CHAPTER 23 OPTIC NEUROPATHIES

Virtually every pathological process that can damage an organ in the body can damage the optic nerve. Thus, optic neuropathies can be produced by ischemia, inflammation, infection, compression, infiltration, toxic exposure, metabolic dysfunction, and trauma. Unfortunately, regardless of the cause of an acute optic neuropathy, the optic disc—the only portion of the optic nerve that can be observed with an ophthalmoscope—has only two possible appearances: swollen or normal. Even more confusing is that with chronic damage to the optic nerve, the optic disc simply becomes pale. Thus, the determination of the cause of an optic neuropathy usually cannot be made from the appearance of the optic disc alone. It can, however, be made from a complete assessment, including a complete history, a complete examination, and, in many cases, appropriate ancillary studies.

OPTIC DISC SWELLING WITHOUT VISUAL LOSS

The most common cause of optic disc swelling without visual loss is papilledema. Papilledema is defined as optic disc swelling caused by increased intracranial pressure.1 It may be produced by an intracranial mass, by blockage of the arachnoid villi by blood or protein (e.g., after a subarachnoid hemorrhage or from a spinal cord tumor), by obstruction of flow of cerebrospinal fluid through the ventricles, and by decreased flow of venous blood through dural sinuses.

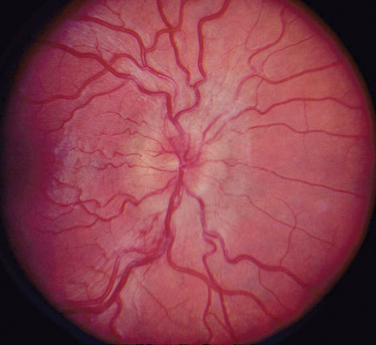

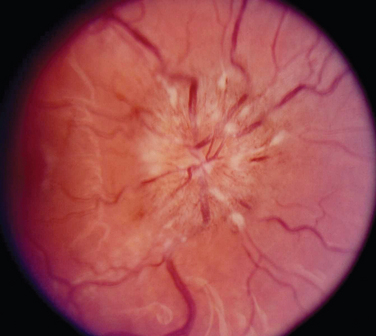

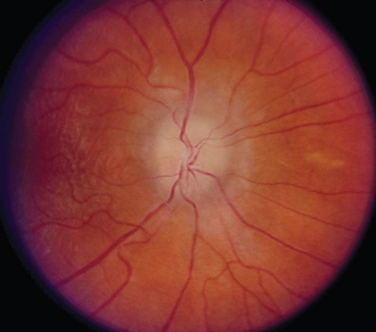

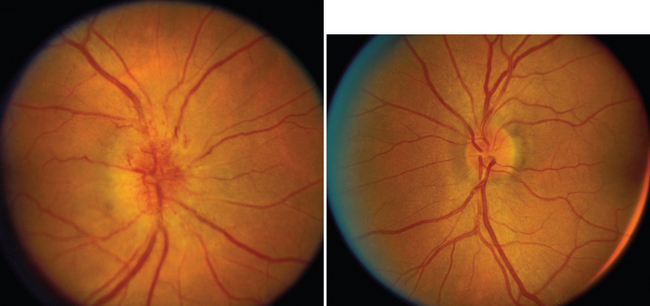

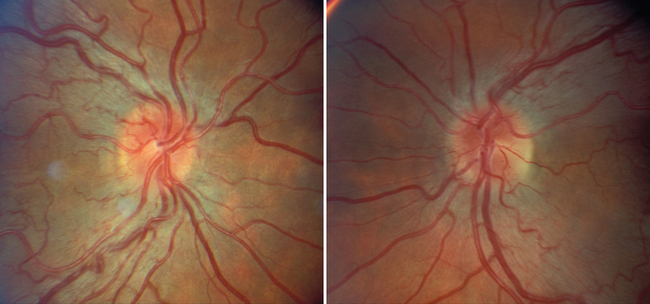

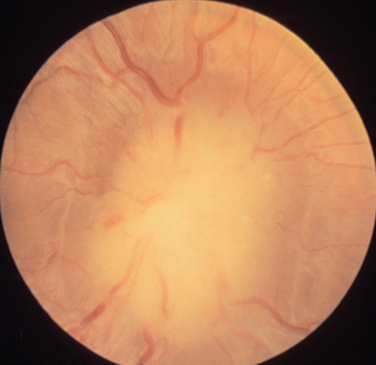

The appearance of papilledema varies with its severity. Early papilledema is characterized by mild swelling and hyperemia of the optic discs (Fig. 23-1). There are often no hemorrhages, and the retinal veins are not dilated. Visual function is usually normal at this time. As papilledema worsens, the disc becomes increasingly swollen and hyperemic, the vessels on the surface of the disc become obscured by the swollen tissue, and peripapillary flame-shaped hemorrhages may appear (Fig. 23-2). Patients with this fully developed papilledema continue to have normal visual acuity and color vision; however, their blind spots are enlarged, and they may have some mild, nonspecific field defects. If intracranial pressure is not lowered, chronic papilledema develops, characterized