Open Inguinal Hernia Repair

Terminology

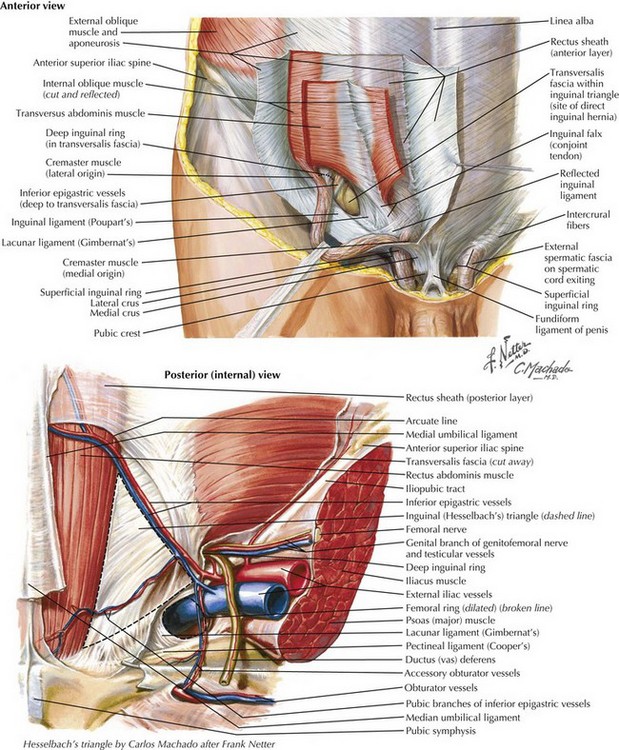

In referring to inguinal hernias, a major defining point is location of the defect—direct versus indirect. This distinction is strictly anatomic because the operative repair is the same for both types. Approximately two thirds of inguinal hernias are indirect. Men are 25 times more likely to have an inguinal hernia than women, and indirect hernias are more common regardless of gender. A direct inguinal hernia is defined as a weakness in the transversalis fascia within the area bordered by the inguinal ligament inferiorly, the lateral border of the rectus sheath medially, and the epigastric vessels laterally (Fig. 28-1). This area is referred to as Hesselbach’s triangle.

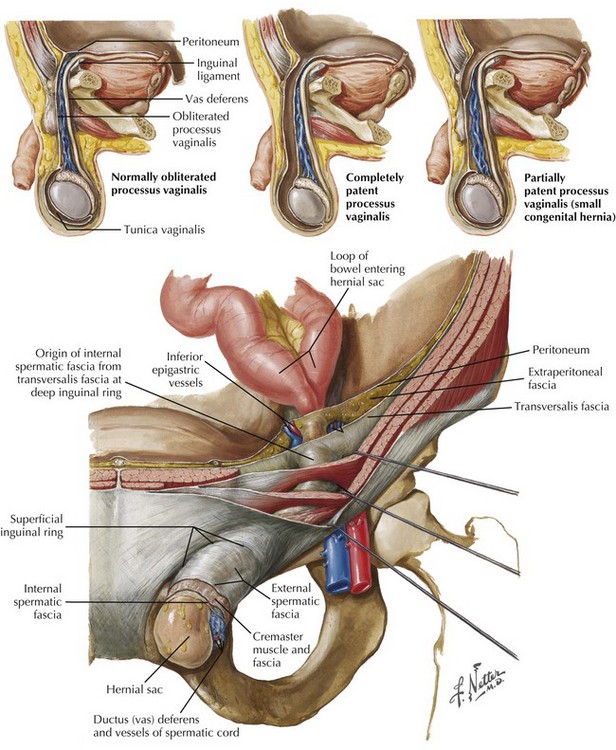

Located lateral to the inferior epigastric vessels, an indirect inguinal hernia is characterized by the protrusion of the hernia sac through the internal inguinal ring toward the external inguinal ring and, at times, into the scrotum. Indirect inguinal hernias result from a failure of the processus vaginalis to close completely (Fig. 28-2). An inguinal hernia that has direct and indirect components is referred to as a pantaloon hernia.

