Chapter 99 Open versus Arthroscopic Repair for Shoulder Instability: What’s Best?

Shoulder dislocations are a common sports injury, especially in contact sports such as hockey,1,2 rugby,3,4 and all forms of football,5,6 but also in sports associated with falls, such as skiing,7,8 and in sports in which shoulder movements are integral to the game, such as tennis, badminton, swimming, and baseball.3,9, 10 Most of these dislocations involve anterior dislocation,3,7,8,11–15 during which the glenohumeral joint actually is disrupted. In some, the dislocation reduces itself spontaneously.16 Other patients require manual reduction, often requiring anesthesia. Immediate conservative management after reduction may consist of a sling, more to alleviate pain and worry than to protect the joint, and avoidance of sporting activities for an extended time, possibly associated with analgesics, physiotherapy, or both; but the research on the acute management of shoulder dislocations is quite inconclusive,17 and there is extreme variability in clinical practice.18–20

Irrespective of how shoulder dislocations are managed immediately after injury,21 the risk for redislocating a shoulder is high without surgical repair, in some series approaching 90%, especially in younger athletes.2,21 Conservative management, including the use of a sling in the short term and physiotherapy, is of uncertain benefit21 and may actually increase this risk by delaying more definitive treatment.22 Consequently, surgery commonly is considered, especially for those who are young and those wanting to return to athletic activities.

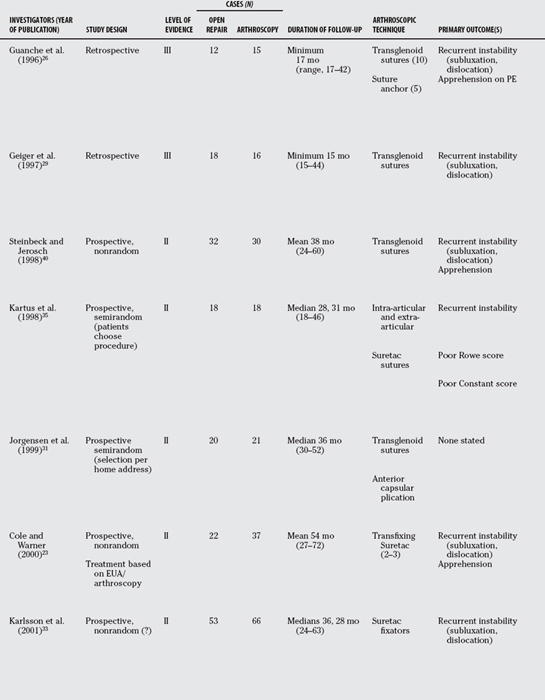

Currently, the surgical options can be classified broadly into open surgical repair and arthroscopic repair; however, ongoing debate rages regarding which is most effective for the treatment of shoulder dislocations, which has led to two meta-analyses and a further published review of the literature.23–25 Certainly, early investigators seemed to identify either no difference between the approaches or some superiority of open surgery, but this conclusion largely was based on a single outcome: joint stability. Despite these early results, the arthroscopic repair of shoulder instability seems to have gathered momentum since the late 1990s.24,25 This chapter is a review of the relatively limited comparative evidence, examining not only joint stability, but also several other outcomes of clinical interest. Note that these comparisons all are relatively recent, the first publication having been in 1996.26

SURGICAL OPTIONS

As stated earlier, the surgical options can be divided broadly into those performed via open surgery and those performed arthroscopically, but there is a variety of techniques that can be utilized within each approach. This especially appears to be true with arthroscopic shoulder repair, possibly because this approach is newer, and hence more in its evolutionary phase.24,25 Some of the initial arthroscopic approaches included staple capsulorrhaphy, transglenoid suturing, bioabsorbable tack fixation, suture anchor fixation with capsular plication, and the combined use of intra-articular and extra-articular Suretac sutures.26–41 More recently, most surgeons utilize a suture anchor system with or without knot tying. This variety, in itself, makes it difficult to compare between studies, and between the arthroscopic and open surgery approaches.

