Chapter 44 Operations for Vascular Compressive Syndromes

In recent years, microvascular decompression (MVD) has become the operative treatment of choice for many disorders of the cranial nerves, augmenting and replacing ablative procedures. These cranial rhizopathies have long defied categorization, clarification of pathophysiology, and definitive treatment despite efforts by clinicians in several disciplines. Although the clinical presentations of disorders such as trigeminal neuralgia, hemifacial spasm, glossopharyngeal neuralgia, tinnitus, spasmodic torticollis, disabling positional vertigo, and Meniere’s disease are quite different, these problems all share a common underlying pathology: vascular compression of the respective cranial nerve in the proximal nonfascicular region. Several studies have shown improved blood pressure control in medically refractory, severely hypertensive patients after MVD of the left lateral medulla oblongata.1,2

Beginning in 1966, a patient with trigeminal neuralgia was noted at operation to have compression of the trigeminal nerve by a small artery near the brainstem.3 The same year, a patient with hemifacial spasm was cured after coagulation of a vein that was distorting the facial nerve at the brainstem. As we performed operations to relieve vascular compression of the trigeminal and facial nerves, it became apparent that pulsatile, mechanical forces from a blood vessel were the pathophysiologic mechanism responsible for these cranial hyperactive syndromes. These syndromes later included glossopharyngeal neuralgia, tinnitus, and vertigo. All the cranial nerves are subject to the forces of vascular compression with arteriosclerosis, elongation, and brain sag as operant factors. This chapter describes the patient selection criteria, operative technique, perioperative management, results, and complications after more than 8000 MVDs for the aforementioned cranial rhizopathies.

PREOPERATIVE EVALUATION

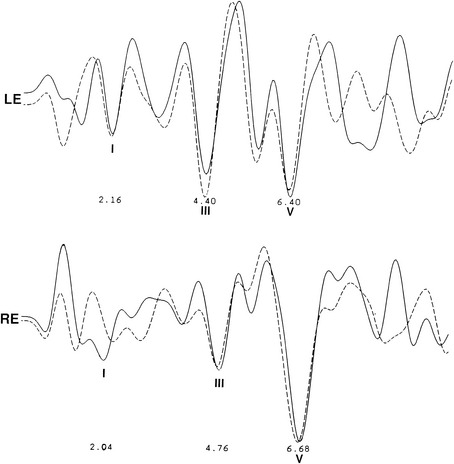

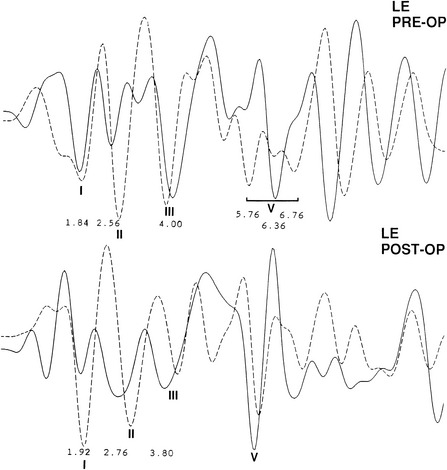

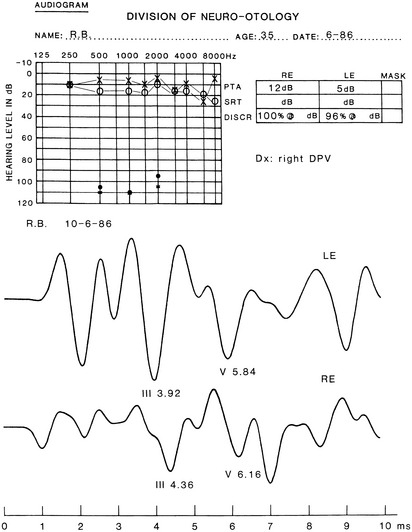

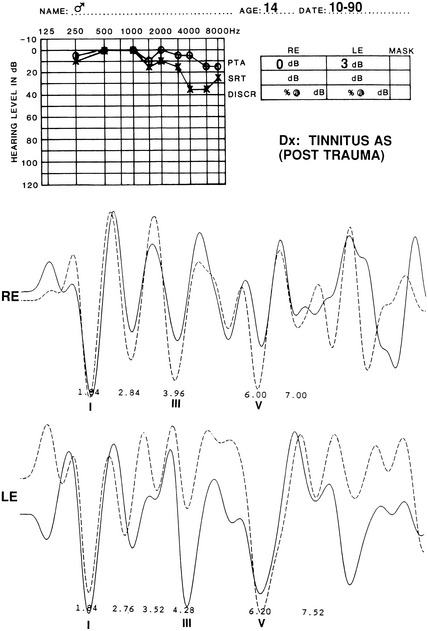

The audiometric tests are performed preoperatively to obtain a baseline for quantitatively determining deteriorations or improvement in hearing function. The pure tone audiogram often shows anomalies represented by small dips in the frequency range of 1500 to 2000 Hz.4 Additionally, preoperative BAEPs provide baseline information for the clinical neurophysiology team so that they may warn the surgeon of any deviations during monitoring of the intraoperative auditory evoked potentials. Typical changes observed in the BAEP are an increased interpeak latency between peaks I and III ipsilaterally or prolongation of interpeak latency between III and V contralaterally (Figs. 44-1 to 44-4). These findings are based on our knowledge of the neural generators of BAEPs.5–8

TRIGEMINAL NEURALGIA

Patient Selection

Patients with trigeminal neuralgia refractory to medical management are selected for MVD on the basis of their symptoms, history, and ability to undergo a general anesthetic. Patients with contraindications to general anesthetics or intracranial procedures may be treated with ablation procedures, including percutaneous glycerol rhizotomy, percutaneous radiofrequency rhizotomy, trigeminal balloon microcompression, stereotactic radiosurgery, and peripheral neurectomy.9,10 A discussion of these other surgical techniques is imperative for understanding why surgeons in many centers consider MVD to be the operative procedure of choice for most patients.

