Oral Medicine

Perspective and Principles of Disease

Musculoskeletal Unit

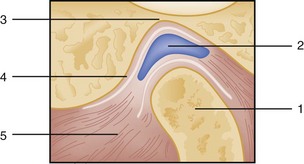

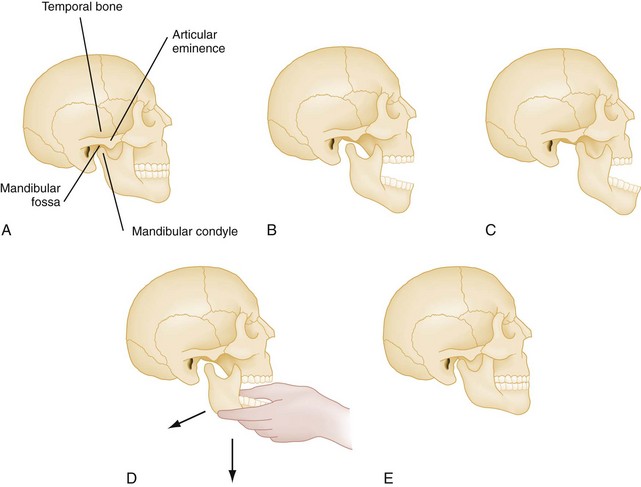

The mandible is formed by two rami that divide into a horizontal and an ascending portion. The horizontal portion forms the body of the mandible. The ascending ramus divides into the coronoid process anteriorly and the condylar process posteriorly. The temporomandibular articulation is unique because it consists of a bilateral joint, or diarthrosis, between the mandibular fossa and articular eminence of the mandible’s temporal bone and condyle (Fig. 70-1). An intervening layer of fibrous connective tissue separates the articulating surfaces. A fibrous capsule also surrounds the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) and is reinforced by capsular ligaments that help limit mandibular range of motion. Functionally, when the mandible opens, the condyles move inferiorly and anteriorly down the eminence; during closure, the mandible moves posteriorly along the eminence and superiorly into the fossa.

Teeth

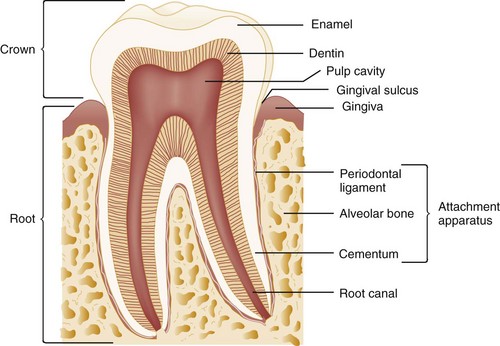

The pulp is the tooth’s center and serves as its neurovascular supply. The primary purpose of the pulp is to provide sensation and to produce dentin, a microtubular structure that hydrates and cushions the tooth during mastication. The part of the tooth normally visible in the oral cavity is the coronal portion covered with enamel, the hardest substance in the body. The part that is not normally visible and anchors the tooth is called the root. The root is covered with cementum, which is much softer than enamel and not designed for exposure in the oral cavity (Fig. 70-2).

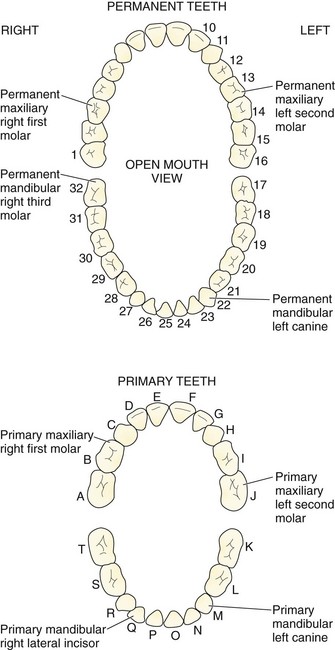

The normal primary, or deciduous, dentition consists of 10 mandibular and 10 maxillary teeth. The primary dentition is important for mastication, cosmesis, and growth and development and functions as a physiologic space maintainer. Starting at the midline and moving posteriorly in any quadrant, the normal dentition consists of a central incisor, lateral incisor, canine, and two primary molars. The lower central incisor is the first tooth to erupt, at approximately 6 months of age; all primary teeth should be present by 3 years of age. If not, further investigation for developmental or endocrine abnormalities is warranted. The permanent dentition begins to erupt at approximately 5 to 6 years of age with the appearance of the first molar. Normally, the permanent dentition consists of 32 teeth: the central incisor, lateral incisor, canine, two premolars, and three molars. The third molars are the last to erupt, appearing at approximately 16 to 18 years of age, and are commonly called “wisdom teeth.” The primary molars are replaced by the permanent premolars. There are many numbering systems for teeth, but none are universal. Perhaps the most common system for the permanent dentition consists of numbering the teeth from 1 to 32, starting with the upper right third molar (1) and moving to the upper left third molar (16), to the lower left third molar (17), and to the lower right third molar (32). The starting point for this numbering system can be recalled by the mnemonic “upright.” Because there may be congenital absence of teeth or additional, supernumerary teeth, it is perhaps best for practitioners to describe anatomically which tooth is involved—for example, the upper left second premolar or the lower right second molar (Fig. 70-3).

