Opening Round

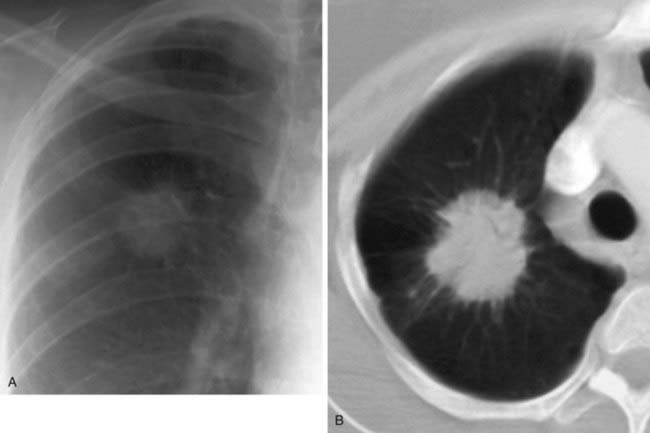

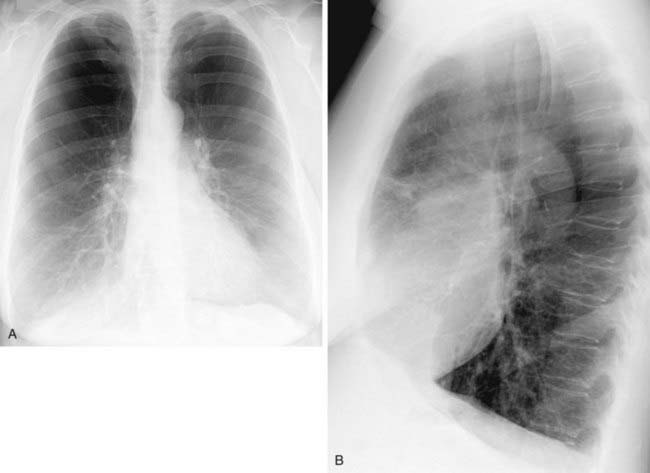

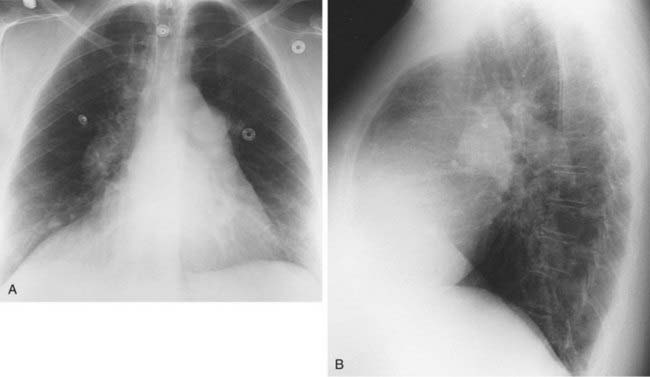

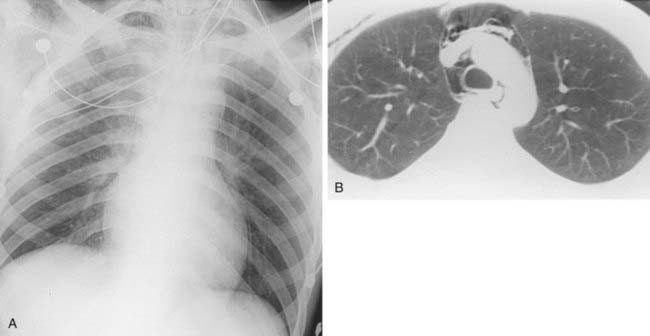

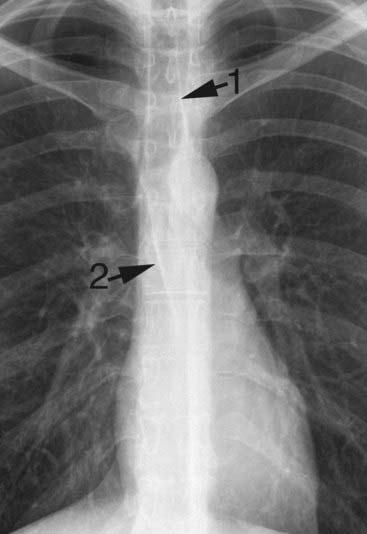

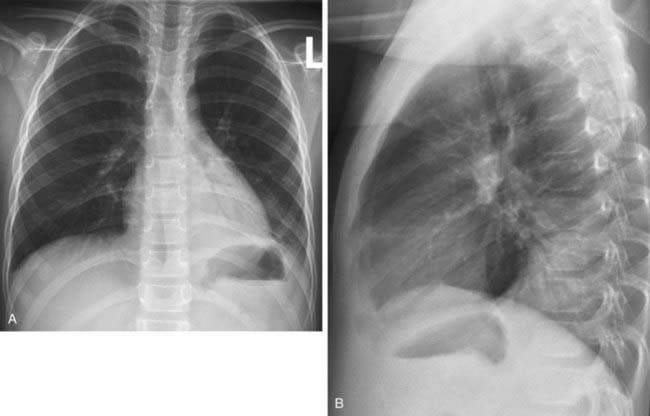

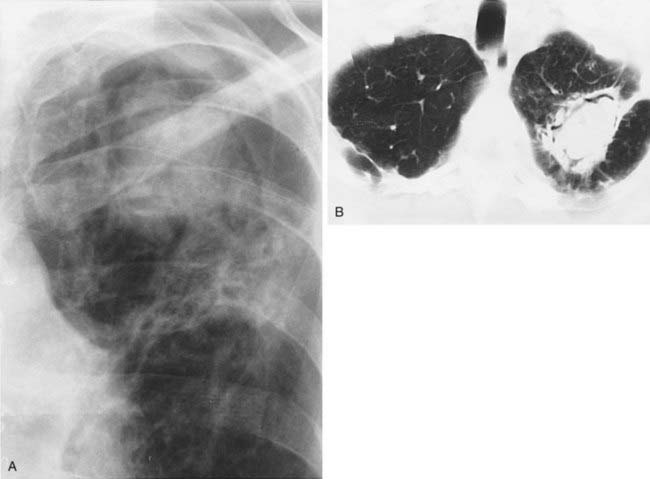

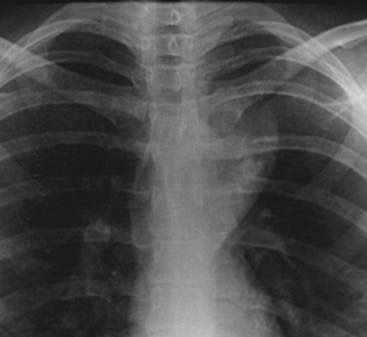

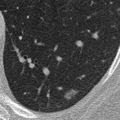

Spontaneous Pneumothorax Secondary to Ruptured Bleb

2 Spontaneous, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic infiltrative lung disease (e.g., Langerhans cell histiocytosis and lymphangioleiomyomatosis), malignant neoplasms (e.g., metastatic sarcoma), trauma, catamenial pneumothorax, iatrogenic, barotrauma, and infection (e.g., lung abscess and septic infarcts).