by a rounding up of the discs, which begin to become pale (Fig. 23-3). During this time, the hemorrhages resolve. The visual acuity may be slightly decreased, but the main visual finding is significant constriction of the visual field. The final stage of papilledema—atrophic papilledema—occurs when the swelling resolves as nerve fibers die, and the optic discs become pallid (Fig. 23-4). At this point, the visual acuity is reduced, and the visual field is markedly constricted, often to only 5 degrees or less.

SUDDEN VISUAL LOSS WITH AND WITHOUT OPTIC DISC SWELLING

Acute Optic Neuritis

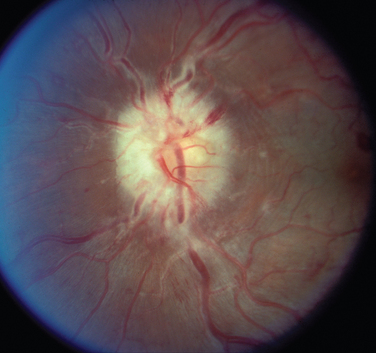

Most patients with optic neuritis are women between 25 and 45 years of age, although this condition can also develop in children and older patients. Optic neuritis is characterized in more than 95% of cases by the sudden onset of pain, often quite severe, behind or around the eye, followed shortly thereafter by decreased central vision and, in many cases, by central field loss.2 The loss of central vision is variable. It may be extremely mild or quite severe; indeed, in some cases, all vision is lost. Affected patients have decreased color vision that may be worse than the acuity would suggest. A relative afferent pupillary defect is always present unless the patient has experienced a previous attack of optic neuritis or has some other optic neuropathy in the opposite eye or the acute process is bilateral. The affected optic disc appears normal in about two thirds of cases; in the other one third, it is swollen (Fig. 23-5).

Figure 23-5 Acute optic neuritis. Note swelling of optic disc associated with perivascular sheathing.

Most cases of optic neuritis are idiopathic or demyelinating in origin; however, rare cases are caused by such inflammatory or infectious conditions as sarcoid, syphilis, Lyme disease, and cat-scratch disease.2

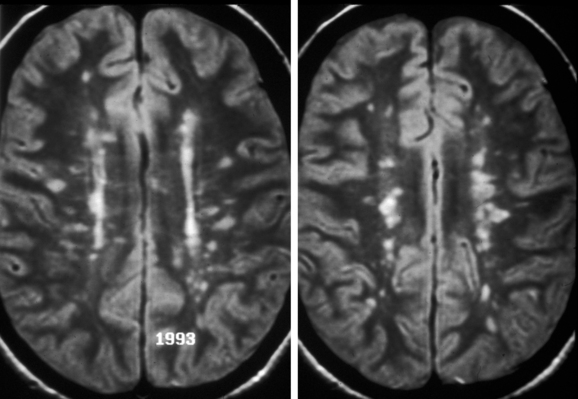

Patients who experience an attack of acute optic neuritis have an increased risk of developing multiple sclerosis, depending in large part on whether white-matter lesions are visible on magnetic resonance images at the time of the acute attack (Fig. 23-6). The presence of even one lesion doubles a patient’s risk of developing multiple sclerosis over the subsequent 10 years.3 Fortunately, there is evidence that the use of interferon β-1a reduces the risk of developing multiple sclerosis in these patients.4

