CHAPTER 14 Opioid Analgesics

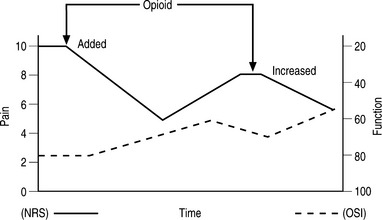

The use of opioid analgesics is an important part of the practice of pain medicine. Most physicians who treat chronic low back pain (CLBP) will prescribe opioid analgesics for well-selected patients at some time. Opioids are usually prescribed for CLBP when pain has proven refractory to rehabilitation, therapeutic injections, and less potent primary and adjunctive analgesics. Pharmacological treatment should be just one part of a comprehensive plan to improve pain and function (Fig. 14.1).

Fig. 14.1 The four primary types of pain.

(Adapted from Woolf CJ. Pain: moving from symptom control toward mechanism-specific pharmacologic management. Ann Intern Med 2004; 140(6): 441–451).

OPIOID ANALGESICS

The efficacy and safety of long-term opioid analgesics specifically for CLBP has been reviewed recently, and much of the following discussion regarding efficacy appears from that paper.1 There are now multiple randomized, controlled trials that consistently demonstrate efficacy and safety of opioid therapy for patients with CLBP.2–11 The strongest evidence comes from numerous prospective randomized, placebo-controlled trials (PRPCT) that compared a particular opioid to placebo.12 Katz et al. performed a 12-week enriched enrollment PRPCT to compare pain relief of oxymorphone-ER to placebo in 325 opioid-naive patients with CLBP.2 During titration, 120 patients discontinued treatment for reasons that included lack of efficacy and adverse events. In the 205 remaining patients who obtained adequate analgesia and tolerable side effects during titration, pain intensity measured by visual analogue scale (VAS) decreased from 69 mm to 23 mm. These patients were subsequently randomized to continue oxymorphone-ER or placebo. After 12 weeks, the opioid group had statistically better pain numerical rating scores and patient satisfaction scales. There were 34 patients in the oxymorphone group who discontinued treatment for reasons that included lack of efficacy (12 patients) and adverse events (9 patients). In the placebo group, 53 discontinued treatment for similar reasons, lack of efficacy (35 patients) and adverse events. The authors concluded that oxymorphone-ER was safe and effective for opioid-naive patients with CLBP.

Hale et al. performed a 12-week enriched enrollment PRPCT to compare pain relief of oxymorphone-ER to placebo in 250 opioid-experienced patients with CLBP.3 Function was not addressed. During the titration period, 108 patients discontinued treatment due to adverse events (47), lack of efficacy (7), among other reasons. In 143 remaining patients who obtained adequate analgesia and tolerable side effects during titration, there were significant decreases in pain. These patients were subsequently randomized to continue oxymorphone-ER or placebo. After 12 weeks, there were clinically better outcomes in the oxymorphone-ER group for both numerical rating and patient satisfaction scales. There were 20 patients in the oxymorphone group who discontinued treatment due to lack of efficacy (8), adverse events (7), or other reasons. In the placebo group there were 55 who discontinued treatment due to lack of efficacy (39), adverse events (8) including opioid withdrawal (5), or other reasons. These authors also concluded that oxymorphone-ER was safe and effective for opioid-experienced patients with CLBP.

Hale et al. reported an 18-day multicenter randomized, double-blind, active and placebo-controlled comparison of oxymorphone-ER, oxycodone-CR, and placebo in 213 patients with CLBP.4 The mean change in pain intensity was significantly greater in both opioid-treated groups compared to placebo, and there were no clinically meaningful differences between opioids. Categorical pain ratings were most impressive. About 35% of the opioid-treated groups described their pain as absent or mild versus 12% in the placebo group. Sixty-one percent of the opioid groups reported moderate to complete pain relief versus 28% of the placebo group. Conversely, 45% of the placebo group described their pain as severe versus 14% in the opioid groups. There were statistically significant improvements in general activity, mood, normal work, and enjoyment of life, but not walking ability. During the titration phase about 15% of opioid-treated patients withdrew due to side effects and 4% due to lack of efficacy. In the treatment phase, 25–33% of the opioid groups withdrew due to adverse effects. There were no instances of addictive behavior. Side effects were common, but only sedation and constipation were more frequent in the opioid groups compared to controls.

Peloso and associates performed a 91-day randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled study comparing the efficacy and safety of flexible dose tramadol 37.5 mg plus acetaminophen (APAP) 325 mg to placebo in 338 patients with CLBP.5 The active treatment group had statistically and significantly better improvements in pain (VAS) and function (Roland Disability Questionnaire) compared to placebo patients. About 49% of the active treatment patients had ≥30% reduction in pain and 49% had ≥50% relief. The number needed to treat was 4 for ≥30% relief and 5 for ≥50% relief.

Schnitzer et al. reported a prospective randomized, controlled 4-week trial that compared tramadol to placebo in 254 patients with CLBP who had had been shown to be tramadol responders in the open-label phase of the study.6 The tramadol group had significantly greater improvements in pain (VAS) and function (Roland) compared to the control group. Ruoff and associates reported a 91-day PRCT that compared tramadol plus acetaminophen to placebo in patients with CLBP.7 The active treatment group had significantly better pain (VAS) and function compared to placebo.

