Open Reduction and Internal Fixation of the Hip

Patricia A. Gray, Mayra Saborio Amiran and Edward Pratt

Hip fractures are the bony injuries that require surgical intervention in the United States most frequently. The annual expense for the treatment of these patients has been estimated as high as $7.3 billion. Because the incidence of osteoporosis in our steadily aging population is increasing, the number of hip fractures is expected to increase from 275,000 per year in the late 1980s to more than 500,000 by the year 2040.1

Surgical Indications and Considerations

Numerous classification systems have been devised to describe hip fractures. However, in the context of surgical exposure, soft tissue injury, and rehabilitation potential, they can be simplified into five main categories:

1 Nondisplaced or minimally displaced femoral neck fractures

2 Displaced femoral neck fractures

3 Stable intertrochanteric fractures

All categories of these fractures can demonstrate good outcomes with surgical intervention and early mobilization.2 This is true regardless of age, gender, or comorbidities. The rare exception is an incomplete or impacted femoral neck fracture in a nonambulatory or extremely ill individual. The expected postoperative stability of the hip is directly proportional to the severity of the injury, the quality or density of the bone to be repaired, and the technical expertise of the surgeon.

The patient’s overall preinjury physical and mental condition is also a predictor of postoperative success. Patients with major cardiopulmonary afflictions, obesity, poor upper body strength, osteoporosis, or dementia in its various forms have increased risk for complications in the treatment of hip fractures. Overall mortality rates of 20% after 1 year, 50% at 3 years, 60% at 6 years, and 77% after 10 years have been reported.3 This is not surprising, because most hip fractures occur in the older adult population.

The traditional goal of rehabilitation has been to restore patients to the level of function that they had before the injury. In many cases this may not be realistic. Only 20% to 35% of patients regain their preinjury level of independence. Some 15% to 40% require institutionalized care for more than 1 year after surgery. Many—50% to 83%—require devices to assist with ambulation.4

Rehabilitation goals must be individualized, with the therapist taking into account all comorbidities, fracture severity, and motivational level of the patient.

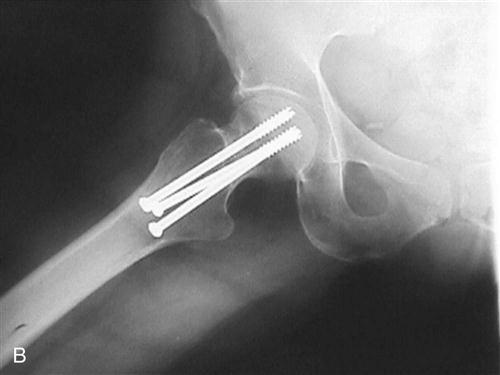

Displaced or minimally displaced femoral neck fractures represent the least severe injuries in the spectrum of hip fractures. They are stable and can bear the full weight of the patient immediately after surgery. Moreover, they require no limitations on range of motion (ROM) or exertion in the immediate postoperative period. The preferred surgical procedure is a fluoroscopically aided placement of cannulated 6.5-mm screws through a limited or percutaneous lateral approach. This approach violates the skin, subcutaneous fat, deep fascia of the fascia lata, and fascia and muscle fibers of the vastus lateralis. Typically blood distends the joint capsule, creating some limitation in hip ROM and pain. No major nerves or vessels are at risk in this approach.

The patient is brought to the operating room, and anesthesia is induced. The patient is positioned supine on a fracture table capable of distracting and manipulating the affected limb. After satisfactory position of the fracture fragments is verified with an image intensifier, surgery is begun.

A 2-cm incision is made along the lateral femur in line with the fractured femoral neck. A guide pin is then placed percutaneously through the lateral musculature at or about the level of the lesser trochanter. The pin is introduced up the femoral neck and across the fracture into the subchondral bone of the femoral head. After two to four guide pins have been placed, the outer cortex is drilled with a cannulated drill and cannulated screws are introduced over the guide pins (Fig. 21-1). The soft tissues are repaired, and a dressing is applied. Femoral neck fractures that occur more toward the base of the femoral neck require fixation that is able to resist the bending movement between the femoral neck and shaft. These are treated much like intertrochanteric fractures, and the operative procedure is described in that section.

Displaced Femoral Neck Fractures

Femoral neck fractures in which the femoral head has been separated widely from the neck do not heal if reduced and fixed by screws or pins. In these fractures the vascular supply to the femoral head (specifically the medial and lateral femoral circumflex arteries) are often severed. In younger patients it is still desirable to attempt fixation despite the high rate of nonunion and osteonecrosis. When open reduction is attempted, the anterolateral exposure of Watson-Jones is preferred because it preserves the blood supply to the femoral head, which enters through the posteroinferior femoral neck.5 This approach is discussed in the section on total hip replacement (THR). Older adult patients are often best treated by bipolar, endoprosthetic, or THR procedures using a posterolateral approach.

The posterolateral approach involves violation of the skin; subcutaneous tissue; fascia lata; gluteus maximus; and short external rotators of the hip, including the piriformis, obturator internus, gemelli, and quadratus femoris. The capsule is incised posteriorly and often released anteriorly. Traction is applied on the gluteus maximus, gluteus medius, and gluteus minimus throughout the procedure. Nerves and vessels at risk include the sciatic nerve, the superior gluteal nerve, the inferior gluteal nerve, and their accompanying vessels. Although the psoas is left alone, it is often inflamed and can scar down and across the anterior hip capsule if adequate postoperative mobilization is not encouraged. Generally incisions are healed by 2 weeks, deep soft tissue healing is well advanced by 6 weeks, and full bony healing is expected at 12 weeks.

The patient is anesthetized and placed in the lateral decubitus position with the injured hip up (see Fig. 15-4); the torso is stabilized, and the hip and affected leg are draped to move freely. The initial incision is centered over the greater trochanter and taken distally 3 inches along the femoral shaft, then proximally and medially 4 inches along the course of the fibers of the gluteus maximus. The deep fascia is incised over the greater trochanter and carried distally along the same line as the skin incision, exposing the origin of the vastus lateralis without violating it. The surgeon digitally palpates the interval between the gluteus maximus and tensor fascia lata proximally, then extends the deep incision in this interval. A large, self-retaining retractor is then positioned to hold the deep fascia apart. The greater trochanteric bursa is incised to expose the short external rotators. The interval between the piriformis, gluteus medius, and gluteus minimus is identified, and the glutei are retracted anteriorly. Carefully the short external rotators are taken off the posterior femoral neck along the posterior hip capsule as a single cuff of tissue for later repair. Alternatively the capsule can be released separately with a T incision. Generally the surgeon must release the piriformis, gemelli, obturator internus, and half of the quadratus to expose the femoral neck to the level of the lesser trochanter. The hip is then flexed and internally rotated to bring the fracture into view. A saw is used to cut the femoral neck smoothly at the proper level, and the femoral head is retrieved from the acetabulum. The acetabulum is examined, and bone fragments are removed along with the ligamentum teres. After exposure is completed, the prosthesis is installed. It is often inserted in 15° to 20° more anteversion than was present with the biologic hip to minimize the risk of dislocation. This occasionally limits external rotation (ER) after surgery but usually not enough to create a functional impairment.

