Chapter 7 Open Repair of Parastomal Hernias ![]()

2 Clinical Anatomy

1 Dissection Planes

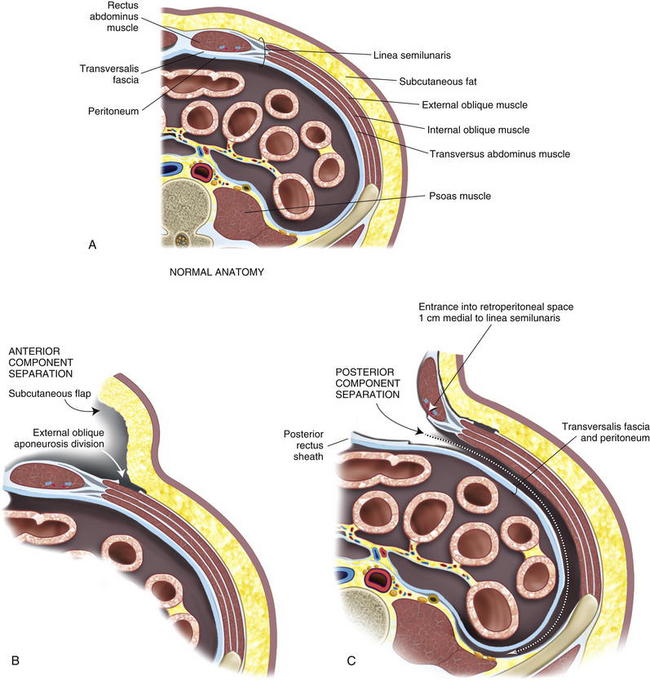

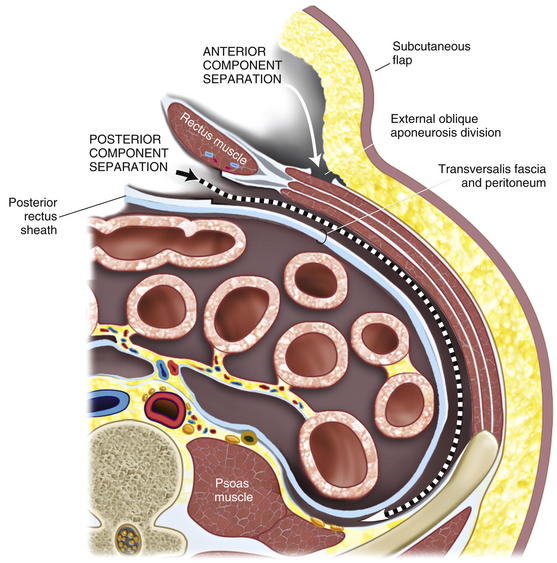

Abdominal wall anatomy is discussed in detail in Chapter 1. It is essential to understand the anatomic layering of the abdominal wall for proper retrorectus/retroperitoneal mesh placement and anterior component separation.

Abdominal wall anatomy is discussed in detail in Chapter 1. It is essential to understand the anatomic layering of the abdominal wall for proper retrorectus/retroperitoneal mesh placement and anterior component separation. The linea semilunaris lies at the lateral aspect of the posterior rectus sheath. Rectus innervation is preserved and plane development is facilitated by entrance into the retroperitoneal space medial to the linea semilunaris. Dissection in the retroperitoneal space is below the transversus abdominis muscle and can be completed to the psoas. Mesh placement is in this retroperitoneal space.

The linea semilunaris lies at the lateral aspect of the posterior rectus sheath. Rectus innervation is preserved and plane development is facilitated by entrance into the retroperitoneal space medial to the linea semilunaris. Dissection in the retroperitoneal space is below the transversus abdominis muscle and can be completed to the psoas. Mesh placement is in this retroperitoneal space.2 Ostomy Site Selection