Peripheral neurectomy, although less invasive, typically has a short duration of tic relief, and may be indicated for patients with a shortened life expectancy.11 Radiofrequency lesions, created by percutaneous passage of a needle into the gasserian ganglion, have an initial success rate of 90% or greater, with long-term pain relief ranging from 20% to 78% of patients.12–15 Approximately 20% of patients have facial dysesthesias after radiofrequency rhizotomy. The greater the sensory loss, the more likely the trigeminal neuralgia will be relieved, but it is also more likely that dysesthesias leading to frank anesthesia dolorosa will supervene. Percutaneous glycerol rhizotomy rarely causes facial dysesthesias or sensory loss when performed strictly according to the technique introduced by Hakanson in 1981.16 Although glycerol rhizotomies have initial success rates of 80% to 90%,17 median time to recurrence varies from 16 to 36 months.18–21 Balloon microcompression of the trigeminal ganglion has initial pain relief ranging from 78% to 100%,17,22 with mean time to recurrence of 3.5 years.23 Minor dysesthesias occur in approximately 20% of patients,23 and mild temporary masseter weakness is seen in most patients treated with balloon microcompression.22 The corneal reflex is usually present.

Patients who have undergone radiofrequency lesions and balloon compression are initially satisfied because the trigeminal neuralgia is gone, but the side effects of numbness gradually become bothersome. In large series, new or worsening numbness or paresthesias after stereotactic radiosurgery (i.e., Gamma Knife) for trigeminal neuralgia occurred in 10%,24 10%,25 and 19%26 of patients, and complete pain relief (without medication) was achieved in 40% (2-year median follow-up),24 48% (1-year follow-up),25 and 34% (3-year follow-up).26 Median time to response (achievement of at least 50% pain relief) after stereotactic radiosurgery was 60 days,24 10 days,25 and 24 days.26 In another series of patients undergoing repeat stereotactic radiosurgery for trigeminal neuralgia, the authors concluded that most patients (85%) achieved more than 50% pain relief. New or worsening paresthesias occurred in 13% of patients, however, and complete pain relief (without medication) was achieved in only 19% of patients.27

The choice between MVD and other procedures should be governed by patient preference and ability to tolerate a craniotomy under general anesthesia. Advantages of MVD include consistently higher long-term success rates with a minimal chance of facial sensory loss or dysesthesias. These advantages are quite substantial in that the average life expectancy of the patients treated by the authors was 32 years from the initial onset of symptoms.28

The classic symptom of typical trigeminal neuralgia is lancinating pain in one or more distributions of the trigeminal nerve. Talking, eating, shaving, and feeling the wind blowing often precipitate symptoms. Patients typically have an abrupt and memorable onset of symptoms, with a variable duration of remission. A burning, aching pain without specific trigger points characterizes atypical trigeminal neuralgia,29 in contrast to typical trigeminal neuralgia. Although surgical success with these patients is less than with patients with typical symptoms, no other reasonable alternative treatments currently exist. Many patients have initial success with medical management using agents such carbamazepine, phenytoin, baclofen, valproic acid, clonazepam, and gabapentin. Carbamazepine historically has been most effective, but only 56% of patients maintain satisfactory pain relief after 10 years.30 Often, side effects, allergies, and the development of refractory symptoms to medications necessitate the need for early surgical intervention.

Operative Technique for Microvascular Trigeminal Decompression

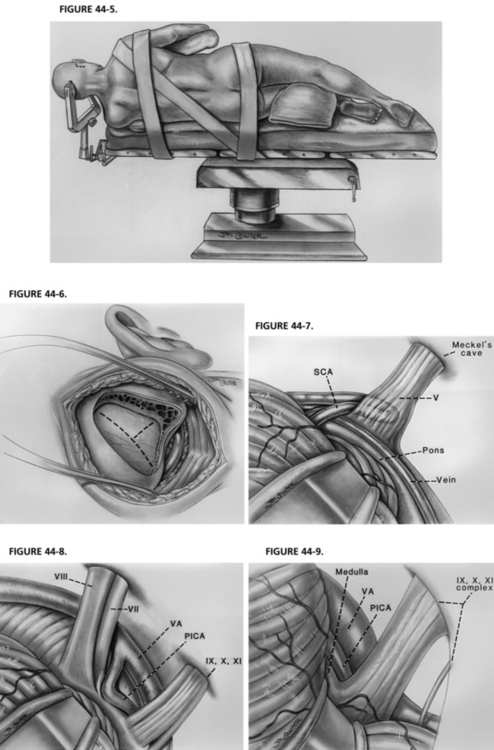

As in any operation, patient positioning is important. The patient is placed on the operating table with the head at the foot of the bed, providing maximal room for the surgeon during the microscopic portion of the case. A three-point head holder is applied and the patient is placed in the lateral decubitus position. An axillary roll and padding to other pressure points are placed. The neck is minimally put on stretch and slightly flexed, always maintaining at least two fingerbreadths between the patient’s chin and sternum. The patient is secured to the bed using straps and adhesive tape across the hips. The head holder is fastened into position. The patient’s shoulder is taped caudally for maximal working room (Fig. 44-5).31,32

After satisfactory positioning, a 2 cm strip of hair behind the ear is shaved and prepared. The incision, approximately 3 to 5 cm long (longer in a large man, shorter in a small woman), is placed 0.5 cm posterior to the hairline, extending one fourth above the iniomeatal line and three fourths below.31,32 Electrocautery is used to dissect and clear soft tissue until the mastoid eminence is adequately visualized.