Closure is somewhat more controversial. The author prefers to repair the capsule and short external rotators with a large No. 2 nonabsorbable suture extending through drill holes in the greater trochanter and intertrochanteric line. This limits the formation of heterotopic bone, decreases the incidence of postoperative dislocation, and improves proprioception during rehabilitation. The deep fascia is then repaired, followed by the subcutaneous tissue and skin.

The initial postoperative rehabilitation is predicated on early mobilization to prevent morbidities associated with recumbency, such as deep venous thrombosis, atelectasis, pneumonia, decubiti, and loss of muscle strength and joint mobility. Full weight bearing is encouraged. After arthrotomy each patient must be educated and drilled regarding potentially dangerous hip positions that can lead to dislocation. The risk inherent in the posterolateral approach is greatest with hip flexion greater than 90° and internal rotation (IR), adduction, or both across the midline.

![]() Patients with prosthetic hips should be instructed to follow their hip precautions religiously for the first 6 weeks after surgery, at which time the soft tissue has regained most of its tensile strength. Even then they are at greater risk of dislocation than they were before surgery.

Patients with prosthetic hips should be instructed to follow their hip precautions religiously for the first 6 weeks after surgery, at which time the soft tissue has regained most of its tensile strength. Even then they are at greater risk of dislocation than they were before surgery.

Intertrochanteric Hip Fractures

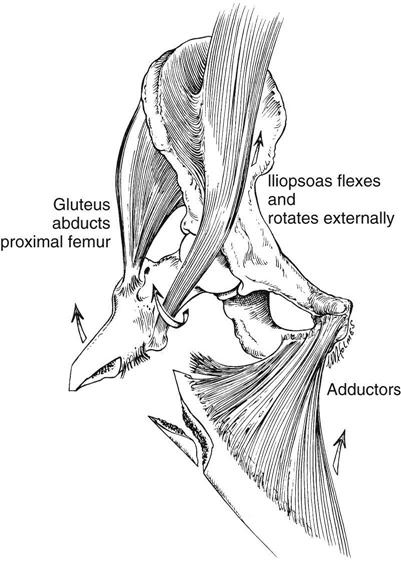

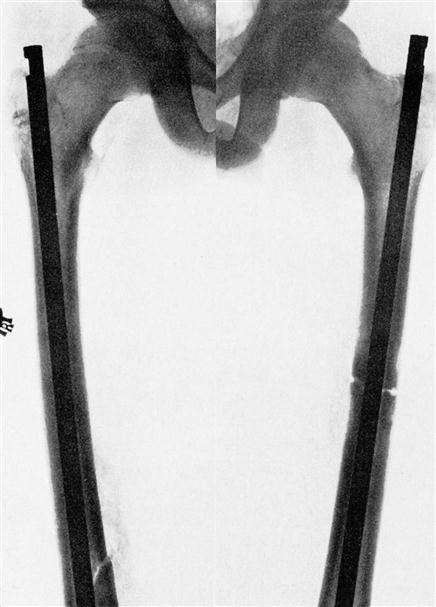

Intertrochanteric hip fractures tend to be the most technically challenging. The intertrochanteric region joins the femoral shaft and neck at an angle of about 130°. ![]() The angular movement created by weight bearing is greatest here, and often weight bearing in the initial postoperative period is not feasible. Morbidity tends to be higher after these fractures, owing to significant comminution of bone and the resultant inadequate stabilization provided by the internal fixation.

The angular movement created by weight bearing is greatest here, and often weight bearing in the initial postoperative period is not feasible. Morbidity tends to be higher after these fractures, owing to significant comminution of bone and the resultant inadequate stabilization provided by the internal fixation.

![]() These patients often must remain at touch down weight bearing (TDWB) or non–weight bearing until fracture healing is demonstrated. The most important prognosticator in this subset of patients is the evaluation of fracture stability (i.e., the tendency of the fracture to collapse or angulate under physiologic loads after surgery). Fractures with an intact posteromedial cortex and those at the base of the femoral neck are stable. These fractures tolerate limited weight bearing in the initial postoperative period without shifting. Surgeons best treat patients with these fractures by placing a sliding compression hip screw device in an anatomically aligned fracture.

These patients often must remain at touch down weight bearing (TDWB) or non–weight bearing until fracture healing is demonstrated. The most important prognosticator in this subset of patients is the evaluation of fracture stability (i.e., the tendency of the fracture to collapse or angulate under physiologic loads after surgery). Fractures with an intact posteromedial cortex and those at the base of the femoral neck are stable. These fractures tolerate limited weight bearing in the initial postoperative period without shifting. Surgeons best treat patients with these fractures by placing a sliding compression hip screw device in an anatomically aligned fracture.

The best surgical approach for the unstable fracture is controversial. Suggested approaches include hip screw devices with or without medial displacement, third-generation intermedullary reconstruction nail fixation, and calcar replacement endoprostheses. The surgical exposure for placement of a calcar replacement prosthesis is as described under the use of endoprostheses for displaced femoral neck fractures. The exposure and morbidity involved in the placement of an intermedullary nail are discussed in the section on subtrochanteric fractures. The exposure for placement of a dynamic compression hip screw is the same regardless of whether a stable or unstable fracture is being addressed. Typically a long lateral approach is used. This approach violates the skin, subcutaneous tissue, fascia lata, vastus lateralis fascia, and muscle belly. Generally in unstable fractures the lesser trochanter and inserting psoas tendon are left free, limiting hip flexion strength in the initial postoperative period.