Periodontium

The periodontium consists of the gingival unit and the attachment apparatus. The gingiva is covered with keratinized, stratified, squamous epithelium and invests the tooth and alveolar bone. Apical to the gingiva is the alveolar mucosa, which is covered by nonkeratinized epithelium and is more subject to trauma. In healthy individuals the gingiva is attached firmly to the tooth by connective tissue fibers inserting into the cementum, extending coronally from the alveolar bone to the cementoenamel junction. A 2- to 3-mm cuff of tissue, the gingival sulcus, is bordered by the enamel surface of the tooth, the gingival epithelium, and the junctional epithelium at its base (see Fig. 70-2). In a disease state, such as in the presence of the loss of alveolar bone, this cuff increases in depth and is called a “pocket.”

Fascial Planes of the Head and Neck

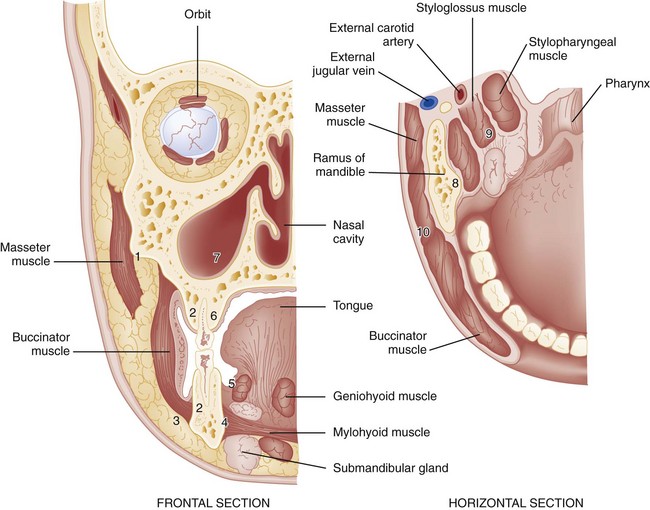

The fascial planes of the head and neck are defined as potential spaces filled with loose areolar tissue that separates the layers of fascia of the head and neck. The deep cervical fascia is most important in a discussion of the extension of oral infection to the head and neck (Fig. 70-4). The deep cervical fascia consists of the superficial and investing layer, the pretracheal layer, the prevertebral layer, and the carotid sheath. The superficial and investing layer surrounds the entire neck; it splits as it attaches to the inferior border of the internal pterygoid muscles at the mandible’s ascending ramus. This split forms the masticator space. This space communicates superiorly above the level of the zygomatic arch with the superficial and deep temporal pouches.

Pathophysiology

Nontraumatic Dental Emergencies

Two pathophysiologic processes affect the dental health of most of the population: (1) dental caries and (2) periodontal disease. Variables related to both disease states include the oral environment, consisting of the teeth and attachment apparatus; the presence of local factors such as bacterial plaque, oral microflora, and substrate; and host states, including immunocompromising diseases and nutritional status. Factors such as water fluoridation, fluoride supplements, and plaque control techniques (e.g., flossing, brushing, orthodontic and dental surgical procedures) have significantly decreased the prevalence of dental caries and periodontal disease. However, the emergency department (ED) is the frequent source of care for dental emergencies, with toothache related to dental caries being the most common complaint. This occurs because of both lack of after-hours access for dental complaints and socioeconomic factors (self-pay and Medicaid). A recent study from Kansas City shows an increased volume from 2001 to 2006 from 13.1% up to 19%.1

Pus leaks from the apex of the root and forms an abscess; this is termed a periapical abscess. Periapical abscesses are confined within the alveolar bone (Fig. 70-5). The abscess may break through the cortical plate of either the mandible or the maxilla and spread subperiosteally. Subperiosteal extensions are generally well confined anatomically by muscle attachments; however, if the muscle attachments are violated, either during a surgical procedure or by the natural extension of an infective process, the bacteria can gain access to the fascial planes of the head and neck. Infection extending to the submaxillary, sublingual, and submental spaces with elevation of the tongue is called Ludwig‘s angina. Ludwig’s angina is one of the most serious mandibular infections because of its potential for airway obstruction.

Clinical Features

Examination of the Oral Cavity

The examiner should wear eye protection, a mask, and gloves in compliance with universal precautions when examining the oral cavity. Ideally the patient should be placed in a dental or ear, nose, and throat chair or on a cart at a 45-degree angle. Because pediatric patients are unlikely to cooperate with the examination, the following technique is used by some experienced practitioners. The child sits in the parent’s lap, or the child is first placed in the parent’s lap facing the parent. The examiner then sits in front of the parent. While the parent gently restrains the child’s arms and legs, the emergency physician can lean the child backward and lock the child’s head between the physician’s legs.2

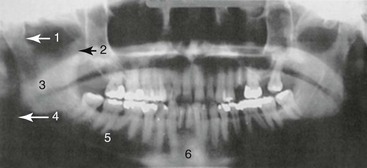

Radiographic evaluation of teeth is best accomplished with dental (periapical) films. These films are generally not available in the ED, however. A panoramic radiograph is a useful alternative (see Fig. 70-5).

