the risk of misdiagnosing alternative conditions that may mimic OP, including eosinophilic pneumonia, low-grade primary pulmonary lymphoma, and bronchioloalveolar carcinoma (see Box 50-2). Only patients in whom typical findings on imaging studies (e.g., multiple patchy consolidation) are associated with compatible clinical and BAL features should be treated without biopsy; particular attention must be paid to any clue to an alternative diagnosis (e.g., peripheral blood and/or BAL fluid eosinophilia, suggestive microbiologic findings in BAL fluid). When pathologic investigation is not available or consists of only transbronchial biopsy, the diagnosis should be reconsidered whenever the observed clinical response is unusual (especially in case of incomplete response to corticosteroids or relapse despite more than 20 mg/day of oral prednisone).

As in other conditions among the group of idiopathic interstitial pneumonias, the “gold standard” for diagnosis of OP is now the clinical-radiologic-pathologic approach, which effectively ensures that imaging and clinical data, as well as pathology data when available, are consistent with and specific for this entity. Although interobserver agreement for a clinically based diagnosis usually is fair to good, the multidisciplinary approach is particularly useful in cases with histopathologic features overlapping with those of eosinophilic pneumonia, nonspecific interstitial pneumonia, or diffuse alveolar damage. The clinical assessment must include a careful history and evaluation for the presence of comorbid diseases such as connective tissue disease (including formes frustes of connective tissue disease or undifferentiated connective tissue disease), cancer, thoracic radiotherapy for breast cancer, exposure to drugs, inflammatory bowel disease, aspiration, or less common conditions such as common variable immune deficiency (see Box 50-5). A final diagnosis of COP can be made only after all available data including findings on etiologic investigations have been reviewed in a dynamic process requiring close communication among the clinician, the radiologist, and the pathologist.

Treatment of Cryptogenic Organizing Pneumonia

Corticosteroid treatment is standard therapy for COP and results in rapid clinical and imaging improvement in typical cases. With institution of therapy, consolidation evolves to ground glass opacities and reticulation and eventually regresses completely within a month; the less frequent linear or reticular opacities may not resolve. The optimal doses and duration of treatment have not been established, and treatment should aim at the best balance between disease control and side effects. We start with prednisone, 0.75 mg/kg per day for 4 weeks, and then continue with progressively decreasing doses for a total duration of treatment of 24 weeks (Table 50-1). This regimen limits intense and prolonged corticosteroid treatment with ensuing risk of iatrogenic complications. Other treatment protocols with slower tapering of dosage have been proposed. Parenteral corticosteroid therapy at higher doses often is used as the initial treatment in patients with the progressive or fibrotic variant of COP. Cyclophosphamide or azathioprine may be used in patients whose clinical condition deteriorates despite corticosteroid therapy. Of note, spontaneous improvement has been reported in some cases of COP. Macrolides have been suggested for their antiinflammatory properties as an alternative option in patients who are intolerant to corticosteroids or who experience frequent relapses; however, the benefit initially observed in case reports is not confirmed with empirical routine use of these drugs. Secondary OP requires treatment of the underlying condition (connective tissue disease, infection) or withdrawal of the causative drug or exposure. Focal COP does not require corticosteroid therapy after surgical resection (performed for suspected lung cancer).

Table 50-1 Proposed Therapeutic Regimen for Typical Cryptogenic Organizing Pneumonia

| Step | Duration | Prednisone Dosage |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment of Initial Episode | ||

| 1 | 4 weeks | 0.75 mg/kg/d |

| 2 | 4 weeks | 0.5 mg/kg/d |

| 3 | 4 weeks | 20 mg/d |

| 4 | 6 weeks | 10 mg/d |

| 5 | 6 weeks | 5 mg/d |

| Treatment of Relapse | ||

| 1 | 12 weeks | 20 mg/d |

| 2 | 6 weeks | 10 mg/d |

| 3 | 6 weeks | 5 mg/d |

Controversies and Pitfalls

• OP is defined as a nonspecific histopathologic pattern found in many disorders, especially nonresolving infectious pneumonia. Assessing its clinical significance may be difficult. OP may be difficult to distinguish histopathologically from focal areas of organizing-type pneumonia seen as an accessory finding in another disorder (e.g., nonspecific interstitial pneumonia, organizing diffuse alveolar damage).