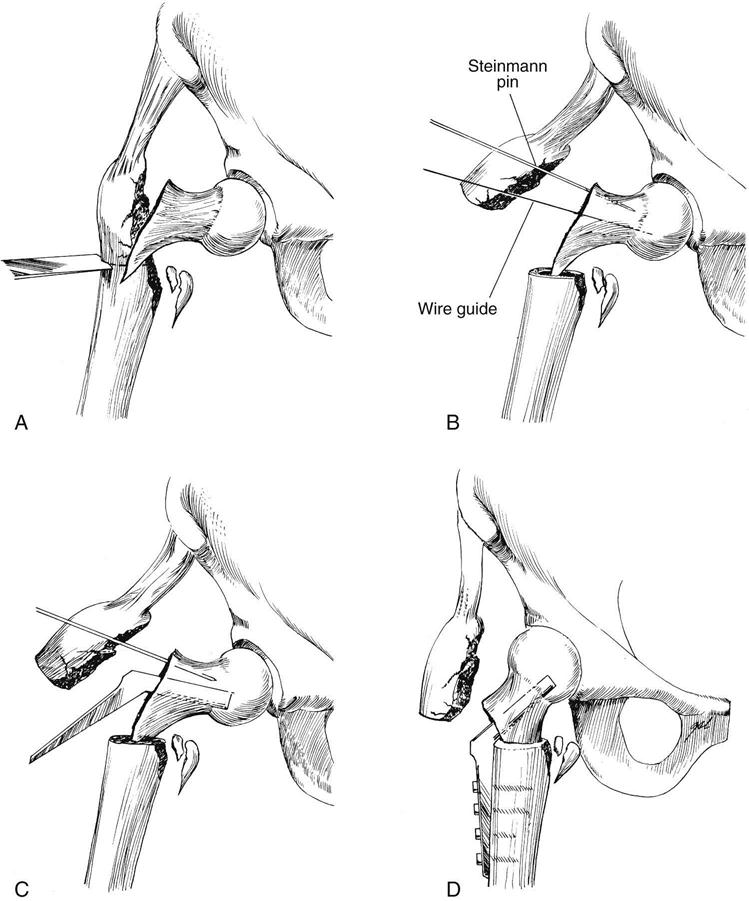

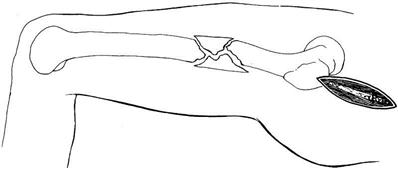

Controversy exists as to whether it is better to align unstable fractures anatomically with a highly angled 145° to 150° compression plate and allow them to collapse into stability under physiologic loads or to perform a “medical displacement” osteotomy to obtain good posteromedial cortical abutment and stability during surgery (Fig. 21-2).

Both methods can lead to stability or instability; therefore each case must be discussed with the surgeon to ascertain the degree of stability obtained and the permitted amount of weight bearing. In addition, both methods shorten the distance between the insertion of the hip abductors in the greater trochanter and the center of rotation of the hip, creating a mechanical disadvantage for the abductors. This can lead to Trendelenburg gait, which must be overcome during the postoperative rehabilitation period.

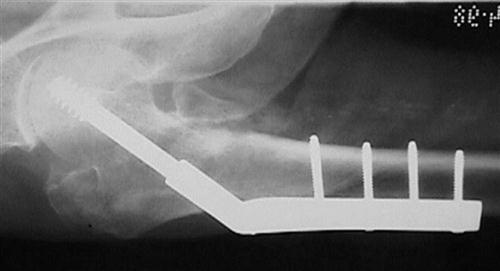

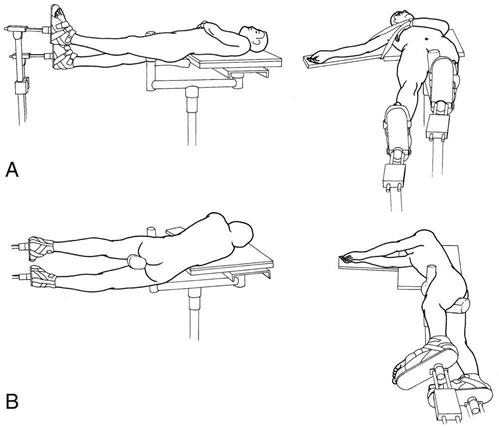

The patient is placed supine on a fracture table with the afflicted limb in the traction boot. Care is taken to place the correct rotation on the distal limb to prevent malalignment. Reduction is carried out under an image intensifier until satisfactory reduction is achieved. Occasionally a satisfactory preoperative reduction is not possible because of posterior sag of the bony fragments, and further reduction must be done manually. After the limb has been prepared and draped, a lateral incision is made from the level of the greater trochanter distally approximately 7 inches, depending on the length of plate to be used. The incision is developed in the same line through skin, subcutaneous fat, and fascia lata. At this point the fascia of the vastus lateralis is followed posteriorly to its origin in the linea aspera. By incising it here the surgeon limits the amount of muscle denervated by the exposure and protects the main muscle mass from damage. The surgeon accesses the lateral cortex of the femoral shaft and places a retractor to maintain anterior retraction of the vastus lateralis, exposing the lateral femoral shaft. After exposure is completed, placement of the fixation device is begun (Fig. 21-3). Closure involves interrupted repair of the fascia of the vastus lateralis, fascia lata, subcutaneous tissue, and skin. The dynamic-compression screw device was not designed to hold the head and neck segment firmly (Fig. 21-4). Rather it allows the ambient muscle forces across the hip joint to pull the fracture fragments together until encountering good bony resistance. In many comminuted osteoporotic fractures, the ability of the screw device to contract is exceeded before good cortical abutment is obtained between the fracture fragments.

![]() In such cases weight bearing must be curtailed until bony healing ensues, or the screw will “cut out” and all stabilization will be lost. Again, the skin is healed by 2 weeks, the deep fascia and soft tissues are healed by 6 weeks, and good bony healing is expected by 12 weeks. In older adult osteoporotic patients with severely comminuted fractures, bony healing can sometimes be delayed for as long as 4 to 6 months. In patients with obviously unstable fractures, weight bearing should be delayed until good bony healing is demonstrated on radiographs. The resultant collapse can often leave a limb significantly shorter. Leg length should be checked after healing and a lift provided if appropriate.

In such cases weight bearing must be curtailed until bony healing ensues, or the screw will “cut out” and all stabilization will be lost. Again, the skin is healed by 2 weeks, the deep fascia and soft tissues are healed by 6 weeks, and good bony healing is expected by 12 weeks. In older adult osteoporotic patients with severely comminuted fractures, bony healing can sometimes be delayed for as long as 4 to 6 months. In patients with obviously unstable fractures, weight bearing should be delayed until good bony healing is demonstrated on radiographs. The resultant collapse can often leave a limb significantly shorter. Leg length should be checked after healing and a lift provided if appropriate.

Subtrochanteric Hip Fractures

The use of advanced intermedullary nailing techniques has revolutionized the treatment of subtrochanteric fractures. Traditionally, these fractures have been difficult to fix because of the extreme angular force centered in this region, as well as the muscular deforming forces and minimal bony interface between the two fragments available for healing (Fig. 21-5).

Moreover, the bone in this region is more cortical in character, with a poorer blood supply and less osteogenic activity than in the intertrochanteric region. The use of a sliding compression screw device has yielded a higher implant failure and nonunion rate than in other regions. The femur can be stabilized with a static locked intermedullary nail without exposing the fracture or disturbing its periosteal blood supply. The two preferred methods of fixation for patients with these fractures are a routine lateral approach for the placement of an extended compression screw device and the placement of a static locked intermedullary nail. The exposure for the lateral compression plate is discussed in the section on intertrochanteric fractures and deviates only in that the exposure must be taken more distally, causing more damage to the fascia lata and the vastus lateralis.

![]() Although this design stabilizes the fracture, weight bearing usually must be delayed, soft tissue exposure is extensive, and healing is often delayed because of destruction of periosteal blood supply around the fracture.

Although this design stabilizes the fracture, weight bearing usually must be delayed, soft tissue exposure is extensive, and healing is often delayed because of destruction of periosteal blood supply around the fracture.

