Chapter 5 Open Retromuscular Ventral Hernia Repair ![]()

1 Clinical Anatomy

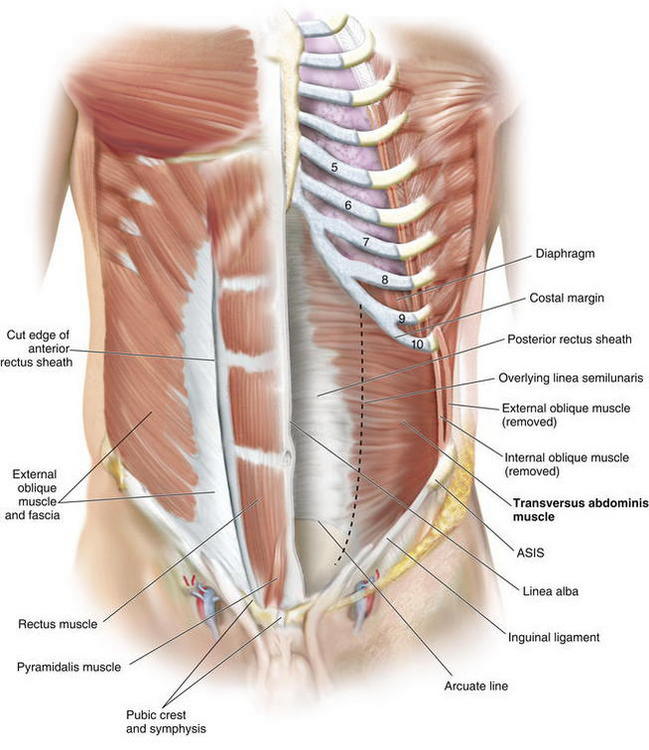

Retrorectus repair requires a thorough knowledge of the relative anatomy of the myofascial components of the abdominal wall.

Retrorectus repair requires a thorough knowledge of the relative anatomy of the myofascial components of the abdominal wall. The rectus abdominis, a long, broad, strap-like muscle, is the principal vertical muscle of the anterior abdominal wall. Its origin is at the pubic symphysis and pubic crest. The muscle is inserted into the cartilages of the fifth, sixth, and seventh ribs. The rectus abdominis is three times as wide superiorly as it is inferiorly.

The rectus abdominis, a long, broad, strap-like muscle, is the principal vertical muscle of the anterior abdominal wall. Its origin is at the pubic symphysis and pubic crest. The muscle is inserted into the cartilages of the fifth, sixth, and seventh ribs. The rectus abdominis is three times as wide superiorly as it is inferiorly. The rectus abdominis is innervated by the thoracoabdominal nerves T7-T12. The main trunks of the intercostal nerves pass anteriorly from the intercostal spaces and run between the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles in a so-called neurovascular plane. The inferior intercostal, subcostal, and lumbar arteries accompany the nerves of this plane.

The rectus abdominis is innervated by the thoracoabdominal nerves T7-T12. The main trunks of the intercostal nerves pass anteriorly from the intercostal spaces and run between the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles in a so-called neurovascular plane. The inferior intercostal, subcostal, and lumbar arteries accompany the nerves of this plane. In addition, the lateral cutaneous nerve branch of T12, as well as the ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric both enter the space between the internal oblique and transversus abdominis via the lateral border of the transversus muscle. These nerves, along with the ventral primary rami of the inferior six thoracoabdominal nerves (T7-11) innervate the anterolateral abdominal wall skin and musculature.

In addition, the lateral cutaneous nerve branch of T12, as well as the ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric both enter the space between the internal oblique and transversus abdominis via the lateral border of the transversus muscle. These nerves, along with the ventral primary rami of the inferior six thoracoabdominal nerves (T7-11) innervate the anterolateral abdominal wall skin and musculature. The rectus sheath is the strong, incomplete fibrous compartment for the rectus abdominis muscle. It forms by the fusion and separation of the aponeurosis of the lateral abdominal muscles.

The rectus sheath is the strong, incomplete fibrous compartment for the rectus abdominis muscle. It forms by the fusion and separation of the aponeurosis of the lateral abdominal muscles. At its lateral margin, the internal oblique aponeurosis splits into two layers, one passing anterior to the rectus muscle and the other passing posterior to it. The posterior layer joins with the aponeurosis of the transverse abdominis muscle to form the posterior wall of the rectus sheath. Muscle fibers of the transversus abdominis end in an aponeurosis, which contributes to the formation of the rectus sheath.