OUTCOMES OF INTEREST

Because there has been variability in the surgical approaches used, there also has been considerable variability in the outcomes measured. Virtually all investigators who have assessed open or arthroscopic repair alone or relative to each other have utilized recurrent instability as an outcome, and often as the primary outcome. However, how recurrent instability is defined has differed, some including a positive apprehension sign as an indicator of instability. No other single outcome has spanned all studies, but several investigators have adopted the use of validated multidimensional instruments, especially the shoulder-specific (joint-specific) evaluation instruments called the Rowe Rating Scale,26,29,31,33,35–38,40 which initially was called the Rating Sheet for Bankart Repair, and the Constant Score.28,31, 33, 35, 37, 38 Other shoulder-specific summation scores that have been utilized are the modified Rowe Rating Scale,28 the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) Standardized Shoulder Assessment Form,39,41 and the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) Shoulder Rating Scale.26,36 Kirkley and colleagues’43 Western Ontario Shoulder Instability (WOSI) scale, another instrument used in one of the comparative studies,42 offers the advantage of being a disease-specific, rather than just a joint-specific, instrument, in that it specifically evaluates shoulder function in patients with shoulder instability. Like the Rowe and Constant scales, each of these instruments generates a summation score, often expressed as a percentage, which is derived from evaluations of individual parameters, such as pain, function, range of motion (ROM), strength, and stability, though which parameters are included, and how they are weighted varies from scale to scale. Some investigators also have compared the open and arthroscopic approaches with respect to the change in summation score from pre-operative baseline to final evaluation.

Another summation score that has been used is the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36),27 an instrument with several subscales to evaluate self-perceived patient well-being. The SF-36 is not specific to any joint or to any 1 medical or surgical condition; as such, it allows for comparison between conditions, which can be useful if one wishes to determine the relative worth of treatment of 1 condition versus another.

REVIEW OF OUTCOMES

Instability

As shown in Table 99-1, the earliest studies comparing arthroscopic repair of shoulder instability with the long-established open approach demonstrated superiority of the latter26,29, 40 (Level III). For example, among 12 patients undergoing open repair and 15 arthroscopy, Geiger and coworkers29 identified a 44% rate of instability among those who had undergone arthroscopy but no instances of instability in those who had had open surgery (P < 0.05). Similarly, in the studies by Guanche and researchers26 (Level III) and Steinbeck and Jerosch40 (Level II), the rates of instability were 33% and 17% in those who had had arthroscopy versus 8% and 6% in the open surgery group, respectively. Though clinically appreciable, these latter 2 differences did not achieve statistical significance. Nonetheless, these 3 studies were among the 6 included in the meta-analysis published by Freedman and colleagues24 in 2004 and the 11 studies included in the meta-analysis performed by Mohtadi and coworkers25 in 2005, both of which conclude that open is superior to arthroscopic repair, in terms of instability rates (Level III).

Later studies have been much less consistent. A few studies have uncovered some advantage of open surgery, such as Rhee and colleagues37 (25% arthroscopy vs. 13% open; P < 0.05), Hubbell and coworkers30 (60% vs. 0%; P < 0.05), Cole and coauthors27 (24% vs. 16%; P value not significant [NS]), Karlsson and researchers33 (15% vs. 10%; P value NS), and Sperber and investigators38 (23% vs. 13%; P value NS) (Level III). In contrast, several other studies revealed no difference at all between the 2 surgical approaches,28,31, 35, 36, 39, 42 and 1 study actually demonstrated a clinically impressive, albeit not statistically significant, difference in favor of arthroscopy (6% arthroscopy vs. 24% open; P value NS) (Level III). In some instances, no cases of postrepair instability were identified in either group.28,35, 39

As stated earlier, 1 problem interpreting these data is that instability has not been consistently defined. For example, Kartus and colleagues35 limited the designation of instability to shoulder dislocation, which clearly might have reduced the numbers this group considered unstable versus other investigative teams that included a positive apprehension sign. Nonetheless, what is apparent is that it is less clear now that open repair provides a lower risk for instability than it may have been 1 decade ago, possibly because of improved arthroscopic techniques and equipment, and increased experience among surgeons. It also is apparent, and quite understandable, that the results of arthroscopy are quite operator dependent.