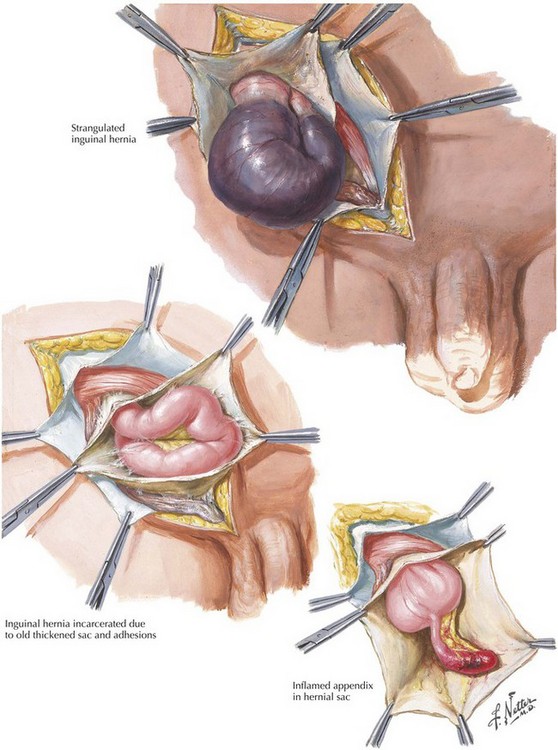

A hernia is defined as reducible if its contents can be placed back into the peritoneal cavity, alleviating their displacement through the musculature. In contrast, a hernia with contents that cannot be reduced is termed incarcerated (Fig. 28-3). If the blood supply to the contents of the hernia is compromised, the hernia is defined as strangulated. Strangulation is a potentially fatal complication of a hernia and should always be considered a surgical emergency. Less common inguinal hernias include Amyand’s hernia, with the appendix (normal or acutely inflamed) contained in the hernia sac, and Littre’s hernia, which contains a Meckel’s diverticulum.

Surgical Approach

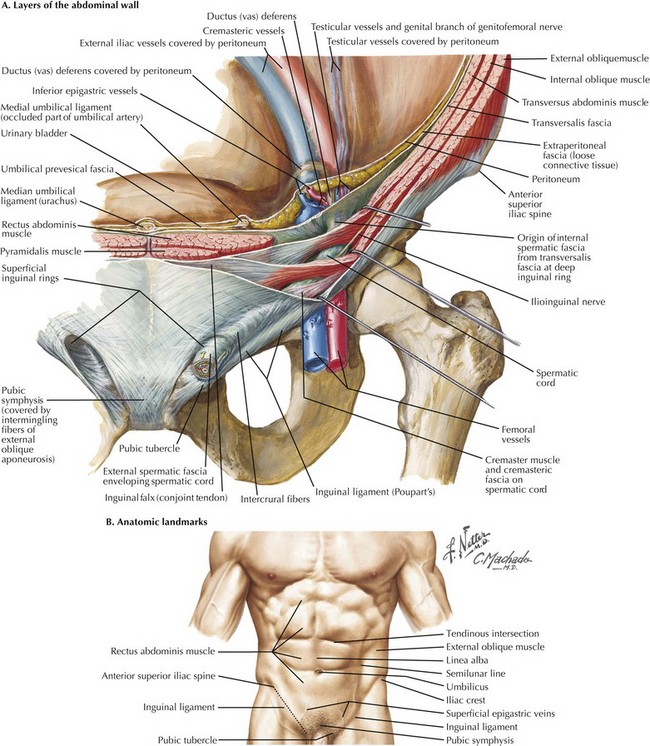

To understand the anterior approach, the surgeon must appreciate the layers of the abdominal wall and their relation to the inguinal canal. The layers and the location of their neurovascular structures include skin, subcutaneous fat (e.g., Camper’s and Scarpa’s fasciae), muscles (external and internal oblique, transversus abdominis), transversalis fascia, preperitoneal fat, and peritoneum (Fig. 28-4, A).