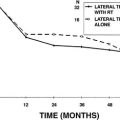

Before beginning the craniectomy, the digastric groove should be visualized (5 cm behind the ear canal [4 cm in women] and 1 cm caudal to the lateral canthus, external ear canal line). The mastoid emissary vein, which is a good landmark for the junction between the sigmoid and transverse sinuses, may bleed. It should be waxed. The craniectomy is expanded until the junction of the transverse and sigmoid sinuses is definitively appreciated, with the apex of the triangular craniectomy pointed at this junction (variations are discussed with other cranial nerve syndromes) (Fig. 44-6). All air cells are waxed diligently, after which a curvilinear or T-shaped durotomy is performed, exposing a direct corridor along the petrotentorial bone down to the brainstem.31,32

When the dura is sutured back, the operating microscope is used to “turn the corner,” or expose the cerebellopontine angle. While gently retracting on the cerebellum with a Cottonoid on a sterile piece of latex (rubber dam), the surgeon must allow adequate cerebrospinal fluid to drain so that the cerebellum falls away, minimizing the need for much cerebellar retraction. Penetration of the trigeminal cistern and sharp dissection of arachnoid adhesions greatly reduce the need for significant cerebellar retraction medially. The Cottonoid and a precisely flexible, self-retaining brain retractor are placed on the supralateral portion of the cerebellum for trigeminal exposures. The cerebellum is retracted up and medially. Often, the first vessels encountered are the petrosal vein complex, which are coagulated and divided after evaluating relationships to the nerve.31,32

Before performing MVD of the trigeminal nerve, the surgeon must be aware that the dorsal root exit zone of the trigeminal nerve (the junctional area of myelin) extends to the distal portion of the nerve. The nerve must be meticulously inspected from the brainstem to Meckel’s cave, and all offending vessels must be decompressed. When performing the actual decompression, all arachnoid over the nerve must be dissected away. Shredded polytef (Teflon®) felt is placed between the vessel and the nerve. The most frequent vessel found is the superior cerebellar artery. Often multiple pieces of shredded Teflon felt are used to decompress looping arteries affecting more than one side of the trigeminal nerve.31,32

Results for Trigeminal Microvascular Decompression

The most frequent operative finding was trigeminal compression by the superior cerebellar artery in 76% of the patients (Fig. 44-7). Veins were causing neural compression in 68% of patients, but were the sole offending vessel in only 13%.38,39 In a report38 of 1204 patients who underwent initial MVD, 80% were pain-free at 1 year, and an additional 8% had greater than 75% relief, for a total success rate of 88%.38 At 10 years, 70% remained pain-free, and 4% had greater than 75% relief. Persistent mild postoperative facial numbness was noted in 17%, of which only 1% was severe. Repeat MVD was performed in 11% of patients for persistent or recurrent pain.38 Of these, 96% were pain-free or had greater than 75% pain relief 1 year after surgery (89% at 10 years).

MVD for pediatric-onset trigeminal neuralgia has a lower success rate than MVD for adults. At the time of discharge, 73% of patients had complete pain relief, with an additional 18% having greater than 75% diminution of pain.40 At last follow-up (mean 105 months), 57% of patients had either complete pain relief or greater than 75% relief of pain. The lower therapeutic response is likely due to the fact that the pathophysiology of the disease is different in pediatric patients. Venous compression was noted in 86% of the cases and was the sole offending vessel in 48%; this is markedly greater than for the adult patients. Additionally, venous compression often results in recurrence of pain because of revascularization. In 393 cases of trigeminal neuralgia caused by veins, 31% developed recurrence (most within 1 year of initial operation) after initial improvement of pain.

The morbidity and mortality with MVD for trigeminal neuralgia in elderly patients are similar to morbidity and mortality in younger patients in properly selected patients.37 We do not exclude patients from MVD by age alone. Each patient’s fitness for surgery is evaluated by a medical team, and we typically offer a percutaneous procedure to patients with contraindications to any surgery (e.g., severe lung [emphysema] and heart [congestive heart failure] disease). Other series33–36 comparing MVD in elderly patients and young patients have reached a similar conclusion that, with proper patient selection, MVD can be performed in elderly patients without causing higher postoperative morbidity and mortality. Although the “less invasive” procedures, with the exception of stereotactic radiosurgery, offer a comparably high rate of immediate pain relief, none can compare with the long-term success of MVD. In elderly patients, generalized atrophy and wide cisterns allow ease of access to the cerebellar pontine angle. We believe our findings support the notion that MVD should also be considered as the first-line procedure for trigeminal neuralgia in the elderly as it is in younger patients, and agree that age, by itself, should not be a barrier to MVD.37

Complications

In a review of our series by McLaughlin and colleagues,31 hearing loss was noted in 31 of 3196 patients after MVD for trigeminal neuralgia (0.97%).31 Before 1990, the incidence of hearing loss was 1.33%. Since 1990, that percentage has decreased to 0.59%.31 This decline in hearing loss is attributed to the use of brainstem auditory evoked response monitoring. The incidence of other complications is quite rare, with death occurring in 0.14% of cases.39

HEMIFACIAL SPASM

Patient Selection

Hemifacial spasm is more than simply a cosmetic problem. Although uncommon (prevalence of 7/100,000),41 it has significant psychosocial consequences, and may interfere with the patient’s ability to read, drive, or work. In children, hemifacial spasm may retard reading ability, causing significant and profound educational difficulties.42 In contrast to some disorders that may mimic hemifacial spasm, this disorder is characterized by paroxysmal contractions of the facial muscles on one side. The contraction typically begins around the orbicularis oculi muscles and progresses inferiorly to involve the lower portion of the face and the platysma. Approximately 15% of patients have frontalis involvement. Atypical hemifacial spasm differs from the more common form because contractions start in the buccal muscles and progress rostrally. The tonus phenomenon, or sustained contracture, is common in atypical and typical hemifacial spasm resulting in eye closure and ipsilateral abduction of the corner of the mouth. Response to MVD is similar between these two groups.