Apprehension

Because a positive apprehension sign generally is indicative of shoulder instability, it is reasonable to expect that the presence of apprehension would parallel that of instability. But how sensitive and specific the apprehension sign is as an indicator of joint instability is a question that must be considered, as well as its level of intrarater and inter-rater reliability. Moreover, few current studies have examined the reliability, sensitivity, and specificity of most orthopedic signs,44 and some evidence suggests that the inter-rater reliability of the apprehension sign (the rate at which different examiners agree that the same shoulder is either stable or unstable) may be as low as 50%, which is no better than the flip of a coin.45

In Geiger and coworkers’29 study, the rates for shoulder instability were 17% and 6% for postarthroscopy and open repair, respectively, and a positive apprehension sign was detected in 30% and 6%, suggesting that almost half the patients with arthroscopy with positive apprehension signs were found not to have any other evidence of instability (Level III). In this study, the former intergroup difference, for instability, failed to achieve statistical significance, but the latter difference, for a positive apprehension sign, did. Concern exists regarding that, in several other studies, the presence of a positive apprehension sign was deemed enough for the investigators to consider the joint unstable, and the presence or absence of a positive apprehension sign per se was not reported.

Summation Scores

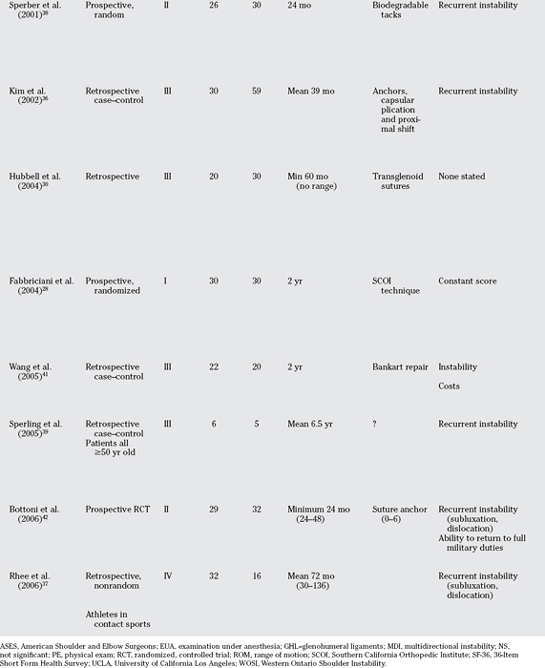

As stated earlier, the Rowe Shoulder Scale was the most commonly used summation instrument,23,26,27,29,31,33,35–38,40 followed by the Constant Score,28,31, 33, 35, 37, 38 with both scores often reported using an ordinal scale; for example, scores of 90% or greater might be categorized as an “excellent” result, scores from 75 to 89 a “good” result, scores from 51 to 74 “fair,” and scores of 50 or less “poor.” Consequently, the most commonly reported result has been the percentage of patients who achieved a good-to-excellent result, when combining the various parameters included in the instrument. With the Rowe Scale, these parameters are function, pain severity, joint stability, and ROM28; with the Constant Score, they are pain, function, ROM, and strength28 (Level I). Interestingly, the tendency toward joint instability being more common among those who had undergone arthroscopic repair has not been reflected in either the Rowe or Constant scores, despite joint stability being a parameter in the Rowe Scale. For example, with the possible exception of the study by Geiger and coworkers,29 in no study was there a statistically significant intergroup difference using either scale. In Geiger and coworkers’29 study, 83% in the open group were assigned a postoperative functional rating of good to excellent, compared with only 50% in the arthroscopy group (P = 0.05) (Level III); however, it is not clear whether these ratings were based solely on the Rowe score, some combination of the Rowe score and a joint instability rating, or some other factor(s). If one assumes that Geiger’s group did base their good-to-excellent rating solely on the Rowe score, then the overall average percentage of good-to-excellent ratings based on Rowe scores across the 10 studies that reported this parameter using this ordinal scale was 88% for open repair and 86% for arthroscopy, and the overall weighted average percentage (weighted by the number of subjects per group per study) of good-toexcellent ratings was 82% for the open group versus 77% for those who received arthroscopic repair (x2 = 1.83; P = 0.17, NS) (Table 99-2). Excluding Geiger and coworkers’29 study, the percentages are 88% versus 90% overall and 78% versus 79% weighted, respectively, which, again, is not a statistically significant difference (Level III). Constant scores actually trend toward favoring arthroscopy, with 94% in the arthroscopy group receiving good-to-excellent ratings versus 89% in the subjects with open repair; but again, this difference is not statistically significant (x2 = 1.48; P = 0.20, NS) (see Table 99-2). Moreover, caution should be exercised interpreting the coalesced data because different investigative teams defined the various ordinal categories differently. For example, in 1 study, any Rowe score from 75 to 89 was considered good,31 but in another study, only scores from 81 to 90 were so designated, with scores from 70 to 80 considered fair35; in these same two studies, a “poor” result was defined as less than 50 and less than 70, respectively.