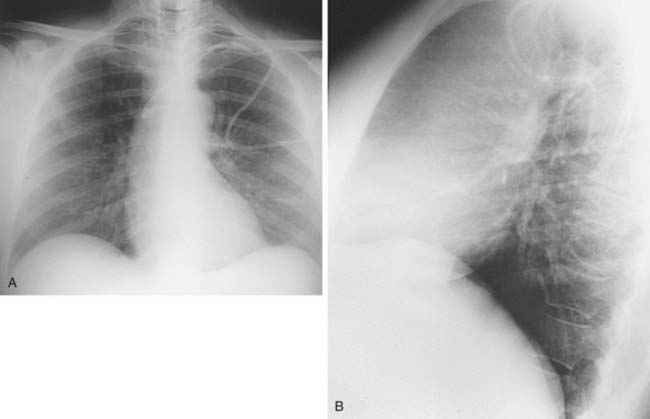

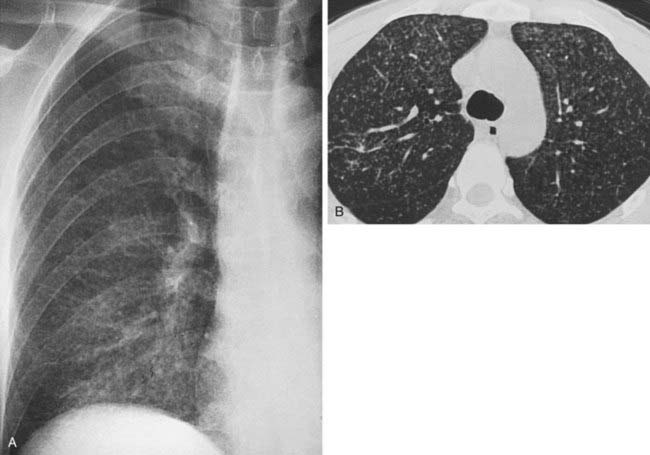

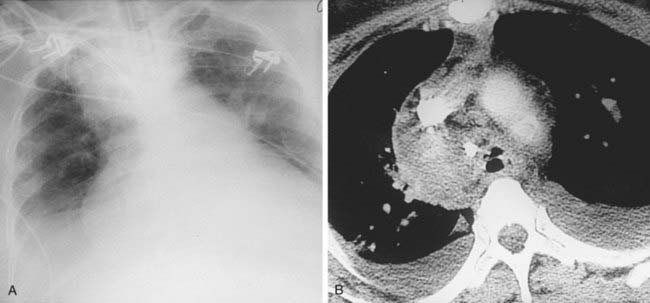

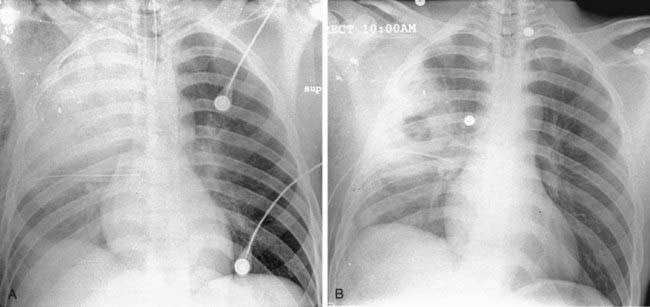

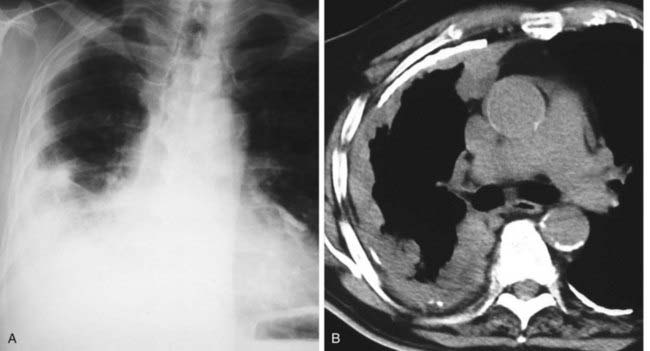

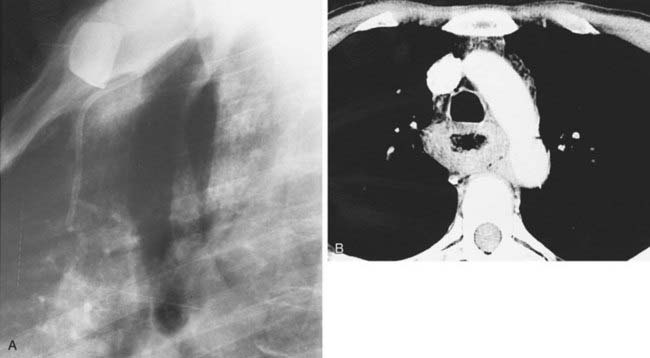

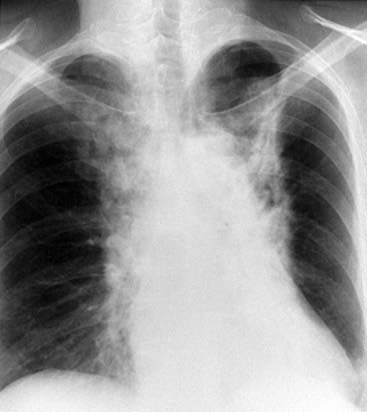

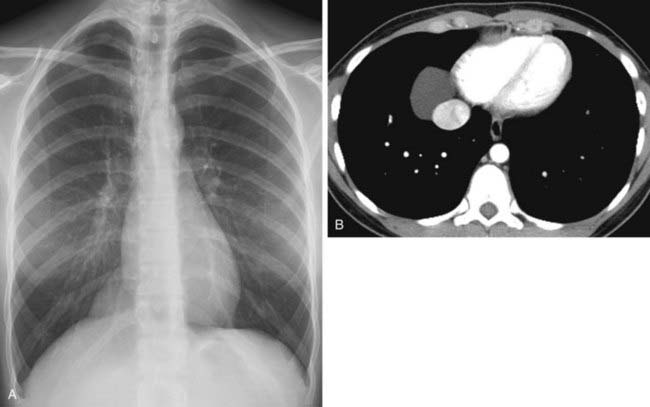

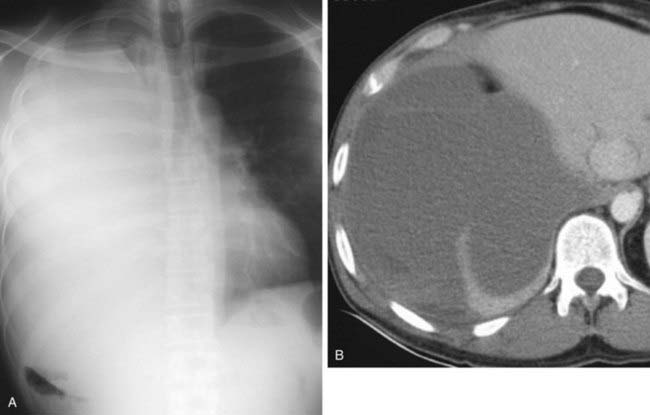

Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Complicated by Left Anteromedial Pneumothorax From Barotrauma

1 ARDS is a clinical diagnosis of acute respiratory failure characterized by profound hypoxia accompanied by diffuse parenchymal opacification on chest radiography.

2 Sepsis, trauma, severe pneumonia, circulatory shock, aspiration, inhaled toxins, drug overdose, near drowning, and multiple blood transfusions.