In contrast to patients with trigeminal neuralgia, patients with hemifacial spasm rarely receive temporary benefit from medications such as baclofen, carbamazepine, phenytoin, clonazepam, and other antianxiety medications.43,44 Botulinum toxin has been reported to be successful in 80% to 100% of treated patients.45–47 These benefits are transitory, with recurrence following in 12 to 16 weeks.45,46 Obvious facial weakness occurs in nearly 75% of patients treated with repeated injections for at least 3 years.48 A previous analysis showed that the mean life expectancy for patients with hemifacial spasm is 35 years from symptom onset.28 In such patients, botulinum toxin may be less cost-effective and potentially debilitating if given over such a protracted period. Botulinum toxin should not be used in the lower face. Surgery must not be performed within 9 months of botulinum toxin injection because intraoperative electromyography monitoring becomes useless.

Operative Technique for Microvascular Decompression in Hemifacial Spasm

MVD for hemifacial spasm is similar in several respects to MVD for trigeminal neuralgia. There are several important differences, however. As previously mentioned, the patient’s position is crucial for maximizing surgical success. For hemifacial spasm, the patient’s head is rotated away 10 degrees (as in trigeminal neuralgia), and the vertex is lowered 15 degrees toward the floor.31 This maneuver rotates the vestibulocochlear complex cephalad, while exposing the proximal portion of CN VII. Failure to tilt the vertex down may result in poor visualization of the facial nerve and failure to achieve adequate decompression. The patient is positioned and fixed in the standard lateral position.

A second important difference is that the patient must not be given muscle relaxants or paralytics because these interfere with intraoperative monitoring of electromyography potentials recorded from muscles innervated by CN VII. In patients with hemifacial spasm, stimulation of the temporal or zygomatic branch of the facial nerve electrically produces electromyography potentials in the mentalis muscle. This muscle response, specific for hemifacial spasm, has a latency of 10 ms.49 These abnormal electromyography recordings, known as lateral spread, disappear after decompression of the offending vessel.50 Failure to see disappearance of the lateral spread necessitates further inspection of the nerve by the surgical team.51

The skin incision and soft tissue dissection are the same for hemifacial spasm and trigeminal neuralgia. The bone work differs slightly in that more of the craniectomy extends inferiorly and laterally. The dura is opened in a curvilinear or T-shaped fashion and affixed with sutures. As cerebrospinal fluid drains, the operating microscope is employed, and the brain retractor is placed on the inferolateral portion of the cerebellum, elevating the cerebellum and the tonsils. Next, the cisterna magna is opened, sharply exposing CN IX, X, and XI, and, more superiorly, CN VII and VIII.31

Most commonly, a loop of the posterior inferior cerebellar artery is the offending vessel in typical hemifacial spasm (Fig. 44-8). The surgeon typically finds this loop anterior and caudal to the root entry zone. The posterior inferior cerebellar artery is found in 68% of patients, the anterior inferior cerebellar artery is found in 35%, and the vertebral artery is found in 24% (in some cases, multiple offending vessels were found).52 In atypical hemifacial spasm, the surgeon should look for the offending vessel rostrally or lying between CN VII and VIII. Failure to recognize one or all offending vessels is most common when attempting MVD of CN VII.

Results for Microvascular Decompression in Hemifacial Spasm

Many clinicians report high success rates with MVD for hemifacial spasm. Iwakuma and coworkers53 reported a 97% success rate after treating 74 patients. Auger and associates54 reported complete relief of spasm in 81% of their patients after nearly 4 years. In an analysis of 16 series, Loeser and Chen55 reported an 84% rate of complete spasm relief and an additional 4% relief after a second operation. In a review of the authors’ series, 86% had excellent relief of spasm, with an additional 5% claiming greater than 75% improvement in spasms.52 These results remained stable at 10-year follow-up. Of 12 patients without any improvement, 11 underwent repeat MVD, and 10 achieved excellent long-term results.52 We recommend that patients without any symptomatic improvement in the initial postoperative period undergo repeat exploration. For patients with even slight improvement in spasm, however, close follow-up is recommended because these patients tend to experience continued improvement.