The inguinal canal is approximately 4 cm in length and extends from the internal inguinal ring to the external inguinal ring. Within the inguinal canal lies the spermatic cord, which consists of the testicular artery, pampiniform venous plexus, the genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve, the vas deferens, cremasteric muscle fibers, cremasteric vessels, and the lymphatics. The superficial border of the inguinal canal is the external oblique aponeurosis. As the external oblique aponeurosis forms the inguinal (Poupart’s) ligament, it rolls posteriorly, forming a “shelving edge,” and defines the inferior border of the inguinal canal with the lacunar ligament. Posteriorly, the inguinal canal is bound by the transversalis fascia, often referred to as the “floor” of the inguinal canal. The inguinal canal is bound superiorly by the internal oblique and transversus abdominis musculoaponeurosis (see Fig. 28-1).

Before making an incision, it is essential for the surgeon to identify the landmarks defining the inguinal ligament. The anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) and pubic tubercle are the insertion points for the inguinal ligament (Fig. 28-4, B). One of the challenging aspects of open inguinal hernia repair is securing the mesh to medial components. To help expose this area, the incision should begin over the pubis and extend 1 to 2 cm cephalad to the inguinal ligament, from the external ring to the internal ring.

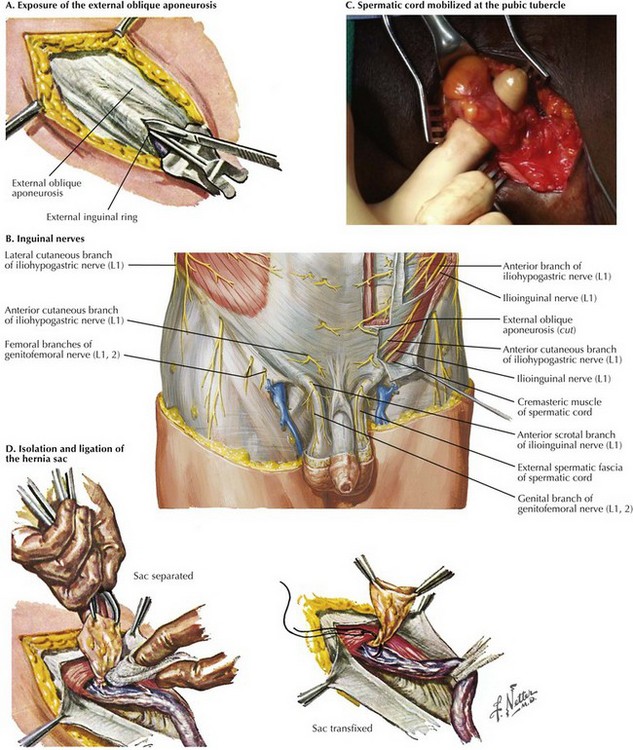

Dissection through the subcutaneous fat and Scarpa’s fascia leads to the external oblique aponeurosis. Once encountered, the external oblique aponeurosis is completely exposed and the external inguinal ring is identified. The external oblique aponeurosis is incised sharply. The incision is extended along the fibers of the external oblique aponeurosis to the external inguinal ring, to expose the inguinal canal (Fig. 28-5, A).

At this time it is important to identify and isolate the iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves to avoid injury. Failure to identify these nerves puts patients at greater risk of developing chronic pain through entrapment or transection. The iliohypogastric nerve is typically found lying on the internal oblique abdominal muscle after the edges of the external oblique aponeurosis are elevated. The ilioinguinal nerve runs along the spermatic cord through the internal inguinal ring and terminates at the skin of the upper and medial parts of the thigh (Fig. 28-5, B). Studies suggest a similar incidence of chronic pain whether the nerves are intentionally transected or preserved. Regardless of approach, identification of the nerves is critical to prevent inadvertent entrapment.