Diagnostic Imaging

Radiographic evaluation of teeth is ideally accomplished using dental (periapical) films, but these films are generally not available in the ED. More commonly, the panoramic radiograph is a useful alternative if imaging is felt to be required (see Fig. 70-5). The diagnosis and treatment of a dental abscess, for example, can be determined on the basis of clinical examination alone. A recent study compared the use of ED bedside ultrasound with the use of a panoramic radiograph. The sensitivity and specificity of the ultrasound were 92% and 100%, respectively. The advantage of the ultrasound is the lack of ionizing radiation; in addition, it assists in the determination of the presence of pus for incision and drainage.3 Computed tomography (CT) is used primarily when there is concern for deep space abscesses.

Dental Caries

Treatment

Palliative management is indicated for most odontalgia. Systemic analgesics, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or synthetic opioid agents, are indicated. In a meta-analysis of 11 studies comparing flurbiprofen, 65 to 70% of patients experienced 50% pain relief compared with 25 to 30% with placebo; this was similar to findings with comparable NSAIDs, and patients had similar need for rescue pain control at 6 hours.4 Although NSAIDs should be sufficient for most pain resulting from carious teeth, a therapeutic dental block may offer immediate relief. Synthetic opioids also are useful and are indicated in some cases but are generally not recommended in chronically carious teeth without an acute process.5 A limited quantity of analgesics should be dispensed, which encourages follow-up with a general dentist.

Simple Dental Abscess

Treatment

Standard practice for years included starting the patient on phenoxymethylpenicillin (penicillin V) 250 mg four times daily or doxycycline 100 mg bid for 10 days and warm saline rinses and referring him or her to an oral maxillofacial surgeon or general dentist. Drains are removed in 24 to 48 hours, and antibiotics are continued for 7 to 10 days.5 However, recent reviews have questioned the need for routine prescribing of antibiotics if sufficient drainage of pus has been achieved.6,7

Spread of Infection to the Head and Neck

The presence of cellulitis or swelling in the contiguous spaces of the head and neck indicates the spread of a localized infection. In the early stages of such an infection, the upper half of the face is generally involved, with extension of infection from maxillary teeth; cellulitis from mandibular teeth generally involves extension to the lower half of the face and the neck (Fig. 70-6). More advanced infections may extend into any of the fascial planes of the head and neck down to the mediastinum. In the nondebilitated host, untreated dental infections tend to localize and drain spontaneously and extraorally. In the presence of a compromised host or aggressive microorganisms, spread into the fascial planes is more common, with a potential for greater morbidity and mortality. General indications for admission include suggested spread of infection to fascial planes, high fever, toxic appearance, trismus, and an immunocompromised host.

The potential sequelae of sepsis and airway obstruction must be appreciated. CT of the head and neck can be useful if the diagnosis is in doubt. Airway management should be undertaken when indicated, particularly if signs or symptoms of impending airway obstruction are present or developing (altered voice, drooling, stridor). The intubation should be approached as a difficult airway, as outlined in Chapter 1. An ear, nose, and throat specialist or oral maxillofacial surgeon should be consulted for ongoing management, including determination of the site of the initial focus so that pus can be evacuated.

Fever is common as with any infection. Any irritation of the internal pterygoid or masseter muscles results in trismus. Trismus is the inability to open the mouth because of involuntary muscle spasm. Trismus limits visualization of the pharynx and may make diagnosis of lateral or retropharyngeal space involvement difficult. Trismus is muscular in origin, not a result of impaired or augmented neuromuscular transmission, and so is often minimally improved or not improved at all after administration of a neuromuscular blocking agent (e.g., succinylcholine) for intubation, especially if the trismus is caused by localized swelling (vs. pain and spasm). Intubation in all patients with trismus is presumed to be difficult. Preparations should be made to perform a fiberoptic intubation or to establish a surgical airway.8 Difficulty swallowing or handling secretions suggests the possibility of retropharyngeal or parapharyngeal infection. Respiratory distress may be apparent, or the airway may occlude rapidly after a period of minimal signs of impending obstruction.

Spread of mandibular dental infection frequently results in a cellulitis called Ludwig’s angina, a bilateral, boardlike swelling involving the submandibular, submental, and sublingual spaces with elevation of the tongue. The most serious immediate sequela is airway obstruction. A characteristic brawny induration is present; there is no fluctuance for incision and drainage. Hemolytic Streptococcus is most commonly responsible for the infection, although a mixed staphylococcal-streptococcal flora is common, and both may lead to an overgrowth of anaerobic gas-producing organisms, including Bacteroides fragilis. Treatment consists of antibiotics and airway management. Although oral intubation can be attempted, an “awake” technique is recommended (see Chapter 1) because inability to displace the tongue into the submandibular space with a laryngoscope may make oral intubation impossible; fiberoptic nasopharyngoscopy is an option progressing to cricothyrotomy. In a study of 10 cases of Ludwig’s angina requiring surgical decompression, after inhalational anesthesia, the vocal cords were visualized in 9 of the 10 patients. One patient required tracheostomy.

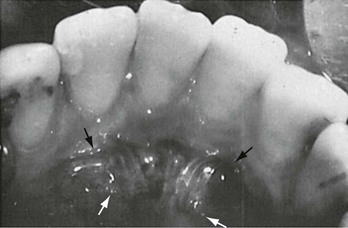

Acute Necrotizing Ulcerative Gingivitis

In contrast to gingivitis, in which the gingiva becomes inflamed in response to an irritant such as bacterial plaque but is not invaded by bacteria, acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis (ANUG) is a periodontal lesion in which bacteria actually invade non-necrotic tissue. ANUG lesions commonly are accompanied by systemic manifestations of fever, malaise, and regional lymphadenopathy. ANUG is characterized by painful edematous interdental papillae. The normally pointed interdental papillae are blunted and ulcerated. A gray pseudomembrane covers the tissue and leaves a bleeding surface when removed. The lesions can involve any part of the gingiva but are more common in the anterior incisor and posterior molar regions. The patient develops pain, a metallic taste, and foul breath (Fig. 70-7).