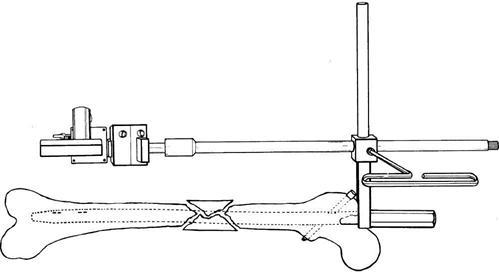

The more limited exposure for a static locked or reconstruction nail runs more proximally through the abductors, with a second stab incision for the interlocking screws at the level of the greater or lesser trochanter and a third stab incision laterally along the supracondylar femur. The newer reconstruction nails run the more proximal interlocking screws from the lateral femoral cortex (at the level of the lesser trochanter), and across and through the prefabricated holes in the nail in the intermedullary canal. The nails then run up the femoral neck, ending in the hard bone of the subarticular femoral head. The distal interlocking screws pass lateral to medial through the lateral cortex of the femur the nail, and finally the medial femoral cortex. This design effectively neutralizes deforming forces across the subtrochanteric femur, allowing full weight bearing from the outset (Fig. 21-6).

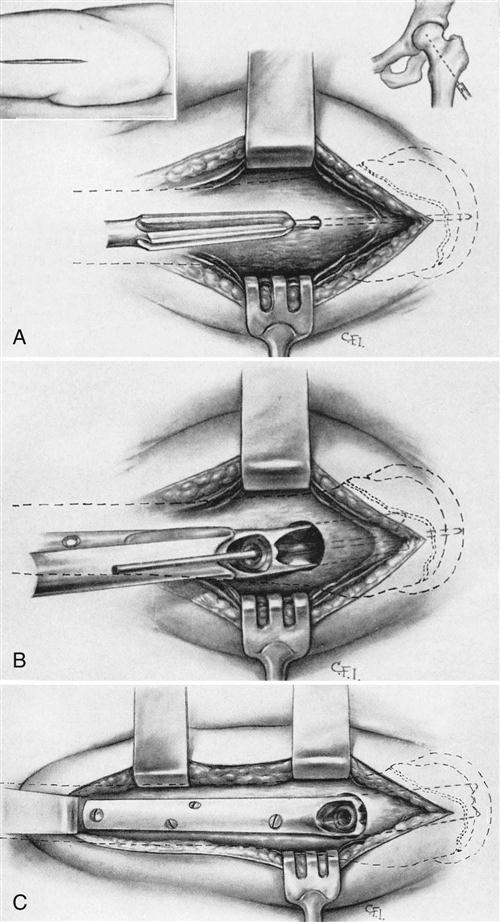

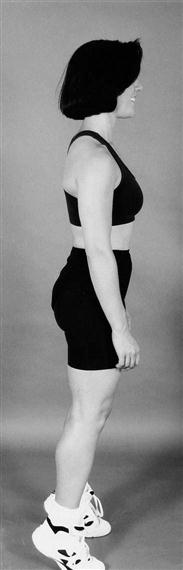

The patient is placed supine on a fracture table with both legs inserted into traction boots. Traction is applied over a perineal post. The legs are positioned with the involved leg adducted across the midline and slightly flexed at the hip. The uninvolved leg is abducted and extended at the hip, lying adjacent to the operative leg (Fig. 21-7). An incision is started 1 inch proximal to the greater trochanter (Fig. 21-8). It is developed proximally and slightly medially 3 inches. The surgeon then extends the incision through the skin and subcutaneous tissue to the fascia of the gluteus medius, which is divided for about 2 inches in line with the skin incision and the fibers of the gluteus medius. Using a small guide pin and fluoroscopy, the surgeon makes a small entry point at the base of the superior posterior femoral area, the piriformis fossa. The guide pin is passed down the femoral shaft approximately 6 inches, and a cannulated reamer is placed over the guide pin to enlarge the entry hole and begin the reaming process. A larger ball-tip guide that is run down across the fracture and down the intermedullary canal to the intercondylar notch replaces the initial guide pin. After this the canal is reamed with flexible reamers in progressively larger sizes until obtaining a good cortical fit. After overreaming a millimeter or two, the surgeon carefully inserts the nail across the fracture under fluoroscopic guidance and then inserts the interlocking screws. The screws at the proximal end of the nail are aimed with the use of a special jig that attaches to the proximal end of the nail (Fig. 21-9). They are inserted percutaneously through the deep fascia and vastus lateralis. The distal screws are usually placed freehand, again percutaneously, using the image to visualize the holes in the nail passing through the iliotibial band and vastus lateralis. Closure consists of repairing the deep fascia, subcutaneous tissue, and skin.

Rehabilitation efforts during the initial postoperative period should consist of regaining control of the proximal hip musculature. Good functional quadriceps contraction and the ability to lift and maneuver the hip against gravity are prerequisites to adequate ambulation. Because of the strength of the fixation, patients can begin full weight bearing immediately after intermedullary reconstruction nailing. Healing normally requires 3 months (Fig. 21-10); nail removal should not be considered before 18 to 24 months.

Therapy Guidelines for Rehabilitation

![]() The course of physical therapy after an open reduction internal fixation (ORIF) procedure at the hip is individualized and depends on the health status of the patient before the fracture, the type of ORIF procedure used, and the precautions ordered by the surgeon. This chapter provides some general guidelines for the rehabilitation process. The physical therapist (PT) must manage the patient’s progress, keeping in mind the patient’s ability to heal and the constraints of the patient’s insurance carrier. The rehabilitation process can be described in three phases: (1) hospital, (2) home care, and (3) outpatient. In many cases, depending on lifestyle demands, the patient may only go through one or two of these phases.

The course of physical therapy after an open reduction internal fixation (ORIF) procedure at the hip is individualized and depends on the health status of the patient before the fracture, the type of ORIF procedure used, and the precautions ordered by the surgeon. This chapter provides some general guidelines for the rehabilitation process. The physical therapist (PT) must manage the patient’s progress, keeping in mind the patient’s ability to heal and the constraints of the patient’s insurance carrier. The rehabilitation process can be described in three phases: (1) hospital, (2) home care, and (3) outpatient. In many cases, depending on lifestyle demands, the patient may only go through one or two of these phases.

Phase I (Hospital Phase)

TIME: 1 to 7 days after surgery

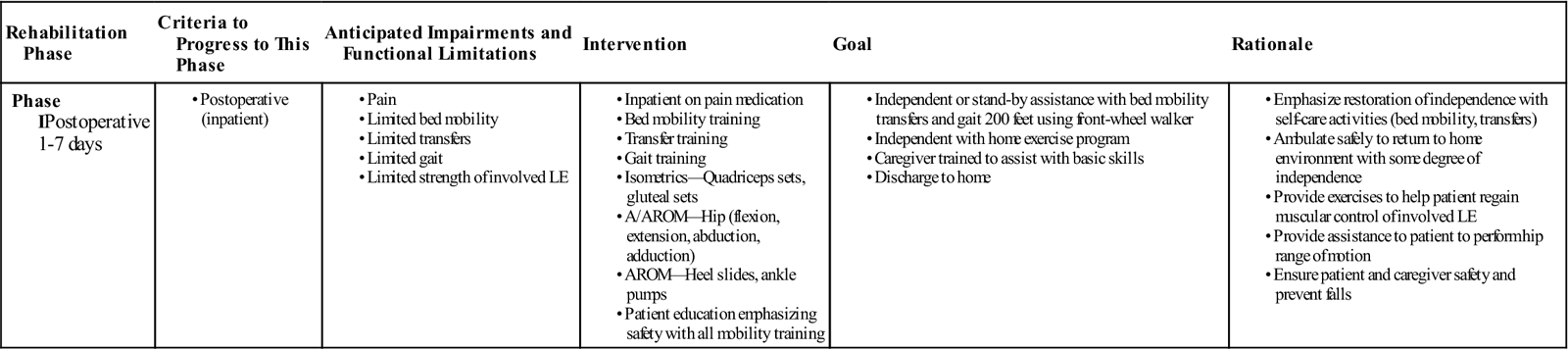

GOALS: To help the patient become independent with transfers and gait using appropriate assistive devices, to ready the patient for discharge from acute care (Table 21-1)

TABLE 21-1

Hip Open Reduction Internal Fixation

< ?comst?>

| Rehabilitation Phase | Criteria to Progress to This Phase | Anticipated Impairments and Functional Limitations | Intervention | Goal | Rationale |

| Phase IPostoperative 1-7 days |

|

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

A/AROM, Active assistive range of motion; AROM, active range of motion; LE, lower extremity.