There are also numerous prospective, randomized active-control trials (PRACT) that compared opioids to one another.8–11,13,14 Rauck et al. performed an 8-week open-label PRACT to compare effectiveness and safety of a once-a-day morphine sulfate-SR (Avinza®) with twice daily oxycodone-CR (Oxycontin®) in 392 patients with moderate to severe CLBP.8 Both groups had statistically and clinically significant reductions in pain. Although there were slightly better outcomes in the morphine group, the authors recognize that the study protocol mandated 12-hour dosing of the oxycodone-CR rather than 8-hour dosing that is more often necessary. This may have biased the results slightly in favor of the morphine group. Numerical rating scale (NRS) decreased from a mean of about 6.5 to a mean of 3.4–3.7. The morphine-SR group had somewhat smoother pain control. Function was not addressed. About 32–43% of patients withdrew, most often due to side effects, but also due to inadequate pain relief. There were four instances of abuse or diversion in the oxycodone-CR group.

Allan et al. performed a 13-month unblended, randomized parallel group study to compare titrated doses of transdermal fentanyl (TDF) to morphine-SR in 680 patients with CLBP.9 Doses of drugs were titrated according to individual patient response. The TDF and morphine-SR produced similar results. Depending on level of activity, 50–65% of patients described themselves as improved, and 37–53% of patients had at least 50% reduction in pain. There were significant improvements in mean SF-36 scores for physical functioning, bodily pain, role-physical, vitality, social function and role-emotional. About 31–37% of patients withdrew the due to adverse events. Over the 13 months of the study, opioid doses increased only slightly, usually early in treatment, and were attributed to titration to optimal dose rather than tolerance. There were no instances of addiction or abuse behavior.

Hale et al. performed a 10-day randomized, double-blind trial to compare the efficacy and safety of titrated doses of oxycodone-CR and to oxycodone-IR in 47 CLBP patients.10 There were equal and significant improvements with both formulations. Pain intensity decreased from moderate to severe at baseline to slight at the end of titration with both oxycodone formulations. Eleven patients (23%) withdrew due to side effects.

Jamison et al. performed a 16-week randomized, prospective study to compare naproxen, fixed dose oxycodone, and a titrated dose of oxycodone plus morphine-ER in 36 patients.11 All three groups had improvement in pain, activity level, and emotional distress. The titrated dose opioid group did best with less pain and less emotional distress than the other two groups. Both opioid groups were better than the naproxen group. There were 86% who found opioids beneficial. Three patients in the opioid groups withdrew due to side effects and one patient had an abuse problem.

In addition, there are multiple prospective observational studies that have shown consistent findings of efficacy and safety for opioids in patients with CLBP. Simpson et al. found statistically significant improvement in pain in 50 patients changed to TDF compared to their prior regimens of pain-contingent oral opioids for chronic LBP.13 Gammaitoni et al. prospectively studied 33 patients with CLBP treated with titrated doses of oxycodone-IR plus APAP three times daily for 4 weeks.14 Three patients were not able to tolerate the oxycodone and two others withdrew for other reasons. The mean NRS was reduced from 6.4 to 4.4 and worst pain from 7.7 to 5.6. There were significant improvements in general activities, mood, walking tolerance, and sleep. Side effects were common, but there were no serious adverse effects. There were no instances of addictive behavior or other abuse.

Recently, Martell and associates published a systematic review of opioid treatment for CLBP.15 Despite the fact that the authors did not include several PRPCTs that showed both efficacy and safety of opioids for CLBP, they still concluded that opioids ‘may be efficacious for short-term pain relief.’2,6,7,9 They also state that ‘long-term efficacy is unclear.’ However, they did not include the study with the longest duration of 13 months9 and gave less weight to other long-term studies that are of lower quality but provide the best available evidence.16,17

While it is clear that the evidence regarding long-term efficacy and safety of opioid use is not strong, there are several prospective observational and retrospective studies that are consistent in showing long-term efficacy and safety and no studies that demonstrate loss of effectiveness over time unless there is disease progression.16,17 Schofferman reported a prospective case series of 33 patients with refractory CLBP treated with opioids for 1 year.16 There were no control or comparison groups. The specific opioid was selected by response during the trial titration phase. Five (15%) patients withdrew because of side effects. In the remaining 28, there were statistically and clinically significant improvements in pain and function at one year. The mean NRS improved from 8.6 to 5.9 and mean Oswestry Low Back Disability Index (OSI) from 64 to 54. There was a biphasic response. In 21 patients there was an improvement of NRS from 8.45 to 4.9, while 7 others had no change. Overall, of the 33 patients who started the study, opioids were beneficial in 21 (64%).

Mahowald et al. reviewed their experience with opioid use over a period of 3 years in an orthopedic spine clinic.17 Opioids were prescribed for 152 patients, 58 of whom received opioids long term. There was adequate follow-up in 117. Pain was reduced from a mean of 8.3 to 4.5. It is noteworthy that there was no significant dose increase over time and the authors stated that they did not see tolerance in their patients. Side effects were common but well tolerated by most patients. There was a low prevalence of abuse. The authors concluded that there was clinical evidence to support treating CLBP patients with opioids.

