Chapter 2. Operations management: the search for value in healthcare organisation and performance

Sandra Leggat

Introduction

If corporations have glass ceilings, then hospitals have concrete floors. What happens above in the general management seems awfully disconnected – in activity if not quite in consequences – from what happens below in clinical operations.

(Mintzberg 2002:197)

In most organisations a set of activities creates value by transforming inputs into outputs. The outputs are products or services. Operations management, broadly defined as the planning, management and control of these activities (‘the operations’), is a fundamental component of management practice. Operations research, management science or industrial engineering apply mathematical or statistical models to operating issues to guide management practice and improve operations. In many industries operations management has been key to productivity and quality improvements.

Effective management of clinical care processes, which are the fundamental operations of a healthcare organisation, is essential for a well-functioning healthcare system. Yet it is only recently that the healthcare sector has recognised the relevance of operations management. Well-established operations management approaches, such as six sigma; lean thinking; root cause analysis; failure mode and effect analysis; queuing theory; modelling and simulation; and supply chain logistics, have become recent additions to the health services management repertoire (see Warburton, Chapter 9).

This chapter provides the context for taking up operations management in managing clinical processes in healthcare. ‘Traditional’ clinical and managerial processes have been accepted as the basis for healthcare service planning, delivery and evaluation. But, as outlined in Chapter 1, healthcare systems throughout the world are experiencing pressure to change – consumer influence, competition, changes in public policy, and advances in technology and clinical practice require review of traditional processes. Effective clinical process management requires understanding of those variables that have the power to significantly improve healthcare processes, and ultimately the performance of the healthcare system. This chapter explores the reasons why process management is difficult in healthcare and suggests future directions to improve clinical care processes.

Operations management – a sound management discipline

Operations management originated with the industrial revolution in the 1700s. Up until this time consumers received their products and services from individual craftspeople. While the individual form of craft production is still evident today, the industrial revolution facilitated the widespread production of consumer goods. This mass production was based on inventions ranging from the division of labour, Eli Whitney’s introduction of standardised parts in 1790, the principles of scientific management and the invention of the computer, which allowed complex analysis and modelling. These foundations of mass production enabled significant savings through economies of scale, largely achieved through standardising tasks to shorten production time and reduce variation and human error.

Unfortunately mass production also created problems in defining, measuring and ensuring quality. No longer was one craftsperson accountable for, and in control of, the product quality throughout the production process. Early approaches to quality control focused on finding defects and removing them at the end of the production process. As knowledge of production processes improved, scholars suggested that this inspection-based approach could be replaced with error prevention. In the early 1920s statistical process control was introduced to manufacturing processes to reduce errors. W Edward Deming used statistical process control and his knowledge of management to improve production in the US during World War II, and then introduced statistical control to Japanese manufacturers. Joseph Juran added a human dimension to quality control, suggesting the need for managers to be trained in quality methods. This requirement of training was not accepted in the US and Juran became known for his success in improving Japanese quality control after the war (see also Boaden & Harvey, Chapter 10).

The next wave of operations management innovation focused on lean manufacturing with just-in-time systems and processes. This meant that producers no longer had to store large inventories and products were ‘pulled’ through only those processes that added value, based on customer demand (Bowen & Youngdahl 1998). Efficiencies were achieved by grouping inputs with similar process requirements and by reducing set-up times. Importantly, lean structures shifted the responsibility for quality control from inspectors and quality departments to individual workers and teams (Bowen & Youngdahl 1998). These advances in operations management illustrate an ongoing cycle where a product is introduced and then continuously improved until a ‘final’ ultimate product is achieved. Once the preferred design has been identified, the focus of innovation moves to the production processes. In comparison with manufacturing, the health service sector has not found either the perfect design or the most appropriate processes.

Operations management – necessary, but insufficient in healthcare

Although operations management has been around since the industrial revolution, in healthcare we have been slow to capitalise on the analysis techniques and improvement methods of this discipline to manage clinical operations. There are some examples: In the late 1990s American hospitals advanced clinical process improvement and innovation (CPI) to decrease costs and improve quality (Savitz 2000) and by 1995 over 60% of US hospitals reported use of clinical process management (Walston et al 2000). But in comparison with other industries, where processes are designed to operate correctly 98–99% of the time, in healthcare studies have shown that clinical care processes may be defective 50% of the time (Resar 2006, Scott et al 2004, Runciman et al 2006). While healthcare has assumed some aspects of effective operations management, it is patchy and sub-optimal in comparison with other industries. Specialisation and standardisation are two principles that have transformed the operations of many industries but which have had mixed success in healthcare. Each is discussed briefly in the context of healthcare.

