Open Reduction and Internal Fixation of the Ankle

Graham Linck, Danny Arora, Robert Donatelli, Will Hall, Brian E. Prell and Richard D. Ferkel

Introduction

The treatment of ankle fractures dates back to antiquity. Evidence of healed ankle fractures has been noted in the remains of mummies from ancient Egypt.1 Hippocrates recommended that closed fractures be reduced by traction of the foot, but few other advances in the understanding and treatment of ankle fractures were made until the middle of the eighteenth century.2–4 Operative treatment of ankle fractures was popularized by Lambotte5 and Danis6; the AO group began a systematic study of fracture treatment in 1958.7–9 Since these original investigators, significant progress has been made in the treatment of ankle fractures.

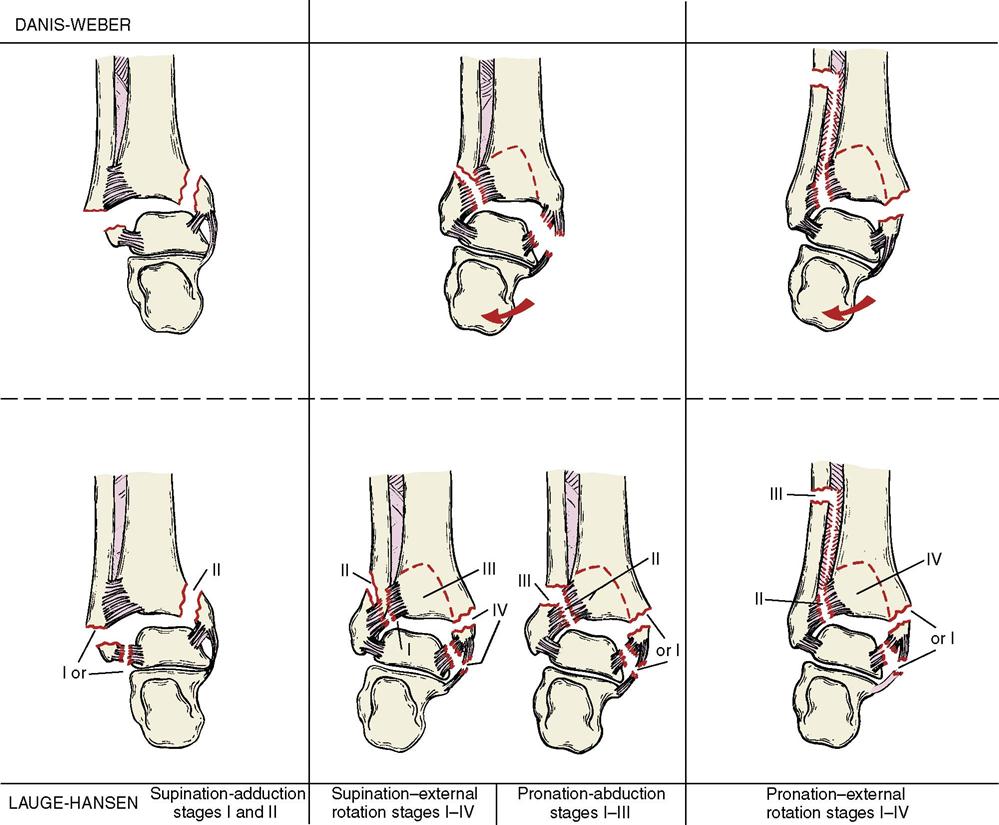

Much of the current understanding of the mechanism of ankle fractures has developed from the work of Lauge-Hansen.4 In his system, the position of the foot (pronation or supination) at the time of the injury is described first and the direction of the deforming force is described second. Ankle fractures currently are classified most commonly by two systems: Lauge-Hansen4 and Danis-Weber10,11 (Fig. 29-1). The latter system is based on the location of the fracture of the fibula: infrasyndesmotic, transsyndesmotic, and suprasyndesmotic. Fractures also are classified by the number of bones that are affected—that is, a bimalleolar fracture involves injury to both medial and lateral malleoli, whereas a trimalleolar fracture indicates that the medial, lateral, and posterior malleoli have all been fractured.

An ankle fracture is a debilitating injury, especially if the fracture is unstable. The treatment of choice for an unstable ankle fracture is open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF). Surgical treatment of a displaced, unstable ankle fracture centers on anatomic restoration of the bony and ligamentous structures that surround the joint. As technology and surgical techniques have advanced, so have the outcomes for ORIF.12–14

Surgical Indications and Considerations

Ankle fractures can be treated conservatively if the ankle mortise remains stable. The medial clear space (space between medial malleolus and talus) or lateral clear space (space between lateral malleolus and talus) must measure less than 3 mm on a mortise radiographic view, or less than 5 mm on a stress radiographic view. It is important to ensure that the talus is well reduced beneath the tibia plafond and not subluxated forward or backward. The following specific injuries are indications for conservative treatment: isolated nondisplaced medial malleolar fracture or tip avulsion fracture, isolated lateral malleolar fracture with less than 3 mm displacement and no talar shift, and a posterior malleolar fracture with less than 25% joint involvement or less than 2-mm stepoff. Conservative management usually entails immobilization in a short-leg cast or boot, which extends to the tips of the toes with the foot in an appropriate position for the type of fracture deformity. Any fracture of the ankle with a residual talar tilt or subluxation, in which the ankle mortise is not anatomically reduced, warrants surgical fixation.

In general, ORIF should be performed on all patients, regardless of age, gender, activity level, or vocation, as long as they are healthy enough to undergo the procedure. However, exceptions do exist, including paraplegics and quadriplegics, and patients who are nonambulatory and lack sensation to the lower extremities.

Preoperative variables that predict a successful outcome include an otherwise healthy patient who is well motivated to recover after surgery. Systemic diseases such as osteoporosis, diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, alcoholism, and tobacco abuse can all affect the ultimate outcome of surgery. These variables affect wound healing, as well as the healing of the fracture itself.

Surgical Procedures

Patient Evaluation

It is important to get a history on the mechanism of injury, and if possible, the position of the ankle, as well as the direction of force. This will not always be possible, because most patients will only be able to describe a twisting or rolling type of injury. Completing your history with current medical comorbidities and social habits is necessary for patient outcomes. Physical examination includes inspection, palpation, and neurovascular examination. It is crucial to note any gross deformity, which may indicate possible dislocation, and would necessitate early closed reduction and splinting, as well as any wounds around the ankle, which may indicate an open fracture, and would require emergent surgical irrigation and débridement.