The most common offending vessel in a series of 648 consecutive MVDs was the posterior inferior cerebellar artery, found in 68% of the cases. The anterior inferior cerebellar artery was compressing CN VII in 35% of the cases.52 The pathology for pediatric hemifacial spasm is quite different; venous compression (alone or with another artery) was noted in 75% of the pediatric cases.42 Because venous compression is known to recur after MVD, the rate of excellent outcomes is 67% (mean follow-up 125 months) in the pediatric population.42

Complications

In a series of 782 operations for hemifacial spasm, 3.2% of patients experienced transient facial weakness.52 In McLaughlin and colleagues’ report31 of 1069 operations by the senior author, the incidence of ipsilateral hearing loss was 2.99%. After 1990, when the use of intraoperative brainstem evoked potentials became routine, the incidence of hearing loss decreased to 1.59%.31 Cerebrospinal fluid leaks were noted in 2.4% of patients, and 1.2% had wound infections. Other complications were rare (Table 44-1).41

TABLE 44-1 Complications after Consecutive Microvascular Decompressions for Hemifacial Spasm (782 Operations)

| Complication | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Permanent facial weakness | 3.3 |

| Transient facial weakness | 3.2 |

| Complete ipsilateral hearing loss | 2.7 |

| CSF leak | 2.4 |

| Wound infection | 1.2 |

| Pseudomeningocele | 0.5 |

| Bacterial meningitis | 0.5 |

| Cerebellar hematoma | 0.5 |

| Infarct | 0.3 |

| Operative death | 0.1 |

| Other | <1 |

CSF, cerebrospinal fluid.

From Auger RG, Whisnant JP: Hemifacial spasm in Rochester and Olmstead County, Minnesota, 1960 to 1984. Arch Neurol 47:1233-1234, 1990.

DISABLING POSITIONAL VERTIGO AND TINNITUS

Patient Selection

Patients with disabling positional vertigo have a characteristic pattern of symptoms, the most common of which is persistent vertigo augmented by activity, but eased by bed rest. This is distinct from patients with Meniere’s disease, characterized by aural fullness, violent attacks of vertigo, tinnitus, and hearing loss lasting for several hours with the patients asymptomatic between attacks.56 In contrast to patients with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, patients with disabling positional vertigo often complain of associated nausea and occasional vomiting, or they may say that they walk as if they “had a few drinks too many.” Patients often stagger, are unable to make quick turns, and tend to fall to the affected side. Over time, 20% of affected patients develop associated cochlear compression resulting in a slowly progressive loss of hearing in the midfrequency to high-frequency range. Occasionally, patients may develop symptoms from adjacent cranial nerves, such as hemifacial spasm, ear pain (geniculate neuralgia), or trigeminal neuralgia (V2 distribution).

As previously mentioned, patients with CN VIII compression may present with isolated auditory symptoms. Typically, these patients have hearing loss in the high-frequency range that does not fluctuate.56 Differences in pure tone hearing threshold and tinnitus are also common signs of cochlear nerve compression (see Fig. 44-4).

Operative Technique for Microvascular Decompression in Disabling Positional Vertigo and Tinnitus

The position of the patient is similar to the position for hemifacial spasm, with the head rotated away 10 degrees and the vertex lowered 15 degrees toward the floor.31 The bony opening is shaped like an isosceles triangle, with the apex pointed at the junction of the sigmoid and transverse sinuses.31 The dural opening is similar to that of a hemifacial spasm approach. The intradural approach is different, however, in that the retractor blade and cottonoid are placed supralaterally over the cerebellum, elevating it off CN VIII. The root entry zone must be dissected free from the flocculus of the cerebellum more medially than in hemifacial spasm. This dissection allows for greater exposure of the veins along the brainstem, which may be the offending vessels.57–59

Patients with vertigo or dysequilibrium or both are likely to have compression of the superior vestibular nerve at or just distal to the root entry zone. Associated nausea is typically associated with compression of the inferior vestibular nerve at the brainstem. In patients with tinnitus, the surgeon must inspect the cochlear nerve from the root entry zone to the internal auditory meatus. Patients with tinnitus and associated deep ear pain with or without vertigo often have compression of the nervus intermedius and the cochlear nerve. Typically, the offending vessel is running between CN VII and VIII. Intrafascicular compression by arteries is often a difficult problem to treat, and may require division of the nervus intermedius.59

Results of Microvascular Decompression for Disabling Positional Vertigo and Tinnitus

The group with CN VIII dysfunction comprised 281 patients with disabling positional vertigo, tinnitus, hearing loss, or dysequilibrium. Patients with predominantly vestibular symptoms were noted to have proximal compression at the root entry zone. Cochlear dysfunction was associated with more peripheral compression. Of the patients with vestibular pathology, 79% were markedly improved or symptom-free after surgery, whereas only 40% of the patients with pure cochlear disturbance were significantly better.56 Improvement in tinnitus is delayed and may take 2 years. The results in disabling tinnitus are time-related. At 2 years, 90% do well; this decreases to 80% after 4 years, and then precipitously declines to 10%.

Complications of Microvascular Disabling Positional Vertigo and Tinnitus

Hearing was decreased postoperatively in 11 (4.7%) of 235 patients operated on for disabling positional vertigo or tinnitus or both. In two patients, the tinnitus continued on a worsening course. Additionally, there was one patient with transient vocal cord paresis, one patient with trochlear nerve paresis, and two patients with transient mild facial paresis.56

GLOSSOPHARYNGEAL NEURALGIA

Patient Selection

Glossopharyngeal neuralgia is characterized by sharp, lancinating, intermittent pain involving the posterior tongue, pharynx, and deep ear structures. When other etiologies are eliminated, these patients are excellent candidates for MVD.60 Glossopharyngeal neuralgia is due to vascular compression of CN IX and X. In patients with associated brainstem compression, associated symptoms may include sleep apnea, syncope, ataxia, autonomic dysreflexia, and hypertension (discussed subsequently). Some patients find relief with carbamazepine, phenytoin, or baclofen. The efficacy of pharmacotherapy has not been well defined.