Specialisation in healthcare

There is an over-abundance of specialisation in workforce inputs in healthcare. Specialisation, or division of labour, defines the extent to which tasks in an organisation are subdivided into separate jobs. In healthcare, this is commonly based on professional expertise and clinical specialties. More than one hundred health professions can be identified, and within only one of these professions there are over 130 medical specialties. In Australia, while we continue to support this abundance of specialists, we have difficulty maintaining adequate numbers of practitioners within many individual specialties. The increasing specialisation of healthcare has required mechanisms to facilitate interdependence among the workers involved in a patient’s care. The boundaries of these professional groups and an individual’s hierarchical rank reduce information sharing (Edmondson 1996) making it difficult to manage care processes effectively. This has led to the hospital being referred to as the ‘key battleground for the various forces arrayed in the division of labour in healthcare’ (Dingwall et al 1988:228). While it is acknowledged that ‘quality comes from improving processes, which invariably cut across professional and functional boundaries’ (Buck 1998:752), the organisation of healthcare has not kept pace. The necessary inter-disciplinary and inter-departmental coordination are neither encouraged, nor rewarded.

In other industries specialisation has been effective in improving production processes, with a focus on ensuring specialisation of inputs other than the workforce, as well as specialisation of processes and outputs. While there is abundance of specialisation among healthcare providers, researchers have commented that unlike other industries, specialisation in other inputs (such as equipment, facilities, and even patients) has not been seen to be linked to improved clinical outcomes (Ramanujami & Rousseau 2006:823). Most recently ‘lean thinking’ approaches have been adapted from car manufacturers to healthcare settings and have resulted in an increasing focus on structuring service delivery to increase specialisation among patient inputs (Ben-Tovim et al 2007, Kelly et al 2007). The concept of the hospital as a ‘focused factory’, with highly specialised services consolidated in a relatively small number of sites, and with greater differentiation of patient types between emergency-driven hospitals and elective care (Leung 1999), is a good example of how specialisation of manufacturing production process can be adapted to the hospital setting.

Standardisation in healthcare

Standardisation has offered savings through efficiencies in many industries. Standardisation is broadly defined as the process of establishing agreed technical standards to achieve benefits for an organisation or industry. Standardisation can be applied to all parts of production – the inputs, the production processes and the outputs – and defines the specifications of the components in these parts, that is, the desired technical standards. In healthcare, like specialisation, standardisation is primarily directed to the competencies of health professionals (Glouberman & Mintzberg 2001b), with professional colleges and registration bodies structured to ensure standards of practice. While this aim has ensured standardisation of the largest proportion of the inputs, standardisation of other inputs (such as equipment and supplies) has not reached the levels achieved in other industries that have enabled efficient operations. Recently, standardisation of other inputs in healthcare has increased patient safety, as well as contributing to efficiency. For example, standardising medical supplies has enabled staff to rationalise their knowledge of the application of a wide variety of similar supplies, thereby assisting to improve error-free use. Standardising medical supplies also improves purchasing power.

Care pathways and clinical guidelines are examples of standardisation of the production processes (‘the work’) (see Claridge & Cook, Chapter 4). Recent initiatives, such as the UK National Health Service’s (NHS) Map of Medicine, employ process management techniques, almost by stealth, to introduce greater standardisation in the craft-process relationship between clinician and patient. However, doctors relish their individual independence and reject standarisation of care (Degeling et al 2001). Thus, while there is evidence that the standardisation offered through pathways and guidelines improves quality of care (Caminiti et al 2005, Vikoren et al 2006) there has been mixed success in implementation and consistent use, with recent studies identifying substantial barriers. Within healthcare, the difficulties in standardising work reflect the

… insoluble paradox between the need for consistent and evidence-based standards of care and the unique predicament, context, priorities, and choices of the individual patient.

(Plsek & Greenhalgh 2001:627)

This paradox distinguishes health service management from management in other industries, as health is characterised by:

▪ complex decision making at the patient care level that is negotiated between the patient and healthcare professional

▪ serious consequences of errors in decision making that may result in death or injury

▪ an uncertain external environment, with the combination of public and private financing and delivery schemes making it difficult to navigate

▪ goals of service delivery, which are often ambiguous and potentially conflicting (Leatt & Porter 2003).