A careful preoperative assessment of not only the patient’s health, but also the fracture and the patient’s swelling and skin tension, is important to a successful outcome. In some cases surgery may have to be delayed for as long as 14 days to allow swelling to resolve so the skin can be closed at the end of surgery without a wound slough. Recently, a foot and ankle pump device has been used to reduce swelling rapidly to permit earlier surgery and fewer complications.

Initially, patients may be too swollen to wear a cast. In this instance a bulky dressing with cast padding and bias type of compression wrap is applied with a posterior splint. The patient remains non–weight bearing with crutches and elevates the injured ankle above the heart to promote reduction of swelling.

Surgical Technique

The currently accepted method for fracture ORIF is the AO (Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen, or Association for the Study of Internal Fixation) technique developed in Switzerland. This technique emphasizes the use of plates, screws, and wires as needed to achieve rigid fixation.

Four criteria must be fulfilled to achieve the best possible functional results in the treatment of ankle fractures:

1 Dislocations and fractures should be reduced as soon as possible.

2 All joint surfaces must be precisely reconstituted.

3 Reduction of the fracture must be maintained during the period of healing.

4 Motion of the joint should be instituted as early as possible.

Anesthesia and Positioning

The patient is taken to the operating room and a popliteal block is done to help control postoperative pain. General or epidural anesthesia is administered. Prophylactic antibiotics are given, and a fluoroscopy table is used.

The patient is usually placed supine with a bump under the ipsilateral hip to ease the access to the lateral ankle. A pneumatic tourniquet can be applied to the proximal ipsilateral thigh and used if required. The affected limb is prepped and draped in a sterile fashion. The prone position may be used in rare instances where a posterolateral approach would be required to allow access to the posterior malleolus.

Procedure

Recent research at the Southern California Orthopedic Institute indicates that a high percentage of patients have intraarticular pathology associated with ankle fractures.13 Almost 75% of patients with displaced ankle fractures have an osteochondral lesion of the talus that is not evident on preoperative x-ray films and can only be seen on arthroscopy before ORIF. On the basis of these results and Lantz’s research8 (which found a 49% incidence of injuries to the talar dome articular cartilage in isolated malleolar fractures), the authors recommend arthroscopy before ORIF of all ankle fractures. This approach is also supported by Hintermann’s study15 that showed a 79% incidence of osteochondral lesions of the talus with an ankle fracture.

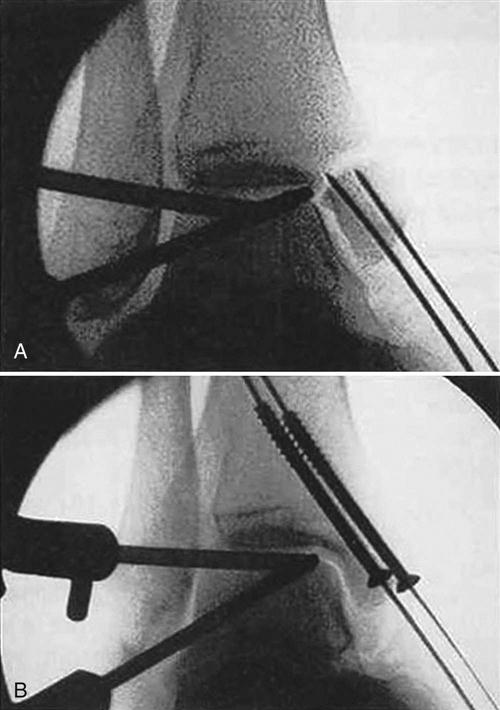

The arthroscopic evaluation is done as described in Chapter 30. All intraarticular pathology is documented and appropriately treated. The surgeon must examine carefully for osteochondral lesions of the talus, tears of the deltoid, anterior talofibular and syndesmotic ligaments, and dislocations of the posterior tibial tendon, which may impede fracture reduction. Some fractures can be reduced and internally fixated by arthroscopic means alone.16 A typical example is a patient with a fracture of the medial malleolus that was débrided arthroscopically and fixated percutaneously with two cannulated screws (Fig. 29-2). We have also had good long-term results treating Tillaux fractures in an arthroscopic manner. After the arthroscopic portion of the procedure is completed, if the fracture is not amenable to all-arthroscopic reduction, the ankle is prepared and draped again, gloves are changed, and new sterile instruments are used.

Incisions are made over the lateral, medial, or posterior malleolus, depending on the nature of the fractures. When a fracture apparently involves only the medial malleolus, the surgeon should search for an injury to the syndesmosis with subsequent tearing of the interosseous membrane, which may result in a high fibular fracture. This type of fracture, which also is known as a Maisonneuve type of fracture, could even occur at the fibular head and may be missed if the surgeon is not diligent. In this instance, the medial malleolar fracture is reduced anatomically, usually with two screws inserted proximally through a small incision from the tip of the medial malleolus. The deltoid ligament is split in line with its fibers, and the two screws are inserted parallel to each other under fluoroscopic control. If the syndesmosis and interosseous membrane have been torn and are unstable, one or two syndesmotic screw(s) are inserted through the fibula and tibia, exiting the medial border of the tibia with the foot in dorsiflexion. The screw(s) are not placed with compression because compressing the syndesmosis restricts motion postoperatively.

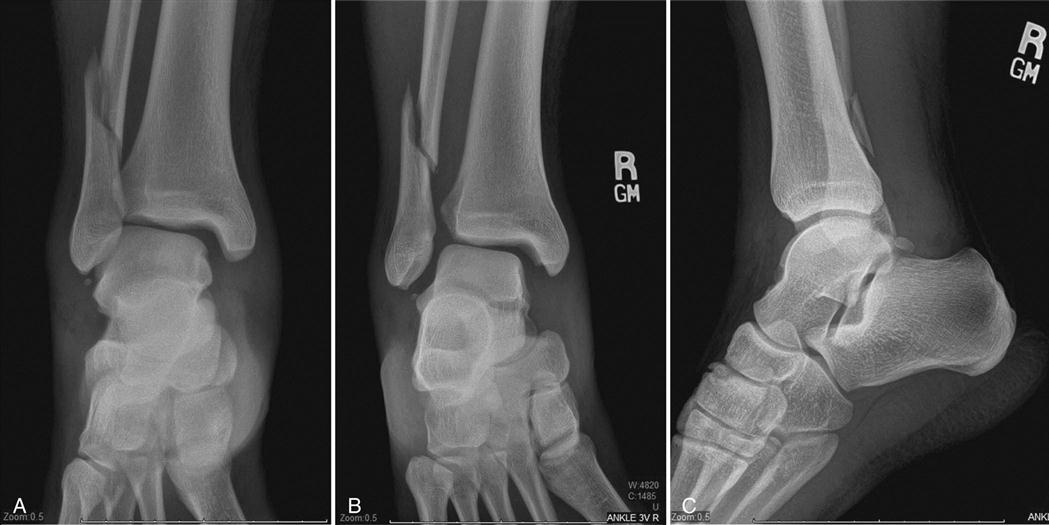

When a Weber B fracture occurs with disruption of the deltoid, syndesmosis, and interosseous membrane, anatomic reduction of the medial and lateral clear spaces is critical (Fig. 29-3). After arthroscopically débriding the ankle and cleaning out the torn ligaments, ORIF is performed.