Oral Pain

Root Canal Pain

Endodontic or root canal therapy involves opening the pulp chamber of the tooth, removing pulp tissue from the chamber and the root portion of the tooth to the apex, irrigating and effectively sterilizing the canal, and sealing the pulp chamber to prevent ingress of saliva and contamination. After surgery the patient may experience exquisite pain caused by irritation beyond the apex of the tooth from instrumentation or from the buildup of gas from the irrigation solutions. Swelling may cause the tooth to be elevated slightly out of the socket so that premature contact during chewing causes extreme pain. These patients may have no relief with either systemic analgesics or anesthetic nerve blocks, presumably because of the sensation of intense pressure.9 Treatment may consist of opening the canal to allow the gas or fluid to escape and of occlusal adjustment to take the tooth out of contact; the patient’s general dentist or endodontist may have to be contacted.

Maxillary Sinusitis

Dental pain often is referred to the area of the sinuses; similarly, congested or inflamed sinuses in the proximity of the apices of the maxillary teeth may cause apparent odontogenic pain. The patient may report throbbing pain unrelated to changes in temperature. On examination, there is no apparent dental cause. There may be tenderness over the maxillary sinuses or periorbital regions. Nasal discharge may be present. The panorex film can screen for dental and sinus pathology, although a CT scan would show sinus pathology more clearly.10

Postextraction Pain

Pain after an extraction (i.e., immediate periosteitis) is common for approximately 24 hours. Systemic analgesics are usually adequate for pain control. NSAIDs (e.g., ibuprofen 600 mg q6h) are effective analgesics and are commonly prescribed.11

A much more painful condition, acute alveolar osteitis or dry socket, may occur approximately 3 to 4 days after an extraction. The patient has a pain-free interval followed by sudden onset of excruciating pain associated with a foul odor. The pathophysiology involves premature loss of the healing blood clot from the socket, with a localized infection and inflammation of the of the bone.12

Treatment of a dry socket consists of an anesthetic nerve block, gentle irrigation of the socket, and packing of the socket with iodoform gauze saturated with a medicated dental paste, such as Sed-A-Dent, or barely dampened with eugenol (oil of cloves). The packing affords almost immediate relief, although it is recognized to delay natural wound healing.12 Patients with a dry socket require daily follow-up for pack changes until sufficient natural wound healing has occurred. Most dentists include oral antibiotic (e.g., penicillin, clindamycin, or doxycycline) coverage, analgesics, and NSAIDs with this regimen until the condition resolves. However, there is no evidence to support this as a routine practice, and the use of antibiotics postoperatively after third molar tooth extraction is controversial.

Paroxysmal Pain of Neuropathic Origin

Paroxysmal pain of neuropathic origin is most commonly caused by tic douloureux, or trigeminal neuralgia. The diagnosis is made principally on the basis of history. The patient reports paroxysmal episodes of an excruciating, lancinating pain, also described as recurrent bursts of an electric shock. The pain follows the anatomic distribution of the involved division of the fifth cranial nerve. On physical examination the pain sometimes can be elicited by tapping specific areas of the face (the so-called “trigger zones”) in the region of the distribution of the nerve involved. Medical management for tic douloureux consists of carbamazepine, starting at 100 mg bid, although some patients may be afforded no relief.13 In a study of 61 patients, a positive response to carbamazepine in the presence of a distinct trigger zone was a strong indicator of trigeminal neuralgia.14

Other causes of orofacial pain of the paroxysmal type include headaches (see Chapter 16). Vascular headaches, such as migraine and cluster headaches, may have facial pain as their principal manifestation. Rheumatologic disorders, such as giant cell arteritis and polymyalgia rheumatica in the elderly, can result in facial pain. Dull pain in the lower jaw is not always of dental origin. Myocardial ischemia may cause isolated jaw pain.

Temporomandibular Myofascial Pain Dysfunction Syndrome

The TMJ is a bilateral joint subject to almost continuous use. It is extremely sensitive to proprioceptive stimuli and can react to interferences in occlusion of only fractions of a millimeter. TMJ syndrome results from anatomic disharmony (see Fig. 70-1) and occlusal disturbances. The condition is aggravated by trauma, clenching of the teeth, or bruxism. Patients report pain in the region of the TMJ, usually unilateral. The pain is dull, worsens during the course of a day, and, in extreme cases, may result in trismus with palpable masseter and internal pterygoid spasm.15

TMJ radiographs are not helpful. Treatment consists of the external application of heat for 15 minutes four to six times per day, soft diet, analgesics including NSAIDs, and a muscle relaxant, such as diazepam 2 to 10 mg up to four times per day.16 Patients should be referred to a dentist specializing in TMJ disorders, such as a periodontist or a periodontal prosthodontist. Insufficient evidence exists for or against the current treatment at this stage, which consists of continued physiotherapy, bite appliances that put the musculature at rest, and occlusal adjustment.17,18 Although certain anatomic abnormalities are amenable to surgical correction, most oral maxillofacial surgeons consider surgery only for the most intractable cases.19

