184 Opioids

Pharmacology and Receptor Physiology

Pharmacology and Receptor Physiology

Opioids act as agonists at opioid receptors at presynaptic and postsynaptic sites in various regions of the brain and spinal cord including the periaqueductal gray area of the brainstem, amygdala, corpus striatum, thalamus, and medulla, as well as the substantia gelatinosa (dorsal/posterior horn) in the spinal cord. Opioid receptors are also found in peripheral tissues at afferent pain neurons, in the smooth muscle of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, and intraarticularly. Agonism at opioid receptors decreases neurotransmission through pain neurons, both in the periphery and in the spinal cord. Opioid receptor agonism also diminishes the brain’s perception of pain. This reduction in nerve transmission occurs through alteration of the release of neurotransmitters such as acetylcholine, norepinephrine, dopamine, serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine [5-HT]), glutamate, and substance P. Decreased neurotransmission is thought to be secondary to membrane hyperpolarization or decreased release of neurotransmitters from presynaptic vesicles or both.1

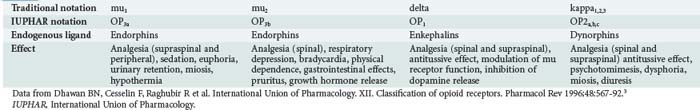

Three major subtypes of opioid receptors have been identified: mu, delta, and kappa. All these are G protein–coupled receptors and have seven transmembrane helices with significant sequence homology. Opioid receptor agonists and antagonists interact with one or more of these receptors with varying affinities.1,2 This Greek-derived nomenclature is commonly used by most of the scientific community. In 1996, the International Union of Pharmacology (IUPHAR) recommended a new nomenclature for opioid receptors, having as a goal consistency in naming with other neurotransmitter systems (Table 184-1).3 The traditional Greek notations are used in this text. Several other new receptor subtypes have been identified. Their clinical significance and classification are unclear at this time.

Pharmacokinetics

Pharmacokinetics

Distribution

Tissue uptake is variable and depends largely on the drug’s lipophilicity. Highly lipophilic compounds such as fentanyl readily penetrate the central nervous system (CNS), the dura of the spinal column, and tissue “reservoirs.” Opioids exhibit varying degrees of plasma protein binding and typically have large volumes of distribution. Serum concentrations of opioids should not be used as a gauge of clinical effect, because fat, skeletal muscle, lungs, and viscera act as reservoirs after opioid administration. Redistribution from saturated tissue depots can produce persistent or recurrent sedation after discontinuation of prolonged infusions of certain opioids such as fentanyl.4

Clinically Important Effects in the Intensive Care Unit

Clinically Important Effects in the Intensive Care Unit

Analgesia, euphoria, sedation, miosis, and respiratory depression are considered to be the classic opioid effects. In addition, opioids have many more clinically relevant effects, many of which are not typically relevant in the intensive care unit (ICU) setting; these are summarized by physiologic system in Table 184-2.

TABLE 184-2 Summary of Clinical Effects of Opioids by Physiologic System

| System | Clinical Effect |

|---|---|

| Cardiovascular | Hypotension (vasomotor centers and histamine), bradycardia (first or second degree), dysrhythmias (overdose, propoxyphene), QRS prolongation (propoxyphene), QT prolongation (methadone) |

| Dermatologic | Urticaria, flushing, pruritus (centrally mediated) |

| Endocrinologic | Reduced release of antidiuretic hormone (controversial), reduced release of gonadotropin |

| Gastrointestinal | Nausea, vomiting (5-HT2 mediated), delayed gastric emptying, constipation, increased smooth muscle tone (biliary tract, intestinal, pylorus, anal sphincter) |

| Genitourinary | Urinary retention, ureteral spasm, decreased renal function and renal blood flow, antidiuresis, priapism (neuraxial use) |

| Immunologic | Mast cell degranulation/histamine release, cytokine stimulation (IL-1), but true allergic reaction is rare |

| Maternal/fetal | Placental transmission, neonatal blood-brain barrier immature, neonatal respiratory depression and opioid dependence, neonatal withdrawal (seizures) |

| Musculoskeletal | Truncal/chest wall rigidity and myoclonus (fentanyl derivatives) |

| Neurologic | Analgesia, euphoria, sedation, psychotomimesis, seizures (meperidine, propoxyphene, tramadol, rarely fentanyl) |

| Ophthalmic | Miosis, normal or dilated pupils (meperidine, pentazocine, diphenoxylate, propoxyphene, severe systemic hypoxia) |

| Pulmonary | Respiratory depression, antitussive effect, bronchospasm, pulmonary edema |

5-HT, serotonin; IL, interleukin.