Results of Microvascular Decompression in Glossopharyngeal Neuralgia

The prognosis for patients with glossopharyngeal neuralgia is quite good after MVD. Of the patients operated on by the senior author, 79% had at least 95% relief, and another 10% had at least 50% relief, with the remaining 10% considered failures.60 Based on intraoperative observations, the posterior inferior cerebellar artery was the most common cause of neural compression (39%).60

Complications of Microvascular Disease in Glossopharyngeal Neuralgia

There was one postoperative death after MVD and one death after nerve section by another surgeon, both from sequelae of intraoperative hypertension. Three patients had permanent CN IX and X palsy (8%), and four others had transient palsies (10%).60

NEUROGENIC HYPERTENSION

Patient Selection

Elevated arterial pressure not caused by well-described pathologic findings such as renal artery stenosis, pheochromocytoma, or renal disease has been termed essential hypertension.1 In 1979, Jannetta and Gendell61 first introduced the concept of neurogenic hypertension. They reported on 16 consecutive hypertensive patients with vascular compression of the left rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM). During the past 3 decades, there has been an abundance of scientific evidence in the forms of animal experiments,62–6573 postmortem anatomic dissection,66,67 operative observations,1,2,61 and radiographic findings68–70 showing that pulsatile compression of the left RVLM elicits sympathetically mediated hypertension.

Hypertensive candidates for MVD are refractory to oral antihypertensive medication, have pressure lability interfering with activities of daily living, have associated autonomic dysreflexia, or have intractable side effects from the medication. All patients must be screened for carcinoid, renal artery stenosis, pheochromocytoma, and renal diseases. Additionally, a minimum of three blood pressure measurements confirming hypertension must be documented while adhering to pharmacologic management. Although many patients had demonstration of brainstem compression by ectatic vessels on preoperative MRI, current MRI techniques have been shown to be insufficiently sensitive as a screening tool for neurogenic hypertension.71 Postoperatively, continuous blood pressure measurements are obtained for 24 hours, followed by blood pressure recordings every 6 to 8 hours for 48 hours. Daily measurements are required for 2 weeks.

Operative Technique for Neurogenic Hypertension

The operation for neurogenic hypertension is similar to the operation for glossopharyngeal neuralgia with respect to positioning, craniectomy, durotomy, and approach. The surgeon should expect to find the vertebral artery, the posterior inferior cerebellar artery, or the basilar artery causing RVLM compression.1,62,69 Mobilization of the larger vessels, especially if dolichoectatic or calcified, may be quite difficult. Multiple pieces of shredded Teflon felt are usually required to mobilize the vessel away from the point of maximal compression. Great care must be taken to avoid injury to all perforators in this region because inadvertent tearing of small arteries may cause irreversible neurologic deficits.

Results

After observing an association between hypertension and left RVLM compression, Jannetta and coworkers72 reported such compression in 51 of 53 hypertensive patients undergoing MVD for either trigeminal neuralgia or hemifacial spasm. Several years later, two articles were published within a few months of each other from different groups describing outcomes of patients with medically intractable hypertension treated with MVD of the RVLM.1,2 The results were similar. Levy and associates1 showed improvement in 72% of the patients treated, with 54% achieving normotensive pressures. Additionally, 54% of the patients with severe medically intractable hypertension were regulating their pressure with fewer medications. Similarly, Geiger and colleagues2 showed that 50% of the patients in their study were normotensive after a 1-year follow-up. The posterior inferior cerebellar artery was compressing the brainstem in 92% of the patients (Fig. 44-9).1 These studies by Geiger and Levy and their colleagues show the potential for operative intervention before irreversible end organ damage typical of poorly controlled hypertensive patients. Current randomized, multicenter, prospective trials are investigating the efficacy of MVD for neurogenic hypertension.

1. Levy E.I., Clyde B., McLaughlin M.R., Jannetta P.J. Microvascular decompression of the left lateral medulla oblongata for severe refractory neurogenic hypertension. Neurosurgery. 1998;43:1-6.

2. Geiger H., Naraghi R., Schobel H.P., et al. Decrease of blood pressure by ventrolateral medullary decompression in essential hypertension. Lancet. 1998;352:446-449.

3. Jannetta P.J., Rand R.W. Transtentorial retrogasserian rhizotomy in trigeminal neuralgia by microneurosurgical technique. Bull Los Angeles Neurol Soc. 1966;31:93-99.

4. Møller M.B., Møller A.R. Audiometric abnormalities in hemifacial spasm. Audiology. 1985;24:396-405.

5. Møller A.R., Jannetta P.J. Comparison between intracranially recorded potentials from the human auditory nerve and scalp recorded auditory brainstem responses (ABR). Scand Audiol. 1982;11:33-40.

6. Møller A.R., Jannetta P.J. Compound action potentials recorded intracranially from the auditory nerve in man. Exp Neurol. 1981;74:862-874.

7. Møller A.R., Jannetta P.J., Sekhar L.N. Contributions from the auditory nerve to the brainstem auditory evoked potentials (BAEPs): Results of intracranial recording in man. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1988;71:198-211.

8. Møller A.R., Jannetta P.J. Auditory evoked potentials recorded from the cochlear nucleus and its vicinity in man. J Neurosurg. 1983;59:1013-1018.

9. Sweet W.H., Poletti C.E. Problems with retrogasserian glycerol in the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia. Appl Neurophysiol. 1985;48:252-257.

10. Mullan S., Lichtor T. Percutaneous microcompression of the trigeminal ganglion for trigeminal neuralgia. J Neurosurg. 1983;59:1007-1012.

11. Møller M.B., Møller A.R. Brainstem auditory evoked potentials in patients with cerebellopontine angle tumors. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1983;92:645-650.

