27 Organ Donation and Transplantation

Introduction

Transplantation is a life-saving and cost-effective form of treatment that enhances the quality of life for many people with end-stage chronic diseases. Transplantation surgery commenced in Australia in 1911, with a pancreas transplant in Launceston General Hospital, Tasmania. Other tissue and solid organ transplantations followed, retrieved from donors without cardiac function; the first cornea in 1941; kidney in 1956; and livers and hearts in 1968. Transplantation in New Zealand began in the 1940s with corneal grafting, and the first organ transplants were kidney and heart valve transplantation in the 1960s.1

The first successful human-to-human transplant of any kind was a corneal transplant performed in Moravia (now the Czech Republic) in 1905.1 In September of 1968 an ad hoc committee of Harvard Medical School produced a report on the ‘hopelessly unconscious patient.’ The committee members agreed that life support could be withdrawn from patients diagnosed with ‘irreversible coma’ or ‘brain death’ (terms they used interchangeably) and that, with appropriate consent, the organs could be removed for transplantation.13 The committee’s primary concern was to provide an acceptable course of action to permit withdrawal of mechanical ventilatory support for the purpose of organ donation for human transplant. In 1981, a US President’s Commission declared that individual death depended on either irreversible cessation of circulatory and respiratory functions or irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain. The consequent Uniform Determination of Death Act referred to ‘whole brain death’ as a requirement for the determination of brain death.13

Legislation that defined brain death and enabled beating-heart retrieval was enacted in New Zealand in 1964 and in Australia from 1982. This legislation heralded the establishment of formal transplant programs. In Australia, the first heart and lung program commenced in 1983, a liver transplant program in 1985, combined heart–lung transplant in 1986, combined kidney and pancreas in 1987, single lung in 19902,3 and small bowel in 2010. In New Zealand, bone was first transplanted in the early 1980s and the first heart transplant occurred in 1987. Skin transplantation occurred in 1991, lung transplantation in 1993, and liver and pancreas transplantation in 1998.4 The success of transplantation in the current era as a viable option for end-stage organ failure is primarily due to the discovery of the immunosuppression agent cyclosporin A.5

‘Opt-In’ System of Donation in Australia and New Zealand

There are currently two general systems of approach to seeking consent for cadaveric organ and tissue donation in operation around the world. Some countries (e.g. Spain, Singapore and Austria) have legislated an ‘opt out’, or presumed consent, system, where eligible persons are considered for organ retrieval at the time of their death if they have not previously indicated their explicit objection (see Table 27.1). In Australia, New Zealand, the US, the UK and most other common-law countries, the approach is to ‘opt in’, with specific consent required from the potential donor’s next of kin.6,7 In some states of Australia (for example, New South Wales and south Australia) and in New Zealand people indicate consent to organ donation on their driver’s licence or the Australian Organ Donor Register.8,9,10 In Singapore, the Human Organ Transplant Act of 1987 combines a presumed consent system with a required consent system for the Muslim population. The informed consent legislations of Japan and Korea are two of the most recent to come into force, in 1997 and 2000 respectively; before then, only living donation and donation after cardiac death were possible.11,12

| Country | Type of legislation | Year and description of legislation |

|---|---|---|

| Australia | Informed consent | 1982, donor registry since 2000 |

| Austria | Presumed consent | 1982, non-donor register since 1995 |

| Belgium | Presumed consent | 1986, combined register since 1987, families informed and can object to organ donation |

| Bulgaria | Presumed consent | 1996, in practice, consent from family required |

| Canada | Informed consent | 1980 |

| Croatia | Presumed consent | 2000, family consent always requested |

| Cyprus | Presumed consent | 1987 |

| Czech Republic | Presumed consent | 1984 |

| Denmark | Informed consent | 1990, combined register since 1990, previously presumed consent |

| Estonia | Presumed consent | no date identified |

| Finland | Presumed consent | 1985 |

| France | Presumed consent | 1976, non-donor register since 1990; families can override the wishes of the deceased |

| Germany | Informed consent | 1997 |

| Greece | Presumed consent | 1978 |

| Hungary | Presumed consent | 1972 |

| India | Informed consent | 1994 |

| Ireland | Informed consent | follows UK legislation |

| Israel | Presumed consent | 1953 |

| Italy | Presumed consent | 1967, combined register since 2000, families consulted before retrieval |

| Japan | Informed consent | 1997 |

| Latvia | Presumed consent | no date identified |

| Korea | Informed consent | 2000 |

| Lithuania | Informed consent | no date identified |

| Luxemburg | Presumed consent | 1982 |

| The Netherlands | Informed consent | 1996, combined register since 1998 |

| New Zealand | Informed consent | 1964 |

| Norway | Presumed consent | 1973, families consulted and can refuse |

| Poland | Presumed consent | 1990, non-donor register since 1996 |

| Portugal | Presumed consent | 1993, non-donor register since 1994 |

| Romania | Informed consent | 1998, combined register since 1996 |

| Singapore | Presumed consent | 1987, informed consent for Muslim population |

| Slovak Republic | Presumed consent | 1994 |

| Slovenia | Presumed consent | 1996 |

| Spain | Presumed consent | 1979, in practice, consent required from families |

| Sweden | Presumed consent | 1996, families can veto consent if wishes of the deceased are not known; previously informed consent |

| Switzerland | Informed consent | 1996, some Cantons have presumed consent laws |

| Turkey | Presumed consent | 1979, in practice, written consent required from family |

| United Kingdom | Informed consent | 1961, donor register since 1994 |

| United States | Informed consent | 1968, donor registers in some states |

Note: A combined register is a register of consent and refusal.

Types of Donor and Donation

Organ and tissue donation includes retrieval of organs and tissues both after death and from a living person. Donations from a living person include regenerative tissue (blood and bone marrow) and non-regenerative tissue (cord blood, kidneys, liver (lobe/s), lungs (lobe/s), femoral heads). The implications of consent are different for each type of requested tissue. For example, the collection of bone marrow, retrieval of a kidney, the lobe of a liver or lung are invasive procedures that could potentially risk the health and wellbeing of the donor.14 In contrast, donation of a femoral head could be the end-product of a total hip replacement, where the bone is otherwise discarded. Similarly, cord blood from the umbilical cord is discarded if not retrieved immediately after birth.