Analgesia

Opioids are modulators of pain perception both at the level of the CNS and in the periphery. High concentrations of opioid receptors (largely of the mu subtype) are found in areas of the brain that are associated with analgesia. Cortical effects include decreased reception of painful sensory inputs and enhanced inhibitory outflow from the brain to the sensory nuclei of the spinal cord (dorsal root nuclei). In addition, there is decreased neurotransmission from peripheral afferent pain neurons to the spinal cord and from the spinothalamic tract to the brain. The net effect is decreased perception of nociceptive information. Analgesia is mediated by the mu, delta, and kappa opioid receptor subtypes (see Table 184-1). Morphine also appears to be an effective analgesic (via the mu opioid receptor) when administered intraarticularly.5 Tolerance develops to the analgesic effects with repeated use.

Very low doses of naloxone (e.g., 0.25 µg/kg/h) improve the efficacy of morphine analgesia, whereas at higher doses (1 µg/kg/h), analgesia is obliterated by naloxone. The mechanism of this effect is unclear.6

Euphoria

The euphoric effects of opioids are typically described as pleasant, floating sensations accompanied by a decrease in anxiety and distress. Not all exogenous opioids induce the same degree of euphoria. Activation of the mu/delta receptor complex in the ventral tegmental area, followed by dopamine release in the mesolimbic system, is most likely responsible for these effects.7

The degree of lipophilicity and CNS penetration is directly proportional to the euphoric properties of the opioid. For example, heroin, which enters the CNS with relative ease, is associated with greater euphoria than is the less lipophilic opioid, morphine.8 Fentanyl produces euphoric effects akin to those of heroin and is occasionally used as an adulterant in illicitly obtained heroin.9 The apparently enhanced euphoric effect of meperidine may be related to its lipophilicity and its ability to alter serotonergic neurotransmission.

By contrast, pentazocine, an agonist-antagonist opioid (i.e., an agent that is both an agonist at kappa receptors and an antagonist at mu opioid receptors), produces dysphoria and psychotomimesis (psychotic symptoms), an effect that most likely is mediated via kappa2 receptor agonism.10 Pentazocine also can induce a withdrawal syndrome in opioid-tolerant individuals secondary to its mu opioid receptor antagonist effects. For these reasons, many patients previously exposed to pentazocine will cite allergies to it.

Respiratory Depression

All opioid agonists produce dose-dependent depression of ventilation. At equianalgesic doses, all opioid agonists lead to a similar degree of respiratory depression.11,12 In the absence of secondary causes, death from opioid overdose is almost exclusively caused by respiratory depression.

Medullary mu2 receptors are thought to be responsible for the development of respiratory depression. Stimulation of these receptors diminishes chemoreceptor sensitivity to hypercapnia, resulting in loss of hypercarbic ventilatory stimulation.13 Activation of these receptors also decreases the central response to hypoxia13 and inhibits the medullary and pontine respiratory centers that regulate the rhythm of breathing.12 The combination of these effects leads to prolonged pauses between breaths, periodic breathing, hypopnea, bradypnea, and in extreme cases, apnea. It is important to note that the initial manifestation of respiratory depression may be a hypopnea, with or without a decrease in respiratory rate.12

Patients do not develop complete tolerance to the respiratory depressant effects of the opioids.14 For example, patients enrolled in methadone maintenance therapy can experience chronic hypoventilation and hypercapnia.15 A ceiling effect on respiratory depression exists with partial agonist and agonist-antagonist opioids such as nalbuphine and buprenorphine.

Certain groups of patients are particularly sensitive to the ventilatory depressant effects of opioids. These groups include the elderly, patients with chronically elevated PaCO2 (e.g., some patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD]), and patients with a depressed level of consciousness for other reasons. A strong painful stimulus sometimes can transiently overcome or prevent respiratory depression. Similarly, during procedural sedation (e.g., for orthopedic reductions) when pain is relieved, respiratory depression can become apparent. Bronchoconstriction also can occur, most likely as a result of histamine release as well as indirect effects on bronchiolar smooth muscle. Depression of ventilation also can occur in patients receiving neuraxial opioid administration; these effects may be delayed and may be accompanied by respiratory depression (see “Neuraxial Opioids”).

Seizures

Seizures are rare with therapeutic use of most opioids, the primary exception being tramadol. If seizures occur in the setting of an acute opioid overdose, hypoxia is likely the cause. Seizures are associated with meperidine, propoxyphene, and tramadol toxicity. These drugs are further discussed in a later section. In a mouse model, naloxone antagonized the convulsant effects of propoxyphene, but not those of meperidine or its metabolite, normeperidine.16 Fentanyl-induced myoclonus can resemble seizure activity, but true seizures are rarely caused by fentanyl.17