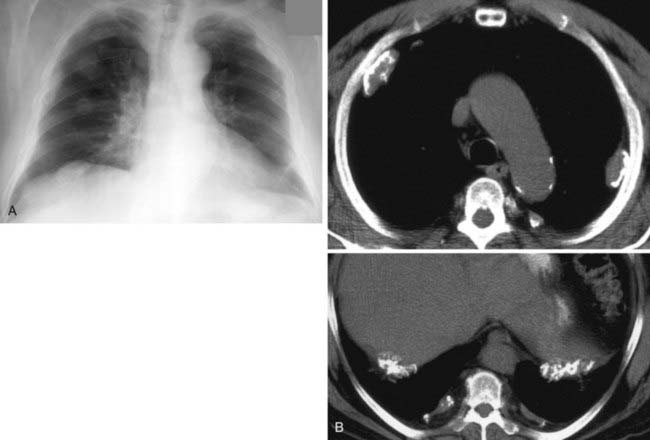

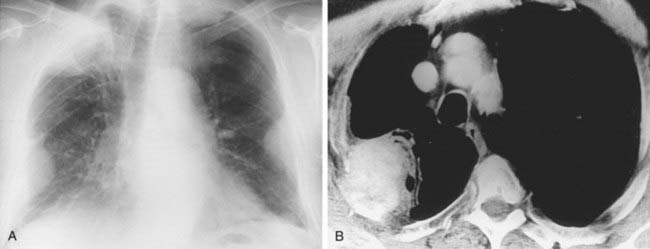

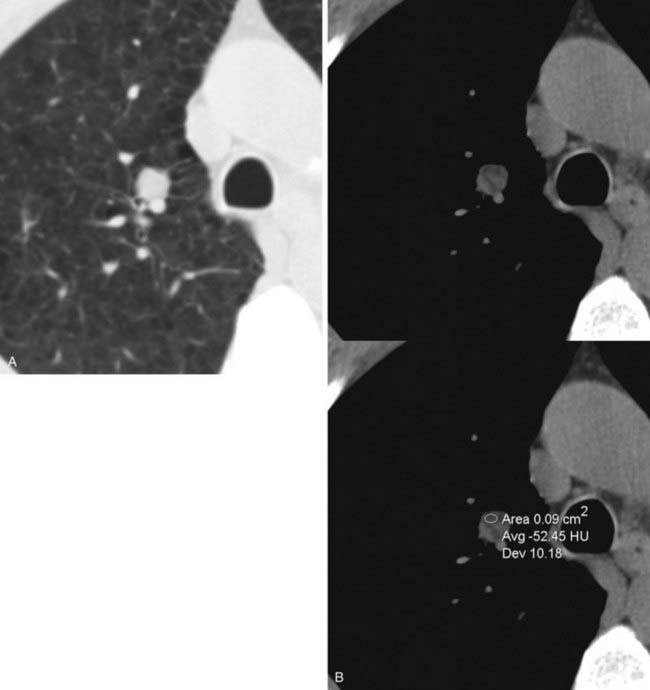

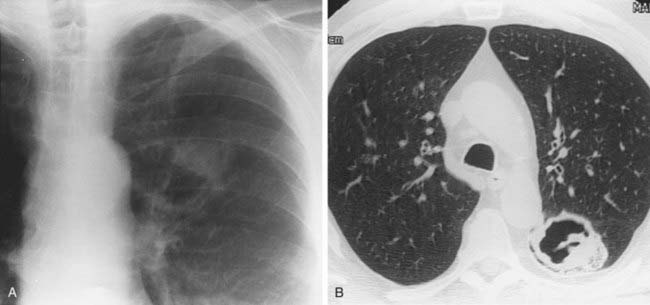

4 Bronchial artery embolization and surgical resection are the most common therapeutic options. Other reported treatments include direct instillation of amphotericin B via a percutaneous catheter into the cavity and systemic antifungal therapy (usually as adjunctive therapy in combination with surgery).