TABLE 99-2 Rowe and Constant Scores in Patients after Arthroscopic versus Open Repair of Shoulder Instability

No summation instrument besides the Rowe or Constant scores has been utilized in a published comparison between open and arthroscopic shoulder repair more than twice; therefore, combining data across studies either cannot be done or would yield an insufficient number of subjects to be meaningful. However, with the exception of the UCLA Shoulder Rating Scale score being greater in the arthroscopy group in a single study,36 where a higher score corresponds to a better result, no statistically significant differences have been noted with any scale.

Range of Motion

As equivocal as the data are with respect to virtually every other outcome, the evidence for shoulder ROM is reasonably clear. Joint shoulder ROM or loss of ROM was reported as a separate outcome in 10 of the comparison studies,26–30,33,35,38,39,42 most often referring to external rotation with the shoulder abducted and forward flexion.

In no study was ROM in any plane superior in the open surgery group. Conversely, a statistically significant advantage of arthroscopic repair was identified by 6 investigative teams, and this was noted both with external rotation30,33, 35, 42 and forward flexion26,27, 30 (Level III). This discrepancy favoring arthroscopic repair was evident even in Guanche and researchers’26 study, in which arthroscopy was associated with greater than a 33% rate of instability and fewer than half of patients with arthroscopy were deemed to have had a “good” or “excellent” result,29 and Hubbell and coworkers’30 study, in which 60% versus 0% of the patients with arthroscopy developed recurrent instability (Level III). Despite these seemingly poor results among the patients with arthroscopy, at least in terms of stability, nonetheless, there was a mean of 5.1 degrees of forward flexion lost in those undergoing open repair versus just a 1.0-degree loss in the arthroscopy group in the former study (P = 0.02)29; and 45% of the patients with open surgery versus 0% after arthroscopy suffered a loss of external rotation in the latter study (P < 0.05).30

In 2001, Kailes and Richmond32 published an article comparing arthroscopic versus open repair of shoulder instability using expected value decision analysis (Level III). Basing their analysis on no study published after 1997, and hence emphasizing data generally favoring open versus arthroscopic repair and studies generally examining 1 approach versus the other, rather than comparative studies, these authors predicted a rate of recurrent instability among those receiving arthroscopic repair at 35% versus just 5% in the open surgery group. However, they also estimate that 40% of those undergoing open repair would lose shoulder ROM versus just 10% for arthroscopy. Their predictions for were identical for all other outcomes, including minor complication rate (2%), major complication rate (2%), time decrement for rehabilitation and minor complications (4.5 and 3.0 months, respectively), functional decrement for major complications,25 utility of stability without recurrences (1.0 out of 1), utility of recurrent instability (0.4 out of 1), and disutility of decreased ROM (0.1 out of 1).32

Other Outcomes

As stated previously, no other outcome has been reported in any more than a few studies, making comparisons between open and arthroscopic repair difficult for these parameters. In studies in which shoulder dislocations, subluxations, and/or instability were found to be more common in the arthroscopy group, a return to sports and especially to contact sports was less likely in this group as well.29,30 Conversely, when there was no intergroup difference in the rate of instability, there similarly was no difference in the rate of return to athletics or other previous activities.27,31 One study35 examined for the radiographic presence of either drill holes or cysts, the implication being that these represent damage to bone; these abnormalities were statistically more common in the open group (56% vs. 23%; P < 0.05) (Level II). The only 2 studies that evaluated costs, 1 in the United States41 and 1 in Germany,46 both discovered that arthroscopic repair of the unstable shoulder was significantly less costly, largely because of the reduced need for postoperative hospitalization after arthroscopic versus open procedures.