Musculoskeletal Effects: Truncal Rigidity and Movement Disorders

Intravenous (IV) administration of opioids has been associated with motor abnormalities ranging from increased tone to overt myoclonus and involving the chest wall and other truncal muscles. This complication is seen when large doses of highly lipophilic opioids such as fentanyl, sufentanil, remifentanil, or alfentanil are administered rapidly by the IV route.18 Whereas it was previously thought that opioid actions at the level of the spinal cord were responsible for this effect, it now appears that a central dopaminergic effect may be contributory. Both naloxone and neuromuscular blockade can overcome rigidity. Vocal cord spasm, although rare, can cause closure of the vocal cords, leading to difficult bag-valve-mask ventilation. As noted, myoclonic activity resembling seizure activity has been observed in patients after being rapidly infused with large doses of fentanyl.17 Serotonin syndrome, characterized by coarse tremors, increased muscular tone, myoclonus, agitation, and autonomic instability, has been associated with the use of both meperidine and dextromethorphan in combination with other serotonergic agents.

Cardiovascular Effects

The peripheral arterial and venous dilation caused by opioids appears to be mediated by both central depression of vasomotor centers and histamine release.19 Hypotension occurs more frequently in stressed individuals and in those with decreased intravascular volume. Histamine release occurs via non–immunoglobulin (Ig)E-mediated mast cell degranulation.20 Different opioids produce different degrees of histamine release; for example, meperidine and morphine produce much greater release of histamine than fentanyl and sufentanil.21 The severity of histamine-mediated responses can be reduced by slowing the rate of infusion, and hypotension can be reduced by optimizing intravascular volume. Use of Trendelenburg position and saline infusion are appropriate initial interventions for opioid-associated hypotension.

Overall, there are no consistent effects of opioids on cardiac output or the electrocardiogram (ECG). Wide-complex dysrhythmias and impaired contractility are associated with propoxyphene overdose via sodium channel blockade (class Ia antidysrhythmic effect). Illicit opioid use sometimes is associated with cardiac effects secondary to adulterants or co-ingestants; examples are quinine and cocaine (“speedball”). Chronic high-dose methadone use is associated with prolongation of the QT interval.22

Specific Agents

Specific Agents

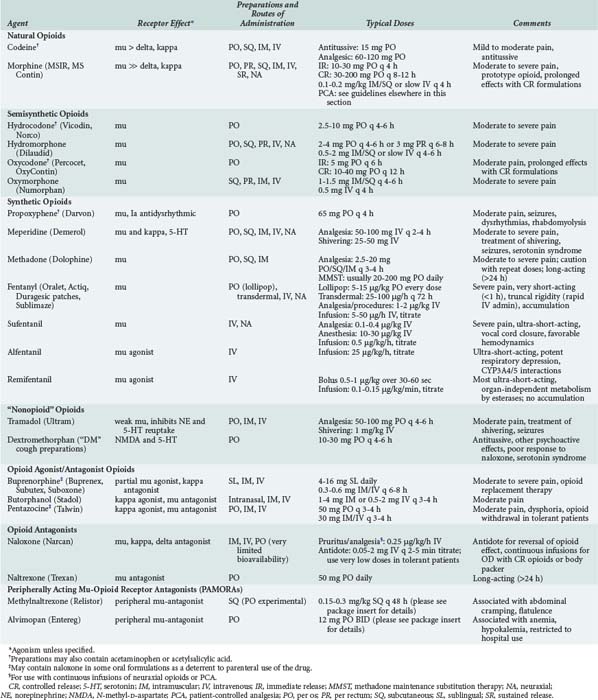

Opioids are among the most widely used drugs in clinical practice. A comprehensive knowledge of their effects and therapeutic applications is essential for any intensive care provider. Table 184-3 summarizes specific agents used in clinical practice.

Heroin

Heroin, also referred to as diacetylmorphine, is a highly lipophilic, semisynthetic opioid produced by acetylation of morphine. Heroin is a prodrug and is devoid of intrinsic opioid effects. It rapidly enters the CNS, where it is deacetylated to the active metabolites, monoacetylmorphine and morphine. Illicit heroin is typically administered by nasal insufflation, SQ injection (i.e., “skin popping”), smoking, or IV injection. The practice of inhaling vapors from heroin heated in aluminum foil is termed “chasing the dragon”; it is associated with a rapidly progressive, irreversible spongiform leukoencephalopathy.23–25

Meperidine

Of special note is meperidine’s extensive hepatic metabolism (90%) to normeperidine, a less potent analgesic eliminated via the kidneys. Normeperidine produces CNS excitation and is associated with myoclonus, delirium, and seizures. Metabolite accumulation occurs primarily in the context of escalating doses and renal failure.26,27 Meperidine also blocks reuptake of serotonin by presynaptic neurons in the CNS, and by this mechanism may produce serotonin toxicity in patients who are taking monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs)28 or other serotonergic drugs (see “Drug Interactions”).29,30 The potential for these side effects, especially seizures, has led to a decline in the popularity of meperidine in many institutions.