While these factors might suggest that healthcare by definition will have high variation, studies consistently confirm that the variation caused by the organisation of the delivery system outweighs the variation caused by the random arrivals of patients with their ‘unique’ needs (Haraden & Resar 2004). The need to balance standards of care with patient individuality may also explain the fact that in comparison with other industries, there has been little emphasis on standardisation of outputs in healthcare (Glouberman & Mintzberg 2001b). The reduction in anaesthesia deaths in the US from rates of 25 to 50 deaths per million in the 1970s and 1980s (Ross & Tinker 1994) to current rates of less than 5 per million (Eichhorn 1989) and the development of diagnosis-related groups are two examples of the standardisation of outputs, although it is difficult to find others.

Operations management – the obstacles in healthcare

Three hypotheses are proposed to explain why operations management has not permeated the healthcare industry and are discussed further below:

1. the influence of craft production in a mass production environment

2. the difficulties in applying production management concepts to services

3. the emphasis on inputs in public administration.

The influence of craft production in a mass production environment

Healthcare has tended to be craft-based production – a trained healthcare professional provides his or her craft for individual patients, with little need for management. But as healthcare has moved from service delivery primarily in the community (that is, in the patient’s home or the doctor’s local surgery) to institutions such as hospitals, aspects of mass production have been introduced.

The organisation and operation of the hospital illustrates the difficulties transferring craft production to a setting that requires teamwork, coordination and integrated production. Hospitals display a fundamental inconsistency in that they are organised in formal managerial and clinical hierarchies that are based on scientific management principles, yet they try to maintain a commitment to professional autonomy for clinicians (Leggat & Dwyer 2005). The complex multifaceted production processes in hospitals are managed with a craft production mentality. This has resulted in an emphasis on managing (through the hierarchies) those aspects of operations that don’t interfere with the craft production relationship between clinician and patient. This was demonstrated by a review of management decisions in the NHS which found little managerial control over medicine (Harrison & Lim 2003), and by an Australian study that found that clinician managers focused on financial management, people management, organisational management and customer orientation (Braithwaite 2004). Clinical management was not identified as a primary pursuit of this group of managers. Instead, process, quality and data management – key components of clinical management – were only found in the secondary pursuits, where the clinician managers reported spending less time and effort (Braithwaite 2004). A more recent study of Australian public health managers found similar results (Braithwaite et al 2007).

Avoiding management of the clinician–patient relationship has resulted in independent, and largely inefficient, craft production. Instead of an effective interdisciplinary care delivery model, hospital organisation and hierarchy reinforces parallel care processes that only occasionally intersect. In addition, the healthcare professions have differing views on the evidence for effective practice, and the education, training and work practices of our health workers provide limited opportunities for the multidisciplinary evidence sharing and debate necessary to achieve consensus on clinical processes (Dopson et al 2002). When care is delivered through multiple clinical processes that are based on different clinical evidence and that only occasionally intersect, management of the processes to achieve efficient, consistent and high-quality care is difficult.

The healthcare craft production model depends on the staff involved to deliver error-free service. Quality control is largely focused on post-process audit. Other industries have realised that human beings cannot consistently maintain the required high performance levels and therefore create systems to reduce variation within processes. These systems anticipate and compensate for the likely errors that normal humans make (Resar 2006).

Pause for reflection

Why do healthcare managers in many countries struggle to find an appropriate operating structure that can influence service quality in a craft production environment? Why, as a result, is the healthcare industry characterised by a tension between craft production and mass production operation and quality control principles?

The difficulties in applying production management concepts to services

Services and products are different. Because operations management has evolved from production processes it has taken time to see how the concepts might translate to service provision, such as healthcare. While General Electric (GE) was able to quickly use a six sigma strategy to set reliability goals for manufactured products, it took much longer to apply the same concepts to the GE service-oriented businesses. Unlike manufacturing, service production and consumption take place simultaneously with high customer interaction, but the operations management concepts are the same. For example, while production control in other industries is concerned with the movement of materials, in healthcare the flows of the patients are critical to the process (Vissers & Beech 2005).