Pericoronitis

Pain from the eruption of the third molar teeth (i.e., wisdom teeth) in an adult is common. Trapped food and plaque cause the gingiva surrounding crowded, malerupted, or impacted third molar teeth to become inflamed and swollen. This condition is called pericoronitis and is extremely painful because of repeated trauma from the opposing third molar biting on tender tissues and from distention of retromolar tissue on opening of the mandible. Pericoronitis is treated locally with warm saline irrigation, with or without hydrogen peroxide rinses. The microbiology of pericoronitis is similar to that of other dentoalveolar infection and periodontitis. Antibiotics that are effective against viridans streptococci and oral anaerobes are prescribed.20 Common options include penicillin VK 250 mg four times per day, doxycycline 100 mg bid for 10 days, or metronidazole for its anaerobic coverage. If fluctuant pus is present, incision and drainage should be performed, with care taken not to track the infection posteriorly or to dissect deeply into distorted tissues, possibly encountering the internal carotid artery. Definitive treatment involves removal of the opposing third molar tooth for immediate relief and removal of the involved third molar tooth after the infection is resolved. These patients should be referred to an oral maxillofacial surgeon.

Aphthous Stomatitis

Patients may report recurrent small oral mucosal ulcers. The ulcers are approximately 2 to 3 mm in size with a white center. The lesions tend to be tender but rarely become infected. Multiple ulcers that have coalesced can create an impressively large lesion. One third of the population may be affected by this condition, which is believed to be related to stress, nutrition, oral trauma, and hormonal causes. The condition is self-limiting, and treatment is symptomatic. There are numerous over-the-counter preparations that help with symptoms (hydrogen peroxide rinse; topical dental preparations such as benzocaine and an emollient gel; 50 : 50 mixture of diphenhydramine [Benadryl]; and Kaopectate or Maalox).21 Prescription regimens, such as steroid-antibiotic ointment (Kenalog in Orabase) or sucralfate are also useful. A topical sulfuric acid phenolic, Debacterol, available only by prescription, is applied to the ulcer and appears to seal the ulcer and promote rapid healing. Ulcers that may appear similar to aphthous ulcers are those on the soft palate associated with hand-foot-and-mouth disease or lesions on the gingivae and tongue from herpetic stomatitis.22

Oral Manifestations of Systemic Disease

Collagen Vascular Diseases

Systemic lupus erythematosus is the most common collagen vascular disease to have oral manifestations. Patients commonly have large ulcerated intraoral lesions with necrotic borders. The lesions are usually secondarily infected and painful (Fig. 70-8).

Drug-Induced Gingival Hyperplasias

Some degree of gingival hyperplasia is present in 40% of patients undergoing long-term phenytoin therapy. Younger patients seem to be affected more often than older patients. The degree of gingival hyperplasia does not seem to be related to dosage. The disease ranges from slight enlargements of the interdental papillae to massive enlargement of the gingiva, which covers the crowns of the teeth and may move the teeth. The risk of gingival hyperplasia has been shown to be two times higher in users of calcium channel blockers.23 The hyperplastic tissue is subject to infection. The presence of local irritants seems to make the hyperplasia worse. Treatment of the condition includes removal of local irritants and surgical excision of the hyperplastic tissue; therefore referral to a periodontist is appropriate. If the causative agent is not discontinued, hyperplasia is likely to recur, although less severely if good oral hygiene is maintained.

Traumatic Dental Emergencies

The anterior teeth are commonly injured from falls or direct blows to the teeth. Forceful blows to the mandible directed superiorly may result in fractures of the premolars and molars caused by a wedgelike effect of the cusps of the mandibular teeth in the central fossae of the maxillary teeth. Many children have an anterior overbite, which makes this part of the dentition more prone to injury. Blunt trauma to the dentition may result in damage to the neurovascular supply to the tooth, bleeding within the tooth, fractures of the root or crown, loosening of the tooth, or actual expulsion of the tooth from its socket. A long-term sequela of blunt trauma or reimplantation of teeth is resorption of the root.24 Fractures of the anterior teeth are managed based on the type of fracture, its relation to the pulp of the tooth, and the patient’s age. Table 70-1 describes the classification of trauma to the teeth.

Table 70-1

Classification of Tooth Fractures

Adapted from Fuks AB, Camp J: Crown fractures: A practical approach for the clinician. Chapter 3 in Berman LH, Cohen S, Blanco L: A Clinical Guide to Dental Traumatology. St Louis, Mosby, 2007:4-5.