There are multiple studies and systematic reviews that examined the efficacy and safety of opioid analgesics for the treatment of chronic musculoskeletal pain, all of which included but were not limited to patients with CLBP. Furlan’s meta-analysis of opioids for chronic pain concluded that opioids were more effective than placebo for pain and functional outcomes in patients with nociceptive pain, including CLBP.18 With respect to side effects, only nausea and constipation were clinically and statistically significantly greater in the opioid than placebo patients. Study withdrawal rates averaged 33% in the opioid groups and 38% in placebo groups.

The MONTAS study group performed a 2-week prospective, randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of MS-ER in 48 patients, 12 of whom had refractory CLBP.19 In 17 (35%) patients, pain was reduced from a mean of 7.4 to 2.9 (excellent responders). In 17 others, pain was reduced from 7.8 to 5.6 (partial responders). In 14 (29%) (non-responders) there was either no meaningful relief or intolerable side effects. Markenson et al. performed a 90-day RCT comparing oxycodone-CR to placebo in 107 patients with moderate to severe osteoarthritis, 40–50% of whom had CLBP.20 There were statistically significant differences favoring the oxycodone-CR group versus controls in pain intensity, pain-induced interference with general activity, walking, work, mood, sleep, and enjoyment in life. The improvements in pain were only modest. The discontinuation rate was similar between groups, either due to inadequate pain control or side effects.

OPIOIDS: CELLULAR MECHANISM OF ACTION

There is evidence that points to the involvement of N-methylD-aspartate (NMDA) receptors in the development and maintenance of neuropathic pain.21 It follows that NMDA receptor antagonists may be helpful in the treatment of neuropathic pain. However, in order to obtain complete analgesia, a combination of an NMDA receptor antagonist and an opioid receptor agonist may be needed. In vitro data have demonstrated some medications (such as methadone), in addition to being opioid receptor agonists, are also weak noncompetitive NMDA receptor antagonists.21

CLINICAL CONCERNS REGARDING LONG-TERM OPIOID THERAPY

Lack of knowledge of medical standards, current research and clinical guidelines for appropriate pain treatment;

Lack of knowledge of medical standards, current research and clinical guidelines for appropriate pain treatment; The perception that prescribing adequate amounts of controlled substances will result in unnecessary scrutiny by regulatory authorities;

The perception that prescribing adequate amounts of controlled substances will result in unnecessary scrutiny by regulatory authorities;Some physicians continue to have a bias against the use of long-term opioid analgesics for chronic pain. The most prevalent concerns are organ toxicity, tolerance, dependency, addiction and fear of legal consequences, and at least in theory the development of opioid-induced hyperalgesia. In addition, there is a concern that the side effects may outweigh benefits.

Tolerance

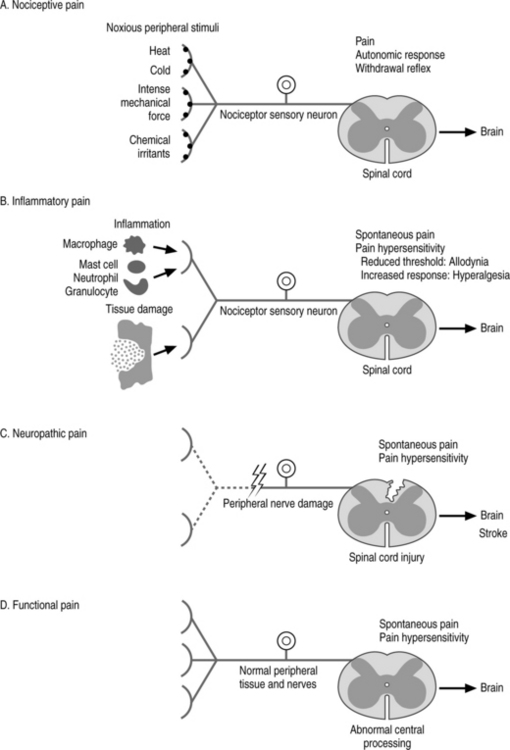

Tolerance is the need for progressively higher doses of an analgesic to produce the same degree of pain relief, which would translate into partial loss of opioid efficacy over time. True tolerance is a biological process at the cellular level based on downregulation of opioid receptors, desensitization of receptors or both.22 True tolerance is not common in the clinical setting. Once the proper balance of pain control, function, and side effects has been reached; there is rarely dose escalation unless there is disease progression. Early in treatment it is common to note ‘pseudotolerance,’ the need for increased dosage due to an increase in function, which in turn is due to better pain control. The development of pseudotolerance requires rebalancing the opioid dose for maximal pain control and function with minimal adverse effects. When tolerance appears to occur well after stable doses have been reached, it is most likely due to diseases progression. However, the other factors that must be considered include lack of compliance, change in other medications with unexpected drug interaction and diversion of medications (Fig. 14.2).23

Opioid-induced hyperalgesia

EXPERIMENTAL EVIDENCE: More of the recently published data show decrease in the dose–response effects of opioids on nociception during acute administrations in animals. This decline in antinociceptive efficacy is much more rapidly observed with short-acting opioids than with long-acting opioids.24 Mao et al. and Kissin et al. both demonstrated progressive reduction of baseline nociceptive thresholds (allodynia) in rats receiving repeated morphine and alfentanil.25,26 Laulin et al. reported an obvious relationship between acute tolerance and hyperalgesia in rats receiving a repeated once-daily dose of heroin.27 A progressive decrease in heroin analgesic effects was combined with a gradual lowering of the nociceptive threshold. This same group reported that opioid-induced hyperalgesia is dose-dependent.28 The larger the dose of subcutaneous fentanyl bolus, the more noticeable was the reduction of baseline nociceptive thresholds. In this study, decreased baseline nociceptive thresholds lasted as long as 5 days after the cessation of four fentanyl bolus injections. Opioid-induced hyperalgesia is also time-dependent. In a 2002 study, allodynia following an opioid infusion was increased with longer opioid infusions in comparison to shorter ones.29