Evidence from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement suggests that improving patient flow can enhance clinical outcomes, address patient safety, increase patient and staff satisfaction and reduce operating costs (Haraden & Resar 2004). Yet application of process management to improve patient flow (from the perspective of both the patient and the providers) has been difficult, as no one has responsibility for the patient throughout their entire journey. As described by Glouberman & Mintzberg, within a hospital the medical staff tend to have discrete interventional relationships with patients, while the nursing and allied health staff play a more continuous part in the production process (Glouberman & Mintzberg 2001a). However, the nurses and allied health practitioners ‘are functionally subordinate to the physicians’ (Glouberman & Mintzberg 2001a:61) and are therefore unable to exert much control over the patient care processes.

Further, while manufacturers can provide detailed specifications of products, services have intangible outputs, with quality often perceived differently by different consumers. In healthcare, the outputs are often not fully known, are subjective and vague (Vissers & Beech 2005), and quality is difficult to measure (Peabody et al 2000). This leads to the next issue – inputs are much easier to measure, analyse and control than the service outputs or outcomes.

The emphasis on inputs in public administration

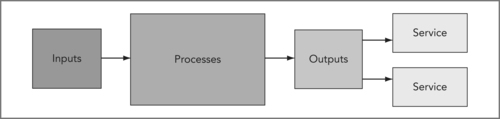

In both product and service systems, inputs (such as raw materials) are transformed through a process to outputs (such as services) as shown in Figure 2.1. Because the clinical outputs and outcomes are difficult to specify in healthcare, we have traditionally focused on measuring, monitoring and improving inputs. Policymakers and managers have largely been concerned with the number of patients accessing services and costs of the staff and facilities mobilised to provide the services. Despite the assertion that ‘no provider should be allowed to practice medicine without measuring and reporting results’ (Davidson & Randall 2006:49), in many jurisdictions the funders of public healthcare services require performance reporting on inputs and not clinical outcomes. For example, a study on performance indicators in the Victorian public health sector found an overemphasis on financial and volume indicators at the expense of indicators of the outcomes of the clinical processes (Leggat et al 2005). The financial inputs (the costs) tend to be the easiest to measure. Because the outputs (the benefits) are difficult to define and measure ‘analysts race around cutting the costs with no measurable effect on the benefits’ (Glouberman & Mintzberg 2001b:74).

|

| Figure 2.1 |

As discussed above, the healthcare service system is characterised by parallel care processes with sturdy walls between health professional disciplines, between service components and between organisations. One reason these boundaries have been allowed to develop is that health service performance indicators have traditionally focused on an individual service. Clinicians receive feedback on their part of the process. The underdeveloped information systems and lack of clear ownership of the end-to-end clinical process have made it difficult to track the throughputs and outputs of the care process as a whole. In most healthcare organisations the budgets and resulting reporting structures are departmentally organised. Traditional financial indicators were devised from cost accounting systems designed for an environment of mass production of a few standardised items, and not for the complexity of the healthcare processes and outcomes. The information systems supporting these indicators are optimised for managing transactions within departmental ‘silos’. This means that few healthcare organisations have information systems that can effectively track care processes from beginning to end (Leggat et al 2005) and while clinicians appear to accept standardisation when they are provided with objective measures to review their performance, the existing measures perpetuate the system boundaries.

Although there is growing evidence of the effectiveness of information management in improving hospital care (Committee on Quality of Healthcare in America 2001, Institute of Medicine 2000), hospitals and health service organisations are judged to be at least 10 years behind in information investment in comparison with organisations in other industries of comparable size and complexity (Ferlie & Shortell 2001). At present there are few health organisations with information systems that can effectively link and integrate financial and clinical data and the information base to support evidence-based practice is quite limited (Kane & Mosser 2007). Ferlie & Shortell (2001:297) argue that information technology represents a ‘powerful untapped force for changes that can improve the quality of care’. Berg (2005) suggests that information technology implementation is often only considered a technical project, and that this results in limited ability to access the information required to understand and improve processes (Berg et al 2005). The healthcare industry is only just realising the information that is required to understand and manage clinical processes. Hence, it will be some time before the process and outcome data that are used effectively in operations management in other industries are readily available in public healthcare.

Pause for reflection

Process and operations management are well-supported management disciplines that have been shown to improve efficiency and effectiveness in many industries. Aspects of operations management are visible in healthcare organisations, but there has been little application to the clinical care processes. Why is the craft production mode in healthcare hypothesised to constrain clinical process management? How are specialisation and standardisation applicable to the inputs, processes and outputs of healthcare delivery? What data are required to increase our understanding of clinical processes?