Organ Donation and Transplant Networks in Australasia

As part of the national reform package for the organ and tissue donation and transplantation sector, all state and territory health ministers agreed to the establishment of a national network of organ and tissue donation agencies, namely the Organ and Tissue Authority. This involved the employment of specialist hospital medical directors and senior nurses to manage the process of organ and tissue donation as dedicated specialist clinicians employed within the intensive care unit.1

The responsibility for leading this group of dedicated health professionals rests with the National Medical Director who supports this team through a Community of Practice (CoP) Program. This community of health professionals, along with the staff of the Authority, are the DonateLife Network, working together to share information, build on existing knowledge, develop expertise and solve problems in a collaborative and supported manner.1

The Organ and Tissue Authority

The Organ and Tissue Authority is the peak body that works with all jurisdictions and sectors to provide a nationally coordinated approach to organ and tissue donation for transplantation to maximise rates of donation. The role of the Authority is to ‘spearhead and be accountable for a new world’s best practice national approach and system to achieve a significant and lasting increase in the number of life-saving and life-transforming transplants for Australians’.1

The Authority was established in 2009 under the Australian Organ and Tissue Donation and Transplantation Authority Act 2008 as an independent statutory authority within the Australian Government Health and Ageing portfolio. The DonateLife Network, under the Authority, include ‘DonateLife’ agencies and hospital-based staff across Australia dedicated to organ and tissue donation. DonateLife agencies were re-formed and re-named as a nationally integrated network to manage and deliver the organ donation process according to national protocols and systems and in collaboration with their hospital-based colleagues.1 Legislation in New Zealand is national, with Organ Donation New Zealand coordinating all organ and tissue retrieval from deceased donors.4

Regulation and Management

In Australia, quality processes involved in organ and tissue retrieval and transplant are governed by the Therapeutics Goods Administration.15 In New Zealand there is currently an unregulated market for medical devices and complementary medicines, although an agreement to establish a Joint Scheme for the Regulation of Therapeutic Products between the Governments of Australia and New Zealand is in place.15

The process of potential donor identification and management in critical care is directed by the Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society (ANZICS).13 Education of health professionals is facilitated by the Australasian Donor Awareness Program (ADAPT), in association with the Australian College of Critical Care Nurses (ACCCN) and the College of Intensive Care Medicine (CICM).

Donor criteria and organ allocation is regulated by the Transplantation Society of Australia and New Zealand (TSANZ). Donor and recipient data are collated by the Australia and New Zealand Organ Donation Registry (ANZOD Registry). Professional groups related to this specialty area also cover both countries. The Australasian Transplant Coordinators Association (ATCA) is composed of clinicians working as donor and/or transplant coordinators, and the Transplant Nurses Association (TNA) is a specialty group for nurses working with transplant recipients (see Online resources).

Identification of Organ and Tissue Donors

The four main factors that directly influence the number of multi-organ donations are:

Brain Death

The incidence of brain death determines the size of the potential organ donor pool. Diagnosis of brain death is now widely accepted, and most developed countries have legislation governing the definition of death and the retrieval of organs for transplant.16 In Australia and New Zealand the most common cause of brain death has changed from traumatic head injury to cerebrovascular accident, which has implications for the organs and tissues retrieved as donors are older and often have cardiovascular and other co-morbidities.17 There is no legal requirement to confirm brain death if organs and tissues are not going to be retrieved for transplant.13

Two medical practitioners participate in determining brain death; in Australia one must be a designated specialist. Brain death is observed clinically only when the patient is supported with artificial ventilation, as the respiratory reflex lost due to cerebral ischaemia will result in respiratory and cardiac arrest. Artificial (mechanical) ventilation maintains oxygen supply to the natural pacemaker of the heart that functions independently of the central nervous system. Brain death results in hypotension due to loss of vasomotor control of the autonomic nervous system, loss of temperature regulation, reduction in hormone activity and loss of all cranial nerve reflexes. Table 27.2 lists the conditions commonly associated with brain death. Irrespective of the degree of external support, cardiac standstill will occur in a matter of hours to days once brain death has occurred.13,18

| Condition | Incidence |

|---|---|

| Hypotension | 81% |

| Diabetes insipidus | 53% |

| Disseminated intravascular coagulation | 28% |

| Arrhythmias | 27% |

| Cardiac arrest | 25% |

| Pulmonary oedema | 19% |

| Hypoxia | 11% |

| Acidosis | 11% |

Role of Designated Specialists

According to Australian law, senior medical staff eligible to certify brain death using brain death criteria must be appointed by the governing body of their health institution, have relevant and recent experience, and not be involved with transplant recipient selection. The most common medical specialties appointed to the role are intensivists, neurologists and neurosurgeons in metropolitan centres, and general surgeons or physicians in rural settings.17

In New Zealand the role is not appointed although medical staff confirming brain death must also act independently; neither can be members of the transplant team, and both must be appropriately qualified and suitably experienced in the care of such patients.13 The New Zealand Code of Practice for Transplantation19 also recommends that the medical staff not be involved in treating the recipient of the organ to be removed, and one of the doctors should be a specialist in charge of the clinical care of the patient.

Testing Methods

The aim of testing for brain death is to determine irreversible cessation of brain function. Testing does not demonstrate that every brain cell has died but that a point of irreversible ischaemic damage involving cessation of the vital functions of the brainstem has been reached. There are a number of steps in the process, the first being the observation period. An observation period of at least 4 hours from onset of observed no response is recommended before the first set of testing commences, in the context of a patient being mechanically ventilated with a Glasgow Coma Scale score of three, non-reacting pupils, absent cough and gag reflexes and no spontaneous respiratory effort.13 The second step is to consider the preconditions (see Box 27.1). Once the observation period has passed (during which the patient receives ongoing treatment) and the preconditions have been met, formal testing can occur.

Box 27.1

Preconditions of brain death testing13

Practice tip

When testing for corneal reflex, take care not to cause corneal abrasion, which might preclude the cornea from being transplanted if the patient is an eye donor. Invite the next of kin to observe the second set of clinical tests to assist their comprehension of brain death. Assign a support person to be with the family to assist in explaining and interpreting the testing process.84

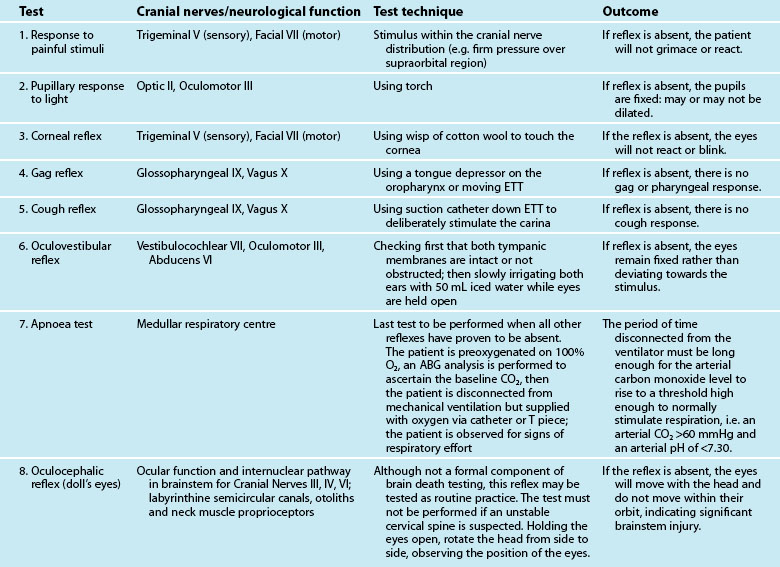

Formal testing for brain death is undertaken using either clinical assessment or cerebral blood flow studies.13 Clinical assessment of the brainstem, involving assessment of the cranial nerves and the respiratory centre (see Table 27.3) is the most common approach to testing. Brain death is confirmed if there is no reaction to stimulation of these reflexes, with the respiratory centre tested last and only if the other reflexes prove to be absent. If the patient demonstrates no response to the first set of tests, after a recommended observation period of at least 2 hours, the tests are repeated to demonstrate irreversibility.13