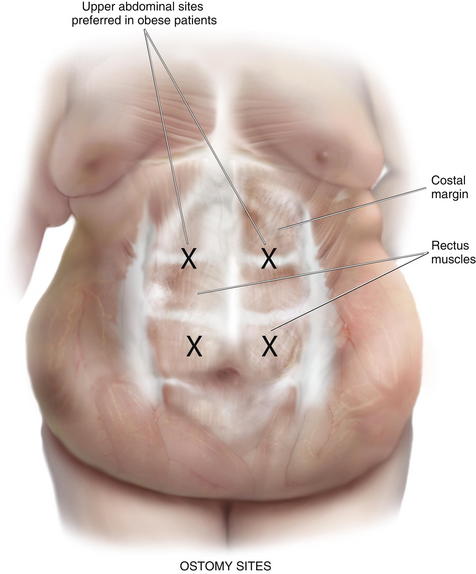

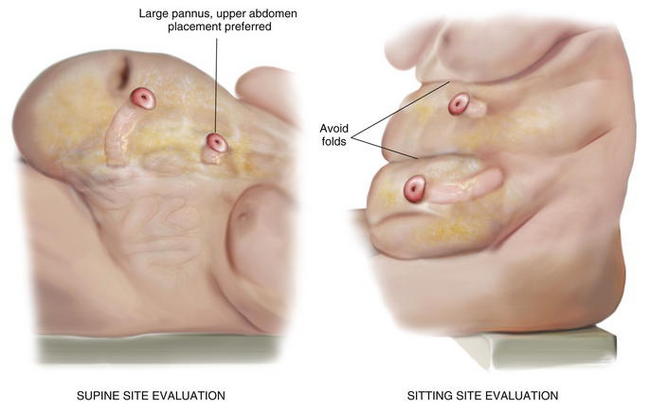

Ostomy sites are chosen with the assistance of an enterostomal therapist and are marked preoperatively. Patients should be examined while sitting and supine, and an appropriate location visible to the patient is found. Transrectus placement is typically preferred. Folds should be avoided to facilitate appliance adhesion. Thus, it is essential to examine the patient while he or she is sitting in order to visualize folds. Obese patients with a significant pannus should be sited in the upper abdomen. During complex abdominal wall reconstruction, excess skin and subcutaneous tissues are often resected, and therefore consideration must be given to the eventual placement of the stoma (Figs. 7-2 and 7-3).

Ostomy sites are chosen with the assistance of an enterostomal therapist and are marked preoperatively. Patients should be examined while sitting and supine, and an appropriate location visible to the patient is found. Transrectus placement is typically preferred. Folds should be avoided to facilitate appliance adhesion. Thus, it is essential to examine the patient while he or she is sitting in order to visualize folds. Obese patients with a significant pannus should be sited in the upper abdomen. During complex abdominal wall reconstruction, excess skin and subcutaneous tissues are often resected, and therefore consideration must be given to the eventual placement of the stoma (Figs. 7-2 and 7-3).3 Preoperative Considerations

1 Comorbidities

Appropriate patient selection and optimization is essential. The procedure results in a significant physiologic insult. An extended operation with a long midline incision and prolonged adhesiolysis is typical. Significant fluid shifts should be expected. Those with extensive cardiac, pulmonary, or renal disease should be vetted carefully and optimized maximally. Risk of surgery may be prohibitive in some.

Appropriate patient selection and optimization is essential. The procedure results in a significant physiologic insult. An extended operation with a long midline incision and prolonged adhesiolysis is typical. Significant fluid shifts should be expected. Those with extensive cardiac, pulmonary, or renal disease should be vetted carefully and optimized maximally. Risk of surgery may be prohibitive in some. Combined ventral and parastomal hernias are typical. With large hernias there may be significant loss of abdominal domain. Intraabdominal reduction results in increased abdominal compartment pressures with potential for pulmonary and renal compromise. The use of a large biologic mesh prosthesis partially mitigates this problem; however, perioperative intensive care including brief ventilator support is not unusual.

Combined ventral and parastomal hernias are typical. With large hernias there may be significant loss of abdominal domain. Intraabdominal reduction results in increased abdominal compartment pressures with potential for pulmonary and renal compromise. The use of a large biologic mesh prosthesis partially mitigates this problem; however, perioperative intensive care including brief ventilator support is not unusual. Timing of the operation is important as well. An appropriate interval from previous surgeries should be allowed. This typically should be a minimum of 3 months. However, with a history of a significant inflammatory process or hostile abdomen on previous exploration, a longer interval (6 months to a year) may be appropriate. On exam before exploration, ideally, the abdominal skin overlying any midline hernia should be mobile and soft without significant adherence to underlying bowel loops.

Timing of the operation is important as well. An appropriate interval from previous surgeries should be allowed. This typically should be a minimum of 3 months. However, with a history of a significant inflammatory process or hostile abdomen on previous exploration, a longer interval (6 months to a year) may be appropriate. On exam before exploration, ideally, the abdominal skin overlying any midline hernia should be mobile and soft without significant adherence to underlying bowel loops. Those that present with infected prosthetic mesh with or without fistulas are particularly good candidates for this approach. The duration and complexity of operation can be expected to increase significantly in this situation.