Treatments performed on the day of surgery, such as incentive spirometry exercises, management of air compression equipment, and donning thromboembolic disease (TED) hose, are generally assigned to the nursing staff. When a good recovery from surgical trauma is demonstrated, hospital-phase physical therapy usually begins on the first day after surgery.

Physical therapy treatment on postoperative day 1 consists of an evaluation, bed mobility, transfer training, gait training, and a beginning exercise program. The patient’s initial goal is to transfer out of bed safely and walk to the bathroom independently using a front-wheel walker (FWW). Some confusion or an emotional reaction to the event that precipitated the surgery may be encountered on the first postoperative day, and the patient may be groggy or in a great deal of pain. Because ORIF is normally an emergency surgery, the patient does not have the advantage of a preoperative training session. However, bed mobility and transfer training may be easier here than with a patient who has undergone THR, because usually no ROM precautions are in place.

Patients who received sacral anesthesia may show a faster initial rate of progress than those who were administered general anesthesia. The patient’s pain medications should be timed to reach peak effectiveness during therapy sessions.

The PT should be informed of the patient’s weight-bearing status, the type of fracture and surgery performed, and any special ROM restrictions. On the first postoperative day, the patient will attempt to walk to a chair and then sit up for approximately 1 hour before returning to bed. This may be repeated two to three times on the first day. The patient will be encouraged to sit up longer each day.

The patient’s skin should be checked daily for pressure sores, especially at the heels. Be sure the patient is placed properly in bed to preclude the tendency to lie in a frog-legged position with the hips in extreme ER and flexion.

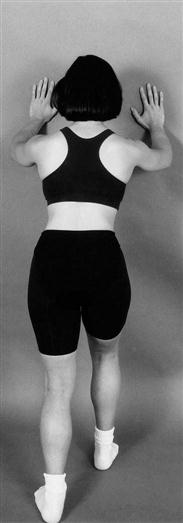

Ankle pumps are the first exercises to be assigned. They help to prevent blood clots and to decrease edema in the legs. The patient should perform at least 10 to 20 repetitions every 30 minutes. Quadriceps sets with and without adductor squeezes (Fig. 21-11), gluteal sets, hamstring sets, and hip abduction sets should be performed three times per day with 10 repetitions of each exercise to begin restoration of proximal hip strength. This program may be expanded to include active assistive and then active hip abduction, adduction, and hip-knee flexion. Encourage the client as much as necessary to complete the program.

Ankle proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation patterns done in both diagonal planes can help prepare the patient for weight bearing. Lower extremity (LE) stretching may be done to avoid contractures and to prepare the patient for a normal gait pattern. The patient can strengthen the upper extremities (UEs) using a Theraband or the hospital bed’s triangle as a pull-up bar. Pelvic tilts and single knee-to-chest stretches of the uninvolved extremity can help decrease lumbar soreness and stiffness.

The patient’s weight-bearing status, assigned by the surgeon, will vary depending on the type of procedure performed. An FWW is recommended for patients with weight-bearing restrictions. However, patients who are assigned non–weight bearing status may feel more secure using a pick-up walker. A platform walker may be appropriate if UE injuries are present. Agile patients are issued axillary crutches immediately regardless of weight-bearing status.

Patients having difficulty with TDWB, defined as less than 10 lb of pressure through the affected leg,6 or with partial weight bearing (PWB), approximately 40% of normal weight bearing on the involved extremity, will benefit from weight shift training on the parallel bars. A very thick-soled shoe worn on the uninvolved leg helps to lift the patient (to facilitate TDWB with the involved leg). With PWB status, stepping onto a bathroom scale helps the patient to determine the appropriate amount of pressure to place on the involved extremity.

Electrical galvanic stimulation is sometimes used to manage edema and electrical stimulation (ES) in the muscle reeducation mode can help facilitate quadriceps (especially the vastus medialis oblique) contraction. ![]() However, electrical modalities tend to be very uncomfortable for most patients, especially those with metal implants. These treatments may be more appropriate at the outpatient stage. The surgeon, as always, should be consulted before the application of these modalities.

However, electrical modalities tend to be very uncomfortable for most patients, especially those with metal implants. These treatments may be more appropriate at the outpatient stage. The surgeon, as always, should be consulted before the application of these modalities.

Transfer to the skilled nursing facility from acute care is expected on the third day after surgery. Patients are discharged from the hospital when they are medically stable and demonstrate independence with bed mobility, transfers, and ambulation (using an appropriate assistive device). Home caregivers should be trained to assist with these tasks safely before the patient leaves the hospital.

Discharge goals are usually attained within 1 or 2 weeks after surgery. Patients may be kept in an extended-care wing longer if no home caregiver is available and assistance is still required for basic mobility. A written exercise program for home use is presented at the time of discharge. The visiting PT in the home will reinforce the skills learned in the hospital.

Phase II (Home Phase)

TIME: 2 to 4 weeks after surgery

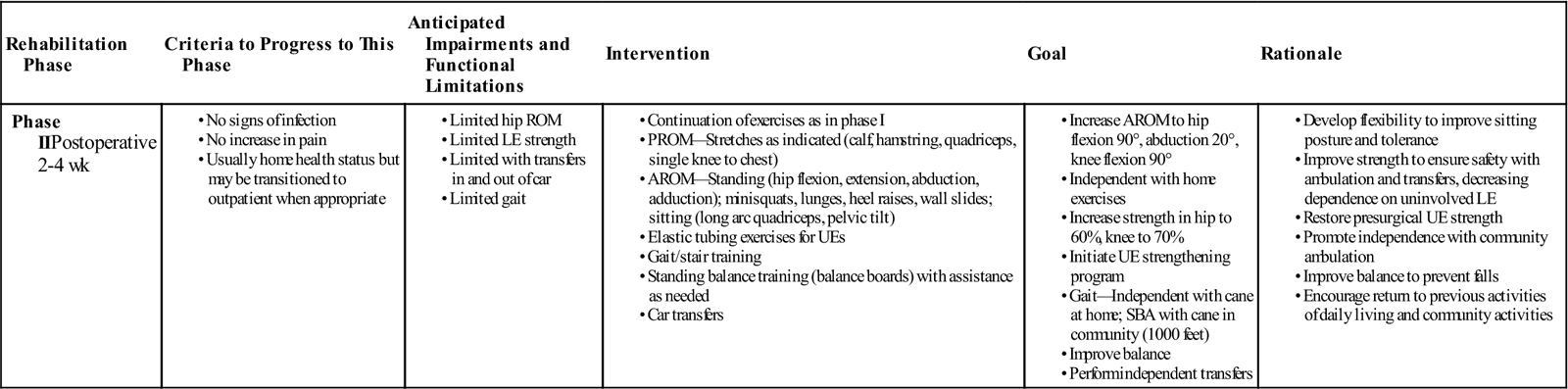

GOALS: To improve hip active range of motion (AROM) to 90°, to educate patient regarding a home maintenance program, to help the patient become independent with transfers and to ambulate at home with appropriate assistive devices, to encourage limited community ambulation (Table 21-2)