One outcome that is conspicuously missing from studies is subscapularis weakness, which could be different in the 2 groups, because of significant muscle disruption that occurs with the open procedure that generally is not an issue with arthroscopy. In 1 study, 12 patients with shoulder instability who underwent arthroscopic stabilization were compared with 10 who underwent open surgery and 12 healthy control subjects47 (Level III). Whereas none of the patients with arthroscopy exhibited any subscapularis weakness after surgery, such weakness was noted in 7 of the 10 patients who underwent open surgery (P < 0.05), and magnetic resonance imaging revealed evidence of subscapularis muscle atrophy in the latter group as well. Another study demonstrated that the subscapularis weakness that occurs after open capsular shift lasts an average of almost 9 weeks, but that all patients had regained full strength within 20 weeks.48 This difference may be 1 of the reasons behind the slightly higher Constant scores exhibited by patients with arthroscopy, because strength is 1 of the 4 major subscales.

SUMMARY OF LITERATURE

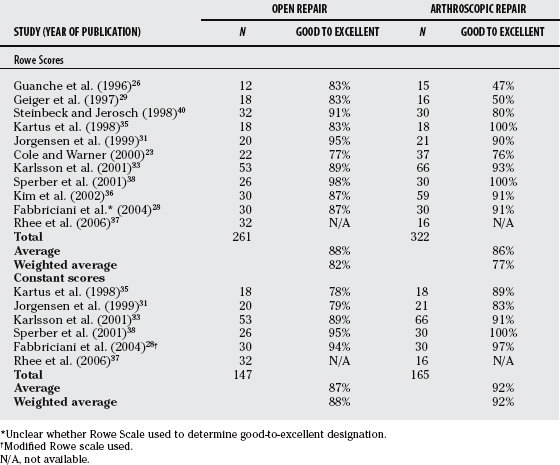

The learning curve for shoulder stabilization surgery is not short and should not be encouraged for surgeons performing infrequent shoulderstabilizing surgeries. Skills training is available through many societies and organizations, and is an essential part of obtaining and maintaining safe and effective techniques. Many of the surgical steps required to perform an arthroscopic stabilization can be practiced outside the operating room, for example, arthroscopic knot-tying techniques, suture passing, management strategies, and safe and effective portal placement. As with any procedure, patient selection is important. Ideal patients for arthroscopic stabilization would have a soft-tissue Bankart lesion because large glenoid rim fractures might compromise the ability to stabilize the joint. If the status of the glenoid is uncertain on the plain films, then a CT scan with three-dimensional reconstruction is recommended. If at the time of scope the inferior glenohumeral ligaments have avulsed off the humeral neck, the so-called HAGL (humeral avulsion glenohumeral ligaments) lesion, then this is best managed through an open approach (Level V). Athletes involved with throwing or overhead sports such as tennis and volleyball are good candidates for an arthroscopic approach because it is easier to maintain external rotation and sport function. Young athletes with an acute anterior dislocation should be informed about the option of surgical stabilization even after a single dislocation to prevent ongoing instability, as well as the subsequent soft-tissue and bone injury associated with multiple recurrences. The surgeon must avoid overconstraining the shoulder joint whether the surgery is performed open or arthroscopic because most patients would choose instability over stiffness and loss of function. Severe motion loss is strongly correlated with arthritis of the glenohumeral joint. Table 99-3 provides a summary of recommendations.

| STATEMENT | LEVEL OF EVIDENCE/GRADE OF RECOMMENDATION | REFERENCES |

|---|---|---|

1 Gerberich SG, Finke R, Madden M, et al. An epidemiological study of high school ice hockey injuries. Childs Nerv Syst. 1987;3:59-64.