CLINICAL EVIDENCE: In volunteers, tolerance to analgesia during remifentanil infusion at a constant rate for 4 hours was profound and developed very rapidly within 60–90 minutes after the start of infusion.30 Some authors report delayed hyperalgesia from shortacting opioid exposure.31–33 Some other data show the larger the intraoperative opioid dose, the greater was postoperative opioid consumption and the higher were the pain scores.34–36

Dependence and addiction

DEPENDENCE: Dependence is a state of physiological adaptation induced by the chronic use of a psychoactive substance, which would include alcohol and opioids. There is an abstinence syndrome when the drug is suddenly stopped or the dose is reduced rapidly.37 Dependence is very common in patients treated with opioids, but it is rarely a clinical problem. Physical dependence and tolerance are normal physiological consequences of extended opioid therapy for pain and are not the same as addiction (Table 14.1).

| Dependence | Addiction | |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | It is characterized by a strong psychological dependence and an overpowering compulsion to continually take opioids | Compulsive physiological and psychological need for a habit-forming substance |

| Mechanism | Psychological | Neurobiological with environmental, genetic and psychosocial influences |

| Characteristics | Abstinence syndrome associated with discontinued use or decreased intake | Abnormal behavior including impaired control, compulsivity, continuation of use despite harm |

| Considered normal physiological end-result of chronic opioid use | Considered abnormal outcome of use of opioids |

GUIDELINES

The California Medical Board has adopted the following criteria when evaluating the physician’s treatment of pain, including the use of controlled substances.38

Periodic review

The physician should periodically review the course of treatment and any new information about the etiology of the pain or satisfactory response to treatment may be indicated by the patient’s decreased pain, increased level of function, or improved quality of life. If the patient’s progress is unsatisfactory, the physician should consider a different opioid. If treatment continues to be unsatisfactory, opioids may need to be discontinued. There will be the need for frequent visits during initiation of opioid therapy and early dose and drug titration, perhaps as frequently as weekly. Once patients are stable, they should be seen at least quarterly in most instances.

Compliance with controlled substances laws and regulations

To prescribe, dispense, or administer controlled substances, the physician must be licensed in the state and comply with applicable federal and state regulations. Physicians are referred to The Practitioner’s Manual of the US Drug Enforcement Administration (and any relevant documents issued by the state medical board) for specific rules governing controlled substances as well as applicable state regulations (Table 14.2).

| PATIENT EVALUATION | |

| Detailed medical and pain history | |

| Physical examination | |

| Review of imaging | |

| Review of medical records | |

| A treatment plan that states the goals of therapy | |

| Informed consent and agreement for treatment | |

| Potential risks, probable and possible side effects | |

| Consequences of abuse, diversion, or illicit use of opioids | |

| Periodic review | |

| EFFICACY | |

| Side effects | |

| Signs of abuse or diversion | |

| Consultation when necessary with specialists in psychology/psychiatry | |

| Chemical dependence | |

| The maintenance of good medical records | |

| Compliance with controlled substances laws and regulations | |

PRACTICAL ASPECTS OF OPIOID USE

Routes of administration and doses

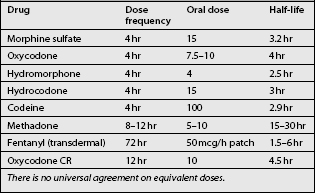

For the treatment of chronic pain, CR or LA opioids are administered orally or transdermally. The dose and dosing interval is adjusted based on the degree and duration of pain relief experienced by the patient versus side effects until there is good control of baseline pain with tolerable side effects. There is no best or correct drug nor is there a best or correct dose. There are many drug choices available, some of which are listed in Table 14.3. In addition, the patient should be provided with a prescription for ‘rescue doses’ of an immediate-release (rapid-onset, short-acting) opioid available for breakthrough pain or flares.

Side effects

As mentioned earlier in this chapter, the side effect profile also affects prescribing pattern and frequency of opioid use. The mechanisms and treatment of opioid side effects have been studied extensively in the literature.39 Most side effects are not serious and can be managed by the use of adjuvant medications. The decision whether to continue opioid analgesic therapy depends on the balance of improved pain, improved function, and side effects.

NAUSEA AND VOMITING: Nausea or vomiting occurs frequently in patients on opioids. They are more common in opioid-naive patients, and often subside after days to weeks despite continued use.39 There are several potential causes including stimulation of the chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ), gastric stasis and stimulation of vestibular centers. Stimulation of the CTZ usually responds to oral medications such as prochlorperazine or haloperidol (suppositories may be needed initially). Gastric stasis usually responds to metoclopramide. Patients with nausea due to vestibular stimulation feel ill with head rotation. They may respond to antihistamines such as meclizine.