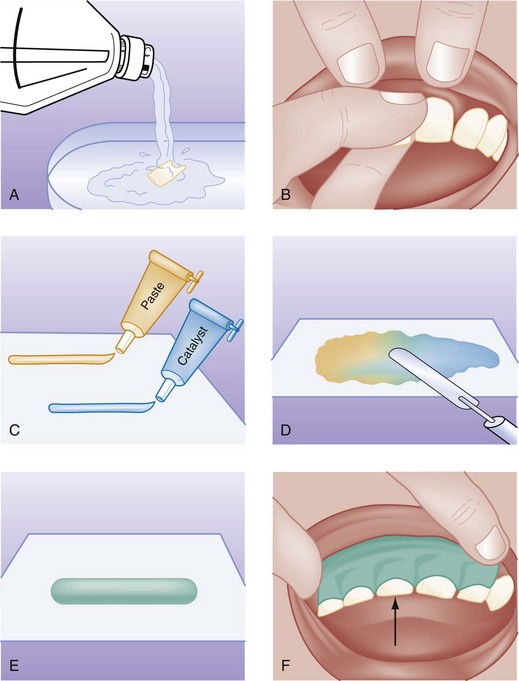

Subluxed and Avulsed Teeth

As a temporizing measure, the patient can bite gently on a piece of gauze, or the teeth can be stabilized for 24 to 48 hours with the application of a periodontal pack (e.g., Coe-Pak). A resin and catalyst paste are mixed together in equal quantities to a firm consistency and molded over the anterior and posterior aspects of the involved tooth and two or three adjacent teeth on each side. The patient is asked to close the mouth while the mixture hardens (Fig. 70-9). The patient is advised to avoid hot liquids, which would soften the pack; eat a liquid to soft diet; and see a dentist as soon as possible.

Avulsed teeth are completely torn from the socket and are a true dental emergency. If teeth are unaccounted for, the possibility of aspiration or entrapment in soft tissues should be considered. Management of recovered avulsed teeth depends on the age of the patient and the length of time for which the tooth has been absent from the oral cavity.25 Avulsed primary teeth in a pediatric patient age 6 months to 6 years are not replaced in the socket. Reimplanted primary teeth ankylose or fuse to the bone, so although the dentofacial complex grows downward and forward, the reimplantation site does not. There also may be interference with the eruption of the permanent tooth. Cosmetic deformity results in either case.26 Such patients should be referred to a pedodontist for consideration of a space maintainer or cosmetic appliance.

The worst situation is to allow the tooth to be transported in a dry medium. Storage in plain water is not much better. Although saliva is a reasonable storage medium, milk is preferable because of its osmolarity and essential ion concentration of Ca2+ and Mg2+.27 The best storage and transport medium is Hank’s solution, a balanced pH cell culture medium. This solution is commercially available as the Save-a-Tooth system (3M). Hank’s solution can maintain the viability of the cells for 12 to 24 hours or more.27 If the tooth has been avulsed for more than 30 minutes or has been allowed to dry, placement of the tooth in Hank’s solution helps restore the periodontal ligament cells. With the Save-a-Tooth system, the tooth is simply dropped into the basket and the lid replaced. For removal, the lid is removed, the basket is lifted out of the solution, and the tooth is retrieved by tipping the basket over onto the padded lid.

When the patient arrives in the ED, the tooth should be reimplanted at the earliest opportunity. If this cannot be done, the tooth can be placed in Hank’s solution or a Save-a-Tooth system (especially if avulsion occurred more than 30 minutes previously or if the patient has other life threats that are being managed). A recent study demonstrated that simple oral rehydration solution is as effective as Hanks solution for this purpose and may be more readily available in an ED.28 If Hank’s solution or oral rehydration solution is not available, the tooth is rinsed with saline, the socket is suctioned if necessary, and the tooth is immediately implanted. Local anesthesia may be necessary. The tooth should be manipulated only by the crown, if possible, so that the remaining periodontal ligament fibers are not damaged. Stabilization must be performed immediately, or the tooth will exfoliate. Stabilization is performed as described for markedly subluxated teeth (see Fig. 70-9). Other methods of stabilization with use of light-cured bonding resins are possible and, in a recent study, have been shown to be very satisfactory for the emergency physician if he or she has been trained to use them.29 The status of tetanus immunization should be checked, and the patient should be treated according to the standard for a non–tetanus-prone wound (i.e., 10-year immunization update). Although there is inconclusive evidence to support the practice, dentists typically place patients on phenoxymethylpenicillin (penicillin VK) 250 mg four times a day or doxycycline 100 mg bid in an effort to increase the likelihood of periodontal ligament healing.30

The patient is placed on a liquid diet for several days and advanced to a soft diet for 1 week. Stabilization is maintained for approximately 2 weeks, and the tooth is gradually brought into function to prevent ankylosis. Teeth that have been avulsed for longer than 30 minutes invariably require endodontic therapy owing to loss of pulp viability.26,31 Although there may be concern about the anatomic orientation of the tooth or more confusion about which socket to use when several teeth are avulsed, each tooth should be placed into a socket with the best fit so that the tooth remains in a good physiologic environment. The dentist can make any necessary readjustments before final stabilization.

Alveolar Bone Fractures

Dental fractures and subluxated or avulsed teeth may be associated with fractures of the alveolus. Alveolar fractures may be apparent clinically from exposed pieces of bone or diagnosed radiographically. In massive facial trauma, care should be taken to conserve as much of the alveolar bone as possible, unless there is a great danger of aspiration. Indiscriminate loss of alveolar bone results in tremendous cosmetic deformity that is difficult to restore with prosthetic devices or leaves no foundation for a dental implant, thus necessitating autologous bone grafting procedures.32