TABLE 21-2

Hip Open Reduction Internal Fixation

< ?comst?>

| Rehabilitation Phase | Criteria to Progress to This Phase | Anticipated Impairments and Functional Limitations | Intervention | Goal | Rationale |

| Phase IIPostoperative 2-4 wk |

|

|

|

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

Home care physical therapy is normally authorized for patients who are homebound or would incur undue hardship by leaving home for treatment. Homebound status is a requirement for reimbursement through Medicare and most other insurance plans. PTs usually schedule visits two to three times per week until the patient is no longer homebound or until goals have been met. This is usually achieved within 2 to 4 weeks of the patient’s returning home from the hospital.

Typically the goal of the home care therapist is to ensure the patient’s safety at home and to enable a return to previous community activities with the use of an appropriate walking device. These goals may depend on the patient’s overall health status, motivation level, or previous level of function. In such a case, the patient is discharged when the PT determines that no more progress can be made.

During the initial home care visit, the PT evaluates the patient’s ROM, strength, bed mobility, transfer ability, gait pattern, stair-climbing ability, ability to perform the home exercise program, endurance, pain level, leg length, overall safety awareness, and skin status. The ability of caregivers to assist the patient will also be assessed.

A home care admission assessment will include a review of the patient’s medications. If enoxaparin injections are prescribed to avoid blood clots, be sure that the patient has the appropriate number of syringes and follows through with the injection series.

Equipment needs can include a bedside commode, a raised toilet seat (if the patient has not attained 90° of hip flexion), a shower chair, grab bars installed in the bathroom, railings installed by stairways, and appropriate assistive devices for the progression of gait. Furniture and electrical cords may need to be moved to ensure a clear pathway.

The patient’s understanding of any weight-bearing restrictions and ROM precautions prescribed should be recited and demonstrated. Caregivers should be present during this review.

PTs are now being trained to remove staples because of constraints imposed on nursing visits by insurance carriers. Staples are usually removed at about the fourteenth postoperative day. Proper sanitary technique protocols must be followed. Consult the physician if any irregularity is noted in scar healing.

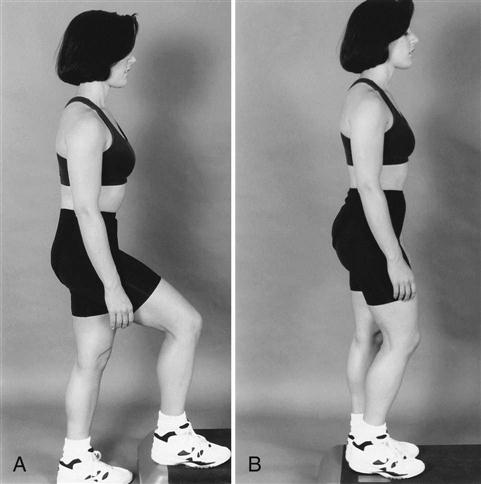

Advance the patient from isometric to active ROM exercises during the home phase. Patients who require an active assist should soon be performing their exercises independently. Bilateral tiptoes (plantarflexion) (Fig. 21-12) and heel cord stretches (Fig. 21-13) while standing can be performed while using a walker or countertop for support. Closed kinetic chain exercises (with the involved leg firmly planted on the ground or on exercise equipment), such as heel raises and minisquats, can also be done at the countertop. Open chain exercises done while standing at this location include hip flexion, hip abduction, and hip extension. Other closed-chain exercises such as modified lunges and wall slides (Fig. 21-14) are added as appropriate.

Hip flexion, extension, and abduction performed while standing are beneficial for the involved leg. They may be alternated bilaterally, depending on the patient’s weight-bearing restrictions. With a status of weight bearing as tolerated (WBAT), the patient may attempt balancing exercises on the involved leg.

The PT should address chronic deficits in flexibility, strength, and balance that may have precipitated the patient’s injury. The postsurgical program should focus on restoring proximal hip strength.

The integrity of the abductors is especially compromised by ORIF surgeries and often the hip abductors were weak before the injury that precipitated the surgery. It may be necessary to stretch chronically flexed hip and trunk muscles before the abductors can be in a position to fire effectively.

Hamstring and calf stretches may be done in the supine or the sitting position using a towel (Fig. 21-15). The quadriceps can be stretched using a towel, with the patient lying prone with knees bent. Pelvic tilt, knee-to-chest, hip rotator stretches, and trunk rotation exercises benefit the low back and the hip.

The patient progresses from using an FWW or two crutches to a cane during this phase. The ability to ambulate safely without an assistive device is sometimes attainable within the time period authorized. Special care should be taken to correct uneven stride length (leading with the involved extremity and stepping-to with the uninvolved extremity), knee flexion in the late stance phase, forward flexion at the waist, and overstriding with crutches.6 Trendelenburg signs in gait following an ORIF are common because of disruption of the abductors. Be sure to cue and facilitate the engagement of the abductors in both exercises and gait.

Gait training includes stair climbing. Initially the patient should walk up the stairs leading with the strong leg and descend the stairs leading with the operative leg in a step-to pattern.

Training to step up and down safely from curbs, to walk on uneven surfaces, and to transfer in and out of cars also is provided in the home phase.

A balance retraining program may benefit patients who have vestibular or neurologic involvement. Vision problems should be referred to the physician.

Home health physical therapy is usually finished within 2 to 4 weeks. The patient should have 90° of hip flexion and 20° of hip abduction at this point. The quadriceps and hip abductor strength should be fair to fair plus (3/5 to 3+/5 with a manual muscle test), and the patient should be able to perform all exercises actively.

The majority of ORIF patients are older people with fairly sedentary lifestyles. They may refuse further rehabilitation past the home care phase. Walking programs should be strongly encouraged with these patients. Swimming and bicycle riding are recommended, when realistic, for long-term exercise programs; tai chi has been shown to decrease the risk of falls in older adults.7 Active patients with more rigorous lifestyle requirements should go on to outpatient therapy for further strengthening.

With osteoporosis so prevalent in this population, the patient may be advised to consult the primary care physician regarding the propriety of a calcium replacement program or hormone replacement therapy.