Through a combination of sharp and blunt dissection, the spermatic cord is mobilized at the pubic tubercle (Fig. 28-5, C). Staying close to the pubic tubercle avoids confusion of the tissue planes and disruption of the floor of the inguinal canal. Once mobilized, the spermatic cord is encircled with a Penrose drain to allow for easy retraction. Avoiding excessive traction is important to reduce testicular engorgement and early postoperative discomfort.

To facilitate identification of the hernia sac, the cremaster muscle is separated from the spermatic cord through blunt dissection. The hernia sac is usually found anterior and superior to the spermatic cord in an indirect hernia, whereas the sac protrudes directly through the floor of the inguinal canal in a direct hernia. During repair of an indirect hernia, the sac is cautiously separated from the spermatic cord down to the level of the internal inguinal ring. The hernia sac is examined for visceral contents. With a large hernia, the sac may be opened to ensure there are no contents before ligation and reduction. The hernia sac can be reduced into the preperitoneal space, or the neck of the sac is ligated at the internal inguinal ring and excess sac excised (Fig. 28-5, D). If present, a lipoma of the cord, with retroperitoneal fat herniating through the internal inguinal ring, should be ligated and excised before the surgeon begins repair of the inguinal canal.

Tension-Free Repair

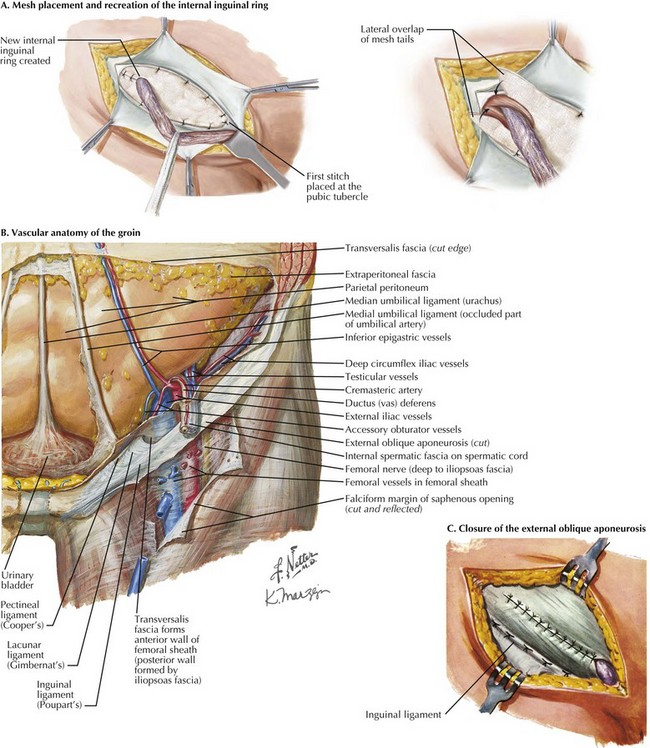

Guided by the principle that tension increases recurrence in hernia repair, placement of synthetic mesh to reinforce the floor of the inguinal canal and recreate the internal inguinal ring has become the primary method of anterior inguinal hernia repair. Using a nonabsorbable synthetic mesh, a slit is cut in the distal lateral edge to accommodate the spermatic cord. The mesh is first secured to the pubic tubercle with a nonabsorbable monofilament running suture (Fig. 28-6, A).

Three or four interrupted sutures are placed along the conjoined tendon or transversus abdominis muscle to the internal inguinal ring. Inferolaterally, the suture is run along the shelving edge of the inguinal ligament to a point lateral to the internal inguinal ring. The tails of the mesh are sutured together, creating a new internal inguinal ring through which the spermatic cord structures and ilioinguinal nerve are placed (Fig. 28-6, A).