Fentanyl, Alfentanil, Remifentanil, and Sufentanil

Around the world, fentanyl is the most widely used of this group of drugs. It has a rapid onset and a short duration of effect and is an important drug for use in the ICU. Fentanyl’s peak effect occurs within 6 to 7 minutes after IV administration. Its very short half-life results from rapid distribution into inactive tissues such as fat, lungs, and skeletal muscle. Prolonged infusions or massive doses may lead to accumulation of the drug within these tissue reservoirs, resulting in prolonged duration of effect after discontinuation of the infusion. Lung uptake of up to 75% of a parenteral dose can occur and is often referred to as first-pass pulmonary uptake. Fentanyl is associated with fewer cardiovascular effects and histamine release than either morphine or meperidine.31 It undergoes extensive hepatic metabolism to norfentanyl, an active metabolite eliminated by the kidneys. Prolonged effects can be seen in the elderly and in patients with renal impairment. Fentanyl-associated myoclonus may resemble seizure activity, but EEGs recorded in these patients failed to show seizure activity.17 Muscle rigidity, particularly of the chest wall, may hamper spontaneous or assisted ventilation. Although this effect can be reversed with naloxone, administration of naloxone simultaneously reduces the analgesic effect of fentanyl.

Alfentanil has the shortest duration of action and the most rapid onset of this group. Alfentanil’s unique metabolism by hepatic cytochrome P4503A (CYP3A4 and 5) enzymes render its metabolism variable and unpredictable. Polymorphisms in the genes coding for these cytochromes and inhibition by other drugs, including some macrolide antibiotics, protease inhibitors, and antifungal agents, such as fluconazole, can make its effects less consistent, particularly when administered by prolonged infusion.32,33

Remifentanil is an ultra-short-acting mu opioid receptor agonist with a unique pharmacokinetic profile. Though it is a 4-anilidopiperidine like fentanyl, alfentanil, and sufentanil, remifentanil is metabolized directly by nonspecific blood and tissue esterases to remifentanil acid (RA). RA is a relatively inactive metabolite. Remifentanil has a terminal half-life of approximately 10 to 20 minutes and a context-sensitive half-life of 2 to 4 minutes, even following prolonged infusions. Time to extubation in mechanically ventilated ICU patients is remarkably short after discontinuing remifentanil (15-45 minutes).34–36 This effect is preserved regardless of the presence of other drugs, disease, or organ failure.37,38 Despite RA’s predominantly renal elimination, and unlike fentanyl and its analogs, renal impairment does not appear to significantly affect time to extubation in patients on continuous infusions of remifentanil.35–3739 The properties of organ-independent metabolism, lack of accumulation, and precision and predictability of onset and offset make remifentanil a promising sole agent or combined agent (often with propofol or midazolam) in analgesia-based sedation in ventilated ICU patients.35–44 As with other opioids, bradycardia, hypotension, muscle rigidity and nausea can occur with remifentanil. Limiting boluses to 0.5 µg/kg is suggested to decrease the incidence of muscle rigidity.35 Whether remifentanil, like other opioids, can reduce cortisol release—a well-established phenomenon in mechanically ventilated and sedated ICU patients—has yet to be determined.45 A recent meta-analysis of remifentanil infusions compared to other regimens in mechanically ventilated ICU patients showed no significant benefit on outcomes such as duration of mechanical ventilation, length of stay, or mortality.36 Remifentanil injections contain glycine and should not be given via neuraxial routes (epidural or intrathecal). Dosing should be based on ideal body weight in obese patients.

Methadone

Methadone is a synthetic opioid with high oral bioavailability and a prolonged duration of action (>24 hours). Its most common use is in substitution therapy for opioid dependence. It is also used as an analgesic in patients with chronic pain. Methadone is hepatically metabolized to inactive metabolites that undergo urinary and biliary excretion. Overall, its side-effect profile resembles that of morphine, although the (desirable and undesirable) effects of methadone persist for substantially longer. Methadone causes less euphoria and less sedation than other opioids. Tolerance to methadone may require escalating doses when it is used for prolonged periods. Methadone at high doses can prolong the QT interval and increase the risk of torsades de pointes.22

Naloxone

Naloxone is a pure competitive antagonist at mu, delta, and kappa opioid receptors. It is commonly used in both prehospital and hospital settings to reverse opioid-induced respiratory depression. The typical prehospital dose of naloxone employed by emergency medical service personnel to treat respiratory depression and/or coma is in the range of 0.4 to 2 mg (IM or IV). However, these high doses often precipitate a dramatic and dangerous withdrawal syndrome in tolerant individuals. Vomiting, aspiration, and severe agitation are common with antagonist-precipitated acute withdrawal (see “Opioid Overdose”). Aspiration is a particular risk after use of naloxone in opioid-dependent patients who have nonopioid causes for their depressed level of consciousness. In these patients, naloxone produces vomiting but does not fully awaken the patient, predisposing to aspiration. It appears to be safer and equally effective in most situations to administer 0.04 to 0.05 mg (40-50 µg) IV and titrate upwards at similar doses every 2 to 3 minutes while providing ventilatory support as needed until the desired clinical response is attained.