At its lateral margin, the internal oblique aponeurosis splits into two layers, one passing anterior to the rectus muscle and the other passing posterior to it. The posterior layer joins with the aponeurosis of the transverse abdominis muscle to form the posterior wall of the rectus sheath. Muscle fibers of the transversus abdominis end in an aponeurosis, which contributes to the formation of the rectus sheath. The lateral abdominal wall consists of three flat muscles: external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus abdominis. The flat muscles cross each other similar to a three-ply corset that strengthens the abdominal wall and diminishes the risk of herniation between the muscle bundles. One important consideration for the retrorectus repair is the fact that in the upper third of the abdomen, the transversus abdominis extends medially beyond the overlying linea semilunaris as a primary muscular component not as fascia (Fig. 5-1).

The lateral abdominal wall consists of three flat muscles: external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus abdominis. The flat muscles cross each other similar to a three-ply corset that strengthens the abdominal wall and diminishes the risk of herniation between the muscle bundles. One important consideration for the retrorectus repair is the fact that in the upper third of the abdomen, the transversus abdominis extends medially beyond the overlying linea semilunaris as a primary muscular component not as fascia (Fig. 5-1).2 Preoperative Considerations

Preoperative Imaging

Preoperative Imaging

I recommend routine abdominal/pelvic computed tomography (CT) imaging. CT delineates all abdominal wall defects, assessment of the integrity of the remaining abdominal wall musculature, allows for detection of previous synthetic meshes and/or occult infection, and facilitates perioperative planning. I also mandate a screening colonoscopy in appropriate patients before undertaking major abdominal wall reconstructions.

I recommend routine abdominal/pelvic computed tomography (CT) imaging. CT delineates all abdominal wall defects, assessment of the integrity of the remaining abdominal wall musculature, allows for detection of previous synthetic meshes and/or occult infection, and facilitates perioperative planning. I also mandate a screening colonoscopy in appropriate patients before undertaking major abdominal wall reconstructions. Preoperative Optimization

Preoperative Optimization

Choosing the Type of Mesh

Choosing the Type of Mesh

Use a large, synthetic mesh with or without an antiadhesive barrier. I prefer a large (30 × 30 cm) macroporous, reduced-weight polypropylene mesh.

Use a large, synthetic mesh with or without an antiadhesive barrier. I prefer a large (30 × 30 cm) macroporous, reduced-weight polypropylene mesh. Composite synthetic mesh with an antiadhesive barrier may need to be used if visceral exposure through fenestrations in the posterior layer is possible/likely.

Composite synthetic mesh with an antiadhesive barrier may need to be used if visceral exposure through fenestrations in the posterior layer is possible/likely. Biologic or biodegradable mesh should be considered in all contaminated and potentially contaminated fields. Synthetic mesh should be avoided in patients with a previous history of mesh infection, especially methicillin-resistant Staphyloccus aureus (MRSA). In addition, biologic meshes should be considered in patients with multiple comorbidities (morbid obesity, diabetes, systemic steroids or other form of immunosuppression, etc) and resultant increased risks of wound/mesh infections.

Biologic or biodegradable mesh should be considered in all contaminated and potentially contaminated fields. Synthetic mesh should be avoided in patients with a previous history of mesh infection, especially methicillin-resistant Staphyloccus aureus (MRSA). In addition, biologic meshes should be considered in patients with multiple comorbidities (morbid obesity, diabetes, systemic steroids or other form of immunosuppression, etc) and resultant increased risks of wound/mesh infections.3 Operative Steps

Planning Incision

Planning Incision

Lysis of Adhesions, Removal of Old Mesh

Lysis of Adhesions, Removal of Old Mesh

Incision of the Posterior Rectus Sheath (Rives-Stoppa-Wantz Technique)

Incision of the Posterior Rectus Sheath (Rives-Stoppa-Wantz Technique)