The surgeon makes an incision over the fracture site and extends it proximally and distally on the fibula. Dissection is carried down to the periosteum and the fracture site. Care is taken to identify the superficial peroneal nerve, which crosses the field approximately 7 cm proximal to the distal tip of the fibula. The fracture is exposed and the periosteum is elevated with sharp dissection (Fig. 29-4). The surgeon uses a curette to remove the hematoma and applies reduction clamps to assist in reducing the fracture. Reduction of the fracture usually also requires traction and rotation of the foot and ankle (Fig. 29-5). When anatomic reduction has been achieved, frequently one or two lag screws are used to provide interfragmentary compression across the fracture site. After this is accomplished, an appropriately sized plate is centered over the fracture site and stabilized with screws.

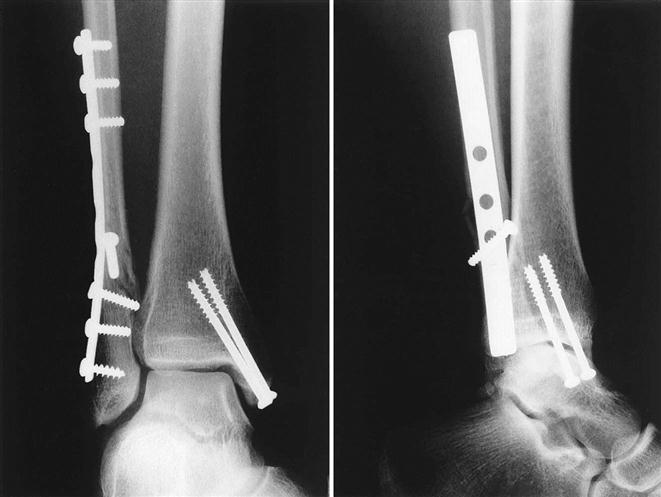

One or two syndesmosis screws or a screw and tightrope are then inserted to reduce the ankle, and the reduction is checked under fluoroscopy (Fig. 29-6). Postoperative radiographs are taken to verify anatomic reduction of the fractures and syndesmosis, and appropriate positioning of the screws and plate (Fig. 29-7).

When both the medial and lateral malleoli have been fractured, the lateral malleolus is approached first (Fig. 29-8). An incision is then made over the medial malleolus as previously described, the fracture site is exposed, the hematoma is removed, and the fracture is reduced. The surgeon inserts one or two screws. Postoperative x-ray films demonstrate anatomic reduction of the fractures with good position of the plate and screws (Fig. 29-9).

In ORIF of a trimalleolar fracture, the lateral and medial malleoli are addressed as previously mentioned. Using the fluoroscope, the surgeon then reduces the posterior malleolar fracture by manipulating the fragment into place and making a small incision along the anterolateral aspect of the distal tibia. Two guide pins are inserted to reduce the fragment and one or two cannulated screws are inserted from anterior to posterior to hold the posterior malleolar fragment in place. In general, posterior malleolar fracture fragments do not require internal fixation if they involve less than 25% of the articular surface. If the posterior malleolus needs to be addressed directly, a posterolateral approach can be used.

Postoperative Plan

After surgery the patient is splinted in a well-padded short-leg cast in the neutral position; the cast is split in the recovery room to allow for swelling. Patients are asked to keep the limb elevated as much as possible for the first postoperative week. The procedure can be done on an outpatient basis if the pain level is not too severe, but in some instances the patient may be required to stay 1 or 2 days in the hospital. After discharge the patient is non–weight bearing on crutches for at least 4 weeks. The cast is changed at 1 week after surgery, the wound is inspected, and all new dressings are applied. At 2 weeks after surgery, the stitches are removed and a new short-leg cast is applied for 2 additional weeks. At 4 weeks after surgery, another short-leg cast is applied and the patient starts partial weight bearing, gradually increasing to full weight bearing without crutches. After the fracture has healed, the patient can wear a supportive brace and start pool and then land physical therapy. In patients with stable, reliable fixation, early motion can sometimes be initiated after the third or fourth postoperative week to facilitate early return of motion and strength.17 Patients are restricted from operating an automobile for 9 weeks following right-sided ankle fractures.

If a syndesmosis screw or screws were inserted during fixation, the patient must be non–weight bearing for 6 to 8 weeks. The screw(s) is removed at 12 to 16 weeks postoperatively, since it can break with weight bearing if left in place. Physical therapy is started 6 to 8 weeks after surgery. After the screw(s) is removed, the patient can be more aggressive with physical therapy and weight-bearing activities.

Surgical Outcomes

A successful outcome is defined as a fully healed fracture, with the patient achieving near full or complete range of motion (ROM) with normal strength and function.9 Function is defined differently for each patient—an athlete’s function is different from that of a sedentary, elderly patient. Several different grading systems, including subjective, objective, and functional data, are used to evaluate ankle fracture results. However, ankle fracture results are difficult to compare because of the multitude of fracture patterns and different circumstances of treatment. Results can be affected by many things, including severity and type of injury, associated intraarticular problems, preexisting arthritis,3 age and reliability of the patient, quality of the bone, and other site injuries. Finally, it should be noted that there is a potential for superficial nerve injury after surgical repair, as well as syndesmosis instability.18

Younger age, male sex, absence of diabetes, and a lower American Society of Anesthesia class are predictive of a good functional recovery at 1 year following ankle fracture surgery.11 Anand and Klenarman19 report that, in a sample of 80 patients older than 60 years, 88.5% were satisfied with their postoperative outcome. Ankle fractures are the fourth most common fracture in those older than 65 years and usually are the result of significant trauma.12 Recent studies have not demonstrated any age-related risks to surgery beyond those posed by other comorbidities.14,20 Therefore, the criteria for surgery should not be different for elderly patients than for younger individuals.

Postoperative Considerations

In patients with stable, reliable fixation, sometimes early motion can be initiated after the third or fourth postoperative week to facilitate early return of motion and strength.17 Early motion and exercise have been found to have beneficial effects following ankle ORIF. Patients have demonstrated decreased activity/functional restrictions, decreased pain, and improved ankle range of motion with early mobility. However, a higher rate of adverse events following ankle ORIF was associated with early exercise/mobility so care must be taken by both the therapist and patient to not overstress healing tissues.21

When a syndesmosis screw has been inserted, the patient must be non–weight bearing for 6 to 8 weeks; the screw is removed at 10 to 12 weeks postoperatively. The screw will break with weight bearing if it is left in place. Physical therapy is started 6 to 8 weeks after surgery. After the screw is removed, the patient can be full weight bearing and initiate physical therapy.