Patients who experience an attack of optic neuritis in one eye have a 10% to 20% risk of developing a similar event in the opposite eye.2 Risk factors for second-eye involvement include white-matter lesions on magnetic resonance images, a family history of multiple sclerosis, and neurological symptoms.

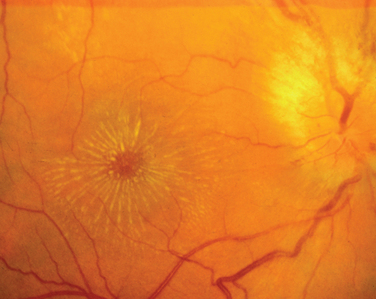

A variant of optic neuritis that has a very different prognosis from the demyelinating or idiopathic form is neuroretinitis.5 This condition begins as an apparently straightforward anterior optic neuritis in which vitreous cells may or may not be present; however, within 1 to 3 weeks, a macular star develops that often persists after the optic disc swelling resolves (Fig. 23-7). Neuroretinitis may be caused by cat-scratch disease, sarcoid, syphilis, tuberculosis, or Lyme disease; however, it is never caused by multiple sclerosis.

Ischemic Optic Neuropathy

The second major cause of acute visual loss with and without optic disc swelling is ION.6 This condition occurs in three main settings: (1) as a complication of systemic noninflammatory vascular diseases, such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia; (2) in the perioperative period, most often after cardiac surgery or back surgery in the prone position; and (3) as a complication of vasculitis, most often temporal (giant cell) arteritis.

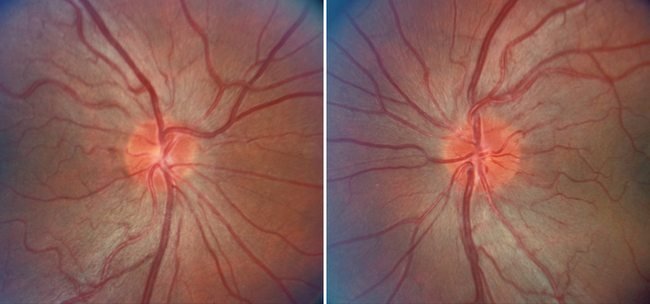

Nonarteritic ION may be of the anterior or the retrobulbar variety.7 In anterior ION, which constitutes about 90% of all cases, the optic disc is usually hyperemic, and peripapillary flame-shaped hemorrhages are often present (Fig. 23-8); however, soft exudates (cotton-wool spots) are usually absent. The opposite optic disc is almost always small with little or no cup (see Fig. 23-8), and this morphological anomaly is believed to predispose the nerve to ischemia by causing crowding of the optic nerve axons. Patients with retrobulbar ION have a normal-appearing optic disc. Because this condition is rare in comparison with anterior ION, retrobulbar ION should be considered a diagnosis of exclusion: that is, other causes of retrobulbar optic neuropathy, particularly an intracranial mass, should be considered.

In about 40% of patients with nonarteritic ION, the condition improves spontaneously, although visual acuity is more likely to improve than is visual field.6 No treatment exists for patients whose vision does not recover. In addition, patients who experience an attack of nonarteritic ION are at risk for subsequent cerebrovascular and cardiovascular events, and such patients have an increased rate of mortality in comparison with age- and gender-matched control subjects.

Patients who experience an attack of nonarteritic ION have a 10% to 20% risk of experiencing a similar attack in the opposite eye.8 Risk factors for opposite eye involvement include advanced age, severe vascular disease, and persistent poor visual acuity in the affected eye.