2 Hovelius L. Shoulder dislocation in Swedish ice hockey players. Am J Sports Med. 1978;6:373-377.

3 Hazmy CH, Parwathi A. Sports-related shoulder dislocations: A state-hospital experience. Med J Malaysia. 2005;60(suppl C):22-25.

4 Brooks JH, Fuller CW, Kemp SP, Reddin DB. Epidemiology of injuries in English professional rugby union: Part 2 training Injuries. Br J Sports Med. 2007;39:767-775.

5 Pagnani MJ, Dome DC. Surgical treatment of traumatic anterior shoulder instability in American football players. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84-A:711-715.

6 Roberts SN, Taylor DE, Brown JN, et al. Open and arthroscopic techniques for the treatment of traumatic anterior shoulder instability in Australian rules football players. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1999;8:403-409.

7 Kocker MS, Feagin JAJr. Shoulder injuries during alpine skiing. Am J Sports Med. 1996;24:665-669.

8 Weaver JK. Skiing-related injuries to the shoulder. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987;216:24-28.

9 Perry J. Anatomy and biomechanics of the shoulder in throwing, swimming, gymnastics, and tennis. Clin Sports Med. 1983;2:247-270.

10 Bak K, Faunø P. Clinical findings in competitive swimmers with shoulder pain. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25:254-260.

11 Hazmy CH, Parwathi A. The epidemiology of shoulder dislocation in a state-hospital: A review of 106 cases. Med J Malaysia. 2005;60(suppl C):17-21.

12 Hoelen MA, Burgers AM, Rozing PM. Prognosis of primary anterior shoulder dislocation in young adults. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1990;110:51-54.

13 Hovelius L. Incidence of shoulder dislocation in Sweden. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982;166:127-131.

14 Owens BD, Duffey ML, Nelson BJ, et al. The incidence and characteristics of shoulder instability at the United States Military Academy. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:1168-1173.

15 Simonet WT, Melton LJ3rd, Cofield RH, Ilstrup DM. Incidence of anterior shoulder dislocation in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1984;186:186-191.

16 Saragaglia D, Picard F, Le Bredonchel T, et al. [Acute anterior instability of the shoulder: Short- and mid-term outcome after conservative treatment] [In French]. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 2001;87:215-220.

17 Handoll HH, Hanchard NC, Goodchild L, Feary J. Conservative management following closed reduction of traumatic anterior dislocation of the shoulder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;25:CD004962.

18 Chong M, Karataglis D, Learmonth D. Survey of the management of acute traumatic first-time anterior shoulder dislocation among trauma clinicians in the UK. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2006;88:454-458.

19 Buss DD, Lynch GP, Meyer CP, et al. Nonoperative management for in-season athletes with anterior shoulder instability. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:1430-1433.

20 te Slaa RL, Wijffels MP, Marti RK. Questionnaire reveals variations in the management of acute first time shoulder dislocations in the Netherlands. Eur J Emerg Med. 2003;10:58-61.

21 Chalidis B, Sachinis N, Dimitriou C, et al. Has the management of shoulder dislocation changed over time? Int Orthop. 2007;31:385-389.

22 Kirkley A, Werstine R, Ratjek A, Griffen S. Prospective randomized clinical trial comparing the effectiveness of immediate arthroscopic stabilization immobilization and rehabilitation in first traumatic anterior dislocations of the shoulder: Long-term evaluation. Arthroscopy. 2005;21:55-63.

23 Cole BJ, Warner JJP. Arthroscopic versus open bankart repair for traumatic anterior shoulder instability. Clin Sports Med. 2000;19:19-48.

24 Freedman KB, Smith AP, Romeo AA, et al. Open Bankart repair versus arthroscopic repair with transglenoid sutures or bioabsorbable tacks for recurrent anterior instability of the shoulder: A meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:1520-1527.

25 Mohtadi NGH, Bitar IJ, Sasyniuk TM, et al. Arthroscopic versus open repair for traumatic anterior shoulder instability: A meta-analysis. Arthroscopy. 2005;21:652-658.

26 Guanche CA, Quick DC, Sodergren KM, Buss DD. Arthroscopic versus open reconstruction of the shoulder in patients with isolated Bankart lesions. Am J Sports Med. 1996;24:144-148.

