18 Orbicularis oris, mentalis, depressor anguli oris

Summary and Key Features

• Aging of the perioral and chin regions is characterized by radial perioral rhytides (so-called smokers’ lines or lipstick lines), decrease in vermilion fullness, inversion of the vermilion, lengthened appearance of the cutaneous portion of the upper lip, downward turn of the oral commissures, pre-jowl notch or sulcus, and chin dimpling. Also, prominence of the labiomandibular (marionette lines), labiomental, and nasolabial folds occurs

• The goal of treatment of the lower face with botulinum toxin (BoNT) is to soften dynamic rhytides through muscular relaxation instead of completely paralyzing the target muscle

• The muscular anatomy of the lower face is complex; therefore caution is advised when performing BoNT injections

• BoNT can be used as monotherapy or as an adjunct to other procedures in lower face rejuvenation

• BoNT as monotherapy can be used for younger patients whose primary concern is not volume loss, but rather fine dynamic and / or static radial perioral rhytides due to muscular activity

• A combination treatment of BoNT and dermal fillers in the lower face has emerged as the gold standard for lower face rejuvenation

Introduction

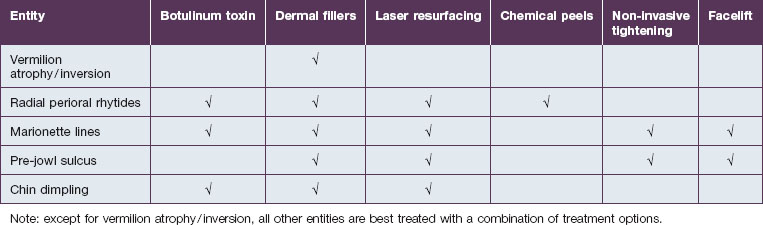

In the lower face, treatment strategies are traditionally focused on volume restoration; however, controlling hypermobility is also essential. Botulinum toxin is used as monotherapy or as an adjunct to other procedures in lower face rejuvenation. Treatment options include dermal fillers, chemical peels, laser resurfacing, non-invasive tightening modalities, and facelifts (with or without chin / pre-jowl implants) (Table 18.1). Although rhytidectomy can reduce the nasolabial and labiomandibular folds, this procedure cannot enhance the lip region owing to its anatomy. The perioral tissues include supportive ligaments that must be preserved, and there is a high risk of motor innervation injury affecting the perioral area through a facelift. This is due to the buccal and marginal mandibular branches of the facial nerve, which course superficially, ramify extensively, and are challenging to identify. Motor innervation injury leads to muscle weakness. A combination treatment with BoNT and fillers in the lower face has emerged as the gold standard because it addresses a broader spectrum of facial aging changes, without the need for surgery.

Anatomy

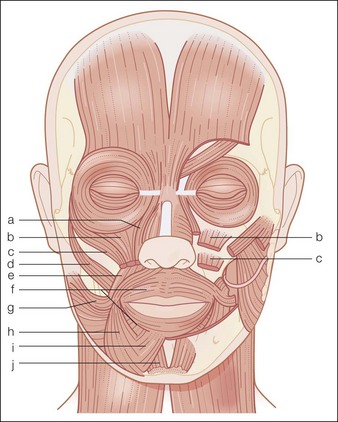

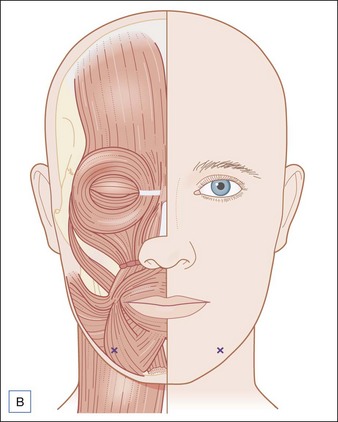

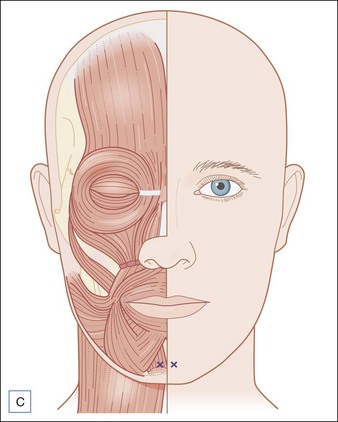

The musculature of the perioral and chin area is complex and includes the orbicularis oris, risorius, DAO, zygomaticus major, zygomaticus minor, levator anguli oris, levator labii superioris, levator labii superioris alaeque nasi (LLSAN), depressor labii inferioris, mentalis, and the platysma (Fig. 18.1).