Perioperative ION occurs most often after back surgery in the prone position and after cardiac surgery in which cardiopulmonary bypass is used. The rates vary from 0.06% to 0.1% after cardiac surgery and from 0.1% to 0.01% after back surgery in the prone position.9,10

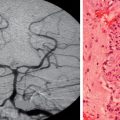

Arteritic ION is the least common type of ION. It is usually associated with temporal (giant cell) arteritis,6 but other vasculitides can be responsible, such as periarteritis nodosa. Patients with this condition do not experience eye pain, but they may have headache, scalp tenderness, jaw pain, ear pain, or a combination of these manifestations. Thus, the physician evaluating a patient with possible arteritic ION must ask specifically about these symptoms.

As with nonarteritic and perioperative ION, arteritic ION may be of the anterior or retrobulbar variety. When the condition is of the anterior type, the optic disc usually shows pallid rather than hyperemic swelling, which indicates a true infarction of the nerve, and one or more soft exudates (cotton-wool spots) are often present (Fig. 23-9). Indeed, in the appropriate clinical setting, the presence of such exudates in a patient with an acute anterior optic neuropathy is almost pathognomonic of arteritic ION.

Leber’s Hereditary Optic Neuropathy

LHON can occur at any age but typically manifests in young adults; about eight times more men than women are affected.11 Visual loss is bilateral and simultaneous in about one half the cases; in the remainder, one eye is affected initially, and the other eye becomes affected, in most cases, within 1 month. Whether unilateral or bilateral, the visual loss is always painless, and this distinguishes the condition from acute optic neuritis, which is almost always associated with pain behind or around the eye, often worsening with eye movement (see previous discussion). The rate of visual loss in LHON is slower than that caused by optic neuritis but faster than that caused by most compressive lesions. The nadir, typically about 20/400, is usually reached within 3 to 6 months. The visual loss is associated with marked color vision loss; a central or cecocentral scotoma with preservation of the peripheral field in most but not all cases; and either a normal-appearing optic disc or the triad of hyperemic “pseudoedema” of disc, telangiectatic vessels on the disc and in the peripapillary region, and no evidence of leakage on fluorescein angiogram (Fig. 23-10).

LHON is a mitochondriopathy. It is, therefore, maternally inherited; more than 90% of cases are caused by mutations at sites 11778 (the most common site), 14484, and 3460. There are a number of other sites at which mutations are responsible for small numbers of cases. Approximately 20% of patients with the pathogenic mutations that cause LHON become symptomatic, but it is not known which factors cause some patients but not others to lose vision. Alcohol abuse, tobacco abuse, and metabolic stress have all been postulated to play a role, but none has been proved to do so.12

The natural history of LHON varies with the site of the mutation.11 Patients with the 11778 mutation have the worst visual prognosis, with a 4% improvement rate, whereas 25% to 40% of patients with mutations at sites 14484 and 3460 experience improvement, often to 20/20 or better. Improvement is associated with breaking up of the central field defects.

INSIDIOUS VISUAL LOSS WITH OR WITHOUT OPTIC DISC SWELLING

Compressive Optic Neuropathy

A compressive optic neuropathy may be unilateral or bilateral.13 When it is unilateral, the optic disc may be swollen or normal in appearance. When it is swollen, the mass is almost always located within the anterior or middle portion of the orbit (Fig. 23-11). When the disc appears normal, the lesion is located in the posterior orbit, in the optic canal, or intracranially. When the visual loss is bilateral, the lesion is almost always intracranial or in the paranasal sinuses, and the optic discs appear normal, at least initially.

Patients suspected of having a compressive optic neuropathy require neuroimaging. When an orbital or paranasal sinus process is suspected, computed tomographic scanning is the optimum imaging modality, whereas intracranial lesions are best detected with magnetic resonance imaging. The treatment of a compressive lesion of the optic nerve depends on the nature of the lesion, as well as its location. Whether a patient improves after successful elimination of the compression process depends in part on how long symptoms have been present and the severity of visual dysfunction before treatment.