Complications

Minor complications include incidence of 4% to 5% wound problems (epidermolysis and superficial infection) and peroneal tendinitis with painful hardware. Major problems include nonunion, hardware failure, 1% to 2% deep infections (up to 20% in diabetic patients with peripheral neuropathy), posttraumatic arthritis, and compartment syndrome. Patients who have any condition (i.e., diabetes, peripheral artery disease) that might compromise circulation in the distal extremities are at an increased risk for complications relating to wound healing and closure.22

Therapy Guidelines for Rehabilitation

The physical therapist normally evaluates the patient approximately 6 weeks after surgery. In most cases, the patient has been in a cast for those 6 weeks and has had partial weight-bearing status between 2 and 4 weeks. Studies have reported that clinical outcomes may be improved in patients with trimalleolar fractures who have full weight-bearing status in an ankle orthosis between 2 to 4 weeks after surgery.23 A recent systematic review article evaluated nine randomized control studies that compared early motion of the ankle with 6 weeks of cast immobilization and found that early mobility is associated with quicker return to work and improved ankle range of motion after 12 weeks. However, other article’s authors found that early motion was associated with increased risk of wound infection.23,24 Some authors also suggest early active range of motion (AROM) for plantar flexion and dorsiflexion as soon as the surgical incision has healed.24,25 For those patients who are having issues with wound healing, a number of new technologies have been developed to try to accelerate wound healing, such as hyperbaric oxygen therapy, low level laser therapy, nano/microcurrent technology, and infrared light.22,26–28

Evaluation

The initial evaluation establishes the baseline deficits from which further goals and treatment are formulated (Box 29-1). AROM and passive range of motion (PROM) are assessed within the patient’s tolerance. ROM is a primary limitation noted at the initial evaluation. Joint effusion and soft tissue edema are evaluated as well using either a “figure 8” technique, with a standard measuring tape, or by applying volumetrics. The patient’s ambulation is assessed to determine abnormal movement patterns secondary to an antalgic gait. At this stage the patient may have acute pain and be in a fracture boot or other type of orthosis. Often, the patient may experience hardware-related pain, which may have an affect on functional outcomes.29 The physical therapist inspects and evaluates scar mobility. Joint and soft tissue mobility is assessed with an emphasis on the way restrictions limit ROM and function. After enough mineralization and calcium formation have occurred according to the physician, an assessment of the arthrokinematic movements of the ankle joint can be done. For example, posterior glide of the talus is often markedly restricted and has been correlated to restrictions in dorsiflexion and normal gait. In addition, posterior and anterior glide of the proximal and distal fibular heads have been shown to increase AROM and PROM.

After evaluation and discussion, the physical therapist and patient formulate a treatment plan and goals. Belcher et al30 reported impaired function as long as 24 months after an ORIF surgery for a trimalleolar fracture.

Phase I

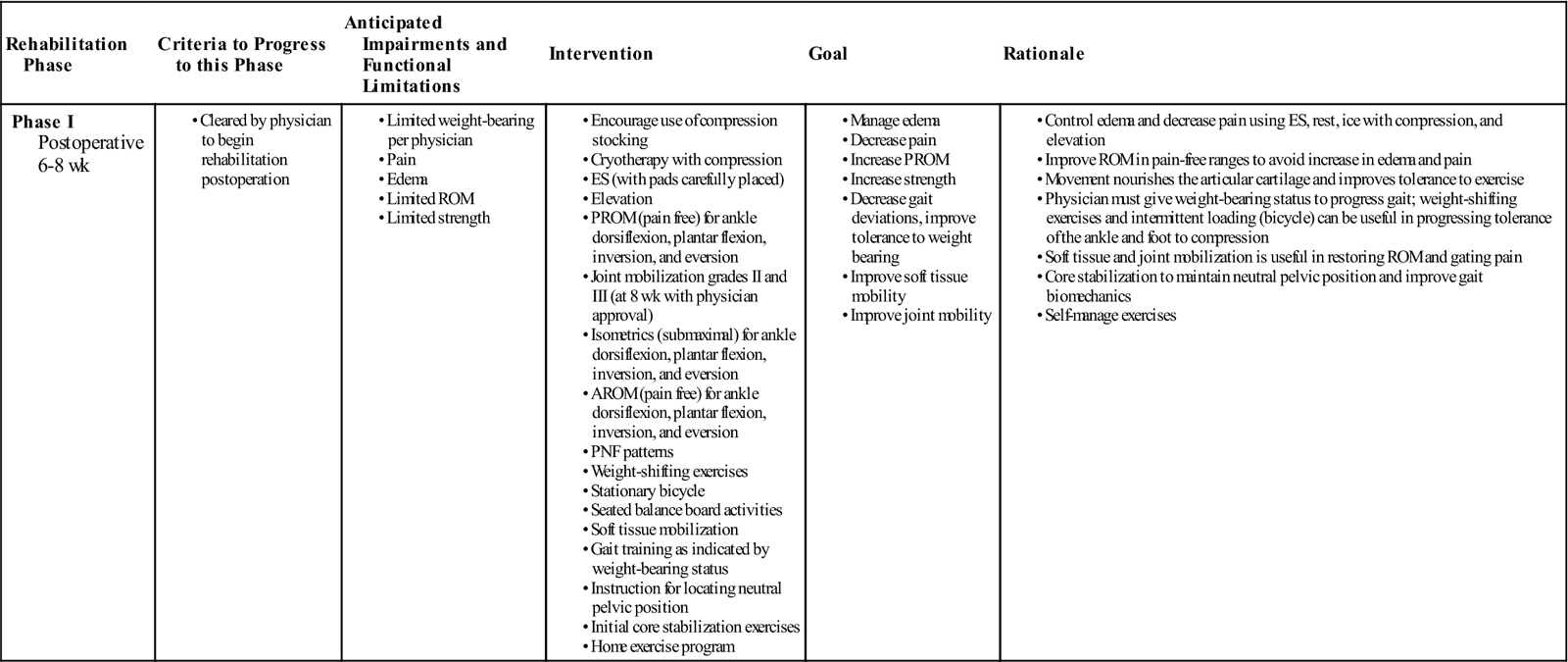

TIME: Weeks 6 to 8 after surgery

GOALS: Minimize pain and swelling, normalize ROM, initiate AROM and therapeutic exercises, normalize gait, increase joint and soft tissue mobility, maintain cardiovascular fitness, and provide patient education (Table 29-1). Treatment goals initially are to decrease pain and swelling, increase ROM and strength, and normalize gait. AROM and PROM are initiated immediately for all planes of movement under the supervision of the physical therapist. AROM can progress from movement with lessened gravity (e.g., in a pool) to movement using gravity as resistance. Soft tissue mobilization of restricted structures is particularly useful in decreasing pain and increasing ROM. Around 8 weeks, with physician approval, joint mobilization of the ankle is implemented using distraction and glide maneuvers.31