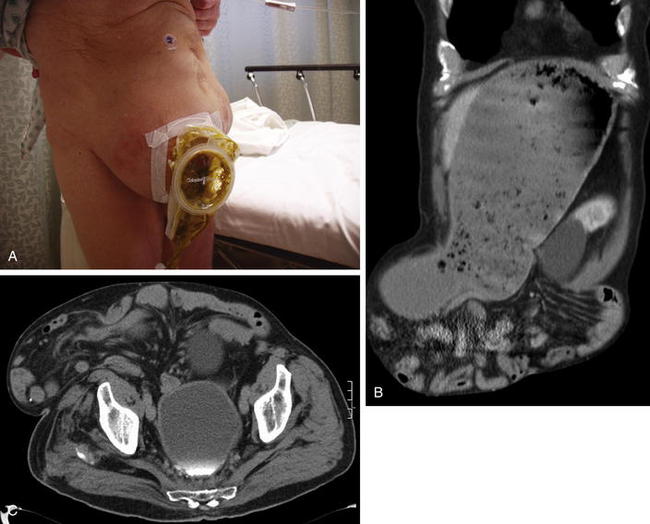

Those that present with infected prosthetic mesh with or without fistulas are particularly good candidates for this approach. The duration and complexity of operation can be expected to increase significantly in this situation. Preoperative imaging with abdominal pelvic computed tomography (CT) scans is routinely performed. These images provide important information as to the exact location of the stoma in the abdominal wall, the integrity of the rectus muscle and lateral abdominal wall musculature, and the size of the parastomal and midline hernias. In addition, the surgeon can be alerted to possible loss of abdominal domain and plan appropriately.

Preoperative imaging with abdominal pelvic computed tomography (CT) scans is routinely performed. These images provide important information as to the exact location of the stoma in the abdominal wall, the integrity of the rectus muscle and lateral abdominal wall musculature, and the size of the parastomal and midline hernias. In addition, the surgeon can be alerted to possible loss of abdominal domain and plan appropriately.2 Two-Team Approach

We have found a two-team approach particularly efficacious. One team focuses on adhesiolysis, intestinal mobilization, resection, and repair as appropriate. A second team proceeds with abdominal wall reconstruction. In our institution, we typically use a colorectal surgical team and a general surgical team. Although, one surgeon can certainly accomplish these procedures, fatigue of the operating team does become a factor with operative times averaging about 5 hours. A planned two-team approach helps facilitate procedure progression in these prolonged cases.

We have found a two-team approach particularly efficacious. One team focuses on adhesiolysis, intestinal mobilization, resection, and repair as appropriate. A second team proceeds with abdominal wall reconstruction. In our institution, we typically use a colorectal surgical team and a general surgical team. Although, one surgeon can certainly accomplish these procedures, fatigue of the operating team does become a factor with operative times averaging about 5 hours. A planned two-team approach helps facilitate procedure progression in these prolonged cases.3 Operative Options

Multiple methods of parastomal hernia repair, both laparoscopic and open, have been described. The multiplicity of procedures belies the complex nature of the problem and the lack of a clear and simple, yet efficacious repair.

Multiple methods of parastomal hernia repair, both laparoscopic and open, have been described. The multiplicity of procedures belies the complex nature of the problem and the lack of a clear and simple, yet efficacious repair. Direct suture repair has been frequently described but has an unacceptably high recurrence rate. Mesh, either biologic or synthetic, placed in a subcutaneous overlay, or in a retrorectus underlay has been described with variable results. Stomal transposition with or without mesh use has been used also, and results have also been variable.

Direct suture repair has been frequently described but has an unacceptably high recurrence rate. Mesh, either biologic or synthetic, placed in a subcutaneous overlay, or in a retrorectus underlay has been described with variable results. Stomal transposition with or without mesh use has been used also, and results have also been variable.4 Operation Steps

1 Midline Laparotomy

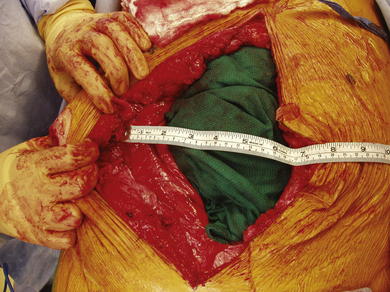

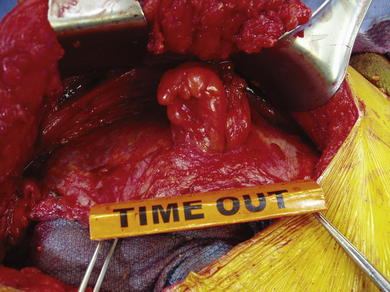

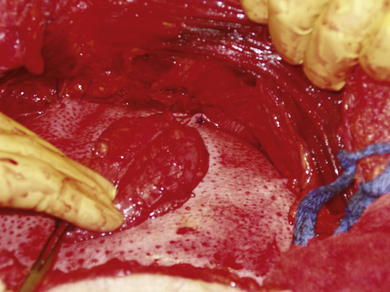

After preoperative bowel preparation, deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis, and intravenous antibiotics, the patient is approached through a midline laparotomy. Patients are placed in low lithotomy with Allen stirrups or Yellow Fin stirrups to allow easy access to the pelvis for adhesiolysis. The stoma is isolated and excluded with an impervious iodine impregnated sticky drape. Midline entry can be challenging in those with a previously placed mesh prostheses, which is commonly seen after previous attempts at repair. The previous scar is excised, fistulas are mobilized, and mesh is explanted. Particularly careful and tedious dissection is necessary to prevent enterotomy (Fig. 7-4).