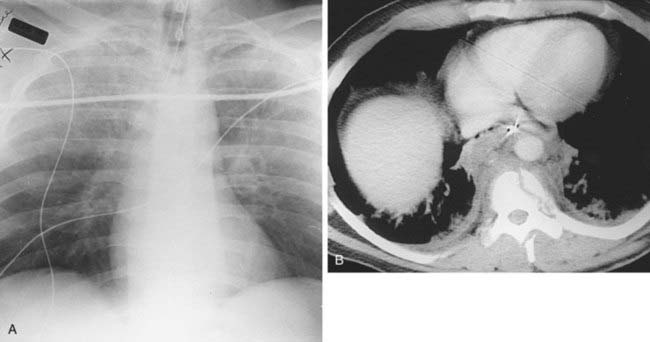

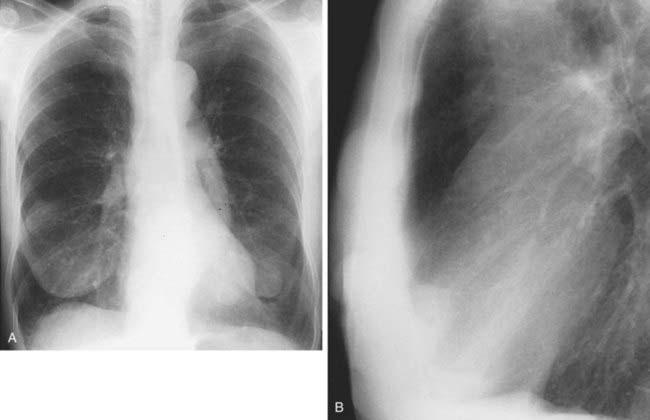

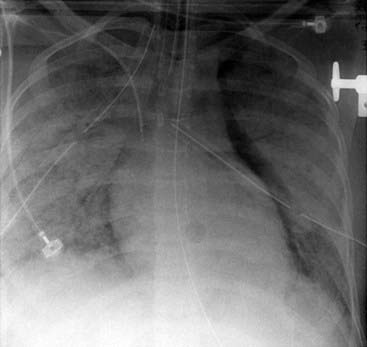

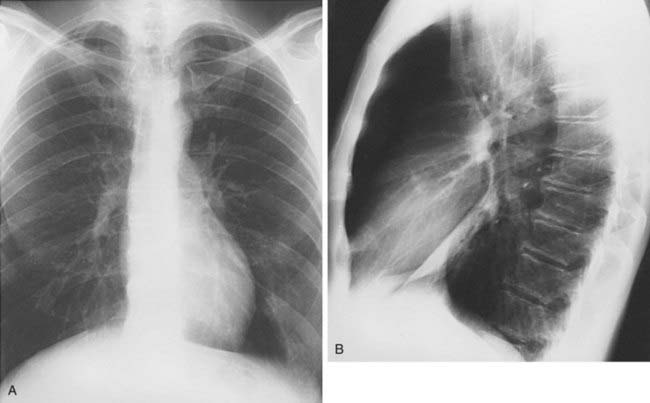

1 Endobronchial tumor, mucus plug, malpositioned endotracheal tube, foreign body, post-traumatic injury, tuberculous stenosis.