Infiltrative Optic Neuropathy

Like compressive optic neuropathies, infiltrative optic neuropathies may be unilateral or bilateral.13 Any level of visual loss can occur, and any type of visual field defect can be present. As with other optic neuropathies, a relative afferent pupillary defect is always present in unilateral cases. Patients with an infiltrative optic neuropathy may have an optic disc that is truly swollen, a disc that appears swollen but that is actually infiltrated with the underlying lesion, or a normal disc. Disorders most likely to produce an infiltrative optic neuropathy include reticuloendothelial disorders, such as leukemia and lymphoma; inflammatory conditions, such as sarcoidosis; and metastatic tumors, particularly carcinomas (Fig. 23-12).

Toxic and Deficiency Optic Neuropathies

These conditions are almost always bilateral, although one eye may be affected days to weeks before the other.14 The loss of vision occurs slowly, usually over one month or more. The eventual nadir is usually about 20/400, except with methanol toxicity, which can cause complete blindness. The visual loss in patients with toxic or deficiency optic neuropathies is virtually always accompanied by bilateral severe loss of color vision, bilateral central or cecocentral scotomas, and optic discs that appear normal or perhaps slightly swollen (Fig. 23-13). Hemorrhages and exudates are almost never seen. Because of the bilaterality of the process, a relative afferent pupillary defect is almost never present. The substances that can cause a toxic optic neuropathy include both common and uncommon medications (Table 23-1).

Nutritional optic neuropathies occur in a number of settings. The most common is chronic alcohol abuse; others include starvation, malabsorption syndromes, fad diets, incorrect vegetarianism, and depression (resulting in a poor diet).15 The diagnosis generally becomes apparent with a careful history of medications being taken, exposures to potential toxins, and eating habits.

OTHER OPTIC NEUROPATHIES

Traumatic Optic Neuropathy

The diagnosis of traumatic optic neuropathy is usually quite easy to establish.16 It usually occurs in the setting of blunt head trauma, in which there is often a period of loss of consciousness. The majority of cases appear to result from damage to the optic nerve within the optic canal, where traumatic hemorrhage and swelling produce severe damage to the optic nerve and its blood supply. The severity of visual loss is variable, from mild loss of visual acuity to no light perception. Although some physicians advocate treatment with systemic corticosteroids and others advocate decompression of the optic nerve within the optic canal, there is no evidence that any intervention is better than the natural history of the process.

Radiation-Induced Optic Neuropathy

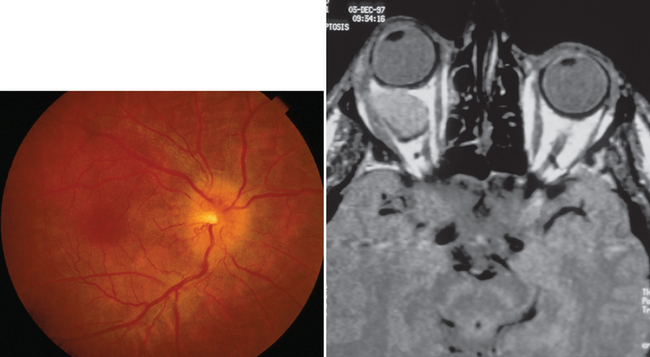

This condition occurs in 10% to 15% of cases in which the optic nerves have received at least 5000cGy.17 The only exceptions appear to be patients with diabetes mellitus and patients receiving chemotherapy for cancer at the time of the irradiation, in which case the condition can occur with smaller doses. A transient type of optic neuropathy can occur during the irradiation itself and is believed to be related to acute swelling of the nerve. This form of optic neuropathy is usually self-limited, and treatment consists of systemic corticosteroids. Most cases of radiation-induced optic neuropathy, however, occur 1 to 8 years after irradiation and consist of a relatively rapid progression of visual loss in one or both eyes, usually associated with an initially normal-appearing optic disc that gradually becomes pale. Neuroimaging in such cases may reveal enhancement and enlargement of one or both optic nerves, but this is not a universal finding (Fig. 23-14).

