Open Ventral Hernia Repair

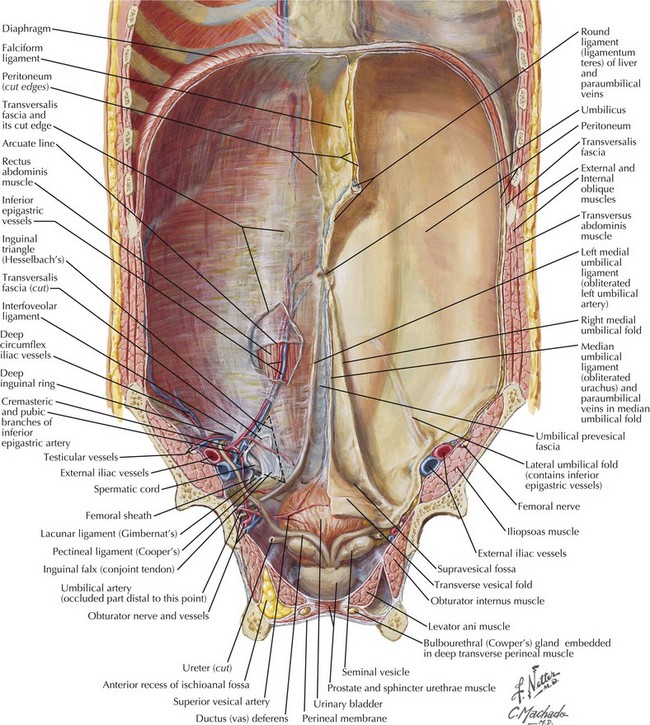

Anatomy of Abdominal Wall

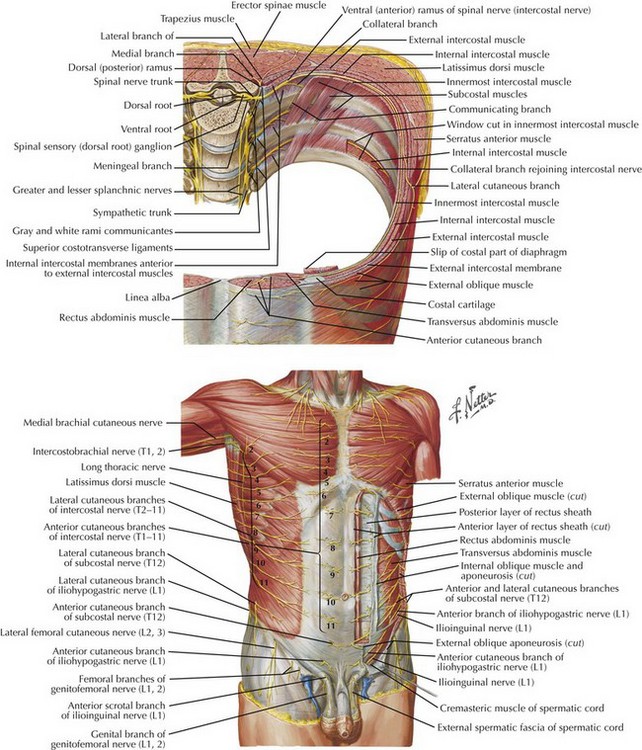

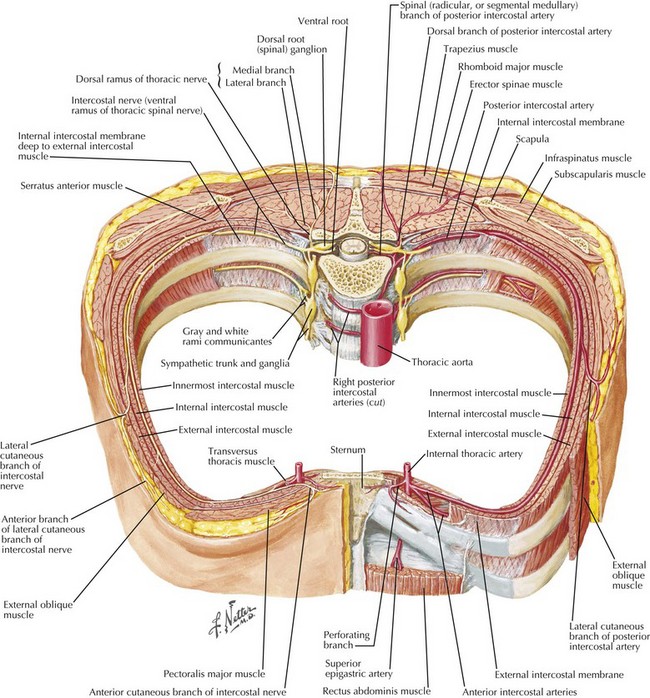

Figures 31-1 and 31-2 show the anatomy of the vascular supply and innervation of the abdominal wall. Understanding the relationships of these nerves and vessels and their location in the abdominal wall is critical to preserve them during dissection, to maintain an innervated functional abdominal wall.