SEDATION: Sedation is common, especially at the onset of opioid treatment or when the dose is raised. It usually improves in days or weeks of continued treatment. If the opioid is effective, but there is excess sedation, modafinil or methylphenidate can be of value.40

COGNITIVE CHANGES: Cognitive changes are potential side effects that concern treating physicians. It is important to note that severe chronic pain has been shown to cause decreased cognitive abilities, and if opioids improve pain, cognitive abilities may actually improve.41,42 Many patients feel just a bit ‘off,’ but state the minor side effect is worth the realized pain reduction. Delirium can potentially occur in the elderly or patients with significant medical illnesses. The combination of opioids and long-acting benzodiazepines may be particularly prone to cause sedation or other neuropsychological side effects.43

PRURITUS: Several mechanisms have been proposed including the direct stimulation of ‘itch receptors’ and the release of histamine from mast cells.39 It is important to note pruritus is not an allergic reaction. Treatment with antihistamines is occasionally helpful.

OPIOID-INDUCED HORMONAL CHANGES AND SYMPTOMS: The two hormonal systems mainly affected by opioids are hypothalamicpituitary-adrenal axis and the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis. In both animal studies44,45 and human studies,46 morphine has been reported to cause a progressive decline in the plasma cortisol level. The effects of opioids on the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis are changes in hormonal release, including an increase in prolactin and a decrease in LH, FSH, testosterone, and estrogen levels.47 In methadone maintenance patients, heroin addicts, and patients on intrathecal morphine, a drop in testosterone is seen and is associated with decreased libido, aggression, and drive; amenorrhea or irregular menses; and galactorrhea.48–51 These patients may benefit from testosterone replacement therapy.52

SPECIFIC OPIOIDS

No one opioid has been shown to be superior for chronic use. The eventual choice of opioid is based on finding the best balance point between efficacy and side effects. It is now clear that there are individual variations among patients with respect to which opioid will work best for a particular patient.53 This phenomenon may be genetic and there is an emerging field of ‘pharmacological genomics’ that eventually hopes to make these laboratory observations clinically useful.

At the initiation of opioid therapy it may be necessary to try several before the optimal opioid is identified for a particular patient based on pain control and side effects. If a patient does not respond to the initial opioid, even after appropriate dose escalation, it makes sense to try a second or a third before considering the pain unresponsive to opioids. It also may make sense to rotate to another opioid if there are significant side effects with the initial drug. In fact, in a retrospective review, about 36% of patients responded well to the first opioid tried, 40% to the second and 56% to the third.54

| c3400 BC | The opium poppy is cultivated in lower Mesopotamia. The Sumerians refer to it as Hul Gil, the ‘joy plant’. |

| 460 BC | Hippocrates, the father of medicine, acknowledges usefulness of opium as a narcotic and styptic in treating internal diseases, diseases of women and epidemics. |

| 1300s | Opium had become a taboo subject for those in circles of learning during the Holy Inquisition. |

| 1527 | Opium is reintroduced into European medical literature by Paracelsus as laudanum. These black pills or ‘Stones of Immortality’ were made of opium the baicum, citrus juice and quintessence of gold, and prescribed as painkillers. |

| 1729 | Chinese emperor, Yung Cheng, issues an edict prohibiting the smoking of opium and its domestic sale, except under license for use as medicine. |

| 1803 | Friedrich Sertürner of Paderborn, Germany discovers the active ingredient of opium by dissolving it in acid then neutralizing it with ammonia. The result: alkaloids – Principium somniferum or morphine. |

| 1827 | E. Merck & Company of Darmstadt, Germany, begins commercial manufacturing of morphine. |

| 1843 | Dr Alexander Wood of Edinburgh discovers a new technique of administering morphine, injection with a syringe. He finds the effects of morphine on his patients instantaneous and three times more potent. |

| 1874 | English researcher, C.R. Wright first synthesizes heroin, or diacetylmorphine, by boiling morphine over a stove. |

| 1902 | In various medical journals, physicians discuss the side effects of using heroin as a morphine step-down cure. Several physicians would argue that their patients suffered from heroin withdrawal symptoms equal to morphine addiction. |

| JANUARY 2004 | Consumer groups file a lawsuit against Oxycontin maker Purdue Pharma. The company is alleged to have used fraudulent patents and deceptive trade practices to block the prescription of cheap generic medications for patients in pain. |

| DECEMBER 2004 | McLean pain-treatment specialist Dr William E. Hurwitz is sent to prison for allegedly ‘excessive’ prescription of opioid painkillers to chronic pain patients. Testifying in court, Dr Hurwitz describes the abrupt stoppage of prescriptions as ‘tantamount to torture’. |

It is noteworthy that the most expensive component of treatment for chronic LBP may be medications. In view of the current crisis in healthcare finance, it is reasonable to consider cost as one of the many factors used to determine the choice of opioid. However, evidence-based medicine is directed toward obtaining the best outcomes for the most patients under most circumstances. Cost is a societal problem that must be considered, but best patient care is paramount.

Methadone

Methadone is gaining in popularity as an analgesic among pain specialists because it is effective, has high biologic availability, has no known active metabolites, and has no known neurotoxicity.55 Further, it has a theoretical advantage of having fewer opioid-induced hyperalgesic side effects. It is also far less expensive than other opioids.

Transdermal fentanyl

Transdermal fentanyl (TDF) is an effective analgesic for long-term use. The transdermal route is particularly useful for patients who have difficulty with oral absorption and for those with severe opioid-induced constipation. The patch is commonly changed every 3 days but in some patients there is the need to change the patch every 48 hours. One disadvantage to TDF is the loss of ability to vary doses at different times of day for those patients with predictable daily activity cycles. It is important to have an immediate-release opioid available for breakthrough pain until the final effective dose of fentanyl is established.