TABLE 29-1

Ankle Open Reduction and Internal Fixation

< ?comst?>

| Rehabilitation Phase | Criteria to Progress to this Phase | Anticipated Impairments and Functional Limitations | Intervention | Goal | Rationale |

| Phase I Postoperative 6-8 wk |

|

|

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

![]() Ankle joint mobilizations into resistance are deferred until enough mineralization and calcium formation have occurred (usually 8 weeks). The rehabilitation program also includes gait training and lower extremity strengthening in shallow and deep water in addition to land therapy. Recently, some harness treadmill systems have been developed that can unload the patient’s body weight and decrease his or her fear of falling, allowing the patient to focus more on his or her gait mechanics. Ankle AROM exercises also are initiated in the pool.

Ankle joint mobilizations into resistance are deferred until enough mineralization and calcium formation have occurred (usually 8 weeks). The rehabilitation program also includes gait training and lower extremity strengthening in shallow and deep water in addition to land therapy. Recently, some harness treadmill systems have been developed that can unload the patient’s body weight and decrease his or her fear of falling, allowing the patient to focus more on his or her gait mechanics. Ankle AROM exercises also are initiated in the pool.

![]() The patient should avoid jumping and running exercises in shallow water at this time. However, if lack of ROM and gait are significant problems at the time of the patient’s initial physical therapy evaluation, the therapist may decide to begin land therapy in combination with pool therapy to address specific problems and monitor the patient more closely.

The patient should avoid jumping and running exercises in shallow water at this time. However, if lack of ROM and gait are significant problems at the time of the patient’s initial physical therapy evaluation, the therapist may decide to begin land therapy in combination with pool therapy to address specific problems and monitor the patient more closely.

A compressive stocking is useful to help control soft tissue edema and joint effusion, especially during initial weight-bearing activities. The patient is instructed in a home exercise program incorporating ice, elevation, compression, and light active exercises, such as stationary bicycling or AROM exercises, to reduce soft edema and joint effusion. Pain and swelling are managed with appropriate modalities, such as pulsed ultrasound or electrical stimulation. However, these modalities should not be performed over the metal implants. Just as with quadriceps stimulation following knee surgery, high voltage electrical stimulation may be beneficial in the early phase of recovery to retard any further muscle atrophy of the gastroc/soleus complex that may have resulted secondary to immobilization or weight-bearing restriction.32

Phase II

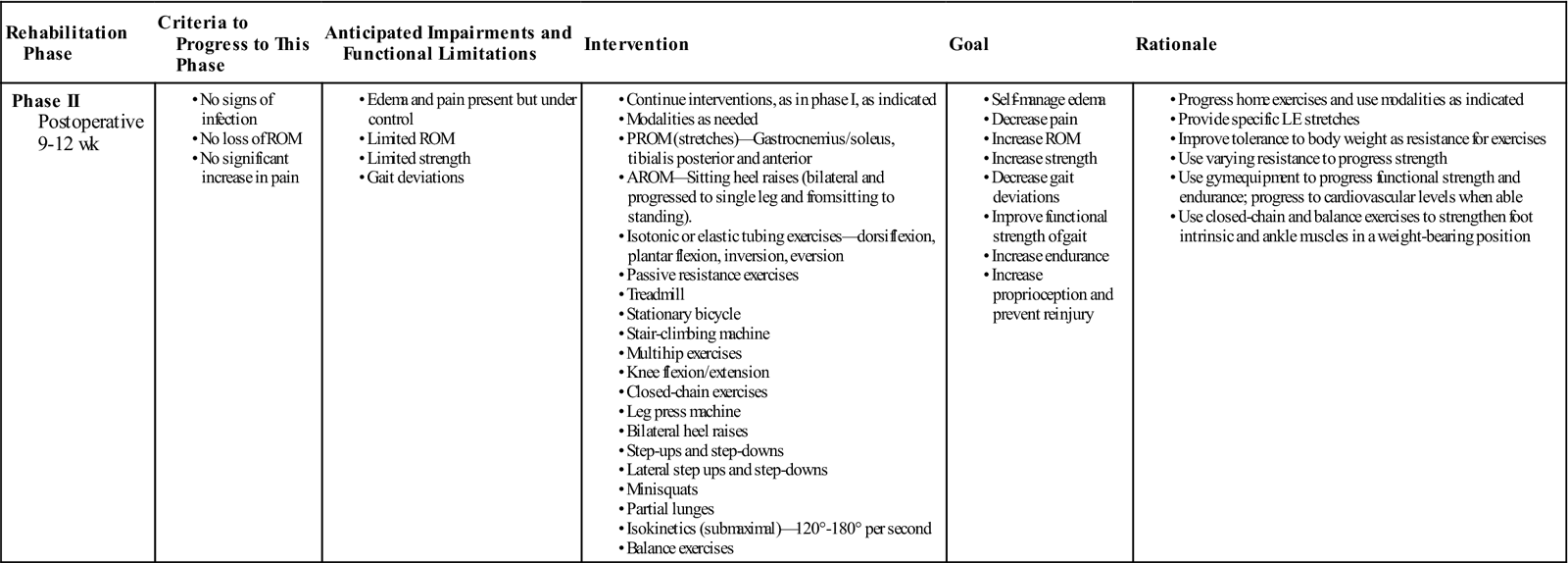

TIME: Weeks 9 to 12 after surgery

GOALS: Minimize pain and swelling, normalize ROM, normalize gait, decrease soft tissue restrictions, increase strength of intrinsic and extrinsic foot and ankle muscles (Table 29-2)