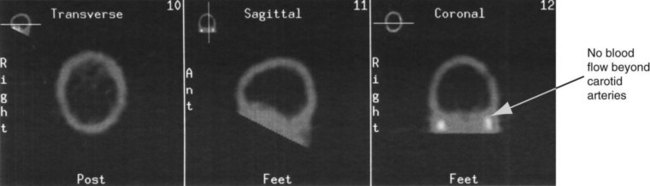

If the preconditions outlined in Box 27.1 cannot be verified, brain death can be confirmed using cerebral blood flow imaging to demonstrate absent blood flow to the brain, by either contrast angiography or radionuclide scanning. Contrast angiography can be performed by direct injection of contrast into both carotid arteries and one or both of the vertebral arteries, or via the vena cava or aortic arch. Brain death is confirmed when there is no blood flow above the carotid siphon13,20–22 (see Figure 27.1). A radionuclide scan is performed by administering a bolus of short-acting isotope intravenously or by nebuliser while imaging the head using a gamma camera for 15 minutes. No intracranial uptake of isotope confirms absent blood flow to the brain13,20–22 (see Figure 27.2).

If brain death is confirmed, the time of death is recorded as the time of certification of the testing result (i.e. at the completion of the second set of clinical tests, or the documentation of the results of the cerebral blood flow scan).13

Identification of a Potential Multiorgan Donor

The second factor influencing the number of actual organ donors is identification of a potential donor. A potential donor is defined in this situation as a patient who is suspected of, or is confirmed as, being brain dead. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for organ and tissue donation are constantly being reviewed and refined.23 Advice can be sought at any stage when considering the medical suitability of potential organ donors, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, from respective state and territory organ donation agencies (see Online resources).

Seeking Consent

The third factor influencing the number of donors is the consent-seeking process. Common practice in Australia and New Zealand is for the treating medical staff either to initiate or at least to be involved in approaching the next of kin after death has been confirmed.13,24 Approaching the next of kin to seek consent is part of the duty of care to patients who may have indicated their wish to be a donor at the time of their death.13,25,26 The act of offering the option of organ donation can also be considered part of the duty of care to the family.13 This view is supported by a survey of donor families, who indicated that they were grateful to have been provided with the option.27,28,31 Three elements are involved when approaching a family regarding the option of organ donation:

1. their knowledge, beliefs and attitudes

2. their in-hospital experience29

3. any beliefs and biases of health professional/s conducting the approach.30

The outcome of an approach cannot be predicted or anticipated, as it may affect the ‘spirit’ in which the approach is made; a large US study demonstrated that clinical staff were incorrect 50% of the time when asked to predict the response of a next of kin.31

Influence of knowledge, beliefs and attitudes

Attitudes to organ donation are influenced by spiritual beliefs, cultural background, prior knowledge about organ donation, views on altruism and prior health experiences.32 Next of kin consider two aspects associated with existing attitudes and knowledge: the decision maker(s)’ own thoughts and feelings; and the previous wishes and beliefs of the person on whose behalf they are making the decision. There is evidence of a link between consent rates and prior knowledge of the positive outcomes of organ donation.33,34

Delivery of relevant information

An important consideration for all health professionals is that family members may have a diminished ability to receive and understand information because of their stress and psychological responses at this time of family crisis.35,36 As interviews held with the family are the foundation of the entire organ donation and transplant process,37 the discussion about brain death must be clear and emphatic, using language free of medical terminology, and include an explanation of the physical implications.38,39 Diagrams, analogies, scans and written materials have been suggested as useful aids for enhancing understanding by next of kin.25,40,41 One approach was to describe brain death as like a jigsaw puzzle with a piece missing, to illustrate the relationship of the brain to the rest of the body.41 Opportunities for staff to train and role-play this scenario with programs like ADAPT (see Online resources) improves the likelihood of meeting the needs of families.38,42–44

As the time of confirmation of brain death is the person’s legal time of death, a discussion is held with the family to discuss their options and associated implications. Options are to: (1) cease ventilation and allow cardiac standstill to occur; or (2) maintain ventilation and haemodynamic support to facilitate viable organ and tissue donation. The retrieval process must be fully explained to ensure an informed decision, but not to overload the next of kin.25,45 Table 27.4 lists some aspects of the organ donation process that could be included in such a discussion. As information given to a family contains both good news and bad news it is suggested to start with the good news – the benefits of donation, the right of the family to refuse consent, and the lack of cost; then move to the bad news – the reality of the surgical intervention and the lack of guarantee that the organs will be transplanted.45 Of note, a best practice approach aims to assist the family to make the decision that is ‘right’ for them and does not necessarily result in gaining consent.

TABLE 27.4 Information about the organ donation process and retrieval to assist in informed decision making85

| Decision | Issues |

|---|---|

| Ensure that the next of kin (NOK) have understanding of: |

• They will not be with the donor at time of cardiac arrest.

• Donor will remain in critical care, monitored and ventilated until going to theatre for retrieval.

• Explain the organ retrieval surgery, including the presence of an anaesthetist to monitor the haemodynamics and ventilation. Explain to the family that the person no longer feels any pain, so an anaesthetic is not given.

• Discuss which organs and tissue would be potentially medically suitable for retrieval for transplant.

• NOK can give specific consent; they are not obliged to grant global consent.

• Only named organs and tissues with consent are retrieved.

• Advise expected length of process.

• Explain reason for bloods being taken and stored.

• Advise that a coordinator will be present through the entire process.

• Explain how the donor will look after the retrieval.

• Organ donation will not delay funeral plans.

• Provide copy of consent form.

• Explain privacy implications of Human Tissue Act, for donor family and transplant recipients.

• Explain reasons why donation may not proceed.

• Explain that organs may be transplanted interstate.

• In the event of an abnormality/diseases, organs will not be retrieved.

• Explain consent for research: offer copy of research page.

• The site designated officer will also sign the consent form.

Meetings with the family

The timing, location, content and process of discussions with the family are all important considerations. An effective protocol for communicating with the family of potential donor must include: (1) frequent and honest updates on the patient’s prognosis; (2) clear explanation of brain death; (3) the option of organ donation not raised until the family accepts that the patient is dead; (4) conversations held in a private and quiet setting;32,47–50 and (5) involvement of an organ donation professional with a clear definition of roles.32

There is compelling evidence that the meeting confirming diagnosis of brain death should be held separately or decoupled from the conversation about the option of organ and tissue donation.31,34,47–50 In reality, the pace and flow of discussions should be assessed on a case-by-case basis, as there may be circumstances when the discussion about organ donation is appropriately held prior to the confirmation of death.13,25,46

1. Use of inappropriate terms like ‘harvest’ to name the organ retrieval surgery (this is considered extremely harsh and undignified) and ‘life support’ to name the ventilator (this could perpetuate the hope of a chance of survival or recovery).13,26,36,41,51

2. Attire of the personnel involved: staff wearing surgical scrubs or plastic aprons made families wonder what was being done to their relatives that required health professionals to be wearing such clothing; and donor coordinators not wearing uniforms were easier to speak to.41

3. Timing or use of the information from consent indicator sources like organ donor registers and the driver’s licence. If staff come to the discussion ‘armed’ with this information, it could be seen as coercive and disrespectful, so some caution and discretion about the introduction and use of this information is recommended.41