Oxymorphone (Opana-ER)

Oxymorphone is the newest opioid and perhaps it is the best studied specifically for the treatment of CLBP.3,4 It is administered twice daily with oxymorphone-IR available for breakthrough pain. The average final dose of oxymorphone-ER in study patients was 39–79 mg per day.

Tramadol

Tramadol is a semisynthetic opioid that is available alone or combined with acetaminophen, and is also available in an extended-release formulation. It has been shown to be effective in patients with CLBP.5–7 The mean final dose in several studies was about 158 mg per day. The maximum safe daily dose is 400 mg daily. The drug is both an opioid agonist and an inhibitor of serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake. As a result of the latter mechanism, concomitant administration with antidepressants of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor class (SSRIs) risks development of a ‘serotonin syndrome.’

Meperidine (Demerol™)

Meperidine (Demerol™) should not be used as a long-term oral opioid analgesic. Its primary metabolite, normeperidine, is neurotoxic. Normeperidine can accumulate over days to weeks and cause generalized hyperexcitablity and even seizures. Since there are better alternatives to this medication, we do not recommend this medication for pain of spine origin (see Table 14.2).

1 Schofferman J, Mazenak D. Opioid analgesic therapy. Spine J (in press).

2 Katz N, Rauck R, Ahdieh H, et al. A 12 week, randomized, placebo-controlled trial assessing the safety and efficacy of oxymorphone extended release for opioid-naïve patients with chronic low back pain. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23:117-128.

3 Hale M, Ahdieh H, Ma T, et al. Efficacy and safety of OPANA-ER (oxymorphone extended release) for relief of moderate to severe chronic low back pain in opioid-experienced patients: a 12-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Pain. 2007;8:175-184.

4 Hale M, Dvergsten C, Gimbel J. Efficacy and safety of oxymorphone extended release in chronic low back pain: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo and active-controlled phase III study. J Pain. 2005;6:21-28.

5 Peloso P, Fortin L, Beaulieu A, et al. Analgesic efficacy and safety of tramadol/acetaminophen combination Tablets (Ultracet®) in treatment of chronic low back pain: a multicenter, outpatient, randomized, double blind, placebo controlled trial. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:2454-2463.

6 Schnitzer T, Gray W, Paster R, et al. Efficacy of tramadol in treatment of chronic low back pain. J Rheumatol. 2000;27:772-778.

7 Ruoff G, Rosenthal N, Jordan D, et al. Tramadol/acetaminophen combination tablets for the treatment of chronic lower back pain: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled outpatient study. Clin Ther. 2003;25:1123-1141.

8 Rauck R, Bookbinder S, Bunker T, et al. The ACTION study: a randomized, open-label, multicenter trial comparing once-a-day extended-release morphine sulfate capsules (Avinza®) to twice-a-day controlled-release oxycodone hydrochloride tablest (OxyContin®) for the treatment of chronic, moderate to severe low back pain. J Opioid Manag. 2006;2:155-166.

9 Allan L, Richarz U, Simpson K, et al. Transdermal fentanyl versus sustained release oral morphine in strong-opioid naïve patients with chronic low back pain. Spine. 2005;30:2484-2490.

10 Hale ME, Fleisschmann R, Salzman R, et al. Efficacy and safety of controlled-release versus immediate-release oxycodone: randomized, double-blind evaluation in patients with chronic back pain. Clin J Pain. 1999;15:179-183.

11 Jamison RN, Raymond SA, Slawsby EA, et al. Opioid therapy for chronic noncancer back pain. A randomized prospective study. Spine. 1998;23:2591-2600.

12 Katz N. Methodological issues in clinical trials of opioids for chronic pain. Neurology. 2005;65(S4):833-849.

13 Simpson RK, Edmondson EA, Constant CF, et al. Transdermal fentanyl as treatment for chronic low back pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1997;14:218-224.

14 Gammaitoni AR, Gaier BS, Lacouture P, et al. Effectiveness and safety of new oxycodone/acetaminophen formulations with reduced acetaminophen for the treatment of low back pain. Pain Med. 2003;4:21-30.

15 Martell B, O’Connor P, Kerns R, et al. Systematic review: opioid treatment for chronic back pain: prevalence, efficacy, and association with addiction. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:116-127.

16 Schofferman J. Long-term opioid analgesic therapy for severe refractory lumbar spine pain. Clin J Pain. 1999;15:136-140.

17 Mahowald M, Singh J, Majeski P. Opioid use by patients in an orthopedic spine clinic. Arthrit Rheumat. 2005;52:312-321.

18 Furlan A, Sandoval J, Mailis-Gagnon A, et al. Opioids for chronic noncancer pain: a meta-analysis of effectiveness and side effects. CMAJ. 2006;174:1589-1594.

19 Maier C, Hildebrandt J, Klinger R, et al. Morphine responsiveness, efficacy and tolerability in patients with chronic non-tumor associated pain – results of a double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Pain. 2002;97:223-233.

20 Markenson J, Croft J, Zhang P, et al. Treatment of persistent pain associated with osteoarthritis with controlled-release oxycodone tablets in a randomized controlled clinical trial. Clin J Pain. 2005;21:524-534.