TABLE 29-2

Ankle Open Reduction and Internal Fixation

< ?comst?>

| Rehabilitation Phase | Criteria to Progress to This Phase | Anticipated Impairments and Functional Limitations | Intervention | Goal | Rationale |

| Phase II Postoperative 9-12 wk |

|

|

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

The second phase is initiated after pain and swelling have subsided, usually 9 to 12 weeks after surgery. The second phase of treatment blends with the first as ROM and gait progress to normal. Progressive resistive exercises are used to strengthen the anterior and posterior tibialis, peroneals, and gastrocnemius and soleus muscle groups. A home program, using elastic tubing for resistance, is helpful to augment supervised physical therapy in the office. Treatment options for strengthening exercises include the stationary bicycle, stair-climbing machine, step-ups, step-downs, calf raises, and isokinetic exercises. Specific muscle strengthening for the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles is important to examine because of the likelihood of muscle atrophy. A total lower extremity strengthening program is indicated, as well as a program to maintain cardiovascular fitness. Joint and soft tissue mobilization is continued as indicated. Submaximal isokinetics can be implemented using high speeds such as 120° to 180° per second. The higher velocities prevent excessive resistance that could exacerbate the patient’s symptoms. Proprioceptive activities are increased as the patient begins to demonstrate increased balance; use of a balance board is helpful in developing proprioception. The patient progresses heel raises from sitting to standing to single-leg standing. Modalities such as compression wraps and ice packs are used as indicated for postexercise pain and swelling. Electrical stimulation may be used if the pads are appropriately placed away from plates and pins. The intensity of the rehabilitation should be altered if pain or swelling limit the rehabilitation progression. ![]() Weight-bearing exercises and resisted exercises done too aggressively will exacerbate the symptoms and could delay the rehabilitation process for several weeks.

Weight-bearing exercises and resisted exercises done too aggressively will exacerbate the symptoms and could delay the rehabilitation process for several weeks.

Phase III

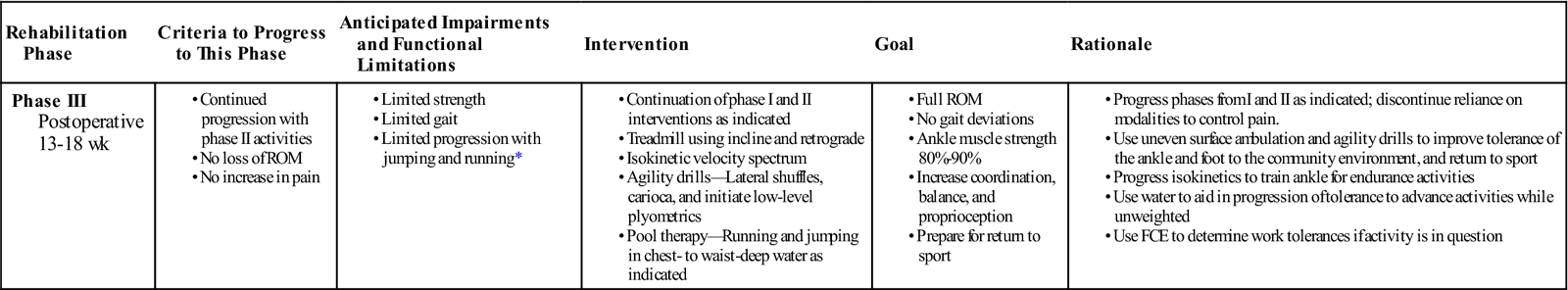

TIME: Weeks 13 to 18

GOALS: Maintain normal limits of ROM, joint and soft tissue mobility, gait, and muscle strength; increase coordination for higher level activities; improve balance and proprioception (Table 29-3)

TABLE 29-3

Ankle Open Reduction and Internal Fixation

< ?comst?>

| Rehabilitation Phase | Criteria to Progress to This Phase | Anticipated Impairments and Functional Limitations | Intervention | Goal | Rationale |

| Phase III Postoperative 13-18 wk |

|

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

FCE, Functional capacity evaluation; ROM, range of motion.

< ?comst1?>< ?comen1?>*< ?comst1?>< ?comen1?>The patient should begin on progressive run and jump training programs during this phase. However, care needs to be taken to ensure that the patient does not experience exacerbations. Adequate rest and recovery time between bouts of activities is essential. If a patient experiences a problem (e.g., increased pain or swelling), the therapist should treat it as an acute injury and should reduce the symptoms before progressing to the next phase.

The third phase of rehabilitation begins approximately 13 to 18 weeks from the time of surgery. The fracture is usually healed by this phase of rehabilitation.25 The patient has progressed to normal ROM and demonstrates a normal gait and increased strength with manual muscle testing. Before progressing to a more aggressive program the patient should be cleared by the surgeon. Therapeutic exercises should progress to include strengthening exercises that are 60% to 70% of maximal effort. This submaximal effort is best determined by the patient’s ability to lift a specific amount of weight 10 times. The ninth and tenth repetitions should be difficult for the patient. Isokinetic strengthening programs can be initiated. The use of various speeds during the workout session is referred to as velocity spectrum. We have found velocity spectrum training useful in promoting strength and power of the extrinsic muscles of the foot and ankle.

Functional training should be initiated for the patient wishing to return to sporting activities or vigorous work. Treadmill walking on an incline or retrograde can be an excellent method of training for the endurance athlete. Pool activities can be used initially for running and jumping.

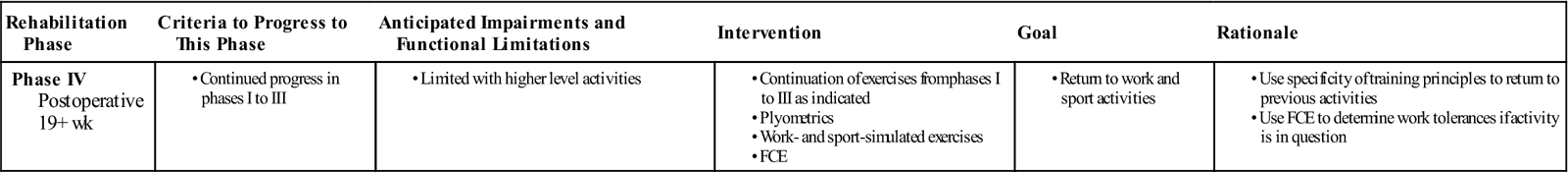

Phase IV

TIME: Week 19 and beyond

GOALS: Return to sporting activities or daily activities without restrictions (Table 29-4)

TABLE 29-4

Ankle Open Reduction and Internal Fixation

< ?comst?>

| Rehabilitation Phase | Criteria to Progress to This Phase | Anticipated Impairments and Functional Limitations | Intervention | Goal | Rationale |

| Phase IV Postoperative 19+ wk |

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

Phase IV is the last phase, starting at 19 weeks after surgery. This phase is used to condition the patient for a return to sports, work, or any activity requiring vigorous movement. Sport-specific activities are carefully implemented with the use of an ankle brace.

Plyometric exercises simulate many sporting activities because of the prestretch to the muscle before contraction. Some examples of plyometric exercises include depth jumping, trampoline, hopping, and jumping over obstacles. However, plyometric exercises are stressful to joints and soft tissue structures and should be initiated after normal muscle strength is obtained throughout the lower limb.