Staff roles, delineation and involvement

Staff involved in the explanation of brain death must have a clear understanding of brain death themselves before attempting to explain it to a family.49 The process of organ and tissue donation in critical care is significant for all concerned. When death is confirmed it marks the end of an episode that has been catastrophic for both patient and loved ones, and a potentially stressful and exhausting experience for staff.40,52–55 Approaching a potential donor family is a multidisciplinary team effort, and guidelines encourage treating medical staff to continue their involvement with patient and family after brain death is confirmed, for continuity of care.13 Nursing staff involvement in the process of organ and tissue donation is central and intrinsic, including the practicalities of the process, and care of the potential donor and family during the decision-making process.56 Donor families have identified nurses as being the most helpful health professionals in providing information and emotional support.13,27,51,57

A holistic approach to supporting families in critical care also includes involvement of social workers and pastoral care workers and other allied health professionals. Often these health professionals have been working with the family for a number of days and act as confidants and a resource for information on issues such as implications of a coronial enquiry and a religious denomination’s stance on organ donation. Most major religions are supportive of organ and tissue donation for transplant and would instruct the family to make the decision that they felt was correct.1,58

Donatelife Organ donor coordinator

The ‘Donatelife’ organ donor coordinator acts as a resource and is invited into critical care when appropriate.1,58 A professional who is an expert in donation and has the time to spend with the family may be the best person to undertake an approach to a potential donor family.49 A large US study found that consent rates improved when conversations about brain death and organ donation were separated, were held in a private setting and when an organ donation professional/trained requestor was involved.48

Documentation of Consent

Definition of Next of Kin

In Australia the definition of next of kin for adults and children is listed in strict order (see Table 27.5). In New Zealand there is no hierarchy of next of kin, with the definition including a surviving spouse or relative.13 In both countries, the next of kin can override the known wishes of the deceased regarding consent, but experience shows that the family rarely disagree if the wishes of the deceased are known.13

TABLE 27.5 Definition of next of kin for children and adults in Australian legislation13

| Donor | Order of seniority | Relationship |

|---|---|---|

| Child | 1 | Parent |

| 2 | Adult sibling (over 18 years) | |

| 3 | Guardian (immediately before death) | |

| Adult | 1 | Spouse or de facto (at time of death) |

| 2 | Adult offspring (over 18 years) | |

| 3 | Parent | |

| 4 | Adult sibling (over 18 years) |

Role of Designated Officers

Under Australian law, a ‘designated officer’ is appointed by the governing body of the institution to authorise a non-coronial postmortem and the removal of tissue from a deceased person for transplant or other therapeutic, medical or scientific purposes.13 The designated officer must be satisfied that all necessary inquiries have been made and any necessary consent has been obtained before granting authority. Medical, nursing and administrative staff can be appointed to the role, but they must not act in a case if they have had clinical or personal involvement in the donor’s case.13

The term ‘designated officer’ is not used in New Zealand legislation. A person with equivalent authority under the Human Tissue Act 2008 is the person lawfully in possession of the body.59 In the case of a hospital, this person is specified as the medical officer in charge.13 In practice, the treating clinician undertakes this consultation with the family.

Role of Coroner and Forensic Pathologists

Because of the nature of their death, many donors are subject to coronial inquiry. In this case, permission to undertake organ and tissue retrieval is sought from the respective forensic pathologist and coroner according to local policy and procedure as part of the consent-seeking process. The coronial system is very supportive of donation for transplant, and in 2009, 43% of the Australian and 44% of New Zealand multiorgan donors were coroner’s cases.17

Consent Indicator Databases

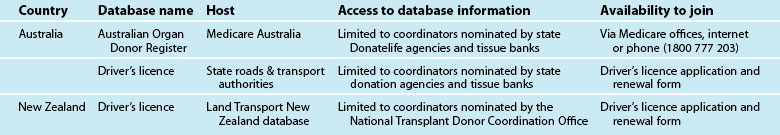

The most influential variable that an individual may have on family unit decision-making is the existence of an advance care directive or prior indication of consent, as this information has made decision-making ‘easier’60,61 and preserved patient autonomy,50,62 enabling wishes of the patient to be followed even when family decision makers would have made the opposite decision. Conversely, if the family members were opposed to donation despite the presence of an indication of consent from the potential donor, the retrieval would not occur on ethical grounds.40 Table 27.6 lists prospective donation databases available in Australia and New Zealand.

Cultural Competence

With large cultural mixes in the Australian and New Zealand populations, best practice for approaching a family includes openness and awareness of what information the family member(s) may need to make their decision. As significant differences also exist within various cultural groups, expectations of responses cannot be stereotyped. When healthcare professionals are unsure of how a family may perceive a situation it is best to ask, as acknowledgment of expectations and needs can lead to improved communication.63 Importantly, the most significant differences between potential donor families are socioeconomic and educational factors, rather than cultural or racial background.64 Therefore, individual assessment must guide the approach by health professionals.

Organ Donor Care

Time is critical in the management of a potential organ donor. Those patients who have sustained traumatic brain injuries deteriorate rapidly following brain death, exhibiting severe physiological instability requiring vigilant monitoring and specialised treatment to maintain organ perfusion. This is a time of great distress for families with the patient’s death usually the result of a sudden, unexpected illness or injury and therefore discussion surrounding organ and tissue donation must be undertaken in a sensitive manner by skilled requestors who possess a strong professional commitment to the quality of the process.13,36

Ideally, the time between brain death and organ retrieval should be minimised to ensure an optimal outcome for transplant recipients. Therefore the focus of medical management changes from ensuring brain perfusion to maintaining good organ perfusion for transplantation.36 Early referral, application of recognised management protocols and collaboration between the donation centre and retrieval teams is paramount. Donor family care forms a crucial part of the process, with up-to-date and accurate information essential to ensure the bereavement process is managed appropriately.

Referral of Potential Donor

If consent is granted, the referral process usually commences immediately. To ensure organ viability for transplant, the time from brain death confirmation to retrieval of organs is kept to a minimum. The longer the time delay, the more likely that organ failure-related complications will occur.65 In 2009, the median time from brain death confirmation to the commencement of organ retrieval was 16 hours in Australia and 12 hours in New Zealand.17