After preoperative bowel preparation, deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis, and intravenous antibiotics, the patient is approached through a midline laparotomy. Patients are placed in low lithotomy with Allen stirrups or Yellow Fin stirrups to allow easy access to the pelvis for adhesiolysis. The stoma is isolated and excluded with an impervious iodine impregnated sticky drape. Midline entry can be challenging in those with a previously placed mesh prostheses, which is commonly seen after previous attempts at repair. The previous scar is excised, fistulas are mobilized, and mesh is explanted. Particularly careful and tedious dissection is necessary to prevent enterotomy (Fig. 7-4).2 Complete Adhesiolysis and Stomal Mobilization

A complete adhesiolysis is undertaken to the root of the mesentery. It is essential to fully free the abdominal wall to allow complete mobility of the wall for reconstruction. The bowel proximal to the stoma is typically divided with a linear cutter intraabdominally, isolating the stoma to limit contamination. The mucocutaneous junction is then taken down, and the old stoma is excised. The intestinal segment used for the stoma is mobilized adequately to transpose it, preferably to the contralateral side. The ventral and parastomal hernia defect size is assessed, and a decision is made as to whether component separation will be necessary.

A complete adhesiolysis is undertaken to the root of the mesentery. It is essential to fully free the abdominal wall to allow complete mobility of the wall for reconstruction. The bowel proximal to the stoma is typically divided with a linear cutter intraabdominally, isolating the stoma to limit contamination. The mucocutaneous junction is then taken down, and the old stoma is excised. The intestinal segment used for the stoma is mobilized adequately to transpose it, preferably to the contralateral side. The ventral and parastomal hernia defect size is assessed, and a decision is made as to whether component separation will be necessary.3 Anterior Component Separation

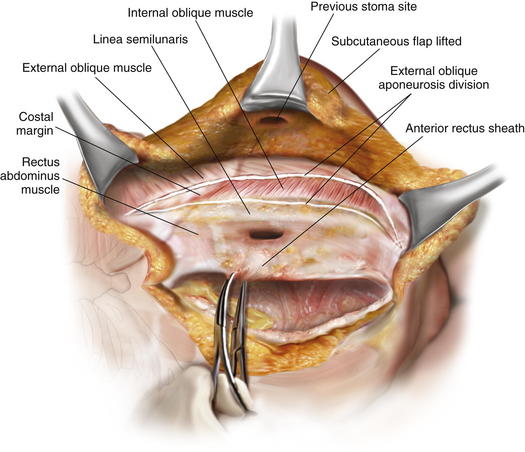

An open component separation technique is preferred for the old stoma site. This allows mobilization of a subcutaneous skin flap including the old stoma site. The skin flap is mobilized at least 2 cm lateral to the rectus sheath, and the external oblique aponeurosis is identified. The external oblique aponeurosis is opened from above the costal margin to the pelvis. In some cases, there may be enough redundant skin with this flap to allow complete resection of the skin and subcutaneous tissue containing the old stoma site after abdominal wall reconstruction. The fascial edges are assessed to see if closure will be feasible anteriorly. If deemed necessary to gain additional anterior abdominal wall mobilization, a contralateral anterior component separation is performed, either by lifting a flap or proceeding with an endoscopic technique, which we prefer for the side opposite the stoma. The endoscopic technique preserves the perforators to the abdominal wall skin and avoids a large skin flap around the new stoma, as described in Chapter 11 (Figs 7-5 and 7-6).

An open component separation technique is preferred for the old stoma site. This allows mobilization of a subcutaneous skin flap including the old stoma site. The skin flap is mobilized at least 2 cm lateral to the rectus sheath, and the external oblique aponeurosis is identified. The external oblique aponeurosis is opened from above the costal margin to the pelvis. In some cases, there may be enough redundant skin with this flap to allow complete resection of the skin and subcutaneous tissue containing the old stoma site after abdominal wall reconstruction. The fascial edges are assessed to see if closure will be feasible anteriorly. If deemed necessary to gain additional anterior abdominal wall mobilization, a contralateral anterior component separation is performed, either by lifting a flap or proceeding with an endoscopic technique, which we prefer for the side opposite the stoma. The endoscopic technique preserves the perforators to the abdominal wall skin and avoids a large skin flap around the new stoma, as described in Chapter 11 (Figs 7-5 and 7-6).4 Retrorectus Mobilization