Some sources recommend the use of low-dose naloxone infusions (0.25 µg/kg/h) to protect against ventilatory depression and decrease symptoms of pruritus, nausea, and vomiting in patients receiving continuous opioid infusions, in addition to augmenting analgesia.6 In the ICU setting, this approach may benefit patients who are receiving patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) or neuraxial (i.e., epidural or spinal) analgesia.

Of note, orally administered naloxone has very poor bioavailability because of an extensive first-pass effect and therefore produces minimal if any systemic effects. It is included in some oral analgesic preparations as a deterrent to parenteral abuse (see Table 184-3).

Methylnaltrexone and Alvimopan

Methylnaltrexone and alvimopan have been approved recently by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and are members of a new class of drugs: peripherally acting mu opioid receptor antagonists (PAMORAs). In contrast to naloxone, these newly approved drugs do not cross the blood-brain barrier and therefore do not antagonize the central (analgesic) effects of opioids. They act on peripheral opioid receptors only, blocking side effects such as constipation and ileus while preserving centrally mediated analgesia.46–49 Methylnaltrexone (SQ) is also used for the treatment of opioid-induced constipation in patients with advanced cancer and AIDS.50–52 It is administered via the SQ route, although experimentally, higher doses of enteric-coated formulations have been effective in increasing GI motility. Alvimopan (PO) has been approved for the treatment of postoperative ileus following bowel resection.53 PAMORAs, as members of a novel drug class, have led to some realizations concerning the peripheral versus central effects of opioids. It appears that GI motility, pruritus (partly), nausea and vomiting, cough reflex (partly), and urinary retention may be mediated by peripheral opioid receptors. Chronic constipation in patients on chronic methadone maintenance is another area of research.46–49 Interestingly, effects mediated through activation of peripheral opioid receptors also have been implicated as promoting decreased cellular immunity, increased angiogenesis, increased vascular permeability, and increased bacterial lethality (particularly Pseudomonas aeruginosa).46 These are areas of active research in both the basic science and clinical arenas.

Special Clinical Situations

Special Clinical Situations

Opioid Overdose

Naloxone, administered appropriately to reverse symptoms of respiratory depression, can obviate the need for endotracheal intubation in most cases. For example, for opioid overdoses in opioid-dependent patients (e.g., users of prescription analgesics, heroin, or methadone), a starting dose of 0.05 mg IV is indicated, using ventilatory support and rapid titration to higher doses as necessary. The endpoint of reversal should be adequate respiration, not complete reversal of sedation.54 High doses of naloxone (e.g., 1 to 2 mg IV) may be used safely in nontolerant individuals. Continuous infusions may be appropriate for patients who have overdosed with long-acting opioids.55,56 Symptomatic opioid body packers (i.e., people hired to swallow large amounts of tightly wrapped heroin packets and smuggle them across international borders) are likely to require continuous naloxone infusions until the packets are passed or removed.56 Keeping symptomatic patients awake (with naloxone), administering whole-bowel irrigation using polyethylene glycol/electrolyte lavage solution at 0.5 to 2 L/h, and using a bedside commode can facilitate the patient’s passage of the packets. Tolerance and dependence can occur in these patients if “leaking” is protracted. Body packers usually are not opioid users themselves.56

There is some suggestion that the catecholamine surge associated with rapid reversal with naloxone in tolerant individuals can precipitate acute lung injury (i.e., acute noncardiogenic pulmonary edema). Dog models of opioid overdose suggest that hypercapnia may worsen the catecholamine release associated with naloxone administration hemodynamics.57,58 Adequate ventilation to normalize PaCO2 before antagonist administration is suggested to prevent hemodynamic instability. However, no single mechanism is sufficient to explain the development of opioid-associated pulmonary edema, and multiple factors are likely involved. There is an association between naloxone administration and the clinical diagnosis of pulmonary edema. The typical clinical presentation is an obtunded patient with profound respiratory depression who awakens either spontaneously or as the result of antagonist administration. In these situations, it is possible that patients with heroin overdose develop acute lung injury as a result of their respiratory depression or apnea, and that naloxone administration merely unmasks the effects of the opioid by restoring spontaneous respirations.59 This model proposes that hypoxic pulmonary endothelial damage occurs during near-apneic periods. Acute lung injury and/or noncardiogenic pulmonary edema associated with opioid overdose should be treated with standard therapies and supportive care.