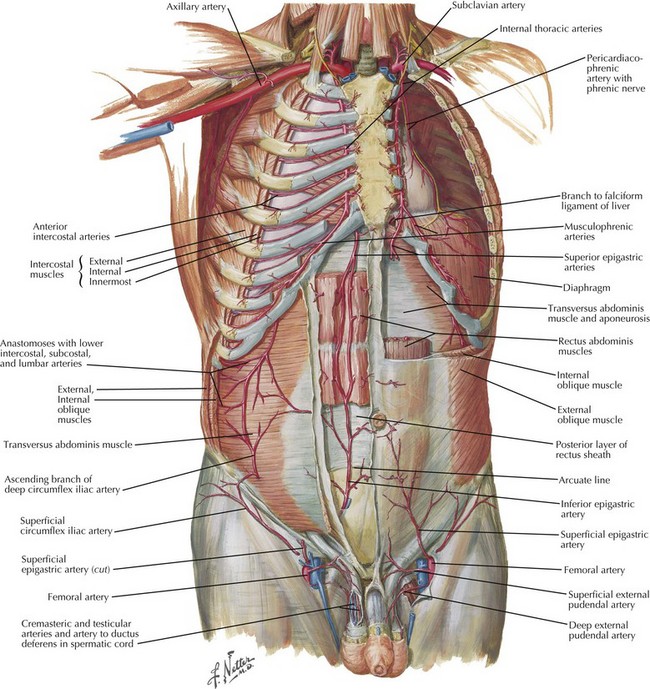

The blood supply of the anterior abdominal wall can be divided into three zones (Fig. 31-3). Zone 1 consists of the upper and midcentral abdominal wall and is supplied by the deep superior and deep inferior epigastric arteries. Zone 2 consists of the lower abdominal wall and is supplied by the epigastric arcade and the superficial inferior epigastric, superficial external pudendal, and superficial circumflex iliac arteries. Zone 3 consists of the lateral abdominal wall (flank) and is supplied by the musculophrenic and lower intercostal and lumbar arteries. Recognizing the location of prior transverse incisions that may have compromised abdominal wall blood supply is important to limit ischemic skin complications.

Surgical Technique

Creation of Retrorectus Space

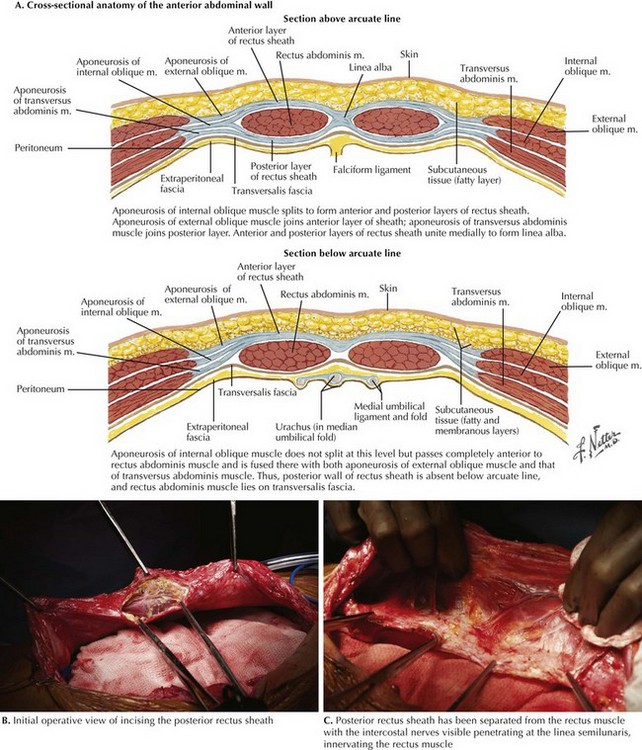

The linea alba is grasped with Kocher clamps, and the posterior rectus sheath is incised approximately 0.5 cm lateral from its edge (Fig. 31-4, A and B). This typically is begun just above the umbilicus. The plane is created using cautery, with care taken to avoid injuring the underlying rectus muscle. The retromuscular plane is then developed in a cephalad and caudal direction. The dissection is carried laterally to the linea semilunaris. This anatomic plane is localized by identifying the perforating intercostal nerves and vessels (Fig. 31-4, C). It is typically 1 cm lateral to the inferior epigastric vessels.