The referral process begins with the donor coordinator collating the past and present medical, surgical and social history of the potential donor, and relaying this information to the relevant transplant units (see Table 27.7). Using this information, transplant teams allocate the organs to the most suitable and appropriate recipient/s. If the transplant team does not have a suitable recipient, the offer is extended to another team in Australia or New Zealand on rotation using TSANZ guidelines.23

| Section | Details |

|---|---|

| Personal details | Address, phone number, sex, age, height, weight, race, religion, build, occupation |

| Current admission details | Dates and time of hospital admission, intubation, critical care admission Other trauma or significant event |

| Declaration of brain death | Cause of death, time, date, method of testing |

| Consent details | Which organs, designated officer details, coroner’s details, police details, who gave consent, which databases accessed |

| Donor history | Family, medical, surgical, travel, social and sexual history |

| Blood results | Blood group, biochemistry and haematology on admission and within past 12 hours, microbiology, gas exchange |

| Test results | Chest X-ray including lung field measurements, ECG, echocardiogram, bronchoscopy, sputum |

| Haemodynamics | BP, MAP, HR, CVP, temperature |

| Admission history | Cardiac arrest, temperature, renal function, nutrition, drug and fluid administration |

| Physical examination | Scars, trauma, needle marks, etc. |

Tissue Typing and Cross-Matching

A vital component of the assessment and referral process is tissue typing, cross-matching and virology testing of the potential donor’s blood. Blood is taken from an arterial or central line of the potential donor and sent to the relevant accredited laboratory (see Table 27.8). Tissue typing identifies the human leucocyte antigen (HLA) phenotype from the genes on chromosome 6. The HLA molecules control actions of the immune system to differentiate between ‘self ’ and foreign tissue, and initiate an immune response to foreign matter. As a transplanted organ will always be identified as foreign tissue by the recipient’s body, the use of immunosuppressive drugs suppress the immune response. A crossmatch is routinely used to predict the level of this response. Lymphocytes from the potential donor are added to the potential recipient’s serum to test whether the recipient has an antibody that is specific to the donor’s HLA antigens. A positive crossmatch reaction, where the recipient’s serum destroys the donor’s cells, is a contraindication for transplantation.58

TABLE 27.8 Blood tests required for organ donation58,72,87,88,89

| Measurement required | Test |

|---|---|

| Serology |

Donor Management

The fourth factor influencing the number of actual organ donors is the clinical management that the donor and family receive after confirmation of death. The aim of donor management is to support and optimise organ function until organ retrieval commences, while maintaining dignity and respect for the donor and support for the family. All aspects of ICU treatment, apart from brain-oriented therapy, should continue until it is certain that organ donation will not occur.13 Ideal parameters for biochemistry, vital signs, and urine output and clinical management are detailed in Box 27.2.

Box 27.2

Medical management of the potential donor76

• Refer all potential organ donors to the local State DonateLife agency, even if uncertain of medical suitability. Criteria for suitability change over time and vary according to recipient circumstances.

• Maintain MAP > 70 mmHg: maintain euvolaemia, if required administer inotropic agents (e.g. noradrenaline)

• Maintain adequate organ perfusion (monitor urine output, lactate), consider invasive haemodynamic monitoring

• Monitor electrolytes (Na+, K+) every 2 to 4 hours and correct to normal range

• Suspected diabetes insipidus (UO >200 mL/h, rising serum sodium): administer DDAVP (e.g. 4 mcg IV in adults) and replace volume loss with 5% dextrose

• Treat hyperglycaemia (actrapid infusion): aim blood glucose 5 to 8 mmol/L

• Keep temp >35°C. Pre-emptive use of warming blankets etc is advised as hypothermia may be difficult to reverse once it has developed

• Provide ongoing respiratory care (frequent suctioning, positioning/turning, PEEP, recruitment manoeuvres)

Retrieval Surgery

Organ retrieval surgery occurs in the hospital where the donor is located, with the local operating theatre staff integral to the process. The donor is transferred to theatre after routine preoperative checks and documentation is completed, including death certification and consent for organ and tissue retrieval. All documentation, particularly consent, is viewed by all members of the retrieval surgical team before surgery commences. Depending on which organs are to be retrieved, the retrieval teams will be tasked to abdominal organs and thoracic organs, and will bring most of their specialised equipment with them. An anaesthetist monitors haemodynamics, ventilation and administers medications, which may include a long-acting muscle relaxant given prior to the surgical procedure, to prevent interference in the surgical process by spinal reflexes, only after consultation with the retrieval team.58 No other anaesthetic agents are administered. The local scrub staff will work with the visiting surgical teams, and the Donatelife donor coordinator will be present to document the procedure and outcomes, and act as resource for all staff present.

Surgery may take 4–5 hours depending on the extent of the retrieval; cross-clamp will occur once the surgeons have identified all the various anatomical points. The aorta is cross-clamped with vascular clamps below the diaphragm and at the aortic arch, the heart is stopped and ventilation is ceased. Retrieval teams administer a cold perfusion fluid with an electrolyte mix specific to the organs being retrieved, and remove the organs. Organs are bagged with sterile ice and perfusion fluid and transported by the retrieval teams to the transplanting hospitals. The donor’s surgical wound, from the sternal notch to the pubis, is closed by the surgeons in a routine manner and dressed with a surgical dressing. If the donor is not a coroner’s case, the remaining lines, catheter and drains are removed according to local policy, the patient is washed, and arrangements are made to transfer the patient to a location for family viewing or to the mortuary. Musculoskeletal tissue and retinal retrieval can occur after the solid organ retrieval in theatre or later in the mortuary.66,67

Donor Family Care

Supportive care of a donor family begins from the time their family member is admitted to hospital and continues beyond organ retrieval. In addition to personal factors such as cultural background, family dynamics, coping skills and prior experiences with loss that may influence the grieving process, the family of an organ and tissue donor will be dealing with a number of unique factors. Death of their family member was possibly sudden and unexpected; brain death can be difficult to understand when people look as if they are asleep rather than dead; having the option of organ donation may mean making a decision on behalf of the person if his/her wishes were not known; and the process of organ donation means they will not be with the person when their heart stops.68

Donor families benefit from emotional and physical support throughout and after the organ donation process. In critical care units, this support can include open visiting times, privacy for meetings, clear and precise information and regular contact with the attending clinical team and the Donatelife donor coordinator. After organ retrieval, ongoing care can include contact with a bereavement specialist, written material, telephone support, private or group counselling, and correspondence from recipients.66 Most Australian and New Zealand organ donation agencies have cost-free structured aftercare and follow-up programs with these features (see Online resources). Involvement of trained personnel with a donor family through this process can positively influence the family’s grief journey.51

The National Donor Family Support Service operates through the DonateLife Network and is a nationally consistent program of support that provides cadaveric organ and/or tissue donor families. All families whose next of kin are identified as possible donors are offered end-of-life support including bereavement counselling at the time, whether or not the potential donor proceeds to donation.1

Donation after Cardiac Death

Donation after cardiac death (DCD) (also known as non-heart-beating donor [NHBD]) provides a solid organ donation option for a patient who has not progressed and is not likely to progress to brain death. Prior to brain death legislation, donation after cardiac death was the source of cadaveric kidneys for transplant.69,70 Four categories of potential DCD donors have been identified (known as the Holland–Maastricht categories):71,72

1. dead on arrival (uncontrolled)

2. failed resuscitation (uncontrolled)

DCD programs around the world are being re-established, with successful retrieval and transplant of kidneys, livers and lungs.69 The Australian Organ and Tissue Authority has developed a national DCD protocol that outlines an ethical process that respects the rights of the patient and ensures clinical consistency, effectiveness and safety for both donors and recipients.1 Since 2005 there has been a steady increase in DCD donors each year, particularly in New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland and South Australia. Since 1989 there have been 131 donors in Australia and six donors in New Zealand.17 The first multiorgan DCD was performed in South Australia in 2006.