Operations management – value for healthcare

As discussed in Chapter 1, over the past decade healthcare has been perceived as an increasing financial burden, with less than the expected impact on improving population health. Consumers expect higher quality services, more information about treatment options that enable full participation in treatment decisions, and more visible accountability for the operation and outcomes of their health services. Stephen Duckett wrote in 1994 that, with the advent of casemix, Australian healthcare had entered a new era of accountability (Duckett 1994). Yet we continue to see public and professional concerns about the quality of care, and the healthcare sector has been under increasing scrutiny, with a strong push to improve the responsiveness, quality and safety of the services provided. In this search for value, there is increasing realisation that health system management must move beyond the existing emphasis on managing the inputs, to more effective management of the processes and the outputs. Improving outcomes requires management of those processes that transform the health system inputs.

Clinical, administrative and ancillary processes are used to deliver healthcare services. Clinical processes focus on the planning, design, delivery and control of the steps necessary to provide a service for a healthcare consumer (Vissers & Beech 2005). Management processes support the clinical processes, while the ancillary processes support the general functioning of the organisation, comprising functions such as cleaning and maintenance. Processes have been described as ‘invisible economic assets and liabilities’ (Keen & Knapp 1996), suggesting that a focus on effective process management is of financial benefit to the organisation.

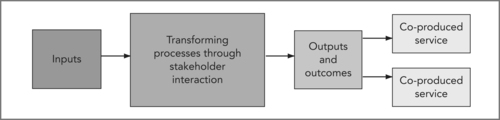

One of the reasons that operations management has been effective in improving the production of products and services is the understanding of the customer that its principles and practices require. Michael Hammer, a strong proponent of business process re-engineering, originally considered a process to be solely the conversion of input to outputs. However, more recently, in partnership with Grady, Hammer suggested that a process was not just this transformation, but also included the stakeholders who interacted to achieve the desired results (Nwabueze 2000). This approach to understanding processes is critical in healthcare – the nature of the industry and its consumers and workforce must drive clinical process management as shown in Figure 2.2.

|

| Figure 2.2 |

In healthcare delivery there are two principal customer groups that need to be included in the management of clinical processes: the consumers of healthcare (the patients, clients and their families) and the individuals who bring their craft to the hospital, home or community health centre (the health professionals). There is substantial evidence that improving the operations and outcomes of the healthcare system requires a consumer focus and high staff involvement (Committee on Quality of Healthcare in America 2001).

Consumer-focused care

Healthcare systems have been typically organised around the values of clinicians (Committee on Quality of Healthcare in America 2001), but recent evidence stresses that understanding how healthcare works for patients is essential to improving clinical outcomes (Batalden 1998, Committee on Quality of Healthcare in America 2001, Nicholson 1995). Advocates for applying operations management techniques in healthcare stress that enhancing the healthcare system requires an understanding of value that can only be defined by the customer (Womack & Jones 2003). While there is strong rhetoric around reorientation to a patient or consumer focus in most healthcare systems, healthcare professionals have yet to fully embrace consumer values. One has only to attend an emergency or outpatient department to see processes organised for health professionals and not for patients and families.

A 2006 literature review of hospital process improvement studies published between 1989 and 2004 found that the promise of 7428 titles and abstracts only resulted in 88 articles describing 86 process improvement studies in hospital care that had a robust method and sufficient information to evaluate the intervention (Elkhuizen et al 2006). The important finding of this review was that the studies were predominantly focused on cost reduction and resource utilisation; parameters related to the patient experience and patient values were rarely used (Elkhuizen et al 2006). This is consistent with the evolution of process management within other industries. A review of 33 organisations from seven industries with process re-engineering experience found that as organisations matured in process management, the focus shifted from an emphasis only on improving costs, to more strategic and consumer-focused aims of improving service delivery (Maull et al 2003). More recent operations management initiatives, such as lean thinking, have further progressed the focus on understanding and responding to consumer value (Hines et al 2004).