21 Ebert B, Thorkildsen C, Andersen S, et al. Opioid analgesics as noncompetitive N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) antagonists. Biochem Pharmacol. 1998;56(5):553-559.

22 Ballantyne J, Mao J. Opioid therapy for chronic pain. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1943-1953.

23 Pappagallo M. The concept of pseudotolerance to opioids. J Pharm Care Pain Symptom Control. 1998;6:95-98.

24 Kissin I, Brown PT, Bradley ELJr. Magnitude of acute tolerance to opioids is not related to their potency. Anesthesiology. 1991;75:813-816.

25 Mao J, Price DD, Mayer DJ. Thermal hyperalgesia in association with the development of morphine tolerance in rats: roles of excitatory amino acid receptors and protein kinase C. J Neurosci. 1994;14:2301-2312.

26 Kissin I, Bright CA, Bradley ELJr. The effect of ketamine on opioid-induced acute tolerance: can it explain reduction of opioid consumption with ketamine-opioid analgesic combinations? Anesth Analg. 2000;91:1483-1488.

27 Laulin JP, Célèrier E, Larcher A, et al. Opiate tolerance to daily heroin administration: an apparent phenomenon associated with enhanced pain sensitivity. Neuroscience. 1999;89:631-636.

28 Célèrier E, Rivat C, Jun Y, et al. Long-lasting hyperalgesia induced by fentanyl in rats: preventive effect of ketamine. Anesthesiology. 2000;92:465-472.

29 Ho ST, Wang JJ, Huang JC, et al. The magnitude of acute tolerance to morphine analgesia: concentration-dependent or time-dependent? Anesth Analg. 2002;95(4):948-951.

30 Vinik HR, Kissin I. Rapid development of tolerance to analgesia during remifentanil infusion in humans. Anesth Analg. 1998;86:1307-1311.

31 Koppert W, Dern S, Sittl R, et al. A new model of electrically evoked pain and hyperalgesia in human skin: the effects of intravenous alfentanil, S(+)-ketamine, and lidocaine. Anesthesiology. 2001;95(2):395-402.

32 Koppert W, Alsheimer M, Sittl R, et al. Remifentanil-induced hyperalgesia in new human pain model. Anesthesiology. 2001;95:A861.

33 Petersen KL, Jones B, Segredo V, et al. Effect of remifentanil on pain and secondary hyperalgesia associated with the heat-capsaicin sensitization model in healthy volunteers. Anesthesiology. 2001;94(1):15-20.

34 McQuay HJ, Bullingham RE, Moore RA. Acute opiate tolerance in man. Life Sci. 1981;28(22):2513-2517.

35 Chia YT, Liu K, Wang JJ, et al. Intraoperative high dose fentanyl induces postoperative fentanyl tolerance. Can J Anaesth. 1999;46:872-877.

36 Guignard B, Bossard AE, Coste C, et al. Acute opioid tolerance: intraoperative remifentanil increases postoperative pain and morphine requirement. Anesthesiology. 2000;93:409-417.

37 Liaison Committee on Pain and Addiction. Definitions related to the use of opioids for the treatment of pain. www.ampainsoc.org/advocacy/opioids2.htm, 2001.

38 Medical Board of California. Guidelines for prescribing controlled substances for pain (revised). Action Report: Medical Board of California. 2003;87:1-4.

39 McNicol E, Horowicz-Mehler N, Fisk RA, et al. Management of opioid side effects in cancer-related and chronic noncancer pain: a systematic review. J Pain. 2003;4:231-256.

40 Webster L, Andrews M, Stoddard G. Modafinil treatment of opioid-induced sedation. Pain Med. 2003;4:135-140.

41 Tassain V, Attal N, Fletcher D, et al. Long term effects of oral sustained release morphine on neuropsychological performance in patients with chronic non-cancer pain. Pain. 2003;104:389-400.

42 Jamison RN, Schein JR, Vallow S, et al. Neuropsychological effects of long-term opioid use in chronic pain patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;26:913-921.

43 Ciccone D, Just N, Bandilla E, et al. Psychological correlates of opioid use in patients with chronic nonmalignant pain. A preliminary test of the downhill spiral hypothesis. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;20:180-192.

44 Collu R, Clermont MJ, Ducharme JR. Effects of thyrotropin-releasing hormone on prolactin, growth hormone and corticosterone secretions in adult male rats treated with pentobarbital or morphine. Eur J Pharmacol. 1976;37:133-140.

45 Bartolome MB, Kuhn CM. Endocrine effects of methadone in rats: acute effects in adults. Eur J Pharmacol. 1983;95:231-246.

46 Rolandi E, Marabini A, Franceschini R, et al. Changes in pituitary secretion induced by an agonist–antagonist opioid drug, buprenorphine. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh). 1983;104:257-260.

47 Malaivijitnond S, Varavudhi P. Evidence for morphine-induced galactorrhea in male cynomolgus monkeys. J Med Primatol. 1998;27:1-9.

48 Mendelson JH, Mendelson JE, Patch VD. Plasma testosterone levels in heroin addiction and during methadone maintenance. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1975;192:211-217.

49 Mendelson JH, Meyer RE, Ellingboe J, et al. Effects of heroin and methadone on plasma cortisol and testosterone. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1975;195:296-302.

50 Rasheed A, Tareen IA. Effects of heroin on thyroid function, cortisol and testosterone level in addicts. Pol J Pharmacol. 1995;47:441-444.