Identification of a Potential DCD Donor

Using lessons learnt from multiorgan donor programs, the aims of a successful DCD program are to maintain dignity for the donor at all times, provide the donor family with support and information, and limit warm ischaemia time (time from withdrawal of ventilation and treatment to confirmation of death to commencement of infusion of cold perfusion fluid and/or organ retrieval). Longer warm ischaemia time potentiates the risk of irreparable hypoxic damage to the organ.73 As noted above, Maastricht category 3 is the only option that can be controlled and possibly regulate warm ischaemia time. A potential category 3 DCD donor is a person ventilated and monitored in critical care about whom a decision has already made that further treatment is no longer of benefit, and current interventions are to be withdrawn. Clinical suitability assessment for organ retrieval replicates a multiorgan donor, with medical, surgical and social history, virology and organ function information collected. Legal requirements of the consent-seeking process also reflect those of a multiorgan donor. Potential donor families are informed that retrieval may not occur due to a number of factors, including the length of time from treatment withdrawal to cardiac standstill.73,74

Retrieval Process Alternatives

Withdrawal of treatment for a potential category 3 DCD patient can occur in critical care or in the operating theatre, depending on which organs are planned for retrieval. Death is determined by cessation of circulation, with recommendations that the ECG is not monitored (electrical activity can persist for many minutes following cessation of circulation), but an arterial line is used to determine the time of cessation of circulation.13 If withdrawal occurs in critical care, an intraabdominal catheter may be inserted via the femoral artery after cardiac standstill to infuse cold perfusion fluid into the abdominal cavity. If the lungs are to be retrieved, perfusion fluid is infused via bilateral intercostal catheters.69 The patient is then transferred to theatre for organ retrieval. When withdrawal of treatment occurs in theatre, a catheter is not required and retrieval may commence after the patient is declared deceased (cessation of circulation for greater than two minutes). If the patient does not die during the window of time available for organ retrieval, they are transferred back to ICU.74

Tissue-Only Donor

People confirmed as dead using cardiac criteria can be tissue donors. Eyes (whole and corneal button) are retrieved for cornea and sclera transplant. Musculoskeletal tissue is used for bone grafting (long bones of arms and legs, hemipelvis), urology procedures and treatment of sport injuries (ligaments, tendons, fascia and meniscus). Heart valves (bicuspid, tricuspid valves, aortic and pulmonary tissue) are used for heart valve replacement and cardiac reconstruction. Skin (retrieved from the lower back and buttocks) is used for the treatment of burns.75

Identification of Potential Tissue-Only Donor

After checking medical suitability and the relevant consent indicator database, a coordinator from the tissue bank or other trained personnel approach the next of kin with the option of tissue retrieval. Eyes can be retrieved up to 12 hours, and heart valves, skin and bone up to 24 hours after death. Of note, eye donors can be up to 99 years old, donors of heart valve up to 60 years and musculoskeletal up to 90 years of age.76 After tissue retrieval, every effort is made to restore anatomical appearance. Wounds are sutured closed and covered with surgical dressings, limbs given back their form, and eye shape is restored with the lids kept closed with eye caps.77,78 Support requirements for families of tissue-only donors share many aspects of programs provided for families of multi-organ donors. A sensitive approach, provision of adequate information to assist informed decision making, offers of bereavement counselling and follow-up information of recipient outcomes are evidence-based strategies of successful programs.1,79

Summary

There are three ‘types’ of organ or tissue donor:

1. multiorgan and tissue donor: after brain death has been confirmed

2. donor after cardiac death: controlled withdrawal of treatment in critical care/operating suite

Four factors directly influence the number of multiorgan donations:

• Medical suitability for every potential donor is assessed individually at the time of the person’s death.

• Support and guidance from donor agencies and tissue banks in Australia and New Zealand are available at all times.

• Care and support of the potential and actual donor family is a high priority for all donor agencies and tissue banks in Australia and New Zealand.

• Regular, routine follow-up and debriefing opportunities for critical care and operating theatre staff are important to manage stress reactions or other concerns.

Case study

Day 4

1430: Coroner grants permission for organ and tissue retrieval.

2000: Referral to transplant teams.

2015: Family completes formal identification with police for the coroner.

Research vignette

Learning activities

The following learning activities relate to the case study.

1. What constitutes eligibility for organ donation?

2. What methods are used to confirm brain death in Australia and New Zealand?

3. What are the ideal observation parameters for a potential multi-organ donor after brain death confirmation?

4. Who is the legal next of kin in the consent process?

5. Under which circumstances does the coroner need to be involved?

6. Will organ and tissue retrieval mutilate the body of the person?

7. What is the time frame from identification of the donor to actual organ retrieval?

Australasian Donor Awareness Program (ADAPT). www.adapt.asn.au.

Australasian Transplant Coordinators Association (ATCA). www.atca.org.au.

Australia & New Zealand Cardiothoracic Organ Transplant Registry. www.anzcotr.org.au/.

Australia & New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry (ANZDATA). www.anzdata.org.au.

Australia & New Zealand Intensive Care Society (ANZICS). www.anzics.com.au.

Australia & New Zealand Liver Transplant Registry. www.anzltr.org/.

Australia & New Zealand Organ Donation Registry (ANZOD). www.anzdata.org.au/ANZOD.

Australian Bone Marrow Registry. www.abmdr.org.au/.

Australian Corneal Graft Registry. www.flinders.edu.au/medicine/sites/ophthalmology/clinical/the-australian-corneal-graft-registry.cfm.

Australian Tissue Banking Forum. www.atbf.org.au.

Australian College of Critical Care Nurses (ACCCN). www.acccn.com.au.

Australian Organ Donor Register. www.medicareaustralia.gov.au/organ.

Australian Practice Nurses Association. www.apna.asn.au.

Clinician Development and Education Service – Queensland Health. cdes.learning.medeserv.com.au/portal/browse_CDES/index.cfm.

DonateLife. www.donatelife.gov.au.

Donor Tissue Bank of Victoria. www.vifm.org/n135.html.

gplearning. www.gplearning.com.au.

Eye Bank of South Australia. www.flinders.edu.au/medicine/sites/ophthalmology/clinical/#eye.

Lions Corneal Donation Service. cera.clientstage.com.au/our-work/lions-eye-donation-service.

Lions Eye Bank (WA). www.lei.org.au/go/lions-eye-bank.

Lions NSW Eye Bank. www.eye.usyd.edu.au/eyebank.

National Organ Donation Collaborative (NODC). www.nhmrc.gov.au/nics/programs/nodc/index.htm#trans.

New Zealand National Transplant Donor Coordination Office. www.donor.co.nz.

New Zealand National Eye Bank. www.eyebank.org.nz.

Perth Bone and Tissue Bank. www.perthbonebank.com.

Queensland Bone Bank. www.health.qld.gov.au/queenslandersdonate/banks/bone.asp.

Queensland Eye Bank. www.health.qld.gov.au/queenslandersdonate/banks/eye.asp.

Queensland Heart Valve Bank. www.health.qld.gov.au/queenslandersdonate/banks/heart_valve.asp.

Transplant Nurses’ Association (TNA). www.tna.asn.au.

Transplantation Society of Australia and New Zealand (TSANZ). www.racp.edu.au/tsanz.