If acute withdrawal is precipitated by naloxone, supportive care is recommended. Sedation of an agitated patient experiencing acute withdrawal due to administration of naloxone often leads to even more profound sedation, leading to the necessity for endotracheal intubation once the effects of naloxone wane in 30 to 45 minutes. Withdrawal following naltrexone, a long-acting opioid antagonist, is more complex; some advocate high-dose opioid infusion to overcome the competitive antagonism.60

Drug Interactions

Opioids given in combination with either sedative-hypnotics (e.g., benzodiazepines) or propofol can have a synergistic effect on systemic vascular resistance,61 level of sedation, and respiratory depression.61–65

Meperidine and dextromethorphan are associated with serotonin toxicity. This syndrome typically develops in patients who are simultaneously taking two proserotonergic drugs. Some commonly prescribed proserotonergic drugs include MAOIs, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), valproic acid, lithium, clonazepam, and buspirone. Patients taking proserotonergic drugs should not receive meperidine or dextromethorphan.28–3066 Morphine, fentanyl, and methadone are not associated with serotonin syndrome.

Neuraxial Opioids

The common side effects of neuraxially administered opioids are pruritus, nausea and vomiting, urinary retention (via inhibition of parasympathetic neurons located in the sacral spinal cord), and ventilatory depression. Although early ventilatory depression rarely occurs, depression occurring within 2 hours after administration most likely represents systemic absorption of a lipid-soluble opioid. Delayed respiratory depression can be seen as long as 6 to 12 hours after neuraxial administration and most likely represents cephalad migration of opioid into the CNS.67

The Patient with Pain

In the ICU, analgesic requirements can be substantial, and opioids are often chosen because of their efficacy and predictability. Morphine, hydromorphone, fentanyl, sufentanil, and remifentanil are among the most commonly used opioids in the ICU setting. All modes of delivery are associated with systemic side effects. A more complete discussion of analgesia may be found in Chapter 3.

Key Points

Bailey PL, Egan TD, Stanley TH. Intravenous opioid anesthetics. 5th ed. Miller RD, editor. Anesthesia. vol 1. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2000:273-376.

Chaney MA. Side effects of intrathecal and epidural opioids. Can J Anaesth. 1995;42:891-903.

This review is a thorough discussion of side effects that can occur with neuraxial opioid use.

Moss J, Rosow CE. Development of peripheral opioid antagonists’ new insights into opioid effects. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:1116-1130.

This is a thorough review regarding clinical uses and theoretical applications of PAMORAs.

Nelson LS, Olsen D. Opioids. In: Goldfrank LR, Flomenbaum NE, Lewin NA, et al, editors. Goldfrank’s toxicologic emergencies. 9th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2010:559-578.

Reisine T. Opiate receptors. Neuropharmacology. 1995;34:463-472.

This article is a classic review of opioid receptors and receptor physiology.

Tan JA, Ho KM. Use of remifentanil as a sedative agent in critically ill adult patients: a meta-analysis. Anaesthesia. 2009;64:1342-1352.

Traub SJ, Hoffman RS, Nelson LS. Body packing: the internal concealment of illicit drugs. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2519-2526.

This article is a recent in-depth review of management in opioid body packers.

Wilhem W, Kreuer S. The place for short-acting opioids: special emphasis on remifentanil. Crit Care. 2008;12:S5.

1 Reisine T. Opiate receptors. Neuropharmacology. 1995;34:463-472.

2 Reisine T, Law SF, Blake A, Tallent M. Molecular mechanisms of opiate receptor coupling to G proteins and effector systems. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1996;780:168-175.

3 Dhawan BN, Cesselin F, Raghubir R, et al. International Union of Pharmacology. XII. Classification of opioid receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 1996;48:567-592.

4 Hughes MA, Glass PSA, Jacobs JR. Context sensitive half-time in multiple compartment pharmacokinetic models for intravenous anesthetic drugs. Anesthesiology. 1992;76:334-341.

5 Christensen O, Christensen P, Sonnenschein C, et al. Analgesic effect of intraarticular morphine: A controlled, randomized and double-blind study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1996;40:842-846.

6 Crain SM, Shen KF. Antagonists of excitatory opioid receptor functions enhance morphine’s analgesic potency and attenuate opioid tolerance/dependence liability. Pain. 2000;84:121-131.

7 Nestler EJ. Under siege: The brain on opiates. Neuron. 1996;16:897-900.

8 Smith GM, Beecher HK. Subjective effects of heroin and morphine in normal subjects. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1962;136:47-52.

9 LaBarbera M, Wolfe T. Characteristics, attitudes and implication of fentanyl use based on reports from self-identified users. J Psychoactive Drugs. 1983;15:293-301.

10 Pfeiffer A, Brantl V, Herz A, Emrich HM. Psychotomimesis mediated by kappa opiate receptors. Science. 1986;233:774-776.

11 Eckenhoff JE, Oech SR. The effects of narcotics and antagonists upon respiration and circulation in man. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1960;1:483-524.