CONCLUSION

Optic neuropathies. In: Burde RM, Savino PJ, Trobe JD, editors. Clinical Decisions in Neuro-ophthalmology. 3rd ed. St. Louis: CV Mosby; 2002:27-58.

Kline LB. Optic Nerve Disorders. San Francisco: American Academy of Ophthalmology, 1996.

Miller NR, Newman NJ. The Essentials: Walsh & Hoyt’s Clinical Neuro-ophthalmology. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1999;134-322.

Miller NR, Newman NJ, Biousse V, et al, editors. Walsh and Hoyt’s Clinical Neuro-ophthalmology, 6th ed., vol 1. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005.

1 Friedman DI. Papilledema. Miller NR, Newman NJ, Biousse V, et al, editors. Walsh and Hoyt’s Clinical Neuro-ophthalmology, 6th ed., vol 1. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005;237-292.

2 Smith CH. Optic neuritis. Miller NR, Newman NJ, Biousse V, et al, editors. Walsh and Hoyt’s Clinical Neuro-ophthalmology, 6th ed., vol 1. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005;293-348.

3 Optic Neuritis Study Group. High-and low-risk profiles for the development of multiple sclerosis within 10 years after optic neuritis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121:944-949.

4 Jacobs LD, Beck RW, Simon JH, et al. Intramuscular interferon beta-1a therapy initiated during a first demyelinating event in multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:898-904.

5 Williams N, Miller NR. Neuroretinitis. In: Pepose JS, Holland GN, Wilhelmus KR, editors. Ocular Infection and Immunology. St. Louis: CV Mosby; 1996:601-608.

6 Arnold A. Ischemic optic neuropathy. Miller NR, Newman NJ, Biousse V, et al, editors. Walsh and Hoyt’s Clinical Neuro-ophthalmology, 6th ed., vol 1. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005;349-384.

7 Sadda SR, Nee M, Miller NR, et al. Clinical spectrum of posterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;132:743-750.

8 Newman NJ, Scherer R, Langenberg P, et al. The fellow eye in NAION: report from the ischemic optic neuropathy decompression trial follow-up study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;134:317-328.

9 Kalyani SD, Miller NR, Dong LM, et al. Incidence of and risk factors for perioperative optic neuropathy following cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78:34-37.

10 Chang S-H, Miller NR. The incidence of visual loss due to perioperative ischemic optic neuropathy associated with spine surgery: The Johns Hopkins Hospital experience. Spine. 2005;30:1299-1302.

11 Newman NJ. Hereditary optic neuropathies. Miller NR, Newman NJ, Biousse V, et al, editors. Walsh and Hoyt’s Clinical Neuro-ophthalmology, 6th ed., vol 1. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005;465-502.

12 Kerrison JB, Miller NR, Hsu F-C, et al. A case-control study of tobacco and alcohol consumption in Leber hereditary optic neuropathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;130:803-812.

13 Volpe NJ. Compressive and infiltrative optic neuropathies. Miller NR, Newman NJ, Biousse V, et al, editors. Walsh and Hoyt’s Clinical Neuro-ophthalmology, 6th ed., vol 1. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005;385-430.

14 Phillips PH. Toxic and deficiency optic neuropathies. Miller NR, Newman NJ, Biousse V, et al, editors. Walsh and Hoyt’s Clinical Neuro-ophthalmology, 6th ed., vol 1. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005;447-464.

15 Hsu C, Miller NR, Wray M. Optic neuropathy from folic acid deficiency without alcohol abuse. Ophthalmologica. 2002;216:65-67.

16 Steinsapir K, Goldberg RA. Traumatic optic neuropathy. Miller NR, Newman NJ, Biousse V, et al, editors. Walsh and Hoyt’s Clinical Neuro-ophthalmology, 6th ed., vol 1. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005;431-446.

17 Lessell S. Friendly fire: neurogenic visual loss from radiation therapy. J Neuroophthalmol. 2004;24:243-250.