12. Laha R.K., Jannetta P.J. Glossopharyngeal neuralgia. J Neurosurg. 1977;47:316-320.

13. Broggi G., Franzini A., Lasio G., et al. Long-term results of percutaneous retrogasserian thermorhizotomy for “essential” trigeminal neuralgia: Considerations in 1000 consecutive patients. Neurosurgery. 1990;26:783-786.

14. Taha J.M., Tew J.M.J., Buncher C.R. A prospective 15-year follow-up of 154 consecutive patients with trigeminal neuralgia treated by percutaneous stereotactic radiofrequency thermal rhizotomy. J Neurosurg. 1995;83:989-993.

15. Taha J.M., Tew J.M.J. Treatment of trigeminal neuralgia by percutaneous radiofrequency rhizotomy. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 1997;8:31-39.

16. Hakanson S. Trigeminal neuralgia treated by the injection of glycerol into the trigeminal cistern. Neurosurgery. 1981;9:638-648.

17. Zakrzewska J.M. Surgery at the level of the gasserian ganglion. In: Zakrzewska J.M., editor. Trigeminal Neuralgia. London: Saunders; 1995:125-156.

18. Lunsford L.D., Bennett M.H. Percutaneous retrogasserian glycerol rhizotomy for tic douloureux, I: Technique and results in 112 patients. Neurosurgery. 1984;14:424-430.

19. Lunsford L.D., Apfelbaum R.I. Choice of surgical therapeutic modalities for treatment of trigeminal neuralgia: Microvascular decompression, percutaneous retrogasserian thermal, or glycerol rhizotomy. Clin Neurosurg. 1985;32:319-333.

20. Burchiel K.J. Percutaneous retrogasserian glycerol rhizolysis in the management of trigeminal neuralgia. J Neurosurg. 1988;69:361-366.

21. Slettebo H., Hirschberg H., Lindegaard K.F. Long-term results after percutaneous retrogasserian glycerol rhizotomy in patients with trigeminal neuralgia. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1993;122:231-235.

22. Lichtor T., Mullan J.F. A 10-year follow-up review of percutaneous microcompression of the trigeminal ganglion. J Neurosurg. 1990;72:49-54.

23. Brown J.A., Gouda J.J. Percutaneous balloon compression of the trigeminal nerve. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 1997;8:53-62.

24. Maesawa S., Salame C., Flickinger J.C., et al. Clinical outcomes after stereotactic radiosurgery for idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia. J Neurosurg. 2001;94:14-20.

25. Regis J., Metellus P., Hayashi M., et al. Prospective controlled trial of gamma knife surgery for essential trigeminal neuralgia. J Neurosurg. 2006;104:913-924.

26. Sheehan J., Pan H.C., Stroila M., Steiner L. Gamma knife surgery for trigeminal neuralgia: Outcomes and prognostic factors. J Neurosurg. 2005;102:434-441.

27. Hasegawa T., Kondziolka D., Spiro R., et al. Repeat radiosurgery for refractory trigeminal neuralgia. Neurosurgery. 2002;50:494-500.

28. Vital statistics of the United States, 1987, Vol II, part A—mortality. Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1990.

29. Casey K. Role of patient history and physical examination in the diagnosis of trigeminal neuralgia. Neurosurg Focus. 2005;18:E1.

30. Taylor J.C., Brauer S., Espir M.L. Long-term treatment of trigeminal neuralgia with carbamazepine. Postgrad Med J. 1981;28:16-18.

31. McLaughlin M.R., Jannetta P.J., Clyde B.L., et al. Microvascular decompression of cranial nerves. J Neurosurg. 1999;90:1-8.

32. Jannetta P.J., McLaughlin M.R., Casey K.F. Technique of microvascular decompression. Neurosurg Focus. 2005;18:E5.

33. Ashkan K., Marsh H. Microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia in the elderly: A review of the safety and efficacy. Neurosurgery. 2004;55:840-848.

34. Javadpour M., Eldridge P.R., Varma T.R., et al. Microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia in patients over 70 years of age. Neurology. 2003;60:520.

35. Ogungbo B.I., Kelly P., Kane P.J., Nath F.P. Microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia: Report of outcome in patients over 65 years of age. Br J Neurosurg. 2000;14:23-27.

36. Ryu H., Yamamoto S., Sugiyama K., Nozue M. Neurovascular compression syndrome of the eighth cranial nerve: What are the most reliable diagnostic signs? Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1998;140:1279-1286.

37. Sekula R.F.Jr., Marchan E.M., Fletcher L.H., et al. Microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia in the elderly. J Neurosurg Apr. 2008;108(4):688-691.

38. Barker F.G., Jannetta P.J., Babu R.P., et al. Long-term outcome after operation for trigeminal neuralgia in patients with posterior fossa tumors. J Neurosurg. 1996;84:818-825.

39. Barker F.G., Jannetta P.J., Bissonette D.J., et al. The long-term outcome of microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1077-1083.

40. Resnick D.K., Levy E.I., Jannetta P.J. Microvascular decompression for pediatric onset trigeminal neuralgia. Neurosurgery. 1998;43:804-807.

41. Auger R.G., Whisnant J.P. Hemifacial spasm in Rochester and Olmstead County, Minnesota, 1960 to 1984. Arch Neurol. 1990;47:1233-1234.

42. Levy E.I., Resnick D.K., Jannetta P.J., et al. Pediatric hemifacial spasm: The efficacy of microvascular decompression. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1997;27:238-241.