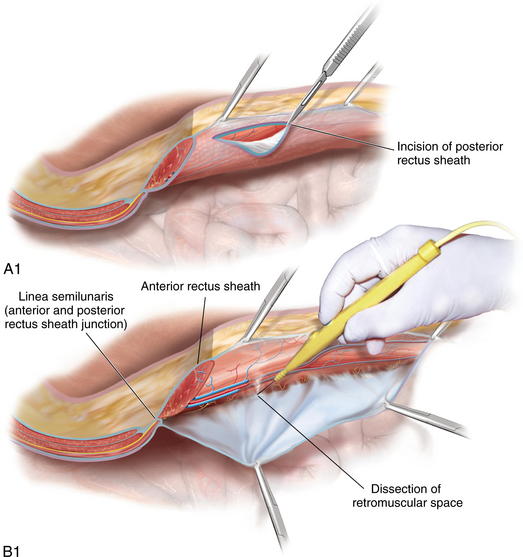

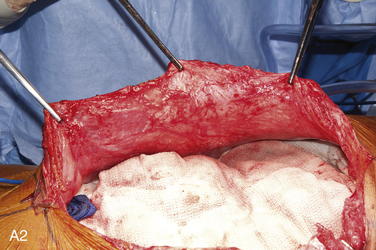

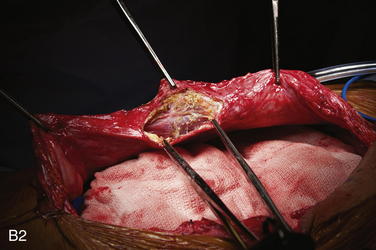

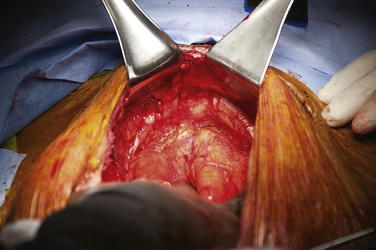

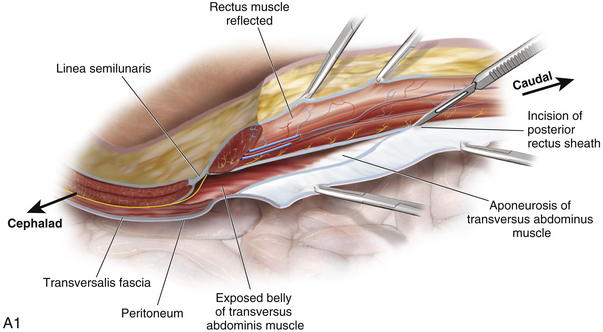

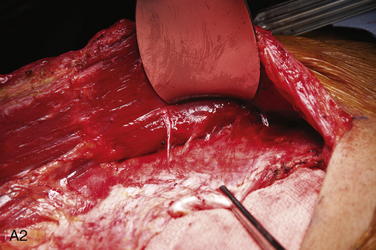

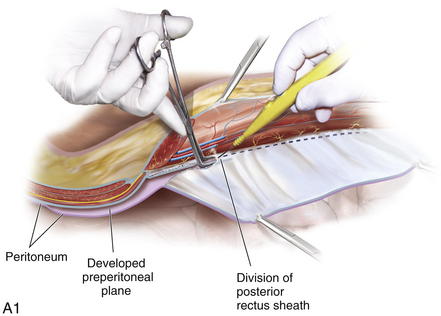

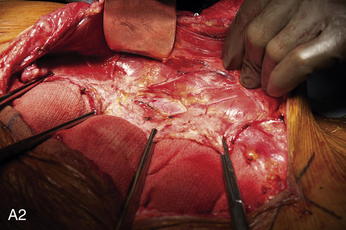

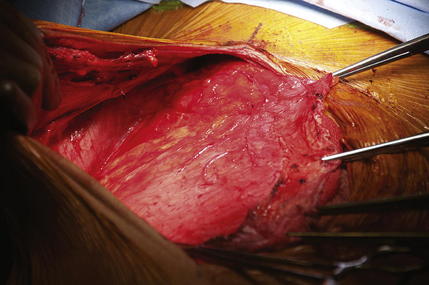

To dissect the retromuscular space to the linea semilunaris, the posterior rectus sheath is incised sharply about 0.5 cm from its edge (Fig. 5-2, A). This typically is initiated at the level of the umbilicus. The retromuscular plane is then developed using a combination of blunt dissection and electrocautery. The lateral extent of this dissection is the linea semilunaris, confirmed by visualizing the junction between the posterior and anterior rectus sheaths (Fig. 5-2, B). Careful identification of the intercostal nerves and vessels is critical to maintaining an innervated functional abdominal wall (Fig. 5-2, C).