Soft Tissue Injuries

Gaping intraoral lacerations tend to become ulcerated, secondarily infected, and painful. Fibrotic healing results in a cumbersome scar that is subject to repeated trauma during chewing. A well-prepared mucosal wound is closed with No. 4-0 absorbable suture. Chromic gut has the advantage of dissolving more rapidly in the oral cavity; some physicians prefer polyglactin 910 (Vicryl) owing to its softer nature for both handling and patient comfort.33 Gingival and tongue lacerations are best closed with an absorbable polyglactin or nonabsorbable suture or black silk (4-0 or 5-0) because these materials are less irritating to the touch. Absorbable suture is preferred for children. Large tongue lacerations, especially if the border is involved, should be well approximated or a cleft will form during healing, necessitating a revision. Anesthesia can be achieved by either direct local injection or lingual block. Small (<1 cm) lacerations are best left alone, especially in children. Even larger tongue lacerations can be left alone in children if there is no chance of a resulting cleft deformity.34 The management of through-and-through lacerations involving skin and oral mucosa is controversial. With proper preparation, mucosa can be closed as described previously. Subcutaneous sutures (absorbable) are placed to close the subcutaneous tissues from the outside, removing tension from the skin. Skin is closed with No. 6-0 or No. 7-0 synthetic nonabsorbable sutures that are removed in 3 to 4 days, depending on the amount of muscle tension on the wound. Intraoral silk closures are removed in approximately 7 days. There has been no well-designed prospective randomized trial to evaluate the benefit of prophylactic antibiotics after intraoral laceration repair. Some studies show, at best, a potential trend in benefit for through-and-through lacerations. Simple lacerations do not seem to benefit, and wounds that are over 24 hours old become universally infected. Therefore at this time the use of prophylactic antibiotic coverage is based on clinical judgment.35 Typically, if antibiotics are prescribed for prophylaxis, choices would include penicillin 250 mg four times a day or doxycycline 100 mg bid for 10 days. The patient is advised to maintain oral hygiene, use saline rinses six times a day, place a triple-antibiotic ointment over the skin closure, and watch carefully for infection. These patients should be seen in 48 to 72 hours to check for infection. Normal postoperative soft tissue swelling should not be mistaken for an infected wound.

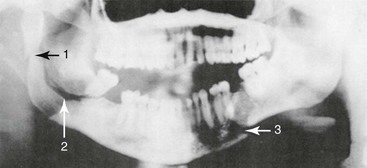

Temporomandibular Joint Dislocation

The mandibular condyles may dislocate from trauma, but more often, dislocation follows extreme opening of the mandible such as occurs after a yawn or laughter. TMJ dislocation occurs when the condyle travels anteriorly along the eminence and becomes locked in the anterosuperior aspect of the eminence. The masseter, internal pterygoid, and temporalis go into spasm attempting to close the mandible; trismus results, and the condyle cannot return to the temporal fossa. Mandibular dislocation is painful and frightening for the patient. Patients prone to mandibular dislocation include individuals with anatomic disharmonies between the fossa and articular eminence, weakness of the capsule and the temporomandibular ligaments, or torn ligaments. Dystonic reaction to drugs may result in mandibular dislocation. Patients who have had one episode of mandibular dislocation are predisposed to further dislocations. If a unilateral dislocation has occurred, the jaw deviates to the opposite side. More commonly, a symmetrical dislocation occurs. In cases of traumatic dislocation, a panorex or CT scan of the facial bones should be taken to exclude the possibility of a fracture (Figs. 70-10 and 70-11).

Reduction of a dislocated mandible is straightforward, although often difficult because the strength of the masseter contraction must be overcome. The patient requires procedural analgesia and sedation as for any other dislocation. Either facing the patient or from behind, the emergency physician grasps the mandible with both hands; the thumbs rest on the ridge of the mandible intraorally, posterior to the molars, and the fingers wrap around the outside of the jaw. It is best to have the patient sitting up, with a firm surface behind the head, so that posterior and inferior pressure can be exerted without accompanying movement of the patient’s entire head. Some physicians prefer to place the thumbs on the occlusal surfaces of the teeth; in this case the thumbs are wrapped with gauze to protect them when reduction is accomplished because the masseter muscles can contract with tremendous force. Firm, progressive, downward pressure is applied on the mandible to free the condyles from the anterior aspect of the eminence; the mandible is guided caudally, then posteriorly and superiorly back into the temporal fossae (Fig. 70-12). If this maneuver is unsuccessful, both hands can be used on the affected side of the mandible, with reported success.36 The patient is advised to avoid extreme opening of the mandible such as occurs during laughing and yawning, to begin a soft diet for 1 week, and to apply warm compresses in the TMJ area. NSAIDs and muscle relaxants may be helpful. Patients with chronic dislocation may be helped initially with the application of a Barton bandage (elastic fabricated bandage that wraps around the top of the head and mandible). Intermaxillary fixation with wire and elastics may be necessary. Patients who have difficulty reducing the dislocation by themselves or who experience frequent recurrences may require surgical revision of the eminence for relief.

References

1. Hong, I, et al. Secular trends in hospital emergency department visits for dental care in Kansas City, Missouri, 2001-2006. Public Health Rep. 2011;126:210–219.

2. Peretz, G, Gluck, GM. The use of restraint in the treatment of paediatric dental patients: Old and new insights. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2002;12:392–397.

3. Adhikari, S, Blaivas, M, Lander, L. Comparison of bedside ultrasound and panorex radiography in the diagnosis of a dental abscess in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2011;29:790–795.

4. Sultan, A, McQuay, HJ, Moore, RA, Derry, S. Single dose oral flurbiprofen for acute postoperative pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;3:CD007358.