It is of critical importance when fixing the mesh in place at the inguinal ligament to respect the femoral vessels, which run directly below the inguinal ligament in the femoral sheath (Fig. 28-6. B).

After the mesh is secured, the external oblique aponeurosis is reapproximated with braided absorbable suture from lateral to medial. During closure of the external oblique aponeurosis, the external inguinal ring is recreated. Scarpa’s fascia is reapproximated, and a continuous subcuticular stitch is used for skin closure (Fig. 28-6, C).

Primary Tissue Repair

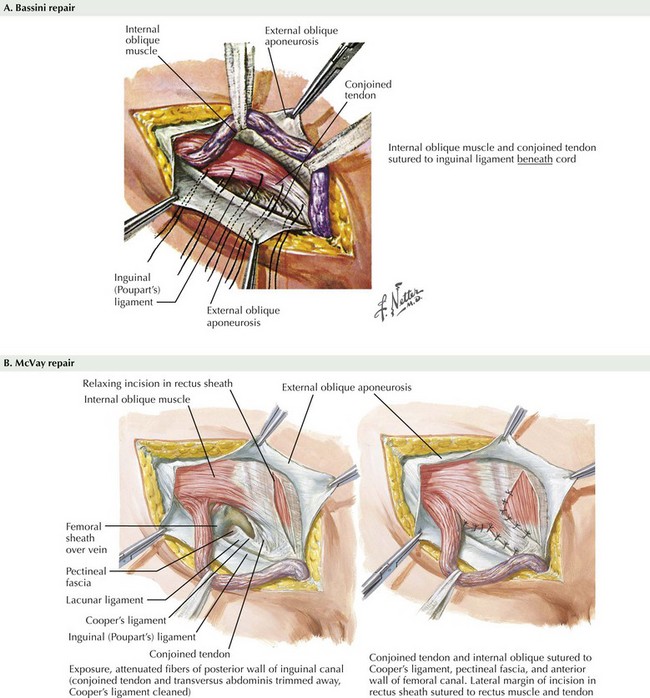

Knowledge of primary tissue repair techniques will aid any surgeon who encounters an inguinal hernia in the setting of contamination, where mesh placement is contraindicated. Methods of primary tissue repair include the Bassini, McVay, and Shouldice repairs. The Bassini repair is performed by suturing the conjoined tendon (inguinal falx)—the distal ends of the transversus abdominis and internal oblique muscles—to the inguinal ligament (Fig. 28-7, A).

An alternative to suturing the musculoaponeurotic structures to the inguinal ligament is to suture them to Cooper’s ligament. The McVay repair, or Cooper’s ligament repair, uses a relaxing incision through the anterior rectus sheath to limit the tension on the suture line. To initiate this repair, interrupted nonabsorbable suture is used to approximate the transversus abdominis muscle to Cooper’s ligament. This is continued down the pubic spine to the end of the ligament. A transition stitch is placed to approximate Cooper’s ligament and the iliopubic tract. The McVay repair is completed by approximating the edge of transversus abdominis muscle to the iliopubic tract (Fig. 28-7, B).

Fitzgibbons, RJ, Jr., Giobbie-Hurder, A, Gibbs, JO, et al. Watchful waiting vs repair of inguinal hernia in minimally symptomatic men: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2006;295:285–292.

Neumayer, L, Giobbie-Hurder, A, Jonasson, O, et al. Open mesh versus laparoscopic mesh repair of inguinal hernia. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1819–1827.

Sarosi, GA, Wei, Y, Gibbs, JO, et al. A clinician’s guide to patient selection for watchful waiting management of inguinal hernia. Ann Surg. 2011;253:605–610.

Woods, B, Neumayer, L. Open repair of inguinal hernia: an evidence-based review. Surg Clin North Am. 2008;88:139–155.