To dissect the retromuscular space to the linea semilunaris, the posterior rectus sheath is incised sharply about 0.5 cm from its edge (Fig. 5-2, A). This typically is initiated at the level of the umbilicus. The retromuscular plane is then developed using a combination of blunt dissection and electrocautery. The lateral extent of this dissection is the linea semilunaris, confirmed by visualizing the junction between the posterior and anterior rectus sheaths (Fig. 5-2, B). Careful identification of the intercostal nerves and vessels is critical to maintaining an innervated functional abdominal wall (Fig. 5-2, C). Exposure of Cooper’s ligaments/pubis is shown in Figure 5-3. Inferiorly, the space or Retzius is entered to expose the pubis symphysis and both Cooper’s ligaments. This dissection is blunt in what is typically a bloodless plane. Since this area is below the arcuate line, posterior layer includes peritoneum and transversalis fascia only. Because both of these layers are very thin, fenestrations are not uncommon and should be repaired. Care should be taken to identify and preserve inferior epigastric vessels that course along the deep surface of the rectus muscles. The urinary bladder may be filled with saline to facilitate its identification and dissection. This is particularly prudent in patients with a previous history of pelvic surgery.

Exposure of Cooper’s ligaments/pubis is shown in Figure 5-3. Inferiorly, the space or Retzius is entered to expose the pubis symphysis and both Cooper’s ligaments. This dissection is blunt in what is typically a bloodless plane. Since this area is below the arcuate line, posterior layer includes peritoneum and transversalis fascia only. Because both of these layers are very thin, fenestrations are not uncommon and should be repaired. Care should be taken to identify and preserve inferior epigastric vessels that course along the deep surface of the rectus muscles. The urinary bladder may be filled with saline to facilitate its identification and dissection. This is particularly prudent in patients with a previous history of pelvic surgery. Exposure of the subxiphoid space is shown in Figure 5-4. The retromuscular plane can be extended cephalad to the costal margin and to the retroxiphoid/retrosternal areas.

Exposure of the subxiphoid space is shown in Figure 5-4. The retromuscular plane can be extended cephalad to the costal margin and to the retroxiphoid/retrosternal areas. Lateralization of the Dissection Plane Beyond the Linea Semilunaris

Lateralization of the Dissection Plane Beyond the Linea Semilunaris

Traditional Rives-Stoppa-Wantz dissection is carried out to the lateral edge of the rectus sheath. However, such dissection is insufficient for some patients undergoing major abdominal wall reconstructions for three main reasons: (1) insufficient medial advancement of the posterior rectus sheath, (2) decreased potential for medialization of the rectus muscles, and (3) insufficient space for large prosthetic reinforcement.

Traditional Rives-Stoppa-Wantz dissection is carried out to the lateral edge of the rectus sheath. However, such dissection is insufficient for some patients undergoing major abdominal wall reconstructions for three main reasons: (1) insufficient medial advancement of the posterior rectus sheath, (2) decreased potential for medialization of the rectus muscles, and (3) insufficient space for large prosthetic reinforcement. Three techniques for lateral extension of the retromuscular plane have been described. They are the preperitoneal, posterior component separation with intramuscular dissection, and the posterior component separation with transversus abdominis release (TAR). A description of each follows.

Three techniques for lateral extension of the retromuscular plane have been described. They are the preperitoneal, posterior component separation with intramuscular dissection, and the posterior component separation with transversus abdominis release (TAR). A description of each follows.