Phase III (Outpatient Phase)

TIME: 5 to 8 weeks after surgery

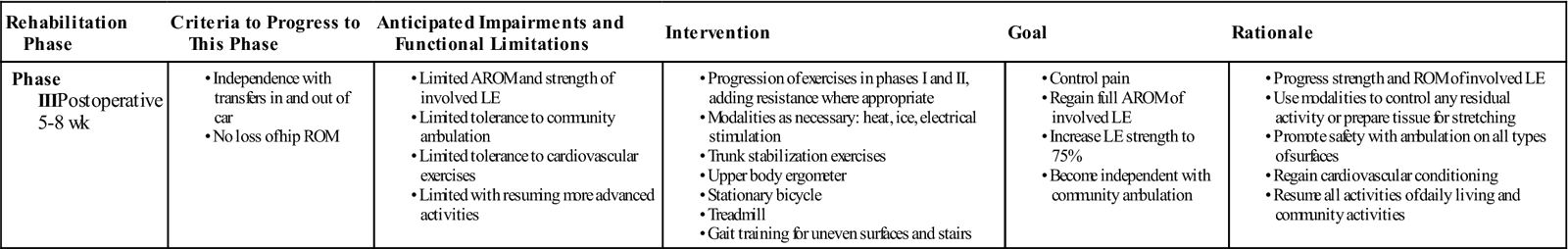

GOALS: To encourage patient self-management of exercises, to help the patient become independent in community ambulation, to increase the strength of the LEs (Table 21-3)

TABLE 21-3

Hip Open Reduction Internal Fixation

< ?comst?>

| Rehabilitation Phase | Criteria to Progress to This Phase | Anticipated Impairments and Functional Limitations | Intervention | Goal | Rationale |

| Phase IIIPostoperative 5-8 wk |

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

AROM, Active range of motion; LE, lower extremity;

ROM, range of motion.

Outpatient physical therapy is intended to increase the involved extremity’s flexibility toward full ROM and increase its strength to at least the good minus level (4-/5 manual muscle test). Gait pattern irregularities are to be normalized. Cardiovascular capacity also may be improved. These treatments should be conducted two to three times per week if the patient’s insurance policy permits. The duration of outpatient rehabilitation depends on the patient’s ability to make objective progress and on whether the intervention or treatment requires the skill of a PT.

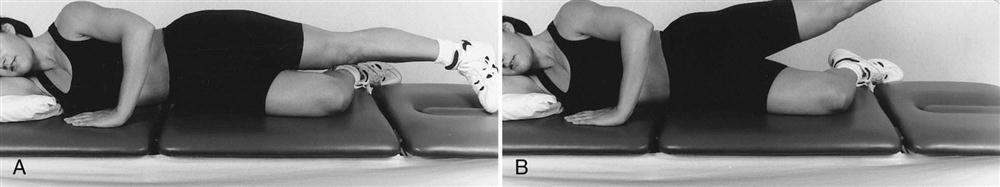

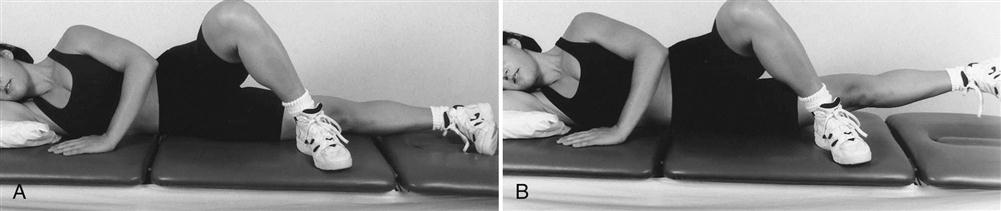

All exercises should be done actively by this time. Exercises previously performed in gravity-eliminated positions, such as supine hip abduction (Fig. 21-16) and adduction (Fig. 21-17), are progressed to side-lying gravity-resisted positions. Ankle weights can be added if appropriate.

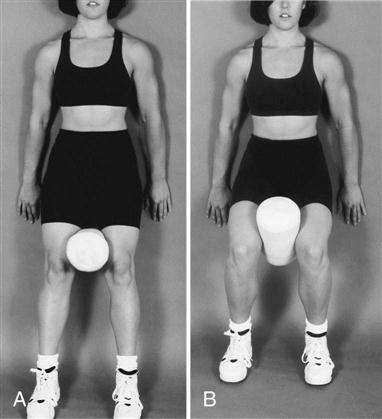

The closed-chain exercises mentioned previously also are performed in the outpatient clinic. Minisquats and wall slides can emphasize a vastus medialis oblique contraction with the addition of an isometric hip adductor squeeze using a pillow or small ball. Lunges with the involved leg on a small step can progress to stair climbing on larger, more normal-sized steps. If the patient is still doing stairs in a step-to pattern, progress him or her to a step-over-step pattern if possible. Standing balance exercises on the affected leg are appropriate with WBAT status.

Cardiovascular exercise is important during this phase to increase circulation throughout the body and endurance for ambulation. An upper body ergometer or a stationary bicycle can be introduced at this phase. The patient’s tolerance for these activities could be built up to a combined 15 to 30 minutes, if possible.

The modalities mentioned in the hospital phase may be performed here with the approval of the surgeon. Balance retraining programs may be expanded to include various balance boards. Spine stabilization exercises can include those done in the prone and quadruped positions. Core strengthening should be included, as well as Pilates exercises when realistic.

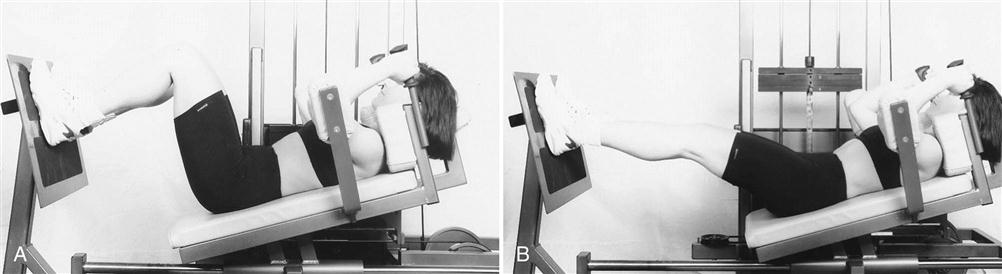

Inclusion of the leg press (Fig. 21-18) and other weight-training equipment may be appropriate in the clinic phase. At the PT’s discretion, a treadmill also may be used to contribute to balance and gait retraining. The therapist should consider activities that the patient can carry on in life when the rehabilitation phase is over.

Troubleshooting

Complications may arise in the course of rehabilitation. Examples that should be referred to the surgeon include the following:

Other problems that may arise are the responsibility of the surgeon, but the PT can use palliative measures to assist the patient. Leg length discrepancy is an example. The patient can continue gait training with a temporary shoe insert or with shoes of different heel heights. The surgeon may later prescribe a permanent orthotic. Persistent edema is treated with medication. Patients should be advised to elevate their legs, rest more often, wear TED hose, pump their ankles, use kinesio tape, and apply ice to swollen areas.

Pain exacerbations are usually treated with medication. Possible side effects of the medication include nausea, constipation, and hypertension. The therapist can assist in pain reduction with modalities, exercise, ice, and positioning.