51 Malik SA, Khan C, Jabbar A, et al. Heroin addiction and sex hormones in males. J Pak Med Assoc. 1992;42:210-212.

52 Abs R, Verhelst J, Maeyaert J, et al. Endocrine consequences of long-term intrathecal administration of opioids. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:2215-2222.

53 Galer BS, Coyle N, Pasternak G, et al. Individual variability in the response to different opioids: report of five cases. Pain. 1992;49:87-91.

54 Quang-Cantagrel N, Wallace M, Magnuson S. Opioid substitution to improve the effectiveness of chronic non-cancer pain control: a chart review. Anesth Analg. 2000;90:933-937.

55 Fishman SM, Wilsey B, Mahajan G, et al. Methadone reincarnated: novel clinical applications with related concerns. Pain Med. 2002;3:339-348.

Banki CM, Arato M. Multiple hormonal responses to morphine: relationship to diagnosis and dexamethasone suppression. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1987;12:3-11.

Brodner R, Taub A. Chronic pain exacerbated by long-term narcotic use in patients with non-malignant disease: clinical syndrome and treatment. Mt Sinai J Med. 1978;45:233-237.

Collin E, Poulain P, Gauvain-Piquard A, et al. Is disease progression the major factor in morphine ‘tolerance’ in cancer pain treatment? Pain. 1993;55:319-326.

Compton P, Athanasos P, Eloashoff D. Withdrawal hyperalgesia after acute opioid physical dependence in nonaddicted humans: a preliminary study. J Pain. 2003;4:511-519.

Craig D. Is the word ‘narcotic’ appropriate in patient care? J Pain Palliative Care Pharmacother. 2006;20:33-34.

Dalman FC, O’Malley KL. Opioid tolerance and dependence in cultures of dopaminergic midbrain neurons. J Neurosci. 1999;19(14):5750-5757.

Daniell H. Hypogonadism in men consuming sustained-action oral opioids. Pain Med. 2002;3:377-384.

Fanciullo G, Ball P, Giralut G, et al. An observational study of the prevalence and pattern of opioid use in 25,479 patients with spine and radicular pain. Spine. 2002;27:201-205.

Federation of State Medical Boards of the United States, Inc. Model policy for the use of controlled substances for the treatment of pain. Online Available: http://www.fsmb.org/pdf/2004_grpol_Controlled_Substances.pdf, 2004.

Finch PM, Roberts LJ, Price L, et al. Hypogonadism in patients treated with intrathecal morphine. Clin J Pain. 2000;16:251-254.

Gallagher R, Welz-Bosna M, Gammaitoni A. Assessment of dosing frequency of sustained release opioid preparations in patients with chronic nonmalignant pain. Pain Med. 2007;8:71-74.

Haddox J, Jordanson D, Angarola R, et al. The use of opioids for the treatment of chronic pain. A consensus statement from the American Academy of Pain Medicine and the American Pain Society. Glenview IL: 1997.

Hale ME, Fleisschmann R, Salzman R, et al. Efficacy and safety of controlled-release versus immediate-release oxycodone: randomized, double-blind evaluation in patients with chronic back pain. Clin J Pain. 1999;15:179-183.

Jamison RN, Raymond SA, Slawsby EA, et al. Opioid therapy for chronic noncancer back pain. A randomized prospective study. Spine. 1998;23:2591-2600.

Lotsch J, Geisslinger G. Current evidence for a genetic modulation of the response to analgesics. Pain. 2006;121:1-5.

MacLaren J, Gross R, Sperry J, et al. Opioid use and functional restoration. Clin J Pain. 2006;22:392-398.

Maier C, Hildebrandt J, Klinger R, et al. Morphine responsiveness, efficacy and tolerability in patients with chronic non-tumor associated pain – results of a double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Pain. 2002;97:223-233.

Marcus D, Glick R. Sustained-release oxycodone dosing survey of chronic pain patients. Clin J Pain. 2004;30:363-366.

Miyoshi H, Leckband S. Systemic opioid analgesics. In: Loeser J, Butler S, Chapman C, et al, editors. Bonica’s management of pain. New York: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001:1682-1709.

Novak S, Nemeth W, Lawson K. Trends in medical use and abuse of sustained-release opioid analgesics: a revisit. Pain Med. 2004;5:59-65.

Portenoy RK. Fields HL, Liebeskind JC, editors. Pharmacological approaches to the treatment of chronic pain. Seattle, WA: IASP Press, 1994.

Portenoy R, Foley K. Chronic use of opioid analgesics in non-malignant pain: report of 38 cases. Pain. 1986;25:171-186.

Rashiq S, Koller M, Haykowsky M, et al. The effect of opioid analgesia on exercise test performance in chronic low back pain. Pain. 2003;106:119-125.

Rowbotham M, Twilling L, Davies P, et al. Oral opioid therapy for chronic peripheral and central neuropath pain. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1223-1232.

Schofferman J. Long-term opioid analgesic therapy for severe refractory lumbar spine pain. Clin J Pain. 1999;15:136-140.

Vogt M, Kwoh K, Dope D, et al. Analgesic usage for low back pain: impact on health care costs and service use. Spine. 2005;30:1075-1081.

Woolf CJ. Pain: moving from symptom control toward mechanism-specific pharmacologic management. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140(6):441-451.