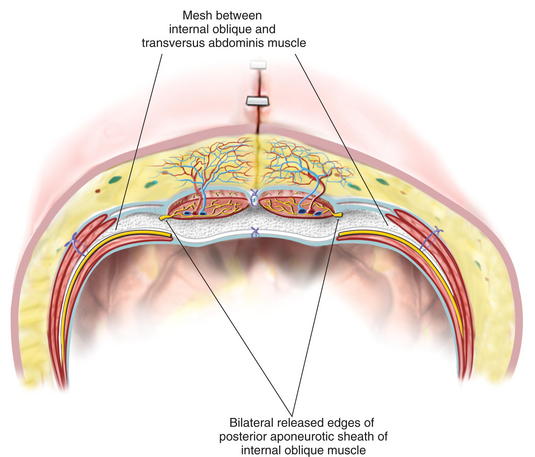

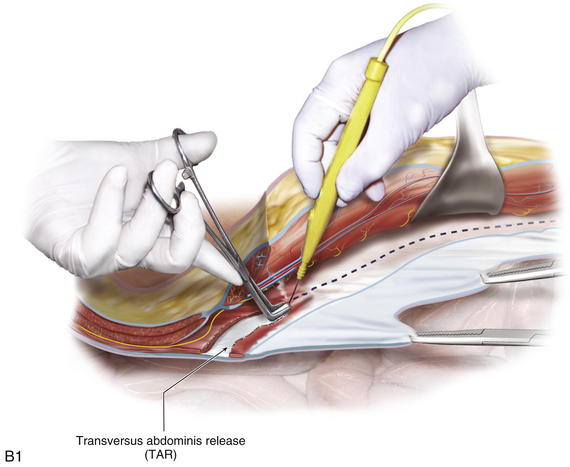

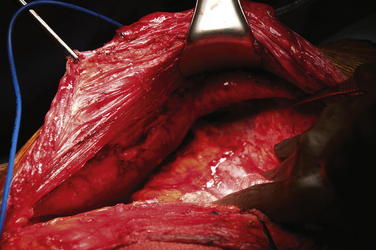

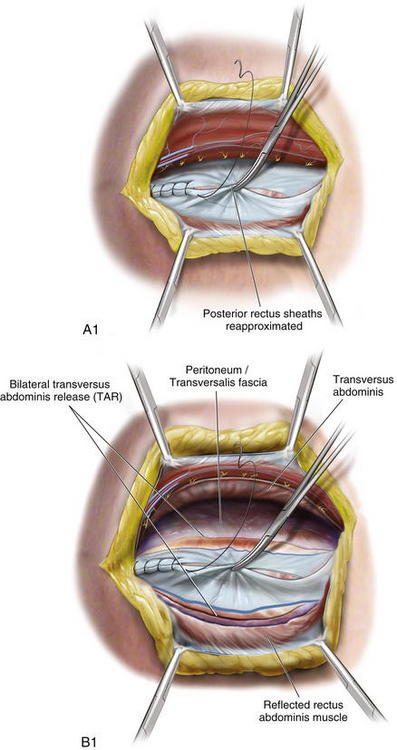

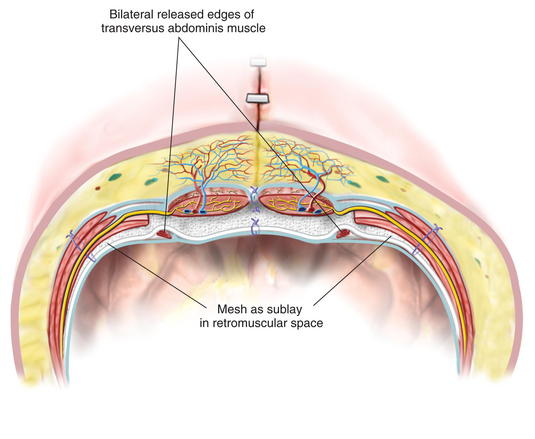

The key component to the release is the division of the entire medial edge of the transversus abdominis muscle. The main function of the transversus is to act as a “corset” around the abdomen. The synergistic action of the transversus and the posterior fibers of the internal oblique produce hoop tension through the thoracolumbar fascia. By dividing the transversus abdominis, I am able to release the circumferential muscle tension and not only provide for expansion of the abdominal cavity but also afford significant medial advancement of the posterior rectus fascia (Fig. 5-10).