• In complex cases, overlap with other recognized histologic patterns may occur, especially with nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (especially secondary OP).

• What differentiates the pathogenic fibrosing process of OP (which resolves with corticosteroids) from that of uncontrolled idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (resistant to steroids) is poorly understood.

• In cases with typical clinical, radiologic, and BAL findings, initiation of therapy without histopathologic confirmation may be considered; however, the diagnosis must be reconsidered whenever the outcome is unusual. The optimal dose and duration of corticosteroid therapy have not been established. Disease control must be balanced with treatment side effects.

• Whether AFOP represents a variant of OP or a distinct entity is unknown.

American Thoracic Society; European Respiratory Society. American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society International Multidisciplinary Consensus Classification of the Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:277–304.

Beasley MB, Franks TJ, Galvin JR, et al. Acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia: a histological pattern of lung injury and possible variant of diffuse alveolar damage. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2002;126:1064–1070.

Colby TV. Pathologic aspects of bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia. Chest. 1992;102:38S–43S.

Cordier JF. Cryptogenic organising pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2006;28:422–446.

Cordier JF, Loire R, Brune J. Idiopathic bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia. Definition of characteristic clinical profiles in a series of 16 patients. Chest. 1989;96:999–1004.

Costabel U, Teschler H, Guzman J. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia (BOOP): the cytological and immunocytological profile of bronchoalveolar lavage. Eur Respir J. 1992;5:791–797.

Crestani B, Valeyre D, Roden S, et al. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia syndrome primed by radiation therapy to the breast. The Groupe d’Etudes et de Recherche sur les Maladies “Orphelines” Pulmonaires (GERM“O”P). Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158:1929–1935.

Davison AG, Heard BE, McAllister WAC, Turner-Warwick ME. Cryptogenic organizing pneumonitis. Q J Med. 1983;52:382–394.

Drakopanagiotakis F, Paschalaki K, Abu-Hijleh M, et al. Cryptogenic and secondary organizing pneumonia. Chest. 2011;139:893–900.

Epler GR, Colby TV, McLoud TC, et al. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:152–158.

King TE. Organizing pneumonia. In: Schwarz MI, King TE. Interstitial lung disease. ed 5. Conn: People’s Medical Publishing House; 2011:981–984.

Lazor R, Vandevenne A, Pelletier A, et al. Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia. Characteristics of relapses in a series of 48 patients. The Groupe d’Etudes et de Recherche sur les Maladles “Orphelines” Pulmonaires (GERM“O”P). Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:571–577.

Lee JW, Lee KS, Lee HY, et al. Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia: serial high-resolution CT findings in 22 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;195:916–922.

Lohr RH, Boland BJ, Douglas WW, et al. Organizing pneumonia. Features and prognosis of cryptogenic, secondary, and focal variants. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:1323–1329.

Maldonado F, Daniels C, Hoffman EA, et al. Focal organizing pneumonia on surgical lung biopsy. Causes, clinicoradiologic features, and outcome. Chest. 2007;132:1579–1583.

Mukhopadhyay S, Katzenstein AL. Pulmonary disease due to aspiration of food and other particulate matter: a clinicopathologic study of 59 cases diagnosed on biopsy or resection specimen. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:752–759.

Peyrol S, Cordier JF, Grimaud JA. Intra-alveolar fibrosis of idiopathic bronchiolitis obliterans-organizing pneumonia. Cell-matrix patterns. Am J Pathol. 1990;137:155–170.

Vasu TS, Cavallazzi R, Ilirani A, et al. Clinical and radiologic distinction between secondary bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia and cryptogenic organizing pneumonia. Respir Care. 2009;54:1028–1032.