Australian College of Critical Care Nurses. ACCCN position statement on organ and tissue donation and transplantation. www.acccn.com.au/content/view/34/59, 2009. Available from

National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). National protocol for donation after cardiac death. Canberra: NHMRC; 2010. Available from www.donatelife.gov.au/

Russ GR. Organ Donation in Australia: international comparisons. n.d. Available from: www.donatelife.gov.au/

Snell GI, Levvey BJ, Williams TJ. Non-heart beating organ donation. Internal Med J. 2004;34:501–503.

1 DonateLife website. [Cited Aug 2010]. Available from http://www.donatelife.gov.au/The-Authority/About-us/Our-role.html

2 Chapman JR. Transplantation in Australia – 50 years in progress. Med J Aust 1992; 157(1): 46–50.

3 McBride M, Chapman JR. An overview of transplantation in Australia. Anaesth Intens Care. 1995;23(1):60–64.

4 Organ Donation New Zealand website. [Cited Aug 2010]. Available from www.donor.co.nz/donor/transplants/history.php

5 Borel JF, Feurer C, Gubler HU, Stahelin H. Biological effects of cyclosporin-A: a new antilymphocytic agent. Agents Actions. 1976;6:468–475. July

6 Kelly M. ‘Opting-out’ vs ‘Hot Pursuit’– organ donation and the family. Bioethics Outlook – John Plunkett Centre Ethics Health Care. 1996;7(2):1–6.

7 Dickens BC, Fluss SS, King AR. Legislation on organ and tissue donation. In: Chapman JR, Deierhoi M, Wight C. Organ and tissue donation for transplantation. London: Arnold; 1997:95–119.

8 Medicare Australia. Australian Organ Donor Register. [Cited Aug 2010]. Available from www.medicareaustralia.gov.au/organ

9 Motoring SA website. [Cited Aug 2010]. Available from www.sa.gov.au/subject/Transport,+travel+and+motoring/Motoring

10 Roads and Traffic Authority website. [Cited Aug 2010]. Available from www.rta.nsw.gov.au/

11 Kim JR, Elliott D, Hyde C. The influence of sociocultural factors on organ donation and transplantation in Korea: findings from key informant interviews. J Transcult Nurs. 2004;15(2):147–154.

12 Kita Y, Aranami Y, Aranami Y, Nomura Y, Johnson K, et al. Japanese organ transplant law: a historical perspective. Prog Transplant. 2000;10(2):106–108.

13 Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society (ANZICS). The ANZICS Statement on Death and Organ Donation (Edition 3.1). Melbourne: ANZICS; 2010.

14 Gleeson G. Organ transplantation from living donors. Bioethics Outlook – Plunkett Centre Ethics Health Care. 2000;11(1):5–8.

15 Therapeutic Goods Administration website. [Cited Jul 2010]. Available from http://www.anztpa.org/

16 Pearson IY. The potential organ donor. Med J Aust. 1993;158(1):45–47.

17 Australia and New Zealand Organ Donation Registry (ANZOD). Registry Report 2010. Adelaide: ANZOD; 2010.

18 Power BM, Van Heerden PV. The physiological changes associated with brain death: current concepts and implications for treatment of the brain dead organ donor. Anaesth Intens Care. 1995;23(1):26–36.

19 New Zealand Ministry of Health (NZMH). A code of practice for transplantation of cadaveric organs. Wellington: NZMH; 1987.

20 Monsein LH. The imaging of brain death. Anaesth Intens Care. 1995;23(1):44–50.

21 Tortora GJ, Grabowski SR. The principles of anatomy and physiology, 9th edn, New York: Wiley, 2000.

22 General Electric Healthcare. Medcyclopaedia: Standard edition. [Cited July 2006]. Available from http://www.medcyclopaedia.com/library/topics/volume_ii/c/carotid_siphon.aspx

23 The Transplantation Society of Australia and New Zealand Inc (TSANZ) website. [Cited Aug 2010]. Available from www.racp.edu.au/tsanz/

24 Thompson JF, Hibberd AD, Mohacsi PJ, Chapman JR, MacDonald GJ, Mahony JF. Can cadaveric donation rates be improved? Anaesth Intens Care. 1995;23(1):99–102.

25 Raper RF, Fisher MM. Brain death and organ donation – a point of view. Anaesth Intens Care. 1995;23(1):16–19.

26 Streat S. Clinical review: moral assumptions and the process of organ donation in the intensive care unit. [Cited Jan 2005]. Available from http://ccforum.com/inpress/cc2876, 2004.

27 Pelletier ML. The needs of family members of organ and tissue donors. Heart Lung. 1993;22(2):151–157.

28 Australasian Transplant Coordinators Association (ATCA). National donor family study: 2004 report. Melbourne: ATCA; 2004.

29 Beasley CL. Maximizing donation. Transplant Rev. 1999;13(1):31–39.

30 Verble M, Worth J. Biases among hospital personnel concerning donation of specific organs and tissues: implication for the donation discussion and education. J Transplant Coord. 1997;7(2):72–77.

31 Evanisko MJ, Beasley CL, Brigham LE, Capossela C, Cosgrove GR, et al. Readiness of critical care physicians and nurses to handle requests for organ donation. Am J Crit Care. 1995;7(1):4–12.

32 Verble M, Worth J. Fears and concerns expressed by families in the donation discussion. Prog Transplant. 2000;10(1):48–55.

33 Pearson IY, Bazeley P, Spencer-Plane T, Chapman JR, Robertson P. A survey of families of brain dead patients: their experiences, attitudes to organ donation and transplantation. Anaesth Intens Care. 1995;23(1):88–95.

34 DeJong W, Franz HG, Wolfe SM, Nathan H, Payne D, et al. Requesting organ donation: an interview study of donor and nondonor families. Am J Crit Care. 1998;7(1):13–23.

35 Douglass GE, Daly M. Donor families experience of organ donation. Anaesth Intens Care. 1995;23(1):96–98.

36 Australasian Transplant Coordinators Association (ATCA). National donor family study: 2000 report. Melbourne: ATCA; 2000.

37 Randhawa G. Specialist nurse training programme: dealing with asking for organ donation. J Adv Nurs. 1998;28(2):405–408.

38 Dobb GJ, Weekes JW. Clinical confirmation of brain death. Anaesth Intens Care. 1995;23(1):37–43.

39 Coyle MA. Meeting the needs of the family: the role of the specialist nurse in the management of brain death. Intens Crit Care. 2000;16(1):45–50.

40 Pearson IY, Zurynski Y. A survey of personal and professional attitudes of intensivists to organ donation and transplantation. Anaesth Intens Care. 1995;23(1):68–74.

41 Haddow G. Donor and nondonor families’ accounts of communication and relations with healthcare professionals. Prog Transplant. 2004;14(1):41–48.

42 Sutton RB. Supporting the bereaved relative: reflections on the actor’s experience. Med Educ. 1998;32(6):622–629.

43 Redfern S. Organ donation … how do we ask the question? R Coll Nurs Aust Collegian. 1997;4(2):23–25.

44 Morton J, Blok GA, Reid C, Van Dalen J, Morley M. The European Donor Hospital Education Programme (EDHEP): enhancing communication skill with bereaved relatives. Anaesth Intens Care. 2000;28(2):184–190.