Precautions

A trimalleolar fracture is a serious injury. Secondary problems and complications can occur during postoperative rehabilitation. Occasionally low back or sacroiliac pain develops as a result of the antalgic gait with the cast or fracture boot. This is treated symptomatically with emphasis on the need to normalize gait as soon as possible or restrict ambulation activities.

Overuse injuries such as plantar fasciitis secondary to a preexisting overpronation may be treated with modalities and foot orthosis. Because limited dorsiflexion is sometimes an issue, a low-load prolonged stretch for dorsiflexion over 2 to 30 minutes is effective. This can be done in conjunction with moist heat or ultrasound to the gastrocnemius and soleus muscle group.

Suggested Home Maintenance for the Postsurgical Patient

An exercise program has been outlined at the various phases. The home maintenance box outlines rehabilitation suggestions the patient may follow. The physical therapist can use it in customizing a patient-specific program.

Troubleshooting

Residual problems after surgical anatomic restoration of the ankle joint include chronic pain, loss of motion, recurrent swelling, and perceived instability. The cause of such poor outcomes is often unclear, but it may be related to missed occult intraarticular injury.10,33–35 Other postoperative problems that can develop include malunion or nonunion, loosening or fracture of the internal fixation devices, infection, and wound problems. These complications are rare. Unless contraindicated, the physical therapist must work on mobilization of the scar or scars, as well as general stretching and mobilization of the joint. Care should be taken to increase soft tissue and ankle flexibility gradually and not to stretch or stress the joint excessively to gain more rapid and improved ROM. Pool therapy should be used initially, with some land therapy; as the patient progresses, land therapy increases and pool therapy diminishes. The physical therapist also must take care to avoid pushing the ankle too hard, resulting in increased swelling, pain, and subsequent loss of motion.

The physician should be notified immediately if the patient develops significantly increased pain, swelling, loss of motion, or wound healing problems. In addition, if signs of infection or loosening of the internal fixation develop, the physician should be notified immediately.

Summary

In the next century, continued advances in surgical techniques and rehabilitation will allow patients to return earlier to their work and sports activities. As additional physicians and physical therapists specialize in foot and ankle problems, more basic and clinical research will be carried out to “push the envelope” of progress to improve foot and ankle care.

Clinical Case Review

1Amy is a 30-year-old female who suffered a bimalleolar fracture while playing soccer. She underwent an ORIF procedure on her ankle 15 weeks ago. Amy complains of tightness, which progressively increases throughout the day as she performs her functional daily activities. How did the therapist address this issue in her treatment plan?

When a patient complains of stiffness, it is always necessary to determine if the problem is joint or soft tissue in nature. The therapist assessed the patient and found significant restrictions with proximal fibular anteroposterior (AP) glides and distal fibular posteroanterior (PA) glides. These were treated appropriately, and the patient immediately noticed a decrease in her “stiffness.”

2Lauren is a 23-year-old female who suffered a bimalleolar fracture secondary to a motor vehicle accident. Lauren has progressed well; however, she has noticed increased purulent discharge from her incision at an area that is having difficulty closing. Upon assessment, increased skin temperature and redness around the incision was also noted. What was done?

The physician was notified, and the patient was sent for a follow-up visit. Tests showed the patient had developed an infection at the incision site, and she was placed on a broad-spectrum antibiotic. Whirlpool treatment was initiated, maintaining the water at 98° F to 100° F for 20 minutes, three times per week. General wound care was provided, and her rehabilitation schedule continued in a modified fashion.

3Brittany is a 30-year-old female who suffered a bimalleolar fracture and had ORIF 16 weeks ago. Brittany has returned to her position as an art teacher, which requires her to stand frequently throughout the day. Since returning, Brittany reports she has had increased lateral ankle pain, which is greater in the afternoon and evening. How did the therapist treat this patient?

Brittany was assessed and it was found that her AROM and strength were within normal limits. She had the option of having the hardware removed once healing occurred; however, Brittany refused to have additional surgery. Brittany was issued a home TENS unit and was instructed in its use, as well as precautions and contraindications. She was also issued an ankle-stabilizing orthosis (ASO) brace to wear during work and with activities requiring prolonged walking and running. Finally, the therapist discussed various options for allowing changes in the length of time she stands during the day (the therapist recommended she use a stool while lecturing).

4Sarah is a 23-year-old college senior who suffered a right ankle bimalleolar fracture and had ORIF 6 weeks ago. On arriving to the clinic for a treatment session, she complained of experiencing increased right calf pain exacerbated with weight bearing. Sarah also reported that she noticed her right calf felt “hot” to touch as compared with the left. She has not slept well the last two nights secondary to the previously mentioned symptoms. How did the therapist proceed?

Further assessment by the therapist revealed a positive Homans sign at the right calf. The physician was notified, and the patient was sent immediately to the hospital for an ultrasound, which showed the patient had developed a deep vein thrombosis (DVT). The patient was admitted to the hospital where anticoagulant therapy was initiated.

5Braeden is a 19-year-old male who suffered a bimalleolar fracture 20 weeks ago with corresponding ORIF. He received physical therapy at another facility after his surgery for 10 weeks. Braeden has been referred to the therapist’s facility with a chief complaint of pain inferior to the lateral malleolus and at the Achilles tendon insertion. Pain is minimal in the morning and progressively worsens throughout the day. The patient was noted to have decreased calcaneal abduction and demonstrated increased pronation on the affected side. The patient was also noted to have 5° of dorsiflexion. How did the therapist proceed?

Grades III and IV joint mobilization was performed for AP talar glides and grades III and IV physiologic calcaneal abduction. A contract-relax technique was initiated to increase dorsiflexion. The patient was then taught how to perform the contract-relax technique as a home exercise. Exercises to increase strength in the peroneals and the gastrocnemius and soleus complex were also performed. Additionally, a 3° wedge was inserted into the right shoe medially to decrease the angle of pronation. The patient was later casted for custom orthotics.

6Eric is a 26-year-old football player who injured his ankle when his foot got caught under another player. His injury resulted in a compound fracture to both his right tibia and fibula. His injury was treated with ORIF, and he is presenting to the therapist for his initial evaluation 8 weeks following the surgery. He was non–weight-bearing for the entire period before beginning therapy. How should the therapist begin treatment of Eric at this time?