Perioral and chin aging

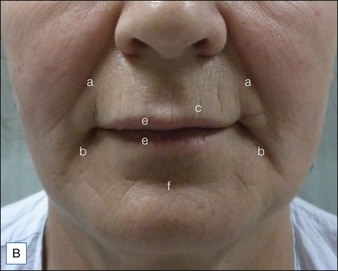

Aging of the perioral and chin regions is characterized by radial perioral rhytides (so called smokers’ lines or lipstick lines), decrease in vermilion fullness, inversion of the vermilion, downward turn of the oral commissures, lengthened appearance of the cutaneous portion of the upper lip, pre-jowl notch or sulcus, and chin dimpling. Additionally prominence of the labiomandibular (marionette lines), labiomental, and nasolabial folds can occur (Fig. 18.2A,B).

The labiomental fold is a horizontal fold located between the lower lip and the chin (see Fig. 18.2A,B). It is produced by the depressor anguli oris and the mandibular ligament. The nasolabial fold will be addressed in another chapter.

Rejuvenation

Patient selection for botulinum toxin perioral and chin rejuvenation

After understanding the patient’s wishes, the physician must choose which approaches are most effective and safe (see Table 18.1). For the lower face, usually a combination of approaches is necessary. Patients whose principal concern is not volume loss, but the end results of muscle hyperactivity, can benefit from BoNT as monotherapy (Table 18.2).

| Muscle target | Patient characteristics |

|---|---|

| Orbicularis oris | Radial perioral rhytides |

| Depressor anguli oris | Oral commissure turned downward without much volume loss |

| Mentalis | Dimpling chin |

Dosage and injection technique

When BoNT and fillers are used in the same session, the authors prefer to administer fillers first.

The amount of units below refers to Botox®.

Orbicularis oris

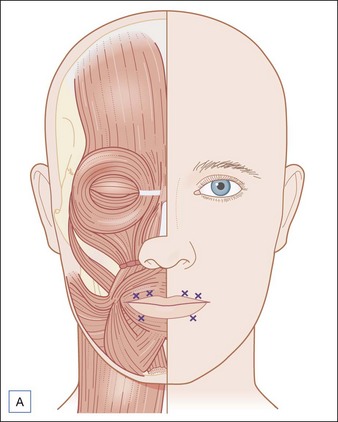

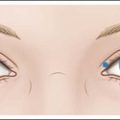

Injections are placed along or slightly above the vermilion border. Administration close to the vermilion border minimizes the spread of the toxin to the surrounding musculature (LLSAN and zygomaticus minor), thus reducing the risk of complications (Fig. 18.3A). Injections are superficial, just under the dermis.

Depressor anguli oris

The injections should be done laterally to the oral commissures to avoid injecting the depressor labii inferioris muscle, which can cause lip protrusion. Care must also be taken to avoid injecting so laterally that the buccinator muscle is affected. The anterior border of the buccinator muscle can be found by asking the patient to clench the teeth. The injection can be placed slightly anterior to this landmark (Fig. 18.3B).

Complications

Depressor anguli oris

Injections placed too medially can affect the depressor labii inferioris and cause flattening of the contour of the lower lip (Fig. 18.4). Injections placed too high may reach the orbicularis oris and result in problems with speech and suction. Additionally, flaccid cheeks, asymmetric smile, and lower lip weakness can occur.

Carruthers A, Carruthers J, Monheit GD, et al. Multicenter, randomized, parallel-group study of the safety and effectiveness of onabotulinumtoxinA and hyaluronic acid dermal fillers (24-mg/ml smooth, cohesive gel) alone and in combination for lower facial rejuvenation. Dermatologic Surgery. 2010;36:2121–2134.

Carruthers A, Carruthers J, Monheit GD, et al. Multicenter, randomized, parallel-group study of the safety and effectiveness of onabotulinumtoxinA and hyaluronic acid dermal fillers (24-mg/ml smooth, cohesive gel) alone and in combination for lower facial rejuvenation: Satisfaction and Patient-Report Outcomes. Dermatologic Surgery. 2010;36:2135–2154.

Carruthers JDA, Glogau RG, Blitzer A. Advances in facial rejuvenation: botulinum toxin type A, hyaluronic acid dermal fillers, and combination therapies – consensus recommendations. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2008;121(5S):S5–S30.

Fitzgerald R, Graivier MH, Kane M, et al. Update on facial aging. Aesthetic Surgery. 2010;30(suppl):S11–S24.

Gonzales-Ulloa M, Flores ES. Senility of the face: basic study to understand its causes and effects. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 1965;36:239–246.

Le Louarn C, Buthiau D, Buis J. Structural aging: the facial recurve concept. Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. 2007;31(3):213–218.

Semchyshyn N, Sengelmann RD. Botulinum toxin A treatment of perioral rhytides. Dermatologic Surgery. 2003;29(5):490–495.

Vleggaar D, Fitzgerald R. Dermatological implications of skeletal aging: a focus on supraperiosteal volumization for perioral rejuvenation. Journal of Drugs in Dermatology. 2008;7(3):209–220.