12 Shook JE, Watkins WD, Camporesi EM. Differential roles of opioid receptors in respiration, respiratory disease, and opiate-induced respiratory depression. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;142:895-909.

13 Weil JV, McCullough BS, Kline JS, Sodal IE. Diminished ventilatory response to hypoxia and hypercapnia after morphine in normal man. N Engl J Med. 1975;21:1103-1106.

14 Santiago TV, Pugliese AC, Edelman NH. Control of breathing during methadone addiction. Am J Med. 1977;62:347-354.

15 Marks CE, Goldring RM. Chronic hypercapnia during methadone maintenance. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1973;108:1088-1093.

16 Gilbert PE, Martin WR. Antagonism of the convulsant effects of heroin, d-propoxyphene, meperidine, normeperidine and thebaine by naloxone in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1975;192:538-541.

17 Smith NT, Benthuysen JL, Bickford RG. Seizures during opioid anesthetic induction: Are they opioid-induced rigidity? Anesthesiology. 1989;71:852-862.

18 Bowdle TA, Rooke GA. Postoperative myoclonus and rigidity after anesthesia with opioids. Anesth Analg. 1994;78:783-786.

19 Fahmy NR, Sunder N, Soter NA. Role of histamine in the hemodynamic and plasma catecholamine responses to morphine. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1983;33:615-620.

20 Barke KE, Hough LB. Opiates, mast cells and histamine release. Life Sci. 1993;53:1391-1399.

21 Flacke JW, Flacke WE, Bloor BC, et al. Histamine release by four narcotics: A double blind study in humans. Anesth Analg. 1987;66:723-730.

22 Krantz MJ, Kutinsky IB, Robertson AD, Mehler PS. Dose-related effects of methadone on QT prolongation in a series of patients with torsades de pointes. Pharmacotherapy. 2003;23:802-805.

23 Wolters EC, van Wijngaarden GK, Stam FC. Leucoencephalopathy after inhaling “heroin” pyrolysate. Lancet. 1982;ii:1233-1237.

24 Sempere AP, Posada I, Ramo C, Cabello A. Spongiform leucoencephalopathy after inhaling heroin. Lancet. 1991;338:320.

25 Tan TP, Algra PR, Valk J, Wolters EC. Toxic leukoencephalopathy after inhalation of poisoned heroin: MR findings. Am J Neuroradiol. 1994;15:175-178.

26 Armstrong PJ, Berston A. Normeperidine toxicity. Anesth Analg. 1986;65:536-538.

27 Stone PA, Macintyre PE, Jarvis DA. Normeperidine toxicity and patient controlled analgesia. Br J Anaesth. 1993;59:576-577.

28 Browne B, Linter S. Monoamine oxidase inhibitors and narcotic analgesics: A critical review of the implications for treatment. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;151:210-212.

29 Sporer KA. The serotonin syndrome: Implicated drugs, pathophysiology and management. Drug Saf. 1995;13:94-104.

30 Weiner AL. Meperidine as a potential cause of serotonin syndrome in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6:156-158.

31 Rosow CE, Moss J, Philbin DM, et al. Histamine release during morphine and fentanyl anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 1982;56:93-96.

32 Klees TM, Sheffels P, Thummel KE, Kharasch ED. Pharmacogenetic determinants of human liver microsomal alfentanil metabolism and the role of cytochrome P450 3A5. Anesthesiology. 2005;102:550-556.

33 Klees TM, Sheffels P, Dale O, Kharasch ED. Metabolism of alfentanil by cytochrome P4503a (CYP3a) enzymes. Drug Metab Dispos. 2005;33:303-311.

34 Wilhem W, Kreuer S. The place for short-acting opioids: special emphasis on remifentanil. Crit Care. 2008;12:S5.

35 Wilhelm W, Dorscheid E, Schlaich N, Niederprüm P, Deller D. The use of remifentanil in critically ill patients. Clinical findings and early experience. Anaesthetist. 1999;48:625-629.

36 Tan JA, Ho KM. Use of remifentanil as a sedative agent in critically ill adult patients: a meta-analysis. Anaesthesia. 2009;64:1342-1352.

37 Breen D, Wilmer A, Bodenham A, Bach V, et al. Offset of pharmacodynamic effects and safety of remifentanil in intensive care unit patients with various degrees of renal impairment. Crit Care. 2004;8:R21-R30.

38 Dershwitz M, Hoke JF, Roscow CE, Michalowski P. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamics of remifentanil in volunteer subjects with severe liver failure. Anaesthesiology. 1996;84:812-820.

39 Pitsiu M, Wilmer A, Bodenham A, Breen D, Bach V, et al. Pharmacokinetics of remifentanil and its major metabolite, remifentanil acid, in ICU patients with renal impairment. Br J Anaesth. 2004;92:493-503.