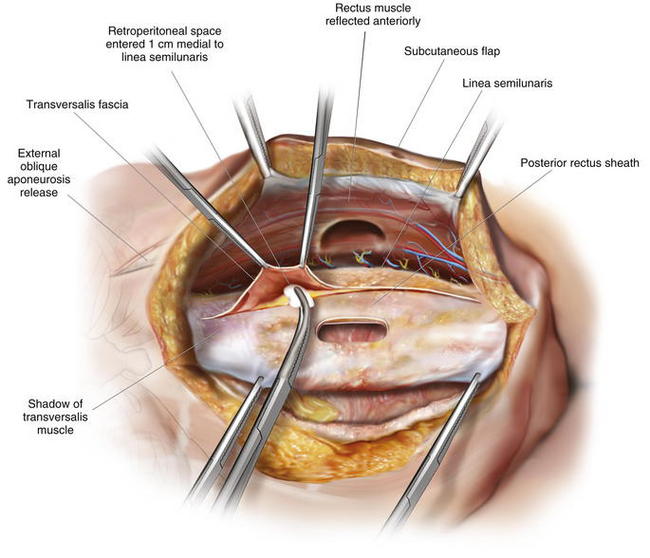

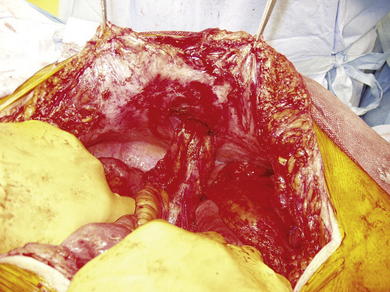

The rectus sheath is now entered in the midline, and the muscle is mobilized anteriorly, allowing visualization of the posterior rectus sheath and the linea semilunaris laterally. This space can be difficult to access with a prior stoma. However, if one dissects above and below the old stoma site, the space can almost always be recreated. The parastomal hernia sac can be left in situ on the posterior rectus sheath if possible, although this is often difficult. Alternatively, the hole created in the posterior rectus sheath at the old stoma site can be reapproximated with sutures. One of the limits of the posterior rectus sheath is the lateral extent of mesh placement. For standard midline defects, this is often not a significant problem. For parastomal defects or when reinforcing new stomas, creating space for lateral overlap and fixation of the mesh can be difficult. Utilizing the preperitoneal dissection plane in the lateral abdominal wall, large sheets of mesh can be utilized to reinforce the old stoma site and the newly created stoma. To access this plane, the posterior rectus sheath is superficially opened approximately 1 cm medial to the linea semilunaris, and the retroperitoneal space is entered, posterior to the transversus abdominis muscle. By opening medial to the linea semilunaris, injury to the segmental intercostal nerves innervating the rectus is less likely. The dissection is continued laterally in the retroperitoneal space to the psoas muscles from the costal margin to the pelvis. This dissection is completed on the opposite side as well. It is more difficult on the side of the previous stoma, but with care, full mobilization can be accomplished, preserving the posterior sheath and the peritoneum laterally for closure over the bowel before mesh placement (Figs. 7-7 to 7-9).

The rectus sheath is now entered in the midline, and the muscle is mobilized anteriorly, allowing visualization of the posterior rectus sheath and the linea semilunaris laterally. This space can be difficult to access with a prior stoma. However, if one dissects above and below the old stoma site, the space can almost always be recreated. The parastomal hernia sac can be left in situ on the posterior rectus sheath if possible, although this is often difficult. Alternatively, the hole created in the posterior rectus sheath at the old stoma site can be reapproximated with sutures. One of the limits of the posterior rectus sheath is the lateral extent of mesh placement. For standard midline defects, this is often not a significant problem. For parastomal defects or when reinforcing new stomas, creating space for lateral overlap and fixation of the mesh can be difficult. Utilizing the preperitoneal dissection plane in the lateral abdominal wall, large sheets of mesh can be utilized to reinforce the old stoma site and the newly created stoma. To access this plane, the posterior rectus sheath is superficially opened approximately 1 cm medial to the linea semilunaris, and the retroperitoneal space is entered, posterior to the transversus abdominis muscle. By opening medial to the linea semilunaris, injury to the segmental intercostal nerves innervating the rectus is less likely. The dissection is continued laterally in the retroperitoneal space to the psoas muscles from the costal margin to the pelvis. This dissection is completed on the opposite side as well. It is more difficult on the side of the previous stoma, but with care, full mobilization can be accomplished, preserving the posterior sheath and the peritoneum laterally for closure over the bowel before mesh placement (Figs. 7-7 to 7-9).5 Stoma Site Transposition and Posterior Sheath Closure

The previous stoma site in the posterior sheath is closed with a long-term absorbable suture, and the stoma is brought through the posterior sheath on the contralateral side at a site corresponding to the point marked on the skin preoperatively by the enterostomal therapist. In order to establish the appropriate track for the new stoma, it is important to bring all layers of the component separated abdominal wall together in the midline simulating the recreated linea alba. Skin, anterior sheath, rectus muscle, and posterior sheath must all be aligned as the new ostomy aperture is created to ensure that there is no angulation through any layer that could potentially obstruct the stoma. We typically create a circular defect in the skin, sized appropriately for the intestinal diameter. The defect in the rectus sheath and the rectus muscle is created longitudinally and is typically at least two finger breadths in size, again sized appropriately for intestinal diameter. The intestinal segment for the stoma is then brought through the posterior sheath only at this time. The posterior sheath is closed in the midline, completely covering all intestine, except the segment brought up for the new stoma.