If the rectus muscle is relatively well preserved and sufficiently wide, the dissection is complete; the posterior components are closed and prosthetic mesh is placed. In larger hernias, requiring more overlap, or in atrophic narrowed rectus muscles, the dissection can be continued to the lateral abdominal wall (see Lateral Dissection in Preperitoneal Plane).

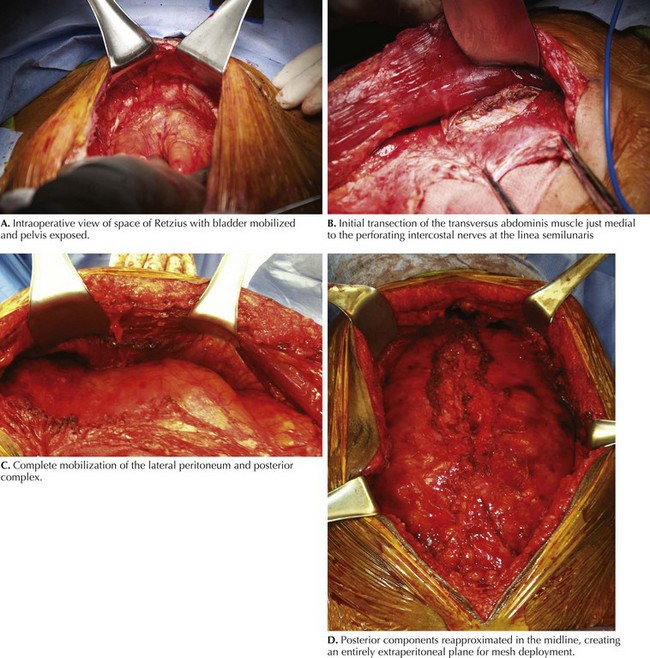

Exposure of Cooper’s Ligament and Pelvis

The dissection can be continued inferiorly to the pubis, if necessary (Figs. 31-5 and 31-6, A). The space of Retzius is entered bluntly to expose the pubic symphysis in the midline. If undissected, this plane is typically bloodless and can be easily developed. If the bladder has previously been mobilized, using a three-way Foley catheter with instillation of 300 mL of saline into the bladder can aid in identifying and avoiding a bladder injury. This plane is below the arcuate line and therefore consists of the peritoneum and transversalis fascia only. Fenestrations can occur and should be recognized and repaired accordingly. The pubis and bilateral Cooper’s (pectineal) ligament are exposed. The inferior epigastric vessels, iliac vessels, and cord structures should be identified and carefully preserved in this dissection plane.

Lateral Dissection in Preperitoneal Plane

In patients with insufficient mobilization of the posterior sheath to reapproximate in the midline, narrow atrophied rectus muscles, and inability to place wide prosthetic mesh, the dissection is carried into the lateral abdominal plane. Ideally, this plane is entered while the innervation of the rectus complex is preserved. The preperitoneal space is entered approximately 1 cm medial to the perforating nerves at the linea semilunaris (Fig. 31-6, B and C). The posterior rectus sheath is divided throughout its length. With the use of blunt Kitner dissection, the preperitoneal space is developed to the psoas muscle, if necessary. This preperitoneal plane is particularly useful for subxiphoid hernias because the peritoneum can be swept off the costal margin several centimeters superiorly. As the dissection continues cephalad, the posterior sheath typically consists of the transversus abdominis muscle. This muscle must be divided to enter the preperitoneal space.

Posterior Layer Reconstruction

Once the release is completed on both sides, the posterior components are reapproximated in the midline, completely excluding the bowel from the mesh (Fig. 31-6, D).This procedure is performed with a running absorbable suture. Defects in the posterior layer are closed with interrupted figure-of-eight sutures or buttressed with native tissue (omentum, fat). Antibiotic irrigation is typically performed.

Iqbal, CW, Pham, TH, Joseph, A, et al. Long-term outcome of 254 complex incisional hernia repairs using the modified Rives-Stoppa technique. World J Surg. 2007;31(12):2398–2404.

Luijendijk, RW, Hop, WC, van den Tol, MP, et al. A comparison of suture repair with mesh repair for incisional hernia. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(6):392–398.

Novitsky, YW, Porter, JR, Rucho, ZC, et al. Open preperitoneal retrofascial mesh repair for multiply recurrent ventral incisional hernias. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203(3):283–289.

Ramirez, OM. Inception and evolution of the components separation technique: personal recollections. Clin Plast Surg. 2006;33(2):241–246.

Stoppa, RE. The treatment of complicated groin and incisional hernias. World J Surg. 1989;13(5):545–554.