45 Verble M, Worth J. Adequate consent: its content in the donation discussion. J Transplant Coord. 1998;8(2):99–104.

46 Streat S, Silvester W. Organ donation in Australia and New Zealand – ICU perspectives. Crit Care Resusc. 2001;3(1):48–51.

47 Edwards L, Hasz R, Menendez J. Organ donors: your care is critical. RN. 1997;60(6):46–51.

48 Gortmaker SL, Beasley CL, Sheehy E, Lucas BA, Brigham LE, et al. Improving the request process to increase family consent for organ donation. J Transplant Coord. 1998;8(4):210–217.

49 Ehrle RN, Shafer TJ, Nelson KR. Referral, request and consent for organ donation: best practice – a blueprint for success. Crit Care Nurse. 1999;19(2):21–33.

50 Siminoff LA, Gordon N, Hewlett J, Arnold RM. Factors influencing families consent for donation of solid organs for transplantation. JAMA. 2001;286(1):71–77.

51 Holtkamp S. Wrapped in mourning: the gift of life and organ donor family trauma. New York: Brunner-Routledge; 2002.

52 Johnson C. The nurse’s role in organ donation from a brainstem dead patient: management of the family. Intens Crit Care Nurs. 1992;8(3):140–148.

53 Pelletier-Hibbert M. Coping strategies used by nurses to deal with the care of organ donors and their families. Heart Lung. 1998;27(4):230–237.

54 Duke J, Murphy B, Bell A. Nurses’ attitudes toward organ donation: an Australian perspective. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 1998;17(5):264–270.

55 Pearson A, Robertson-Malt S, Walsh K, Fitzgerald M. Intensive care nurses’ experiences of caring for brain dead organ donor patients. J Clin Nurs. 2001;10(1):132–139.

56 Kiberd MC, Kiberd BA. Nursing attitudes towards organ donation, retrievement, and transplantation. Heart Lung. 1992;21(2):106–111.

57 McCoy J, Argue PC. The role of critical care nurses in organ donation: a case study. Crit Care Nurse. 1999;19(2):48–52.

58 Australasian Transplant Coordinators Association. National Guidelines for organ and tissue donation, 4th edn. Sydney: ATCA; 2008.

59 . New Zealand Human Tissue Act 2008. Section 2. Available from www.moh.govt.nz/moh.nsf/indexmh/humantissue

60 Wheeler MS, O’Friel M, Cheung AHS. Cultural beliefs of Asian-Americans as barriers to organ donation. J Transplant Coord. 1994;4(3):146–150.

61 Thompson TL, Robinson JD, Kenny RW. Family conversations about organ donation. Prog Transplant. 2004;14(1):49–55.

62 Richter J, Eisemann MR. Attitudinal patterns determining decision-making in severely ill elderly patients: a cross-cultural comparison between nurses from Sweden and Germany. Int J Nurs Stud. 2001;38(4):381–388.

63 Bowman KW, Singer PA. Chinese seniors’ perspectives on end-of-life decisions. Soc Sci Med. 2001;53(4):455–464.

64 Verble M, Worth J. Cultural sensitivity in the donation discussion. Prog Transplant. 2003;13(1):33–37.

65 Scheinkestel CD, Tuxen DV, Cooper DJ, Butt W. Medical management of the (potential) organ donor. Anaesth Intens Care. 1995;23(1):51–59.

66 Lilly KT, Langley VL. The perioperative nurse and the organ donation experience. AORN J. 1999;69(4):779–791.

67 Regehr C, Kjerulf M, Popova S, Baker A. Trauma and tribulation: the experience and attitudes of operating room nurses working with organ donors. J Clin Nurs. 2004;13(4):430–437.

68 Holtkamp SC. The donor family experience: sudden loss, brain death, organ donation, grief and recovery. In: Chapman JR, Deierhoi M, Wight C. Organ and tissue donation for transplantation. London: Arnold; 1997:305–322.

69 Levvey B, Griffiths A, Snell G. Non-heart beating organ donors: a realistic opportunity to expand the donor pool. Transplant Nurses J. 2004;13(3):8–12.

70 Lewis J, Peltier J, Nelson H, Snyder W, Schneider K, et al. Development of the University of Wisconsin Donation after Cardiac Death evaluation tool. Prog Transplant. 2003;13(4):265–273.

71 Koostra G, Daemen J, Oomen A. Categories of non-heart-beating donors. Transplant Proc. 1995;27(5):2893–2894.

72 Brook NR, Waller JR, Nicholson ML. Nonheart-beating kidney donation: current practice and future developments. Kidney Int. 2003;63(4):1516–1529.

73 DeVita MA, Snyder JV, Arnold RM, Siminoff LA. Observations of withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment from patients who become non-heart-beating organ donors. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(6):1709–1712.

74 Ethics Committee, American College of Critical Care Medicine, Society of Critical Care Medicine. Recommendations for nonheartbeating organ donation. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(9):1826–1831.

75 Pearson J. Tissue Donation. Nurs Stand. 1999;13(45):14–15.

76 Australasian Transplant Coordinators Association. Confidential donor referral form. Sydney: ATCA; 2010.

77 Cordner S, Ireland L. Tissue banking. In: Chapman JR, Deierhoi M, Wight C. Organ and tissue donation for transplantation. London: Arnold; 1997:268–303.

78 Haire MC, Hinchliff JP. Donation of heart valve tissue: seeking consent and meeting the needs of donor families. Med J Aust. 1996;164(1):28–31.

79 Beard J, Ireland L, Davis N, Barr J. Tissue donation: what does it mean to families? Prog Transplant. 2002;12(1):42–48.

80 Michielsen P. Informed or presumed consent legislative models. In: Chapman JR, Deierhoi M, Wight C. Organ and tissue donation for transplantation. London: Arnold; 1997:344–360.

81 Kim T, Elliott D, Hyde C. Korean nurses’ perspectives of organ donation and transplantation: a review. Transplant Nurses J. 2002;11(3):20–24.

82 Abadie A, Gay S. The impact of presumed consent legislation on cadaveric organ donation: a cross country study. [Cited Jan 2005]. Available from http://ksghome.harvard.edu/~aabadie/pconsent, 2004.

83 Multi Organ Harvesting Aid Network (MOHAN). Foundation website. [Cited Jan 2005]. Available from www.mohanfoundation.org

84 Siminoff LA, Mercer MB, Arnold R. Families’ understanding of brain death. Prog Transplant. 2003;13(3):218–224.

85 NSW/ACT Organ Donation Network. Area donor coordinator clinical pathway 2004. Sydney: ODN; 2004.

86 New Zealand Ministry of Health. How to Become a Donor Fact Sheet 2008. [Cited Aug 2010]. Available from http://www.donor.co.nz/donor/donate/how_to.php

87 Australian Red Cross Blood Service. The role of Lifelinks’ organ donor coordinators. Sydney: ARCBS; 2004.

88 Moyes K. Improving organ donation rates with standard nucleic acid testing on all potential donors. Transplant Nurses J. 2002;11(1):15–16.

89 Rosendale JD, Kauffman HM, McBride MA, Chabalewski FL, Zaroff JG, et al. Aggressive pharmacologic donor management results in more transplanted organs. Transplantation. 2003;75(4):482–487.