CHAPTER 1 ORGANIZATIONAL ISSUES

DEFINITIONS

Traditional definitions of ICUs and high dependency units (HDUs) attempt to separate the functions of each.

LEVELS OF CARE

Critically ill patients can be classified according to the level of medical and nursing care required (see Intensive Care Society 2002 Levels of Critical Care for Adult Patients www.ics.ac.uk/icmprof/downloads/icsstandards-levelsofca.pdf) (Table 1.1).

| Level 0 | Patients whose needs can be met by ward-based care in an acute hospital. |

| Level 1 | Patients at risk of their condition deteriorating (including those recently moved from higher levels of care) whose needs can be met on a normal ward with additional advice or support from the critical care team. |

| Level 2 | Patients requiring more advanced levels of observation or intervention than can be provided on a normal ward, including support for a single failing organ system. |

| Level 3 | Patients requiring advanced respiratory support alone or basic respiratory support together with support for at least two organ systems. |

Specialist care is recorded by attaching one of the following letters as a suffix.

N – neurosurgical, C – cardiac, T – thoracic, B – burns, S – spinal injury, R – renal, L – liver, A – other specialist care.

Patients should be nursed in an area capable of providing the appropriate level of care. While level 2 care may be provided in an HDU or ICU, true level 3 care can only be provided in a suitably equipped ICU. In reality, these levels of care are not discrete entities, but represent points on a continuum or spectrum. As their condition changes, patients may need a greater or lesser level of care, and frequently move between the defined levels.

IDENTIFICATION OF PATIENTS AT RISK

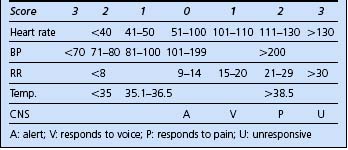

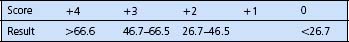

A number of scoring systems have been developed to help staff detect those patients who are at risk. These are based on the principle that patients develop abnormal physiological parameters as their condition starts to deteriorate. The scoring system can be used by any member of the ward medical or nursing staff and if appropriate, the intensive care outreach team can be called (see below). An example of a typical early warning scoring system is shown in Table 1.2. The response triggered by the scoring system is shown in Table 1.3.

| Ward area | Score > 3 | Call outreach team |

| High dependency area | Score > 3 Score > 5 |

Call responsible medical staff Call outreach team / ICU |

| Any area | Score > 10 | Call outreach Team / ICU |

CRITICAL CARE OUTREACH

Occasionally the outreach team may, in consultation with the patient, relatives, and the parent medical team, decide that a patient is unlikely to benefit from intensive care and that admission would not be appropriate (see Limitation of treatment, p. 430).

ADMISSION POLICIES

The aim of intensive care is to support patients while they recover. It is not to prolong life when there is no hope of recovery. Sometimes difficult decisions have to be made about whether or not to admit a patient to intensive care, as there is often a shortage of intensive care beds and a requirement to use the available resources responsibly and equitably. To aid decision making, some units have written admission policies. A typical admission policy is shown in Box 1.1.

Box 1.1 Admission policy

The difficulty with all admission policies, however, is that it is impossible to predict with complete accuracy which individual patients stand to benefit from admission to intensive care.

PREDICTION OF OUTCOME

There is, as yet, no satisfactory diagnostic categorization for intensive care patients. Often the problems relating to intensive care admission bear little relation to the original presenting complaint or diagnostic category.

There is, as yet, no satisfactory diagnostic categorization for intensive care patients. Often the problems relating to intensive care admission bear little relation to the original presenting complaint or diagnostic category. Although patients may survive to leave the ICU, there is a significant mortality on the wards, and later at home, after leaving intensive care. Many studies use 28-day mortality as an end point. It has been suggested that 6-month or 1-year outcomes of mortality and measures of morbidity (quality of life measures) are better end points.

Although patients may survive to leave the ICU, there is a significant mortality on the wards, and later at home, after leaving intensive care. Many studies use 28-day mortality as an end point. It has been suggested that 6-month or 1-year outcomes of mortality and measures of morbidity (quality of life measures) are better end points.APACHE II SEVERITY OF ILLNESS SCORE

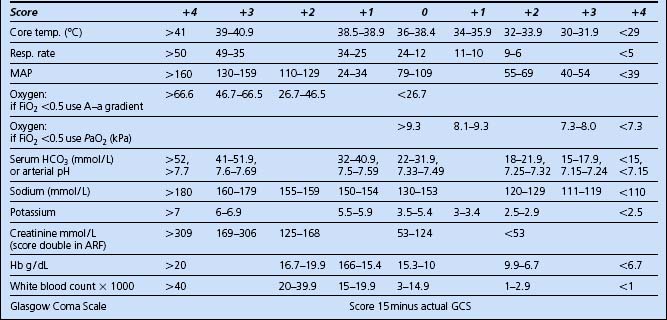

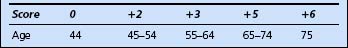

A score is assigned to each patient on the basis of:

Box 1.2 APACHE II

| For patients with severe organ system insuffi ciency or immune compromise, assign scores as shown. | |

| Condition must have been evident prior to this hospital admission and conform to the defi nitions below. | |

| Category | Score |

| For non-operative or emergency postoperative patients | +5 |

| For elective postoperative patients | +2 |

CVS New York Heart Association Class IV.