The key component to the release is the division of the entire medial edge of the transversus abdominis muscle. The main function of the transversus is to act as a “corset” around the abdomen. The synergistic action of the transversus and the posterior fibers of the internal oblique produce hoop tension through the thoracolumbar fascia. By dividing the transversus abdominis, I am able to release the circumferential muscle tension and not only provide for expansion of the abdominal cavity but also afford significant medial advancement of the posterior rectus fascia (Fig. 5-10). Posterior Layer Reconstruction

Posterior Layer Reconstruction

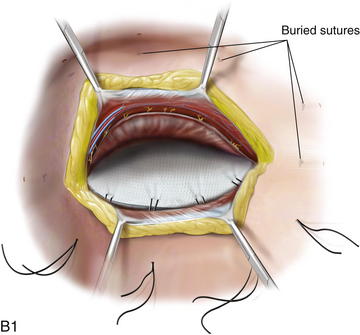

Once release is performed on both sides, the posterior rectus sheaths are reapproximated in the midline with a running monofilament suture (Fig. 5-11, A and B). Interrupted figure-of-8 sutures may be used if there is significant tension or pulmonary plateau pressures increase by 5 mm Hg or more.

Once release is performed on both sides, the posterior rectus sheaths are reapproximated in the midline with a running monofilament suture (Fig. 5-11, A and B). Interrupted figure-of-8 sutures may be used if there is significant tension or pulmonary plateau pressures increase by 5 mm Hg or more. Mesh Fixation

Mesh Fixation

The inferior edge of the mesh is secured to both Cooper’s ligament using 2 to 4 interrupted monofilament sutures. The mesh may be positioned to also reinforce both myopectineal orifices.

The inferior edge of the mesh is secured to both Cooper’s ligament using 2 to 4 interrupted monofilament sutures. The mesh may be positioned to also reinforce both myopectineal orifices. Superiorly, the mesh could be placed in beyond the costal margin and in the retroxiphoid space. It is secured with interrupted sutures around the xiphoid process. Those sutures are placed 4 to 5 cm off the edge of the mesh to allow for large overlap, especially for subxiphoid defects. Similarly, even though the mesh edge may be significantly beyond the costal margin, fixation is performed below the margin to reduce the risks of lung injury.

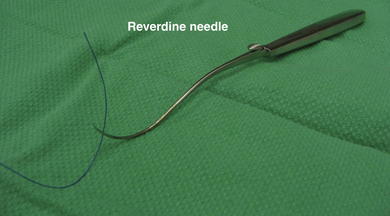

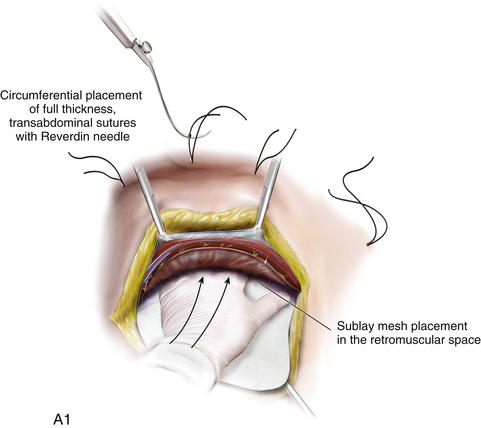

Superiorly, the mesh could be placed in beyond the costal margin and in the retroxiphoid space. It is secured with interrupted sutures around the xiphoid process. Those sutures are placed 4 to 5 cm off the edge of the mesh to allow for large overlap, especially for subxiphoid defects. Similarly, even though the mesh edge may be significantly beyond the costal margin, fixation is performed below the margin to reduce the risks of lung injury. The mesh is then fixated circumferentially with full-thickness, transabdominal sutures using the Reverdin needle (Figs. 5-13 and 5-14, A and B).

The mesh is then fixated circumferentially with full-thickness, transabdominal sutures using the Reverdin needle (Figs. 5-13 and 5-14, A and B). The mesh should be placed under appropriate “physiologic” tension. Laxity is of particular concern if biologic mesh is used because mesh “wrinkling” would lead to seromas, infections, and possible mesh degradation and/or weakening. The transfascial sutures should be placed under physiologic tension, so that when they are secured, they provide medialization of the rectus muscles. In doing so, the midline fascia is reapproximated while the mesh is taut, preventing wrinkling when closing the fascia. Alternatively, if the mesh is placed “tension free” and then the fascia is closed, the prosthetic will buckle.