The previous stoma site in the posterior sheath is closed with a long-term absorbable suture, and the stoma is brought through the posterior sheath on the contralateral side at a site corresponding to the point marked on the skin preoperatively by the enterostomal therapist. In order to establish the appropriate track for the new stoma, it is important to bring all layers of the component separated abdominal wall together in the midline simulating the recreated linea alba. Skin, anterior sheath, rectus muscle, and posterior sheath must all be aligned as the new ostomy aperture is created to ensure that there is no angulation through any layer that could potentially obstruct the stoma. We typically create a circular defect in the skin, sized appropriately for the intestinal diameter. The defect in the rectus sheath and the rectus muscle is created longitudinally and is typically at least two finger breadths in size, again sized appropriately for intestinal diameter. The intestinal segment for the stoma is then brought through the posterior sheath only at this time. The posterior sheath is closed in the midline, completely covering all intestine, except the segment brought up for the new stoma.6 Reapproximation of Previous Stoma Site in Anterior Sheath and Retrorectus Placement of Biologic Mesh

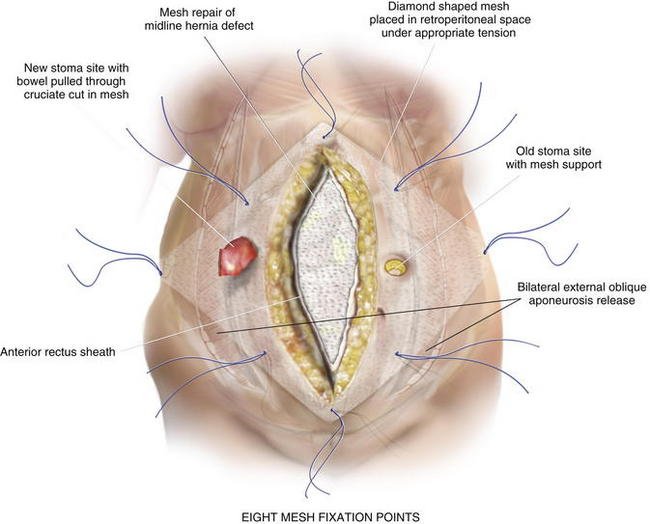

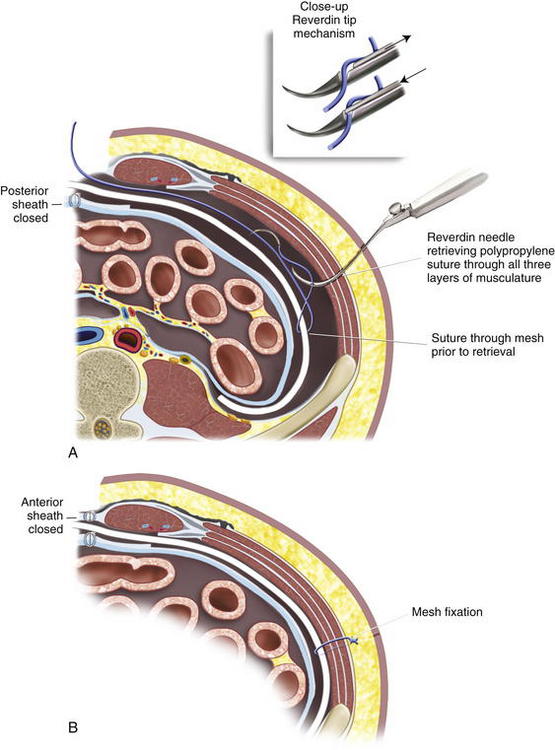

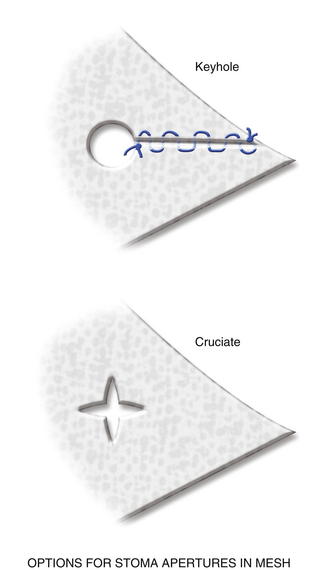

The previous stoma site is closed in the anterior sheath with long-term absorbable suture. Typically, a 20 × 20 cm sheet of biologic mesh is used and positioned in a diamond shaped configuration in the retrorectus and retroperitoneal spaces. The mesh is secured cephalad and caudad initially with two #1 polypropylene sutures brought through the abdominal wall through skin stab incisions with the Reverdin needle. The mesh is then secured laterally on the side opposite the new stoma, initially with three heavy polypropylene sutures brought transabdominally through the skin stab incisions in the same manner with the Reverdin needle. Keyholes are made in the mesh for passage of the stoma, and the stoma is pulled through; the mesh is resecured with a polypropylene suture laterally to keep the soft biologic mesh just adjacent to the stoma. More recently we have been making a cruciate incision in the mesh and pulling the stoma through instead of using keyholes. A small gap of about one finger breadth is allowed adjacent to the stoma to prevent constriction at the mesh level. Again, importantly the hole in the mesh must be made to align with the hole previously made in the posterior sheath. If the rectus muscle, anterior sheath, and skin apertures are not already created, the rectus, anterior fascia, and skin are now pulled toward the midline, so one can determine where a properly aligned aperture can be made for the new stoma site through the remaining abdominal wall. This aperture should be made while simulating the linea alba, reapproximated in the midline. An appropriately sized circle of skin is excised, and a longitudinal, muscle-splitting incision is made in the anterior rectus sheath and rectus muscle. The ostomy is then pulled up through the mesh only. The mesh is then secured in the retrorectus and retroperitoneal spaces to the abdominal wall via three skin stab incisions just as it was on the opposite side (Figs. 7-12 to 7-16).