Because of the complexities of the healthcare system, many process activities have focused on a ward, unit or department. The organisation of the workforce has led to fragmentation of healthcare processes (Leggat 2007), and while patients travel through the system, it is difficult to examine the processes across the system. While there may be local successes in improving processes, these often lead to problems elsewhere in the organisation or broader system. The evidence is unequivocal that single-process projects are not as effective as a strategic system approach (Balle & Regnier 2007, Nwabueze 2000). Yet the complexity, visibility and high levels of regulation of the healthcare system make attempts at change more difficult than in other industries (Berwick 2002).

Further, societies are fiercely protective and have strong expectations for their healthcare systems. The media play a strong role in public debate and opinion about healthcare, often with direct impact on the careers of health professionals and politicians. These factors push for small-scale incremental changes, at the expense of the necessary strategic systemic approach. Drawing from the experience of other industries, key drivers of improved performance in quality and safety include an orientation to customer satisfaction that is supported throughout the organisation, an organisational configuration that ensures seamless interaction by the consumer, and information about customer relationships (Day 2004). Yet, there is strong evidence that patient involvement in the healthcare system ‘is, in reality, constrained by organisational, clinical or economic factors’ (Salmon & Hall 2004:53). A strong focus of operations management is the definition of customer value. The healthcare sector needs to increase understanding of customer value and incorporate it into the management of clinical processes to facilitate achievement of consumer-focused policy objectives.

Pause for reflection

Although characterised as having a primary focus on the operations of a business or organisation, a key aspect of operations management is the development of a strong understanding of customer value that is meant to influence all operating decisions. Why might this be so?

Fostering high commitment

Everything points to one central fact: Clinical activities cannot be coordinated by managerial interventions— not by outside bosses or coordinators, not by administrative systems, not by discussions of ‘quality’ disconnected from the delivery of it, not by all that constant reorganizing.

The message has been consistent that clinicians need to be involved in managing clinical processes. Donald Berwick stressed that clinical operations needed to be effected by the ‘managed’, not by the managers (Berwick 1994), and there is increasing evidence that successful clinical process management is based on clinicians adopting a leadership role and championing the process (Hyett et al 2007) (see Stanton, Chapter 3; Warburton, Chapter 9; and Berding, Resources).

While essential, motivating clinicians has not been easy as the ‘old boys’ medical networks have largely made process control unworkable (Braithwaite 2004). While it is thought that clinicians should welcome any assistance that improves clinical care processes, professional autonomy continues to create barriers to clinical process management (Degeling et al 2001, Panella et al 2003). In addition, the different cultures that exist among the specialised health professional groups makes it difficult to find an approach to involvement that satisfies all (Degeling et al 2001). This has led to the suggestion that health professional education must move from the current content-oriented learning to process-oriented learning methods (Fraser & Greenhalgh 2001). If there is an expectation that clinicians and managers will manage clinical processes there is a need to ensure training in processes.

Finally, process management must be supported by integrated performance management (Maull et al 2003). Currently the health sector does not hold care teams accountable for achieving outcomes that are valued by consumers. For example, ancient Chinese palace doctors could be put to death if the emperor died. This resulted in very clear performance expectations with direct linking of expected outcomes and rewards. Although the airline and healthcare industries are often compared as complicated high-risk industries, the fact that pilots can lose their life in a plane crash (which also sets up clear performance expectations for pilots) is often jokingly cited as a major difference between the two industries. It has been suggested that the airline industry has demonstrated better success in process enhancement to improve customer quality and safety than the healthcare industry.

There is considerable general evidence to support effective performance management in improving organisational outcomes (Huselid 1995), and there is specific evidence relating performance appraisal to better clinical outcomes (West et al 2002). However there is much to be done to improve performance monitoring and management in healthcare (Bartram et al 2007, Leggat et al 2005, Leggat & Dwyer 2005). Process and performance are inextricably linked through operations management. Use of operations management to improve the management of clinical processes, by definition, requires establishing performance management expectations for providers that are responsive to consumer values.

Pause for reflection

How could operations management be used to encourage greater clinician participation in managing clinical processes? What operations management principles are particularly relevant?

Conclusion

The health sector has been slower than other industries to embrace operations management. The traditional organisation, production modes, availability of information and performance monitoring in healthcare have created considerable obstacles to effective operations management. Recognising that healthcare delivery processes may be defective a large proportion of the time has led to consideration of the applicability of tools and techniques from other industries, with the conclusion that health system improvements will only be achieved with a refocusing from the management of system inputs to effective management of clinical processes and resulting outputs – that is, operations management.