The mesh should be placed under appropriate “physiologic” tension. Laxity is of particular concern if biologic mesh is used because mesh “wrinkling” would lead to seromas, infections, and possible mesh degradation and/or weakening. The transfascial sutures should be placed under physiologic tension, so that when they are secured, they provide medialization of the rectus muscles. In doing so, the midline fascia is reapproximated while the mesh is taut, preventing wrinkling when closing the fascia. Alternatively, if the mesh is placed “tension free” and then the fascia is closed, the prosthetic will buckle. Reconstruction of the Linea Alba

Reconstruction of the Linea Alba

The anterior rectus sheaths are then reapproximated in the midline to restore the linea alba. A running, slowly absorbable suture is used. Alternatively, interrupted figure-of-8 stitches can be used, especially when there is a potential predisposition to the abdominal compartment syndrome.

The anterior rectus sheaths are then reapproximated in the midline to restore the linea alba. A running, slowly absorbable suture is used. Alternatively, interrupted figure-of-8 stitches can be used, especially when there is a potential predisposition to the abdominal compartment syndrome. In rare instances when the anterior rectus sheath cannot be reapproximated, external oblique fascia release (open or endoscopic) may be performed. However, it is important to not combine the anterior external oblique release with a transversus abdominus release. If both muscle layers are released, the lateral abdominal wall can become destabilized.

In rare instances when the anterior rectus sheath cannot be reapproximated, external oblique fascia release (open or endoscopic) may be performed. However, it is important to not combine the anterior external oblique release with a transversus abdominus release. If both muscle layers are released, the lateral abdominal wall can become destabilized.4 Postoperative Care

General

General

Intraoperative hemodynamics and airway pressures affect postoperative care. Overnight intensive care unit admission is recommended for patients undergoing major abdominal wall reconstructions. Long operative times and prolonged exposure of the abdominal cavity to room air lead to significant insensible losses and predispose to large fluid shifts. As a result, patients undergoing complex abdominal wall reconstructions often remain intubated overnight. In addition, those patients with poor pulmonary reserve and/or significant increase in plateau airway pressures are kept paralyzed for 24 to 48 hours postoperatively.

Intraoperative hemodynamics and airway pressures affect postoperative care. Overnight intensive care unit admission is recommended for patients undergoing major abdominal wall reconstructions. Long operative times and prolonged exposure of the abdominal cavity to room air lead to significant insensible losses and predispose to large fluid shifts. As a result, patients undergoing complex abdominal wall reconstructions often remain intubated overnight. In addition, those patients with poor pulmonary reserve and/or significant increase in plateau airway pressures are kept paralyzed for 24 to 48 hours postoperatively. When a biologic graft is used, the drains are left in place for at least 2 weeks, regardless of the output.

When a biologic graft is used, the drains are left in place for at least 2 weeks, regardless of the output. Diet

Diet

Routine nasogastric tube decompression is reserved for patients with intestinal resections, significant intestinal manipulations, and prolonged adhesiolysis. Diet advancement is very conservative in order to avoid early postoperative bloating, retching, and vomiting, which may lead to pulmonary complications, as well as disruption of the repair. As a result, diets are not advanced until return of bowel function occurs.

Routine nasogastric tube decompression is reserved for patients with intestinal resections, significant intestinal manipulations, and prolonged adhesiolysis. Diet advancement is very conservative in order to avoid early postoperative bloating, retching, and vomiting, which may lead to pulmonary complications, as well as disruption of the repair. As a result, diets are not advanced until return of bowel function occurs.5 Outcomes

Retromuscular (Rives-Stoppa-Wantz) repair has been shown to result in an effective repair of most ventral hernias. Recurrence rates of 3% to 6% at mid- to long-term follow-ups have been reported. In fact, in 2004, given its superior track record, this approach was proclaimed to be the gold standard for open ventral hernia repair by the American Hernia Society.

Retromuscular (Rives-Stoppa-Wantz) repair has been shown to result in an effective repair of most ventral hernias. Recurrence rates of 3% to 6% at mid- to long-term follow-ups have been reported. In fact, in 2004, given its superior track record, this approach was proclaimed to be the gold standard for open ventral hernia repair by the American Hernia Society.6 Pearls and Pitfalls

1 Anatomy

Neurovascular bundles supplying rectus muscles run in between transversus abdominis and internal oblique muscles and traverse posterior rectus sheath near the linea semilunaris, entering rectus muscle at its lateral edge. Care should be taken to identify and preserve these nerve bundles during the retrorectus dissection to prevent denervation of the rectus muscles

Neurovascular bundles supplying rectus muscles run in between transversus abdominis and internal oblique muscles and traverse posterior rectus sheath near the linea semilunaris, entering rectus muscle at its lateral edge. Care should be taken to identify and preserve these nerve bundles during the retrorectus dissection to prevent denervation of the rectus muscles2 Preoperative Considerations

3 Intraoperative Considerations

4 Technical Considerations

In many patients, retromuscular dissection to the extent of the lateral edge of both rectus sheaths may be sufficient.