27 Cole BJ, L’Insalata J, Irrgang J, Warner JJP. Comparison of arthroscopic and open anterior shoulder stabilization: A two to six-year follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;82:1108-1114.

28 Fabbriciani C, Milano G, Demontis A, et al. Arthroscopic versus open treatment of Bankart lesion of the shoulder: A prospective randomized study. Arthroscopy. 2004;20:456-462.

29 Geiger DF, Hurley JA, Tovey JA, Rao JP. Results of arthroscopic versus open suture repair. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997;337:111-117.

30 Hubbell JD, Ahmad S, Bezenoff LS, et al. Comparison of shoulder stabilization using arthroscopic transglenoid sutures versus open capsulolabral repair. A 5-year minimum follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:650-654.

31 Jorgensen U, Svend-Hansen H, Bak K, Pedersen I. Recurrent post-traumatic anterior shoulder dislocation—open versus arthroscopic repair. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1999;7:118-124.

32 Kailes SB, Richmond JC. Arthroscopic vs. open Bankart reconstruction: A comparison using expected value decision analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2001;9:379-385.

33 Karlsson J, Magnusson L, Ejerhed L, et al. Comparison of open and arthroscopic stabilization for recurrent shoulder dislocation in patients with a Bankart lesion. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29:538-542.

34 Karnezis IA, Sarangi PP. Arthroscopic repair versus open surgery for shoulder instability. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83A:952.

35 Kartus J, Ejerhed L, Funck E, et al. Arthroscopic and open shoulder stabilization using absorbable implants. A clinical and radiographic comparison of two methods. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1998;6:181-188.

36 Kim SH, Ha KI, Kim SH. Bankart repair in traumatic anterior shoulder instability: Open versus arthroscopic technique. Arthroscopy. 2002;18:755-763.

37 Rhee YG, Ha JH, Cho NS. Anterior shoulder stabilization in collision athletes: Arthroscopic versus open bankart repair. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:979-985.

38 Sperber A, Hamberg P, Karlsson J, et al. Comparison of an arthroscopic and an open procedure for posttraumatic instability of the shoulder: A prospective, randomized multicenter study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;10:105-108.

39 Sperling JW, Duncan SMF, Torchia ME, et al. Bankart repair in patients aged fifty years or greater: Results of arthroscopic and open repairs. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14:111-113.

40 Steinbeck J, Jerosch J. Arthroscopic transglenoid stabilization versus open anchor suturing in traumatic anterior instability of the shoulder. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26:373-378.

41 Wang C, Ghalambor N, Zarins B, Warner JJP. Arthroscopic versus open Bankart repair: Analysis of patient subjective outcome and cost. Arthroscopy. 2005;21:1219-1222.

42 Bottoni CR, Smith EL, Berkowitz MJ, et al. Arthroscopic versus open shoulder stabilization for recurrent anterior instability: A prospective randomized clinical trial. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:1730-1737.

43 Kirkley A, Griffen S, McLintock H, Ng L. The development and evaluation of a disease-specific quality of life measurement tool for shoulder instability. The Western Ontario Shoulder Instability Index (WOSI). Am J Sports Med. 1998;26:764-772.

44 Hegedus EJ, Goode A, Campbell S, et al. Physical examination tests of the shoulder: A Systematic Review with Meta-analysis of Individual Tests. Br J Sports Med. 2008;42:80-92.

45 Tzannes A, Murrell GA. Clinical examination of the unstable shoulder. Sports Med. 2002;32:447-457.

46 Bohnsack M, Brinkmann T, Ruhman O, et al. [Open versus arthroscopic shoulder stabilization. An analysis of the treatment costs] [In German]. Orthopade. 2003;32:654-658.

47 Scheibel M, Nikulka C, Dick A, et al. Structural integrity and clinical function of the subscapularis musculotendinous unit after arthroscopic and open shoulder stabilization. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:1153-1161.

48 Slabaugh MA, Bents RT, Tokish JM, et al. Timing of return of subscapularis function in open capsular shift patients. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16:544-547.