The previous stoma site is closed in the anterior sheath with long-term absorbable suture. Typically, a 20 × 20 cm sheet of biologic mesh is used and positioned in a diamond shaped configuration in the retrorectus and retroperitoneal spaces. The mesh is secured cephalad and caudad initially with two #1 polypropylene sutures brought through the abdominal wall through skin stab incisions with the Reverdin needle. The mesh is then secured laterally on the side opposite the new stoma, initially with three heavy polypropylene sutures brought transabdominally through the skin stab incisions in the same manner with the Reverdin needle. Keyholes are made in the mesh for passage of the stoma, and the stoma is pulled through; the mesh is resecured with a polypropylene suture laterally to keep the soft biologic mesh just adjacent to the stoma. More recently we have been making a cruciate incision in the mesh and pulling the stoma through instead of using keyholes. A small gap of about one finger breadth is allowed adjacent to the stoma to prevent constriction at the mesh level. Again, importantly the hole in the mesh must be made to align with the hole previously made in the posterior sheath. If the rectus muscle, anterior sheath, and skin apertures are not already created, the rectus, anterior fascia, and skin are now pulled toward the midline, so one can determine where a properly aligned aperture can be made for the new stoma site through the remaining abdominal wall. This aperture should be made while simulating the linea alba, reapproximated in the midline. An appropriately sized circle of skin is excised, and a longitudinal, muscle-splitting incision is made in the anterior rectus sheath and rectus muscle. The ostomy is then pulled up through the mesh only. The mesh is then secured in the retrorectus and retroperitoneal spaces to the abdominal wall via three skin stab incisions just as it was on the opposite side (Figs. 7-12 to 7-16).7 Reapproximation of Midline Anterior Fascia over Mesh, Pull Through of Stoma

The stoma is now pulled through the rectus muscle, anterior sheath, and skin. Two 10-mm flat closed suction drains are brought out through the inferior abdominal wall through stab incisions just above the mesh. The midline fascia is closed with a heavy #1 long-term absorbable suture over the biologic mesh (Fig. 7-17).

The stoma is now pulled through the rectus muscle, anterior sheath, and skin. Two 10-mm flat closed suction drains are brought out through the inferior abdominal wall through stab incisions just above the mesh. The midline fascia is closed with a heavy #1 long-term absorbable suture over the biologic mesh (Fig. 7-17).5 Postoperative Care

Patients with larger hernias and any loss of abdominal domain are typically observed in the intensive care unit immediately postoperatively. Careful monitoring of pulmonary and fluid status is essential in these patients. Drains are typically maintained for 2 weeks, then discontinued. Antibiotics are stopped at 24 hours, and they are not continued for the duration of the drains unless signs of superficial infections are present.

Patients with larger hernias and any loss of abdominal domain are typically observed in the intensive care unit immediately postoperatively. Careful monitoring of pulmonary and fluid status is essential in these patients. Drains are typically maintained for 2 weeks, then discontinued. Antibiotics are stopped at 24 hours, and they are not continued for the duration of the drains unless signs of superficial infections are present. Early respiratory difficulties and renal difficulties related to loss of domain and resuscitation can be seen. In an early series of 12 patients, we had one early postoperative death, but the cause was unclear because the family refused postmortem examination. Thirty-three percent had significant perioperative complications, including one transient renal failure requiring hemodialysis, one who acutely thrombosed an aortobifemoral graft, and one wound infection requiring local care. We have not had to explant any mesh. No symptomatic recurrences were noted in our 11 patients at 1 year. CT follow-up was obtained in all, and two small recurrences were noted radiographically only.