References

Balle, M.; Regnier, A., Lean as a learning system in a hospital ward, Leadership in Health Services 20 (2007) 33–41.

Bartram, T.; Stanton, P.; Leggat, S.G.; et al., Lost in translation: making the link between HRM and performance in healthcare, Human Resource Management Journal 17 (2007) 21–41.

Batalden, P., Collaboration in improving care for patients: how can we find out what we haven’t been able to figure out yet?Journal of Quality Improvement 24 (1998) 609–618.

Ben-Tovim, D.I.; Bassham, J.E.; Bolch, D.; et al., Lean thinking across a hospital: redesigning care at the Flinders Medical Centre, Australian Health Review 31 (2007) 10–115.

Berg, M.; Schellekens, W.; Bergeni, C., Bridging the quality chasm: integrating professional and organizational approaches to quality, International Journal for Quality in Healthcare 17 (2005) 75–82.

Berwick, D.M., Eleven worthy aims for clinical leadership of healthcare reform, Journal of the American Medical Association 272 (1994) 797–802.

Berwick, D.M., A user’s manual for the IOMs ‘Quality Chasm’ report, Health Affairs 21 (2002) 80.

Bowen, D.E.; Youngdahl, W.E., ‘Lean’ service: in defense of a production-line approach, International Journal of Service Industry Management 9 (3) (1998) 207–225.

Braithwaite, J., An empirically-based model for clinician-managers’ behavioural routines, Journal of Health Organization and Management Decision 18 (2004) 240–261.

Braithwaite, J.; Luft, S.; Bender, W.; et al., The hierarchy of work pursuits of public health managers, Health Services Management Research 20 (2007) 71–83.

Buck, C.R.J., Healthcare through a six sigma lens, The Milbank Quarterly 76 (1998) 749–753.

Caminiti, C.; Scoditti, U.; Diodati, F.; et al., How to promote, improve and test adherence to scientific evidence in clinical practice, BMC Health Services Research 19 (2005) 62.

Davidson, A.; Randall, R.M., Michael Porter and Elizabeth Teisberg on redefining value in healthcare: an interview, Strategy & Leadership 34 (2006) 48–50.

Degeling, P.; Kennedy, J.; Hill, M., Mediating the cultural boundaries between medicine, nursing and management – the central challenge in hospital reform, Health Services Management Research 14 (2001) 36–48.

Dingwall, R.; Rafferty, A.M.; Webster, C., An Introduction to the Social History of Nursing. (1988) Routledge, London.

Dopson, S.; Fitzgerald, L.; Ferlie, E.B.; et al., No magic targets! Changing clinical practice to become more evidence based, Health Care Management Review, Special Issue 27 (2002) 35–47.

Duckett, S.J., Hospital and departmental management in the era of accountability: addressing the new management challenges, Australian Health Review 17 (1994) 116–131.

Edmondson, A., Learning from mistakes is easier said than done: group and organizational influences on the detection and correction of human error, Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 32 (1996) 5–28.

Eichhorn, J.H., Prevention of intraoperative anesthesia accidents and related severe injury through safety monitoring, Anesthesiology 70 (1989) 572–577.

Elkhuizen, S.G.; Limburg, M.; Bakker, P.J.M.; et al., Evidence-based re-engineering: re-engineering the evidence, International Journal of Healthcare Quality Assurance 19 (2006) 477–499.

Ferlie, E.B.; Shortell, S.M., Improving the quality of healthcare in the United Kingdom and the United States: A framework for change, The Milbank Quarterly 79 (2001) 281–315.

Fraser, S.W.; Greenhalgh, T., Coping with complexity: educating for capability, British Medical Journal 323 (2001) 799–803.

Haraden, C.; Resar, R., Patient flow in hospitals: understanding and controlling it better, Frontiers of Health Services Management 20 (2004) 3–15.

Harrison, S.; Lim, J.N.W., The frontier of control: doctors and managers in the NHS 1966 to 1997, Clinical Governance: An International Journal 8 (2003) 13–18.

Hines, P.; Holwe, M.; Rich, N., Learning to evolve: a review of contemporary lean thinking, International Journal of Operations & Production Management 24 (2004) 994–1012.

Huselid, M., The impact of human resource management practices on turnover, productivity and corporate financial performance, Academy of Management Journal 38 (1995) 635–672.