The initial assessment should include examination of the ankle’s active and passive range of motion within limits of his pain tolerance. The therapist should inspect the surgical sites for signs of possible infection. Strength testing should be deferred at this stage. Treatment may begin with modalities to promote healing and reduce excessive scar tissue formation, such as infrared light, ultrasound, and scar massage if warranted. If visible atrophy of the gastroc/soleus complex is noted, the therapist can take circumferential or volumetric measurements and initiate high-voltage electrical stimulation. The patient should be given a home program, including active and active assistive range of motion exercises, for plantar flexion, dorsiflexion, inversion, and eversion, which should not induce pain. Eric then should be educated on how to progress with his gait training. For example, he should start with bilateral axillary crutches and WBAT. Once he has proper mechanics and is able to ambulate without pain he can be weaned to one axillary crutch on the contralateral side, then to a single point cane, and finally no assistive device.

7Lorraine is 30-year-old female who injured her ankle in a rollover all terrain vehicle (ATV) accident. She was found to have fractured her left distal tibia, along with a Lis Franc fracture in her left foot. Both injuries were addressed with ORIF. After undergoing rehabilitation for the first 4 months, she has now begun to return to work at a retail sales position. She reports increased lateral foot pain, lateral swelling, and pain along the distal medial tibia extending into her arch. How would the therapist address her complaints?

Upon evaluation of Lorraine’s gait mechanics, a collapse of the midtarsal joints was found during the stance phase of gait. To address this and her medial distal tibia tenderness, custom orthotics were fabricated to help support the midtarsal area during ambulation. Lorraine also was noted to have restricted dorsiflexion of the talocrural joint, restricted cuboid mobility, and limited first metatarsophalangeal joint mobility. The following manual therapy techniques were used to improve her joint mobility: talocrural distraction; anterior and posterior glides of the talus; anterior/posterior glides of the cuboid; and traction with anterior/posterior glides of the first metatarsophalangeal joint. Lorraine was educated on trying to take more frequent breaks while working, so that her ankle does not become as swollen following her work activities.

8Kate is a 21-year-old who fractured both of her ankles in a fall. She required both external fixation and ORIF procedures to restore proper alignment and to allow for proper bone healing. Kate was non–weight-bearing for 4 months after the injury. She now presents to PT approximately 1 year after the injury. She has recently began to return to running and is complaining of bilateral Achilles tendinitis. What type of exercise program should Kate be placed on to address her problem?

Eccentric exercise programs have been shown to have beneficial results in tendon strengthening. However, initially the patient must be started at an exercise intensity that does not exacerbate the tissue while it is still inflamed. The initial treatments may consist of modalities to reduce pain, swelling, or tenderness in the area and begin a gentle gastroc/soleus towel stretching program. The exercise progression may begin starting with double leg calf raises, three sets of 15 repetitions, adding one to two sets every week of treatment, depending on the patient’s response to the exercise program. After 4 to 6 weeks of double leg calf raises, the patient may progress to single leg calf raises and start the program over along the same progression as before. Kate will start the exercise by standing on the edge of a step and raising up on her toes as high as she can. After pausing at the apex, she should then start slowly lowering herself back to the ground, if possible, at a 5- to 7-second descent is ideal.

9Sally is a 45-year-old female who fractured her left ankle when she fell off of her horse. She was treated with ORIF in the days following the injury and has progressed through rehabilitation after initially being non–weight-bearing for 8 weeks. She is now approximately 4 months out from surgery and is ambulating without any assistive device. Sally has been complaining of left medial knee pain and swelling with prolonged weight-bearing activities. Upon further evaluation the therapist is concerned of possible cartilage/meniscal pathology, how should the therapist proceed?

After a severe traumatic injury, such as an ankle fracture that requires ORIF, the immediate concern is to stabilize the injury and prevent any secondary injury; for example, compartment syndrome or infection. Sometimes in these types of injuries, other pathology further up the kinetic chain may not be recognized until later in the treatment process once the patient begins to perform more aggressive weight-bearing activities. The patient should be referred back to her orthopedist, and the therapist should contact the orthopedist and relay his or her concerns and objective findings. In Sally’s case, she had medial joint line tenderness, occasional crepitus, and pain with stair climbing, as well as positive Apley compression and Thessaly meniscal special tests. The patient underwent imaging after seeing the orthopedist and was found to have a medial meniscus tear, which was addressed with arthroscopy.

10Allan is a 25-year-old basketball player who fractured his right ankle while landing on an opponents foot during a game. His fracture was stabilized with ORIF, and he was placed in a controlled ankle movement (CAM) boot approximately 4 weeks after the procedure. He has been progressing with his rehabilitation and is now 6 months after his surgery. He has recently begun sport-specific activities, such as running, jumping, and cutting. Describe a proper exercise progression for Allan at this stage of his rehabilitation.

Before beginning higher impact activities, including running, jumping, and cutting required for sports like basketball, the patient must demonstrate necessary lower extremity strength and sufficient soft tissue and joint mobility before attempting more vigorous activities. Also, the patient should have been placed on a neuromuscular and perturbation training program with an emphasis on landing mechanics and proprioception before beginning the more advanced weight-bearing activities. To begin, Allan may begin jumping either in a pool or on devices (i.e., Shuttle MVP) that allow for partial weight-bearing—first beginning with bilateral lower extremity exercises and then progressing to unilateral. Once he has progressed through this phase, Allan may begin more full weight-bearing exercises, such as jump squats, single leg hops over obstacles, and multidirectional lunges. The last phase should incorporate sport-specific agility drills while maintaining focus on proper mechanics and joint protection. For example, Allan may perform a shuttle drill with a different basketball skill or maneuver required at each station of the drill.

11Angela is a 55-year-old female who experienced an open fracture of her left ankle when she fell off of a step. She underwent surgical repair of the injury, but had issues with wound closure following the procedure and required a skin graft. Angela is a diabetic and has issues with circulation to her distal extremities secondary to her diabetes. She presents to physical therapy 8 weeks after the injury. Her wound has still not fully healed but does not demonstrate signs of infection (i.e., warmth, redness, tenderness, or drainage surrounding the wound). What should the therapist do to assist with wound healing at this stage in her recovery.

The therapist should contact the referring doctor to relay concerns regarding the patient’s slow wound healing. Recently, newer technologies have been developed to assist those who may have issues with wound healing. Treatment options that may be considered by the surgeon and therapist include hyperbaric oxygen treatments, infrared light therapy, microcurrent/nanocurrent electrical stimulation devices, and traditional wound care (using a variety of topical creams and/or dressings). Angela should be educated on not trying to stress the healing area excessively while the tissue is still fragile; for example, being on her feet for a number of hours continuously leading to increased swelling, which may further delay healing. Also, the patient needs to be educated on reducing other lifestyle factors, which might impede healing, such as smoking or illicit drug use, nutritional status, proper rest and recovery, or any medications that may delay healing. Wound healing needs to be obtained first before the patient may progress to the next phase of the rehabilitation process.