Early respiratory difficulties and renal difficulties related to loss of domain and resuscitation can be seen. In an early series of 12 patients, we had one early postoperative death, but the cause was unclear because the family refused postmortem examination. Thirty-three percent had significant perioperative complications, including one transient renal failure requiring hemodialysis, one who acutely thrombosed an aortobifemoral graft, and one wound infection requiring local care. We have not had to explant any mesh. No symptomatic recurrences were noted in our 11 patients at 1 year. CT follow-up was obtained in all, and two small recurrences were noted radiographically only.6 Pearls and Pitfalls

Careful selection of patients for this extensive surgical repair is essential. Thorough preoperative evaluation and optimization of cardiac, pulmonary, and nutritional status is essential. Counseling of patients on the complexity of the planned operation and expected perioperative course must be complete so that realistic expectations can be maintained. In patients with excessive comorbidities, this operation may be inappropriate

Careful selection of patients for this extensive surgical repair is essential. Thorough preoperative evaluation and optimization of cardiac, pulmonary, and nutritional status is essential. Counseling of patients on the complexity of the planned operation and expected perioperative course must be complete so that realistic expectations can be maintained. In patients with excessive comorbidities, this operation may be inappropriate Knowledge of abdominal wall anatomy and careful attention to planes of dissection are critical to success, allowing for adequate mobilization of the preperitoneal space for wide tension-free mesh reinforcement of the abdominal wall. If you are going to access the lateral abdominal wall via incision of the posterior rectus sheath, great care should be taken to avoid injuring the transversus abdominis muscle and internal oblique, particularly if you are going to add an anterior component separation with external oblique release because this can destabilize the lateral abdominal wall. In most circumstances we find that a posterior release is sufficient and the anterior external oblique release is not necessary.

Knowledge of abdominal wall anatomy and careful attention to planes of dissection are critical to success, allowing for adequate mobilization of the preperitoneal space for wide tension-free mesh reinforcement of the abdominal wall. If you are going to access the lateral abdominal wall via incision of the posterior rectus sheath, great care should be taken to avoid injuring the transversus abdominis muscle and internal oblique, particularly if you are going to add an anterior component separation with external oblique release because this can destabilize the lateral abdominal wall. In most circumstances we find that a posterior release is sufficient and the anterior external oblique release is not necessary. Kinking of the stoma through the layers of the abdominal wall must be avoided. A careful, sequential creation of aligned stoma apertures is important to ensure a straight, nonobstructing path. Reapproximation of the abdominal layers to simulate linea alba at the midline as the stoma apertures are created is essential to create this aligned path.

Kinking of the stoma through the layers of the abdominal wall must be avoided. A careful, sequential creation of aligned stoma apertures is important to ensure a straight, nonobstructing path. Reapproximation of the abdominal layers to simulate linea alba at the midline as the stoma apertures are created is essential to create this aligned path. A biologic mesh is most suited for this repair in order to avoid erosion into the stoma and to avoid infection in these potentially contaminated cases. We have typically used a non–cross-linked porcine dermis mesh, noting its 20 × 20 cm available size, softness, and easy handling. The biologic meshes are expensive, but with the infection and erosion risk, we feel they should be chosen over polypropylene or other synthetic mesh types. The availability of large sizes in these porcine meshes makes them ideal for good overlap of the component separation repair. Importantly, the mesh is placed in a diamond configuration to assist with appropriate, wide underlayment. With our increasing experience with biologic mesh, we have become more comfortable allowing the biologic graft to touch the bowel at the new stoma site. The aperture for allowing the bowel to traverse the abdominal wall is a common point for recurrence. The use of a biologic graft likely reduces the risk of erosion and permits a more physiologic aperture.

A biologic mesh is most suited for this repair in order to avoid erosion into the stoma and to avoid infection in these potentially contaminated cases. We have typically used a non–cross-linked porcine dermis mesh, noting its 20 × 20 cm available size, softness, and easy handling. The biologic meshes are expensive, but with the infection and erosion risk, we feel they should be chosen over polypropylene or other synthetic mesh types. The availability of large sizes in these porcine meshes makes them ideal for good overlap of the component separation repair. Importantly, the mesh is placed in a diamond configuration to assist with appropriate, wide underlayment. With our increasing experience with biologic mesh, we have become more comfortable allowing the biologic graft to touch the bowel at the new stoma site. The aperture for allowing the bowel to traverse the abdominal wall is a common point for recurrence. The use of a biologic graft likely reduces the risk of erosion and permits a more physiologic aperture.Rosen M.J., Reynolds H.L., Champagne B., Delaney C.P. A novel approach for the simultaneous repair of large midline incisional and parastomal hernia with biological mash and retrorectus reconstruction. Am J Surg. 2010 Mar;199(3):416-420.

The Ventral Hernia Working GroupBreuing K., Butler C.E., Ferzoco S., Franz M., Hultman C.S., Kilbridge J.F., Rosen M., Silverman R.P., Vargo D. Incisional ventral hernias: Review of the literature and regarding the grading and technique of repair. Surgery. 2010 Mar 19. [Epub ahead of print]