In many patients, retromuscular dissection to the extent of the lateral edge of both rectus sheaths may be sufficient. Release of the posterior rectus sheath (posterior component separation) could be achieved with or without transversus abdominis muscle release. Posterior component separations should NOT be combined with any type of the anterior release. Traditional retrorectus dissection, on the other hand, could be an excellent adjunct to the anterior (external oblique) release to allow for sublay mesh placement.

Release of the posterior rectus sheath (posterior component separation) could be achieved with or without transversus abdominis muscle release. Posterior component separations should NOT be combined with any type of the anterior release. Traditional retrorectus dissection, on the other hand, could be an excellent adjunct to the anterior (external oblique) release to allow for sublay mesh placement. If posterior rectus sheaths cannot be re-approximated, omentum, remnants of the hernia sac, or an absorbable mesh can be used to “bridge” the gap.

If posterior rectus sheaths cannot be re-approximated, omentum, remnants of the hernia sac, or an absorbable mesh can be used to “bridge” the gap. Complete exclusion of the abdominal viscera is essential to both avoid intestinal herniations/strangulations through defects in the posterior layer of reconstruction and to avoid intestinal exposure to uncoated synthetic meshes.

Complete exclusion of the abdominal viscera is essential to both avoid intestinal herniations/strangulations through defects in the posterior layer of reconstruction and to avoid intestinal exposure to uncoated synthetic meshes. The mesh should be sized to provide significant reinforcement of the whole visceral sac. Typically, at least a 30 × 30 cm synthetic or a 20 × 20 cm biologic mesh is used.

The mesh should be sized to provide significant reinforcement of the whole visceral sac. Typically, at least a 30 × 30 cm synthetic or a 20 × 20 cm biologic mesh is used. Mesh fixation is performed with a wide lateral overlap. Full-thickness transabdominal sutures are used to fixate the mesh and to provide physiologic tension across the entire abdominal wall. “Tension-free” repair of the abdominal wall is not adequate if preservation of the abdominal wall function is intended.

Mesh fixation is performed with a wide lateral overlap. Full-thickness transabdominal sutures are used to fixate the mesh and to provide physiologic tension across the entire abdominal wall. “Tension-free” repair of the abdominal wall is not adequate if preservation of the abdominal wall function is intended.Carbonell A.M., Cobb W.S., Chen S.M. Posterior components separation during retromuscular hernia repair. Hernia. 2008;12(4):359-362.

Conze J., Prescher A., Klinge U., et al. Pitfalls in retromuscular mesh repair for incisional hernia: the importance of the “fatty triangle. Hernia. 2004;8(3):255-259.

Hammond D.L., Ackerman L., Holdsworth R., Elzey B. Effects of spinal nerve ligation on immunohistochemically identified neurons in the L4 and L5 dorsal root ganglia of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 2004;475(4):575-589.

Iqbal C.W., Pham T.H., Joseph A., et al. Long-term outcome of 254 complex incisional hernia repairs using the modified Rives-Stoppa technique. World J Surg. 2007;31(12):2398-2404.

Novitsky Y.W., Porter J.R., Rucho Z.C., et al. Open preperitoneal retrofascial mesh repair for multiply recurrent ventral incisional hernias. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203(3):283-289.

Rives J., Pire J.C., Flament J.B., et al. [Treatment of large eventrations. New therapeutic indications apropos of 322 cases]. Chirurgie. 1985;111(3):215-225.

Rosen MJ, Fatima J, Sarr MG: Repair of abdominal wall hernias with restoration of abdominal wall function. J Gastrointest Surg 14(1):175–185.

Stoppa R.E. The treatment of complicated groin and incisional hernias. World J Surg. 1989;13(5):545-554.

Wirhed R. Athletic Ability & the Anatomy of Motion. Wolfe Medical Publications Ltd; 1984.