40 Beers R, Camporesi E. Remifentanil update: clinical science and utility. CNS Drugs. 2004;18(15):1085-1104.

41 Breen D, Karabinis A, Malbrain M, Morais R, et al. Decreased duration of mechanical ventilation when comparing analgesia-based sedation using remifentanil with standard hypnotic-based sedation for up to 10 days in intensive care unit patients: a randomised trial [ISRCTN47583497]. Crit Care. 2005;9:R200-R210.

42 Battershill AJ, Keating GM. Remifentanil: a review of its analgesic and sedative use in the intensive care unit. Drugs. 2006;66:365-385.

43 Karabinis A, Mandragos K, Stergiopoulos S, Komnos A, et al. Safety and efficacy of analgesia-based sedation with remifentanil versus standard hypnotic-based regimens in intensive care unit patients with brain injuries: a randomised, controlled trial [ISRCTN50308308]. Crit Care. 2004;8:R268-R280.

44 Rozendaal FW, Spronk PE, Snellen FF, et al. Remifentanil-propofol analog-sedation shortens duration of ventilation and of ICU stay compared to a conventional regimen: a centre randomized, cross-over, open label study in the Netherlands. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35:291-298.

45 Daniell HW. Does remifentanil shorten ventilator maintenance, midazolam prolong it, or both alter its duration? Intensive Care Med. 2009;35:1649.

46 Moss J, Rosow CE. Development of peripheral opioid antagonists’ new insights into opioid effects. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:1116-1130.

47 Garnock-Jones KP, McKeage K. Methylnaltrexone. Drugs. 2010;70:919-928.

48 Becker G, Blum HE. Novel opioid antagonists for opioid-induced bowel dysfunction and postoperative ileus. Lancet. 2009;373:1198-1206.

49 Mehta. Peripheral opioid antagonism. Anaesthesia. 2009;64:1279-1282.

50 Thomas J, Karver S, Cooney GA, et al. Methylnaltrexone for opioid-induced constipation in advanced illness. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2332-2343.

51 Diego L, Atayee R, Helmons P, von Gunten CF. Methylnaltrexone: a novel approach for the management of opioid-induced constipation in patients with advanced illness. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;3:473-485.

52 Earnshaw SR, Klok RM, Iyer S, McDade C. Methylnaltrexone bromide for the treatment of opioid-induced constipation in patients with advanced illness–a cost-effectiveness analysis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31:911-921.

53 Erowele GI. Alvimopan (Entereg), a peripherally acting mu-opioid receptor antagonist for postoperative ileus. P T. 2008;33:574-583.

54 Nelson LS, Olsen D. Opioids. In: Goldfrank LR, Flomenbaum NE, Lewin NA, et al, editors. Goldfrank’s Toxicologic Emergencies. 9th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2010:559-578.

55 Goldfrank L, Weisman RS, Errick JK, Lo MW. A dosing nomogram for continuous infusion intravenous naloxone. Ann Emerg Med. 1986;15:566-570.

56 Traub SJ, Hoffman RS, Nelson LS. Body packing: The internal concealment of illicit drugs. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2519-2526.

57 Mills CA, Flacke JW, Flacke WE, et al. Narcotic reversal in hypercapnic dogs: Comparison of naloxone and nalbuphine. Can J Anaesth. 1990;37:238-244.

58 Mills CA, Flacke JW, Miller JD, et al. Cardiovascular effects of fentanyl reversal by naloxone at varying arterial carbon dioxide tensions in dogs. Anesth Analg. 1988;67:730-736.

59 Duberstein JL, Kaufman DM. A clinical study of an epidemic of heroin intoxication and heroin-induced pulmonary edema. Am J Med. 1971;51:704-714.

60 Lubman D, Koutsogiannis Z, Kronborg I. Emergency management of inadvertent accelerated opiate withdrawal in dependent opiate users. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2003;22:433-436.

61 Tomicheck RC, Rosow CE, Philbin DM, et al. Diazepam-fentanyl interaction-hemodynamic and hormonal effects in coronary artery surgery. Anesth Analg. 1983;62:881-884.

62 Stanley TH, Webster LR. Anesthetic requirements and cardiovascular effects of fentanyl-oxygen and fentanyl-diazepam-oxygen anesthesia in man. Anesth Analg. 1978;57:411-416.

63 Vuyk J. Clinical interpretation of pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic propofol-opioid interactions. Acta Anaesth Belg. 2001;52:445-451.

64 Vuyk J. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic interactions between opioids and propofol. J Clin Anesth. 1997;9:23S-26S.

65 Tverskoy M, Fleyshman G, Ezry J, et al. Midazolam-morphine sedative interaction in patients. Anesth Analg. 1989;68:282-285.

66 Boyer EW, Shannon M. The serotonin syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1112-1120.

67 Chaney MA. Side effects of intrathecal and epidural opioids. Can J Anaesth. 1995;42:891-903.