Clinical Case Review

1Why do ORIF patients differ emotionally from other postsurgical orthopedic patients?

They cannot prepare for their surgery because it is an emergency surgery. Some have sustained their injury in an accident where other loved ones have been injured. Their situation needs to be appreciated and respected. The mortality rate following a hip fracture is high and elderly patients are aware of this. They may be worried that they will not recover or may not be able to return to their homes. Expect to give these patients a lot of encouragement.

2How can the treadmill be useful at the outpatient phase?

At slow speeds, the hip abductors, core trunk muscles, and glutes are forced to engage during the stance phase on the unstable surface of a treadmill. Placement of a mirror in front of the treadmill can help the patient to observe and correct gait pattern irregularities. The treadmill may be a beneficial activity following discharge from the outpatient clinic.

3Upon the PT’s arrival at the patient’s home, the patient’s operative limb is found to be ruborous, warm, severely swollen, and very painful despite elevation and the use of ice. What needs to be done?

Be sure that the patient was discharged with the appropriate number of enoxaparin syringes and has followed through with these injections as prescribed. The patient may have a clot in his leg. Check the status of the surgical scar. There is the possibility of an infection. Make sure that the patient has taken any antibiotics prescribed since other causes of infection may be due to dental work or other medical procedures unrelated to the THR. Refer the patient back to the surgeon for further evaluation.

4Why do so many patients have difficulty performing hip abduction exercises?

Frequently patients will substitute hip flexion for true abduction. They have difficulty firing the glute medius and glute minimus because of their chronically flexed posture. Good hip extension is needed for true abduction to occur and good concentric and eccentric control of the hip rotators are needed for a normal gait pattern. Lunges, done standing in a doorway with elevated arms on either side of the door frame, can effectively stretch the plantar flexors, hip flexors, arms, and trunk while strengthening the opposite LE quads. Stronger, more mobile patients may be able to assume a prone position to stretch chronically shortened hip and trunk flexors. Sidestepping is a functional abduction exercise that challenges balance and stimulates both sets of glutes and engages eccentric hip rotators in stance phase. Backstepping can challenge even more aspects of balance and posture.

5Mary, 73 years old, had an R hip ORIF and has a chronically flexed trunk and hips. What should the therapist consider in designing a rehab program for Mary?

A postural assessment should be done and the contractures noted should be addressed through a cautious stretching program. Careful straight leg hamstring stretches done with the therapist’s assistance may be added to the supine exercise series. The Achilles tendon stretch can be done at a kitchen countertop, walker, or at the wall. The patient can stand in a doorway and perform a lunge while her UEs are placed on either side of the doorframe to stretch a chronically tight trunk, shoulder, and hip flexors.

6What should a PT consider when performing a home safety evaluation for a patient who has sustained a fracture from a fall?

Are steps, floorboards, and tiles secure?

Are rugs, especially carpet on stairs, secure?

Which scatter rugs should be removed?

Are railings and banisters secure?

Which electrical cords should be taped down or removed?

Are stairways, hallways, and entryways clear of obstacles?

Are pets and small children under control when near the patient?

Are grab bars available in the bathroom?

Are there nonskid mats in the shower/tub?

Is durable medical equipment adjusted to proper height? Should home furniture be raised?

Is lighting adequate? Are night lights available?

Is the patient wearing nonslippery shoes or slippers?

Are emergency numbers posted near the telephone?

Is an occupational therapy evaluation needed for home adjustment?

Should the patient have an emergency call system installed?

Are caregivers well trained to assist?

Are the eyeglasses that the patient is wearing clean? Many patients who think that they have lost most of their vision are trying to see through filthy eyeglasses.

7During gait training Julie has difficulty maintaining TDWB on the affected LE. She tends to place approximately 20% of her weight onto her affected leg. She attempts to respond to verbal cues but is unsuccessful. A scale was placed under the affected leg so that Julie could see and feel how much weight she was transferring onto her leg. Although she improved after using the scale, she still could not maintain a safe level of TDWB through the affected leg. What is another way to assist her in maintaining TDWB status?

A very thick-soled shoe worn on the uninvolved foot helps lift the patient and facilitates TDWB status. Also a saltine cracker packet taped to the bottom of the operative foot can give the necessary feedback during stance phase. When the patient progresses to PWB, use the bathroom scale again to help the patient determine how much weight to put on the operative LE.

8Ruth is 70 years old. She sustained a hip fracture at home when she tripped and fell. She had an ORIF on her left hip 3 months ago. Before her fall, she could walk without an assistive device. Presently she walks at home without an assistive device but needs a cane to ambulate around the community. She rarely goes out because she is so fearful of falling. She has maintained a strengthening home exercise program. Ruth feels that her leg remains weak despite all her exercising. Her LE flexibility is generally restricted throughout. The left leg is more restricted than the right. Ruth’s balance and coordination also are impaired. Movements other than forward gait appear labored and slow. Left hip strength is generally 4-/5. Should strengthening, stretching, ROM, balance training, or coordination training be emphasized initially during treatment?

The therapist ascertained the conditions that were hampering progress with strength, balance, and ease of movement during gait. LE flexibility exercises with the guidance and careful assistance of the therapist were emphasized during the first four visits. Balance, coordination, gait, and strength issues also were addressed. As the flexibility of the LEs increased, advances with strength could be obtained more easily. In addition, the patient was able to move her LEs more freely during lateral or backward movements. Therefore balance and coordination also progressed. Ruth’s confidence grew, and in a few weeks she was safely walking and maneuvering around the community without an assistive device.

9Robert is having difficulty with transferring into and out of his car safely. What adjustments can help him?

A clean plastic trash bag placed over the passenger’s seat provides a slippery surface, which allows the patient to glide-pivot around on the passenger’s seat and assume the rider’s position more easily. If the height of the seat is adjustable, then raise the seat to the highest possible position. The back of the passenger seat may need to be tilted backward if a precaution of less than 90° flexion at the hip is in place.

10What activities are recommended following discharge from outpatient physical therapy?

By the end of the outpatient phase, the patient should have a well-rounded program that can be continued at home or at a fitness center. Bicycling, recreational walking, tai chi, and swimming are excellent long-term options for the active patient recovering from hip ORIF surgery. Wii Fit or Wii Sport, now being featured at nursing homes and senior center exercise programs, are recommended for home use to improve balance, strength, and endurance.

11How can a patient build enough hip strength to allow normal stair climbing?

The patient with WBAT status can practice step-ups onto a book or a step with a very narrow rise using the operative leg (Fig. 21-19). An initial isometric contraction can precede the step-up onto progressively taller rises until the patient is able to walk up and down stairs in a normal step-over-step pattern while holding a railing.

12How can problems because of abductor weakness manifest in the hip ORIF patient?

Surgical disruption of the abductor tendons can cause traction neurapraxia on the superior gluteal nerve. A shortened abductor lever arm can cause a Trendelenburg sign to appear with gait. With abductor weakness, secondary joint pain can develop at the spine, knees, and opposite hip because of the added stresses of the shifting of the center of gravity while ambulating.