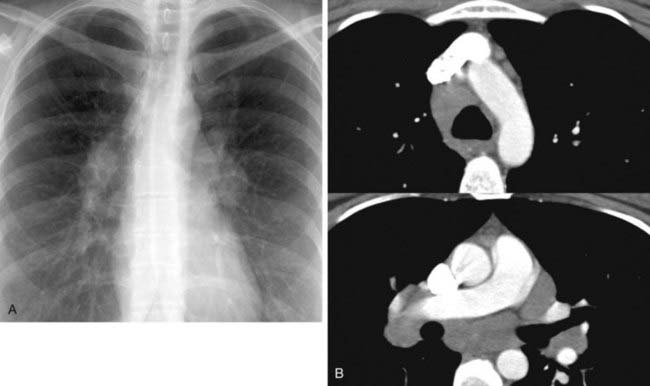

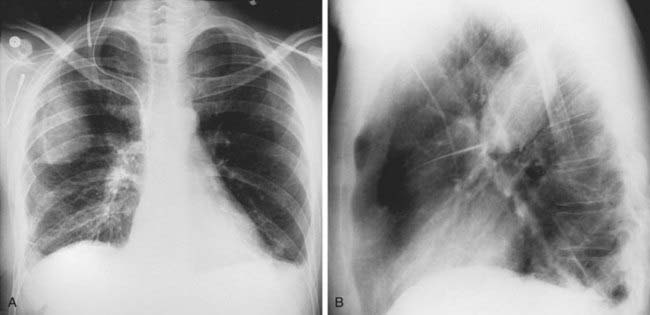

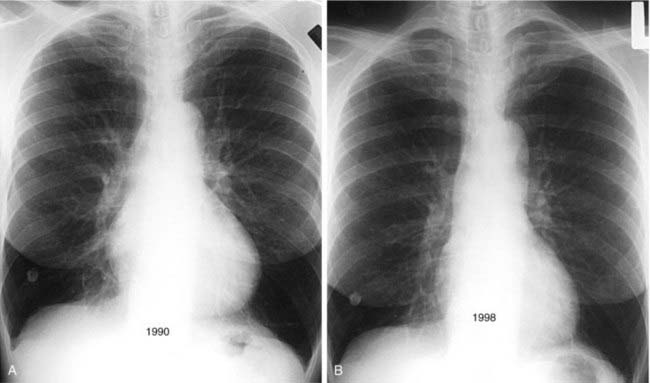

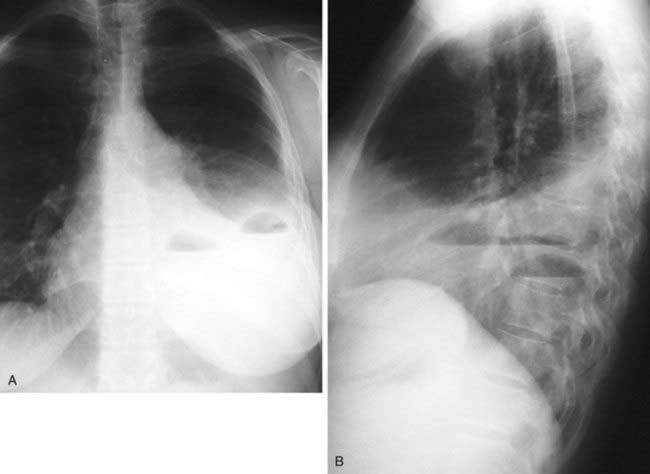

3 Complete or near-complete opacification of a hemithorax, shift of the mediastinum to the affected side, elevation of the ipsilateral hemidiaphragm (not apparent in acute hemothorax), compensatory overinflation of the contralateral lung, enlargement of retrosternal clear space on lateral radiograph.

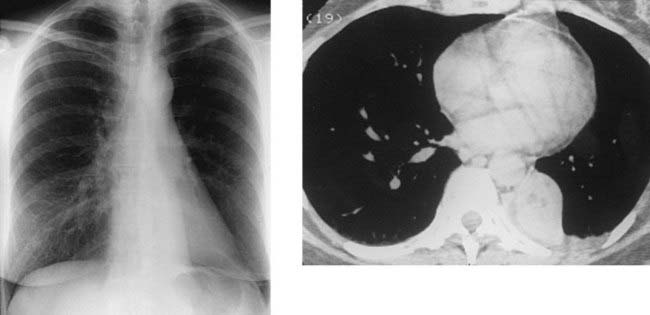

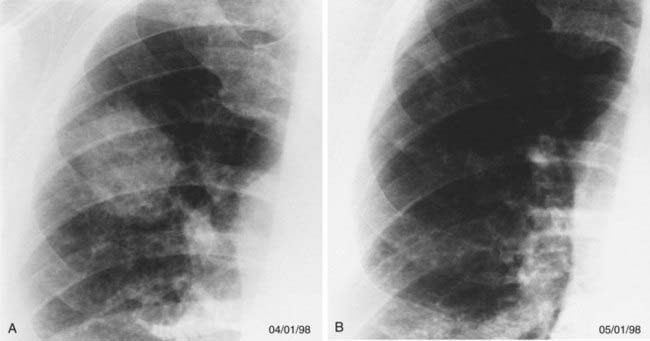

4 Trauma (blunt or penetrating), iatrogenic (central venous catheter insertion), complication of surgery, anticoagulation therapy, malignant tumor, catamenial hemothorax.