43. Alexander G.E., Moses H.III. Carbamazepine for hemifacial spasm. Neurology. 1982;32:286-287.

44. Sandyk R., Gillman M.A. Clonazepine in hemifacial spasm. Int J Neurosci. 1987;33:261-264.

45. Dutton J.J., Buckley E.G. Long-term results and complications of botulinum A toxin in the treatment of blepharospasm. Ophthalmology. 1988;95:1529-1534.

46. Taylor J.D.N., Kraft S.P., Kazdan M.S., et al. Treatment of blepharospasm and hemifacial spasm with botulinum A toxin: A Canadian multicentre study. Can J Ophthalmol. 1991;26:133-138.

47. Yoshimura D.M., Aminoff M.J., Tami T.A., et al. Treatment of hemifacial spasm with botulinum toxin. Muscle Nerve. 1992;15:1045-1049.

48. Park Y.C., Lim J.K., Lee D.K., et al. Botulinum A toxin treatment of hemifacial spasm and blepharospasm. J Korean Med Sci. 1993;8:334-340.

49. Møller A.R., Jannetta P.J. Microvascular decompression in hemifacial spasm: Intraoperative electrophysiological observations. Neurosurgery. 1985;16:612-618.

50. Montero J., Junyent J., Calopa M., et al. Electrophysiological study of ephaptic axono-axonal responses in hemifacial spasm. Muscle Nerve. 2007;35:184-188.

51. Kong D.S., Park K., Shin B.G., et al. Prognostic value of the lateral spread response for intraoperative electromyography monitoring of the facial musculature during microvascular decompression for hemifacial spasm. J Neurosurg. 2007;106:384-387.

52. Barker F.G., Jannetta P.J., Bissonette D.J., et al. Microvascular decompression for hemifacial spasm. J Neurosurg. 1995;82:201-210.

53. Iwakuma T., Matsumoto A., Nakamura N. Hemifacial spasm: Comparison of three different operative procedures in 110 patients. J Neurosurg. 1982;57:753-756.

54. Auger R.G., Piepgras D.G., Laws E.R.Jr. Hemifacial spasm: Results of microvascular decompression of the facial nerve in 54 patients. Mayo Clin Proc. 1986;61:640-644.

55. Loeser J.D., Chen J. Hemifacial spasm: Treatment by microsurgical facial nerve decompression. Neurosurgery. 1983;13:141-146.

56. Møller M.B., Møller A.R., Jannetta P.J., et al. Microvascular decompression of the eighth nerve in patients with disabling positional vertigo: Selection criteria and operative results in 207 patients. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1993;125:75-82.

57. Jannetta P.J. Trigeminal neuralgia [Letter]. Neurosurgery. 1986;18:677.

58. Jannetta P.J. Neurovascular cross-compression in patients with hyperactive dysfunction symptoms of the eighth cranial nerve. Surg Forum. 1975;26:467-469.

59. Jannetta P.J. Neurovascular cross compression of the eighth nerve in patients with vertigo and tinnitus. In: Samii M., Jannetta P.J., editors. The Cranial Nerves. Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, 1981.

60. Resnick D.K., Jannetta P.J., Bissonnette D., et al. Microvascular decompression for glossopharyngeal neuralgia. Neurosurgery. 1995;36:64-68.

61. Jannetta P.J., Gendell H.M. Clinical observations on etiology of essential hypertension. Surg Forum. 1979;30:431-432.

62. Granata A.R., Ernsberger P., Reis D.J. Hypotension and bradycardia elicited by histamine into the C1 area of the rostral ventrolateral medulla. Eur J Pharmacol. 1987;136:157-162.

63. Morrison S.H., Milner T.A., Reis D.J. Reticulospinal vasomotor neurons of the rat rostral ventrolateral medulla: Relationship of sympathetic nerve activity and the C1 adrenergic cell group. J Neurosci. 1988;8:1286-1301.

64. Segal R., Gendell H.M., Canfield D., et al. Cardiovascular response to pulsatile pressure applied to ventrolateral medulla. Surg Forum. 1979;30:433-435.

65. Segal R., Jannetta P.J., Wolfson S.K.J., et al. Implanted pulsatile balloon device for simulation of neurovascular compression syndromes in animals. J Neurosurg. 1982;57:646-650.

66. Naraghi R., Gaab M.R., Walter G.F. Neurovascular compression as a cause of essential hypertension: A microanatomical study. Adv Neurosurg. 1989;17:182-186.

67. Naraghi R., Gaab M.R., Walter G.F., Kleineberg B. Arterial hypertension and neurovascular compression at the ventrolateral medulla: A comparative microanatomical and pathological study. J Neurosurg. 1992;77:103-112.

68. Kleineberg B., Becker H., Gaab M.R. Neurovascular compression and essential hypertension: An angiographic study. Neuroradiology. 1991;33:2-8.

69. Kleineberg B., Becker H., Gaab M.R., Naraghi R. Essential hypertension associated with neurovascular compression. Neurosurgery. 1992;30:834-841.

70. Naraghi R., Geiger H., Crnac J., et al. Posterior fossa neurovascular anomalies in essential hypertension. Lancet. 1994;344:1466-1470.

71. Colon G.P., Quint D.J., Dickenson L.D., et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of ventrolateral medullary compression in essential hypertension. J Neurosurg. 1998;88:226-231.

72. Jannetta P.J., Segal R., Wolfson S.K.J. Neurogenic hypertension: Etiology and surgical treatment, I: Observations in 53 patients. Ann Surg. 1985;201:391-398.

73. Jannetta P.J., Segal R., Wolfson S.K., et al. Neurogenic hypertension: Etiology and surgical treatment, II: Observations in an experimental nonhuman primate model. Ann Surg. 1985;202:253-261.