Institute of Medicine, To Err is Human: Building a Safer Healthcare System. (2000) National Academy Press, Washington.

Kane, R.L.; Mosser, G., The challenge of explaining why quality improvement has not done better, International Journal for Quality in Healthcare 19 (2007) 8–10.

Keen, P.G.; Knapp, E.M., Every Manager’s Guide to Business Processes. (1996) Harvard Business School Press, Boston.

Kelly, A.-M.; Bryant, M.; Cox, L.; Jolley, D., Improving emergency department efficiency by patient streaming to outcomes-based teams, Australian Health Review 31 (2007) 16–21.

Leatt, P.; Porter, J., Where are the healthcare leaders? The need for investment in leadership development, Healthcare Papers 4 (2003) 14–31.

Leggat, S.G.; Bartram, T.; Stanton, P., Performance monitoring in the Victorian healthcare system: an exploratory study, Australian Health Review 29 (2005) 17–24.

Leggat, S.G.; Dwyer, J., Improving hospital performance: culture change is not the answer, Healthcare Quarterly 8 (2005) 60–66.

Leung, G.M., Hospitals must become ‘focused factories’, British Medical Journal 320 (1999) 942.

Maull, R.S.; Tranfield, D.R.; Maull, W., Factors characterising the maturity of BOR programmes, International Journal of Operations and Production Management 23 (2003) 596–624.

Mintzberg, H., Managing care and cure – up and down, in and out, Health Services Management Research 15 (2002) 193–206.

Nicholson, J., Patient focused care and its role in hospital process re-engineering, International Journal of Healthcare Quality Assurance 8 (1995) 23–26.

Nwabueze, U., In and out of vogue: the case of BPR in the NHS, Managerial Accounting Journal 15 (2000) 459–463.

Panella, M.; Marchisio, S.; Di Stansilao, F., Reducing clinical variations with clinical pathways: do pathways work?International Journal for Quality in Healthcare 15 (2003) 509–521.

Peabody, J.W.; Luck, J.; Glassman, P.; et al., Comparison of Vignettes, Standardized Patients, and Chart Abstraction, Journal of the American Medical Association 283 (2000) 1715–1722.

Plsek, P.E.; Greenhalgh, T., Complexity science. The challenge of complexity in healthcare, British Medical Journal 323 (2001) 625–628.

Ramanujami, R.; Rousseau, D.M., The challenges are organizational not just clinical, Journal of Organizational Behavior 27 (2006) 811–827.

Resar, R., Making noncatastrophic healthcare processes reliable: learning to walk before running in creating high-reliability organizations, Health Services Research 41 (2006) 1677–1689.

Ross, A.F.; Tinker, J.H., Anesthesia risk, In: (Editor: Miller, R.D.) Anesthesia4th ed. (1994) Churchill-Livingston, New York.

Runciman, W.B.; Williamson, J.A.H.; Deakin, A.; et al., An integrated framework for safety, quality and risk management: an information and incident management system based on a universal patient safety classification, Quality and Safety in Healthcare 15 (2006) 82–90.

Salmon, P.; Hall, G.M., Patient empowerment or the emperor’s new clothes, Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 97 (2004) 53–56.

Savitz, L.A., Assessing the implementation of clinical process innovations: a cross-case comparison, Journal of Healthcare Management 45 (2000) 366–379.

Scott, I.A.; Denaro, C.P.; Bennett, C.J., Achieving better in-hospital and after-hospital care of patients with acute cardiac disease, Medical Journal of Australia 180 (2004) S83–S88.

Vikoren, T.H.; Musser, R.C.; Tcheng, J.E.; et al., From clinical pathways to CPOE: challenges and opportunities in standardization and computerization of postoperative orders for total joint replacement, Journal of Surgical Advances 15 (2006) 195–200.

Vissers, J.; Beech, R., Health Operations Management. Patient Flow Logistics in Healthcare. (2005) Routledge, London.

Walston, S.L.; Burns, L.R.; Kimberley, J.R., Does reengineering really work? An examination of the context and outcomes of hospital reengineering initiatives, Health Services Research 34 (2000) 1363–1388.

West, M.A.; Borrill, C.; Dawson, J.F.; et al., The link between the management of employees and patient mortality in acute hospitals, International Journal of Human Resource Management 13 (2002) 1299–1310.

Womack, J.P.; Jones, D.T., Lean Thinking. (2003) Simon & Schuster, London.