5. Rodriguez, DS, Sarlani, E. Decision making for the patient who presents with acute dental pain. AACN Clin Issues. 2005;16:359–372.

6. Ellison, SJ. The role of phenoxymethylpenicillin, amoxicillin, metronidazole, and clindamycin in the management of acute dentoalveolar abscesses—a review. Br Dent J. 2009;206:357–362.

7. Pantlin, L. Is there a role for antibiotics in periodontal treatment? Dent Update. 2008;35:493–496.

8. Howaldt, HP, Kessler, P. Fiberoptic intubation as a safe method for the treatment of odontogenic abscesses. Dtsch Zahnarztl Z. 1992;47:46–47.

9. Klasser, DG, Kugelmann, AM, Villines, D, Johnson, BR. The prevalence of persistent pain after nonsurgical root canal treatment. Quintessence Int. 2011;42:259–269.

10. Hansen, JG, Lund, E. The association between paranasal computerized tomography scans and symptoms and signs in a general practice population with acute maxillary sinusitis. APMIS. 2011;1119:44–48.

11. Barden, J, Edwards, JE, McQuay, HJ, Wiffen, PJ, Moore, RA. Relative efficacy of oral analgesics after third molar extraction. Br Dent J. 2004;197:407–411.

12. Kolokythas, A, Olech, E, Miloro, M. Alveolar osteitis: A comprehensive review of concepts and controversies. Int J Dent. 2010;2010:249073.

13. Jorns, TP, Zakrewska, JM. Evidence-based approach to the medical management of trigeminal neuralgia. Br J Neurosurg. 2007;21:253–261.

14. Sato, J, et al. Diagnostic significance of carbamazepine and trigger zones in trigeminal neuralgia. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Oral Endod. 2004;97:544.

15. Reneker, J, Paz, J, Petrosino, C, Cook, CE. Diagnostic accuracy of clinical tests and signs of temporomandibular joint disorders: A systematic review of the literature. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2011;41:408–416.

16. Martins-Júnior, RL, Palma, AJ, Marquardt, EJ, Gondin, TM, Kerber Fde, C. Temporomandibular disorders: A report of 124 patients. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2010;11:071–078.

17. Al-Ani, MZ, Davies, SJ, Gray, RJM, Sloan, P, Glenny, AM. Stabilisation splint therapy for temporomandibular pain dysfunction syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;1:CD002778.

18. Koh, H, Robinson, PG. Occlusal adjustment for treating and preventing temporomandibular joint disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;1:CD003812.

19. Fricton, JR, et al. Critical appraisal of methods used in randomized controlled trials of treatments for temporomandibular disorders. J Orofac Pain. 2010;24:139–151.

20. Kuriyama, T, et al. Bacteriologic features of antimicrobial susceptibility in isolates from orofacial odontogenic infections. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;90:600–608.

21. Burgess, JA, van der Ven, PF, Martin, M, Sherman, J, Haley, J. Review of over-the-counter treatments for aphthous ulceration and results from use of a dissolving oral patch containing glycyrrhiza complex herbal extract. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2008;9:88–98.

22. Chattopadhyay, A, Shetty, KV. Recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2011;44:79–88.

23. Kaur, G, et al. Association between calcium channel blockers and gingival hyperplasia. J Clin Periodontol. 2010;37:625–630.

24. Miller, SA, Miller, G. Use of evidence-based decision making in private practice for emergency treatment of dental trauma: EB case report. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2010;10:135–146.

25. Söder, PO, Otteskog, P, Andreasen, JO, Modéer, T. Effect of drying on viability of periodontal membrane. Scand J Dent Res. 1977;85:164.

26. Hecova, H, Tzigkounakis, V, Merglova, V, Netolicky, J. A retrospective study of 889 injured permanent teeth. Dent Traumatol. 2010;26:466–475.

27. Sigalas, E, Regan, JD, Kramer, PR, Witherspoon, DE, Opperman, LA. Survival of human periodontal ligament cells in media proposed for transport of avulsed teeth. Dent Traumatol. 2004;20:21–28.

28. Mousavi, B, et al. Standard oral rehydration solution as a new storage medium for avulsed teeth. Int Dent J. 2010;60:379–382.

29. McIntosh, MS, et al. Stabilization and treatment of dental avulsions and fractures by emergency physicians using just-in-time training. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54:585–592.

30. Evans, D. Prescribing systemic antibiotics when replanting avulsed teeth. Evid Based Dent. 2009;10:103.

31. Krasner, P. Endodontic treatment of reimplanted avulsed teeth. Dent Today. 2004;23:104–107.

32. Rabelo, GD, de Paula, PM, Rocha, FS, Jordão Silva, C, Zanetta-Barbosa, D. Retrospective study of bone grafting procedures before implant placement. Implant Dent. 2010;19:342–350.

33. Armstrong, BD. Lacerations of the mouth. Emerg Clin North Am. 2000;18:471–480.

34. Lamell, CW, Fraone, G, Casamassiomo, PS, Wilson, S. Presenting characteristics and treatment outcomes for tongue lacerations in children. Pediatr Dent. 1999;21:34–38.

35. Mark, DG, Granquist, EJ. Are prophylactic oral antibiotics indicated for the treatment of intraoral wounds? Ann Emerg Med. 2008;52:368–372.

36. Cheng, D. Unified hands technique for mandibular dislocation. J Emerg Med. 2010;38:366–367.