Notes on completing APACHE II scores

Where results are not available, score as zero. This does not mean that you do not have to try to find the result first!

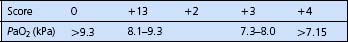

Where results are not available, score as zero. This does not mean that you do not have to try to find the result first!Oxygen

FiO2 > 0.5: Calculate the alveolar–arterial oxygen difference or (A–a)DO2 expressed in kPa:

The result of this gives the Aa gradient, which is then scored from the APACHE table:

Problems with APACHE II

There are a number of problems with the APACHE II score:

Patients with an APACHE II score >35 are unlikely to survive. However, the score is a statistical tool based on the population, and scores for individuals cannot be used to predict outcome. Some patients, for example those with diabetic ketoacidosis, may have marked physiological abnormalities, but generally get better quickly.

Patients with an APACHE II score >35 are unlikely to survive. However, the score is a statistical tool based on the population, and scores for individuals cannot be used to predict outcome. Some patients, for example those with diabetic ketoacidosis, may have marked physiological abnormalities, but generally get better quickly. The score is based on historical data, and as new interventions are developed, the data become obsolete.

The score is based on historical data, and as new interventions are developed, the data become obsolete. Lead-time bias results from the stabilization of patients in the referring hospital prior to transfer. This artificially lowers the score for the patient arriving at the referral centre.

Lead-time bias results from the stabilization of patients in the referring hospital prior to transfer. This artificially lowers the score for the patient arriving at the referral centre.ALTERNATIVE SEVERITY OF ILLNESS SCORING SYSTEMS

TISS

The Therapeutic Intervention Score System assigns a value to each procedure performed in the ICU. The implication is that the more procedures that are performed on a patient, the sicker they are. It is dependent on the doctor and unit, however, since different hospitals will have varying thresholds for carrying out many procedures. The score is therefore not good for comparing outcome between patients or between different units, but is useful as a general guide to the type of care and resources likely to be needed by patients on an individual unit.

DISCHARGE POLICIES

Either: the patient’s condition has improved to the extent that intensive care is no longer required.

Either: the patient’s condition has improved to the extent that intensive care is no longer required. Or: the patient’s condition is not improving and the underlying problems are such that continued intensive care is considered futile by staff on the ICU.

Or: the patient’s condition is not improving and the underlying problems are such that continued intensive care is considered futile by staff on the ICU.1. When are patients fit to be discharged?

In simple terms, patients are fit for discharge from intensive care when they no longer require the specialist skills and monitoring available on the ICU. This generally means that they have no life-threatening organ failure and that their underlying disease process is stable or improving. Table 1.6 gives some guidance.

| Airway | Adequate airway and cough to clear secretions (if inadequate, tracheostomy and suction, see below) |

| Breathing | Adequate respiratory effort and blood gases May be on oxygen (e.g. from face mask) Not requiring CPAP or non-invasive ventilation (unless discharged to HDU or respiratory unit), see below |

| Circulation | Stable, no inotropes |

| Neurological function | Adequate conscious level Adequate cough and gag refl exes (if inadequate, e.g. bulbar palsy or brain injury may need tracheostomy to make airway safe and allow suction) |

| Renal function | Renal function stable or improving Not requiring renal support unless discharged to a unit which performs dialysis |

| Analgesia | Adequate pain control |

2. Where is the patient to be sent?

This will depend at least in part on the patient’s underlying diagnosis, current condition, and where the patient came from in the first place. Some patients, especially elective postoperative surgical patients, may be fit enough to go straight back to a general ward. Others may, because of continuing organ dysfunction or other problems, require closer monitoring, supervision and nursing care and may go back to an HDU. Increasingly patients with chronic respiratory disease or those who are slow to wean from a ventilator may be transferred to a respiratory HDU capable of providing CPAP and non-invasive forms of ventilation. Some centres are developing specific long-term weaning units for this purpose and for caring for patients with tracheostomies.

Occasionally, patients may either self-discharge or be fit for discharge home prior to a ward bed becoming available (e.g. after overdosage of sedative drugs). In such cases the patient’s family or friends may be able to attend to take them home direct from ICU.